Abstract

The transpeptidation reaction catalyzed by bacterial sortases continues to see increasing use in the construction of novel protein derivatives. In addition to growth in the number of applications that rely on sortase, this field has also seen methodology improvements that enhance reaction performance and scope. In this opinion, we present an overview of key developments in the practice and implementation of sortase-based strategies, including applications relevant to structural biology. Topics include the use of engineered sortases to increase reaction rates, the use of redesigned acyl donors and acceptors to mitigate reaction reversibility, and strategies for expanding the range of substrates that are compatible with a sortase-based approach.

Introduction

The manipulation of protein structure in ways beyond the reach of standard genetic approaches is a critical activity in the modern biochemical sciences. Among the numerous reported approaches for protein derivatization, the transpeptidation reaction catalyzed by bacterial sortases, a process referred to as sortagging, has attracted attention because of its ease of use and broad scope with respect to both protein targets and the types of modifications installed. In its most common form, sortagging involves the pairing of sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus (SrtAstaph) with an LPXTG-containing substrate (Figure 1). In the presence of Ca2+, the active site cysteine of SrtAstaph cleaves between threonine and glycine to generate a thioester-linked acyl enzyme intermediate. This intermediate is then intercepted by an aminoglycine nucleophile, resulting in the site-specific ligation of the acyl donor and acceptor. Since the introduction of this strategy in 2004, a remarkably diverse set of components has been shown to be compatible with this system [1]. This includes acyl donors and acceptors such as proteins and synthetic peptides, as well as similar types of molecules displayed on solid supports and on the surface of live cells. Recent examples include the synthesis of camelid-derived antibody fragment conjugates for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma, the installation of non-isotopically labeled protein domains to facilitate NMR analysis of proteins with limited solubility, the construction of immuno-PET reagents for non-invasive cancer imaging, and the preparation of multifunctional protein nanoparticles [2–5]. This is by no means an exhaustive list, and we refer the reader to other excellent reviews for more comprehensive discussions of sortagging applications [6–10]. Rather than focus on applications, our goal for this review is to provide an overview of advances in sortagging methodology itself. This includes the engineering and optimization of new reaction materials and reagents, as well as novel reaction systems designed to facilitate the sortagging process. To highlight these strategies, the application of sortagging to challenges in structural biology is also discussed.

Figure 1.

Protein modification via sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation (‘sortagging’).

Optimizing SrtAstaph Performance

Prior to 2011, the vast majority of sortagging applications relied on wild-type sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus (SrtAstaph), typically employed as a soluble fragment lacking either the first 25 or 59 residues. While this enzyme continues to see consistent use, it suffers from some notable limitations: poor reaction rates and a dependency on a Ca2+ cofactor. To circumvent these issues, a number of strategies have now been reported that describe ways to maximize SrtAstaph performance, either through engineering of the enzyme itself, the use of sortase-reactant fusions, or alternate reaction protocols.

With regard to engineered sortases, Chen and co-workers used a directed evolution screen to identify sortase variants with enhanced catalytic activity [11•]. The integration of five underlying mutations (P94R/D160N/D165A/K190E/K196T) in a single gene resulted in the so-called SrtAstaph pentamutant, which exhibited a ~120 fold increase in kcat/KM relative to wild-type SrtAstaph. These mutations are localized near the LPXTG-binding groove, likely improving substrate binding. The pentamutant was subsequently enhanced by adding two additional mutations known to eliminate Ca2+ dependency [12]. Two SrtAstaph heptamutants have been described which add either E105K/E108A mutations or E105K/E108Q mutations to the SrtAstaph pentamutant backbone [13•, 14, 15•]. These variants no longer require Ca2+, and also retain much of the enhanced rate characteristics of the SrtAstaph pentamutant. In the most recent example of SrtAstaph directed evolution, an in vitro compartmentalization strategy was employed to identify a new Ca2+-independent SrtAstaph mutant [16]. A variant with 12 mutations was identified, including E105V and E108G, which are positions known to be involved in Ca2+ binding, and are also mutated in the SrtAstaph heptamutants. In the absence of Ca2+, this particular derivative displayed slightly improved activity relative to wild-type SrtAstaph in the presence of Ca2+. Overall, evolved versions of SrtAstaph offer substantial advantages over the wild-type enzyme, and the heptamutants may represent the most universally potent sortase variants described to date. The pentamutant and heptamutant versions have also seen increasing use in demanding processes such as cell surface labeling and intracellular ligations [11•, 13•, 17, 18]. However, the pentamutant and heptamutant might not be optimal for all applications. While direct comparisons of these mutants to wild-type SrtAstaph have clearly shown enhanced reaction rates, the wild-type enzyme was actually observed to give higher overall yields in the ligation of GFP to triglycine-coated polystyrene beads [19]. Furthermore, the pentamutant was prone to higher levels of undesired hydrolytic and oligomeric side products if reaction progress was not carefully monitored [20]. In addition to evolved SrtAstaph mutants, other notable engineered derivatives include a cyclized SrtAstaph analogue that exhibited improved resistance to chemical denaturation, as well as semisynthetic analogues containing selenocysteine (Sec) or homocysteine (Hcy) in the active site [21–23]. While both Sec and Hcy derivatives showed impaired catalytic activity, this study does provide a compelling route for accessing unconventional SrtAstaph derivatives. A summary of the engineered SrtAstaph variants discussed in this section is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Engineered SrtAstaph Variants with Altered Catalytic Activity / Stability

| Enzyme | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type SrtAstaph | - |

|

[1,8–9] |

| SrtAstaph pentamutant (P94R/D160N/D165A/ K190E/K196T) |

|

|

[11•] |

| SrtAstaph dual mutant (E105K/E108A or E105K/E108Q) |

|

|

[12] |

| SrtAstaph heptamutant |

|

|

[13•,14,15•] |

| cyclo-SrtAstaph |

|

- | [21–22] |

| SrtAstaph mutant (12 point mutations) |

|

- | [16] |

| Sec/Hcy-SrtAstaph (Sec = selenocysteine, Hcy = homocysteine) |

|

|

[23] |

In addition to alterations of the enzyme itself, the use of fusions involving SrtAstaph and either the aminoglycine acyl acceptor or the LPXTG acyl donor have also been reported. Both N- and C-terminal fusions have been described, typically in the context of new approaches for recombinant protein expression and purification [3, 24–30]. Of these, fusions at the N-terminus are particularly intriguing as it has been suggested that the N-termini of these constructs can access the enzyme active site in an intramolecular fashion, thereby driving transpeptidation due to the increase in local reactant concentration [3, 27, 30]. As an example, Amer et al. demonstrated an increase in ligation rates when a construct consisting of wild-type SrtAstaph fused at its N-terminus to an aminoglycine-containing SUMO module was reacted with a separate LPXTG substrate [3]. In this case, reaction rates involving the SUMO-SrtAstaph fusion were significantly enhanced relative to a control reaction involving separate SrtAstaph, aminoglycine SUMO, and LPXTG substrate.

A final area of note concerns the use of affinity purification/immobilization strategies to streamline sortagging protocols. It is well established that the removal of reaction by-products or residual sortase enzyme can be achieved through the strategic inclusion of His6 affinity handles, or the use of the elastin-like polypeptide as a controlled solubility switch [3, 26, 27, 31]. SrtAstaph has also been covalently immobilized on sepharose or PEGA resins to facilitate enzyme removal and enzyme recycling [14, 32]. A useful extension of sortase-immobilization has been the construction of flow-based systems in which reactants are passed over immobilized sortase columns [14, 33]. The flow-based reactor described by Pentelute and coworkers is particularly noteworthy in that the authors demonstrated that flow-based sortagging increased isolated product yields, and reduced contamination by hydrolytic, cyclic, or oligomeric by-products relative to analogous reactions performed using a standard solution-phase protocol [33].

Driving Ligation Product Formation

Sortagging reactions are reversible: the desired ligation product encloses an intact LPXTG acyl donor motif and the released nucleophilic fragment contains an aminoglycine acyl acceptor. To achieve high yields of the ligation product, a significant surplus of one of the reactants is typically added [31, 34]. While effective, this strategy is problematic if the ligation partner used in excess is challenging to synthesize, expensive or only available in limited quantities. To circumvent the need for excess reagents, a growing number of strategies are now available that dramatically improve sortagging yields when ligation partners are used at nearly equimolar concentrations.

A common cause for reversibility in standard sortagging reactions is the accumulation of the released aminoglycine peptide fragment. The physical removal of this by-product thus provides a simple way to limit reaction reversibility. Indeed, sortagging reactions conducted under dialysis conditions or in centrifugal filtration units can significantly enhance reaction conversion through selective removal of low molecular weight aminoglycine by-products [35–38]. Similarly, affinity immobilization strategies combined with sortase-substrate fusions or the aforementioned flow-based sortagging platform have been shown to minimize the need for excess reagents through the selective removal of various reaction components [27, 33]. All of these approaches are straightforward, and typically do not require changes in the sortase substrate recognition site. Notably, some of these techniques have proven particularly useful for the construction of segmentally labeled proteins for NMR analysis [36–38].

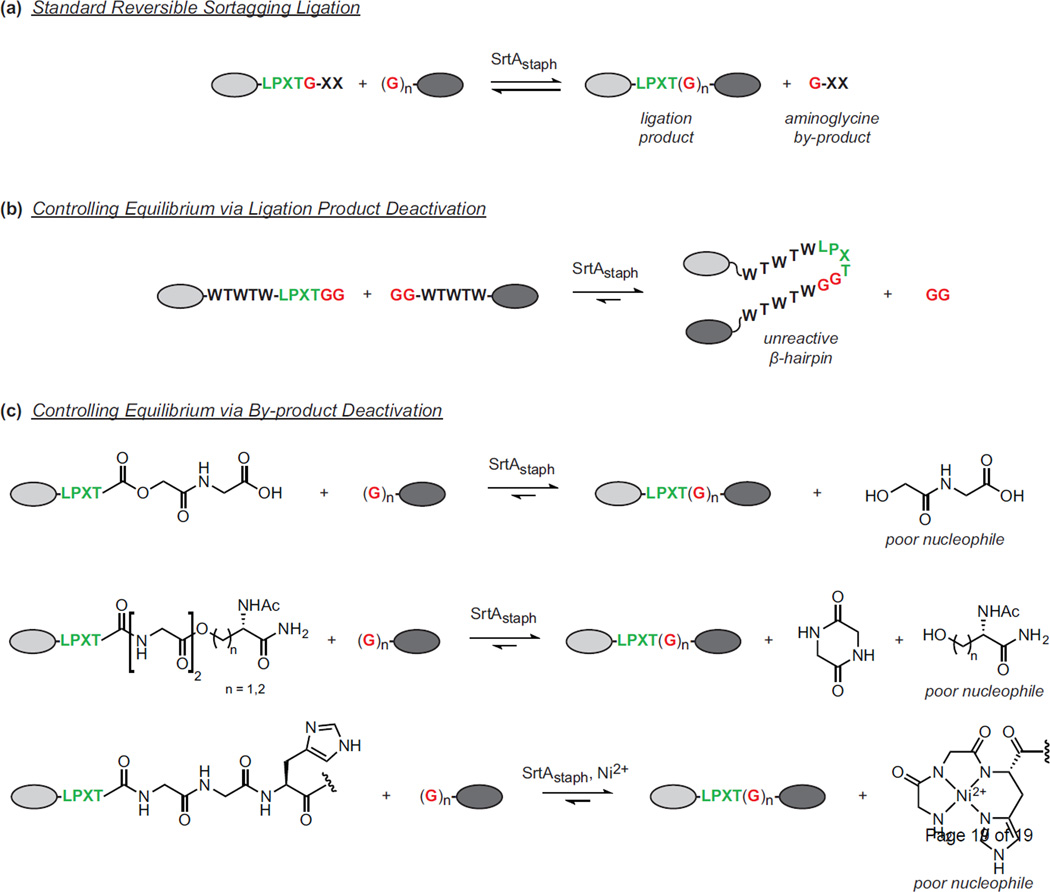

In addition to separation strategies, the designs of both the LPXTG acyl donor and aminoglycine acyl acceptor have been revisited to improve ligation yields. Conceptually, these systems involve selective deactivation of either the sortagging ligation product or other by-products to prevent reverse transpeptidation (Figure 2). Deactivation of the ligation product has been achieved through the formation of an unreactive β-hairpin at the LPXTG ligation site (Figure 2b) [13•, 39]. This secondary structure element inhibits SrtAstaph recognition of the reassembled LPXTG motif, allowing accumulation of the desired ligation product. This approach requires the installation of several additional residues flanking the LPXTG motif, and boosts ligation yields both in vitro and in the cytoplasm of E. coli. With respect to by-product deactivation, LPXTG variants have been designed that release unreactive fragments during formation of the desired sortagging product (Figure 2c). Wiliamson et al. reported the synthesis of a depsipeptide that releases a relatively unreactive hydroxyacetyl moiety instead of a nucleophilic aminoglycine [40, 41• 42]. A second depsipeptide was synthesized by Liu and coworkers that involves release of a fragment that spontaneously deactivates via diketopiperazine formation [43]. These systems, which are best suited for N-terminal labeling, give excellent ligation yields with a variety of protein and peptide targets using only 1.0–3.0 equivalents of depsipeptide acyl donor. A final strategy for by-product deactivation involves Ni2+ chelation. The extension of the LPXTG motif with glycine and histidine (LPXTGGH) results in the release of a GGH-containing fragment that binds with high affinity to bivalent metal ions such as Ni2+ [44]. Coordination of the nitrogen lone pair by Ni2+ minimizes nucleophilicity, thereby limiting the reverse reaction. Due to the fact that this system relies on natural amino acids, it is compatible with both N-terminal and C-terminal sortagging, and has been shown to enhance ligation yields for both peptide and protein model systems at near equimolar concentrations of LPXTG substrate and aminoglycine nucleophile.

Figure 2.

Driving sortagging efficiency through selective deactivation of the ligation product or the ligation by-product. (a) Standard ligations using LPXTG substrates and aminoglycine nucleophiles are reversible, necessitating the need for excess reagents or the continuous removal of the aminoglycine by-product. (b) Selective formation of a β-hairpin deactivates the ligation product and prevents it from engaging in the reverse reaction. (c) Modified acyl donors release by-products that are unable to serve as nucleophiles in the reverse transpeptidation reaction.

Broadening the Substrate Scope

The selective activation of the LPXTG motif by wild-type SrtAstaph or engineered SrtAstaph mutants is the foundation of the majority of sortase-mediated applications. While this selectivity is critical to the success of sortagging applications, in particular ligations performed in complex lysates or on the surface of live cells, it also restricts the technique to substrates that inherently possess the LPXTG motif or those that have been engineered to display this peptide sequence. To address this limitation, a handful of strategies have been reported for expanding sortagging beyond the LPXTG sequence.

One approach to broadening substrate scope involves the use of naturally occurring sortase homologs. To date, two sortase homologs in addition to SrtAstaph have been explored for sortagging-type applications. Sortase A from Streptococcus pyogenes (SrtAstrep), which is Ca2+-independent, can recognize an LPXTA substrate in addition to LPXTG, and accommodates N-terminal alanine residues as acyl acceptors. This subtle difference in substrate tolerance for SrtAstrep has been exploited for applications such as dual labeling of the N-and C-termini in the same polypeptide, and orthogonal labeling of different proteins in the M13 viral particle [45–47]. Due to the lack of Ca2+ dependency, this enzyme has also proven effective for catalyzing ligations in live cells [48, 49]. In addition to SrtAstrep, there has been a single report on the use of sortase A from Lactobacillus plantarum (SrtAplant) [50]. While the yield of ligations using SrtAplant was not reported, this enzyme was shown to catalyze transpeptidations involving non-amino acid primary amine nucleophiles and model proteins possessing LAATGWM, LPKTGDD, and LPQTSEQ sequences. As a final comment, it is also important to note that wild-type SrtAstaph tolerates select deviations from the LPXTG motif. Low to moderate reaction conversions have been observed with the alternate substrates IPKTG, MPXTG, LAETG, LPXAG, LPESG, LPELG, and LPEVG [26, 30, 51]. While these substrates give reduced reaction rates relative to LPXTG, this feature has actually proven beneficial in modulating the rate of self-cleavage in a ternary sortase fusion protein designed as part of a novel strategy for recombinant protein purification [26].

In addition to natural sortases, gains in substrate scope have been achieved using SrtAstaph mutants. Schwarzer and coworkers used a phage display selection system to identify a SrtAstaph mutant (designated F40) with the ability to tolerate a range of XPKTG motifs [30]. The mutant exhibited a slight preference for APKTG, DPKTG, and SPKTG, though trace levels of reactivity were observed for a wide range of other XPKTG substrates, as well as FAKTG. In an elegant demonstration of the utility of this increased substrate scope, the authors reported a semisynthesis of histone H3 involving transacylation at an APATG ligation site. A more recent example of sortase engineering was reported by Dorr et al., who employed a yeast display system to identify two SrtAstaph mutants with altered selectivity profiles [52••]. Starting from the SrtAstaph pentamutant, which itself has some ability to accept LPEXG (X = A, C, S) and LAETG in addition to LPXTG, the authors were able to evolve one mutant (designated 2A-9) with excellent selectivity for LAETG and a second mutant (designated 4S-9) with a preference for LPEXG (X = A, C, S) [20, 52••]. Notably, both engineered sortases showed dramatically reduced activity toward the LPXTG motif, indicating that the mutants were not simply more promiscuous, but rather exhibited substrate selectivity profiles that were orthogonal to wild-type and pentamutant SrtAstaph. The value of these orthogonal sortase mutants was subsequently demonstrated in a variety applications, including site-specific labeling at the N- and C-termini of FGF1 and FGF2, the labeling of endogenous fetuin (which naturally possesses a LPPAG motif) in human plasma, and selective surface modification. A summary of alternate sortase substrates discussed in this section is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Alternate Sortase Substrates

| Enzyme | Substrates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| wild-type SrtAstaph | LPXTG, IPKTG, MPXTG, LAETG, LPXAG, LPESG, LPELG, LPEVG |

|

| wild-type SrtAstrep | LPXTG, LPXTA | |

| wild-type SrtAplant | LAATGWM, LPKTGDD, LPQTSEQ |

|

| F40 SrtAstaph mutant | XPKTG (X = A, D, S), APATG |

|

| SrtAstaph pentamutant | LPXTG, LPEXG (X = A, C, S), LAETG | |

| 2A-9 SrtAstaph mutant | LAETG |

|

| 4S-9 SrtAstaph mutant | LPEXG (X = A, C, S) |

|

Application Highlight: Construction of Protein Fusions for Structural Characterization

The ability of sortases to site-specifically ligate complex polypeptide fragments has made them ideal tools for generating unique protein fusions for crystallographic and NMR characterization. For example, sortase-mediated ligation of HLA-DM to peptide-conjugated HLA-DR1 enabled determination of the X-ray crystal structure of the entire complex, providing new insight into the mechanism by which HLA-DM stabilizes empty HLA-DR1 and catalyzes the exchange of peptides bound by HLA-DR1 [53]. Notably, cocrystallization of separate HLA-DM and HLA-DR1 was unsuccessful, and suitable crystals were obtained only after covalent ligation of these molecules via sortagging. With regard to NMR, sortagging has found use in segmental isotope labeling, wherein an isotopically-enriched protein fragment is ligated to an NMR “silent” fragment. Examples include the attachment of unlabeled solubility enhancing tags (GB1, SUMO), as well as the construction of multidomain proteins (MecA, TIA-1, Hsp90, BRD4) where only certain domains are isotopically labeled to simplify the complexity of NMR spectra [3, 36–38, 54]. Interestingly, the particular challenges of segmental labeling have provided excellent opportunities for refining sortagging methods. Specifically, to boost the yields of ligations involving costly isotopically labeled proteins, nearly all segmental labeling applications using sortase have employed strategies for biasing reaction equilibrium through either dialysis or centrifugal filtration to remove the low molecular weight aminoglycine by-products [36–38, 54]. In addition, to avoid aggregation or degradation of isotopically labeled proteins that may occur during long reaction times, new approaches for increasing sortagging reaction rates have been developed that include the use of centrifugal filtration units, or the use of a novel sortase construct involving the fusion of an aminoglycine acyl acceptor at the N-terminus of wild-type SrtAstaph [3, 38].

Conclusions and Future Directions

Sortagging has benefitted from technical refinements that now offer the end user a range of options when implementing this strategy. We envision that the techniques described here will see increased use, and will enable the next generation of sortase-based applications. With this in mind, this review would not be complete without commenting on emerging areas for application development. One area involves the site-specific construction of isopeptide bonds. Sortagging is typically restricted to protein termini; however, in 2015 Bellucci et al. demonstrated the ability of SrtAstaph to catalyze ligations targeted to specific lysine-containing acceptor sequences embedded in proteins, thereby providing a new route to accessing branched polypeptides [55]. A second area for innovation involves intracellular sortagging. A handful of reports have now demonstrated sortagging with Ca2+-independent sortases in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic systems, although controlling side reactions and introducing exogenous reaction components (acyl donors or acyl acceptors) remains a challenge [13•, 16, 48, 49]. Finally, we also envision an increase in sortase application development to address open questions in structural biology. A particularly powerful aspect of sortagging is its ability to generate protein architectures that cannot be accessed using standard genetic methods. In addition to the isopeptide linked structures discussed above, this also includes complexes where proteins are linked via their respective C- or N-termini to give non-natural C-to-C or N-to-N fusions, such as the HLA-DM-HLA-DR1 complex described by Pos et al. [53, 56, 57]. Going forward, we speculate that the continued development of isopeptide ligations, intracellular sortagging and novel protein fusions will benefit from many of the methodology advances described in this review.

A final notable development, apart from sortase, has been the emergence of the ligase butelase-1 isolated from Clitoria ternatea [58•, 59, 60]. First described in 2014, butelase-1 has been shown to promote cyclizations and intermolecular ligations analogous to those catalyzed by sortases. Butelase-1 also offers some key advantages, including a smaller acyl donor motif (NHV versus LPXTG) and substantially higher reaction rates. Given these attractive features, it is likely that this enzyme will see increased use as an important alternative to sortases, and an intriguing possibility may be the combination of sortagging technology with butelase- or intein-mediated ligation to perform sequential ligations and ultimately generate more complex protein conjugates.

Highlights.

Sortase-catalyzed ligation is a powerful strategy for protein modification.

Engineered sortases improve reaction rates and eliminate Ca2+ dependency.

Deactivation of ligation reaction products minimizes the need for excess reagents.

Sortase mutants and sortase homologs expand the range of compatible substrates.

Acknowledgments

JMA gratefully acknowledges support from Western Washington University and the Research Corporation for Science Advancement. MCT is a recipient of an Advanced Postdoc. Mobility fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). HLP acknowledges support from NIH grant R01 AI087879.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Nothing declared for JMA and MCT. HLP is a co-founder of and owns stock in 121Bio, a company that uses sortase for protein modification.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Mao H, Hart SA, Schink A, Pollok BA. Sortase-mediated protein ligation: a new method for protein engineering. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2670–2671. doi: 10.1021/ja039915e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang T, Duarte JN, Ling J, Li Z, Guzman JS, Ploegh HL. Structurally Defined αMHC-II Nanobody-Drug Conjugates: A Therapeutic and Imaging System for B-Cell Lymphoma. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:2416–2420. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amer BR, Macdonald R, Jacobitz AW, Liauw B, Clubb RT. Rapid addition of unlabeled silent solubility tags to proteins using a new substrate-fused sortase reagent. J Biomol NMR. 2016;64:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0019-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashidian M, Keliher E, Dougan M, Juras PK, Cavallari M, Wojtkiewicz GR, Jacobsen J, Edens JG, Tas JMG, Victora G, et al. The use of (18)F-2-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) to label antibody fragments for immuno-PET of pancreatic cancer. ACS Cent Sci. 2015;1:142–147. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q, Sun Q, Molino NM, Wang S-W, Boder ET, Chen W. Sortase A-mediated multi-functionalization of protein nanoparticles. Chem Commun. 2015;51:12107–12110. doi: 10.1039/c5cc03769g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van 't Hof W, Maňásková SH, Veerman ECI, Bolscher JGM. Sortase-mediated backbone cyclization of proteins and peptides. Biol Chem. 2015;396:283–293. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haridas V, Sadanandan S, Dheepthi NU. Sortase-based bio-organic strategies for macromolecular synthesis. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1857–1867. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritzefeld M. Sortagging: a robust and efficient chemoenzymatic ligation strategy. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:8516–8529. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmohl L, Schwarzer D. Sortase-mediated ligations for the site-specific modification of proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;22C:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voloshchuk N, Liang D, Liang JF. Sortase A Mediated Protein Modifications and Peptide Conjugations. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2015;12:205–213. doi: 10.2174/1570163812666150903115601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen I, Dorr BM, Liu DR. A general strategy for the evolution of bond-forming enzymes using yeast display. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11399–11404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101046108. • This directed evolution study describes a variety of mutations that dramatically improve the in vitro activity of SrtAstaph. This study includes the first report of the SrtAstaph pentamutant. The mutants described in this work have been used in a variety of sortagging applications.

- 12.Hirakawa H, Ishikawa S, Nagamune T. Design of Ca(2+) -independent Staphylococcus aureus sortase A mutants. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2955–2961. doi: 10.1002/bit.24585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirakawa H, Ishikawa S, Nagamune T. Ca2+ -independent sortase-A exhibits high selective protein ligation activity in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:1487–1492. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500012. • This study is one of the first reports of combining mutations that render SrtAstaph Ca2+-independent with mutations that increase SrtAstaph activity. The resulting SrtAstaph heptamutant was shown to be active in a challenging in vivo ligation conducted in the cytoplasm of E. coli. Previous work by these authors identified the mutations that eliminate SrtAstaph Ca2+-dependence [12].

- 14.Witte MD, Wu T, Guimaraes CP, Theile CS, Blom AEM, Ingram JR, Li Z, Kundrat L, Goldberg SD, Ploegh HL. Site-specific protein modification using immobilized sortase in batch and continuous-flow systems. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:508–516. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wuethrich I, Peeters JGC, Blom AEM, Theile CS, Li Z, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, Guimaraes CP. Site-specific chemoenzymatic labeling of aerolysin enables the identification of new aerolysin receptors. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109883. • This study is the first report of the SrtAstaph heptamutant, which combines mutations that eliminate Ca2+-dependency with mutations that increase SrtAstaph activity. At present, this SrtAstaph heptamutant (along with the related heptamutant mentioned in the annotation for [13•]) is arguably the most universally applicable sortase derivative known.

- 16.Gianella P, Snapp E, Levy M. An in vitro compartmentalization based method for the selection of bond-forming enzymes from large libraries. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016 doi: 10.1002/bit.25939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi J, Kundrat L, Pishesha N, Bilate A, Theile C, Maruyama T, Dougan SK, Ploegh HL, Lodish HF. Engineered red blood cells as carriers for systemic delivery of a wide array of functional probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:10131–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409861111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swee LK, Lourido S, Bell GW, Ingram JR, Ploegh HL. One-step enzymatic modification of the cell surface redirects cellular cytotoxicity and parasite tropism. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:460–465. doi: 10.1021/cb500462t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heck T, Pham P-H, Hammes F, Thöny-Meyer L, Richter M. Continuous Monitoring of Enzymatic Reactions on Surfaces by Real-Time Flow Cytometry: Sortase A Catalyzed Protein Immobilization as a Case Study. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:1492–1500. doi: 10.1021/bc500230r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heck T, Pham P-H, Yerlikaya A, Thöny-Meyer L, Richter M. Sortase A catalyzed reaction pathways: a comparative study with six SrtA variants. Catal Sci Tech. 2014;4:2946–2911. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhulenkovs D, Leonchiks A. Staphylococcus aureus sortase A cyclization and evaluation of enzymatic activity in vitro. Environ Exp Biol. 2010;8:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhulenkovs D, Jaudzems K, Zajakina A, Leonchiks A. Enzymatic activity of circular sortase A under denaturing conditions: An advanced tool for protein ligation. Biochem Eng J. 2014;82:200–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmohl L, Wagner FR, Schümann M, Krause E, Schwarzer D. Semisynthesis and initial characterization of sortase A mutants containing selenocysteine and homocysteine. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:2883–2889. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao H. A self-cleavable sortase fusion for one-step purification of free recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;37:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsunaga S, Matsuoka K, Shimizu K, Endo Y, Sawasaki T. Biotinylated-sortase self-cleavage purification (BISOP) method for cell-free produced proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:42–50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellucci JJ, Amiram M, Bhattacharyya J, McCafferty D, Chilkoti A. Three-in-one chromatography-free purification, tag removal, and site-specific modification of recombinant fusion proteins using sortase A and elastin-like polypeptides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:3703–3708. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warden-Rothman R, Caturegli I, Popik VV, Tsourkas A. Sortase-Tag Expressed Protein Ligation (STEPL): combining protein purification and site-specific bioconjugation into a single step. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11090–11097. doi: 10.1021/ac402871k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui JZ, Tamsen S, Song Y, Tsourkas A. LASIC: Light Activated Site-Specific Conjugation of Native IgGs. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:1456–1460. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay ID, Du J, Reyes PR, Rehm BHA. In vivo polyester immobilized sortase for tagless protein purification. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:190–196. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piotukh K, Geltinger B, Heinrich N, Gerth F, Beyermann M, Freund C, Schwarzer D. Directed Evolution of Sortase A Mutants with Altered Substrate Selectivity Profiles. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17536–17539. doi: 10.1021/ja205630g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guimaraes CP, Witte MD, Theile CS, Bozkurt G, Kundrat L, Blom AEM, Ploegh HL. Site-specific Cterminal and internal loop labeling of proteins using sortase-mediated reactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1787–1799. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinhagen M, Zunker K, Nordsieck K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Large scale modification of biomolecules using immobilized sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:3504–3510. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Policarpo RL, Kang H, Liao X, Rabideau AE, Simon MD, Pentelute BL. Flow-based enzymatic ligation by sortase A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:9203–9208. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theile CS, Witte MD, Blom AEM, Kundrat L, Ploegh HL, Guimaraes CP. Site-specific N-terminal labeling of proteins using sortase-mediated reactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1800–1807. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pritz S, Wolf Y, Kraetke O, Klose J, Bienert M, Beyermann M. Synthesis of biologically active peptide nucleic acid-peptide conjugates by sortase-mediated ligation. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3909–3912. doi: 10.1021/jo062331l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobashigawa Y, Kumeta H, Ogura K, Inagaki F. Attachment of an NMR-invisible solubility enhancement tag using a sortase-mediated protein ligation method. J Biomol NMR. 2009;43:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Refaei MA, Combs Al, Kojetin DJ, Cavanagh J, Caperelli C, Rance M, Sapitro J, Tsang P. Observing selected domains in multi-domain proteins via sortase-mediated ligation and NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2011;49:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9464-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freiburger L, Sonntag M, Hennig J, Li J, Zou P, Sattler M. Efficient segmental isotope labeling of multi-domain proteins using Sortase A. J Biomol NMR. 2015;63:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamura Y, Hirakawa H, Yamaguchi S, Nagamune T. Enhancement of sortase A-mediated protein ligation by inducing a β-hairpin structure around the ligation site. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4742–4744. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05334a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson DJ, Fascione MA, Webb ME, Turnbull WB. Efficient N-terminal labeling of proteins by use of sortase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:9377–9380. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williamson DJ, Webb ME, Turnbull WB. Depsipeptide substrates for sortase-mediated N-terminal protein ligation. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.003. • This report provides a very useful overview of the synthesis and use of depsipeptides for improving the efficiency of N-terminal sortagging. This detailed protocol complements the authors’ previous work [40], and notably contains a scaled up synthesis of a key solid phase building block for depsipeptide preparation.

- 42.Morrison PM, Balmforth MR, Ness SW, Williamson DJ, Rugen MD, Turnbull WB, Webb ME. Confirmation of a Protein-Protein Interaction in the Pantothenate Biosynthetic Pathway by Using Sortase-Mediated Labelling. Chembiochem. 2016;17:753–758. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu F, Luo EY, Flora DB, Mezo AR. Irreversible sortase A-mediated ligation driven by diketopiperazine formation. J Org Chem. 2014;79:487–492. doi: 10.1021/jo4024914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.David Row R, Roark TJ, Philip MC, Perkins LL, Antos JM. Enhancing the efficiency of sortasemediated ligations through nickel-peptide complex formation. Chem Commun. 2015;51:12548–12551. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04657b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antos JM, Chew G-L, Guimaraes CP, Yoder NC, Grotenbreg GM, Popp MW-L, Ploegh HL. Site-specific N- and C-terminal labeling of a single polypeptide using sortases of different specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10800–10801. doi: 10.1021/ja902681k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hess GT, Cragnolini JJ, Popp MW, Allen MA, Dougan SK, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, Belcher AM, Guimaraes CP. M13 Bacteriophage Display Framework That Allows Sortase-Mediated Modification of Surface-Accessible Phage Proteins. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:1478–1487. doi: 10.1021/bc300130z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hess GT, Guimaraes CP, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, Belcher AM. Orthogonal labeling of M13 minor capsid proteins with DNA to self-assemble end-to-end multiphage structures. ACS Synth Biol. 2013;2:490–496. doi: 10.1021/sb400019s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strijbis K, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. Protein ligation in living cells using sortase. Traffic. 2012;13:780–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Yamaguchi S, Hirakawa H, Nagamune T. Intracellular protein cyclization catalyzed by exogenously transduced Streptococcus pyogenes sortase A. J Biosci Bioeng. 2013;116:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto T, Takase R, Tanaka T, Fukuda H, Kondo A. Site-specific protein labeling with amine-containing molecules using Lactobacillus plantarum sortase. Biotechnol J. 2012;7:642–648. doi: 10.1002/biot.201100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruger RG, Otvos B, Frankel BA, Bentley M, Dostal P, McCafferty DG. Analysis of the substrate specificity of the Staphylococcus aureus sortase transpeptidase SrtA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1541–1551. doi: 10.1021/bi035920j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dorr BM, Ham HO, An C, Chaikof EL, Liu DR. Reprogramming the specificity of sortase enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13343–13348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411179111. •• This excellent directed evolution study describes the identification of sortase mutants with altered substrate selectivities that are orthogonal to the LPXTG-specificity of wild-type SrtAstaph. In addition, this work describes a range of examples that leverage the altered substrate selectivities of evolved mutants. This report, along with previous directed evolution studies [30], suggests that sortases could be engineered to recognize motifs beyond the range of substrates recognized by naturally occurring sortases.

- 53.Pos W, Sethi DK, Call MJ, Schulze M-SED, Anders A-K, Pyrdol J, Wucherpfennig KW. Crystal structure of the HLA-DM-HLA-DR1 complex defines mechanisms for rapid peptide selection. Cell. 2012;151:1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams FP, Milbradt AG, Embrey KJ, Bobby R. Segmental Isotope Labelling of an Individual Bromodomain of a Tandem Domain BRD4 Using Sortase A. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bellucci JJ, Bhattacharyya J, Chilkoti A. A noncanonical function of sortase enables site-specific conjugation of small molecules to lysine residues in proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:441–445. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Witte MD, Cragnolini JJ, Dougan SK, Yoder NC, Popp MW, Ploegh HL. Preparation of unnatural N-to-N and C-to-C protein fusions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11993–11998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205427109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Witte MD, Theile CS, Wu T, Guimaraes CP, Blom AEM, Ploegh HL. Production of unnaturally linked chimeric proteins using a combination of sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation and click chemistry. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1808–1819. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nguyen GKT, Wang S, Qiu Y, Hemu X, Lian Y, Tam JP. Butelase 1 is an Asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:732–738. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1586. • This study is the first report of butelase-1 from Clitoria ternatea. This enzyme is able to catalyze ligations similar to those enabled by sortases. Butelase-1, however, also offers the advantages of substantially improved reaction rates and a shorter acyl donor sequence. Butelase-1 offers a compelling complement to existing sortase-based methods.

- 59.Nguyen GKT, Kam A, Loo S, Jansson AE, Pan LX, Tam JP. Butelase 1: A Versatile Ligase for Peptide and Protein Macrocyclization. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:15398–15401. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen GKT, Cao Y, Wang W, Liu C-F, Tam JP. Site-Specific N-Terminal Labeling of Peptides and Proteins using Butelase 1 and Thiodepsipeptide. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:15694–15698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]