Abstract

Background

The nurse cell (NC) constitutes in mammalian skeletal muscles a confined intracellular niche to support the metabolic needs of muscle larvae of Trichinella spp. encapsulating species. The main biological functions of NC were identified as hypermitogenic growth arrest and pro-inflammatory phenotype, both inferred to depend on AP-1 (activator protein 1) transcription factor. Since those functions, as well as AP-1 activity, are known to be regulated among other pathways, also by Wnt (Wingless-Type of Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Integration Site) signaling, transcription profiling of molecules participating in Wnt signaling cascades in NC, was performed.

Methods

Wnt signaling-involved gene expression level was measured by quantitative RT-PCR approach with the use of Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays and complemented by that obtained by searching microarray data sets characterizing NC transcriptome.

Results

The genes involved in inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade as well as leading to β-catenin degradation were found expressed in NC at high level, indicating inhibition of this cascade activity. High expression in NC of genes transmitting the signal of Wnt non-canonical signaling cascades leading to activation of AP-1 transcription factor, points to predominant role of non-canonical Wnt signaling in a long term maintenance of NC biological functions.

Conclusions

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade is postulated to play a role at the early stages of NC formation when muscle regeneration process is triggered. Following mis-differentiation of infected myofiber and setting of NC functional specificity, are inferred to be controlled among other pathways, by Wnt non-canonical signaling cascades.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1770-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Trichinella spp., Nurse cell, Wnt signaling, Growth arrest, Inflammatory phenotype, AP-1 transcription factor

Background

The nurse cell (NC) constitutes an intracellular niche for the muscle larvae of parasitic nematode Trichinella spp. Its basic morphological structure, called cyst, is formed within mammalian striated muscles 20–28 days post-oral infection [1, 2]. Larva penetration into the muscles induces degeneration of infected myofiber, followed by its fusion with muscle satellite cells and commencement of regeneration process. However, eventually mis-differentiation takes place and part of the infected myofiber transforms into a non-muscular structure, the NC fulfilling larva metabolic requirements. NC-larva complex confined within a collagen capsule and surrounded by circulatory rete is stably maintained throughout the life span of the host [1]. NC is characterized by hypertrophy and 4 N DNA content [3, 4]. Based on transcription profiling NC growth arrest stage was identified as being of G1-like type accompanied by cellular senescence [5]. NC was also found to display antigen presentation capability and pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype [6].

Wnt signaling pathway plays an important role in morphogenesis and postnatal stem cell fate determination [7, 8]. Inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for cell lineage differentiation but the cascade, if recapitulated in mature differentiated cellular systems, is associated with onset of various diseases, including neurodegeneration and malignancies [9–11]. A role in cellular senescence and aging-associated disorders have been ascribed to various Wnt ligands [12–14]. Physiological responses to Wnt signaling are elicited by diverse cellular functions: cell survival, proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, cell movement and immunological activities [15]. Wnt growth factors bind to transmembrane Frizzled (Fzd) receptors, belonging to G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) family [9]. The signal is subsequently transduced via three distinct routes: the canonical Wnt/β-catenin and two non-canonical Wnt/PCP (Planar Cell Polarity) and Wnt/Ca2+, signaling cascades [15, 16]. Particular Wnt ligand-Fzd receptor interactions are tissue- and process-specific. It is emphasized for Wnt signal transduction that various combinations of ligand-receptor complexes, as well as many regulatory loops and cross-talks, also with other signaling pathways, ultimately lead to a cell-specific type of response [17, 18]. Despite such a diversity, specifically Wnt 4, Wnt 5A and Wnt 11 ligands are considered to activate Wnt non-canonical cascades [18, 19]. Of note, Wnt 5A upregulation was demonstrated to occur in stimulated antigen-presenting cells, i.e. dendritic cells and macrophages [20]. In the case of canonical Wnt signaling route transcription of effector genes is activated by β-catenin transcription activation complex, and in the case of non-canonical Wnt signaling route, by AP-1 transcription factor [15].

As far as skeletal muscles are concerned, Wnt signaling is involved in myogenesis and muscle regeneration. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediated by Wnt 1 and Wnt 7A ligands was shown to induce early myogenesis in mice [21]. Wnt 3A, Wnt 5A/5B and Wnt 7A/7B ligands signaling is considered critical for muscle regeneration, with myoblast differentiation and myotube fusion assumed to be affected [8]. Yet transient β-catenin activation, accompanying this process, is also viewed rather as a vestige from embryonic lineage, crucial for myogenesis but requiring inhibition for muscle regeneration to proceed [22].

As a cellular system, NC originates from muscle cells suspended during regeneration. Immunological activities with signaling pathways culminating at AP-1 transcription factor activation, were identified as its prominent biological functions [6]. Those characteristics should apparently be controlled by Wnt signaling. Additionally, Wnt 2 ligand was found in general analysis of NC transcriptome to be highly upregulated, in comparison to myoblastic cell line [5]. Therefore, the present scrutinized analysis was undertaken, of expression level of factors involved in Wnt signaling in NC, performed with the use of PCR arrays and supported by the search of microarray data sets [5]. The results point to a putative essential role of Wnt factors in setting of NC phenotype.

Methods

NC isolation

Trichinellosis in BALB/c mice, infected with Trichinella spiralis H2 human isolate, was exploited as previously described [23]. NCs were isolated from mice carrying 6 month-old infections by sequential muscle digestion, as earlier presented [5]. NC in a typical preparation is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

NC-Trichinella spiralis larva complex. The nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342 dye (Lonza). The image was taken with Nikon Optiphot-Z fluorescence microscope. Scale-bar: 100 μm

RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays

Qiagen kits were used at all steps. Total RNA was isolated with the use of RNaesy Mini kit, according to manufacturer’s instruction, with implementation of the RNase-Free DNase digestion step. RNA integrity was confirmed using Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer. RT2 First Strand kit was used for reverse transcription. RT2 SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix was used for quantitative PCR on Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Array of Mouse Wnt Signaling Pathway. The run was performed on 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems), including all control reactions recommended by the arrays’ manufacturer. Target gene expression level was calculated according to Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Array handbook, applying the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) used as a reference gene. It is given as 2exp-ΔCT (± average deviation for n = 2), where ΔCT is CT (target gene)-CT (GAPDH). The genes included into RT2 Profiler PCR Array whose threshold cycle fell above 35th cycle were excluded from data presentation.

Microarray data sets searching

In order to complement performed herein transcription profiling of Wnt signaling factors in NC, the previously obtained competitive microarray data sets [5], were searched for identifiers included in Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Array, as well as the identifiers not included in the PCR array but otherwise related to Wnt signaling. In the aforementioned competitive microarray analysis, the transcriptomes of C2C12 myoblasts and C2C12 myotubes served as referral systems to the NC transcriptome. In order to eliminate biological differences among NC preparations, four different preparations of NCs isolated from mice carrying 5 to 12 month-infections were exploited for competitive microarray analysis. Only the identifiers with differential gene expression level ≥ 2 accompanied by a P-value ≤ 0.05, were considered signaling pathway-eligible. Fold change in gene expression level in NC, in relation to C2C12 myoblasts or myotubes, was calculated form log2ratio value and is provided as the average of quadruplicates, accompanied by the P-values calculated by Student’s one-sample t-test. All parameters of statistical analysis, including log2ratio ± standard deviation (SD) as well as the t-values, are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of NC formation process

The NC is a non-muscular structure originating from a few types of cells. During encapsulation of the larva lasting up to 28 days post-infection, the nuclei, mitochondria and basophilic cytoplasm (i.e. staining with haematoxylin in haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining protocol), of infected myofiber, degenerate with the signs of apoptosis and autocrine signaling by tumor necrosis factor α [24, 25]. Inhibition of transforming growth factor β signaling by c-Ski repressor was also shown to accompany this process [26]. Muscle satellite cells, fusing with the infected degenerating myofiber, become the main source of nuclei, mitochondria and eosinophilic cytoplasm (i.e. staining with eosin in H&E staining procedure), in the completely established NC at 3-month-old infection. Some nuclei of NC become hypertrophied at this stage, and infiltrating lymphocytes were also identified entrapped in the NC cytoplasm [27]. It should be noted that during NC formation two various kinds of cytoplasm, basophilic and eosinophilic, are separated by plasma membrane and the whole process in independent on p53 suppressor gene [2, 27, 28]. Analysis of NC transcriptome during the process of intracellular transformation (i.e. 23rd day post-infection), indicated activation of survival mechanism mediated by insulin-like growth factor 1 which may lead to induction of AP-1 transcription factor [29, 30]. Wnt 8A and 5B ligand expression was also found upregulated at this stage of NC development, as analyzed in the whole infected vs uninfected muscle tissue [29]. Wnt canonical signaling cascade inhibitory factor Dickkopf homolog 4 (DKK4 gene) [31], was also found upregulated in those settings [29]. These findings indicate that already at the stage of larva encapsulation Wnt signaling-involved factors shape NC functional specificity towards non-canonical Wnt signaling and AP-1 factor activation, serving to determine survival and immunological properties.

Inhibitory factors of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade are expressed in fully established NC

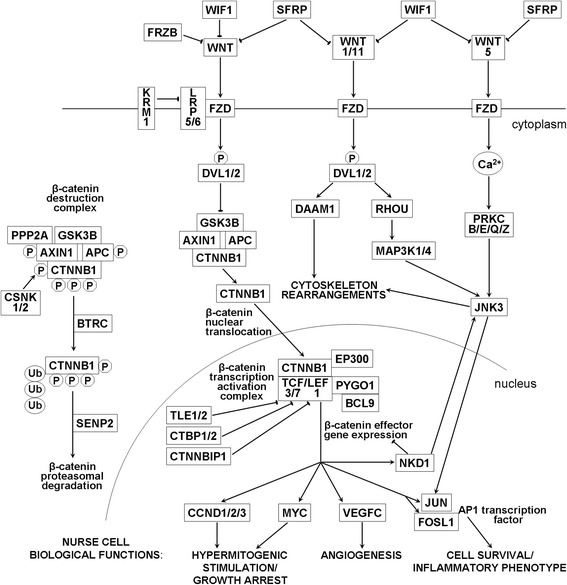

A network of molecules participating in Wnt signaling, whose expression was detected in NC, is depicted in Fig. 2. Gene description and gene expression levels are shown in Table 1. In cells unstimulated by Wnt ligands, central molecule of this cascade, β-catenin (encoded by CTNNB1 gene), is known to remain in the cytoplasm in a phosphorylated form complexed with GSK3B and scaffolding factors APC and AXIN1 [32]. Apart from GSK3B, also casein kinases, represented in NC by CSNK1A1, CSNK1D and CSNK2A1, are known to phosphorylate β-catenin. Additionally, bound with protein phosphatases (PPP2CA, PPP2R1A and PPP2R5D subunits are expressed in NC), β-catenin is ubiqutinated in the presence of BTRC and driven for proteasomal degradation [32]. SENP2 peptidase is also known to participate in downregulation of β-catenin level [33, 34]. Assuming autocrine stimulation to occur, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade can be activated in NC by Wnt 1, Wnt 2/2B, Wnt 3/3A, Wnt 6, Wnt 9A and Wnt 16. Upon stimulation of FZD receptors by Wnt ligands activated Dsh1/2 proteins (encoded by DVL1/2 genes), lead to inhibition of β-catenin phosphorylation. Unphosphorylated β-catenin translocates to the nucleus where it forms a transcription activation complex with TCF/LEF factors, additionally activated by EP300 and BCL9/PYGO1 complex [32]. FZD receptors 1 through 8, coreceptors LRP5/6, as well as DVL1/2, TCF3/7 and LEF1 genes, are expressed in NC, though TCF7 and LEF1 are down regulated in relation to C2C12 cellular systems. Numerous molecules known to inhibit β-catenin transcription activation complex, including TLE1/2, CTBP1/2, CTNNBIP1, as well as an effector, and simultaneously an inhibitor, of this cascade, NKD1 gene product [35], are expressed in NC. NKD1 expression is also very highly upregulated in relation to C2C12 myoblasts/myotubes. Of note, NKD1 is known to switch Wnt signaling from canonical to non-canonical Wnt/PCP cascade [36]. Apart from apparent inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade in NC by intracellular factors, this cascade may also be inhibited at the plasma membrane level. KRM1 (alias KREMEN1), WIF1, FRZB (alias SFRP3) and SFRP1/2/4 gene products, expressed in NC, are known to inhibit Wnt signaling via interaction with LRP5/6 coreceptors (KRM1), binding to Wnt ligands (WIF1 and FRZB) or interaction with both Wnt ligands and Fzd receptors (SFRP1/2/4 factors) [37, 38]. Importance of an inhibitory route of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in NC at the plasma membrane level is further stressed by very high upregulation of FRZB and high upregulation of WIF1 expression in NC, in relation to C2C12 myoblasts/myotubes. Of note is that Wnt 1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 WISP1, known to display anti-apoptotic activity [39], is expressed in NC at the level significantly lower than in C2C12 cellular systems. Effector genes of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade expressed in NC include factors involved in regulation of cell fate and inflammation: cyclins D, c-Myc, Fra1 (encoded by FOSL gene) and c-Jun, as well as angiogenic factor VEGFC [web.stanford.edu/group/nusselab/cgi-bin/wnt/target_genes].

Fig. 2.

Summary of interactions involved in Wnt signaling cascades inferred to regulate NC biological functions. Only the molecules whose expression was detected in NC by RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays and/or microarrays, are marked. Wnt signaling consensus pathway was complied from Wnt signaling pathway available at www.qiagen.com/pl/shop/genes-and-pathways/pathway-details/?pwid=474, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (www.ingenuity.com/products.ipa) and references [9, 15]. Sharp arrows indicate activatory interactions and blunt arrows indicate inhibitory interactions. Descriptions of molecule names are given in Table 1

Table 1.

Expression in NC of molecules involved in Wnt signaling pathway. Gene expression level determined by RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays is given as 2−∆CT, and by competitive microarray approach as a fold change, increase or decrease (↓) in relation to C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes. Data analysis was performed as described under Methods section

| GenBank accession number | Gene symbol | Description | Gene expression 2−∆CT (± AD, n = 2) | Fold change (P-value) in gene expression level in NC vs C2C12 Myoblasts/myotubes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_007462 | APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli | 2.92 ± 0.40 | |

| NM_009733 | AXIN1 | Axin1 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | |

| NM_029933 | BCL9 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | |

| NM_009771 | BTRC | Beta-transducin repeat containing protein | 0.63 ± 0.04 | |

| NM_023465 | CTNNBIP1 | Catenin beta interacting protein 1 | 1.59 ± 0.01 | /2.1 (0.00) |

| NM_007631 | CCND1 | Cyclin D1 | 4.40 ± 0.62 | /9.5 (0.00)* |

| NM_009829 | CCND2 | Cyclin D2 | 19.33 ± 1.41 | 5.1 (0.00)*/7.8 (0.00)* |

| NM_007632 | CCND3 | Cyclin D3 | 2.37 ± 0.64 | 2.1 (0.01)/↓1.9 (0.01) |

| NM_146087 | CSNK1A1 | Casein kinase 1, alpha 1 | 3.85 ± 1.01 | /↓2.1 (0.00) |

| NM_139059 | CSNK1D | Casein kinase 1, delta | 7.36 ± 1.33 | |

| NM_007788 | CSNK2A1 | Casein kinase 2, alpha 1 polypeptide | 9.55 ± 0.80 | ↓2.9 (0.00)/↓3.4 (0.00) |

| NM_013502 | CTBP1 | C-terminal binding protein 1 | 0.38 ± 0.12 | |

| NM_009980 | CTBP2 | C-terminal binding protein 2 | 5.26 ± 0.17 | /2.2 (0.01) |

| NM_007614 | CTNNB1 | Catenin (cadherin associated protein), beta 1 | 2.03 ± 0.40 | |

| NM_172464 | DAAM1 | Dishevelled associated activator of morphogenesis 1 | 5.13 ± 0.47 | |

| NM_010091 | DVL1 | Dishevelled 1, dsh homolog (Drosophila) | 0.48 ± 0.13 | /↓2.2 (0.00) |

| NM_007888 | DVL2 | Dishevelled 2, dsh homolog (Drosophila) | 0.09 ± 0.04 | |

| NM_177821 | EP300 | E1A binding protein p300 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | |

| NM_010234 | FOS | v-FOS murine viral oncogene homolog | 116.7 (0.00)*/27.2 (0.00)* | |

| NM_008036 | FOSB | FBJ murine viral oncogene homolog | 6.0 (0.00)*/5.5 (0.00)* | |

| NM_010235 | FOSL1 | Fos-like antigen 1 | 1.36 ± 0.13 | ↓3.1 (0.00)/2.1 (0.01) |

| NM_011356 | FRZB | Frizzled-related protein | 8.25 ± 2.13 | 21.9 (0.00)/14.8 (0.00) |

| NM_021457 | FZD1 | Frizzled homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 1.36 ± 0.46 | 3.6 (0.00)/ |

| NM_020510 | FZD2 | Frizzled homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 1.20 ± 0.77 | |

| NM_021458 | FZD3 | Frizzled homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 0.39 ± 0.04 | |

| NM_008055 | FZD4 | Frizzled homolog 4 (Drosophila) | 0.35 ± 0.00 | 3.6 (0.01)/ |

| NM_022721 | FZD5 | Frizzled homolog 5 (Drosophila) | 1.97 ± 0.26 | |

| NM_008056 | FZD6 | Frizzled homolog 6 (Drosophila) | 0.22 ± 0.11 | |

| NM_008057 | FZD7 | Frizzled homolog 7 (Drosophila) | 0.07 ± 0.04 | |

| NM_008058 | FZD8 | Frizzled homolog 8 (Drosophila) | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 3.4 (0.00)/2.4 (0.03) |

| NM_019827 | GSK3B | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | 0.75 ± 0.02 | |

| NM_010591 | JUN | Jun oncogene | 7.68 ± 2.99 | 1.9 (0.00)/ |

| NM_010592 | JUND | Jun-D proto-oncogene | 2.5 (0.02)*/2.1 (0.02)* | |

| NM_032396 | KREMEN1 | Kringle containing transmembrane protein 1 | 8.56 ± 0.19 | |

| NM_010703 | LEF1 | Lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | ↓3.7 (0.00)/↓2.4 (0.04) |

| NM_008513 | LRP5 | Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 | 1.43 ± 0.63 | 3.4 (0.00)/3.9 (0.00) |

| NM_008514 | LRP6 | Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 | 1.44 ± 0.09 | |

| NM_011945 | MAP3K1 | MEKK1, MAP kinase kinase kinase 1 | 4.9 (0.00)*/6.7 (0.00)* | |

| NM_011948 | MAP3K4 | MEKK4, MAP kinase kinase kinase 4 | 2.1 (0.00)*/2.0 (0.00) | |

| NM_009158 | MAPK10 | JNK3, Jun-N terminal kinase | 8.8 (0.00)*/6.8 (0.00)* | |

| NM_010849 | MYC | Myelocytomatosis oncogene | 0.88 ± 0.14 | ↓4.7 (0.00)*/↓2.9 (0.01)* |

| NM_027280 | NKD1 | Naked cuticle 1 homolog (Drosophila) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 42.3 (0.00)/27.8 (0.00) |

| NM_008702 | NLK | Nemo-like kinase | 0.38 ± 0.01 | |

| NM_019411 | PPP2CA | Protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2A), catalytic subunit, alpha isoform | 15.79 ± 0.81 | |

| NM_016891 | PPP2R1A | Protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2A), regulatory subunit A (PR 65), alpha isoform | 10.09 ± 0.04 | |

| NM_009358 | PPP2R5D | Protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit B (B56), delta isoform | 0.75 ± 0.14 | |

| NM_008855 | PRKCB1 | Protein kinase C, beta 1 | 10.0 (0.01)*/6.7 (0.00)* | |

| AK017901 | PRKCE | Protein kinase C, epsilon | 4.3 (0.01)*/4.4 (0.00)* | |

| NM_008859 | PRKCQ | Protein kinase C, theta | 6.3 (0.00)*/4.6 (0.01)* | |

| NM_008860 | PRKCZ | Protein kinase C, zeta | 14.6 (0.00)*/10.6 (0.00)* | |

| NM_028116 | PYGO1 | Pygopus 1 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 4.6 (0.00)/3.0 (0.01) |

| NM_133955 | RHOU | Ras homolog gene family, member U | 0.51 ± 0.16 | /2.3 (0.00) |

| NM_029457 | SENP2 | SUMO/sentrin specific peptidase 2 | 1.88 ± 0.05 | |

| NM_013834 | SFRP1 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 | 0.09 ± 0.008 | |

| NM_009144 | SFRP2 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 2 | 0.02 ± 0.012 | /↓5.4 (0.00) |

| NM_016687 | SFRP4 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | |

| NM_009332 | TCF3 | Transcription factor 7-like 1 (T-cell specific, HMG box) | 1.31 ± 0.10 | 2.1 (0.02)/2.6 (0.00) |

| NM_009331 | TCF7 | Transcription factor 7, T-cell specific | 0.46 ± 0.13 | ↓3.2 (0.00)/↓2.3 (0.01) |

| NM_011599 | TLE1 | Transducin-like enhancer of split 1 | 1.10 ± 0.27 | |

| NM_019725 | TLE2 | Transducin-like enhancer of split 2 | 0.005 ± 0.0022 | |

| NM_009506 | VEGFC | Vascular endothelial growth factor C | 5.3 (0.00)*/5.9 (0.00)* | |

| NM_011915 | WIF1 | Wnt inhibitory factor 1 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 6.4 (0.00)/2.5 (0.00) |

| NM_018865 | WISP1 | WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 | 2.22 ± 0.69 | ↓4.9 (0.00)/↓6.1 (0.00) |

| NM_021279 | WNT1 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 1 | 0.003 ± 0.0011 | |

| NM_009519 | WNT11 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 11 | 1.89 ± 0.22 | 6.5 (0.00)/4.1 (0.00) |

| NM_053116 | WNT16 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 16 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 5.6 (0.01)/3.3 (0.00) |

| NM_023653 | WNT2 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 2 | 0.008 ± 0.0029 | 28.2 (0.00)*/21.9 (0.00)* |

| NM_009520 | WNT2B | Wingless related MMTV integration site 2b | 0.03 ± 0.001 | |

| NM_009521 | WNT3 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 3 | 0.002 ± 0.0013 | 3.3 (0.01)/2.4 (0.00) |

| NM_009522 | WNT3A | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 3A | 0.004 ± 0.0022 | |

| NM_009523 | WNT4 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 4 | 0.009 ± 0.0062 | ↓2.9 (0.00)/ |

| NM_009524 | WNT5A | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 5A | 0.03 ± 0.011 | 4.8 (0.01)/3.0 (0.02) |

| NM_009525 | WNT5B | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 5B | 5.89 ± 2.90 | 9.9 (0.00)/7.7 (0.00) |

| NM_009526 | WNT6 | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 6 | 0.03 ± 0.008 | ↓2.8 (0.01)/ |

| NM_139298 | WNT9A | Wingless-type MMTV integration site 9A | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 2.5 (0.00)/↓2.1 (0.00) |

It is thus inferred that dominant expression in NC of molecules involved in β-catenin degradation as well as inhibition of canonical Wnt signal transduction and β-catenin-dependent transcription, indicate that even though could be operating, Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade is inhibited. Expression of the cascade effector genes may have resulted from Wnt/β-catenin-activated transcription at the earlier stages of NC formation, but in fully established NC this regulation seems to be attributed rather to other signaling pathways.

Effector factors of non-canonical Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ signaling cascades are expressed in fully established NC

A network of molecules participating in non-canonical Wnt signaling cascades, whose expression was detected in NC, is schematically depicted in Fig. 2, with gene descriptions and expression level values provided in Table 1. Non-canonical Wnt signaling was shown in various cellular systems to be stimulated by Wnt 1/11 and Wnt 5A ligands [15, 40, 41]. Wnt 11 and Wnt 5B are expressed in NC at the highest level among other Wnt ligands. Their expression, as well as the expression of Wnt 5A, is also upregulated in relation to C2C12 myoblasts/myotubes. Similar to the canonical cascade, activation of Wnt/PCP cascade occurs via phosphorylation of Dsh proteins [16]. In NC, the signal can be transduced downstream by DAAM1 factor and RHOU-MAP3K1/4-JNK3 axis, to induce cytoskeleton rearrangements. JNK3 can also be activated in NC via Ca2+ and protein kinase C axis, known to be activated also by classical GPCRs. JNK3 phosphorylates c-Jun and JunD which then dimerise with one of the Fos proteins to form transcription factor AP-1, known to display prosurvival and proinflammatory action, as well as to inhibit myogenesis [16, 42–47]. Expression of c-Jun, JunD, Fra-1 (encoded by FOSL1 gene), FosB and Fos is found in NC, with Fos being the most highly upregulated gene in relation to C2C12 cellular systems. Thus expression in NC of Wnt 11, Wnt 5A/5B ligands, as well as JNK3 and Jun/Fos factors, indicate importance of AP-1 factor in maintenance of NC biological functions mediated by non-canonical Wnt signaling cascades. One of the effector genes of Wnt/Ca2+ signaling cascade, expressed in NC, is Nemo-like kinase (NLK, Table 1). As NLK is known to suppress β-catenin-dependent transcription [48], its expression in NC further points to inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling cascade.

It is inferred from the study performed that canonical, as well as non-canonical cascades operate in NC at the various stages of its formation. Expression in the fully established NC of Wnt ligands responsible for activation of canonical Wnt signaling cascade, the latter known to accompany induction of muscle regeneration [8, 22], may reflect the vestiges from those stages of NC formation when muscle regeneration was triggered. Eventually the cascade inhibition prevails. It is also possible that expression in fully established NC of the cascade inhibiting factors, including a feedback inhibitor NKD1, is indicative of execution of a tight control of the remaining activity of canonical Wnt signaling. It can be hypothesized that at the time point of larva penetration Wnt autocrine signaling may be responsible for β-catenin-dependent induction of infected myofiber regeneration. As no differentiation ultimately occurs, probably due to influence of EGF (epidermal growth factor)/FGF (fibroblast growth factor)/PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor)- induced proliferative stimulation [5], Wnt 5A/5B- and Wnt 11-activated non-canonical signaling cascades sustain the activation of AP-1 transcription factor to regulate NC growth arrest and immunological functions [6]. Current analysis was based on putative loops of autocrine signaling operating in NC. Parasite-derived factors and paracrine signaling should also control NC formation and the functioning of NC at fully established stage. Long-term maintenance of NC biological specificity apparently results from a precise orchestration of various cellular signaling events. The nature of the exact factor causing transformation of muscular cells to the parasite-favorable environment, remains to be identified.

Conclusions

The NC is an intracellular habitat for Trichinella spp. muscle larvae. Assuming autocrine signaling by Wnt ligands to occur during a long-term existence of the NC-Trichinella muscle larva complex, the canonical Wnt signaling cascade is inferred to be inhibited, but the non-canonical Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ cascades are postulated to lead to maintenance of AP-1 transcription factor activation and execution of NC biological functions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by National Science Center grant no. 2011/01/B/NZ6/01781.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and Additional file 1.

Authors’ contributions

MD performed NC isolation, PCR arrays and pathway analysis. MS performed microarray data analysis. ZZ carried out parasite culture. WR coordinated implementation of the project. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the First Warsaw Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation at the Nencki Institute.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- H&E

haematoxylin and eosin

- NC

nurse cell

- PCP

planar cell polarity

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- Wnt

Wingless-type of mouse mammary tumor virus integration site

Additional file

The parameters of statistical analysis of competitive expression microarray data showing gene expression level in NC related to either C2C12 myoblasts or myotubes. Only the genes referred to in Table 1 and Fig. 2 of the main body of the publication, are shown. (DOC 70 kb)

Contributor Information

Magdalena Dabrowska, Email: m.dabrowska@nencki.gov.pl.

Marek Skoneczny, Email: kicia@ibb.waw.pl.

Zbigniew Zielinski, Email: z.zielinski@nencki.gov.pl.

Wojciech Rode, Email: w.rode@nencki.gov.pl.

References

- 1.Despommier DD. How does Trichinella spiralis make itself at home? Parasitol Today. 1998;14:318–323. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(98)01287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boonmars T, Wu Z, Nagano I, Takahashi Y. What is the role of p53 during the cyst formation of Trichinella spiralis? A comparable study between knockout mice and wild type mouse. Parasitology. 2005;131:705–712. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jasmer DP. Trichinella spiralis infected muscle cells arrest in G2/M and cease muscle gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:785–793. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasmer DP. Trichinella spiralis: subversion of differentiated mammalian skeletal muscle cells. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80155-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabrowska M, Skoneczny M, Zielinski Z, Rode W. Nurse cell of Trichinella spp. as a model of long-term cell cycle arrest. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2167–2178. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabrowska M. Inflammatory phenotype of the nurse cell harboring Trichinella spp. Vet Parasitol. 2013;194:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development. 2009;136:3205–3214. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsivitse S. Notch and Wnt signaling, physiological stimuli and postnatal myogenesis. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:268–281. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signaling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers S, Mu D. Genetic similarities between organogenesis and tumorigenesis of the lung. Cell Cycle. 2008;2:200–204. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.2.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verani R, Cappuccio I, Spinsanti P, Gradini R, Caruso A, Magnotti MC. Expression of the Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 is required for the induction of neural markers in mouse embryonic stem cells differentiating in response to retinoic acid. J Neurochem. 2007;100:242–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, Banumathy G, Zhang R, Adams PD. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;27:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;317:803–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, Lee M, Kuo CJ, Keller C, Rando TA. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science. 2007;317:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1144090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staal FJT, Tiago CL, Tiemessen MM. WNT signaling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai S-L, Chien AJ, Moon RT. Wnt/Fzd signaling and the cytoskeleton: potential roles in tumorigenesis. Cell Res. 2009;19:532–545. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niehrs C. The complex world of WNT receptor signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:767–779. doi: 10.1038/nrm3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nusse R. Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 2005;15:28–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlessinger K, Hall A, Tolwinski N. Wnt signaling pathways meet Rho GTPases. Genes Dev. 2009;23:265–277. doi: 10.1101/gad.1760809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehtonen A, Ahlfors H, Veckman V, Miettinen M, Lahesmaa R, Julkunen I. Gene expression profiling during differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages or dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:710–720. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryson-Richardson RJ, Currie PD. The genetics of vertebrate myogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:632–646. doi: 10.1038/nrg2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy MM, Keefe AC, Lawson JA, Flygare SD, Yandell M, Kardon G. Transiently active Wnt/β-catenin signaling is not required but must be silenced for stem cell function during muscle regeneration. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabrowska M, Zielinski Z, Wranicz M, Michalski R, Pawelczak K, Rode W. Trichinella spiralis thymidylate synthase: developmental pattern, isolation, molecular properties, and inhibition by substrate and cofactor analogues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:440–445. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boonmars T, Wu Z, Nagano I, Takahashi Y. Expression of apoptosis-related factors in muscles infected with Trichinella spiralis. Parasitology. 2004;128:323–332. doi: 10.1017/S0031182003004530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Nagano I, Boonmars T, Takahashi Y. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-mediated apoptosis in Trichinella spiralis-infected muscle cells. Parasitology. 2005;131:373–381. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005007663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Nagano I, Boonmars T, Takahashi Y. Involvement of the c-Ski oncoprotein in cell cycle arrest and transformation during nurse cell formation after Trichinella spiralis infection. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuo A, Wu Z, Nagano I, Takahashi Y. Five types of nuclei present in the capsule of Trichinella spiralis. Parasitology. 2000;121:203–210. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099006198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Z, Matsuo A, Nakada T, Nagano I, Takahashi Y. Different response of satellite cells in the kinetics of myogenic regulatory factors and ultrastructural pathology after Trichinella spiralis and T. pseudospiralis infection. Parasitology. 2001;123:85–94. doi: 10.1017/S0031182001007958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, Nagano I, Boonmars T, Takahashi Y. A spectrum of functional genes mobilized after Trichinella spiralis infection in skeletal muscle. Parasitology. 2005;130:561–573. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004006912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Z, Sofronic-Milosavljevic L, Nagano I, Takahashi Y. Trichinella spiralis: nurse cell formation with emphasis on analogy to muscle cell repair. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:27. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zorn AM. Wnt signaling: Antagonistic Dickkopfs. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R592–R595. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Baster K. β-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:276–286. doi: 10.1038/nrm2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadoya T, Kishida S, Fukui A, Hinoi T, Michiue T, Asashima M, Kikuchi A. Inhibition of Wnt signaling pathway by a novel axin-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37030–37037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishida T, Kanedo F, Kitagawa M, Yasuda H. Characterization of a novel mammalian SUMO-1/Smt3-specific isopeptidase, a homologue of rat axam, which is an axin-binding protein promoting β-catenin degradation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39060–39066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angonin D, Van Raay TJ. Nkd1 functions as a passive antagonist of Wnt signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katoh M. WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:1583–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao B, Wu W, Davidson G, Marhold J, Li M, Melcher BM, et al. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Nature. 2002;417:664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su F, Overholtzer M, Besser D, Levine AJ. WISP-1 attenuates p53-mediated apoptosis in response to DNA damage through activation of the Akt kinase. Genes Dev. 2002;16:46–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.942902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao E, Pennica D, Xu L, Kalejta RF, Levine AJ. Wrch-1, a novel member of the Rho gene family that is regulated by Wnt-1. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1796–1807. doi: 10.1101/gad.894301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De A. Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway: a brief overview. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2011;43:754–756. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conejo R, Valverde AM, Banito M, Lorenzo M. Insulin produces myogenesis in C2C12 myoblasts by induction of NF-kB and downregulation of AP1 activities. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:82–94. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200101)186:1<82::AID-JCP1001>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson GL, Nakamura K. The c-Jun kinase/stress-activated pathway: regulation, function and role in human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kallunki T, Deng T, Hibi M, Karin M. c-Jun can recruit JNK to phosphorylate dimerization partners via specific docking interactions. Cell. 1996;87:929–939. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li M-D, Yang X. A retrospective on nuclear receptor regulation of inflammation: lessons from GR and PPARs. PPAR Res. 2011;2011:742785. doi: 10.1155/2011/742785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a006049. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park K, Chung M, Kim S-J. Inhibition of myogenesis by okadaic acid, an inhibitor of protein phosphatases, 1 and 2A, correlates with the induction of AP1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10810–10815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grigoryan T, Wend P, Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Deciphering the function of canonical Wnt signals in development and disease: conditional loss- and gain-of-function mutations of β-catenin in mice. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2308–2341. doi: 10.1101/gad.1686208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and Additional file 1.