Abstract

For more than three decades healthcare decentralization has been promoted in developing countries as a way of improving the financing and delivery of public healthcare. Decision autonomy under healthcare decentralization would determine the role and scope of responsibility of local authorities. Jalal Mohammed, Nicola North, and Toni Ashton analyze decision autonomy within decentralized services in Fiji. They conclude that the narrow decision space allowed to local entities might have limited the benefits of decentralization on users and providers. To discuss the costs and benefits of healthcare decentralization this paper uses the U-form and M-form typology to further illustrate the role of decision autonomy under healthcare decentralization. This paper argues that when evaluating healthcare decentralization, it is important to determine whether the benefits from decentralization are greater than its costs. The U-form and M-form framework is proposed as a useful typology to evaluate different types of institutional arrangements under healthcare decentralization. Under this model, the more decentralized organizational form (M-form) is superior if the benefits from flexibility exceed the costs of duplication and the more centralized organizational form (U-form) is superior if the savings from economies of scale outweigh the costly decision-making process from the center to the regions. Budgetary and financial autonomy and effective mechanisms to maintain local governments accountable for their spending behavior are key decision autonomy variables that could sway the cost-benefit analysis of healthcare decentralization.

Keywords: Health Decentralization, Organizational Form, Health Reform, Decision Autonomy

Introduction

Healthcare reform is currently one of the main priorities of governments around the world, as developing and developed countries experience population aging and raising healthcare costs. Since the 1980s, healthcare decentralization has been a popular tool of healthcare reforms. Healthcare decentralization has usually been portrayed as a way of increasing efficiency on healthcare financing and delivery. The flexibility of decentralized health services is perceived as superior to the rigidities and failures of ‘Stalinist’ centralized planning, since local knowledge can be used to address local needs and tastes.1 From a theoretical perspective, decentralized health services have additional advantages. They are less exposed to the political and budgetary considerations that affect central policy-making if decentralized governments have full decision-making autonomy and effective revenue collection mechanisms.2 Underrepresented regions or populations overlooked by central governments might be better off once the administration of health services is devolved to local communities.

Advocates of decentralization argue that market failures in the health sector and regional disparities, which could justify healthcare centralization in the first place, can be addressed in decentralized institutional frameworks. These models should contain the right incentives, resource transfers and better coordination across different government levels.3 In practice, it is politically sensitive and time consuming to set these systems in place. Thus, it is still an open question whether providing basic health services in developing countries is better under a decentralized system. Jalal Mohammed, Nicola North, and Toni Ashton investigate the role of decision space within decentralized services using Fiji as a case study.4 Their contribution shows how decision space can be systematically assessed to better characterize healthcare decentralization efforts. They argue that decentralization can occur along different domains and the specific decision-making arrangements between central and local authorities might explain the success or failure of healthcare decentralization.

In general, the academic literature has ambivalent conclusions about the outcome of healthcare decentralization.5-7 Several contributions argue that decentralization neither increased local government healthcare finances, nor improved equity, quality or efficiency of publicly run health services.5,8 In many cases it had the opposite effect, as performance deteriorated due to financial constraints, poor managerial skills at the local level, and supply failures.6 However, studies acknowledge some positive effects mainly in areas where community participation became more active and in some regions that traditionally devoted more resources to healthcare and were eager to get local autonomy to administer these resources better.9

One methodological challenge in the healthcare decentralization literature is its failure to isolate the effect of decentralization from the overall consequences of economic adjustment. Several decentralization experiments occurred in periods of deep economic crisis.5,8 Consequently, most empirical studies overestimate the negative impacts of decentralization policies and cannot disentangle the impact of decentralization by itself. Very few studies have been able to use natural experiments to isolate the impact of economic adjustment from healthcare decentralization.10,11 Recent decentralization efforts have been implemented in more stable political and economic environments. The study by Mohammed, North, and Ashton uses an interesting case study where an initial decentralization effort was pushed back for different external factors. One year later, a different devolution process was implemented. By contrast with the first decentralization effort, less decision authority was devolved to the local entities in the second period. Future research should take advantage of this potential source of exogenous change in health policy to measure the impact of each type of decentralization model on access to care and health outcomes.

A source of confusion in the healthcare decentralization literature is the lack of specificity on the conceptual definition of healthcare decentralization. Deconcentration, delegation, devolution, and privatization are administrative changes that are commonly mislabeled as healthcare decentralization by academics and policy-makers.12 Deconcentration is a shift on responsibility from the center to the periphery within an organization structure, delegation and devolution reallocates authority in separate government entities or sub-national governments. Privatization transfers ownership and sometimes responsibility to private agents. The study by Mohammed, North, and Ashton argues that the first decentralization period in Fiji could fit better its traditional definition. By contrast, the more recent devolution arrangement could be better characterized as deconcentration, since decision autonomy on finances, service organization, human resources, access rules, and governance remained highly centralized. Under the new arrangement, local authorities lacked the autonomy required to operate differently from other regions because the central government controlled the main sources of funding and determined allocation rules.

M-Form vs. U-Form and Decision Autonomy After Healthcare Decentralization

The authors argue that the current administrative arrangement in Fiji might not be taking advantage of healthcare decentralization since local authorities lacked decision autonomy. The theory of organizations can be useful to better understand decision autonomy under healthcare decentralization arrangements. The M-form (multidivisional form) and U-form (unitary form) are two categories widely applied in industrial organization.13,14 This typology has been used to contrast different types of government arrangements and institutional frameworks in the comparative economics literature.15 While the U-form resembles a highly centralized administrative structure, the M-form fits the description of a decentralized arrangement.1

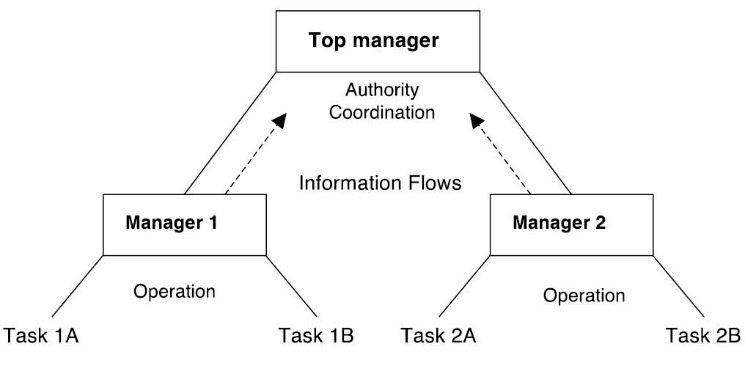

This framework can be applied to better understand the diversity of healthcare decentralization reforms. For example, it can be used to compare decision autonomy under different models of healthcare decentralization. In the U-form system, the central government has the authority and responsibility of delivering healthcare (Figure 1). A top manager coordinates its provision through intermediate managers who are solely responsible for operating public healthcare facilities. In Figure 1, Manager 1 is in charge of a specialized public service, say distribute prescription drugs, in two regions (A and B). Similarly, Manager 2 is responsible of another public service, for example prescribing drugs, in the same two regions (A and B).

Figure 1.

U-Form Organization of a Centralized Public Service.

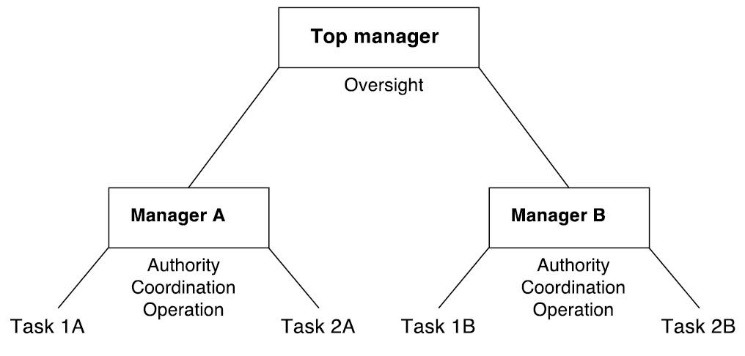

In the M-form, the central entity devolves the decision-making authority and responsibility for providing a public service to regional or local managers (Figure 2). As they are closer to their constituencies, these administrative units are also accountable for operating the two health services, distribute and prescribe pharmaceuticals. In contrast with the U-Form, in Figure 2 Manager 1 is in charge of both activities, distributing and prescribing drugs, in one region (A) only. Similarly, Manager 2 is responsible for the two activities in the second region (B). The central government keeps some oversight functions to insure that all citizens receive similar bundles of public services across regions. Central managers can pursue this goal by evaluating regional performance and assisting under-performers. In addition, they can encourage regional managers to cooperate in areas where they could take advantage of some economies of scale, for example, in bidding for better pharmaceutical prices with suppliers.

Figure 2.

M-Form Organization of a Centralized Public Service.

Various theoretical assessments on the cost and benefits of U-Form and M-Form organizations show a trade-off between these models.1,15 The M-form benefits from better use of local information, but forgoes economies of scale that give the U-form lower operation costs. The costly duplication of health services (1, 2) in each region (A, B) of the M-form model does not exist in the U-form model, as each manager specializes in one public service for the two regions. The decentralized organization, however, has an advantage in flexibility. As they are closer to their constituency, intermediate managers in the M-form are able to respond rapidly to shifts on local demand. From the perspective of the central manager, it is also possible to experiment with different provision models across regions.

Managers 1 and 2 in the U-form lack decision autonomy, since it is mostly centralized. The decision-making process from the center to the regions can be slow and inefficient, as circumstances change fast. Thus, the M-form is superior if the benefits from flexibility exceed the costs of duplication. The U-form is better if the savings from economies of scale outweigh the costly process of information transmittal to/from the center.1 In this cost-benefit analysis, decision space is endogenous to the model. Under the M-form administrative structure, local governments have full budgetary and financial autonomy, including revenue collection autonomy. The role of the central manager is minimal, limiting its oversight to measuring performance and promoting cooperation. Local governments with the administrative capacity to mobilize local resources effectively would benefit the most from decentralization. By contrast, impoverished regions with limited resources or low capacity to mobilize them effectively would benefit the least from more decision autonomy.

Under the U-form administrative structure, the central government has full budgetary and decision autonomy, and it is the single revenue collection entity. In this arrangement, the role of the local manager is minimal, limiting its actions to implementing policies and programs decided at the center, using resources that are also transferred from the center even if a share of those resources were collected locally. In fact, this costly and inefficient process of information and resource transfer is a key element that would sway the cost-benefit analysis of healthcare centralization. Central governments with administrative capacity to respond rapidly to changing local circumstances are more likely to benefit from healthcare centralization. By contrast, inflexible central government responses that clash with heterogeneous and rapidly changing regional realities would benefit the least from centralizing decision-making.

In reality, recent healthcare decentralization efforts combine features from both organizational forms. Institutional arrangements after healthcare decentralization often times create shared decision space arrangements between local and central authorities. Budgetary and financial autonomy and effective mechanisms to maintain local governments accountable are key decision autonomy variables that would determine whether shared decision arrangements are effective after healthcare decentralization.

Since the early 2000s Fiji has transition from a U-form to an M-form administrative structure even though decision autonomy remains centralized in its current organizational form. The study by Mohammed, North, and Ashton concludes that the narrow decision space allowed to decentralized entities on the recent healthcare deconcentration in Fiji might limit the benefits of decentralization for users and providers. According to the proposed U-Form vs. M-Form model the advantage of centralized decision autonomy (eg, reduce regional disparities, economies of scale) should outweigh the advantages of flexibility and local knowledge in order to be efficient. An empirical assessment of the two types of decentralization models implemented in Fiji would be useful to better assess the costs and benefits of decentralization.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contribution

AVB is the single author of the paper.

Citation: Bustamante AV. U-form vs. M-form: how to understand decision autonomy under healthcare decentralization? Comment on "Decentralisation of health services in Fiji: a decision space analysis." Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(9):561–563. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.73

References

- 1.Qian YY, Roland G, Xu CG. Coordination and experimentation in M-form and U-form organizations. J Polit Econ. 2006;114(2):366–402. doi: 10.1086/501170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BC. The decentralization of health care in developing countries: organizational options. Public Adm Deve. 1997;17(4):399–412. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossert T. Analyzing the decentralization of health systems in developing countries: Decision space, innovation and performance. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(10):1513–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammed J, North N, Ashton T. Decentralisation of health services in Fiji: a decision space analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(3):173–181. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prudhomme R. The dangers of decentralization. World Bank Res Obs. 1995;10(2):201–220. doi: 10.1093/wbro/10.2.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birn AE. Federalist flirtations: The politics and execution of health services decentralization for the uninsured population in Mexico, 1985-1995. J Public Health Policy. 1999;20(1):81–108. doi: 10.2307/3343260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins P. Special issue - Decentralisation and local governance in Africa. Public Adm Dev. 2003;23(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/pad.266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homedes N, Ugalde A. Why neoliberal health reforms have failed in Latin America. Health Policy. 2005;71(1):83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaneda T, Beeharry G, Griffin C. Decentralization of health services in Latin American countries: Issues and some lessons. Annual World Bank Conference on Development in Latin America and the Caribbean 1999, Proceedings. 2000:249–269. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargas Bustamante A. The tradeoff between centralized and decentralized health services: evidence from rural areas in Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5):925–934. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bustamante AV. Comparing federal and state healthcare provider performance in villages targeted by the conditional cash transfer programme of Mexico. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(10):1251–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rondinelli DA. Government decentralization and economic development: the evolution of concepts and practices. Comparative Public Administration. 2006;15:433–445. doi: 10.1016/S0732-1317(06)15018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson OE. Markets, Hierarchies, and the Modern Corporation - an Unfolding Perspective. J Econ Behav Organ. 1992;17(3):335–352. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(95)90012-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandler J. Strategy and Structure of Japanese Enterprises - Kono,T. Long Range Plann. 1986;19(6):145. doi: 10.1016/0024-6301(86)90111-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roland A. Transition and Economics: Potitics, Markets and Firms. Cambridge, Ma: MIT Press; 2000.