Abstract

Context:

Unfavorable lipid levels contribute to cardiovascular disease and may also harm bone health.

Objective:

Our objective was to investigate relationships between fasting plasma lipid levels and incident fracture in midlife women undergoing the menopausal transition.

Design and Setting:

This was a 13-year prospective, longitudinal study of multiethnic women in five US communities, with near-annual assessments.

Participants:

At baseline, 2062 premenopausal or early perimenopausal women who had no history of fracture were included.

Exposures:

Fasting plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol at baseline and follow-up visits 1 and 3–7.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Incident nontraumatic fractures 1) 2 or more years after baseline, in relation to a single baseline level of lipids; and 2) 2–5 years later, in relation to time-varying lipid levels. Cox proportional hazards modelings estimated hazard ratios and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results:

Among the lipids, TG levels changed the most, with median levels increased by 16% during follow-up. An increase of 50 mg/dl in baseline TG level was associated with a 1.1-fold increased hazards of fracture (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04–1.18). Women with baseline TG higher than 300 mg/dl had an adjusted 2.5-fold greater hazards for fractures (95% CI, 1.13–5.44) than women with baseline TG lower than 150 mg/dl. Time-varying analyses showed a comparable TG level-fracture risk relationship. Associations between total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and fractures were not observed.

Conclusions:

Midlife women with high fasting plasma TG had an increased risk of incident nontraumatic fracture.

Secondary Abstract:

Midlife women with fasting plasma triglyceride (TG) of at least 300 mg/dl had 2.5-fold greater hazards of fracture in 2 years later and onward, compared to those with TG below 150 mg/dl, in a multiethnic cohort. Time-varying analyses revealed comparable results.

Midlife women with fasting plasma TG ≥ 300 mg/dL had 2.5-fold greater hazards of fracture in 2 years later and onward, compared to those with TG ≤150 mg/dL, in a multi-ethnic cohort. Time-varying analyses revealed comparable results.

Women have an estimated 40% risk of nontraumatic fracture after ages 50 years (1, 2). Diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), including peripheral arterial disease and abdominal aortic calcification, are associated with a 2- to 5-fold greater risk of incident hip fracture (2–6). Nontraumatic fractures and CVD share some risk factors, such as postmenopausal status, older age, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Unfavorable lipid profiles are major contributors to CVD and could influence bone health and fracture risk via multiple mechanisms, including oxidative stress, increased inflammation, reduced blood supply to bone, and alterations in bone remodeling (7, 8). Minimally oxidized lipids have been shown to inhibit bone-forming osteoblasts and stimulate bone-resorptive osteoclasts in mice (8). Bone marrow fat, which is triglyceride-rich (9), is an emerging risk factor for lower bone mineral density (BMD) in older women (10) and vertebral fracture (11); higher circulating triglyceride (TG) appears correlate with higher fat-to-water ratio in bone marrow (12).

Results from the few prospective epidemiological studies of the relationship between lipid levels and risk of nontraumatic fracture have been equivocal (13–16). In women, fasting plasma TG level typically increases before menopause (17). In contrast, increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), decreases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (17), and accelerated loss in BMD tend to emerge after the final menstrual period (18). We hypothesized that unfavorable fasting plasma lipid levels, particularly high TG, are associated with an increased risk of incident nontraumatic fractures in midlife women. We leveraged 13 years of data collected from women undergoing the menopausal transition in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN).

Materials and Methods

Study population

SWAN is a prospective, longitudinal community-based study of women's health as women undergo the menopausal transition. SWAN enrolled 3302 premenopausal or early menopausal multiethnic women, ages 42–52 years, at seven US sites between 1995 and 1997. Women were eligible if they did not use exogenous sex hormones, had at least one menstrual period in the past 3 months, had an intact uterus, had at least one intact ovary, and were not currently pregnant or lactating at the time of enrollment (19). All women provided written informed consent. At each near-annual follow-up visit, participants completed standardized questionnaires (administered by interviewers) about socioeconomic status, menstrual periods, exogenous hormone use, lifestyle factors, medical and surgical conditions, and use of medications and supplements.

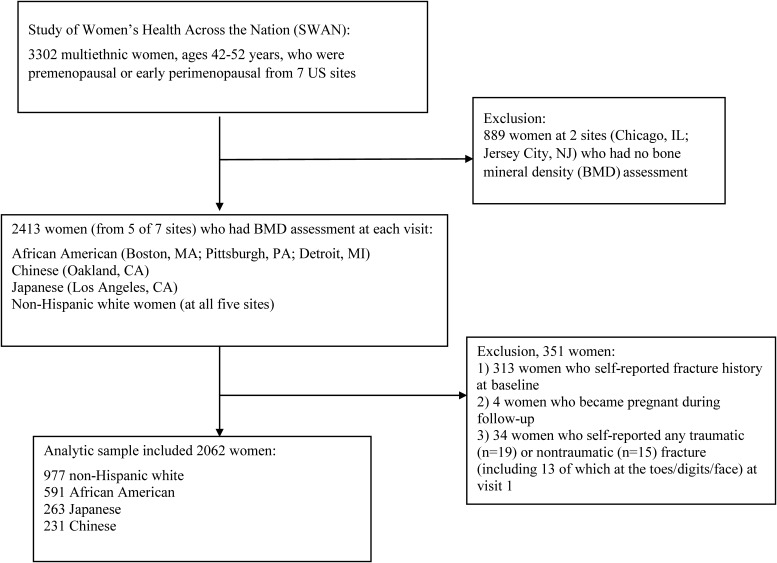

Women at five study sites (n = 2413) underwent BMD assessment by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at each visit. All five sites enrolled non-Hispanic white women and women of other races/ethnicities, including African-American (Boston, MA; Pittsburgh, PA; Detroit, MI), Chinese (Oakland, CA), and Japanese (Los Angeles, CA). The current study included 2062 women (Figure 1), after excluding 313 women who had a fracture history at baseline, four women who became pregnant during follow-up, and 34 women who self-reported any traumatic (n = 19) or nontraumatic (n = 15) fracture at visit 1 (to make sure baseline lipid measurements preceded fracture occurrence).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of 2062 women who were included in the current study from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation.

Assessment of incident nontraumatic fracture

We defined a woman as having an “incident fracture” when she self-reported her first nontraumatic fracture at any skeletal site, except the toe, digit, or face. At each follow-up visit, participants answered the questions: “Since your last study visit, how many times did you break or fracture a bone?”; “Which bones did you break or fracture”; and “Was it for any of the following reasons: after a fall from a height above the ground greater than 6 inches, in a motor vehicle accident, while moving fast (like running, bicycling or skating), while playing sports, or because something heavy fell on you or struck you?” Fractures that were not related to any of these reasons were considered to be nontraumatic fractures. Fractures at visits 2–6 were self-reported, and factures from visits 7–13 were confirmed by reviewing radiology reports in medical records. The false-positive rate of self-reported any fracture by SWAN participants was 4.6% (20).

Assessment of fasting lipid levels

Plasma levels of lipids (total cholesterol [TC], TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C) were measured in blood drawn after 12-hour fast, at baseline, and at visits 1 and 3–7. TC and TG were analyzed by standard enzymatic methods on Hitachi 747 analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics), and HDL-C was isolated using heparin-2M manganese chloride (17, 21). LDL-C level was calculated using Friedewald equation in women with fasting TG below 400 mg/dl (17, 21). Prespecified extreme values of TC were those outside the range 100–500 (mg/dl); TG, outside the range 20–2000 (mg/dl); HDL-C, outside the range 20–150 (mg/dl); and LDL-C, outside the range 25–400 (mg/dl). Lipid panels from each study site were measured centrally at Medical Research Laboratories International, Inc.

Assessment of pertinent characteristics

At all follow-up visits, weight (kilograms), height (meters), and blood pressure (BP) were measured. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2. BP was obtained from the right arm with participants seated with feet flat on the floor for at least 5 minutes before measurement. Self-reported current smoking status, alcohol use, family income, diabetes status, and hypertension status were assessed at each visit. Smoking status and alcohol use were assessed by questions: “Since your last study visit, have you smoked cigarettes regularly (at least one cigarette a day)?” and “Since your last study visit, did you drink any beer, wine, liquor, or mixed drinks?” Having diabetes was defined as having a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dl, self-reported diabetes, or use of insulin or other antidiabetes agent (22). Having hypertension was defined as having systolic BP of at least 140 mm Hg, diastolic BP of at least 90 mm Hg, self-reported hypertension, or use of any antihypertensive medication. Medication use at each visit included major bone-affecting agents (bisphosphonate, oral or inhaled corticosteroids, thiazide, calcitonin, recombinant parathyroid hormone, calcium supplements, and vitamin D supplements) and lipid-lowering medications (statins, fibric acid, niacin, and bile acid resins).

Menopausal stage incorporated self-reported menstrual cycle characteristics and exogenous hormone use at each visit (23). Premenopause was defined as menstruation in the past 3 months with menstrual regularity in the past year. Early perimenopause was defined as menstruation in the past 3 months with decreased regularity in the past year. Late perimenopause was defined as no menstruation for 3–11 months, and postmenopause was defined as no menstruation for 12 months. Menopausal stage at each visit was grouped by the SWAN Coordinating Center into the following stages: postmenopause by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hormone therapy (HT) user; postmenopause by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, non-HT user; natural postmenopause, non-HT user; natural postmenopause, HT user; early perimenopause; late perimenopause; premenopause; unknown because of HT use; and unknown because of hysterectomy.

BMD of the posteroanterior lumbar spine and total hip were measured using Hologic QDR 2000 densitometers (Pittsburgh and Oakland) and 4500A (Boston, Detroit area, and Los Angeles) (Hologic) (18, 23). Quality control procedures included daily phantom measurements and biannual cross-calibration with a circulating anthropomorphic spine standard. All scans were reviewed at the study site. Scans flagged with problems and a 5% random sample of scans were centrally reviewed by Synarc. Short-term in vivo BMD measurement variability was 0.014 g/cm2 (1.4%) for the lumbar spine and 0.016 g/cm2 (2.2%) for the femoral neck (23). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels were quantified using an ultrasensitive rate-immunonephelometric method (hsCRP on a BN 100, Dade-Behring) (24).

Recreational physical activity was derived from questionnaire data collected at baseline and visits 3, 5, and 6, and grouped into three clinical relevant levels (25): “not active” (0–1 time/month), “nonclinically significant” (2–3 times/month) and “clinically significant“ physical activity (≥4 times/month).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables (median, interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables (counts and percentages) were presented for the analytic sample overall and by four racial/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic white, African-American, Japanese, and Chinese; and were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis test (for continuous variables) and χ2 test (for categorical variables). For regression modeling, physical activity at visits 1, 4, and 7 was imputed using the last observation carried forward. TG levels had a skewed distribution and were natural log-transformed (26). Levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C showed normal distributions and were not log-transformed. Missing lipid values at visit 2 were excluded for regression.

Several Cox regression modeling approaches were used to investigate longitudinally the risk of incident fracture in relation to fasting lipid levels. First, we addressed the question: Is a lipid level at a single time-point (baseline) related to the risk of incident fracture between 2 and 13 years later? A woman contributed her follow-up time from baseline visit to the date of incident fracture, date of last follow-up, date of death, or visit 13, whichever occurred first. Women who self-reported any nontraumatic fracture within 2 years after baseline were excluded. Second, we used the available repeated measures of lipids through follow-up visit 7 to address the question: Is a lipid level of interest (time-varying) related to the risk of incident fracture that occurred 2–5 years later? We incorporated a 2-year lag in time-varying (repeated measures) analyses to 1) ensure that lipid levels preceded the fracture outcome (temporality) and 2) investigate whether results from time-varying (repeated measures) analyses corroborated those from Cox regression with a single baseline lipid level. Robust variance estimates were used to account for correlations between repeated measures (27). Using time-varying analyses with a 2-year lag, we also addressed the question: Is the mean lipid level from two consecutive measurements from baseline through visit 7, associated with the risk of incident fracture 2–5 years later?

For each approach, we examined continuous lipid levels (with or without natural log transformation) and categorical TG level (300+ mg/dl, 150–299 mg/dl, and <150 mg/dl as reference) to provide clinically informative results. TG level lower than 150 mg/dl is the clinically desirable concentration, and TG level greater than 150 mg/dl is one of five component criteria for metabolic syndrome. TG level of 300 mg/dl is a well-perceived, less-arguably high TG concentration. For each approach, model 1 adjusted for age, study site, and race/ethnicity; model 2 additionally included potential confounders: menopausal stage, current smoking (yes/no), alcohol use (yes/no), physical activity, diabetes (yes/no), and BMI. The “full” model added lumbar spine BMD to model 2 because BMD is a fracture risk factor in midlife women (20) and also could be a mediator for lipids-fracture associations. Covariates at baseline were used in models assessing the single baseline lipids. In time-varying analyses, these covariates were time-varying, where applicable. All models excluded lipid measurements that were known to be measured in nonfasting blood, had missing fasting information, or were extreme values. Proportionality assumption was tested by including product terms between follow-up time and covariates in multivariable models. No obvious violation was observed.

All analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). A two-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

More than 75% of the 2062 women at SWAN baseline were either non-Hispanic white (47%) or African-American (29%) (Table 1). The median age was 46 years (IQR, 44–48 years). Compared with Japanese and Chinese women, higher proportions of non-Hispanic white and African American women were aged 42–45 years, were early perimenopausal, had diabetes, and ever smoked. A higher fraction of African-American women used bone-affecting medications, particularly corticosteroids, compared with women of other races/ethnicities. The baseline median BMI, hip BMD, lumbar spine BMD, and hsCRP were highest in African-American women (all P values <.001). Overall, participants were mildly overweight at baseline, with a median BMI of 26 kg/m2 (ranging from 22 kg/m2 in Japanese and Chinese women to 30 kg/m2 in African-American women). Median BMD at the total hip and lumbar spine were within the nonosteopenic and nonosteoporotic range (by World Health Organization criteria (28)) in all racial/ethnic groups. The SWAN participants had favorable lipid profiles at baseline. Median TC was 192 mg/dl and median LDL-C was 114 mg/dl. Median TG was 89 mg/dl and 75% of women having a TG level of 128 mg/dl or lower. Median HDL-C level was 55 mg/dl (IQR, 47–66 mg/dl). Japanese and Chinese women had higher median TG and HDL-C levels and lower median LDL-C level than non-Hispanic white and African-American women.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristic and Fasting Lipid Levels of 2062 Women Without a History of Fracture at Baseline in SWAN

| Characteristics | Total (n = 2062) | Non-Hispanic White (n = 977) | African-American (n = 591) | Japanese (n = 263) | Chinese (n = 231) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age at baseline, y | .015 | |||||

| 42–45 | 880 (43) | 435 (45) | 267 (45) | 92 (35) | 86 (37) | |

| 46–49 | 897 (43) | 399 (41) | 252 (43) | 130 (49) | 116 (50) | |

| 50–52 | 285 (14) | 143 (15) | 72 (12) | 41 (16) | 29 (13) | |

| Menopausal stage | <.001 | |||||

| Premenopause | 1123 (55) | 517 (54) | 299 (51) | 163 (63) | 144 (63) | |

| Early perimenopause | 914 (45) | 446 (46) | 287 (49) | 97 (37) | 84 (37) | |

| Hypertensionb | 540 (26) | 200 (21) | 245 (42) | 50 (19) | 45 (19) | <.001 |

| Diabetesc | 92 (4) | 37 (4) | 53 (9) | 0 | 2 (1) | <.001 |

| Tobacco smoking | <.001 | |||||

| Current smoker | 330 (16) | 147 (15) | 146 (25) | 32 (12) | 5 (2) | |

| Past smoker | 519 (25) | 311 (32) | 140 (24) | 28 (11) | 3 (1) | |

| Never smoker | 1211 (59) | 519 (53) | 305 (51) | 201 (76) | 223 (97) | |

| Any alcohol drinks, yes | 983 (48) | 572 (59) | 251 (42) | 113 (43) | 47 (19) | <.001 |

| Physical activity, time/mo | <.001 | |||||

| 0–1 (not active) | 842 (41) | 336 (35) | 312 (53) | 87 (33) | 107 (48) | |

| 2–3 | 864 (42) | 414 (43) | 226 (39) | 131 (50) | 93 (41) | |

| ≥4 | 331 (16) | 216 (22) | 45 (8) | 45 (17) | 25 (11) | |

| Bone-affecting medicationsd | 164 (8) | 65 (7) | 83 (14) | 7 (3) | 9 (4) | <.001 |

| Lipid-lowering medicationse | 21 (1) | 11 (1) | 8 (1) | 2 (1) | 9 (4) | .131 |

| Calcium or vitamin D supplement | 34 (2) | 17 (2) | 12 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (0) | .315 |

| Characteristics | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26 (22–32) | 26 (23–31) | 30 (26–36) | 22 (20–25) | 22 (21–25) | <.001 |

| Weight, kg | 69 (58–85) | 71 (61–84) | 82 (69–98) | 55 (50–61) | 56 (51–63) | <.001 |

| hsCRP levels, mg/liter | 1.3 (0.5–4.2) | 1.4 (0.6–3.7) | 3.1 (1.0–7.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.6) | <.001 |

| BMD, g/cm2 | ||||||

| Total hip | 0.95 (0.86–1.06) | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 1.05 (0.95–1.14) | 0.88 (0.80–0.95) | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Lumbar spine | 1.08 (0.98–1.17) | 1.07 (0.98–1.15) | 1.14 (1.05–1.23) | 1.02 (0.94–1.09) | 1.04 (0.94–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Lipids, baseline, mg/dl | ||||||

| TC | 192 (171–215) | 192 (171–214) | 191 (168–217) | 196 (174–212) | 189 (171–208) | .626 |

| TG | 89 (66–128) | 89 (68–138) | 85 (63–121) | 94 (67–137) | 97 (68–128) | .018 |

| HDL-C | 55 (47–66) | 54 (46–64) | 53 (45–63) | 60 (51–69) | 60 (52–70) | <.001 |

| LDL-C | 114 (94–135) | 114 (95–135) | 117 (96–141) | 112 (91–130) | 105 (90–127) | <.001 |

P value: covariates distribution across racial/ethnic groups, using χ2 test (categorical variables) or Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous variables).

Hypertension: any use of antihypertensive medications, self-reported hypertension, or systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg.

Diabetes definition: fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl, self-reported diabetes, or any use of insulin or antidiabetes agent.

Bone-affecting medications: corticosteroids, thiazide, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or recombinant parathyroid hormone.

Lipid-lowering medications: statins, fibric acid, niacin, or bile acid resins.

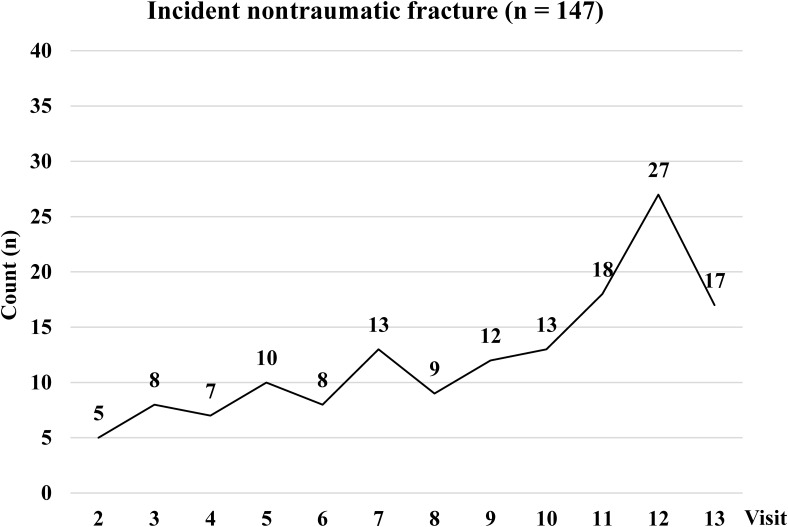

During follow-up, median TG levels increased the most, by 16% from baseline (89 mg/dl) to visit 7 (103 mg/dl), whereas median levels of TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C increased 7%, 7%, and 9%, respectively. The retention rate of SWAN participants ranged from 76% (visit 13) to 89% (visit 1). From visits 2 through 13, 147 had an incident (nontraumatic) fracture (Figure 2), which consisted of fractures of the foot (33%), ankle (16%), wrist (13%), ribs (12%), and legs (9%). At the time of incident fractures, 30% of women with incident fracture were perimenopausal or early postmenopausal, 55% were postmenopausal, and 15% had undetermined menopausal status because of HT and/or hysterectomy. Seventy-four percent (109 of 147) of women with incident fractures reported their fractures between visits 7 and 13, a period in which self-reported fractures were also confirmed by medical records review.

Figure 2.

Counts of incident nontraumatic fracture at each near-annual visit. All nontraumatic fractures excluded those at the face, toes, or digits. Incident nontraumatic fractures were self-reported fractures not related to a fall from a height above the ground greater than 6 inches, a motor vehicle accident, moving fast (like running, bicycling or skating), playing sports, or something heavy fell or struck. Between visits 7 and 13, self-reported fractures were further confirmed by medical records review: 74% of all (109 of 147) nontraumatic fractures were confirmed in medical records.

An increase of single baseline TG level by 50 mg/dl was associated with increased hazards of incident fractures (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.11, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04–1.18) after adjustment for smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, menopausal stage, diabetes, BMI, and lumbar spine BMD (“full model,” Table 2). No associations were observed between a single baseline level of natural log-transformed TG, TC, LDL-C or HDL-C, and incident fracture. In time-varying analyses (Table 3), every 50 mg/dl increase in TG at a given visit was associated with incident fracture 2–5 years later, with an adjusted HR of 1.07 (95% CI, 1.02–1.12, “full model”). For example, women with TG of 200 mg/dl at visit 3 had a 7% greater risk of nontraumatic fracture 2– 5 years later, compared to women with TG of 150 mg/dl at visit 3. One unit change in natural log-transformed TG (or 2.7-fold increase in TG level) at a given visit, the hazards of incident fracture between 2 and 5 years later was 1.31 (95% CI, 1.00–1.71, “model 2”); adjustment for lumbar spine BMD attenuated the association (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.97–1.70, “full model”).

Table 2.

HR Estimates of Incident Fracture Associated With a Single Baseline Level of Each Fasting Plasma Lipid

| Modelsa | HR (95% CI) for Incident Fractures 2 or More Y Later |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol (Per 50 mg/dl) | TG (Per 50 mg/dl) | ln(TG) (Per Unit Change)b | LDL-C (Per 50 mg/dl) | HDL-C (Per 10 mg/dl) | |

| Model 1: age, race/ethnicity, study site | 1.03 (0.78–1.36) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | 1.42 (0.95–2.13) | 0.87 (0.47–1.61) | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) |

| Model 2: model 1 + menopausal stage,c smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diabetes, BMI | 1.02 (0.78–1.35) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | 1.42 (0.97–2.10) | 0.90 (0.48–1.67) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) |

| Full model: model 2 + lumbar spine BMD | 1.02 (0.75–1.38) | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) | 1.30 (0.85–1.97) | 0.85 (0.43–1.68) | 0.99 (0.84–1.16) |

Abbreviation: ln(TG), natural log-transformed TG.

Full model included potential confounders in model 2 plus fracture risk factors and/or mediators. We did not log-transform levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C because they showed normal distribution.

1-unit change in ln(TG) represented 2.7-fold change in TG levels. For example, compared with a woman who had TG 100 mg/dl at baseline, a woman with TG 270 mg/dl at baseline had 1.3-fold greater hazards for fracture during follow-up.

All women were premenopausal or perimenopausal and had no exogenous hormone use at baseline.

Table 3.

HR Estimates of Incident Fracture Associated With Time-Varying Levels of Each Fasting Plasma Lipid

| Modelsb | HR (95% CI) for Incident Fractures Occurring 2–5 Y Latera |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (Per 50 mg/dl) | TG (Per 50 mg/dl) | ln(TG) (Per Unit Change)c | LDL-C (Per 50 mg/dl) | HDL-C (Per 10 mg/dl) | |

| Model 1: age, race/ethnicity, study site | 0.94 (0.79–1.11) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | 1.37 (1.06–1.76) | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) | 0.93 (0.85–1.02) |

| Model 2: model 1 + menopausal stage, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diabetes, BMId | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 1.06 (1.04–1.12) | 1.31 (1.00–1.71) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) |

| Full model: model 2 + lumbar spine BMD | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 1.28 (0.97–1.70) | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) |

Abbreviation: ln(TG), natural log-transformed TG.

Lipid level at a given visit i in relation to incident fracture risk between i + 2 and i + 5 y. Levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were not log-transformed because they showed normal distribution.

Model 2 and full model included time-varying covariates. Full model included potential confounders in model 2 and BMD (fracture risk factor and/or mediator).

1-unit change in ln(TG) represented 2.7-fold change in TG levels.

Time-varying menopausal stage (including exogenous HT use): postmenopause by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, non-HT user; postmenopause by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, HT user; natural postmenopause, non-HT user; natural postmenopause, HT user; early perimenopause; late perimenopause; premenopause; unknown because of HT use; and unknown because of hysterectomy.

Women with TG levels of at least 300 mg/dl, whether at baseline or in time-varying analyses, consistently had increased hazards of incident fracture. Women with baseline TG levels 300 mg/dl or higher had 2.5-fold greater hazards (full model: HR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.13–5.44) of fracture at visit 2 and onward, compared with women with baseline TG below 150 mg/dl (Table 4). In time-varying analyses, women with TG levels of at least 300 mg/dl still had 1.94-fold (95% CI, 1.14–3.30) increased hazards of incident fracture, compared with women with TG below 150 mg/dl. No association with fractures was observed for TG levels of 150–299 mg/dl. Mean TG level of at least 300 mg/dl for two consecutive follow-up visits was associated with fracture between 2 and 5 years later. Additional adjustment for TC and HDL-C in the full model did not change associations between categorical TG and incident fracture. In sensitivity analyses comparing women with TG of at least 208 mg/dl (upper 10%) vs women with TG below 208 mg/dl, adjusted HR for incident fracture was 1.90 (“full model:” 95% CI, 1.05–3.43).

Table 4.

Multivariable-Adjusted HR Estimates for Incident Fracture by Fasting Plasma TG Levels at Baseline and in Time-Varying Analyses

| TG level (mg/dl) | Number (%) of Repeat-Measures That Contributed to Fracture vs Nonfracture | Full Model HR (95% CI)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Fracture Incidence 2 or More Y Later, Based on Baseline Fasting TG Level | Time-Varying Analyses: TG Level at Visit i and Fracture Risk 2–5 Y Later |

|||

| Single TG Level | Mean TG Level of 2 Consecutive Measuresb | |||

| <150 | 793 (73)/7776 (77) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 150–299 | 242 (22)/2067 (20) | 0.89 (0.48–1.65) | 1.13 (0.80–1.59) | 1.03 (0.70–1.52) |

| ≥300 | 49 (5)/298 (3) | 2.48 (1.13–5.44) | 1.94 (1.14–3.30) | 2.21 (1.29–3.79) |

Full model included age at baseline, race/ethnicity, study site, smoking, drinking, physical activity, menopausal stage (including exogenous hormone use), BMI, diabetes, and lumbar spine BMD.

Mean TG level for TG at visit i and the last TG level measured before visit i in relation to fractures between i + 2 and i + 5 y.

Full models did not include sex hormone levels, saturated fat intake (calculated from food frequency questionnaire), hsCRP, hypertension, bone-affecting medications or supplements, lipid-lowering medications and total hip BMD. Fewer than 5% of participants used lipid-lowering medications. Total hip BMD was highly correlated with lumbar spine BMD (Pearson's r = 0.74, P < .0001) and did not alter results. Sex hormone levels, hsCRP, hypertension, and bone-affecting medications either were not associated with lipid levels or did not change the associations. TG levels were not related to saturated fat intake (r = 0.019 and 0.017, respectively) at baseline and visit 5 (where dietary intake data were available).

Discussion

Midlife women who had a fasting plasma TG levels of at least 300 mg/dl consistently had 2- to 2.5-fold increased hazards of nontraumatic fracture after adjusting for BMD and potential confounders. No associations were observed between other plasma lipids and fractures. Using three analytical approaches, higher TG levels were consistently associated with an increased risk of incident fracture. To our knowledge, this prospective, longitudinal, multiethnic cohort study was the first to assess time-varying lipid levels, obtained at multiple time-points across 7 years, in relation to incident nontraumatic fracture among midlife women undergoing the menopausal transition. Specifically, TG levels at a given time-point were associated with increased fracture risks 2–5 years later, after adjusting for the earliest TG values and time-varying menopausal status. This study raises the possibility that high fasting TG levels in midlife women may be an indicator for increased fracture risk.

Few prospective studies have examined lipid levels in relation to fracture risk (13–16) and findings in women were scarce. The Sweden Gothenburg Project studied men and women combined, ages 25–64 years (53% women, less than one-quarter of whom were postmenopausal) and reported positive associations between TC and fracture (16). Yet, associations in women specifically were not reported. The current study results are consistent with a post hoc report from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation trial (29). Postmenopausal women in the placebo group with high TG or low BMD at baseline had an increased risk of subsequent vertebral fracture, and raloxifene was more effective in reducing vertebral fracture in these women compared to women who had a normal TG or high BMD (29). Other prospective studies focused on men (14, 15) or examined nonfasting lipids (13), with inconsistent results.

TG may link CVD and nontraumatic fractures. Adults with diabetes (3) or CVD (4, 5) had a higher risk of nontraumatic fractures than those without. Women with diabetes often have elevated TG levels (30). Fracture risk was associated with high TG levels in midlife women in the current study, even after controlling for diabetes, BMD, and putative fracture risk factors. The underlying mechanisms for TG in association with fracture were unclear. We postulated that TG could influence nontraumatic fracture through its relationship with low-grade chronic inflammation that involves several pathways, including osteoprotegerin/receptor activator nuclear factor kb ligand (RANKL)/RANK in bone remodeling (31–33), IL-6 (34), and/or TNF soluble receptors (35). CRP, an acute phase biomarker of inflammation, did not alter the risk estimates when included in the models, but does not rule out a role for chronic inflammation.

Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a decoy soluble receptor that binds to RANKL, inhibits the effects of RANKL, and reduces bone resorption (36). Serum OPG concentrations were observed to be higher in postmenopausal women with diabetes than those without diabetes (37). Higher serum OPG levels were cross-sectionally related to lower nonfasting TG levels, greater HbA1C, and higher prevalence of diabetes (33). On the other hand, studies have reported lower TG levels in postmenopausal women with elevated levels of total soluble RANKL (32) and similar TG levels across OPG concentrations (31, 32). In addition, serum TG levels were positively related to circulating levels of IL-6 (34) and TNF receptors (35), which were inflammatory markers associated with increased hip fracture risks in postmenopausal women (38).

Women with vertebral fractures, compared with those without vertebral fractures, had a higher mean marrow fat (lipid-water ratio) (10), of which the majority is composed of TG (9). Circulating TG specifically may in part explain the variability in bone marrow lipid-water ratio (12). It is plausible that circulating TG levels are associated with fracture at least in part because it is an indicator of greater bone marrow fat content.

The current study observed consistently increased fracture risks based on a single baseline TG level and separately, repeat measures of TG. This consistency may be due to the modest variability in fasting TG levels across the follow-up visits. The distributions of lipid levels in the SWAN participants suggest a relatively health cohort regarding lipids, and less than 10% of women had TG levels greater than 300 mg/dl. Sensitivity analyses using the 90th percentile (208 mg/dl) as cut-point for TG suggested associations similar to those in original analyses. We acknowledge the possibility of a chance finding due to the small numbers of women with a TG higher than 300 mg/dl and advocate for more studies. Underlying mechanisms remain to be clarified for nontraumatic fracture in midlife women. Any nontraumatic fracture occurred during the menopausal transition is a risk factor for another fracture (39). Our results may not be generalizable to other populations, such as older postmenopausal women or men. Although self-reported fractures from visits 2 through 6 (about 26% of all incident fractures) were not confirmed by medical records review, the rate of false-positive finding of any fracture was low: 5% (9 of 193) of all self-reported fractures were incorrect in medical records (20). The bias from inaccurate years of follow-up (for women who self-reported fracture at visits 2–6), measurement errors for lipids, or false-positive self-reported fractures were likely small and nondifferential.

In conclusion, midlife women with high fasting plasma TG (300 mg/dl or more) had about a 2- to 2.5-fold increased risk of nontraumatic fractures, after controlling for BMD, diabetes, BMI, menopausal status, and other potential confounders. Further investigation of the roles of TG in bone remodeling, BMD, and the risk of fracture in midlife women are warranted. If the current results are confirmed, high fasting plasma TG could be a modifiable risk factor and help to identify midlife women at risk of nontraumatic fracture.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend our deepest appreciation to the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN).

The SWAN has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, and U01AG012495). This publication was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, through the University of California San Francisco-Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Grant UL1 RR024131). Supplemental funding from the National Institute on Aging (Project Number: 7R21AG040568) is gratefully acknowledged. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH, or the NIH.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Siobán Harlow (principal investigator [PI] 2011–present), MaryFran Sowers (PI 1994–2011); Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA: Joel Finkelstein (PI 1999–present), Robert Neer (PI 1994–1999); Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL: Howard Kravitz (PI 2009–present); Lynda Powell (PI 1994–2009); University of California, Davis/Kaiser: Ellen Gold (PI); University of California, Los Angeles: Gail Greendale (PI); Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY: Carol Derby (PI 2011–present), Rachel Wildman (PI 2010–2011); Nanette Santoro (PI 2004–2010); University of Medicine and Dentistry, New Jersey Medical School, Newark: Gerson Weiss (PI 1994–2004); and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Karen Matthews (PI).

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD: Winifred Rossi (2012–present); Sherry Sherman (1994–2012); Marcia Ory (1994–2001); National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD: Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Maria Mori Brooks (PI 2012–present); Kim Sutton-Tyrrell (PI 2001–2012); New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA: Sonja McKinlay (PI 1995–2001).

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair.

Disclosure Summary: All authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- BMI

- body mass index

- BP

- blood pressure

- CI

- confidence interval

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- HDL-C

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

- hazard ratio

- hsCRP

- high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- HT

- hormone therapy

- IQR

- interquartile range

- LDL-C

- low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- OPG

- osteoprotegerin

- RANK

- nuclear factor κB

- RANKL

- nuclear factor κB ligand

- SWAN

- Study of Women's Health Across the Nation

- TC

- total cholesterol

- TG

- triglyceride.

References

- 1. Melton LJ, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C, Lane AW, Riggs BL. How many women have osteoporosis? J Bone Mineral Res. 2005;20:886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cauley JA, Wu L, Wampler NS, et al. Clinical risk factors for fractures in multi-ethnic women: the Women's Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1816–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heath H, 3rd, Melton LJ, 3rd, Chu CP. Diabetes mellitus and risk of skeletal fracture. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kanis J, Oden A, Johnell O. Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sennerby U, Melhus H, Gedeborg R, et al. Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2009;302:1666–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Szulc P, Kiel DP, Delmas PD. Calcifications in the abdominal aorta predict fractures in men: MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farhat GN, Cauley JA. The link between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2008;5:19–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tintut Y, Demer LL. Effects of bioactive lipids and lipoproteins on bone. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fazeli PK, Horowitz MC, MacDougald OA, et al. Marrow fat and bone—new perspectives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwartz AV, Sigurdsson S, Hue TF, et al. Vertebral bone marrow fat associated with lower trabecular BMD and prevalent vertebral fracture in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2294–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patsch JM, Li X, Baum T, et al. Bone marrow fat composition as a novel imaging biomarker in postmenopausal women with prevalent fragility fractures. J Bone Mineral Res. 2013;28:1721–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bredella MA, Gill CM, Gerweck AV, et al. Ectopic and serum lipid levels are positively associated with bone marrow fat in obesity. Radiology. 2013;269:534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahmed LA, Schirmer H, Berntsen GK, Fonnebo V, Joakimsen RM. Features of the metabolic syndrome and the risk of non-vertebral fractures: the Tromso study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SH, Baek S, Ahn SH, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and incident fractures in Korean men: a 3-year follow-up observational study using national health insurance claims data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1615–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Szulc P, Varennes A, Delmas PD, Goudable J, Chapurlat R. Men with metabolic syndrome have lower bone mineral density but lower fracture risk–the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1446–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trimpou P, Oden A, Simonsson T, Wilhelmsen L, Landin-Wilhelmsen K. High serum total cholesterol is a long-term cause of osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1615–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, et al. Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopausal transition? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2366–2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greendale GA, Sowers M, Han W, et al. Bone mineral density loss in relation to the final menstrual period in a multiethnic cohort: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sowers M, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: a multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Marcus R, Kelsey J, eds. Menopause. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cauley JA, Greendale GA, Ruppert K, et al. Serum 25 hydroxyvitamin d, bone mineral density and fracture risk across the menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2046–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Derby CA, Crawford SL, Pasternak RC, Sowers M, Sternfeld B, Matthews KA. Lipid changes during the menopause transition in relation to age and weight: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1352–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khalil N, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Strotmeyer ES, et al. Menopausal bone changes and incident fractures in diabetic women: a cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1367–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Finkelstein JS, Brockwell SE, Mehta V, et al. Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:861–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman RP, Matthews KA, et al. Sex hormone–binding globulin and the free androgen index are related to cardiovascular risk factors in multiethnic premenopausal and perimenopausal women enrolled in the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN). Circulation. 2005;111:1242–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dugan SA, Bromberger JT, Segawa E, Avery E, Sternfeld B. Association between physical activity and depressive symptoms: midlife women in SWAN. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin DY, Wei L-J. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton Iii LJ, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Black DM, et al. Associations between baseline risk factors and vertebral fracture Risk in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Study. J Bone Mineral Res. 2004;19:764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walden CE, Knopp RH, Wahl PW, Beach KW, Strandness E. Sex differences in the effect of diabetes mellitus on lipoprotein triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh ES, Rhee EJ, OH KW, et al. Circulating osteoprotegerin levels are associated with age, waist-to-hip ratio, serum total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy Korean women. Metabolism. 2005;54:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poornima IG, Mackey RH, Buhari AM, Cauley JA, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Relationship between circulating serum osteoprotegerin and total receptor activator of nuclear kappa-B ligand levels, triglycerides, and coronary calcification in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2014;21:702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vik A, Mathiesen EB, Brox J, et al. Serum osteoprotegerin is a predictor for incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in a general population: the Tromso Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fernández-Real J-M, Broch M, Richart JVC, Ricart W. Interleukin-6 gene polymorphism and lipid abnormalities in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1334–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Svenungsson E, Gunnarsson I, Fei G-Z, Lundberg IE, Klareskog L, Frostegård J. Elevated triglycerides and low levels of high-density lipoprotein as markers of disease activity in association with up-regulation of the tumor necrosis factor α/tumor necrosis factor receptor system in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2533–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hofbauer LC, Schoppet M. CLinical implications of the osteoprotegerin/RANKL/RANK system for bone and vascular diseases. JAMA. 2004;292:490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Browner WS, Lui LY, Cummings SR. Associations of serum osteoprotegerin levels with diabetes, stroke, bone density, fractures, and mortality in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barbour KE, Boudreau R, Danielson ME, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of hip fracture: the Women's Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1167–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Mineral Res. 2000;15:721–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]