Abstract

Context and Objective:

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by a β-cell deficit due to autoimmune inflammatory-mediated β-cell destruction. It has been proposed the deficit in β-cell mass in T1D may be in part due to β-cell degranulation to chromogranin-positive, hormone-negative (CPHN) cells.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

We investigated the frequency and distribution of CPHN cells in the pancreas of 15 individuals with T1D, 17 autoantibody-positive nondiabetic individuals, and 17 nondiabetic controls.

Results:

CPHN cells were present at a low frequency in the pancreas from nondiabetic and autoantibody-positive, brain-dead organ donors but are more frequently found in the pancreas from donors with T1D (islets: 1.11% ± 0.20% vs 0.26% ± 0.06 vs 0.27% ± 0.10% of islet endocrine cells, T1D vs autoantibody positive [AA+] vs nondiabetic [ND]; T1D vs AA+, and ND, P < .001). CPHN cells are most commonly found in the single cells and small clusters of endocrine cells rather than within established islets (clusters: 18.99% ± 2.09% vs 9.67% ± 1.49% vs 7.42% ± 1.26% of clustered endocrine cells, T1D vs AA+ vs ND; T1D vs AA+ and ND, P < .0001), mimicking the distribution present in neonatal pancreas.

Conclusions:

From these observations, we conclude that CPHN cells are more frequent in T1D and, as in type 2 diabetes, are distributed in a pattern comparable with the neonatal pancreas, implying a possible attempted regeneration. In contrast to rodents, CPHN cells are insufficient to account for loss of β-cell mass in T1D.

In pancreas from humans with type 1 diabetes there is an increase in endocrine cells that express no hormones. This suggests ongoing attempted beta regeneration.

Type 1 diabetes results from insufficient β-cell mass due to autoimmune destruction and afflicts approximately 1 million people in the United States. Although the concept that β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes is a consequence of autoimmunity remains well accepted (1, 2), interesting new concepts have arisen to suggest that the loss of β-cells in type 1 and 2 diabetes may be in part due to the degranulation of β-cells and or transdifferentiation of β-cells to other cell types (3–5). An alternative explanation for the increased presence of hormone-negative endocrine cells in the pancreas in diabetes is that they represent an ongoing attempted β-cell regeneration. Support for this possibility arises from the comparable pattern and distribution of such cells in late gestation and early infancy in humans (6).

To further probe these possibilities, in the present study, we examined the pancreas of brain-dead organ donors with type 1 diabetes vs nondiabetic controls. It has already been established that there is ongoing β-cell turnover in adults with longstanding type 1 diabetes, although the origin of these cells is unknown (7–9). We reasoned that if we identified in humans with type 1 diabetes a comparable pattern of hormone-negative pancreatic endocrine cells to that that we noted in the developing human endocrine pancreas, this would be consistent with the possibility that there are newly forming β-cells in type 1 diabetes.

Therefore, we sought to address the following question: is there an increase in the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells in the pancreas in humans with type 1 diabetes, and, if so, does the pattern mimic that observed in infancy, with a preponderance of distribution as scattered cells within the exocrine pancreas? We were able to approach this issue because of the outstanding repository of human pancreas assembled by the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes (nPOD) consortium based at the University of Florida (Gainesville, Florida).

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

Design and case selection

All pancreata from the type 1 diabetic, autoantibody-positive and the nondiabetic donors were procured from brain-dead organ donors by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International POD, a program coordinated by the University of Florida (10). All procedures were in accordance with federal guidelines for organ donation and the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Case characteristics (Supplemental Table 1)

Pancreata were procured from 15 adult donors with type 1 diabetes (T1D), 17 autoantibody-positive (AA+) donors, and 17 nondiabetic (ND) donors matched for age (42.9 ± 5.6 vs 36.4 ± 3.5 vs 38.7 ± 4.4 y, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P = NS) (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B), sex (T1D group: 10 males, five females; AA+ group: 10 males, seven females; ND group: 11 males, six females), and body mass index (BMI; 24.4 ± 1.1 vs 25.3 ± 1.2 vs 25.8 ± 1.1 kg/m2, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P = NS) (Supplemental Figure 1, C and D).

Pancreas weight was decreased in the T1D donors and, to a lesser degree, in the AA+ donors, compared with the ND donors, in accord with previous observations (11) (38.1 ± 4.9 vs 73.8 ± 5.7 vs 90.5 ± 6.5 g, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND) (Supplemental Figure 1, E and F).

Pancreas acquisition and processing

nPOD uses a standardized preparation procedure for pancreata recovered from cadaveric organ donors (12). The pancreas is divided into three main regions (head, body, and tail), followed by serial transverse sections throughout the medial to lateral axis, allowing for the sampling of the entire pancreas organ while maintaining anatomical orientation. Because the preparation is completed within 2 hours, tissue integrity is maintained. Tissues intended for paraffin blocks are trimmed to pieces no larger than 1.5 × 1.5 cm and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 ± 8 hours. Fixation is terminated by transfer to 70% ethanol, and samples are subsequently processed and embedded in paraffin. Mounted transverse sections from the paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were obtained from the body of pancreas in most cases; in the instances in which blocks of pancreas body were unavailable, sections from the head of the pancreas were used.

In all the type 1 diabetic and autoantibody-positive donors and in most of the nondiabetic donors, the whole pancreas was weighed at the time of procurement. The pancreas from five nondiabetic organ donors was procured before the routine weighing of the pancreas was instituted.

Immunostaining

Assessment of presence and frequency of chromogranin-positive, hormone-negative (CPHN) cells

All staining was performed at the University of California, Los Angeles. Paraffin tissue sections from each subject were stained for chromogranin A, insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, and ghrelin. Standard immunohistochemistry protocol was used for fluorescent immunodetection of various proteins in the pancreatic sections (1). Briefly, slides were incubated at 4°C overnight with a cocktail of primary antibodies prepared in blocking solution (3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline and 0.2% Tween 20 [TBST]) at the following dilutions: rabbit anti chromogranin A (1:200, NB120–15160; Novus Biologicals); mouse antiglucagon (1:1000, G2654-.2ML; Sigma-Aldrich); guinea pig antiinsulin (1:200, 7842; Abcam), rat antisomatostatin (1:300, MAB354; EMD Millipore), goat antipancreatic polypeptide (1:3000; Everest Biotech), and rat antighrelin (1:50, MAB8200; R&D Systems). The primary antibodies were detected by a cocktail of appropriate secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) conjugated to Cy3 (1:200 for chromogranin A), fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:200 each, to detect glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, and ghrelin) or Cy5 (1:100, to detect insulin). Slides were counterstained to mark the nuclei using a mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vectashield; Vector Labs) and viewed using a Leica DM6000 microscope (Leica Microsystems), and images were acquired using the ×20 objective (×200 magnification) using a Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera (C4742-80-12AG; Indigo Scientific) and Openlab software (Improvision).

Assessment of endocrine hormones with endocrine transcription factors/replicating markers/islet inflammatory markers and chromogranin A

It is of great interest to know whether the CPHN cells are replicating and whether they express endocrine transcription factors or are surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate. To demonstrate this, we developed and used a new immunohistochemical staining technique. The new strategy involves monovalent F(ab′)2 fragments to distinguish between the two mouse primary antibodies. Here is a brief description of the protocol. After antigen retrieval of the paraffin sections of pancreas of nondiabetic or T1D cases (by following the standard antigen retrieval procedure using citrate buffer), tissues were then blocked with blocking buffer (3% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with the first primary antibodies prepared in antibody buffer (3% BSA in TBST) at the following dilutions (mouse anti Ki67 [1:50, M7240; DAKO], mouse anti-Nkx6.1 [1:300, F55A10; DSHB], mouse anti-Nkx2.2 [1:50, 74.5A5; DHSB]), mouse anti-CD45 [1:500, M0701; DAKO]) in separate sections at 4°C overnight. First, primary antibody was detected by Cy3-conjugated donkey antimouse IgG (1:100, 715-166-150; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Slides were then incubated sequentially with mouse serum (5% [vol/vol[, 015-000-120; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and unconjugated F(ab′)2 fragment of donkey antimouse IgG (40 μg/mL, 715-007-003; Jackson ImmonoResearch) for 1 hour at room temperature. After each incubation, the slides were washed with 1× TBST and 1× TBS (10 min each). After that, slides were incubated with second primary antibody (mouse antiglucagon, 1:2000, G2654-.2ML; Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. Second primary antibody was detected with donkey antimouse Alexa 647 (1:100, 715-606-151; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Finally, slides were incubated at 4°C overnight with a cocktail of third primary antibodies prepared at the following dilutions: guinea pig antiinsulin (1:100, 7842; Abcam), rat antisomatostatin (1:100, MAB354; EMD Millipore), goat antipancreatic polypeptide (1:3000; Everest Biotech), rat antighrelin (1:50, MAB8200, R&D Systems); and rabbit antichromogranin A (1:200, NB120-15160; Novus Biologicals). The third primary antibodies were detected by a cocktail of secondary antibodies [F(ab′)2 fragments]; donkey antiguinea pig Alexa 647 (1:100, 706-606-148, for insulin; Jackson ImmunoResearch), donkey antirat Alexa 647 (1:100, 712-606-153, for ghrelin and somatostatin; Jackson ImmunoResearch), donkey antigoat Alexa 647 (1:100, 705-606-147 for pancreatic polypeptide; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and donkey antirabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:100, 711-096-152 for chromogranin A; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Slides were counterstained to mark the nuclei using a mounting medium containing DAPI (Vectashield; Vector Labs) and viewed using a Leica DM6000 microscope (Leica Microsystems), and images were acquired using the ×20 objective (×200 magnification) using a Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera (C4742-80-12AG; Indigo Scientific) and Openlab software (Improvision).

Morphometric analysis

One section of the body of pancreas per subject was stained, except in five cases of the ND cohort (6012, 6015, 6017, 6021, and 6022) in which the pancreas body was unavailable; in these cases a section of the pancreas tail was stained. Fifty islets per subject were imaged at ×20 magnification. An islet was defined as a grouping of four or more endocrine cells. A cluster was defined as a grouping of three or fewer chromogranin-positive cells. Islets were selected by starting at the top left corner of the pancreatic tissue section and working across the tissue from left to right and back again in a serpentine fashion, imaging all islets in this systematic excursion across the tissue section. Analysis was performed in a blinded fashion (A.S.M., A.E.B., and C.S.), and all CPHN cells identified were confirmed by a second observer. The endocrine cells contained within each islet were manually counted and recorded as follows: 1) the number of cells staining for chromogranin A, 2) the number of cells staining for the endocrine hormone cocktail, and 3) the number of cells staining for insulin. Thus, cells staining for chromogranin A but not the other known pancreatic hormones (insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, or ghrelin) were noted.

At ×200 magnification, using the Leica DM6000 with a Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera and a 0.7x C-mount, each field of view was calculated to be 0.292 mm2. Within the fields imaged to obtain the 50 islets per subject, all single endocrine cells and clusters of endocrine cells (two or three adjacent endocrine cells) were counted and recorded as outlined above.

The mean number of endocrine cells counted within islets for the T1D group was 1719 ± 192 cells per donor, 2363 ± 247 cells per donor for the AA+ group, and 2380 ± 266 cells per donor for the ND group. The mean number of cells counted in clusters for the T1D group was 298 ± 32 cells per donor, 90 ± 7 cells per donor for the AA+ group, and 122 ± 16 cells per donor for the nondiabetic group. The mean number of CPHN cells counted in islets for the T1D group was 19.3 ± 4.1 cells per donor, 4.9 ± 0.9 cells per donor for the AA+ group, and 5.7 ± 2.3 per donor for the ND group was. The mean number of CPHN cells per individual identified in clusters for the T1D group was 58.1 ± 9.4 cells per donor, 8.2 ± 1.3 cells per donor for the AA+ group, and 11.4 ± 2.2 cells per donor for the ND group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test or ANOVA, where appropriate, with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software). Data in the graphs and tables are presented as means ± SEM. Findings were assumed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells are more frequent in T1D

Endocrine cells identified by immunoreactivity for chromogranin A but that did not express any known pancreatic islet hormone could be identified in islets and among scattered endocrine cells or as individual cells in the exocrine pancreas in T1D and ND controls (Figure 1). When quantified, these CPHN cells, although infrequent, were more abundant in the islets of donors with T1D compared with nondiabetic individuals (1.11% ± 0.20% vs 0.27% ± 0.10% of islet endocrine cells, T1D vs ND, P < .001) (Figure 2, A and B). CPHN cells were also more frequent in scattered endocrine cell clusters (18.99% ± 2.09% vs 7.42% ± 1.26% of all endocrine cells occurring in clusters, T1D vs ND, P < .0001) (Figure 2, C and D) and as single endocrine cells (21.27% ± 2.63% vs 8.90% ± 1.43% of all endocrine cells occurring as single cells, T1D vs ND, P < .001).

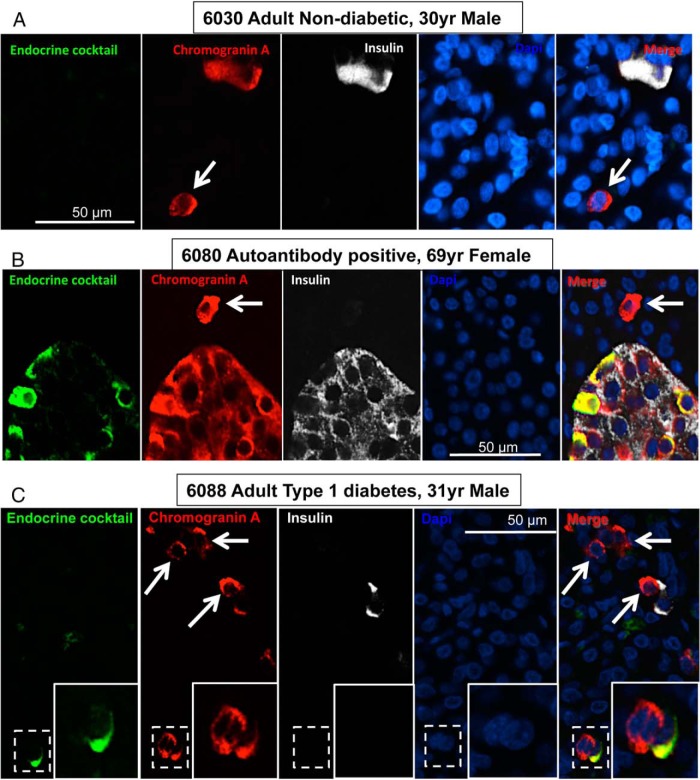

Figure 1.

Examples of CPHN cells in the pancreas from an adult ND donor (A), an adult AA+ donor (B), and adult T1D donor (C). Individual layers stained for an endocrine cocktail (glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, and ghrelin [green]), chromogranin A (red), insulin (white) and DAPI (blue) are shown along with the merged image. Arrows indicate CPHN cells. Scale bar, 50 μm.

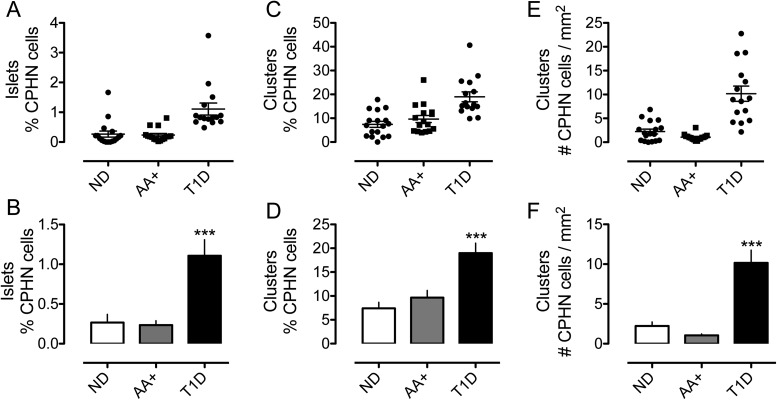

Figure 2.

The frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells was indeed increased in islets from donors with T1D (1.11% ± 0.20% vs 0.26% ± 0.06% vs 0.27% ± 0.10% of islet endocrine cells, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND) (A and B) and in scattered clusters of endocrine cells in the pancreas from T1D donors (18.99% ± 2.09% vs 9.67% ± 1.49% vs 7.42% ± 1.26% of scattered endocrine cells, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+, and T1D vs ND) (C and D). The frequency of scattered nonhormone expressing endocrine cells, expressed per unit area of the pancreas section, was increased in the pancreas sections from the donors with T1D (E and F) (10.17 ± 1.59 vs 1.06 ± 0.16 vs 2.23 ± 0.50 cells/mm2 pancreas, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND).

To determine whether the increase in CPHN cells precedes the onset of T1D, we also quantified their abundance in islet AA+ nondiabetic organ donors. In contrast, to established T1D, we found no increase in CPHN cells in the islet autoantibody group compared with the ND controls in islets (0.26% ± 0.06% vs 0.27% ± 0.10% of all islet endocrine cells, AA+ vs ND, P = NS) (Figure 2, A and B), scattered endocrine clusters (9.67% ± 1.49% vs 7.42% ± 1.26% of all endocrine cells occurring in clusters, AA+ vs ND, P = NS) (Figure 2, C and D) or individual cells (10.36% ± 1.65% vs. 8.90% ± 1.43% of all endocrine cells occurring as single cells, AA+ vs ND, P = NS).

The frequency of the scattered CPHN cells within endocrine cell clusters and present as single cells was also increased in T1D when expressed per unit area of pancreas but, again, were not increased in the pancreas from islet AA+ donors (clusters: 10.17 ± 1.59 vs 1.06 ± 0.16 vs 2.23 ± 0.50 cells/mm2 pancreas, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND; single cells: 7.91 ± 1.28 vs 0.78 ± 0.13 vs 1.88 ± 0.42 single cells/mm2 pancreas, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND) (Figure 2, E and F).

Potential contribution of nonhormone-expressing β-cells to the β-cell deficit in T1D

It has been reported that in nonobese autoimmune diabetes mice, approximately 50% of the apparent β-cell deficit may be due to the degranulation of β-cells, raising the question of whether the β-cell deficit in humans with T1D may be in part due to degranulation rather than loss of β-cells (5). The β-cell deficit per islet section in T1D in the present study was 95% (1.31 ± 0.72 vs 26.51 ± 3.03 β-cells/islet section, T1D vs ND, P < .0001). If all the CPHN cells/islet (0.40 ± 0.09 vs 0.11 ± 0.05 CPHN cells/islet, T1D vs ND, P < .005) were degranulated β-cells, then the β-cell deficit per islet would be reduced from 95% to 94% (Figure 3, A and B). Therefore, in contrast to the nonobese autoimmune diabetes mouse model, we conclude that β-cell degranulation does not contribute significantly to the evaluated β-cell loss in T1D in humans.

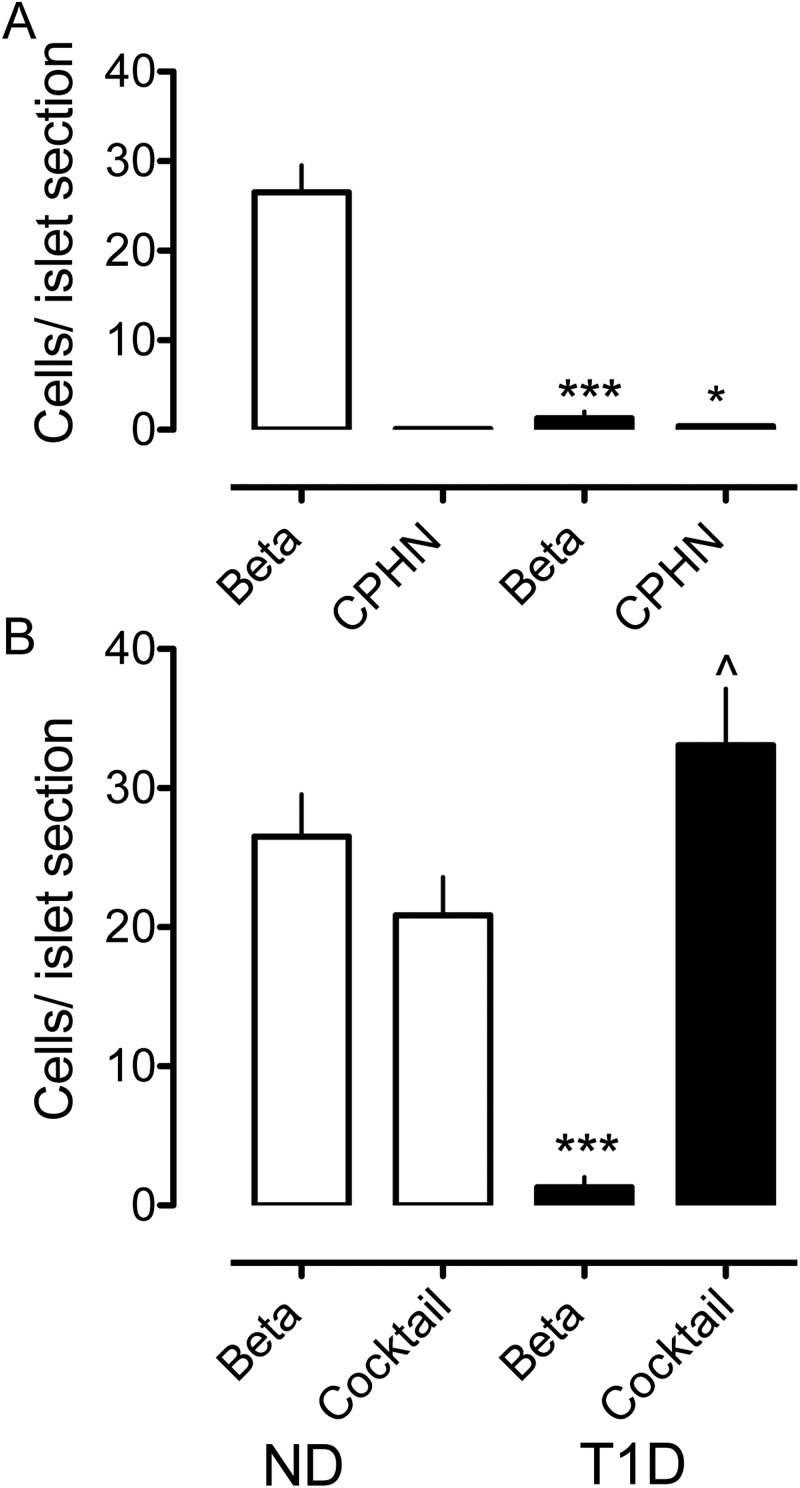

Figure 3.

The impact of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells on the deficit in β-cell mass in T1D is minimal. The number of cells per islet section of the CPHN cell fraction is very small when compared with the number of the β-cells per islet section in the ND, and the deficit in the β-cells in the T1D donors cannot be accounted for by the increase in the CPHN cells in T1D. A, There is an approximately 95% deficit in the β-cells in the islets from the subjects with T1D (1.31 ± 0.72 vs 26.51 ± 3.03 β-cells/islet, T1D vs ND, ***, P < .0001). The number of the CPHN cells per islet section is increased in T1D (0.40 ± 0.09 vs 0.11 ± 0.05 CPHN cells/islet section, T1D vs ND, , P < .005), but this increase does not account for the β-cell deficit seen in T1D. B, Islet endocrine cells expressing islet hormones other than insulin are increased in T1D (33.10 ± 4.06 vs 20.87 ± 2.74 endocrine cocktail cells/islet section, T1D vs ND, , P < .05). However, the β-cell deficit in T1D (1.31 ± 0.72 vs 26.51 ± 3.03 β-cells/islet section, T1D vs ND, ***, P < .0001) cannot be explained by the conversion of β-cells to other endocrine cells. White bars, ND donors; black bars, T1D donors.

Potential contribution of transdifferentiation of β-cells to other cell types in T1D

Recent interest has focused on the capacity for pancreatic endocrine cells to transdifferentiate to other endocrine cell types, and in the case of type 2 diabetes, this has been postulated as a mechanism of β-cell loss, whereas in T1D it has been postulated as a potential source of β-cells (13, 14). This has arisen from the apparent increase in α-cells per islet vs loss of β-cells per islet in type 2 diabetes. When examined in this manner, there is also an approximately 50% increase in other nonβ-endocrine cells per islet in T1D (33.0 ± 4.0 vs 20.87 ± 2.74 endocrine cocktail cells/islet, T1D vs ND, P < .05) (Figure 3B). As in type 2 diabetes, the β-cell deficit in T1D (1.31 ± 0.72 vs 26.51 ± 3.03 β-cells/islet, T1D vs ND, P < .0001) cannot be explained by conversion of β-cells to other endocrine cells. Moreover, the apparent increase in other non-β-endocrine cells per islet is likely an ascertainment bias because sections of residual islets (after near complete β-cell loss) would be expected to be relatively enriched in other endocrine cells.

The presence of detectable insulin-expressing cells in T1D does not predict the frequency of nonhormone expressing endocrine cells

In T1D, occasional insulin-expressing β-cells are commonly identified in small numbers, particularly as scattered cells in the exocrine pancreas (15, 16). Given the possibility that nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells may be precursors of newly forming β-cells, we hypothesized that scattered nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells would be more frequent in those individuals with detectable insulin-expressing β-cells. We identified insulin-expressing β-cells in 7 of the 15 individuals with T1D. Contrary to our hypothesis, the CPHN cells in islets were more frequently found in the T1D subjects in whom no residual insulin-positive cells were present (0.56 ± 0.14 vs. 0.21 ± 0.03 CPHN cells/islet, no residual insulin vs residual insulin, P < .05). There was no difference in the number of scattered CPHN cells between those T1D subjects in whom insulin-positive cells were still present in the pancreatic sections and those subjects in whom no residual insulin-positive cells were detected (10.31 ± 2.55 vs. 10.00 ± 1.97 CPHN cells in clusters/mm2 pancreas, no residual insulin vs residual insulin, P = NS) (Figure 4, A–D). In conclusion, the CPHN cells do not predict the presence or extent of β-cells in T1D.

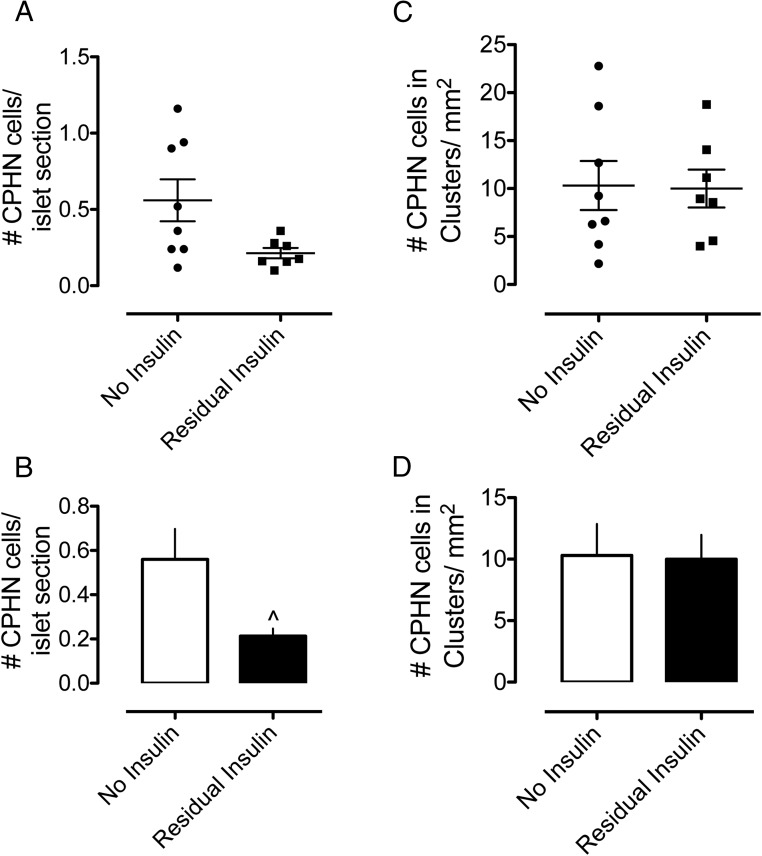

Figure 4.

Graphs comparing the number of CPHN cells in T1D subjects, grouped according to those in whom insulin-positive cells were still present in the pancreatic sections and those subjects in whom no residual insulin-positive cells were detected in the pancreas sections. A and B, The number of chromogranin A-positive cells per islet. The CPHN cells were identified more frequently in T1D subjects in whom no residual insulin-positive cells were present (0.56 ± 0.14 vs 0.21 ± 0.03 CPHN cells/islet section, no residual insulin vs residual insulin, P < .05). C and D, The number of CPHN cells found in the endocrine clusters per square millimeter of the pancreas. There was no difference in the number of CPHN cells between those T1D subjects in whom insulin-positive cells were still present in the pancreatic sections and those subjects in whom no residual insulin-positive cells were detected (10.31 ± 2.55 vs 10.00 ± 1.97 CPHN cells in clusters per square millimeter of pancreas, no residual insulin vs residual insulin, P = NS).

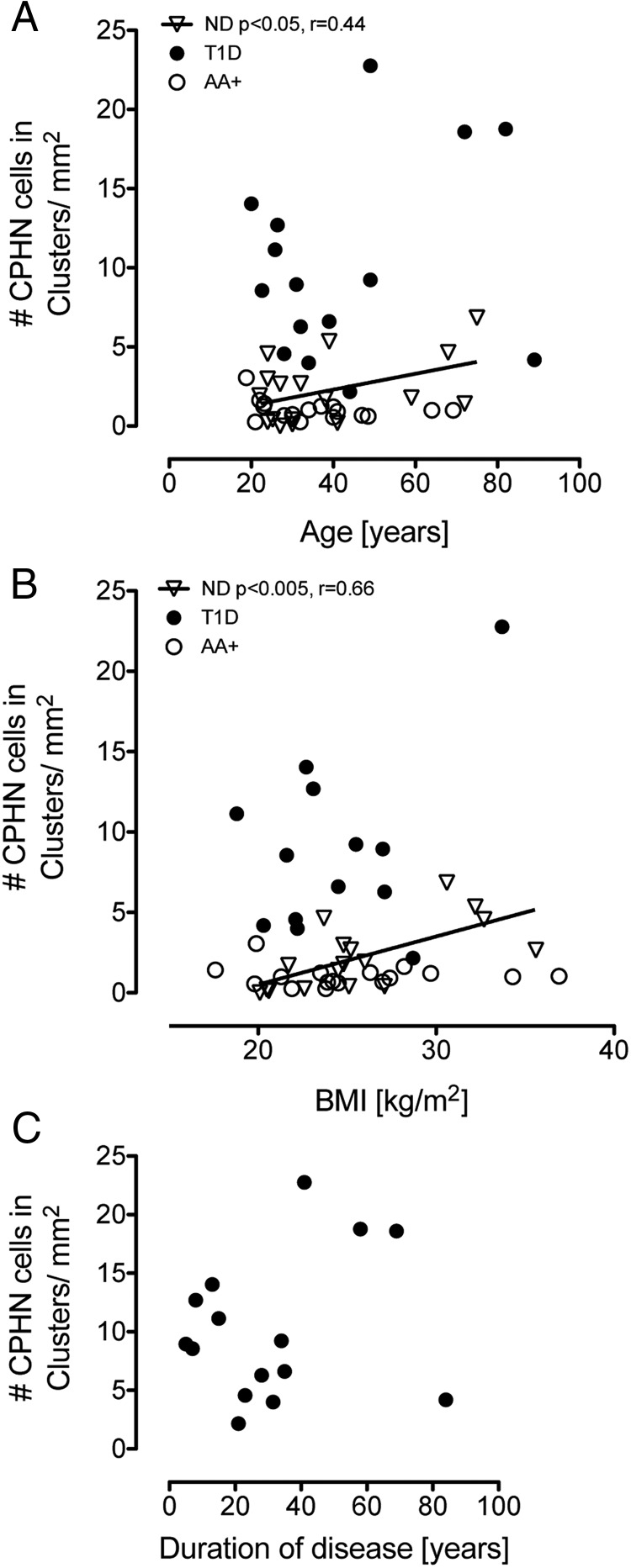

The relationship between age, BMI, and duration of diabetes on the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

The relationship of age, BMI, and duration of diabetes on the abundance of CPHN cells in the pancreas. There was a positive linear relationship between the frequency of the nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and both age (r = 0.44, P < .05) (A) and BMI (r = 0.66, P < .005) (B) in the ND donors. No relationship with age or BMI was present in either the T1D donors or the AA+ donors. There was no relationship with the duration of disease in the T1D donors (C).

To further investigate the potential origins of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells, we examined the relationship of age, BMI, and the duration of diabetes on the abundance of these cells. There was a positive linear relationship between the frequency of the nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and both age (r = 0.44, P < .05) (Figure 5A) and BMI (r = 0.66, P < .005) (Figure 5B) in the ND donors. No relationship with age or BMI was present in either the T1D donors or the AA+ donors. There was no relationship with duration of disease in the T1D donors (Figure 5C).

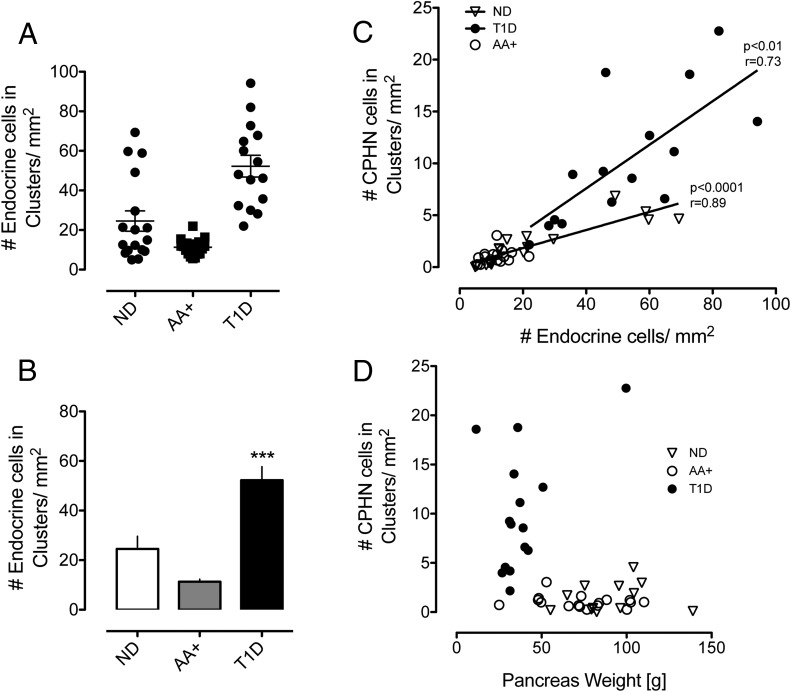

There are more scattered endocrine cells T1D

Having already established that there are more nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells scattered in the pancreas in T1D, we sought to establish whether this was true of all endocrine cells (the sum of all scattered chromagranin-positive cells per unit area of pancreas section, whether or not expressing hormones). There is indeed an increase in the total number of scattered endocrine cells in the pancreas in T1D (52.26 ± 5.47 vs 11.30 ± 1.04 vs 24.53 ± 5.13 cells/mm2, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND) (Figure 6, A and B). This raised the possibility that the apparent increase in hormone-negative endocrine cells in T1D might be simply a reflection of the decreased exocrine pancreas size in T1D.

Figure 6.

Endocrine cells occurring in scattered clusters were increased in the pancreas sections from donors with T1D (A and B) (52.26 ± 5.47 vs 11.30 ± 1.04 vs 24.53 ± 5.13 cells/mm2 pancreas, T1D vs AA+ vs ND, P < .0001, T1D vs AA+ and T1D vs ND). The relationship between the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and all endocrine cells per unit of pancreas area (C) is shown. Although there was a linear relationship between these parameters in both groups, the slope of the increase was greater in the T1D donors (r = 0.73, P < .01) than in ND controls (r = 0.89, P < .0001), implying an excess of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells independent of pancreas size. The relationship between the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and pancreatic weight in both groups (D) is shown. Although the pancreas weight in individuals with T1D was on average decreased compared with the ND and AA+ donors, the increase in the nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells in individuals with T1D was not related to the pancreas size.

To address this possibility, we examined the relationship between the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and all endocrine cells per unit of pancreas area (Figure 6C). Although there was a linear relationship between these parameters in both groups, the slope of the increase was greater in T1D (r = 0.73, P < .01) than in the ND controls (r = 0.89, P < .0001), implying an excess of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells independent of pancreas size. This impression was also corroborated by examining the relationship between the frequency of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells and pancreatic weight in both groups (Figure 6D). Whereas the pancreas weight in individuals with T1D was on average decreased compared with ND and AA+ donors, the increase in nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells in individuals with T1D was not related to pancreas size.

Characterization of replication in CPHN cells

Because CPHN cells were scattered in foci reminiscent of neonatal pancreas, we questioned whether these cells are replicating. To address this possibility, because of the number of antibodies required, we applied a newly developed immunohistochemical technique in pancreatic sections of T1D and ND (n = 4 each group) with anti-Ki67 and antiendocrine cocktail (containing antibodies against all the islet endocrine hormones and antichromogranin A). The four T1D cases were chosen as having the highest frequency of CPHN cells (6138, 6051, 6076, and 6050) and the ND cases matched as closely as possible for age and BMI (6015, 6021, 6029, and 6134). Although we again successfully identified increased CPHN cells in the T1D sections, none of these cells were positive for Ki67 (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B). We therefore conclude that the CPHN cells in T1D are not actively replicating.

CPHN cells have endocrine identity

In pancreatic sections from the same four T1D and four ND as above, we deployed the same novel immunohistochemistry approach to establish whether the CPHN cells conform to an islet endocrine lineage and, if so, a β-cell lineage by staining for Nkx6.1 (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B) and Nkx2.2 (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). Between 50 and 60 ×20 fields were imaged and analyzed in each section for each transcription factor. For Nkx2.2, CPHN cells were identified in both the T1D and ND pancreas sections and 100% of CPHN cells were also positive for Nkx2.2. For Nkx6.1, again CPHN cells were identified in both T1D and ND pancreas sections, and between 10% and 20% of CPHN were positive for Nkx6.1, with no difference between T1D and ND cases. The pancreatic CPHN cells are therefore confirmed to be of an islet lineage, and of these, approximately 10%–20% are of a β-cell lineage.

CPHN cells and inflammation

T1D is associated with an invasion of inflammatory cells in or around islets. We questioned whether CPHN cells are also targets of the inflammatory process. To address this possibility, we stained both ND and T1D pancreatic sections with anti-CD45, antiendocrine cocktail (that includes all the endocrine hormones), and antichromogranin A (Supplemental Figure 5, A and B). As expected, we identified a few CD45-positive cells in or around islets in the T1D cases (and more infrequently in ND islets), but in none of the cases were CPHN cells surrounded by CD45-positive cells. The same cases (four T1D, four ND) were used as for assessment of replication.

Discussion

We report that there is an increased frequency of endocrine cells that express no known islet hormone in T1D, both within islets and, more prominently, scattered in clusters and individually in the exocrine pancreas. There is also an increase in scattered endocrine cells that express known islet hormones in the exocrine pancreas in T1D. Although the abundance of these cells is insufficient to make a meaningful contribution to the loss of β-cell mass in T1D, their increased presence in this setting is comparable with that seen in humans with type 2 diabetes.

There has been recent interest in the concept that the apparent loss of β-cell mass and β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes may be due in part to either degranulation of β-cells and/or a change in endocrine cell identity to other islet endocrine cell types (4). It is not clear whether these changes precede diabetes and are important in the pathogenesis of diabetes or whether the changes are secondary to diabetes. Furthermore, it is unknown whether the nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells are due to a loss of identity or are newly forming endocrine cells. The pattern of distribution of endocrine cells that express no known hormones in type 2 diabetes shares some of the characteristics of the newly forming endocrine pancreas in late gestation and early infancy (6). The finding reported here that the abundance and pattern of distribution of these cells is comparable in types 1 and 2 diabetes has several implications.

First, the relatively high abundance of degranulated β-cells (∼50% of β-cells) reported in mouse models of types 1 and 2 diabetes far exceeds that in humans with types 1 or 2 diabetes (3%) (17, 18). Therefore, the proposal that β-cell loss in types 1 and type 2 diabetes may be in large part an artifact due to degranulation of β-cells may be valid in mice but is not the case for humans. Second, the fact that changes in β-cell identity (degranulation and mixed identity) have been reported in both types 1 and 2 diabetes suggests that these changes are secondary to diabetes rather than primary drivers of β-cell dysfunction (18, 19). In both types 1 and 2 diabetes, there are well-characterized and specific inducers of β-cell stress, cytokines delivered by autoreactive immune cells and misfolded islet amyloid polypeptide toxic oligomers, respectively (20, 21).

Stress pathways induced by both cytokines and misfolded protein toxic oligomers are known to both alter cell identity and to induce local regeneration programs (22, 23). Studies in other pathological contexts, such as the renal tubule, suggest that in response to acute injury, the tissue can dedifferentiate to permit the replication of viable cells toward regeneration while clearing out nonviable cells through apoptosis (24). Ideally, to establish the sequence of events leading to defective β-cell function and mass in diabetes, the pancreas from prediabetic individuals would be evaluated. We tried to approach this possibility by the use of the nPOD autoantibody positive nondiabetic pancreas repository. We did not identify any increase in hormone-negative endocrine cells in this group. However, most of these pancreases were secured from individuals that were autoreactive for only one autoantibody, and as such it is not surprising that they have no loss of β-cell mass (25) or identified islet inflammation because such individuals are unlikely to develop diabetes (26). If the pancreas from triple antibody-positive prediabetic individuals were to become available, this would be more relevant to the pattern of endocrine cell identity alteration in prediabetes.

We recently noted the similarity between the pattern of nonhormone-expressing endocrine cells in early human development and in pancreas of individuals with type 2 diabetes, implying that this might be due to attempted β-cell regeneration (6). That we see the same pattern in humans with T1D in whom there have been prior studies (7, 22, 27), suggesting ongoing attempted β-cell regeneration, lends further credence to this possibility. The origin of the putative new β-cells in adult human pancreas, for example, in T1D, remains to be resolved. Although the frequency of replication is very low in adult human β-cells, it has been reported to increase in the islets of new-onset T1D in association with an autoreactive-inflammatory infiltrate (22). However, it is of note that the CPHN cells evaluated here do not show increased replication. The cells scattered in the exocrine pancreas have been considered as derivatives of endocrine cell neogenesis previously (28), but this remains controversial, and its resolution is beyond the reach of investigation in the human pancreas in the absence of lineage tracing. Furthermore, although the CPHN cells are reported here as of islet lineage because they express Nkx2.2, and a subgroup are of potential β-cell lineage expressing Nkx6.1, given the single time point that is available from the human pancreas procured at death, it is impossible to know whether these cells are advancing toward a differentiated endocrine fate, dedifferentiating from a mature endocrine fate or static.

In summary, hormone-negative endocrine cells are present in the pancreas of individuals with type 1 diabetes at an increased frequency and with an abundance and distribution comparable with that observed in type 2 diabetes. The number of these cells is insufficient to explain β-cell loss in type 1 (or type 2) diabetes through putative degranulation. On the other hand, the distribution of these cells, being predominantly scattered in the exocrine pancreas, mimics that present in the developing human endocrine pancreas and is consistent with the possibility that there is ongoing attempted, albeit insufficient, β-cell regeneration in both forms of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the editorial assistance of Bonnie Lui from the Larry L. Hillblom Islet Research Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. This research was performed with the support of the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes, a collaborative type 1 diabetes research project sponsored by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International. Organ Procurement Organizations, partnering with the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes, to provide research resources are listed at www.jdrfnpod.org/our-partners.php.

Author contributions included the following: A.S.M.M., A.E.B., M.C., and C.S. performed the studies, undertook the microscopy, and performed the morphological analysis. A.S.M.M., A.E.B., S.D., and P.C.B. researched data, wrote the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript, edited the manuscript, and contributed to the discussion.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK077967 and Larry Hillblom Foundation Grant 2014-D-001-NET (to P.C.B.); and The Helmsley Charitable Trust and the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes through the Helmsley Charitable Trust George S. Eisenbarth Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes Award for Tetam Science Grant 2015PG-T1D052, Subaward 664215 (to A.E.B.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AA+

- autoantibody positive

- BMI

- body mass index

- CPHN

- chromogranin positive, hormone negative

- DAPI

- 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole

- ND

- nondiabetic

- nPOD

- Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes

- TBST

- Tris-buffered saline and 0.2% Tween 20

- T1D

- type 1 diabetes.

References

- 1. Kloppel G, Lohr M, Habich K, Oberholzer M, Heitz PU. Islet pathology and the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus revisited. Surv Synth Pathol Res. 1985;4:110–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atkinson MA, von Herrath M, Powers AC, Clare-Salzler M. Current concepts on the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes—considerations for attempts to prevent and reverse the disease. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:979–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cinti F, Bouchi R, Kim-Muller JY, et al. Evidence of β-cell dedifferentiation in human type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(3):1044–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Talchai C, Xuan S, Lin HV, Sussel L, Accili D. Pancreatic β cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic β cell failure. Cell. 2012;150:1223–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akirav E, Kushner JA, Herold KC. β-Cell mass and type 1 diabetes: going, going, gone? Diabetes. 2008;57:2883–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butler AE, Dhawan S, Hoang J, et al. β-Cell deficit in obese type 2 diabetes, a minor role of β-cell dedifferentiation and degranulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meier JJ, Bhushan A, Butler AE, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Sustained β cell apoptosis in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes: indirect evidence for islet regeneration? Diabetologia. 2005;48:2221–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonner-Weir S, Baxter LA, Schuppin GT, Smith FE. A second pathway for regeneration of adult exocrine and endocrine pancreas. A possible recapitulation of embryonic development. Diabetes. 1993;42:1715–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonner-Weir S, Li WC, Ouziel-Yahalom L, Guo L, Weir GC, Sharma A. β-Cell growth and regeneration: replication is only part of the story. Diabetes. 2010;59:2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell-Thompson M, Wasserfall C, Kaddis J, et al. Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes (nPOD): developing a tissue biobank for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28:608–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Campbell-Thompson M, Wasserfall C, Montgomery EL, Atkinson MA, Kaddis JS. Pancreas organ weight in individuals with disease-associated autoantibodies at risk for type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2012;308:2337–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell-Thompson ML, Montgomery EL, Foss RM, et al. Collection protocol for human pancreas. J Vis Exp. 2012;e4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thorel F, Nepote V, Avril I, et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic α-cells to β-cells after extreme β-cell loss. Nature. 2010;464:1149–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al-Hasani K, Pfeifer A, Courtney M, et al. Adult duct-lining cells can reprogram into β-like cells able to counter repeated cycles of toxin-induced diabetes. Dev Cell. 2013;26:86–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keenan HA, Sun JK, Levine J, et al. Residual insulin production and pancreatic ss-cell turnover after 50 years of diabetes: Joslin Medalist Study. Diabetes. 2010;59:2846–2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis AK, DuBose SN, Haller MJ, et al. Prevalence of detectable C-peptide according to age at diagnosis and duration of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Butler AE, Campbell-Thompson M, Gurlo T, Dawson DW, Atkinson M, Butler PC. Marked expansion of exocrine and endocrine pancreas with incretin therapy in humans with increased exocrine pancreas dysplasia and the potential for glucagon-producing neuroendocrine tumors. Diabetes. 2013;62:2595–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piran R, Lee SH, Li CR, Charbono A, Bradley LM, Levine F. Pharmacological induction of pancreatic islet cell transdifferentiation: relevance to type I diabetes. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spijker HS, Song H, Ellenbroek JH, et al. Loss of β-cell identity occurs in type 2 diabetes and is associated with islet amyloid deposits. Diabetes. 2015;64:2928–2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gurlo T, Ryazantsev S, Huang CJ, et al. Evidence for proteotoxicity in β cells in type 2 diabetes: toxic islet amyloid polypeptide oligomers form intracellularly in the secretory pathway. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:861–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petzold A, Solimena M, Knoch KP. Mechanisms of β cell dysfunction associated with viral infection. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willcox A, Richardson SJ, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. Evidence of increased islet cell proliferation in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2020–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costes S, Langen R, Gurlo T, Matveyenko AV, Butler PC. β-Cell failure in type 2 diabetes: a case of asking too much of too few? Diabetes. 2013;62:327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bonventre JV. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of surviving epithelial cells in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(suppl 1):S55–S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diedisheim M, Mallone R, Boitard C, Larger E. β-Cell mass in non-diabetic autoantibody-positive subjects: an analysis based on the nPOD database. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Batstra MR, Aanstoot HJ, Herbrink P. Prediction and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes using β-cell autoantibodies. Clin Lab. 2001;47:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meier JJ, Lin JC, Butler AE, Galasso R, Martinez DS, Butler PC. Direct evidence of attempted beta cell regeneration in an 89-year-old patient with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1838–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonner-Weir S, Inada A, Yatoh S, et al. Transdifferentiation of pancreatic ductal cells to endocrine β-cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]