Abstract

Research has documented the influence of cultural values, beliefs, and traditional health practices on immigrants’ health care utilization in their host countries. We describe our findings of how Hmong immigrants to the US make decisions about whether and when to use traditional and/or Western health services. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 Hmong adults. We found their decisions depended on whether they classified the illness as spiritual or not and how they evaluated the effectiveness of different treatment options for their illness. Hmong participants’ expectations for effective treatment in traditional or Western health care encounters combined with physical evidence of an illness influenced their decisions and often led them to shift from one type of care to the other. Understanding cultural differences in perceptions of the causes of illnesses and the link between perceived cause and treatment is important to improving care for the Hmong population.

Keywords: Traditional medicine, Hmong, health service utilization

There is increasing evidence that health care utilization is influenced by cultural values, beliefs, and traditional health practices (Chung et al., 2014; Kujawska & Pardo-de-Santayana, 2015; Sackett, Carter, & Stanton, 2014). Researchers have reported that the use of traditional folk medicine or a combination of Western treatment regimens and traditional medicine is common among immigrants (Kraut, 1990). This is particularly true among Asian Americans likely because over one-fourth (29%) of Asian Americans are foreign-born so they have less familiarity with Western medicine and health systems (Gryn & Gambino, 2012).

Asian and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial group in the United States (US; Pew Research Center, 2012). However, Hmong, a sub-group of Asian Americans, are distinct in many ways from other Asian American subgroups. The Hmong people are a large and growing population in the US (Hmong National Development Inc., 2010). According to the 2010 Census, there were 260,073 persons of Hmong origin the US with the largest populations in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin (Hmong National Development Inc., 2010). This population grew 40% between 2000 and 2010 and continues to grow (Hmong National Development Inc., 2010).

There are few published studies regarding the influence of Hmong traditions on the use of Western health services in the US (Fadiman, 1997). Understanding how Hmong people make decisions about who they seek care from—traditional or western providers—would improve our understanding of their needs and our ability to provide culturally appropriate medical services. The purpose of this study was to describe how Hmong people decide when they use traditional healers (Shaman) and when they seek Western medical care.

The Hmong

The Hmong people who migrated to the US lived in mountainous areas of China, and then Laos, for centuries before the Vietnam War. The US Central Intelligence Agency recruited Hmong men living in Laos to fight for the US against the North Vietnamese. In 1975, when Laos and Vietnam were defeated by the North Vietnamese army, the Hmong fled across the border to refugee camps in Thailand (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993). In the late 1970s and 1980s, after years in Thai refugee camps, thousands of Hmong were given refugee status and transported to the US and other countries including; France, Canada, Australia, and Argentina (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993). In China and Laos, the Hmong people lived in relatively isolated, rural mountainous areas and developed a self-sufficient lifestyle based primarily on agriculture. Therefore, most Hmong knew nothing about urban living or Western cultures. Their transition to host countries, including the US, was abrupt and traumatic. The close, extended family networks were often disrupted during resettlement. Because Hmong language was oral, the transition to a culture based on written words contributed significantly to acculturation difficulties, particularly for older Hmong (Lee & Xiong, 2013). While a written version of Hmong has recently been created, it is unfamiliar to older Hmong who had no written language (Duffy, 2007).

Health Beliefs and Practices

Many Hmong believe in traditional medical practices, including animistic folk healing and the healing power of shamans (Culhane-Pera & Xiong, 2003). Spirit illness and soul loss beliefs continue to persist for Hmong living outside their native country (Fadiman, 1997). Temporary soul loss or soul separation is believed to be a factor in the majority of illnesses in Hmong traditional health models. Souls can be separated by accident, by a frightening event, or may be taken by an angered or offended spirit. A shaman is the only healer who can communicate directly with the supernatural spirits responsible for the illness and correct the soul loss (Plotnikoff, Numrich, Wu, Yang, & Xiong, 2002). Shamans also use magic healing to treat physical injuries such as gunshot wound and severe bruising (Helsel, Mochel, & Bauer, 2004). One study reported patients who sought care from a shaman with complaint(s) of biomedical conditions such as stroke, diabetes, urinary tract infection, there were instances, where a shaman concluded that the conditions are not associated with a spiritual problem (Helsel et al., 2004).

Although Hmong traditionally practiced shamanism, some Hmong have integrated Christianity and Western medicine into their medical belief systems and culture. This was due in part to the lack of effectiveness of shamanistic ritual in curing illness (Plotnikoff et al., 2002). For some Hmong, a transition to Christian beliefs influenced their responses to illnesses. In contrast to the traditional practice, Christian Hmong people host prayer sessions at churches to help deal with illness and crises (Tapp, 2011). Despite these practices, some Hmong continue to grapple with the contradictory notions of the soul in Christianity and the soul in traditional religion that could suffer from something like fright illness, an illness where the soul has been frightened by an event.

While western medicine has been integrated into the Hmong people’s conceptual framework of health and health care, it has played a lesser role in Hmong people’s ideas about health than their traditional beliefs. Many Hmong are unfamiliar with Western concepts and terminology related to illness and disease (Fang & Baker, 2013). For example, Hmong people who still practice traditional religion fear autopsies because they believed that the disfigurement of the body may prevent the reincarnation of the soul. Western medicine has been used with some reluctance and ambivalence. To date, no studies have examined the process that Hmong people use to make decisions to about who to seek healthcare from– a Western or traditional health care provider or both. In this work, we used qualitative interview data to explore: (a) how Hmong patients determine who to see first, a western or traditional healer? and (b) what factors influence Hmong patients decision to seek western vs. traditional healer when they have medical health problem.

Methods

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study with 11 Hmong-speaking patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) in the US. This study was a part of a larger study that sought to identify facilitators and barriers to getting preventive cancer screening in our health care system. In these interviews we explored: (1) health care experiences generally; (2) knowledge about cancer; (3) experience with preventive cancer screening; (4) experience with interpreter services; (5) experience with language concordant care (e.g. when the patient receives care in a language they speak); and (6) recommendations for improvement of provision of care among LEP patients. For this paper, we report findings in the “health care experiences” domain. Specifically, we examined Hmong participants’ health care seeking decisions of provider, e.g. traditional versus western healthcare providers because the text had rich enough descriptions about choice of providers. The themes presented in this study were brought up independently by participants; we did not initially probe specifically on this decision making process. The Health Sciences Review Board of the University of the Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public health reviewed and approved the study.

Data Collection

We recruited Hmong participants from a large health care system in Wisconsin, USA. Recruitment strategies included posting language-appropriate flyers in clinics and community centers with large Hmong attendees; mailing letters through primary care clinics to the homes of Hmong participants identified as having LEP; attending Hmong cultural events; and asking participants to refer family and friends to the study. Our bilingual staff conducted telephone eligibility screening for all those who called the line or were referred by family or friends. Individuals were eligible if they: (1) self-identified as not speaking English well or not at all (referred to as having limited English proficiency (LEP; Zong & Batalova, 2015), pg. 1), (2) were a native Hmong speaker, (3) were eligible for preventive cancer screening (women ≥18 and men ≥50), (4) had no previous cancer diagnosis, (5) had visited their primary care provider in the past year, and (6) were willing to participate in one interview in a location of their choice. We recruited and interviewed a total of 11 Hmong participants. All individuals who expressed interest met these criteria and participated in the study. Because we have a focused study with clear structured questions and a homogenous sample, our study participants were able to provide rich information so that we were able to achieve saturation (Morse, 2000) with 11 interviews (Morse, 2015).

All 11 interviews were done in Hmong using a semi-structured interview guide, in participants’ homes by the first author, who is bicultural and bilingual in Hmong as well as trained in qualitative interviewing techniques. She was accompanied by the second co-author and another Hmong investigator. This data collection approach is consistent with the Hmong culture of group-based interaction (Lor & Bowers, 2014). The interviewer began each interview with global questions about health care experiences and then later asked more specific questions about whom participants go to for health related advice. For example, one questions asked was: “When you make a decision about your health, who you consult with or seek information from outside the clinic? And “Who do you consult with and what types of health problems have you consulted about?” We also asked people to describe their health care experiences generally. During this description, all participants talked about how they make decisions and whether they do this individually or as a family. The interviews lasted between 45 and 120 minutes and were audiotaped. Each participant received $50 at the end of the interview.

We then translated all transcripts into English to allow our research group to analyze the data; not all of them were fluent in Hmong. To maximize quality and accuracy, we used the group translation method (Lopez, Figueroa, Connor, & Maliski, 2008). The first author transcribed the audio files verbatim in Hmong. The second author and a bilingual Hmong student reviewed the transcripts and translated them into English, focusing on meaning rather than literal translation (Willis et al., 2010). The fourth author, an adjudicator reviewed the back English translation. When there were disagreements among translations, the researchers, met as a group, referred back to the transcripts, and came to an agreement on the best English translation.

Analysis

We used conventional content analysis to analyze the data (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Through this process, we engaged in an iterative process of coding and categorizing the data to ensure that we achieved saturation across the themes (Morse, 2000). We reached saturation on these topics: (a) classification of illness and (b) effectiveness of treatment option in regards to how Hmong patients determine which provider (e.g. Western vs traditional healer) and the factors that influence these choices. Initially, two coders separately coded the transcripts by first reading through each transcript from beginning to end. Each coder highlighted and wrote notes in the margins of the text identifying key words, phrases and concepts that seemed to capture Hmong participants’ descriptions of health care decisions regarding where to seek advice or assistance for health conditions. For example, when we read, “…us Hmong, if there is sudden pain and we can’t do anything right away … then we will go see the doctor first…,” we coded this statement as ‘pain,’ ‘unknown cause of illness,’ and ‘western provider first’. In this initial stage of coding, two coders read through three transcripts and decided on preliminary codes. The preliminary codes were presented to a larger research group consisted of 8–10 members to reach consensus on codes. Once consensus on naming the codes was reached, the two coders read through all ten transcripts, coded passages using the previously identified codes and added new codes where existing codes did not fit. When coding was completed, the two coders met to organize all the codes into a hierarchical structure of primary (main) and secondary (subcategory) codes. For example, for all the codes listed as ‘pale,’ ‘rosy,’ ‘cheeks,’ and ‘swollen,’ we coded these as ‘physical appearance,’ a sub category of ‘illness classification.’ Next, we met with a larger interdisciplinary research team to discuss our categories ensure that the results were transparent (other readers could review coded and supporting narratives), communicable (categories made sense to readers), and coherent (categories were internally consistent). We used NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software to manage the data (QRS International Pty Ltd., 2012).

Results

Eleven Hmong participated in the study. There were six women and five men. The average age was 55 (ranging from 34 to 70). Nine were publically insured. Two were privately insured. On average, the participants had been in the United States for 20 years (ranging from 8 to 33 years). Nine practiced Shamanism and two practiced Christianity.

All Hmong participants reported that their decisions for utilization of traditional and western health providers were dependent on two factors: (1) classification of illness and (2) perceived effectiveness of treatment options.

Classification of Illness

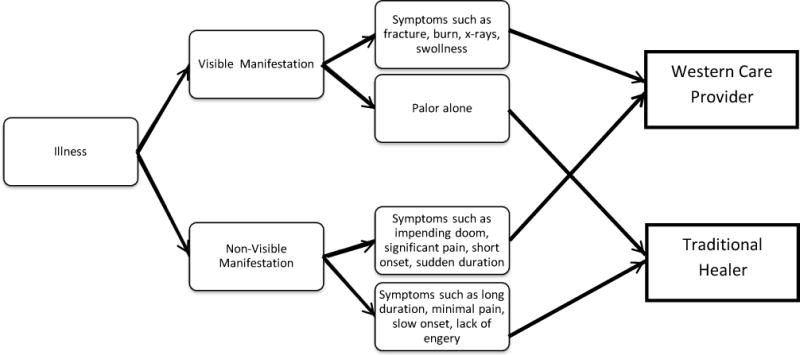

Participants classified illness based on their belief that the illness is spiritual or non-spiritual. This classification determines who Hmong participants seek care from—western or traditional care. Specifically, when considering how to classify their illness and thus who to seek care from, the Hmong participants’ first noted whether or not the symptoms were visible to the naked eye. See figure 1 for the decision-making pathways.

Figure 1.

Hmong Participants’ Conceptualization of Illnesses and its influence on Initial Decision to Seek Western or Traditional Healer

Visible Manifestations

Visible manifestations were symptoms that participants can see, such as; fracture, burn, x-ray, and swollenness. When participants see these visible manifestations, they sought out care from a western care provider first. A few of the participants reported that a physical injury such as a burn or broken limb would lead them to seek a western health care provider first. One participant shared: “I broke both my legs. They took me to this hospital.” (Hmong male 1)

Another visible manifestation of illness was swollenness. A few Hmong participants did not perceive swollenness as having a spiritual cause. In addition, when they did not understand the cause of the swollenness and observed that the swollenness was inside the body then their decision would be to seek a western health care provider. A woman, who had a sister with cervical cancer, described her observation of the swollenness: “…my older sister’s lower stomach, to tell the truth that at that time the lower abdomen is swollen, swollen inside. At that point, where you know that inside and outside is swollen, you know that the uterus is not good.” (Hmong female 3) Consequently, this woman’s sister sought care from a Western health care provider.

However, if the participants observed pallor alone then they sought out a traditional healer first. If a person was pale then it was a sign of an illness. Most often participants perceived paleness as an illness related to soul loss. Thus, participants stated that they would see a traditional healer first to treat it: “When they look at you, you look more pale each day. This is when your spirit is not home…” (Hmong female 5)

Non-Visible Manifestations

Participants’ classifications of non-visible manifestations were based on the nature of the symptom including speed of onset, duration of symptom, severity and perceived precipitator such as spiritual cause. These conditions influenced how Hmong participants made their decision about whether to consult a traditional or western provider. Specifically, three symptoms including pain, fear, and lack of energy were symptoms mentioned that influenced Hmong participants’ decision of who to seek care from first.

Pain

Pain was the most important physical symptoms used by Hmong participants to decide whether they would seek Western or traditional care. Hmong participants focused on the severity of the pain and their ability to identify the perceived precipitator when deciding who to go to for care. For example, all participants reported that if the pain level was perceived as severe, came abruptly, and if they could not make a connection to the cause, or if they felt like they were going to die with the impending doom feeling, then they generally went to a Western doctor first. A participant shared, “I want to tell you guys that when I go [see a Western provider] then it is when I have a lot of pain then I will go.” (Hmong female 5) Another participant shared: “…truthfully, us Hmong, if there is sudden pain… and we don’t know that this illness is too quick then we will go see the doctor first.” (Hmong male 2) Another participant shared the specific level of pain that influenced where she sought care: “… when I have pain around 9 or 10 ok. Then I will go [to a Western doctor]…Nine or ten is when it hurt too much to the point where you feel like you are going to die.” (Hmong female 4)

In the absence of significant pain or if it was ongoing pain, most Hmong participants classified the symptoms they were experiencing as having a spiritual cause. If the cause was spiritual, some Hmong participants described using prayer, herbal remedies, or consulting a shaman first. For example, a participant with ongoing pain described seeing a traditional healer first: “They [Hmong people] say ‘oh, I am sick like this and if I keep on enduring then it’s going to be ok. There’s no need, I can go to a shaman first.’” (Hmong female 1) Another participant described, “…if it is an illness that is slow and not immediate, where your life is not going to end then we do shaman rituals…because it is not a disease, but an illness that is caused by one thing, spirits.” (Hmong male 3)

Lack of Energy & Fear

Hmong participants often classified lack of energy as a symptom linked to spirit loss, soul loss, or fear of evil spirits, and in these situations, they would then seek out the care of a traditional healer first to call the soul or spirit back to the person. The nature of these symptoms included long duration, slow onset of the illness, and lack of energy. Specifically, fear was used to confirm that the symptoms were linked to an event where there is a link to spirit loss, soul loss, or fear of evil spirits. For example, one participant explained what lack of energy [sib sib] meant and its proper course of treatment:

Sib sib for example means that your strength is getting really weak. Like right now, you may still be working, but you are tired and when you walk, you walk slowly. This is when your spirit is not home and is searching for another mom and dad. So then they will do a procedure to call the soul back to the original body [cwb thiab] where they use an egg or if they don’t do the procedure [cwb thiab] then they boil and pour the water at the front door and do a soul calling [hu plig] ritual. (Hmong female 4)

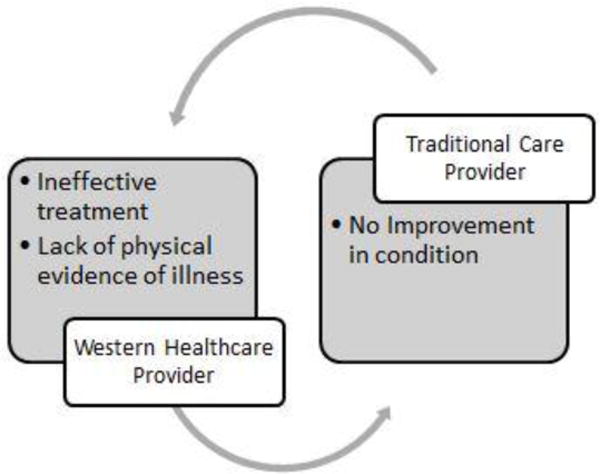

Reconsidering the Cause: Switching the Choice of Provider

Perceptions about effectiveness of treatment options played an important role in deciding when to shift care to a different provider or being open to a different origin of the problem. For example, physical evidence of illness from Western care providers played a role in how Hmong participants thought about the cause of the illness; this influenced them to shift their decisions about who to seek care from. We illustrated this finding in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Switching providers

Effectiveness of treatment option

Ineffective treatment outcomes from traditional or Western care providers lead Hmong participants to rethink the cause of their illness, and as a result, led them to switch care. See figure 2. Participants perceived care to be ineffective when they observed no improvement in their illness; they determined this by evaluating whether or not there had been a change in their symptoms. In other words, if the symptoms persist, participants perceived no improvement in their health; consequently, they switched their care to a different provider. For example, a Hmong woman, who saw a western provider and received medications for her diagnosis, took the medications, but felt that her illness was not improving and decided to switch care to see a shaman and used herbal medicine. She explained:

I have been coughing for three months when I went to get a checkup at the doctor, they use electronic machines to x-ray me. They gave me some pills and some liquid medicine to take. After I took it, I was not any better. I came back and used my Hmong medicine…and I got better. (Hmong female 3)

Similarly, when a traditional healer was the first choice and a ritual was conducted to treat the illness, but the participant did not feel better, the participant then perceived the illness to not be spiritually based; as a result, the participant switched from a traditional healer to a Western health care provider. One participant shared: “If you do a spiritual healing ceremony and if [the person] is not getting better then you have to go to the hospital [to see a Western provider].” (Hmong male 2)

Physical Evidence of Illness

Most participants reported that when a Western care provider was the first choice of treatment and a diagnosis was made, if the provider could not provide a ‘picture’ of the condition/diagnosis, specifically an x-ray then it would lead them to switch over to a traditional healer. An x-ray was discussed as the only source of evidence because it was the only source of representation of their body that they can see and associate with as proof of the illness. For example, a Hmong participant shared that the doctors diagnosed him with gallbladder problems, but could not provide him with a picture to ‘prove’ the diagnosis with the x-ray taken during an emergency room visit.

He then decided to seek care from a shaman afterwards:

I was like “if you guys can’t get it [the x-ray pictures] then let’s wait. If you can’t wait to get the right documents then I refuse.” So then I was mad and they refused and said that if I don’t want to do the surgery then I need to go home…I just went home. Then I went to go do shaman rituals. (Hmong male 3)

Discussion

We found that our Hmong participants held both traditional and Western health beliefs, used both methods and practices of healing, and had complex methods for deciding who to seek care from first and when to change their approach. However, their perceived cause of illness is different from the western perspective of identification and diagnosis of the condition (Brown, 1995). In other words, Hmong participants distinguish causes of illness between physical and spiritual causes. This distinction influenced when our Hmong participants sought Western or traditional medical care. This has implications for communication about health and prevention highlighting the need for a holistic care model that addresses all aspects of health including spiritual and health beliefs among Hmong populations.

Interestingly, in contrast to findings from studies with other Asian groups (Chung et al., 2014; Kujawska & Pardo-de-Santayana, 2015; Sackett et al., 2014), Hmong participants did not describe using Western and traditional practices simultaneously. Yet, their delays in seeking western medical care were similar to those found in other minority groups (Grant, Silver, Bauld, Day, & Warnakulasuriya, 2010; Scott, Grunfeld, Auyeung, & McGurk, 2009). Researchers have documented that one factor that delays care seeking is lack of knowledge (Facione, Miaskowski, Dodd, & Paul, 2002; Rastad, 2012). Previous work has shown that a lack of knowledge and the tendency to attribute symptoms to common illnesses increased delay in seeking care (Rastad, 2012). However, our findings suggest that lack of knowledge is not the primary reason why Hmong participants didn’t initially seek care from a western doctor. Our findings revealed that Hmong participants conceptualize illness differently than western medicine does and thus their interpretation and cultural beliefs of their symptoms facilitated their decision to seek care from a western provider or a traditional healer.

The Hmong in this study believed there were some illnesses that were caused by spirits. This highlights the fact that the best Western medical recommendations may not have the intended impact if it is provided without taking into account the context of Hmong culture. It is essential for providers to understand Hmong patients’ beliefs of illnesses and their perceptions of the causes of illness. Understanding these beliefs can assist health care providers in addressing health information in a culturally sensitive way that is consistent with Hmong patients’ beliefs. For example, providers may want to directly ask Hmong patients if they have used or considered using any other treatments to get a better understanding of how their patients are conceptualizing their illnesses. Additionally, it is important for providers to understand that what they might consider non-compliance, a patient that stops taking their medication, could actually be a patient exploring all of their options. A better understanding of patients’ decision-making process by the health care providers has implications for reducing health disparities among the Hmong.

Hmong speaking patients expressed the desire for physical evidence of their illness. One possible reason for the need for confirmation of illness may be that Hmong people’s health and wellness paradigm is reliant on physical observation of illness. This may in turn be because they have an oral tradition that is based on learning by observation (Lor & Bowers, 2014). They may also seek confirmation because they are distrusting and experience communication barriers in the US health care setting. Studies have reported that communication barriers and lack of trust between general practitioners and patients contributed to delay in care (Akter, Doran, Avila, & Nancarrow, 2014; Ommen, Thuem, Pfaff, & Janssen, 2011). Regardless of the root causes, this finding highlights the need for healthcare providers to be creative in using physical evidence and models to help Hmong patients understand their health diagnoses and conditions. For example, for illnesses that do not have a visual presentation, health care providers could draw diagrams to explain the health information as a form of physical evidence for the Hmong people. Strategies that have been documented to be effective in helping Hmong patients understand health information are utilizing visuals, hands on activities, and videos (Lor & Bowers, 2014).

There were several limitations in this study that should be noted. First, because the larger purpose of this study was to explore factors that contribute to disparities in receipt of preventive cancer screening among Hmong-speaking patients and providers, we were not able to fully capture the temporal nature of Hmong participants’ health care decision making. Prospective, longitudinal studies with Hmong patients could be more informative about how their health care decision-making evolves. This, in turn, would allow for development of an explanatory model to describe their health behavior and ultimately to create culturally sensitive interventions for this population. In addition, with the increasing demands of alternative approaches to health care services, more research should investigate various aspects of traditional health care services and their contributions to the health of Hmong immigrants. Because this study was conducted with Hmong who have a recently visited a primary care provider, these participants may have more orientation to western medicine. More research is needed to examine how Hmong’s decisions about health care differ in other health care settings and across other racial/ethnic minority groups.

Our study was qualitative and was conducted with LEP Hmong within one large healthcare system in one Midwestern city, limiting its generalizability. Future studies could examine differences in geographic location of Hmong participants’ health seeking patterns. It may be possible that their experiences differ from English speaking Hmong patients. Additionally, because the interviews were conducted in Hmong and then analyzed in English it is possible that some of the original meaning may not be captured in English. While we acknowledge this is possible, we don’t think this likely occurred due to our group translation method that focused on meaning rather than on literal translation. Future research could also examine the relationship between length of stay in the US and seeking care from type of providers among Hmong participants. Researchers could also explore in detail other physical evidence illustrations Hmong participants considered trustworthy. While this study only explore the use of Western and traditional care providers, specifically shamans, future studies could explore: (a) choices for other Hmong traditional healers, including herbalists, magical healers (tus ua khawv koob), soul callers, diviners, white face shamans and black faced shamans; (b) choices of seeking Christian healing from ministers or priests; and (c) use of western and Hmong healers concurrently to better understand how each providers play a role in Hmong patients’ decision and treatment options. Because this study was part of a larger study with a different focus, researchers could not follow up with further questions. Future studies could focus on how much contact Hmong patients have with each provider (e.g. traditional healer vs Western healthcare provider) and could further explore the relationship between the physical components of a disease and its physical manifestation from the Hmong patient perspective.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine Hmong people’s decisions about how and when to seek care from traditional healers and/or Western health care providers. Health care providers working with Hmong patients may not understand how cultural practices may influence Hmong patients health care decisions. This study suggests Hmong patients’ decisions about which type of provider they sought care from was dependent partially on how they classified their illness based on their symptoms and physical signs, which indicated to them whether the likely cause of their problem was physical or spiritual, and partially on the beliefs about the effectiveness of the treatment they were receiving from Western and traditional providers. This study has important implications for providers and Western health care. In particular, there needs to be a better understanding of Hmong patients’ health paradigms to ensure we are providing care that addresses their health concerns and meeting the patients’ needs. Health care providers could use these study findings to ensure that they provide health education to the Hmong people in a way that acknowledges their health beliefs and the need for physical evidence of illness and to help educate providers on how Hmong patients attribute causes of illnesses to both physical and spiritual origins.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the willingness of all study participants to speak with the community centers and us for assisting in the recruitment phase of our study. We would like to thank Dr. Barbara Bowers for providing feedback on this manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the University of Wisconsin Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center (UWCCC) for the funds to complete this project. This work is also supported in part by NIH/NCI P30 CA014520- UW Comprehensive Cancer Center Support. Space and technical support was provided by the Health Innovation Program, which is supported, by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Additional funding for this project was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. The first author was also supported by the National Hartford Center of Excellence Patricia Archbold Scholar Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akter S, Doran F, Avila C, Nancarrow S. A qualitative study of staff perspectives of patient non-attendance in a regional primary healthcare setting. The Australasian Medical Journal. 2014;7(5):218–226. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2014.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. Naming and framing: The social construction of diagnosis and illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:34–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung VCH, Ma PHX, Lau CH, Wong SYS, Yeoh EK, Griffiths SM. Views on traditional Chinese medicine amongst Chinese population: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Health Expectations. 2014;17(4):622–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00794.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane-Pera K, Xiong P. Hmong culture: Tradition and change. In: Culhane-Pera K, Vawter D, Xiong P, Babbitt B, Solberg M, editors. Healing by heart: Clinical and ethical case stories of Hmong families and Western providers. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt Univiversity Press; 2003. pp. 11–68. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. Writing from these roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American community. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Facione NC, Miaskowski C, Dodd MJ, Paul SM. The self-reported likelihood of patient delay in breast cancer: new thoughts for early detection. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34(4):397–407. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: A Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang DM, Baker DL. Barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening among women of Hmong origin. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2013;24(2):540–555. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E, Silver K, Bauld L, Day R, Warnakulasuriya S. The experiences of young oral cancer patients in Scotland: Symptom recognition and delays in seeking professional help. British Dental Journal. 2010;208(10):465–471. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryn T, Gambino C. The foreign born from Asia: 2011. American Community Survey Briefs. 2012:1–7. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acsbr11-06.pdf.

- Hamilton-Merritt J. Tragic mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942–1992. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel D, Mochel M, Bauer R. Shamans in a Hmong American community. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(6):933–938. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmong National Development Inc. The state of the Hmong American community 2013. Washington, DC: Authors; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut A. Healers and strangers: Immigrant attitudes toward the physician in America—A relationship in historical perspective. JAMA. 1990;263(13):1807–1811. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.13.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawska M, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Management of medicinally useful plants by European migrants in South America. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;172:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Xiong S. Life of Hmong elders in the New Millennium. Fresno, CA: Fresno State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez GI, Figueroa M, Connor SE, Maliski SL. Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(12):1729–1737. doi: 10.1177/1049732308325857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lor M, Bowers B. Evaluating teaching techniques in the hmong breast and cervical cancer health awareness project. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014;29(2):358–365. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0615-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Data were saturated. Qualitative Health Research. 2015;25(5):587–588. doi: 10.1177/1049732315576699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ommen O, Thuem S, Pfaff H, Janssen C. The relationship between social support, shared decision-making and patient’s trust in doctors: A cross-sectional survey of 2,197 inpatients using the Cologne Patient. International Journal of Public Health. 2011;56(3):319–327. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The rise of Asian Americans. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/

- Plotnikoff GA, Numrich C, Wu C, Yang D, Xiong P. Hmong shamanism. Animist spiritual healing in Minnesota. Minnesota Medicine. 2002;85(6):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QRS International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Version 10) [Computer software] Melbourne, Australia: QRS International Pty Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rastad H. Causes of delay in seeking treatment in patients with breast cancer in Iran: A qualitative content analysis study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(9):4511–4515. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.9.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett K, Carter M, Stanton M. Elders’ use of folk medicine and complementary and alternative therapies: An integrative review with implications for case managers. Professional Case Management. 2014;19(3):113–123. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, Auyeung V, McGurk M. Barriers and triggers to seeking help for potentially malignant oral symptoms: Implications for interventions. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2009;69(1):34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2008.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapp N. The impact of missionary Christianity upon marginalized ethnic minorities: The case of the Hmong. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2011;20(01):70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB, Kudela M, Levin K, Norberg A, Stark DS, Forsyth BH. Evaluation of a multistep survey translation process. In: Hark JA, editor. Survey methods in multinational, multicultural and multiregional contexts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zong J, Batalova J. The limited English proficient population in the United States. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/limited-english-proficient-population-united-states.