Abstract

Background and Purpose

Research on Arab-Americans as a distinct ethnic group is limited, especially when considering the health of Arab-American youth. This study describes health risk (substance use, violence); health promotive behaviors (hope, spirituality); and sexual activity (oral, vaginal, anal sex) of Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults (15-23 years old) within their life context, as well as the association between these behaviors.

Methods

A secondary analysis of data on a subset of Arab-American participants obtained from a randomized control trial were utilized to conduct mixed methods analyses. Qualitative analyses completed on the open-ended questions used the constant comparative method for a subsample (n=24) of participants. Descriptive quantitative analyses of survey data utilized bivariate analyses and stepwise logistic regression to explore the relation between risk behaviors and sexual activity among the full sample (n=57).

Conclusions

Qualitative analyses revealed two groups of participants: (a) multiple risk behaviors and negative life events, and (b) minimal risk behaviors and positive life events. Quantitative analyses indicated older youth, smokers, and those with higher hope pathways were more likely to report vaginal sex.

Implications for Practice

The unique cultural and social contexts of Arab-American youth provide a framework for recommendations for the prevention of risk behaviors.

According to the most recent United States (U.S.) Census, approximately 1.9 million individuals reported being of Arab descent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). This is likely an underestimate as the Arab-American Institute (AAI) reported in 2012 that there were more than 3.6 million Arab-Americans residing in the U.S. (AAI, 2012). Arab-Americans are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the U.S. (AAI, 2012). Unfortunately, research considering Arab-American youth is limited. In general, Arab-Americans are typically accounted for as White/Caucasians in national surveys (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010) and health-related research among Arab-Americans has largely been conducted with adults (El-Sayed & Galea, 2009). This lack of knowledge is most glaring with respect to sexual activity and sexual health. In the current study, we aim to fill this gap by examining the health risk and sexual behaviors of Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults, and by exploring the relationships between these behaviors.

The Influence of Arab-American Culture and Societal Norms

Cultural and societal norms impact behavior across ethnic groups (Naber, 2006) including Arab-American cultural norms and their impact on adult health and well-being (El-Sayed & Galea, 2009). For example, tobacco use is common in many Arabic countries, informing Arab-Americans’ cultural practices’ as well as beliefs about masculinity and hospitality (Islam & Johnson, 2003). Acculturation studies of Arab-American adults indicate that affiliation with Arabic culture predicted smoking behavior, while demographic factors (e.g., religion, marital status, and age) were strongly associated with acculturation (Jadalla & Lee, 2012). These same researchers found that those who develop strong identification with multiple cultures (i.e., Arabic and American influences) also have poor physical health and well-being outcomes. It is likely that similar influences would exist among Arab-American youth. Indeed, gender norms and expectations such as virility, toughness, chastity, and modesty have a substantial impact on young Arab-Americans (Islam & Johnson, 2003; Yosef, 2008). Some researchers suggest that these cultural norms and expectations may increase expectations for young Arab-American men to engage in health risk behaviors such as smoking (Islam & Johnson, 2003), while hindering young women from discussing issues related to sexual health, family planning, and contraception. As a result, these norms and cultural beliefs may restrict access to adequate healthcare, influence gender preferences for providers, and impact hierarchical decisions related to healthcare (Yosef, 2008).

While Arab-American cultural norms and expectations may increase certain health risks, there may also be a protective quality to these cultural norms which discourages engagement in negative health risk behaviors. For instance, Islamic religious beliefs emphasize the importance and maintenance of physical well-being (Laird, Amer, Barnett, & Barnes, 2007). While the same gender norms and expectations, such as chastity, modesty (Yosef, 2008), and commitment to family relationships (Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000) can be barriers to accessing family planning and sexual health resources for Arab-American womenthey may also influence their decision to remain abstinent before marriage thus decreasing their risk of contracting a sexually transmitted infection (STI) or having an unplanned pregnancy. Indeed, researchers have found that modesty and duty to family promote abstinence before marriage among adolescent girls and young women (Martyn, Reifsnider, Barry, Treviño, & Murray, 2006) and extended family connections and responsibility to one's family can be protective against sexual and other risk behaviors (Martyn et al., 2006; Saftner, Martyn, Momper, Kane Low, & Loveland-Cherry, 2014).

The paucity of knowledge and empirical research regarding the general health, sexual health, and well-being of Arab-American youth informed the objectives of the current study. The purpose of this study is to describe the health risk and sexual behaviors of Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults, as well as the relationships between these different health behaviors. This study is an important and necessary step to better understand potential health-related needs of Arab-American youth and provide them with more culturally tailored and patient-centered preventive healthcare.

Methods

Adolescents and emerging adults are often considered a vulnerable population due to an increased risk for adverse health outcomes (Flaskerud & Winslow, 1998). For instance, the timeframe when youth are transitioning to adulthood is often associated with greater involvement in health-damaging behaviors, higher rates of mortality, and an increase in chronic conditions (Ozer et al., 2012). Furthermore, adolescents and emerging adults often have limited autonomy and knowledge when it comes to making healthcare decisions. However, researchers of topics such as trauma and childhood sexual abuse (Becker-Blease & Freyd, 2006; Newman & Kloupek, 2004) assert that being involved in research about these sensitive experiences can be rewarding and healing for individuals. Qualitative methods such as a life history approach can be meaningful and a positive experience, assisting youth in reflecting on their past behaviors, rather than being damaging or too distressing (Bay-Cheng, 2009). The assessment tool used in this study was originally designed and subsequently modified based on input from a diverse group of youth in order to capture the complexities of working with a vulnerable population around sensitive topics.

Design

Adolescents and emerging adults (n=186) were recruited from three diverse health clinics in the Midwestern U.S. as part of a larger participatory, research-based, randomized control trial designed to test a Sexual Risk Event History Calendar (SREHC) intervention (see Martyn et al., 2016 for additional details of the parent study). This secondary analysis will focus on a subset of this sample that met the inclusion criteria outlined below. Institutional review board approval from all participating institutions was obtained as well as a Certificate of Confidentiality. Participant assent for those under age 18 or consent for those 18 and older was obtained. A wavier of consent from parents was obtained for those under age 18 in order to protect the confidentiality of participants with regard to the risk behaviors and sexual health information they shared.

Participants and Data Collection Procedures

Participants included those who (a) self-identified as Arab-American, (b) were adolescents (ages 15-17) or emerging adults (ages 18-23), and (c) were unmarried. As a result, the present sample (n=57) included Arab-American participants who were about 18 years old (M=17.88, SD=2.21), primarily self-identified as White race (65%), were students (89.5%), lived with their parents (93%), and received public assistance in the form of Medicaid (40.4%) or subsidized lunches (71.9%). Most participants (75.4%) also reported a recent visit (<1 year ago) with their healthcare provider (see Table 1 for detailed demographic information). The majority of participants received healthcare services at a community health clinic. This clinic is the largest and most inclusive Arab community-based health center in the U.S., providing more than 45 different medical and health promotion programs to its patients (ACCESS, 2014). The youth that seek services at the health center are generally second- and third-generation Arab immigrants (ACCESS, 2014).

Table 1.

Demographics of Arab-American Adolescents and Emerging Adults

| Variables % (n) | Total n=57 | Females n=27 | Males n=30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (years) | 17.88 | 18.41 | 17.40 |

| Standard deviation | 2.21 | 2.65 | 1.63 |

| Range | 15-23 | 15-23 | 15-20 |

| Education | |||

| 6-9th grades | 7.0 (4) | 0 (0) | 13.3 (4) |

| 10th grade | 12.3 (7) | 18.6 (5) | 6.7 (2) |

| 11th grade | 29.8 (17) | 25.9 (7) | 33.3 (10) |

| 12th grade/High school grad | 15.8 (9) | 11.1 (3) | 20.0 (6) |

| Some college/ tech school | 26.3 (15) | 37.0 (10) | 16.7 (5) |

| GED | 8.8 (5) | 7.4 (2) | 10.0 (3) |

| Employmenta | |||

| Student | 89.5 (51) | 92.6 (25) | 86.7 (26) |

| Part-time work | 10.5 (6) | 7.4 (2) | 13.3 (4) |

| Full-time work | 14.0 (8) | 22.2 (6) | 6.7 (2) |

| Unemployed | 7.0 (4) | 3.7 (1) | 10.0 (3) |

| Living situationb | |||

| Live with parents | 93.0 (53) | 92.6 (25) | 93.3 (28) |

| Live alone | 3.5 (2) | 3.7 (1) | 3.3 (1) |

| Live with friends | 1.8 (1) | 3.7 (1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Last time you saw a healthcare provider | |||

| Within the last year | 75.4 (43) | 77.8 (21) | 73.3 (22) |

| 1-2 years ago | 12.3 (7) | 14.8 (4) | 10.0 (3) |

| >5 years ago | 1.8 (1) | 3.7 (1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Don't know | 10.5 (6) | 3.7 (1) | 16.7 (5) |

| Health insuranceb | |||

| Medicaid | 40.4 (23) | 48.1 (13) | 33.3 (10) |

| Private | 12.3 (7) | 14.8 (4) | 10.0 (3) |

| None | 15.8 (9) | 25.9 (7) | 6.7 (2) |

| I don't know | 26.3 (15) | 11.1 (3) | 40.0 (12) |

| Eligible for subsidized lunchesb | |||

| Yes | 71.9 (41) | 77.8 (21) | 66.7 (20) |

| No | 24.6 (14) | 22.2 (6) | 26.7 (8) |

Denotes categories where males and females marked more than one response

Indicates missing data

Measures

Sexual Risk Event History Calendar (SREHC)

The SREHC, an open format table using open-ended questions and autobiographical memory and retrieval cycles (Martyn & Belli, 2002), has been used with youth from diverse racial and ethnic groups (Martyn, Darling--Fisher, Smrtka, Fernandez, & Martyn, 2006; Martyn et al., 2013; Saftner et al., 2014). In this study it was used to collect retrospective qualitative data regarding risk and protective health behaviors and communication with clinicians from the intervention participants within the parent study. The SREHC uses prompts such as “What positive events have you had?”, “What is your sexual activity?”, and “Have you had any of these behaviors (alcohol, drugs, cutting, eating problems, others)?” to obtain a history of the past two years, current year, and one year into the future. This allows the clinician using the assessment tool to get a glimpse of the patient's positive and negative life events, activities, relationships, future goals, and health behavior information for each year. This structure allows the SREHC to provide an illustrative view of the individual's health, sexual behavior, and risk behavior history across time within their unique life context.

Sexual experiences and health risk behaviors

Information about the participants’ engagement in sexual behaviors and health risk behaviors (i.e., substance use, physical fighting, carrying weapons, and dating violence) was obtained from survey questions similar to those used on the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS; CDC, 2011). The YRBSS questions assessing risk behaviors and sexual behaviors have demosntrated good test-retest reliability (kappa = 61% - 100%) in two different evaluations completed in 1992 and 2000 (Brener et al., 2013). However, unlike the YRBSS, which only asks about general sexual intercourse, our survey inquired about engagement in specific sexual behaviors (i.e., oral, vaginal, and anal sex; “Have you ever had oral sex [mouth on genitals, penis in mouth]?”). The participants were queried in regards to their engagement and frequency of these different sexual behaviors over the past three months. Due to the small sample size and response rates of each sexual behavior, a composite variable of endorsed sexual behaviors was computed and used in the analyses. The participants were also grouped according to their involvement in certain health risk behaviors including cigarette smoking (occasionally, regularly in past, regularly now); alcohol use (>5 times in life); marijuana use (>5 times in life); and any illicit drug use (cocaine, methampetamine, ectasy).

Hope

The Trait Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1991) was used to measure hope within a goal-setting framework, including items that assess pathways (a belief in one's capability to produce workable routes to goals) and agency (a belief in one's ability to initiate and sustain movement toward those goals). The Trait Hope Scale is a valid and reliable tool that has undergone a rigrous process of development and validation (Snyder et al., 1991). Four questions from each subscale were summed for a total of eight questions (1=definitely false to 4=definitely true); 32 was the highest possible total with higher scores indicating more hope. Overall, the Hope Scale exhibited adequate reliability in our sample (α=.771), as did the pathways subscale (α=.703), and the agency subscale (α=.642).

Spirituality

Four items on a five-point scale (1=not true to 5=very true) were used to measure spirituality (Maton, 1989). A total spirituality score was created by summing all four items; 20 was the highest possible total with higher scores indicating more spirituality. The spirituality scale also demonstrated adequate reliability in our sample (α=.879).

Data Analysis

Mixed methods analyses of the data proceeded in two steps. First, data obtained from the subsample who completed the SREHC (n=24) were used to conduct qualitative analyses in order to identify themes related to the sexual risk behaviors of the participants. Due to randomization procedures of the parent study only half of the sample received the SREHC while the other half received the control assessment, which included a checklist of risk behaviors not suitable for qualitative analysis. This initial phase of qualitative analysis was important in guiding our second phase of quantitative analyses. In the second phase, quantitative analyses were completed to assess all (n=57) participant characteristics, health risk behaviors, and potential protective factors related to sexual behaviors.

Qualitative analysis

The following research question guided the qualitative analyses: “What are the common health risk behaviors and life contexts for Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults?” Using the constant comparative method (Glaser, 1992) common themes of participants’ patterns of sexual and other health risk behaviors within the context of their activities, life events, and relationships were identified. First, the primary investigator and a research fellow achieved consensus on common patterns of risk behaviors. Next, validity checks of themes by other members of the research team were conducted using an audit trail composed of methodological and analytical documentation, which contributed to the validity of this analysis and the final determination of themes. In addition, summative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) of the SREHC data aided in determining the frequency of health risk behaviors reported by the participants. The results of the content analysis were compared to the qualitative themes to enhance the interpretation of the findings.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analyses were guided by the qualitative findings and carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All quantitative data were double-entered for accuracy and all significance values were set at p <.05. Analyses were completed with the full sample (n =57) and began with an evaluation of descriptive characteristics of the sample (Table 1). Bivariate analyses considered the relation between health risk behaviors among the participants who reported any type of sexual activity and those who reported abstinence, as well as associations among health risk behaviors, protective factors, and any sexual activity. After all statistical assumptions were verified a stepwise logistic regression model was used to assess predictors of sexual activity.

Results

Qualitative Results

Qualitative analysis of the contextual data from the SREHC revealed differences in health risk behaviors and contextual factors. Specifically, two groups of Arab-American participants emerged from the data: (a) those with multiple health risk behaviors within the context of significant negative life events coupled with minimal protective factors, and (b) those with minimal health risk behaviors, few negative life events, and strong protective factors.

Multiple risk behavior group

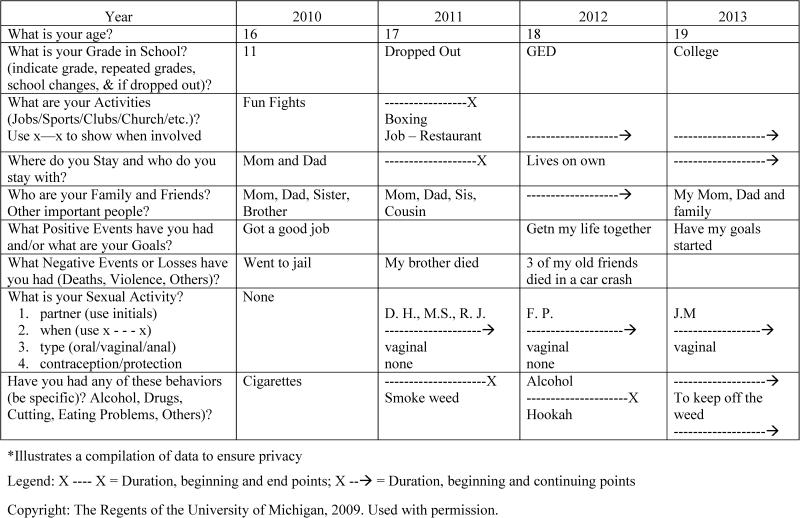

Seven participants who completed the SREHC (7/24; 29.2%) reported engaging in multiple health risk behaviors, five of whom were male. All of the participants in this group were emerging adults who reported being sexually active (i.e., having engaged in oral, vaginal, or anal sex) and having engaged in at least one other health risk behavior such as smoking cigarettes and/or hookah (86%), marijuana use (43%), and alcohol use (71%). Additionally, all but one of the participants in this group reported experiencing at least one significant negative life event such as the death of a close family member or friend (29%), violence or going to jail (29%), dropping out of school (14%), and unspecified “family problems” (14%). Despite members of this group endorsing multiple risks, they all also reported protective factors that were contextually concurrent with episodes of risk behaviors such as: participation in activities (e.g., sports, after-school jobs); support from family and friends; and future goals that focused on furthering their education (i.e., getting a GED, going to college, or continuing college). See Figure 1 for a sample SREHC comprised of responses from the multiple risk behavior group.

Figure 1.

Sample sexual risk event history calendar: Male with multiple risk behaviors

Minimal risk behavior group

There were 17 participants (17/24; 70.8%) who engaged in minimal health risk behaviors. All of these individuals reported being abstinent (i.e., no oral, vaginal, or anal sexual experiences), engaging in positive health behaviors and experiencing positive life events, as well as having strong social networks (e.g., reliable family and friends), academic achievement, and involvement in activities. Individuals in this group also endorsed a variety of healthy activities, behaviors, and/or goals, such as sports or extracurricular activities (83%), going to college or remaining in college (59%), getting good grades (24%), and wanting to become a nurse (24%). As an example, young women in the minimal risk group who reported participation in sports and extracurricular activities did not report any health risk behaviors, sexual or otherwise. Only two individuals (12%) in this group reported a health-risk behavior (i.e., smoking); in each case the act of smoking was concurrent with a negative life experience. Specifically, one participant reported smoking hookah over the course of “fighting with best friend,” while another participant reported smoking after “a classmate committed suicide.”

Quantitative Results

When examining the quantitative data of this study, the full Arab-American sample was utilized (n=57). First, basic descriptive statistics of the participants’ health risk behaviors were conducted, including substance use, physical fighting, carrying weapons, and dating violence, as well as sexual behaviors (Table 2). Associations between sexual activity and different health risk behaviors (cigarette smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, and illicit drug use) and protective factors (hope and spirituality) were examined through bivariate analyses. We examined the correlations between sexual activity, hope, and the hope subscales (pathways and agency). Results from chi-square analyses highlighted that sexually active Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults (n=17) had significantly higher rates of all health risk behaviors measured in this study when compared to those individuals who were abstinent (n=40). Specifically, significant relations were found between sexual activity and cigarette smoking [χ2(df =1)=35.35, p<.001], alcohol [χ2(df=1)=20.98, p<.001], marijuana [χ2(df=1)=20.98, p<.001], and illicit drug use [χ2(df=1)=6.59, p<.01]. Although the relation between sexual activity and hope was not statistically significant, the relation between sexual activity and hope pathways (r=.416, p=.002) was statistically significant. In addition, spirituality and sexual activity were significantly related (r=−.267, p=.051) such that those who reported higher spirituality were less likely to participate in sexual activity.

Table 2.

Risk Behaviors of Arab-American Adolescents and Emerging Adults

| Variables % (n) | Total n=57 | Females n=27 | Males n=30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RISK BEHAVIORS | |||

| Ever smoked cigarettes | |||

| Never | 52.6 (30) | 59.3 (16) | 46.7 (14) |

| Occasionally | 28.1 (16) | 40.7 (11) | 16.6 (5) |

| Regularly | 19.3 (11) | 0 (0.0) | 36.7 (11) |

| Smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (in last 30 days) | 8.8 (5) | 0 (0.0) | 16.7 (5) |

| Times had at least one drink of alcohol | |||

| Never | 75.5 (43) | 85.2 (23) | 66.7 (20) |

| 1-5 times | 7.0 (4) | 3.7 (1) | 10.0 (3) |

| 6-19 times | 7.0 (4) | 0 (0.0) | 13.3 (4) |

| ≥ 20 times | 10.5 (6) | 11.1 (3) | 10.0 (3) |

| Lifetime marijuana use | |||

| Never | 75.5 (43) | 88.9 (24) | 63.4 (19) |

| 1-5 times | 7.0 (4) | 3.7 (1) | 10.0 (3) |

| 6-19 times | 3.5 (2) | 3.7 (1) | 3.3 (1) |

| ≥ 20 times | 14.0 (8) | 3.7 (1) | 23.3 (7) |

| Lifetime illicit drug usea | 8.8 (5) | 7.4 (2) | 10.0 (3) |

| Lifetimes use of someone else's prescription | 21.1 (12) | 14.8 (4) | 26.7 (8) |

|

VIOLENCE | |||

| Physical fight in last 12 months | 28.1 (16) | 18.5 (5) | 36.7 (11) |

| Physical fight that resulted in bandages | 10.5 (6) | 3.7 (1) | 16.7 (5) |

| Carried a knife or razor | 14.0 (8) | 3.7 (1) | 23.3 (7) |

| Carried a gun in the last year | 5.3 (3) | 0 (0.0) | 10.0 (3) |

| Perpetrated dating violenceb | 12.3 (7) | 7.4 (2) | 16.7 (5) |

| Survived dating violenceb | 14.0 (8) | 11.1 (3) | 16.7 (5) |

|

SEXUAL BEHAVIORS | |||

| Oral Sex | 29.8 (17) | 11.1 (3) | 46.7 (14) |

| Vaginal sexc | 22.8 (13) | 7.4 (2) | 36.7 (11) |

| Any type of sexual behaviorc | 29.8 (17) | 11.1 (3) | 46.7 (14) |

| ≥ 5 lifetime sexual partners | 12.3 (7) | 7.4 (2) | 16.7 (5) |

|

FOR THOSE WHO REPORTED VAGINAL INTERCOURSE | |||

| Condom at last intercourse | 61.5 (8) | 50.0 (1) | 63.6 (7) |

| No method used to prevent pregnancy | 30.8 (4) | 50.0 (1) | 27.3 (3) |

Includes cocain, heroin, methamphetamines, and ectasy

Dating violence includes physical, sexual, emotional, or verbal abuse, or intimidation with a weapon

Indicates missing data

Next, the impact of demographic factors (age and biological sex), health risk factors (cigarette smoking), and potential protective factors (hope pathways and spirituality) on participation in oral and vaginal sex was evaluated via stepwise logistic regression models (Table 3). Low rates of participation in anal sex (n=5) resulted in low statistical power for this behavior; therefore, this type of sexual activity was not included in regression models. In the first step, both age and biological sex significantly impacted participation in both oral and vaginal sex. When cigarette smoking was added in the second step, it significantly impacted participation in both oral and vaginal sex. Age remained a significant predictor of both models; however, biological sex only remained a significant predictor for the vaginal sex model. As a final step, potential protective factors were added into the models; cigarette smoking remained a significant predictor of both oral and vaginal sex. Age also remained a significant predictor of vaginal sex, and hope pathways significantly predicted both oral and vaginal sex. Spirituality did not contribute significantly to whether or not individuals engaged in either type of sexual activity. Overall, the most significant predictor of sexual activity was cigarette smoking. The total models accounted for 81.7% of the variance in oral sex and 70.4% of the variance in vaginal sex.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression of Sexual Behaviors (n=53)

| Oral Sex | Vagina Sex | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Demographics | NR2=.467, p<.001 | NR2=.493, p<.001 |

| Age | 2.012* | 2.456* |

| Gendera | 48.492* | 94.390* |

| Step 2: Risk Behaviors | Change in NR2=.284, p<.001 | Change in NR2=.098, p<.019 |

| Age | 2.328* | 2.198* |

| Gendera | 33.355 | 31.982* |

| Cigarette smoking | 64.091* | 8.226* |

| Step 3: Protective Factors | Change in NR2=.066, p=.059 | Change in NR2=.113, p=.028 |

| Age | 2.019 | 2.405* |

| Gendera | 7.537 | 14.457 |

| Cigarette smoking | 209.494* | 18.176* |

| Hope | 2.174* | 2.717* |

| Spirituality | .994 | .988 |

| Final Model | NR2=.817, p<.001 | NR2=.704, p<.001 |

Indicates a significant p-value (p≤.05) for the OR shown

Male=reference category

In sum, participants reported engaging in health risk behaviors on both qualitative and quantitative assessment tools and surveys. Mixed methods analyses of the contextual and health risk behavior data enhanced the interpretation of factors that may have influenced participation in the selected health risk behaviors considered among the Arab-American youth participating in this study. Specifically, the SREHC allowed us to understand the context within which individuals engaged in multiple health risk behaviors. That is, they were more likely to have experienced negative life events and have minimal protective factors in their lives. In contrast, those who reported minimal health risk behaviors were more likely to be abstinent, have experienced positive life events, and have support systems in their lives.

Discussion

In line with some previous research on Arab-American youth, the results of this study indicate that Arab-American adolescents and emerging adults participate in health risk behaviors that may be heavily influenced by cultural factors (Aroian, Templin, Hough, Ramaswamy, & Katz, 2011; Naber, 2006), biological sex, age, and positive and negative life events. We examined our results through a general health risk framework. Accordingly, the Arab-American youth in this sample reported lower rates of sexual activity and higher rates of cigarette use and injury due to physical fighting when compared to other racial groups in the YRBSS national literature (CDC, 2011). Although 70.2% of the Arab-American sample in our study did not report any type of sexual activity (i.e., oral, vaginal, or anal sex) on our surveys, 12.5% of these self-declared abstinent individuals received clinical recommendations from their healthcare provider for pregnancy and/or STI testing. This inconsistency between patient report and clinical recommendations may highlight the significant influence of traditional Arab-American religious and family taboos on the discussion of sexual issues. This inconsistency has also been found in research with non-Arab adolescents whose self-reported abstinence was inconsistent with the results of laboratory-confirmed STI testing (DiClemente, Sales, Danner, & Crosby, 2009).

Our results demonstrate that Arab-American youth have slightly higher rates of smoking compared to national statistics (CDC, 2011). Within our sample, those participants who smoked were more likely to report sexual activity, and the males in our study were more likely than females to report sexual activity, especially when they were older. Together these findings suggest that smoking, particularly for Arab-American males, may be a culturally accepted behavior that has negative health risks, thus warranting further investigation.

Our analyses also suggest that hope and spirituality are associated with sexual behavior, albeit in different ways. Contrary to the literature (Vesely et al., 2004), the pathways aspect of hope appears to serve as a risk factor in this sample, whereby those with higher reported hope pathways scores, or those who had set future goals and aspirations for themselves, were actually more likely to participate in sexual activity. It may be that youth with higher hope pathways scores believe that there are ways to avoid problems prompting them to feel less at risk for sexual health problems related to sexual activity, consistent with the feeling of invincibility during this developmental stage in life (Elkind, 1981).

Alternatively participants who reported more involvement in extracurricular activities and sports reported few to no risk behaviors. Current developmental theories and past work demonstrate the positive benefits of being part of a team, having structured and productive time in one's day, and physical activity including decreased rates of smoking, drinking alcohol, illicit drug use, engagement in violent behaviors, and participation in sexual activity (Jones-Palm & Palm, 2005).

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. The data analyzed were obtained from a larger parent study that was not designed to specifically assess the sexual and general health risk behaviors or to recruit a large sample of Arab-American youth. Therefore, we did not obtain nuanced data regarding differences within and between the Arab-American youth in our sample, and our sample size was small. Not only does this impact our ability to generalize to other Arab-American youth and communities, but it also directed some of our data analytic decisions. For example, we focused on a sample that spanned across two developmental time periods due to the paucity of literature on Arab-American youth and the number of individuals in our sample. Although not ideal, as one of the first attempts to investigate health risk behaviors, especially sexual behaviors, among Arab-American youth, this concession seemed to outweigh the costs associated with combining individuals across developmental periods.

Another limitation of this study involved some of the research tools utilized. Based on conversations with clinic staff and additional reviews of the literature, we believe that the way in which we asked about marital status did not accurately capture the various types of relationships of our Arab-American participants. We used a multiple choice question to assess self-reports of marital status that provided the responses of single, partner, married, or divorced/separated. However, our question did not differentiate between a civil marriage and a religious marriage, a distinction noted to be of importance in the Arab-American community (Hassouneh-Phillips, 2001), as well as different types of intimate relationships that may be of particular relevance for adolescents and emerging adults, some of whom were attending college. Future work should therefore take into consideration a more diverse representation of relationship types, such as the presence of a marriage contract that may create a binding union religiously but not civilly (Hassouneh-Phillips, 2001) as well as developmentally relevant relationships such as “friends with benefits,” “hook-ups,” and other non-romantic sexual relationships (Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006).

We may not have measured all of the potential variables that could be related to sexual initiation and health risk behaviors within this ethnic group. Previous research has found that Arab-Muslim teens learn early in life that certain sexual issues (e.g., safe sex, family planning) are not discussed due to religious beliefs and practices (Yosef, 2008). Furthermore, some findings have indicated that the consideration of acculturation is especially important when providing services to Arab-Americans (Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000). Additionally, the larger parent study did not specifically measure what generation immigrants the youth were. We do know that the majority of youth who seek services at the community health center are second- or third-generation; however, having a specific measure could have helped discern differences based on acculturation. Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence for the necessity to incorporate cultural, contextual, and developmental factors into healthcare visits and research with Arab-American youth.

Clinical Implications

Clinicians play a pivotal role in the assessment of risk and provision of preventive healthcare services for youth. As such, they must be equipped with a thorough understanding of pertinent cultural factors, normative development, contextual influences, and healthcare issues (National Research Council, 2009). Patient-centered approaches to healthcare support culturally responsive care capable of addressing the needs and preferences of Arab-American youth.

The literature provides some guidelines as how to best engage Arab-American clients in their healthcare (e.g., Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000); however, these are not specific to health risk behaviors. Based on our findings and experience working with youth, coupled with the cultural beliefs of modesty and privacy, Arab-American youth may be reluctant to share personal information about high risk behaviors. Clinicians should aim to provide a non-judgemental, confidential environment in order to promote open communication about taboo topics. This could be provided by using a clinical assessment tool like the SREHC, which can be completed by a patient prior to a visit and then reviewed with the provider in a private exam room. The SREHC can provide information about risk behaviors and contextual life experiences in a temporally organized way in order to assist culturally diverse youth in identifying ways in which they can promote their own health with the support of a healthcare professional (Martyn et al., 2016). This approach allows the clinician to address the confidential education needed for all youth with an emphasis on those risks that were particlarly note worthy in this population regarding: (a) safer sex and avoiding sexual risk behaviors, (b) the avoidance of tobacco and other substances as well as the risks of using these substances, and (c) conflict resolution to aid in the prevention of physical fighting. This preventive education needs to take into account the contextual risks (e.g., experiences of ethnic discrimination and/or stereotyping) and protective factors (e.g., strong family ties and/or religious beliefs) present in the patient's life (Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000; Laird et al., 2007). Furthermore, social contexts and risk behaviors are interrelated and the associations between different types of risk behaviors tend to increase with age (Lytle, Kelder, Perry, & Klepp, 1995). It is essential for clinicians to recognize these interrelationships early and provide holistic approaches to preventive care through open discussion guided by knowledge of the patient's culture.

In order to develop and implement culturally tailored care it is first necessary to understand the risks and behaviors of a population. This study has begun to close a gap in the literature regarding the risk behaviors of a distinct cultural group. These results suggest that Arab-American youth have unique health needs that may best be addresssed with culturally tailored care and interventions. Further research is needed regarding the unique cultural and developmental needs of Arab-American youth.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Access Community Health and Research Center, the Washtenaw County Public Health Department, and Eastern Michigan University – University Health Services for their assistance with recruitment and data collection.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health under grant number R34-MH-082644 (PI: Kristy Martyn); support to Michelle Munro was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research under grant number F31NR012852; and support to Sarah Stoddard was provided by a Mentored Scientist Career Development Award, National Institute on Drug Abuse under grant number 1K01 DA 034765.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to authorship or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Michelle L. Munro-Kramer, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 N. Ingalls, Room 3188, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5482.

Nicole M. Fava, Florida International Institute Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC5 505, Miami, FL 33199, Telephone: 305-348-4903, nicole.m.fava@gmail.com.

Melissa A. Saftner, University of Minnesota School of Nursing, 6-165 Weaver-Densford Hall, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0213, Telephone: 218-726-8934, msaftner@umn.edu.

Cynthia S. Darling-Fisher, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 N. Ingalls, Room 3176, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5482, Telephone: 734-647-0328, darfish@umich.edu.

Nutrena H. Tate, Wayne State University College of Nursing, 5557 Cass, 140 Cohn, Detroit, MI 48202, Telephone: 313-557-1754, nutrena.tate@wayne.edu.

Sarah A. Stoddard, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 N. Ingalls, Room 3344, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5482, Telephone: 734-647-0327, sastodda@umich.edu.

Kristy K. Martyn, Director of the Doctor of Nursing Practice Program, Independence Chair in Nursing, Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, 1520 Clifton Road, NE, Rm 336, Atlanta, GA 30322, Telephone: 404-727-6913, kmartyn@emory.edu.

References

- 2014 annual report. 2014 ACCESS Retrieved from https://www.accesscommunity.org/download/file/fid/562.

- Al-Krenawi A, Graham JR. Culturally sensitive social work practice with Arab clients in mental health settings. Health & Social Work. 2000;25(1):9–22. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.9. doi:10.1093/hsw/25.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab American Institute Demographics. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.aaiusa.org/pages/demographics/

- Aroian KJ, Templin TN, Hough EE, Ramaswamy V, Katz A. A longitudinal family-level model of Arab Muslim adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(8):996–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9615-5. doi:1007/s10964-010-9615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Cheng LY. Beyond trickle-down benefits to research participants. Social Work Research. 2009;33(4) [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA, Freyd JJ. Research participants telling the truth about their lived. American Psychologist. 2006;61:218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.218. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kinchen S, Eaton DK, Hawkins J, Flint KH. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(RR01):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1991-2011 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey data. 2011 Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline.

- DiClemente RJ, Sales JM, Danner F, Crosby RA. Association between sexually transmitted diseases and young adults’ self-reported abstinence. Pediatrics. 2009;127(2):208–213. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0892. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D. Children and adolescents: Interpretive essays on Jean Piaget. 3rd. ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed AM, Galea S. The health of Arab-Americans living in the United States: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:272–280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-272. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nursing Research. 1998;47(2):69–78. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hassouneh-Phillips DS. “Marriage is half of faith and the rest if fear Allah”: Marriage and spousal abuse among American Muslims. Violence Against Women. 2001;7(8):927–946. doi:10.1177/10778010122182839. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam SMS, Johnson CA. Correlates of smoking behavior among Muslim Arab-American adolescents. Ethnicity & Health. 2003;8(4):319–337. doi: 10.1080/13557850310001631722. doi:10.1080/13557850310001631722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadalla A, Lee J. The relationship between acculturation and general health of Arab Americans. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2012;23(2):159–165. doi: 10.1177/1043659611434058. doi:10.1177/1043659611434058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Palm DH, Palm J. Physical activity and its impact on health behavior among youth. World Health Organization; 2005. Retrieved from https://www.icsspe.org/sites/default/files/PhysicalActivity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Laird LD, Amer MM, Barnett ED, Barnes LL. Muslim patients and health disparities in the U.K. and the U.S. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2007;92(10):922–926. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.104364. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA, Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI. Covariance of adolescent health behaviors: The Class of 1989 Study. Health Education Research. 1995;10(2):133–146. doi: 10.1093/her/10.2.119-a. doi:10.1093/her/10.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Giordano PC, Longmore MA. Hooking up: The relationship contexts of “nonrelationship” sex. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21(5):459–483. doi:10.1177/0743558406291692. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Belli RF. Retrospective data collection using event history calendars. Nursing Research. 2002;51(4):270–274. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Munro-Kramer ML, Fava NM, Banerjee T, Darling-Fisher >CS, Pardee M, Villarruel AM. The effect of a youth-centered sexual risk event history calendar (SREHC) assessment on sexual risk attitudes, intentions, and behavior. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.09.004. In preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Darling-Fisher C, Smrtka J, Fernandez D, Martyn DH. Honoring family biculturalism: Avoidance of adolescent pregnancy among Latina girls in the United States. Hispanic Health Care International. 2006;4(1):15–26. doi:10.1891/hhci.4.1.15. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Reifsnider E, Barry MG, Treviño MB, Murray A. Protective processes of Latina adolescents. Hispanic Health Care International. 2006;4(2):111–124. doi:10.1891/hhci.4.2.111. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI. The stress-buffering role of spirituality support: Cross-sectional and prospective investigations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1989;28(3):301–323. [Google Scholar]

- Naber N. The rules of forced engagement: Race, gender, and the culture of fear among Arab immigrants in San Francisco post-9/11. Cultural Dynamics. 2006;18(3):235–276. doi:10.1177/0921374006071614. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Adolescent health services: Missing opportunities. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. Retrieved from https://download.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman E, Kaloupek DG. The risks and benefits of participating in trauma-focused research studies. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:383–394. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048951.02568.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EM, Urquhart JT, Brindis CD, Park MJ, Irwin CE. Young adult preventive health care guidelines: There but can't be found. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(3):240–247. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.794. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.7942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftner MA, Martyn KK, Momper SL, Kane Low L, Loveland-Cherry CS. Urban American Indian adolescent girls: Framing sexual risk behavior. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1043659614524789. Online First doi:10.1177/1043659614524789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Harney P. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(4):570–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Race. 2010 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/meta/long_RHI305210.htm.

- Vesely SK, Wyatt VH, Oman RF, Aspy CB, Kegler MC, Rodine S, McLeroy KR. The potential protective effects of youth assets from adolescent sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(5):356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef ARO. Health beliefs, practices, and priorities for health care of Arab Muslims in the United States: Implications for nursing care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008;19(3):284–291. doi: 10.1177/1043659608317450. doi:10.1177/1043659608317450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]