Abstract

Heart involvement is the most critical and potentially lethal systemic manifestation in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

We present a case of acute chest pain in a 58-year-old male with severe asthma, which regressed after sublingual administration of nitroglycerine. At the time of hospital admission, there were non-specific ST-changes on the ecg, coronary enzymes were increased, and the patient was concluded to have a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and treated as such.

A subacute cardiac catheterization showed no signs of significant coronary stenosis. During the next days, there was increasing pain and reduced strength in both feet. Paraclinical imaging and neurological examinations could not explain the symptoms, and physiotherapy was initiated. At the time, no connection to patient's diagnosis of severe asthma was made.

The patient was seen in the respiratory outpatient clinic for a routine check-up, three weeks after the initial hospital admission. At this point, there was increasing pain in both legs and the patient had difficulty walking and experienced increasing dyspnea. Blood eosinophils were elevated (12.7 × 109/L), and an acute HRCT scan showed bilateral peribronchial infiltrates with ground glass opacification and small noduli.

A diagnosis of EGPA was established, and administration of systemic glucocorticoids was initiated. A year and a half later, there is still reduced strength and sensory loss.

This case illustrates that it is important to consider alternative diagnoses in patients with atypical symptoms and a low risk profile.

Heart involvement is the most critical and potentially lethal systemic manifestation in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), which makes a quick diagnosis and prompt initiation of correct treatment imperative.

Keywords: Asthma, Acute chest pain, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, EGPA

1. Introduction

EGPA is a vasculitis of the small and medium size arteries. EGPA is associated with severe asthma and eosinophilia in blood and tissue [1]. The diagnostic criteria accordingly to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), is the presence of four or more of these six:

1) Asthma, 2) Greater than ten percent eosinophils on the differential leucocyte count, 3) Mononeuropathy (including multiplex) or polyneuropathy, 4) Migratory or transient pulmonary opacities detected radiographically, 5) paranasal sinus abnormality, 6) Biopsy containing a vessel showing accumulation of eosinophils in extravascular areas [2].

There are great variations in the clinical presentation of EGPA, with cardiac involvement within about one third of the patients [3] and the clinical presentation also varies according to ANCA status with higher frequency of cardial involvement in patients with ANCA negative status [4].

Here, we will discuss the importance of considering a diagnosis of EGPA in patient with previously known asthma who develops chest pain. Specifically, the presence of symptoms from more than one organ system should lead the thought to a systemic disease such as EGPA, being rare but serious.

2. Case presentation

Sudden chest pain developed in a 56-year old male, ex-smoker with 15 pack years, normal BMI, and very physically active, performing triathlon and cycling 40 km per day.

There was no previous history of heart disease, but two years earlier the patient was diagnosed with asthma, with symptoms related to exercise.

The asthma was highly unstable and difficult to treat, with over 6 asthma exacerbations per year, requiring frequent courses of oral prednisone. The anti-asthmatic treatment included high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta-2-agonist, long-acting anticholinergic, theophylline and montelukast.

Despite a daily dose of 15 mg prednisone daily for a period, the patient continued to have many exacerbations. The exacerbations receded after omalizumab was commenced. Prior to the admission there was no worsening of the asthma symptoms.

The chest pain lasted for hours, and the patient described a difficulty of reaching his standard max pulse during exercise the days before. At admission, the respiration frequency was 13, heart rate 60, blood pressure 110/70 and the saturation was 97% without oxygen supplement. Auscultation examination was normal.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, heart rate of 55 and no significant signs of infarction, but there was hammock-like ST changes in the antero-lateral leads. There was a cardial troponin I elevation up to 25800 ng/L and creatine kinase MB elevation up to 96.7 μg/L, and an eosinophil count of 3.57 × 109/L, C-Reactive protein (CRP) 8.

Echocardiography (ECCO) showed normal ejection fraction and a computed axial tomography scan (CT) scan of the heart was also normal.

It was suspected that the patient had a non ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and after administration of sublingual nitroglycerin, the pain regressed. Cardiac catheterization showed a non-significant stenosis, too small for intervention.

The subsequent day, the patient developed pain in the right groin, at the site where he had been catheterized. A hematoma with a diameter of 5 × 10 cm was found on ultrasound, and interpreted to be the cause of the pain. Later, in addition to the pain, the patient described decreased sensibility and strength of the right foot.

Ultrasound of the right groin showed edema, no sign of pseudo aneurism, and again, normal echocardiography.

On day five, the patient experienced that the left foot suddenly gave way under him. A neurologic exam showed decreased sensibility laterally on the left leg, and he was unable to walk on toes and heels. Because of the pain and decreased sensibility and strength, a CT of the abdomen and a Magnetic resonance scan (MRI) of the columna was performed. The CT scan showed no sign of retroperitoneal bleeding and the MRI scan showed slight protrusion of the discus on level L4/L5, otherwise normal. Electromyography was normal, and the assessment by the neurologist was that the symptoms was of non-organic origin (functional).

The patient was then referred for physiotherapy and he was released from the hospital on aspirin, brilique and simvastatin.

On day twenty-two, the patient came for a planned routine check-up at the outpatient clinic at the department of respiratory medicine. At this point, bilateral loss of strength was pronounced and he was mobilized on crutches, and experienced progressive sensory loss and dysesthesia in both legs, now with a stocking distribution.

When examined, he was found to be short of breath, the temperature was 38.4° Celsius, and there was right sided peroneal paresis.

His eosinophil count was 12.7 × 109/L, antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibodies (ANCA) was negative, the total white blood cell count was 18.8 × 109/L and CRP 48 mg/L.

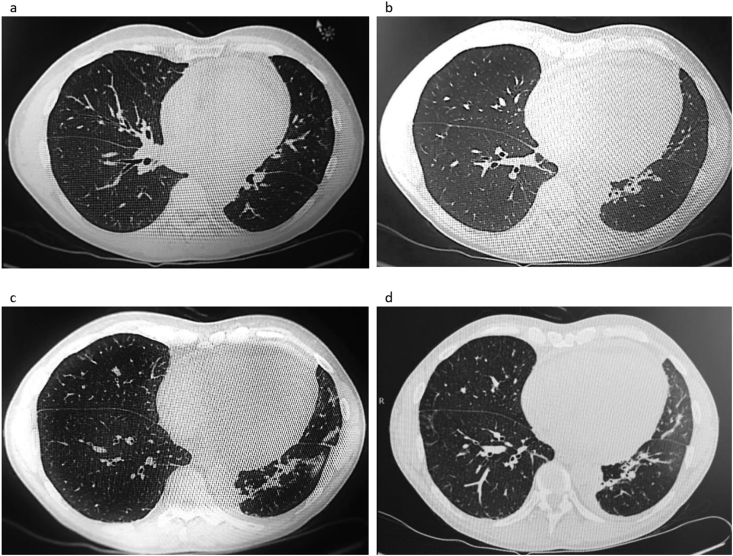

An acute high resolution CT scan (HRCT, Fig. 1) of the lungs was performed, and showed peribronchial consolidated infiltrates and areas with subpleural ground glass attenuation in the right lower lobe (1d). Bilaterally there were small nodules. Compared to the previous CT scan of the heart, there was now an increased size of the heart, and pericardial effusion. ECCO showed thickening of the myocardium, pericardial effusion (5mm), and estimated ejection fraction of 40%. There was a slightly increase of troponin and creatin kinase MB. There was no sign of arrhythmia.

Fig. 1.

High Resolution Computed axial Tomography scan showed peribronchial consolidated infiltrates bilaterally as well as small nodules (1a–c) and areas with subpleural ground glass attenuation in the right lower lobe (1d). Compared to the previous CT scan of the heart, there was now an increased size of the heart, and pericardial effusion.

The patient was admitted to a tertiary lung and cardiology department, on suspicion of pericarditis or endocarditis, and immunosuppressive therapy was started immediately (see below).

The diagnosis of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly known as Churg-Strauss) was made on the basis of the combination of cardial involvement, lung affection, and the presence of polyneuropathy, and highly elevated eosinophils, on a background of severe asthma.

3. Differential diagnosis

At the initial admission, the chest pain which regressed after administration of nitroglycerine, and the coronary enzyme elevation, as well as the small stenosis on heart catheterization could be explained as NSTEMI. However, the stenosis was insignificant, the CT of the heart was normal and the patient developed neurological symptoms shortly after admission. The hematoma in the hours after heart catheterization could initially explain the dysesthesia, but the increase and the loss of strength in addition, and the dissemination to the left foot as well, were not likely to be caused by the hematoma. The insignificant protrusion of discs seen on the MRI could not explain the neurological symptoms, and especially combined with the cardial involvement. Since no biopsy could verify vasculitis, and no paraclinical examination could explain the symptoms, it was considered that they could be of non-organic origin. A contact to the asthma specialist who followed the patient or a MRI scan of the heart might have given the diagnosis earlier.

The frequent treatment with prednisone could have masked eventual previous neurological symptoms and maybe even chest pain.

The treatment with omalizumab could have caused the angina and the later thrombosis, as this is reported as side effects [5]. But it seems unlikely that omalizumab alone could have caused both the pericardial effusion, the high eosinophil count, and the neurological symptoms.

4. Treatment

High dose methylprednisone was initiated in a dose of 1 g three times a day for the first three days. On day two, 800 mg of cyclophosphamide was added. After the first three days, the prednisone dose was run down to 50 mg per day and further reduced over the next days. The treatment with immunosuppressant was maintained with orally methotrexate once a week for three months, this was then converted to intravenously administered cyclophosphamide once a month, because of persisting peroneal paresis and development of a deep venous thrombosis.

5. Outcome and follow-up

At the end of the high dose methylprednisone, the eosinophil count had normalized and the dysesthesia had regressed. Likewise, the dyspnea disappeared. Within a few days, the TnI level normalized, EF normalized within weeks and the pericardial effusion regressed.

The following weeks, the paresis of the feet improved, but the paresis persisted in the right peroneal nerve. A year and a half later there is still peroneal paresis, but no sign of relapse of EGPA.

6. Discussion

The patient presented here has both asthma, hypereosinophilia, polyneuropathy and migratory infiltrates in both lungs, and thereby meets four out of the six diagnostic criteria listed by the ACR (see “Introduction”). EGPA is a rare vasculitis, and develops especially among patients with asthma and eosinophilia [6]. This vasculitis has both pulmonary and extra pulmonary involvement, and there exists a great span in the clinical presentation with symptoms from the lungs and upper airways (asthma), skin, the cardiovascular system, the peripheral nervous system, the kidneys, the gastrointestinal tract and the musculoskeletal system [4], [6].

Cardial involvement in EGPA is serious and frequent. The most frequent described findings are pericardial effusion and clinical signs of heart failure [3]. ECG changes with ST abnormalities and arrhythmias, MRI with sign of endocarditis and cardiomyopathy, and signs of valve dysfunction and elevated troponins is also described [3]. In the referenced study, all patients with cardial involvement previously had no cardial symptoms. EGPA was associated with high eosinophil count at the time of diagnosis, as was the case presented here.

Cardial symptoms as the presenting symptom of EGPA are described in similar cases [7], [8], [9], with manifestations such as pericardial effusion [7], [8], [9] elevated troponins [8] and reduced left ventricular function and ECG changes with new Q-waves [9].

Only one case was similar to ours, regarding presenting symptoms of angina, with no severe risk factors of heart disease, on a background of late-onset asthma, and with concomitant development of polyneuropathy during admission. However, fever and transient visual disturbances was described prior to admission [10].

Only a minority of EGPA patients are positive for ANCA (14 and 28% [3], [4]). Two studies have suggested that ANCA status among EGPA patients is associated with different organ involvement. ANCA negative status was associated with cardial involvement, as it was the case with the patient presented here. ANCA positive status was more frequent among patients with involvement of the peripheral nerve system, kidney and symptoms from ear, nose and throat [4], [6].

The prognosis of EGPA can be assessed with the five factor score system (FFS), where the presence of each of the following is given 1 point: 1) Cardiac involvement 2) Gastrointestinal involvement 3) Renal insufficiency 4) Proteinuria 5) Central Nervous system involvement [6]. Patients with a FSS from 0 usually achieves remission on systemic glucocorticoid treatment, and when the symptoms are under control, a reduction is recommended. With a FFS ≥1 the typical treatment is a combination of systemic glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide, either once a month or daily. The duration remains controversial. The patient presented was given a combination of systemic glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide.

The subgroup of EGPA patients with negative ANCA status and with cardiomyopathy had the poorest prognosis [4] and the prognosis was also worst for patients with endocarditis [3]. This emphasizes the importance of avoiding delay in the diagnostic process and initiation of treatment.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this case emphasizes the importance of considering other causes of chest pain in a patient with a low risk profile and an atypical presentation. In particular, the development of neurological symptoms simultaneously with cardial symptoms on a background of severe asthma should prompt a suspicion of EGPA.

-

•

Chest pain and TnI elevations in a patient without risk factors for ischemic heart disease should lead to considerations regarding alternative diagnoses.

-

•

In a patient with late-onset eosinophilic asthma, development of extrapulmonary organ manifestations, including symptoms of vasculitis and neuritis, should lead to a suspicion of EGPA.

-

•

Fast and correct diagnosis and initiation of treatment is important to prevent permanent injury, and may prevent lethal outcomes

References

- 1.Groh M., Pagnoux C., Baldini C., Bel E., Bottero P., Cottin V. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA) Consensus Task Force recommendations for evaluation and management. Eur. J. Intern Med. 2015;26:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masi A.T., Hunder G.G., Lie J.T. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis) Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33 doi: 10.1002/art.1780330806. 1094 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann T., Manger B., Schmid M. Cardiac Involvement in churg-strauss syndrome. Medicine. 2009;88:236–243. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181af35a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comarmond C., Pagnoux C., Khellaf M. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group Cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:270–281. doi: 10.1002/art.37721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A.K., Hartzema A. Assessing the association between omalizumab and arteriothrombotic events through spontaneous adverse event reporting. J. Asthma Allergy. 2012;5:1–9. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S29811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sablé-Fourtassou R., Mahr A., Pagnoux C. Antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibodies and the churg-strauss syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;143:632–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg M., Lorenz, Gassler N. Rapid progressive eosinophilic cardiomyopathy in a patient with churg-strauss syndrome (CSS) Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2006;95:289–294. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidhu B., Nanda U., Abbas S. Is this an exacerbation of asthma? a cautionary tale. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ungprasert P., Cheungpasitporn W. Is it acute coronary syndrome or churg-strauss syndrome? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013;31 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.05.005. 270.e5-270.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakuoros N., Bastiaenen R., Kourliouros A., Anderson L. Churg-Strauss presenting as acute coronary syndrome: sometimes it's zebras. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]