Abstract

Background

Hailey-Hailey Disease (HHD) is an autosomal dominant skin disorder characterized by erythematous and sometimes vesicular, weeping plaques of intertriginous regions. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising in lesions of HHD have been described in the literature. There are no reports of melanoma or non-cutaneous malignancies in association with HHD.

Observation

We present 2 patients with HHD, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Patient 1 had a mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid. The second patient had a history acute monoblastic leukemia, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and radiologic evidence of an acoustic neurilemmoma. We hypothesize the mechanisms of oncogenicity in these patients, including genetic, environmental, and iatrogenic factors.

Conclusion

The cause of the cancers in these patients is likely multifactorial. There are prior studies to suggest that patients with HHD may have a genetic predisposition to the development of cancer, however, this needs to be verified with additional research in the future.

Keywords: Hailey-Hailey disease, melanoma, carcinogenesis, secondary malignant neoplasms

Introduction

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also termed familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal dominant skin disease first described in 1939 by the Hailey brothers.1 Patients typically have onset of disease between the second and fourth decades and present with blisters, erythema, and malodorous plaques in intertriginous locations.2 Longitudinal white bands of the fingernails may be a helpful diagnostic clue.2 Exacerbating factors include friction, heat, sweating, ultraviolet radiation, and superinfection.2 Family history is often of help in diagnosis; however, up to one third of cases represent sporadic mutations with no family history.3 Histologically, HHD is characterized by extensive epidermal suprabasilar acantholysis, which may have the appearance of a “dilapidated brick wall”. In 2000, Hu and Sudbrak identified the ATP2C1 gene located on chromosome 3q21-q24.4-6 More than 80 mutations in this gene have been reported in HHD.7 The ATP2C1 gene encodes for the human secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase (hSPCA1) protein associated with the Golgi apparatus and is expressed abundantly in keratinocytes.7

Malignant melanoma of the skin is increasingly common, and patients with one melanoma have increased risk of second primary melanomas, but diagnosis of 3 or more distinct primary melanomas is uncommon.8 In the present report, we present 2 patients with HHD, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. To our knowledge, the literature contains no prior reports of melanoma or non-cutaneous malignancies in association with HHD. We hypothesize possible mechanisms of oncogenicity in these patients with HHD.

Patient Presentations

Patient 1

A 67-year-old man presented to the surgical oncology clinic for treatment of multiple primary melanomas. His first diagnosis of melanoma occurred at the age of 46 and was treated with wide excision. More recently, over a 1-year period, he has been diagnosed with 5 additional primary melanomas on his trunk and upper extremities. Three of these were Clark’s level IV with Breslow depths of 3.45 mm, 4.03 mm, and 5.12 mm; he had one Clark’s level III melanoma, with a Breslow depth of 0.91 mm, and a Clark’s level II melanoma, with a Breslow depth of 0.28 mm. The latter specimen also contained a separate dermal nodule of melanoma, which was believed to be a metastasis. Most of his specimens have shown concurrent histologic features of HHD and melanoma as demonstrated in Figure 1. Fine needle aspiration of a left axillary mass revealed metastatic melanoma, which was surgically resected. Other staging was negative at that time, and he has been enrolled in an experimental melanoma vaccine trial.

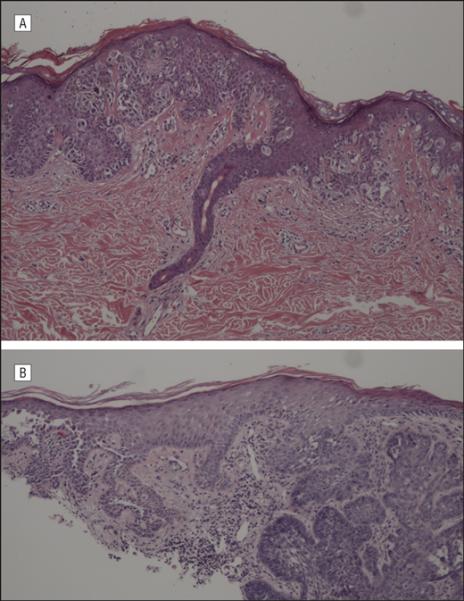

Fig 1.

From the left upper back of Patient 1. A, An asymmetric 5 × 4 cm pink and tan patch with central pink papule. B and C, Biopsy specimens revealing melanoma with epithelioid and spindle cell morphology and extensive epidermal acantholysis giving a “dilapidated brick wall” appearance consistent with Hailey-Hailey Disease. (B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification X100, C, S100 protein stain, original magnification X200.)

This patient has Fitzpatrick type III skin. He reports significant sun exposure during his life, rare sunscreen use during his youth, and approximately 12 blistering sunburns before the age of 20. There was no family history of melanoma. HHD is present in his maternal grandmother, mother, sister, and nephew.

Past medical history was significant for HHD, asthma, osteoarthritis, benign colon polyps, benign prostatic hypertrophy, vertigo, nephrolithiasis, hypertension, and gastroesophageal reflux. Also, at the age of 64, he was diagnosed with high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the left parotid gland with metastasis to the left cervical lymph nodes. This was treated with a combination of left total parotidectomy, left superior cervical lymph node dissection, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and local irradiation with a dose of 66 Gy. His postoperative course was complicated by episodes of gustatory hyperhidrosis.

Patient 2

A 35-year-old man presented to the surgical oncology clinic for treatment of his first melanoma of his right upper back which was at least a modified Clark’s level III and at least 0.83 mm, with the melanoma extending to the base of the biopsy specimen. Sentinel nodes of the right axilla were negative for metastasis. He subsequently noted a papule on the plantar aspect of his left foot. Due to the atypical clinical appearance of this lesion, it was initially treated as a callus and plantar wart. (Fig 2) Ultimately, it was diagnosed as an acral lentiginous melanoma, which was at least Clark’s level IV with a Breslow depth of at least 8 mm. Wide resection was performed, and sentinel lymph node biopsy identified 2 positive nodes in the left groin. In addition, a third melanoma was diagnosed on his right arm with a Clark’s level II and Breslow depth of 0.33 mm. (Fig 3A) Metastatic work-up was negative for distant disease.

Fig 2.

A, Atypical appearing melanoma on plantar surface of left foot of Patient 2. B, ulcerated tumor with dermal infiltrate of pleomorphic spindled melanocytes, confirmed with Melan-A stain. (not shown) (B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification X100.)

Fig 3.

Biopsy specimens from Patient 2 revealing histopathologic features of A, superficial spreading melanoma, predominately in-situ and B, basal cell carcinoma and Hailey-Hailey Disease. (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnifications X100.)

Regarding other skin conditions, he has HHD, numerous dysplastic nevi, and a history of approximately 12 basal cell carcinomas of the arms and back (Fig 3B). He is Fitzpatrick skin type II and reports significant sun exposure with minimal sunscreen use as a youth. He recalls approximately 6 blistering sunburns prior to age of 20.

This patient’s past medical history is notable for several malignancies. At the age of 19, he developed leukemia. Initially, his leukemia was indeterminate morphology; therefore, while awaiting final typing, he was treated with 2 doses of vincristine and 7 days of prednisone. After additional testing, he was diagnosed with acute monoblastic leukemia (AMoL), M5 subtype, which was treated with cytarabine and daunorubicin. Subsequently, he received 1200 cGy total body irradiation, high dose cyclophosphamide and methotrexate in preparation for allogeneic stem cell transplant donated by his HLA-matched sister. After the transplant, he was placed on cyclosporine for approximately 5 months. He has had no recurrence of leukemia nor other hematologic disorder.

At the age of 30, he developed a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the cervical spine, which was resected and treated with 4860 cGy of localized radiation therapy. More recently, a mass of the right cerebellopontine angle has been noted on magnetic resonance imaging; this is suggestive of a vestibular schwannoma.

His mother had numerous atypical nevi and a melanoma. HHD was present in his father and paternal aunt. There was no family history of neural tumors.

Discussion

Both of these patients have a diagnosis of HHD, multiple primary melanomas, and at least 1 other type of cancer. The mechanism underlying carcinogenesis in these patients is likely multifactorial. Contributing factors include skin type and excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation. We discuss the possible genetic and iatrogenic mechanisms of oncogenicity in these 2 patients.

Although there are reports of cutaneous malignancies arising in HHD, there are no reports of melanoma arising in patients with HHD. There are 4 reports of squamous cell carcinoma and 2 reports of basal cell carcinoma arising in lesions of HHD.3, 9-15 Presumably, the impaired epidermal barrier may allow for infection with oncogenic strains of human papilloma virus (HPV), thus promoting the development of squamous cell carcinoma. HPV was detected in 1 case of HHD-associated squamous cell carcinoma.15

Based upon molecular studies done on HHD, there are additional data to suggest that, in theory, HHD patients may be predisposed to neoplasia. Recently, Okunade et al demonstrated that a heterozygous mutation of the ATP2C1 gene in mice leads to an increased incidence of squamous cell tumors in aged adult mice.16 It is suggested that this mutation leads to Golgi stress, increased apoptosis, and a genetic predisposition to cancer.16 Additionally, cancer transformation is commonly associated with rearrangement of calcium channels leading to cellular proliferation and impaired apoptosis.17 Therefore, it is possible that the aberrant calcium signaling in HHD may promote an oncogenic environment. Cialfi et al demonstrated that HHD keratinocytes undergo oxidative stress, which may contribute to DNA damage.18 They also found downregulation of Notch1 and Itch in HHD keratinocytes.18 It has been reported that Notch1 may act as a transforming oncogene in human melanocytes, therefore, in terms of Notch 1 levels, HHD patients should, in theory, be at decreased risk for advanced melanomas.19 Decreased Notch 1 levels may not be a sufficient protective factor, as suggested by the multiple advanced melanomas in the 2 patients in this report.

Alternatively, the chemotherapy and localized radiation that Patient 1 received for his mucoepidermoid carcinoma may have placed him at risk for development of secondary malignant neoplasms (SMN). The same holds true for Patient 2; it is likely that the chemotherapy, total body irradiation (TBI) and immunosuppression after his stem cell transplant made him more susceptible to developing SMNs. For survivors of childhood cancer, the risk of developing a second cancer can be up to 35 times greater than in the general population, occurring at an incidence of 4%.20 Melanoma after childhood cancer has been reported after treatment of primary hematologic malignancies.21 Guerin found a trend towards increased risk of melanoma as a second malignancy after treatment with a combination of alkylating agents and mitotic spindle inhibitors, though these data were not statistically significant.22 Patient 2 was treated with cyclophosphamide, an alkylating agent and 2 doses of vincristine, a mitotic spindle inhibitor. Interestingly, carboplatin and paclitaxel, the chemotherapy agents used to treat Patient 1’s mucoepidermoid carcinoma, have been investigated as a possible treatment for metastatic melanoma.23

Total body irradiation, as was used in Patient 2, has been associated with a 2.7 to 4.4-fold higher risk of second neoplasms, with a positive dose relationship.24 The latency period from time of radiation treatment to development of the second neoplasm may be up to 50 years after exposure.25 Guerin et al demonstrated that the risk of melanoma was found to be linked to the local radiation dose, with an increased risk noted specifically for local radiation doses > 15 Gy.22 Patient 1 received a dose of 66 Gy to a left parotid and cervical field, while Patient 2 received 12 Gy of TBI plus 48.6 Gy to a cervical spine field. A considerable number of SMNs occurring after radiotherapy do not occur within the irradiated field.26

A genetic basis for disease could also be considered in Patient 2, given his multiple atypical appearing nevi and the family history of melanoma in his mother. Four melanoma susceptibility genes have been characterized including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A, also called p16), alternate reading frame (ARF, also called p14), cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), and melanocortin 1 receptor gene (MC1R).27 Approximately 20-40% of melanoma families carry a mutation in p16/ARF, and only 1-2% of families carry a mutation of CDK4 or ARF-only genes.27 Genetic studies have not been performed in these patients but will be considered in the future.

Some familial melanoma syndromes are associated with other cancers including pancreatic cancer and neural tumors. The melanoma-neural system tumor syndrome is a familial syndrome composed of multiple primary melanomas as well as tumors of neural origin including acoustic neurilemmomas, meningiomas, astrocytomas, medulloblastomas, glioblastoma multiforme, and others.28 Mutations involving ARF-alone29 or involving a region of chromosome 9p21 encompassing CDKN2A, CDKN2B (also called p15), and ARF genes30 have been identified in the melanoma-neural system tumor syndrome. With the personal history of both a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and radiographic evidence of an acoustic neurilemmoma in Patient 2, strong consideration should be given to the melanoma-neural system tumor syndrome.

We present these 2 patients with diagnosis of HHD, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. We hope to draw awareness to this association of HHD and cancer, and if similar cases are recognized, then additional genetic and molecular studies may be performed to elucidate the mechanism of carcinogenicity in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: none

Abbreviations

- HHD

Hailey-Hailey disease

- AMoL

acute monoblastic leukemia

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- SMN

secondary malignant neoplasm

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Reprints: not available

Authorship Responsibility and Contributions:

Drs. Mohr, Erdag, Shada, Williams, Slingluff, and Patterson had full access to all of the data in the report and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Drs. Mohr, Erdag, and Shada

Acquisition of data: Drs. Mohr, Erdag, and Shada

Analysis and interpretation of data: Drs. Mohr, Erdag, Shada, Williams, Slingluff, and Patterson

Drafting of the manuscript: Drs. Mohr, Erdag, and Shada

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Drs. Mohr, Erdag, Shada, Williams, Slingluff, and Patterson

Statistical analysis: not applicable

Obtained funding: not applicable

Administrative, technical, or material support: Drs. Slingluff and Patterson

Study supervision: Drs. Slingluff and Patterson

References

- 1.Hailey H, Hailey H. Report of 13 cases in 4 generations of a family and report of 9 additional cases in 4 generations of a family. Arch Derm Syph. 1939;39:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge S. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992 Mar;126(3):275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holst V, Fair K, Wilson B, Patterson J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Aug;43(2 Pt 2):368–371. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.100542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peluso A, Bonifas J, Ikeda S, et al. Narrowing of the Hailey-Hailey disease gene region on chromosome 3q and identification of one kindred with a deletion in this region. Genomics. 1995 Nov;30(1):77–80. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Z, Bonifas J, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000 Jan;24(1):61–65. doi: 10.1038/71701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudbrak R, Brown J, Dobson-Stone C, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by mutations in ATP2C1 encoding a novel Ca(2+) pump. Hum Mol Genet. 2000 Apr;9(7):1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szigeti R, Kellermayer R. Hailey-Hailey disease and calcium: lessons from yeast. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Dec;123(6):1195–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slingluff CJ, Vollmer R, Seigler H. Multiple primary melanoma: incidence and risk factors in 283 patients. Surgery. 1993 Mar;113(3):330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun S, Whang K, Su W. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in Hailey-Hailey disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1988 Aug;15(4):234–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockayne S, Rassl D, Thomas S. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in Hailey-Hailey disease of the vulva. Br J Dermatol. 2000 Mar;142(3):540–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirai A, Naka W, Kitamura K. A case of squamous cell carcinoma developed in the lesion of Hailey-Hailey's disease. Rinsyo Derma (Tokyo) 1983;25:205–210. al. e. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inaba Y, Mihara I, Tanioka S. Squamous cell carcinoma and Bowen's carcinoma arising in the lesion of Hailey-Hailey disease. Jpn J Clin Dermatol. 1991;45:557–560. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitar A, Giroux J. Treatment of benign familial pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey) by skin grafting. Br J Dermatol. 1970 Sep;83(3):402–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1970.tb15725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furue M, Seki Y, Oohara K, Ishibashi Y. Basal cell epithelioma arising in a patient with Hailey-Hailey's disease. Int J Dermatol. 1987 Sep;26(7):461–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochiai T, Honda A, Morishima T, Sata T, Sakamoto H, Satoh K. Human papillomavirus types 16 and 39 in a vulval carcinoma occurring in a woman with Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999 Mar;140(3):509–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okunade G, Miller M, Azhar M, et al. Loss of the Atp2c1 secretory pathway Ca(2+)-ATPase (SPCA1) in mice causes Golgi stress, apoptosis, and midgestational death in homozygous embryos and squamous cell tumors in adult heterozygotes. J Biol Chem. 2007 Sep;282(36):26517–26527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capiod T, Shuba Y, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Calcium signalling and cancer cell growth. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:405–427. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cialfi S, Oliviero C, Ceccarelli S, et al. Complex multipathways alterations and oxidative stress are associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 2009 Nov; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinnix C, Lee J, Liu Z, et al. Active Notch1 confers a transformed phenotype to primary human melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2009 Jul;69(13):5312–5320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jazbec J, Todorovski L, Jereb B. Classification tree analysis of second neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corpron C, Black C, Ross M, et al. Melanoma as a second malignant neoplasm after childhood cancer. Am J Surg. 1996 Nov;172(5):459–461. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00221-8. discussion 461-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guérin S, Dupuy A, Anderson H, et al. Radiation dose as a risk factor for malignant melanoma following childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003 Nov;39(16):2379–2386. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00663-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao R, Holtan S, Ingle J, et al. Combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2006 Jan;106(2):375–382. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis R, Rowlings P, Deeg H, et al. Solid cancers after bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1997 Mar;336(13):897–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston D, Shimizu Y, Pierce D, Suyama A, Mabuchi K. Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: Solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950-1997. Radiat Res. 2003 Oct;160(4):381–407. doi: 10.1667/rr3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulino A, Fowler B. Secondary neoplasms after radiotherapy for a childhood solid tumor. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005 Mar;22(2):89–101. doi: 10.1080/08880010590896459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pho L, Grossman D, Leachman S. Melanoma genetics: a review of genetic factors and clinical phenotypes in familial melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006 Mar;18(2):173–179. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000208791.22442.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azizi E, Friedman J, Pavlotsky F, et al. Familial cutaneous malignant melanoma and tumors of the nervous system. A hereditary cancer syndrome. Cancer. 1995 Nov;76(9):1571–1578. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1571::aid-cncr2820760912>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randerson-Moor J, Harland M, Williams S, et al. A germline deletion of p14(ARF) but not CDKN2A in a melanoma-neural system tumour syndrome family. Hum Mol Genet. 2001 Jan;10(1):55–62. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahuau M, Vidaud D, Kujas M, et al. Familial aggregation of malignant melanoma/dysplastic naevi and tumours of the nervous system: an original syndrome of tumour proneness. Ann Genet. 1997;40(2):78–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]