Abstract

Background

Hip fractures are an increasingly common consequence of falls in older people that are associated with a high risk of death and reduced function. This review aims to quantify the impact of hip fracture on older people’s abilities and quality of life over the long term.

Methods

Studies were identified through PubMed and Scopus searches and contact with experts. Cohort studies of hip fracture patients reporting outcomes 3 months post-fracture or longer were included for review. Outcomes of mobility, participation in domestic and community activities, health, accommodation or quality of life were categorised according to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning and synthesised narratively. Risk of bias was assessed according to four items from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

Results

Thirty-eight studies from 42 publications were included for review. Most followed a clearly defined sample from the time of fracture. Hip fracture survivors experienced significantly worse mobility, independence in function, health, quality of life and higher rates of institutionalisation than age matched controls. The bulk of recovery of walking ability and activities for daily living occurred within 6 months after fracture. Between 40 and 60 % of study participants recovered their pre-fracture level of mobility and ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living, while 40–70 % regained their level of independence for basic activities of daily living. For people independent in self-care pre-fracture, 20–60 % required assistance for various tasks 1 and 2 years after fracture. Fewer people living in residential care recovered their level of function than those living in the community. In Western nations, 10–20 % of hip fracture patients are institutionalised following fracture. Few studies reported impact on participation in domestic, community, social and civic life.

Conclusions

Hip fracture has a substantial impact on older peoples’ medium- to longer-term abilities, function, quality of life and accommodation. These studies indicate the range of current outcomes rather than potential improvements with different interventional approaches. Future studies should measure impact on life participation and determine the proportion of people that regain their pre-fracture level of functioning to investigate strategies for improving these important outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0332-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hip fracture, Recovery of function, Mobility limitation, Activities of daily living, Institutionalisation, Quality of life, Osteoporosis, Aged, Longterm care, Review

Background

World-wide, people are living longer, with an increase in the proportion of older people in the population [1]. The greater understanding we have of the conditions that predominantly affect older people, the more prepared society can be to maximise health, opportunities and societal contributions for older people.

The health of bones, muscles and joints commonly deteriorates with advancing age. With increased age, there is a decrease in bone mineral density as well as muscle mass and strength [2] and the risk of falls and fall related injury increases [3]. The relative contribution of physiological ageing, chronic disease and inactivity to this deterioration is not yet understood but it is clear that there is an increased risk of fragility fractures, fractures that occur as a result of a low energy trauma (a fall from standing height or less) with increasing age.

Hip fractures are a common consequence of falls in older people and are particularly devastating in terms of their impact on an individual’s health and abilities. An estimated 95 % of hip fractures are due to falls [4]. The estimated annual prevalence of hip fractures globally is expected to reach 4.5 million by 2050 [5]. The highest aged-standardised rates of hip fracture due to osteoporosis are in North America and Europe [6]. Growth is also anticipated in other highly populated areas of the world, including countries in Asia, the Middle East and South America [1]. However while the age specific incidence is decreasing in a number of countries, population ageing in higher income countries is driving increases in the prevalence of hip fracture [7].

In high-income countries, most hip fractures are treated surgically, with admission to acute hospital care and, at times, a subsequent admission to a rehabilitation facility. Many older people who experience a hip fracture fail to fully recover. Many studies of hip fracture outcomes have been conducted but their findings regarding the long-term impact of hip fracture on independence in terms of mobility, activities of daily living (ADL) and life participation for older people are yet to be synthesised.

The aim of the current review was to provide an estimate of the impact of hip fracture on older people’s abilities over the long term. Large cohort studies reporting outcomes of activity and participation, health and quality of life 3 months or longer after hip fracture are reviewed.

Methods

A critical review of cohort studies of hip fracture patients reporting outcomes of mobility, participation in domestic and community activities, health or quality of life at 3 months post-fracture or longer was conducted, following a protocol developed a priori. This review was developed within a rapid time frame and contains many similarities to evolving rapid review methodology [8]; it has a clearly defined review question based on the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) criteria, the review question and protocol were developed a priori, selection of studies is based on inclusion criteria and includes rigorous critical appraisal, summary and categorisation of the outcome data and interpretation of the findings is informed by the quality appraisal of the studies. Included studies had enrolled ≥75 % of patients aged over 60 years or the mean age was over 60 years, or enrolled only patients with a hip fracture due to a low energy trauma. Studies enrolling patients on the basis of the type of intervention received were excluded. Studies enrolling only those patients managed surgically (but ideally not a single type of surgery) were included as this is considered standard care in more developed countries.

Studies were identified by searching in PubMed, Scopus and hip fracture registries in November - December 2015 as well as through existing systematic reviews [9], reference lists of included studies and contact with experts.

Risk of bias was assessed according to four items adapted from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [10, 11] and Altman [12]; the items were rated as yes, no or unclear. The four items considered were (a) “Is it a representative sample?” this item was rated ‘yes’ if recruitment was consecutive or random; (b) “Were patients followed from inception?” This item was rated ‘yes’ if baseline time was same for all patients and close to fracture time, ratings considered whether or not patients were followed from inception rather than enrolled at inception– thus studies also scored ‘yes’ if data was recorded from time of admission; (c) “Is it a clearly defined sample?” This item was rated ‘yes’ if enrolment was for hip fracture according to hospital diagnosis with an age limit. Lastly, (d) “Was there adequate follow-up?” This item was rated ‘yes’ if more than 80 % of enrolled participants contributed follow-up data at 3 months or longer.

Results were extracted and outcomes categorised as primarily assessing activities (the execution of a task or action by an individual) or participation (involvement in a life situation) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework [13]. Additional outcome categories were health condition, accommodations or quality of life.

It was not possible to synthesise all reported outcomes data from all studies identified that met the eligibility criteria. Thus this article includes and summarises data from the studies that reported outcomes as: (a) comparisons to a non-fracture group; (b) the time to recovery of function (or recovery at multiple follow-up times after hip fracture); (c) the proportion recovering pre-fracture function; (d) impact on function for those living in residential care. For outcomes where data was sparse, this was supplemented with some data from studies reporting outcomes at a single time point or from other countries. Where data were only reported in graphical form, they were not extracted for review. Outcomes at discharge or other time points earlier than 3 months were not extracted for review.

Proportion/percentage calculations from numerator and denominator were not verified, except where the data are presented in this review graphically. The proportion followed-up was calculated as the number of known deaths plus those with follow-up data as a proportion of those enrolled, wherever possible (ie known deaths + followed-up/ N enrolled). Where calculation of the proportion followed up could not be verified, the value as reported in the original publication was accepted. Where possible, the proportion of participants institutionalised (i.e., moving to residential aged care) was determined as the number institutionalised divided by the number surviving and not institutionalised at baseline, rather than the proportion of the total study population enrolled. The findings were synthesised in a narrative summary of the studies.

Results

Study characteristics

Data from 38 cohort studies reported in 42 publications were reviewed. Three studies (in four publications) reported outcomes in people sustaining a hip fracture within longitudinal population-based prospective cohort studies, thus pre-fracture ability and participation outcomes were recorded prospectively [14–17]. Eight studies reported outcomes for people following hip fracture in comparison to a non-fracture cohort [16–23]. In the remaining studies, pre-fracture function was determined retrospectively i.e. by participant or proxy interview after the fracture. Cohorts were primarily identified from hospital admission, surgery or discharge records or from government funding claims (eg Medicare in the USA).

A summary of the studies included, their size, country of origin and the outcomes included in this review is provided in Table 1. Seven studies were retrospective in design [12, 23–28], identifying hip fracture patients from hospital, health care or medical claims databases; the remainder were prospective (i.e. participants were identified on admission or discharge from hospital). Most studies stated that they excluded patients with pathological fractures, fractures secondary to other medical conditions or multiple fractures. One US study enrolled patients identified by Medicare claims into a longitudinal study with intentional oversampling of those 80 years of age or over, hence the average age was higher than in most other studies [14]. One study was a cohort of patients with trochanteric fractures treated by Ender nailing; this study was included as it reported on change in self-care outcomes, for which few studies were identified [29]. The majority of studies included patients aged 60 or 65 years and over, although nine studies included patients aged 50 years or over [12, 18, 24, 25, 30–36]. Eight studies specifically enrolled patients with hip fracture as a result of low-impact trauma or falls [12, 23, 27, 33, 36–39]; one included patients with fractures obtained from low to moderate energy trauma [30]. The remaining studies did not use the type of trauma that the injury was sustained from as an eligibility criterion. In most studies, three quarters or more of the participants were women. Three studies only enrolled women [12, 18, 40]. No studies reporting longer-term functional outcomes from hip fracture conducted in an African country were identified.

Table 1.

Summary of included cohort studies, with outcomes included in review categorised using ICF frameworka

| Author, year | Country | N (hip fracture) | Recruitment | Activity | Participation | Health condition | Accomm | QOL | Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Basic ADL | Self care | IADLs | Domestic | Community | ||||||||

| Relative to non-fracture group | |||||||||||||

| Autier 2000 [18]b | Belgium | 170 | 1995–1996 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Boonen 2004 [19]b | Belgium | 170 | 1995–1996 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Cumming 1996 [20] | Australia | 131 | 1990–1992 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Magaziner 2003c [21] | USA | 594 | 1990–1991 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Marottoli 1992d, e [16] | USA | 120 | 1982–1988 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Norton 2000 [22] | New Zealand | 911 | 1991–1994 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Tosteson 2001 [23] | USA | 67 | NR | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Wolinsky 1997e [17] | USA | 368 | 1984–1991 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Population-based cohorts | |||||||||||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | USA | 495 | 1993–2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Marottoli 1994d [15] | USA | 120 | 1982–1988 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| No comparison group | |||||||||||||

| Abimanyi-Ochom 2015 [30] | Australia | 224 | 2009–2012 | Yes | |||||||||

| Beaupre 2005 [50]f | Canada | 919 | 1999–2000 & 1996–1997 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Beaupre 2007 [48]f | Canada | 451 | 1999–2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Borgquist 1990 [31] | Sweden | 103 | 1976–1977 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Borgquist 1991 [32] | Sweden | 837 | 1986–1988 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Borgström 2013 [33] | International | 1273 | 2003, 2007–2010 | Yes | |||||||||

| Crotty 2000 [49] | Australia | 215 | 1998–1999 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Doshi 2014 [61] | Singapore | 219 | 2011–NR | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Givens 2008 [52] | USA | 126 | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Griffin 2015 [46] | UK | 741 | 2012–2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Holt 2008 [62] | Scotland | 16380 | 1998–2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Keene 1993 [41] | UK | 1000 | 1989–1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Kitamura 1998 [34]g | Japan | 1169 | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Tsuboi 2007 [35]g | Japan | 963 | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Koval 1998 [44] | USA | 631 | 1987–1995 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Koval 1998 [51] | USA | 398 | 1988–1990 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Magaziner 1990 [42] | USA | 760 | 1984–1986 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Magaziner 2000c [43] | USA | 674 | 1990–1991 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Miller 2009 [40] | USA | 205 | 1992–1995 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Morin 2012 [24] | Canada | 12139 | 1986–2006 | Yes | |||||||||

| Neuman 2014 [28] | USA | 60111 | 2005–2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Osnes 2004 [25] | Norway | 1002 | 1996–1997 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Pereira 2010 [39] | Brazil | 246 | 2001 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Pitto 1994 [29] | Italy | 143 | 1985–1987 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Samuelsson 2009 [45] | Sweden | 2134 | 2003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Shah 2001 [47] | USA | 850 | 1987–1996 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Ström 2008 [36] | Sweden | 283 | NR | Yes | |||||||||

| Suriyawongpaisal 2003 [26] | Thailand | 250 | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Vergara 2014 [38] | Spain | 638 | NR | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Vochteloo 2013 [37] | Netherlands | 390 | 2008–2009 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Wang 2015 [12] | China | 1151 | 2008–2012 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Wong 2002 [27] | Singapore | 274 | 1991–1993 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

aYes indicates how the study outcomes are categorised according to the ICF framework

b, c, d, f, g indicates hip fracture patients from same cohort

ePopulation-based cohort study with comparison to non-fracture group

Accomm accommodations, ADL activities of daily living, IADL instrumental activities of daily living, ICF International Classification of Functioning, NR not reported, QOL quality of life

Risk of bias

Risk of bias assessment for the reviewed studies is shown in Table 2. Almost all included studies (37/42) followed participants from inception and included a clearly defined sample of participants with hip fracture. Two retrospective studies were enrolled via an invitation to provide follow-up data by questionnaire [23, 25]. The timing of enrolment was unclear in one Italian study [29] and no age limit for enrolment was reported in a large cohort from the United Kingdom (UK) and a retrospective study from Thailand (although all patients were over 50 years of age for the latter) [26, 41]. One fifth of the studies (8/42) did not include a representative sample and 36 % (15/42) of studies had inadequate follow-up, with follow-up data reported from less than 80 % of participants.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies

| Study | Representativei | Inceptionj | Defined samplek | Adequate Follow-upl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative to non-fracture group | ||||

| Autier 2000a [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Boonen 2004a [19] | Y | Y | Y | Yh (QOL = N) |

| Cumming 1996 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Magaziner 2003b [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Marottoli 1992c,d [16] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Norton 2000 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tosteson 2001 [23] | Y | N | Y | U |

| Wolinsky 1997d [17] | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Population-based cohorts | ||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | N | Y | Y | N |

| Marottoli 1994c [15] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| No comparison group | ||||

| Abimanyi-Ochom 2015 [30] | U | Y | Y | N |

| Beaupre 2007 [48]e | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Beaupre 2005 [50]e | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Borgquist 1990 [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Borgquist 1991 [32] | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Borgström 2013 [33] | U | Y | Y | U |

| Crotty 2000 [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Doshi 2014 [61] | U | Y | Y | U |

| Givens 2008 [52] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Griffin 2015 [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Holt 2008 [62] | N | Y | Y | N |

| Keene 1993 [41] | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Kitamura 1998 [34]f | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Tsuboi 2007 [35]f | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Koval 1998 [44]g | N | Y | Y | N |

| Koval 1998 [51]g | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Magaziner 1990 [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Magaziner 2000b [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Miller 2009 [40] | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Morin 2012 [24] | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Neuman 2014 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Osnes 2004 [25] | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Pereira 2010 [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pitto 1994 [29] | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Samuelsson 2009 [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shah 2001 [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ström 2008 [36] | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Suriyawongpaisal 2003 [26] | Y | N | U | U |

| Vergara 2014 [38] | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Vochteloo 2013 [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Wang 2015 [12] | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Wong 2002 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y |

a, b, c, e, f, g indicates hip fracture patients from same cohort

d Population-based cohort study with comparison to non-fracture group

h For ADL and mobility outcomes

i Rated yes if recruitment was consecutive or random; j rated yes if baseline time was same for all patients and close to fracture time; k rated yes if enrolment was for hip fracture according to hospital diagnosis with a defined age limit; l rated yes if ≥80 % of participants contributed follow-up data at ≥ 3 months

QOL Quality of Life, Y yes, N no, U unclear

Activity outcomes

Mobility

Twenty-eight studies reported mobility outcomes (Table 1). Five studies provided a comparison to mobility outcomes for a non-fracture population (Table 3), four publications from three cohorts were population-based cohort studies [14–17] and 20 additional studies were cohorts with pre-fracture status determined retrospectively.

Table 3.

Outcomes for hip fracture patients and control participants not experiencing hip fracture

| Study | Outcome | Follow-up time | Controls matched for | Hip Fracture | Control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity - Mobility | ||||||

| Boonen 2004 [19] | Unable to walk independently | 1 year | age, residence | |||

| <80 years | 30 % | 7 % | <0.001 | |||

| >80 years | 56 % | 15 % | <0.001 | |||

| Magaziner 2003 [21] | Disabled walking 3 m (SE) | 1 year | age, gender, walking ability | 54 % (2) | 21 % (2) | <0.01 |

| Marottoli 1992 [16] | Walk independently across room | 6 mo (HF) | age, gender, physical function | 15 % | NR | |

| 1 year (Con) | 72 % | |||||

| Norton 2000 [22] | Retain community mobility | 2 years | age, gender | 54 % | 87 % | P < 0.001e |

| Wolinsky 1997 [17] | Mean increase in no. lower body limitations | Median 2.3 years | nilf | 1.75 | 0.75 | P ≤ 0.0001 |

| Mean increase in no. upper body limitations | 0.50 | 0.27 | P < 0.001 | |||

| Activity - Composite measure of Basic ADLs | ||||||

| Boonen 2004 [19] | Mean RDRS-2 score for assistance with ADL (95 % CI) | 1 year | age, residence | 8.6 (7.5–9.9) | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) | <0.001 |

| Norton 2000 [22] | Retain functional independence | 2 years | age, gender, independence | 72 % | 94 % | P < 0.001e |

| Tosteson 2001 [23] | Limited daily activities | 1–5 years | nil | 59 % | 13 % | <0.05c |

| Wolinsky 1997 [17] | Mean increase in no. ADL limitations | Median 2.3 years | nilf | 2.08 | 0.79 | P ≤ 0.0001 |

| Activity - Self-care | ||||||

| Magaziner 2003 [21] | Requiring assistance with grooming (SE)i | 1 year | age, gender, walking ability | 17 % (2) | 9 % (1) | P < 0.001 |

| 2 years | 18 % (2) | 10 % (1) | P < 0.001 | |||

| Marottoli 1992 [16] | Dressing independently | 6 mo (HF) | age, gender, physical function | 49 % | - | NR |

| 1 year (Con) | - | 91 % | ||||

| Tosteson 2001 [23] | Difficulty putting on socks | 1–5 years | nil | 43 % | 13 % | P < 0.05 |

| Participation – domestic life | ||||||

| Wolinsky 1997 [17] | Mean increase in no. household ADL limitationsg | Median 2.3 years | nilf | 0.89 | 0.45 | P ≤ 0.0001 |

| Participation – IADLs | ||||||

| Wolinsky 1997 [17] | Mean increase in no. advanced ADL limitationsh | Median 2.3 years | nilf | 0.44 | 0.26 | P < 0.01 |

| Health condition | ||||||

| Boonen 2004 [19] | Mean RDRS-2 score (95 % CI): | 1 year | age, residence | |||

| Dependenceb | 3.1 (2.6–2.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | <0.001 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | <0.001 | |||

| Accommodation | ||||||

| Autier 2000 [18] | Institutionalisation | 1 year | age, residence | 20 % | 4 % | |

| Cumming 1996 [20] | Institutionalisation | 1 year | nil | 27 % | 5 % | <0.05d |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| Boonen 2004 [19] | Mean (95 % CI) RDRS-2 score for QOL (inverted, higher indicates poorer QOL) | 1 year | age, residence | 38.9 (34.3–43.5) | 31.5 (27.5–37.5) | <0.001 |

| Tosteson 2001 [23] | Mean QALY (95 % CI) | 1–5 years | nil | 0.63 (0.52, 0.74) | 0.91 (0.88, 0.94) | <0.051a |

Abbreviations: ADL activities of daily living, Con control, HF hip fracture, mo months, NR not reported, QALY quality adjusted life years, QOL quality of life, RDRS-2 Rapid Disability Rating Scale version-2, SE standard error

aDifference remained after adjustment for age and hormone replacement therapy use

bFor hearing, sight, communication, staying in bed during the day, incontinence and medication

cDifference remained after adjustment for age

dHR significantly different to 1.0 (HR = 4.0, 95 % CI 1.7 – 9.5) after adjustment for age, sex, mental state score, use of proxy respondent, living alone, living with spouse, physical activity (time spent working and/ or walking), number of self-reported medical conditions and self-reported history of myocardial infarction or Parkinson’s disease

eAfter controlling for differences in age, gender and baseline mobility/functional independence

fControls represent those in the prospective cohort that did not experience hip fracture

gIncludes four items from Duke: meal preparation, shopping, light and heavy housework

hIncludes managing money, using telephone and eating

iControl cohort reported is Iowa EPESE cohort; two other control cohorts also reported, with consistent findings

Comparison to a non-fracture group

Studies from three different countries demonstrated that mobility 1 to 2 years following hip fracture is significantly worse than for matched control subjects (Table 3) [19, 21, 22]. A United States (US) study of people residing in the community estimated that the excess number of people disabled after 2 years was 26 per 100 people with hip fracture for walking 3 metres (10 ft) and 22 per 100 for bed transfers [21]. A New Zealand study reported that people experiencing hip fracture were four times more likely to be unable to mobilise in the community 2 years after fracture (OR 4.2, 95 % CI 2.8–6.2, p < 0.001) [22].

A US population-based cohort study of ageing found those sustaining a hip fracture had a statistically significant increase in the number of upper and lower body limitations 2 years after the fracture, in comparison to the remainder of the cohort [17]. The mean increase in the number of limitations in those with hip fracture was 0.93 for the lower body (p = 0.0001) and 0.26 for the upper body (p = 0.02), in comparison to those without hip fracture, after adjusting for baseline differences between the groups [17]. However, there is some uncertainty in these findings as fewer than 80 % of hip fracture patients contributed follow-up data in this study.

Time to recovery

Two US studies from the same US centre provided estimates of the time to recovery (Additional file 1: Table S4) [42, 43]. A study of hip fracture patients from the 1980s found that most patients who recover their pre-fracture walking ability do so within the first 6 months after discharge from hospital [42]. However, over the following 6-month period, a further 10 % of patients regained their walking ability while a similar proportion declined. Time for recovery of different mobility activities varied, ranging from approximately 10 months for chair rise speed to 14 months for walking 3 metres (10 feet) without assistance [43].

Two studies have indicated that the proportion recovering their pre-fracture mobility can continue to increase beyond 3 months (Table 4) [37, 44]. However as these data represent mobility in survivors, this may indicate longer survival of those with better mobility. Seven studies reported absolute walking or mobility rates at multiple time points following hip fracture (see Additional file 1: Table S1). In Swedish and Japanese studies, the proportion of surviving patients walking was found to be similar at 4 months and 1 to 2 years [31, 34, 45] and in community living people the proportion of survivors walking remained relatively constant to 10 years [31]. In contrast, a UK study found some increase in the proportion walking at 1 year [46].

Table 4.

Proportion of survivors that recover their pre-hip fracture levels of activity, participation or health outcomes

| Study | Outcome measure | Pre-fracture residence | Surgical cohort | 3–4 months | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity – Mobility | |||||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | Mobility activities without difficultye | NR | N | 47 % | |||

| Crotty 2000 [49] | Level of ambulationb | Community | Y | 69 % | |||

| LTC | Y | 58 % | |||||

| Holt 2008 [62] | Walk unaided and unaccompanied | Mixed | Y | ||||

| Ages 75–89 | 22 % | ||||||

| Ages ≥95 | 2 % | ||||||

| Keene 1993 [41] | Walk unaided | Mixed | N | 40 % | |||

| Koval 1998 [44]g | Ambulatory ability | Community | Y | 22 % | 38 % | 47 % | |

| Shah 2001 [47]g | Ambulation independence | Community | Y | 44 % | |||

| Magaziner 2000 [43] | Walk 3 m without assistancea, d | Community | N | 60 % | 63 % | ||

| Norton 2000 [22] | Retain community mobilityd | Mixed | U | 54 % | |||

| Osnes 2004[25] | Walking independencef | Mixed | U | 44 % | |||

| Pereira 2010 [39] | Remain stable on BOASd | 55 % | |||||

| Vochteloo 2013 [37] | Mobility | Mixed | Y | 46 % | 48 % | ||

| Mobility without aid | Y | 27 % | 40 % | ||||

| Mobility with aid | Y | 58 % | 58 % | ||||

| Activity – Composite measure of Basic ADLs | |||||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | ADLs without difficultye | NR | N | 49 % | |||

| Beaupre 2005 [50]h | ADL level (MBI) | Mixed | Y | 34 % | 42 % | ||

| Beaupre 2007 [48]h | ADL level (MBI) | Community | Y | 71 % | |||

| LTC | Y | 22 % | |||||

| Givens 2008 [52] | ADL no declineb, c | Mixed | Y | 71 % | |||

| Koval 1998 [51]g | ADL level | Community | Y | 59 % | 71 % | 73 % | |

| Shah 2001 [47]g | ADL level | Community | Y | 70 % | |||

| Norton 2000 [22] | Functional independenced | Mixed | U | 72 % | |||

| Osnes 2004 [25]f | Living at home receiving assistance, assistance received at same frequency | Mixed | U | 49 % | |||

| Living at home without assistance | 45 % | ||||||

| Vergara 2014 [38] | ADL (MBI)b | Mixed | U | 29 % | |||

| Activity – Self-care | |||||||

| Magaziner 2000 [43]a, d | Washing | Community | N | 62 % | 56 % | ||

| Dressing (socks & shoes) | 67 % | 67 % | |||||

| Dressing (pants) | 80 % | 80 % | |||||

| Getting on/off toilet | 36 % | 37 % | |||||

| Activity – Communications | |||||||

| Magaziner 2000 [43] | Using the telephonea, d | Community | N | 78 % | 77 % | ||

| Participation – Composite measures of Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) | |||||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | IADLs without difficultye | NR | N | 55 % | |||

| Koval 1998 [51]g | IADLs | Community | Y | 34 % | 42 % | 48 % | |

| Shah 2001 [47]g | 46 % | ||||||

| Vergara 2014 [38] | IADLsb | Mixed | U | 25 % | |||

| Participation – Domestic life | |||||||

| Magaziner 2000a, d [43] | Housecleaning | Community | N | 38 % | 57 % | ||

| Shopping | 58 % | 59 % | |||||

| Cooking | 76 % | 77 % | |||||

| Handling money | 69 % | 69 % | |||||

| Pitto 1994 [29] | Social function (mix of self and domestic care)b, d | Mixed | 60 % | ||||

| Participation – Community, social and civic life | |||||||

| Magaziner 2000 [43] | Getting places out of walking distancea, d | Community | Y | 47 % | 47 % | ||

| Health condition | |||||||

| Bentler 2009 [14] | Self-reported health statusb | NR | N | 61 % | |||

| Cognition (TICS)b | 56 % | ||||||

| Magaziner 2000 [43] | Taking medicationsa, d | Community | Y | 71 % | |||

| Pitto 1994 [29] | Health statusb, d | Mixed | 64 % | 82 % | |||

aDetermined as 100 % less percentage of survivors newly dependent

bDetermined as 100 % less the percentage of survivors deteriorated

cIn this study, for patients who had died, functional status in the 2 weeks before death was determined by proxy interview and included

dn/N not confirmed

eDetermined as 100 % less the percentage of survivors that got worse regarding the number of activities with difficulty

f Determined as 100 % less the percentage with loss of walking independence/receiving assistance, participants not followed from inception

g, hStudies from the same cohort

ADL activities of daily living, BOAS Brazil Old Age Schedule, LTC long term care, MBI modified Barthel Index, N no, NR not reported, TICS Telephone Interview to Assess Cognitive Status, U unclear, Y yes

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Data from 10 cohort studies reporting the proportion of people experiencing hip fracture that regain their level of mobility are summarised in Table 4. In general, data from the included cohort studies indicate that 40 to 60 % of surviving patients regain their pre-fracture level of mobility within 1 year (Table 4) [25, 37, 39, 41, 43, 44, 47]. Studies from the US, United Kingdom (UK) and the Netherlands found that amongst those who were independently mobile pre-fracture, 40–44 % of patients recover their pre-fracture mobility independence [25, 37, 41, 47].

Two US population-based studies recorded pre-fracture mobility prospectively (see Additional file 1: Table S2). One found that 53 % of patients had worse mobility 2 years following hip fracture [14]. In this study, the population source had oversampled people 80 years or older and those included were self-respondents at the interview immediately before and after hip fracture. Those that were excluded because of proxy respondents had the worst baseline function. Also, unfortunately, fewer than 80 % of subjects contributed follow-up data in this study. The other study reported that the proportion of survivors able to walk across a room independently decreased from 75 % pre-fracture to 15 % at 6 months [16]. Follow-up for this study was considered adequate, with more than 80 % contributing data.

Outcomes for people living in residential care pre-fracture

Most studies were conducted in populations from the general community or from settings with a minority of people from residential care. Four articles on three cohorts reported functional outcomes for people in residential care [28, 48–50]. Canadian and Australian studies have found that recovery of mobility is lower for those living in residential care than for those living in the community (Table 4; Additional file 1: Table S3) [48, 49]. A large retrospective study of people living in nursing homes in the US reported that, of those who were independently mobile pre-fracture, only 21 % survive and regain their pre-fracture independence at a median of 4 months [28]. This outcome measure differs to those presented in Table 4 for other studies, as the rate indicates a composite of recovery and survival, rather than representing the rate of recovery as a proportion of those surviving. Of those with follow-up data and surviving one year after fracture, 27 % had new total dependence in locomotion (Additional file 1: Table S3) [28].

It should be noted that the pre-fracture mobility of the people in these studies was determined retrospectively, so there is a risk of bias in these data.

Composite measures of basic activities of daily living

Comparisons to a non-fracture group

A Belgian study comparing hip fracture patients to matched controls estimated that 24 % of the loss of independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) 1 year after hip fracture is directly attributable to hip fracture (Table 3) [19]. Other studies indicate that survivors are significantly more likely to be functionally dependent 2 years after fracture (adjusted OR 2.6, 95 % CI 1.7–4.1, p < 0.001) [22] and have more difficulties with activities of daily living [17, 23].

Time to recovery

Two US studies from the same US centre provided estimates of the time to recovery (Additional file 1: Table S4) [42, 43]. Most patients who recover their ability to perform basic ADLs did so within the first 6 months after discharge from hospital, but over the following 6-month period a similar proportion improved or declined (Additional file 1: Table S4) [42]. Time for recovery for different activities ranged from approximately 4 months for upper extremity activities of daily living to 11 months for lower extremity physical ADLs (Additional file 1: Table S4) [43].

Two studies found the proportion of patients recovering their pre-fracture level of ADL increased between 3 and 6 months (Table 4) [50, 51]. However, as these data represent function in survivors, this may indicate longer survival of those better functioning.

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Data from seven cohort studies reporting the proportion of survivors to recover their pre-fracture level of independence for ADLs are summarised in Table 4. Separate studies conducted in the US and Canada estimated that 34 to 59 % of patients regain their pre-level of fracture basic ADL function by 3 months [50, 51] The proportion rises to 42 to 71 % by 6 months [50, 51]. Three separate studies have indicated that approximately 70 % of survivors can recover their pre-fracture level of ability for basic ADLs [22, 47, 51, 52].

Two US population based cohorts found a significant increase in the number of basic ADL limitations for those who had experienced hip fracture compared to older people who had not [17]. Another US population based study found that 51 % of people had deteriorated in terms of basic ADLs after 2 years (Table 3, Additional file 1: Table S2), however follow-up was considered inadequate in these studies [14].

Data from studies reporting composite basic ADL outcomes at multiple time points following hip fracture generally demonstrate that while approximately 60 to 75 % of people are independent in basic ADLs pre-fracture, this decreases to 40 to 60 % post-fracture (Additional file 1: Table S1). A Norwegian study reported that half of all patients who were living at home before and after hip-fracture, but not receiving assistance pre-fracture, were receiving assistance 1 year after fracture [25]. For those living at home with assistance before and after fracture, half received assistance at the same frequency after fracture (Table 4) [25]. This study did not follow participants from recruitment but surveyed survivors retrospectively using a questionnaire, there is a high risk of bias in these data as a greater proportion of non-responders were discharged to nursing homes.

Outcomes for people living in residential care pre-fracture

Two studies from Canada and Australia indicate that those living in long-term care before a fracture have a poorer recovery than those living in the community (Table 4, Additional file 1: Table S3) [48, 49]. At 6 months post-fracture, a greater proportion of those living in the community before the fracture recovered their pre-fracture function, in comparison to those living in long term care (Table 4p < 0.001) [48]. The adjusted reduction in pre-fracture function at 6 months was 33 % (95 % CI −40.6 to −27.2) for those in long-term care, and 12 % (95 % CI −14.8 to −8.4) for those community dwelling before the fracture [48]. It should be noted that the pre-fracture mobility of the people in all of these studies was determined retrospectively, so there is a risk of bias in these data.

Self-care

Comparison to a non-fracture group

Three studies have reported that fewer people who sustained a hip fracture were independent in self-care outcomes of dressing and grooming in comparison to a non-fracture cohort (Table 3).[16, 21, 23] Magaziner et al. [21] estimated that 2 years following hip fracture, six additional people are disabled in personal grooming, per 100 hip fractures, in comparison to a non-fracture control group.

A US study found a significantly greater proportion of people experiencing hip fracture had difficultly putting on socks 1 to 5 years following hip fracture, in comparison to those without a fracture (Table 3) [23]. However, there is uncertainty in these findings, as the control participants were not matched, the participants were not followed from inception and it is unclear whether follow-up was adequate.

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Magaziner et al. [43] found that of patients who were independent in performing various self-care activities (including washing and dressing) before hip fracture, approximately 20 to 65 % require assistance to do these tasks 1 and 2 years following the fracture (Table 4). In a small Italian study, 40 % experienced deterioration in a measure of level of dependence in both personal and domestic needs 6 months post-fracture (Table 4) [29].

One population-based study that recorded pre-fracture ability prospectively found that while 86 % of people could dress independently before the fracture, only 49 % were independent with dressing at 6 months (Additional file 1: Table S2) [15]. A similar decrease in independence was seen in the subgroup of hip fracture patients that could perform four of five activities independently before the fracture (99 % independent dressing at baseline versus 60 % at 6 months, Additional file 1: Table S2).

Cohorts from Sweden, Japan, Canada and the US in which all or most people were living in the community indicated that 70 % or more of hip fracture survivors were independent in dressing outcomes beyond 4 months post-fracture [31, 34, 48], with rates staying similar up to 10 years post-fracture in a small community living cohort (Additional file 1: Table S1) [31]. This was consistent with outcomes from a Thai study population with a high degree of independence pre-fracture (Additional file 1: Table S5) [26]. A large, retrospective cohort study of data from 18 hospitals in China reported that approximately 60 % of women experiencing a fracture from low impact trauma were independent in self-care a median of 2.6 years after the fracture (Additional file 1: Table S5). Data on the level of independence before the fracture were not available [12].

Outcomes for people living in residential care pre-fracture

A Canadian study conducted in patients from mixed settings reported that approximately 60 % of patients overall were independent with dressing at 6 months post-fracture, compared with 74 % pre-fracture [48]. This represented 73 % independent for those living in the community before the fracture, and 9 % for those living in long-term care; 75 % of patients in the study were from the community (Additional file 1: Table S3) [48].

Participation outcomes

Composite measures of instrumental activities of daily living

Comparison to a non-fracture group

In the US Longitudinal study of Ageing, there was a statistically significant increase in the mean number of advanced ADL limitations in hip fracture patients over the first two postoperative years, in comparison to older adults who did not experience a hip fracture (Table 3) [17].

Time to recovery

A study of hip fracture patients from the US in the 1980s found that most patients who recover their ability to perform IADL do so within the first 6 months [42]. The proportion who were fully independent was greater at 6 months post-discharge than at 2 months post-discharge (Additional file 1: Table S1) [42]. Over the following 6-month period, approximately 20 % of patients improved further while a similar proportion declined to the same degree (Additional file 1: Table S4) [42].

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Two US studies indicated that approximately half of all patients have recovered their pre-fracture independence in terms of IADL 1 or 2 years following fracture (Table 4) [14, 47]. In a US community living cohort, 34 % of people were fully independent in IADL at pre-fracture baseline; this declined to 14 % after 1 year [42]. However Spanish data indicated that only 25 % had recovered at 6 months post-fracture (75 % had deteriorated, deterioration was defined as a score of less than 5 points or a decrease of 2 points on the Lawton IADL scale) [38]. Pre-fracture ability was determined retrospectively in these studies, so there is a risk of bias in these data.

Domestic life

Comparison to a non-fracture group

One study provided data on domestic participation for people experiencing hip fracture in comparison to a non-fracture group. The Longitudinal Study of Ageing reported a statistically significant increase in the number of household ADL limitations experienced by older Americans who had had a hip fracture, in comparison to the remainder of the cohort (Table 3) [17].

Time to recovery

Two studies reported participation in domestic life at more than one time point following hip fracture [31, 43]. A small Swedish study of community living people found that while the proportion of people who participated in domestic life was reduced 4 months following hip fracture; participation remained at approximately the same level for those alive 10 years after their fracture (Additional file 1: Table S1) [31]. Approximately one third of people had the need for social services after fracture; this proportion remained similar from 4 months to 10 years after fracture (Additional file 1: Table S1) [31]. The US study reported similar rates of dependence 1 and 2 years post-fracture [43].

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Magaziner et al. [43] reported that in a cohort of patients living in the community pre-fracture, approximately 20 to 60 % of patients were dependent on others for performance of various domestic activities 1 year after fracture (Additional file 1: Table S1). In a large UK cohort, participation in shopping decreased from 54 % pre-fracture to 33 % of survivors after 1 year [41].

Community, social and civic life

Recovery of pre-fracture function

Four studies from two centres reported data on participation in community or social life after hip fracture [31, 32, 40, 43]. No studies were identified reporting on participation in civic life (eg. voting). A US cohort found that 1 and 2 years after hip fracture, 53 % of those independent pre-fracture required assistance to access, or could not get to, places out of walking distance (Table 4) [43].

In terms of social participation, another cohort from the same region (Baltimore, USA) found that on average, social participation after 6 months for those who fell once or less was similar to that before their fracture, but was reduced in those experiencing two or more falls (Additional file 1: Table S1) [40]. Swedish studies found that for hip fracture patients who were living in their own home pre-fracture, the proportion of people that visited someone in the last month was similar both before, 4 months, 5 and 10 years after fracture (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S5) [32].

Health condition

Comparison to a non-fracture group

A Belgian study reported that the degree of dependence and of cognitive impairment was significantly worse for women 1 year after hip fracture than for women who had not experienced fracture (Table 3) [19].

Time to recovery

Magaziner et al. [43] reported that the recovery time for cognitive impairment following the hospital stay was 4.4 months.

Recovery of pre-fracture health status

Three cohort studies reported medium- to long-term health condition outcomes following hip fracture. A US population-based longitudinal study recording health status prospectively before fracture reported that 2 years following fracture nearly half of patients experiencing hip fracture reported a decline in their health status or cognition (Table 4) [14]. It should be noted that the population source for this study had oversampling of people 80 years or older [14].

Magaziner et al. [29] reported that 1 and 2 years after hip fracture, almost 30 % of those taking medications independently pre-fracture required assistance to do so (Table 4) [43]. A small Italian cohort of patients treated with Ender nailing found that approximately one third of patients reported a deterioration in their health status 6 months after fracture; 5 years after fracture this was approximately one fifth (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Accommodation

Comparison to a non-fracture group

Two studies from different countries have reported an increased risk of institutionalisation in the year post-fracture for people experiencing hip fracture in comparison to controls (Table 3; Belgian study RR for survivors 5.6, 95 % CI 2.0–15.6 [18]; Australian study HR 4.0, 95 % CI 1.7–9.5 risk adjusted for multiple health-related factors [20]).

Recovery of pre-fracture status

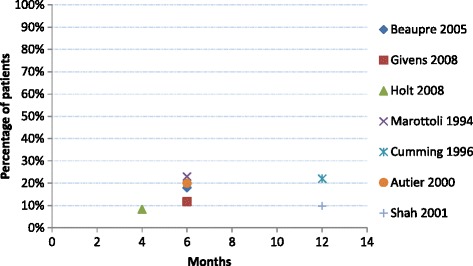

In many industrialised Western nations (Canada, USA, Scotland, Australia, Belgium, Netherlands), approximately 10 to 20 % of people with hip fracture are newly institutionalised by six to 12 months following hip fracture (Fig. 1) [15, 18, 20, 25, 47, 50, 52]. Three studies reported accommodation outcomes for hip fracture patients at multiple time points post fracture (Additional file 1: Table S1). A small Swedish study reported approximately 80 % of survivors remained living in their own homes 4 months after hip fracture, and this proportion remained relatively constant for 10 years [31]. A study conducted in Japan found the proportion of patients living in residential care was similar before and after fracture (5 %, 7 % and 7 % living in residential care before, 1 year and 2 years post-fracture) [34]. This trend extended out to 10 years post-fracture [35].

Fig. 1.

Percentage of surviving patients newly residing in nursing homes in the period following hip fracture, as reported in cohort studies. NB. Shah 2001 is for ambulatory, community dwelling participants pre-fracture; Holt 2008 represents 2 cohorts aged 75–89 and ≥95 years

Quality of life

Comparison to a non-fracture group

Two separate studies have found significant lower quality of life of people who have experienced hip fracture in comparison to control participants, over the longer term (Table 3) [19, 23].

Recovery of pre-fracture function

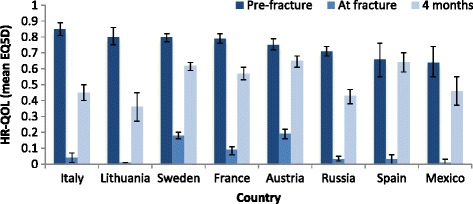

An international study (the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study, ICUROS) demonstrated that quality of life in people 50 years or over sustaining a fracture from low energy trauma decreased significantly after 4 months in all of the eight countries (Fig. 2) [33]. The cumulative quality of life (EQ5D) loss ranged from 0.11 in Austria and Spain (95 % CI 0.10–0.12 and 0.07–0.14, respectively) to 0.21 (95 % CI 0.19–0.22) in Lithuania and 0.20 in Italy (95 % CI 0.19–0.21). Data from the UK and Sweden indicated a quality of life loss of 0.22 over the first year post-fracture (mean difference EQ5D −0.22, 95 % CI 0.17–0.26, UK data [46]; 0.22, 95 % CI 0.20–0.25, average annual loss over first 12 months post-fracture, Swedish data [36]).

Fig. 2.

Health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) as measured by EQ5D before, after and at 4 months following hip fracture. Source: Borgstrom et al. [33]. NB. pre-fracture QOL was determined retrospectively

Discussion

The current review provides clear evidence that people recovering from hip fracture experience ongoing limitations in mobility, basic activities of daily living, self-care, participation and quality of life. Between 40 and 60 % of hip fracture survivors are likely to recover their pre-fracture level of mobility [25, 37, 47]. Up to 70 % of people may regain their pre-fracture level of independence for composite measures of basic ADL [22, 48, 51], but this proportion is likely to be lower for those with higher levels of dependence pre-fracture [48]. Half or fewer people experiencing hip fracture may regain their pre-fracture level of independence in IADLs as determined by composite measures [14, 38, 47]. For those highly independent pre-fracture, more than 70 % may recover their self-care independence for particular ADL activities (eg. putting on pants, cooking) [43]. Most people who recover their ability to perform basic or instrumental ADLs do so within the first 6 months after discharge, although the time to recovery for individual ADLs ranges from approximately 4 to 11 months [42, 43]. The limited data available indicate that participation in domestic life is greatly decreased after hip fracture and that it remains at a relatively constant level, in terms of proportion of survivors, from 4 months post-fracture [31, 43]. Few studies were identified that provided information on participation in community, social or civic life over the longer term for people experiencing hip fracture. Studies in many countries world-wide have indicated that hip fracture has a significant impact on quality of life in the medium- to longer-term. The impact of hip fracture on accommodation is likely to be dependent upon cultural factors. In Western nations, between 10 and 20 % of hip fracture patients are institutionalised within 6 to 12 months post-fracture.

Most identified studies were of community-dwelling individuals or mixed cohorts with a minority of people from residential care settings. Studies that directly compared those living in nursing homes with those from the community have reported much lower recovery rates for mobility, basic activities of daily living and self-care for those from residential care [48, 49]. A large US series of people from residential care, including 12 % who did not receive surgical intervention, reported that only 21 % of people living in residential care both survive and recover their mobility [28]. Similarly, less than 20 % survive and recover their independence for various activities of daily living. Differences in outcomes may be due to different levels of pre-fracture function or to different intervention approaches and intensities. However, it is difficult to directly compare the data from this study to those reported in other cohorts as the proportions are not determined as the percentage of survivors as reported in the other studies and the cohort includes data from those who did not receive surgical intervention [28].

Quantifying the degree of disability in this review over the medium to long-term was difficult due to the wide variations between the identified studies. Many patient and treatment level characteristics are expected to vary between studies, due to different inclusion criteria for the cohorts, including different age criteria, community or mixed residential settings pre-fracture and whether or not a series only includes those receiving surgical management. However, interpretation was further hampered by inconsistent methods of measuring and reporting outcomes. For example, a variety of definitions and methods of measurement for mobility were used, including walking different distances, walking with or without aids, walking indoors or outdoors and various combinations of these (see Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S3). Outcomes were also reported as change from pre-fracture function as either an improvement or decline or as absolute rates of independence or disability for different functions at various follow-up times, or even by the mean scores on the scales used. Future studies should attempt to measure the proportion of patients that regain their pre-fracture level of function or participation to enable comparisons of outcome rates across different study populations and settings. For example, two separate studies conducted in Canada and Australia reported outcomes for hip fracture patients admitted from long term care in comparison to those from the community [48, 49]. The estimate of the proportion walking independently without an aid pre-fracture varied widely between these studies, being 61 % for those from the community in the Canadian study and 96 % in the Australian study. Despite the large differences in function between the study populations at baseline, the proportion recovering is quite similar; the Canadian study reported that 71 % of those in the community recovered their level of pre-fracture function as measured by the MBI and the Australian study found 69 % recovered their prior level of ambulation. In addition, some studies did not clearly report the loss to follow-up of participants for each outcome; adherence to STROBE reporting guidelines would enable more accurate estimates of the range of likely recovery rates to better inform patients and clinicians alike.

Whilst previous reviews have summarised the impact of particular interventions to improve outcomes, [53, 54] or summarised particular outcomes for hip fracture patients, [54, 55] to the authors knowledge this is the first review to attempt to comprehensively summarise the medium to long term disability outcomes for hip fracture patients. This summary will enable clinicians and policy makers to gain an overview of likely outcomes and impacts of hip fracture for patients. In addition, summarising the outcomes for hip fracture according to the current WHO ICF Framework enables readers to understand outcomes from the perspectives of both the person and the person in society. The current review is not without limitations. This review was not conducted systematically and therefore cannot be assumed to be a completely comprehensive review of all studies. However, it provides a comprehensive overview of outcomes according to the ICF framework and includes the key studies reporting extensive information on functional recovery following hip fracture. The authors are unaware of any other reviews providing a similar summary of long-term disability outcomes after hip fracture. No studies were identified from Africa and only a few included from South East Asia or South America. We did not attempt to analyse findings by gender, although most studies included more than three quarters women and it is known that mortality rates are higher for men than women [45, 56, 57]. Pooling of study outcomes was not performed due to the wide variation in the type and reporting of outcomes used. This review did not examine predictors or risk factors for recovery or ongoing loss of mobility, function, life participation or changes in accommodation.

Most of the studies that report on disability outcomes are limited to those who survive to the specified outcome time point. Thus, this report is on the disabling effects of hip fracture on those who survive. However, it is important to consider that as many as 47 % may have died prior to 1 year, depending on the population being studied [28, 35, 58, 59]. Mortality rates for the included studies for the first 12 months post-fracture were generally approximately 10–20 %. Mortality in a series of patients from Brazil was reported as 35 %; in this series the median time between fracture to surgery was 9.5 days (interquartile range 6 to 17 days) [39]. A study of more than 60, 000 people experiencing hip fracture in residential care reported mortality rates of 36 % at a median of 4 months and 47 % died within 1 year [28]. In addition, it is likely that the least healthy patients are those that are lost to follow-up, therefore the study estimates may contain bias by including data from healthier survivors and are likely to provide an upper estimate of the recovery rates following hip fracture [43].

This report was limited to observational studies that were conducted under the usual care conditions of the study sites. It does not attempt to examine the relative effectiveness of different approaches to care. As the rehabilitation interventions received by study participants are varied these studies tell us about the range of current outcomes rather than potential for improvement with different approaches to intervention. Previous reviews have reported on interventions designed to improve outcomes following hip fracture [54, 60]. While there is much data available on the long-term recovery of mobility and basic ADLs for people experiencing hip fracture, data on the long-term impact on IADLs and life role participation are scarce. There is a need for further research on the consequences of hip fracture to inform policy makers and planners preparing for the increasing numbers of older people with disability resulting from hip fracture likely to be part of our society in the future. There is also a need for consistency in outcome measures to enable comparison and pooling of studies and outcomes across and between regions.

Conclusions

This review highlights that while a proportion of people recover their pre-fracture function following hip fracture, for many the outcome from hip fracture is relatively poor. Future studies should determine the proportion of people that regain their pre-fracture level of functioning or participation to enable comparisons of outcomes between study populations and settings. There is a need to invest in research into interventions and programs designed to improve the longer term functional recovery of people following hip fracture, particularly given the increasing impact this is likely to have on our societies as the population demographics change.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The salary of S. Dyer and part of the salary of M. Crotty were funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Centre on Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People [grant no. GNT9100000]. The salaries of C. Sherrington and I. Cameron are funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowships. L. Beaupre receives salary support from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research as a New Investigator and from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions as a Population Health Investigator. J. Magaziner received funding from National Institutes of Health Grants R37 AG09901 and P30 AG028747. The research was conducted independently from the funding bodies.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are presented in the tables within the manuscript and supplementary materials.

Authors’ contributions

SMD identified and selected studies, conducted data extraction, quality appraisal and manuscript preparation. MC, JM, LAB, IC and CS contributed to the design of the review, identification of studies, data interpretation and manuscript preparation. CS contributed to quality appraisal, NF contributed to data extraction, classification of outcomes and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

MC, JM, LB and IC are authors of studies reporting long term functional outcomes following hip fracture. JM consults with companies that are developing or testing products to improve functional outcomes. The authors declare that they have no financial competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IADL

Instrumental activities of daily living

- ICF

International classification of functioning, disability and health

- OR

Odds ratio

- QALY

Quality adjusted life year

- QOL

Quality of life

- US

United States

- WHO

World Health Organization

Additional file

Outcomes from studies reporting activity, participation and accommodation outcomes at multiple follow-up times after hip fracture. Table S2. Medium to long-term functional outcomes for hip fracture patients in comparison to pre-fracture baseline, from prospective population-based cohort studies. Table S3. Medium to long-term function outcomes for hip fracture patients from studies reporting outcomes for those living in residential care (percentage of survivors). Table S4. Additional data on time to recovery of function following hip fracture as estimated from cohort studies. Table S5. Participation outcomes at single time-points post-fracture for countries or outcomes otherwise poorly represented. (PDF 348 kb)

Contributor Information

Suzanne M. Dyer, Phone: + 8 8275 1103, Email: Suzanne.Dyer@sa.gov.au

Maria Crotty, Email: Maria.Crotty@sa.gov.au.

Nicola Fairhall, Email: nfairhall@georgeinstitute.org.au.

Jay Magaziner, Email: jmagazin@epi.umaryland.edu.

Lauren A. Beaupre, Email: Lauren.Beaupre@ualberta.ca

Ian D. Cameron, Email: ian.cameron@sydney.edu.au

Catherine Sherrington, Email: csherrington@georgeinstitute.org.au.

References

- 1.Global Health and Ageing [http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf]. Accessed 1 Apr 2016.

- 2.von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–133. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0014-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization: WHO Global report on falls Prevention in older Age. 2007.

- 4.Mitchell R, Harvey L, Brodaty H, Draper B, Close J: Hip fracture and the influence of dementia on health outcomes and access to hospital-based rehabilitation for older individuals. Disability and rehabilitation. 2016;38(23):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA: World-wide Projections for Hip Fracture. Osteoporosis International. 1997;7(5):407–413. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cauley JACD, Kassem AM, Fuleihan G-H. Geographic and ethnic disparities in osteoporotic fractures. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(6):338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhanwal DK, Dennison EM, Harvey NC, Cooper C. Epidemiology of hip fracture: worldwide geographic variation. Indian J Orthop. 2011;45(1):15–22. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.73656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram M, Norman R, Kemp L, Vos T. Review of the long-term disability associated with hip fractures. Inj Prev. 2011;17(6):365–370. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang O, Hu Y, Gong S, Xue Q, Deng Z, Wang L, Liu H, Tang H, Guo X, Chen J, et al. A survey of outcomes and management of patients post fragility fractures in China. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(11):2631–2640. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World health Organisation: Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. In. Geneva; 2002.

- 14.Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, Cook EA, Wright KB, Geweke JF, Chrischilles EA, Pavlik CE, Wallace RB, Ohsfeldt RL, et al. The aftermath of hip fracture: discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(10):1290–1299. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marottoli RA, Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM., Jr Predictors of mortality and institutionalization after hip fracture: the New Haven EPESE cohort. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(11):1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.11.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marottoli RA, Berkman LF, Cooney LM., Jr Decline in physical function following hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(9):861–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolinsky FD, Fitzgerald JF, Stump TE. The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(3):398–403. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.3.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Autier P, Haentjens P, Bentin J, Baillon JM, Grivegnee AR, Closon MC, Boonen S. Costs induced by hip fractures: a prospective controlled study in Belgium. Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(5):373–380. doi: 10.1007/s001980070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boonen S, Autier P, Barette M, Vanderschueren D, Lips P, Haentjens P. Functional outcome and quality of life following hip fracture in elderly women: a prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(2):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cumming RG, Klineberg R, Katelaris A. Cohort study of risk of institutionalisation after hip fracture. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1996;20(6):579–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1996.tb01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magaziner J, Fredman L, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, Zimmerman S, Orwig DL, Wehren L. Changes in functional status attributable to hip fracture: a comparison of hip fracture patients to community-dwelling aged. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):1023–1031. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton R, Butler M, Robinson E, Lee-Joe T, Campbell AJ. Declines in physical functioning attributable to hip fracture among older people: a follow-up study of case–control participants. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22(8):345–351. doi: 10.1080/096382800296584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosteson AN, Gabriel SE, Grove MR, Moncur MM, Kneeland TS, Melton LJ., 3rd Impact of hip and vertebral fractures on quality-adjusted life years. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(12):1042–1049. doi: 10.1007/s001980170015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morin S, Lix LM, Azimaee M, Metge C, Majumdar SR, Leslie WD. Institutionalization following incident non-traumatic fractures in community-dwelling men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(9):2381–2386. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osnes E, Lofthus K, Meyer C, Falch M, Nordsletten H, Cappelen E, Kristiansen J, Kristiansen A, Kristiansen L, Kristiansen I, et al. Consequences of hip fracture on activities of daily life and residential needs. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(7):567–574. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suriyawongpaisal P, Chariyalertsak S, Wanvarie S. Quality of life and functional status of patients with hip fractures in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003;34(2):427–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong MK, Arjandas, Ching LK, Lim SL, Lo NN. Osteoporotic hip fractures in Singapore--costs and patient’s outcome. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2002;31(1):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Magaziner JS, Passarella MA, Mehta S, Werner RM. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1273–1280. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitto R. The mortality and social prognosis of hip fractures. J of the Société Internationale de Chirurgie Orthopédique et de Traumatologie (SICOT) 1994;18(2):109–113. doi: 10.1007/BF02484420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abimanyi-Ochom J, Watts JJ, Borgstrom F, Nicholson GC, Shore-Lorenti C, Stuart AL, Zhang Y, Iuliano S, Seeman E, Prince R, et al. Changes in quality of life associated with fragility fractures: Australian arm of the International Cost and Utility Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (AusICUROS) Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(6):1781–1790. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3088-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borgquist L, Ceder L, Thorngren KG. Function and social status 10 years after hip fracture. Prospective follow-up of 103 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61(5):404–410. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgquist L, Nordell E, Lindelow G, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG. Outcome after hip fracture in different health care districts. Rehabilitation of 837 consecutive patients in primary care 1986–88. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1991;9(4):244–251. doi: 10.3109/02813439109018527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borgström F, Lekander I, Ivergård M, Ström O, Svedbom A, Alekna V, Bianchi M, Clark P, Curiel M, Dimai H, et al. The International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (ICUROS)—quality of life during the first 4 months after fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(3):811–823. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura S, Hasegawa Y, Suzuki S, Sasaki R, Iwata H, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG. Functional outcome after hip fracture in Japan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:29–36. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuboi M, Hasegawa Y, Suzuki S, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG. Mortality and mobility after hip fracture in Japan: a ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89(4):461–466. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strom O, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, Lidgren L, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Abdon P, Ornstein E, Ceder L, et al. Long-term cost and effect on quality of life of osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):269–280. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vochteloo AJ, Moerman S, Tuinebreijer WE, Maier AB, De Vries MR, Bloem RM, Nelissen RG, Pilot P. More than half of hip fracture patients do not regain mobility in the first postoperative year. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(2):334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vergara I, Vrotsou K, Orive M, Gonzalez N, Garcia S, Quintana JM. Factors related to functional prognosis in elderly patients after accidental hip fractures: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira SR, Puts MT, Portela MC, Sayeg MA. The impact of hip fracture (HF) on the functional status (FS) of older persons in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: results of a prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(1):e28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller RR, Ballew SH, Shardell MD, Hicks GE, Hawkes WG, Resnick B, Magaziner J. Repeat falls and the recovery of social participation in the year post-hip fracture. Age Ageing. 2009;38(5):570–575. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. Br Med J. 1993;307(6914):1248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6914.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR, Kenzora JE. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45(3):M101. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.M101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, Fox KM, Dolan M, Felsenthal G, Kenzora J: Recovery From Hip Fracture in Eight Areas of Function. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A. 2000:M498. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Koval KJ, Aharonoff GB, Rosenberg AD, Bernstein RL, Zuckerman JD. Functional outcome after hip fracture. Eff Gen Versus Reg Anesth Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuelsson B, Hedstrom MI, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Samnegard E, Thorngren KG, Cederholm T, Saaf M, Dalen N. Gender differences and cognitive aspects on functional outcome after hip fracture--a 2 years’ follow-up of 2,134 patients. Age Ageing. 2009;38(6):686–692. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffin XL, Parsons N, Achten J, Fernandez M, Costa ML. Recovery of health-related quality of life in a United Kingdom hip fracture population. The Warwick Hip Trauma Evaluation--a prospective cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(3):372–382. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B3.35738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah MR, Aharonoff GB, Wolinsky P, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Outcome after hip fracture in individuals ninety years of age and older. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(1):34–39. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beaupre LA, Cinats JG, Jones CA, Scharfenberger AV, Johnston DWC, Senthilselvan A, Saunders LD. Does functional recovery in elderly hip fracture patients differ between patients admitted from long-term care and the community? J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(10):1127–1133. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crotty M, Miller M, Whitehead C, Krishnan J, Hearn T. Hip fracture treatments--what happens to patients from residential care? J Qual Clin Pract. 2000;20(4):167–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2000.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beaupre LA, Cinats JG, Senthilselvan A, Scharfenberger A, Johnston DW, Saunders LD. Does standardized rehabilitation and discharge planning improve functional recovery in elderly patients with hip fracture? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12):2231–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koval KJ, Skovron ML, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD. Predictors of functional recovery after hip fracture in the elderly. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Givens JL, Sanft TB, Marcantonio ER. Functional recovery after hip fracture: The combined effects of depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1075–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diong J, Allen N, Sherrington C. Structured exercise improves mobility after hip fracture: a meta-analysis with meta-regression. British journal of sports medicine. 2015;50(6):346–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Handoll HH, Sherrington C, Mak JC. Interventions for improving mobility after hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD001704. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001704.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mak JC, Cameron ID, March LM, National H, Medical Research C. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of hip fractures in older persons: an update. Med J Aust. 2010;192(1):37–41. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soderqvist A, Ekstrom W, Ponzer S, Pettersson H, Cederholm T, Dalen N, Hedstrom M, Tidermark J. Prediction of mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a two-year prospective study of 1,944 patients. Gerontology. 2009;55(5):496–504. doi: 10.1159/000230587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]