Highlights

-

•

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is a rare tumor characterized by the multinodular growth of primitive chondroid cells in an abundant myxoid matrix.

-

•

EMC is categorized as a tumor of uncertain differentiation by the 2002 WHO classification.

-

•

EMC has shown to have the recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(9;22) (q22;q12.2), which leads to the oncogenic fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3.

-

•

EMC usually presents in male patients beyond their fifth decade as a slow growing, palpable mass in the extremities.

-

•

Pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas are extremely rare with only isolated case reports found in the literature.

Keywords: Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, Lung neoplasm, Pulmonary lobectomy, Fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3, Lung cancer

Abstract

Background

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) accounts for the 3% of all soft tissue sarcomas and it's categorized as a tumour of uncertain differentiation. This entity has shown to have the recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(9;22) (q22;q12.2), which leads to the oncogenic fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3. This sarcoma usually presents as a slow growing, palpable mass in the extremities. EMC arising from the lung is extremely infrequent. We report one case of pulmonary extraskeletal mixoid chondrosarcoma and a review of the world literature.

Case report

A 69-year-old male patient presented with intermittent hemoptysis for the last 6 months. A PET/CT scan showed a hypermetabolic solid mass with lobulated borders of approximately 29 × 26 mm in the inferior right lobe. We performed a right thoracotomy with inferior lobectomy and lymphadenectomy of levels VII, VIII, X, and XI levels. The neoplasm was constituted by cords of small cells with small round nucleus and scarce cytoplasm immerse in an abundant myxoid matrix. The immunophenotype was positive for MUM-1, CDK4, MDM2, and showed focal expression for S-100 protein and CD56. The final pathology report revealed a pulmonary extraskeletal mixoid chondrosarcoma. No further surgical interventions or adjuvant therapies were needed.

Conclusion

EMC is an intermediate-grade neoplasm, characterized by a long clinical course with high potential for local recurrence and distant metastasis. Treatment for EMC is surgical and non-surgical treatment is reserved for recurrence or metastatic disease. Pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma is a rare neoplasm with only isolated case reports found in the literature.

1. Introduction

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is a rare tumour of uncertain differentiation first described by Stout and Verner in 1953 [1], [2]. The clinicopathological features of this sarcoma were not described until 1972 by Enzinger and Shiraki [3]. EMC has shown to have the recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(9;22) (q22;q12.2), which leads to the oncogenic fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3 [4]. This chimeric gene activates the transcription of target genes involved in cell proliferation and has been detected in approximately 65% of the cases [5]. Histologically, EMC has a marked phenotypic plasticity that overlaps with mesenchymal malignancies, vague resemblance to human cartilage and an uncertain histiogenesis [6]. Immunohistochemical studies in most EMC are positive for vimentin and focally positive for S100 protein [7]. This sarcoma predominantly affects men beyond their fifth decade and normally does not behave in an aggressive way, nevertheless it has a high rate of local recurrence and distant metastases [5]. The deep thigh is the most common location of EMC, although it can be found in the hands, retroperitoneum, head or neck [7]. An EMC arising from the lung is extremely infrequent and isolated to case reports in the literature [7]. We present a case of pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in a 69-year-old male patient that presented with intermittent hemoptysis. This article includes the information available in the world literature but do to it’s rarity most of this information comes from isolated case reports. This case report follows the CARE criteria [8].

2. Case report

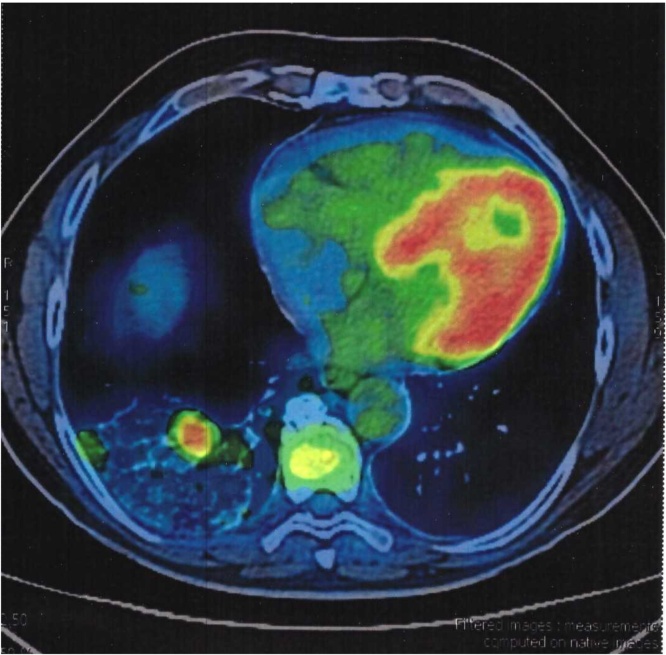

We present a 69-year-old male patient with a past medical history of hypertension. During the last six months, he experienced intermittent hemoptysis without any other symptom. An otolaryngologist explored the patient and initiated treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease. In the last month, the patient presented hemoptysis daily so he decided to get a CT scan of the chest. The chest CT showed a solid, multilobulated mass of approximately 35 mm on its greater axis located in the right lung (inferior lobe). There was no other pertinent history. Physical examination was normal. A PET/CT scan showed a hypermetabolic solid mass with lobulated borders of approximately 29 × 26 mm located in the lateral segment of the inferior right lobe (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PET/CT scan showing a hypermetabolic solid mass located in the lateral segment of the inferior right pulmonary lobe.

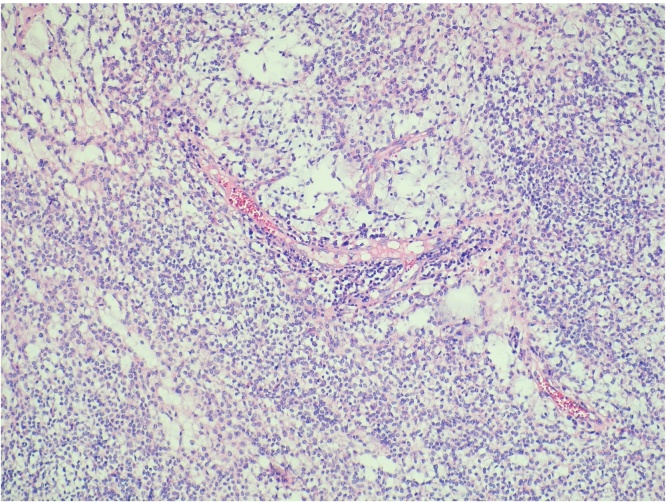

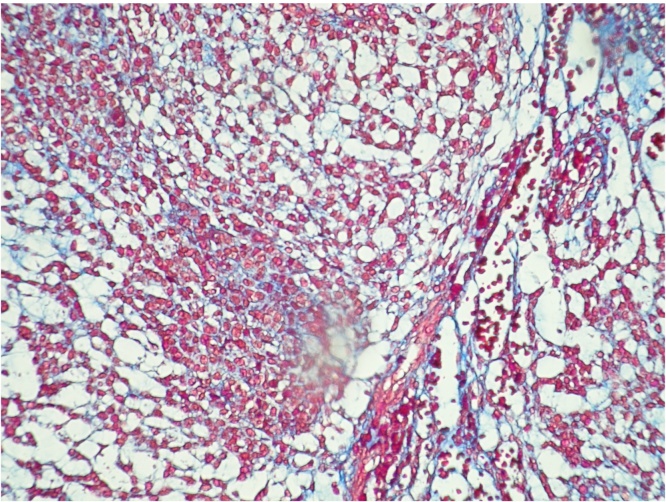

A right thoracotomy with inferior lobectomy and lymphadenectomy of levels VII, VIII, X, and XI levels was performed (Fig. 2). Lymphadenectomy was performed because our preoperative presumptive diagnosis was an adenocarcinoma of the lung. The right inferior lobe was extracted with a tumour of approximately 3 × 3 cm (Fig. 3). The neoplasm was constituted by cords of small cells with small round nucleus and scarce cytoplasm immerse in an abundant myxoid matrix (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). The immunophenotype was positive for MUM-1, CDK4, MDM2, and showed focal expression for S-100 protein and CD56. The surgical margins were negative for malignancy. The final pathology report revealed a pulmonary extraskeletal mixoid chondrosarcoma.

Fig. 2.

Right thoracotomy with inferior pulmonary lobectomy and lymphadenectomy of the VII, VIII, X, and XI levels.

Fig. 3.

Right inferior pulmonary lobe with a mass of approximately 3 × 3 cm.

Fig. 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Fig. 5.

Masson's trichrome staining.

After discussing the case in our multidisciplinary tumour board, no further surgical intervention or adjuvant therapy was recommended. The patient will have a close follow up. There is no evidence of persistent o recurrent disease at six months post-surgery.

3. Discussion

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is a malignant neoplasm characterized by the multinodular growth of primitive chondroid cells in an abundant myxoid matrix [9]. EMC is categorized as a tumour of uncertain differentiation by the 2002 WHO classification and accounts for approximately three percent of all soft tissue sarcomas [2], [4]. EMC is characterized by the presence of various chromosomal translocations that result in abnormal gene products that affect cellular proliferation and differentiation and ultimately lead to tumorigenesis [4]. The typical translocation found in EMC is t(9;22)(q22;q11), which results in the juxtaposition of the gene EWSR1 on chromosome 22 and the gene NR4A3 on chromosome 9 [6]. The fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3 has not been detected in any other type of cancer and seems to constitute a pathognomonic EMC marker [1]. The translocation t(9;22)(q22;q11) is found in approximately 75% of EMC’s cases [10]. Alternative translocations found in EMC are t(9;17)(q22;q11) coding for NR4A3-TAF15 and t(9;15)(q22;q21) coding for NR4A3-TCF12/HTF4 [6]. Immunophenotypically, EMC shows strong vimentin expression, focal S-100 protein expression, and frequently class III β-tubulin and microtubule-associated protein-2 expression, which are known to be restricted to neural cells [5].

The differential diagnosis for EMC include myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue (MEC), myxoid type of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, myxoid liposarcoma, mixed tumour of soft tissue, nodular fasciitis, ganglion cyst, chordoma, myxoid peripheral nerve sheath tumour, and when arising from the lungs primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma (PPMS) [1], [11], [12]. The histological features of EMC partially overlap with PPMS and they occasionally share focal EMA and S-100 expresion [11]. PPMS is characterized by the presence of the chromosomal translocation t(2;22)(q33;q12), which encodes the oncogenic fusion gene EWSR1-CREB1, while EMC is known to express the chimeric gene EWSR1-NR4A3 [11]. MEC and EMC arise predominantly in the proximal lower extremity and it́s difficult to morphologically distinguish them since they both exhibit features typically seen in myoepithelial tumors [12]. MEĆs peak incidence is the fourth decade of life, while EMC frequently arises in the sixth decade [12]. MEC are normally located more superficially than EMC and demonstrate a more aggressive behaviour [12].

The average age of occurrence of EMC is around 50 years and has a male: female ratio of 2: 1 [5], [6], [13]. In Table 1, we state the gender and age preferences of EMC from ten case series published between 2000 and 2014. EMC usually presents as a slow growing palpable mass that causes local pain or tenderness [5]. EMC is located in the lower extremities in approximately 62% of the cases, in the upper extremities in 17% of the cases, and in the abdomen, retroperitoneum, pelvis, or other locations in 21% of the cases [14]. Table 2 presents the location, size, and metastases at time of diagnosis of EMC in ten case series. The majority of EMC has a prolonged clinical course with a 10-year survival rate ranging between 65% and 85%, and a 15-year survival rate of 58%. A 40% risk of distant metastases at 10 years has been documented [15], [16]. On Table 3 we present the clinical follow up of ten EMĆs case series. Despite showing an indolent long term course, EMC has a high potential for local recurrence and distant metastasis and should be considered as an intermediate-grade rather than a low-grade neoplasm [4], [6].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with EMC diagnosis in ten case series.

| Case Series Author | Publication Year | Number of Cases | Male | Female | Mean Age | Age Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oliveira et al. [3] | 2000 | 23 | 11 | 12 | 50 | 22–78 |

| Kawaguchi et al. [9] | 2003 | 42 | 20 | 22 | 52.1 | 21–82 |

| Tateishi et al. [17] | 2006 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 53 | 16–76 |

| Ehara et al. [2] | 2007 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 55.5 | 44–74 |

| Xiu-feng et al. [5] | 2008 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 52.8 | 31–69 |

| Drilon et al. [6] | 2008 | 86 | 57 | 29 | 49.5 | 15–82 |

| Ogura et al. [5] | 2012 | 23 | 10 | 13 | 58 | 35–79 |

| Flucke et al. [11] | 2012 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 57 | 37–82 |

| Stacchiotti et al. [14] | 2013 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 52 | 38–69 |

| Kapoor et al. [13] | 2014 | 13 | 10 | 3 | 54 | 29–73 |

Table 2.

Size, location, and presence of metastatic disease at time of diagnosis of EMC in ten case series.

| Case Series Author | Number |

Size (cm) |

Location |

Metastasis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of Cases | Mean | Range | Lower | Upper | Trunk | Lungs | Other | at Time of Diagnosis | |

| Extremities | Extremities | ||||||||

| Oliveira et al. [3] | 23 | 9.5 | 1.5–18.5 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Kawaguchi et al. [9] | 42 | 7 | 1.5–20 | 28 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Tateishi et al. [17] | 19 | 8.9 | 2–20 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ehara et al. [2] | 4 | NA | NA | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xiu-feng et al. [5] | 9 | 7 | 4–11 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drilon et al. [6] | 86 | 6.8 | 1–30 | 53 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| Ogura et al. [4] | 23 | 7.8 | 3–18 | 14 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Flucke et al. [11] | 5 | 8.5 | 1–15 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Stacchiotti et al. [14] | 11 | NA | NA | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Kapoor et al. [13] | 13 | 9.3 | 3.3–18 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

NA indicates non available.

Table 3.

Clinical follow up of EMC in ten case series.

| Case Series Author | Number of Cases | Clinical Follow Up |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients with Clinical Follow Up | Mean Follow up Period (Months) | Local Recurrences | Metastatic Disease |

Death | |||||

| Patients | Lungs | Bone | Other | ||||||

| Oliveira et al. [3] | 23 | 23 | 111.6 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Kawaguchi et al. [9] | 42 | 42 | 88.8 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Tateishi et al. [17] | 19 | 19 | 61 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Ehara et al. [2] | 4 | 4 | 97.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Xiu-feng et al. [5] | 9 | 7 | 93 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Drilon et al. [6] | 86 | 86 | 43.2 | 27 | 19 | NA | NA | NA | 14 |

| Ogura et al. [4] | 23 | 23 | 109 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Flucke et al. [11] | 5 | 4 | 61 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Stacchiotti et al. [14] | 11 | 10 | 30 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Kapoor et al. [13] | 13 | 12 | 40.5 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

NA indicates non available.

The diagnosis of EMC can be confirmed by demonstrating the presence of the pathognomonic translocation t(9;22)(q22;q11), which results in the fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3 [1], [10]. We reviewed the data from different case series regarding the presence of EWSR1-NR4A3 gene rearrangement and the immunohistochemical findings of EMC and presented it on Table 4. Contrast enhanced CT show primary EMC as isodense to slightly hypodense to muscle with no internal calcifications [14]. On MRI, EMC is characterized by multi-nodular soft-tissue masses with hyper-signal intensity on T2 and heterogeneous enhancement after administration of contrast material [14], [17]. EMC expressing the fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3 show peripheral enhancement on MR more frequently than those with other cytogenetic variants [17]. MRI is preferred over CT for detection of primary disease or local recurrence because of its ability to differentiate the neoplasḿs tissue from unaffected muscle [14].

Table 4.

Presence of ETV6-NTK3 gene rearrangement and immunohistochemical findings of EMC in five case series.

| Case Series Author | Number | EWSR1-NR4A3 | Immunohistochemical Findings |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of Cases | Gene Rearrangement | Vimentin | Synaptophysin | EMA | S-100 | Desmin | NSE | PPAR γ | |

| Oliveira et al. [3] | 23 | NA | 16 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA |

| Tateishi et al. [17] | 19 | 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Xiu-feng et al. [5] | 9 | NA | 9 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 | NA |

| Flucke et al. [11] | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA |

| Stacchiotti et al. [14] | 11 | 11 | NA | 1 | 7 | 3 | NA | NA | 9 |

NA indicates non available.

Surgical intervention is the only satisfactory chance of cure for EMC [6]. The use of radiotherapy for this malignancy has not been well defined but it can be considered in an adjuvant setting or for palliation of metastatic disease [4]. The use of chemotherapeutic agents in the treatment of EMC is controversial and none has demonstrated a durable efficacy [6]. Stacchiotti et al. reported that anthracycline-based chemotherapy is active in a distinct proportion against EMC and can be used in case of advanced and progressive disease [15]. The use of tirosin-kinase inhibitors like Sunitinib may also have a role in the treatment of EMC, nevertheless there is not enough evidence at the time [16]. Table 5 presents the treatments used for EMC in seven case series.

Table 5.

Treatment of EMC in seven case series.

| Case Series Author | Number of Cases | Treatment |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal Excision | Wide Local Excision | Amputation | Radiotherapy | Preoperative Radiotherapy | Postoperative Radiotherapy | Chemotherapy | Preoperative Chemotherapy | Postoperative Chemotherapy | |||||

| Oliveira et al. [3] | 23 | 2 | 17 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Kawaguchi et al. [9] | 42 | 3 | 30 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Tateishi et al. [17] | 19 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Drilon et al. [6] | 86 | 0 | 73 | 0 | 22 | NA | NA | 21 | 21 | 21 | |||

| Ogura et al. [4] | 23 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Flucke et al. [11] | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Stacchiotti et al. [14] | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |||

NA indicates non avaliable.

Pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas are extremely rare with only isolated case reports found in the literature [7]. The lung is the most frequent site of EMĆs metastases [18]. EMC of the lung may present as an asymptomatic mass or with hemoptysis, dyspnea or anemia [18], [19], [20]. The treatment and prognosis regarding EMC of the lung can only be extrapolated from other cartilaginous tumour types because of the lack of good evidence in literature [7]. We found four cases of pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in the literature and presented them in Table 6.

Table 6.

Reported cases of Pulmonary Extraskeletal Myxoid Chondrosarcoma.

| Case Report Author | Publish Year | Age | Gender | Symptoms | Primary Site | Treatment | Follow Up (Months) | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goetz et al. [19] | 1992 | 66 | F | Hemoptysis | Pleura | None | NA | NA | |

| Ichimura et al. [20] | 2004 | 35 | M | None | Lung Parenchyma | Tumor Resection | 75 | Alive | |

| Zhou et al. [18] | 2013 | 51 | F | Severe Anemia | Left Upper Lobe | Lobectomy with Lymph Node Dissection | 32 | Alive | |

| Gadabanahalli et al. [12] | 2015 | 31 | M | Dyspnea | Pulmonary arteries | Tumour excision | 9 | Deceased | |

| Present Case | 2016 | 69 | M | Hemoptysis | Right Lower Lobe | Lobectomy with Lymph Node Dissection | 3 | Alive | |

NA indicates non available.

3. Conclusion

EMC is a tumour of uncertain differentiation first described in 1953 by Stout and Verner. This malignant neoplasm is characterized by the multinodular growth of primitive chondroid cells in an abundant myxoid matrix. This tumor is characterized by the translocation t(9;22)(q22;q11) which encodes for the fusion gene EWSR1-NR4A3. This translocation is pathognomonic for EMC and is present in approximately 75% of the cases. EMC has a predilection for male patients and its peak incidence is in the sixth decade of life. The usual location for EMC is the lower extremities, in 62% of the cases, followed by the upper extremities, abdomen, retroperitoneum, and pelvis. This sarcoma is classified as an intermediate-grade neoplasm and is characterized by a long clinical course with high potential for local recurrence and distant metastasis. Non-surgical treatment for EMC is usually reserved for recurrent or metastatic disease. Pulmonary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma is an extremely rare neoplasm with only isolated case reports found in the literature.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

There was no need for ethical approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Ricardo Balanzá: Data analysis, writing, and study design.

Rodrigo Arrangoiz: Data analysis, writing, and study design.

Manuel Muñoz: Data collection.

Eduardo Moreno: Data collection.

Enrique Luque: Data collection.

Fernando Cordera: Data collection.

Lourdes Molinar: Pathology report.

Nicole Somerville: Writing.

Guarantor

Dr. Rodrigo Arrangoiz.

References

- 1.Bjerkehagen B., Dietrich C., Reed W. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: multimodal diagnosis and identification of a new cytogenetic subgroup characterized by t(9;17) (q22;q11) Virchows Arch. 1999;435:524–530. doi: 10.1007/s004280050437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehara S., Nishida J., Shiraishi H. Skeletal recurrences and metastases of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:823–827. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira A., Sebo T., McGrory J. Extraskeletal Myxoid Chondrosarcoma: A Clinicopathologic Immunohistochemical, and Ploidy Analysis of 23 Cases. Mod. Pathol. 2000;13:900–908. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogura K., Fujiwara T., Beppu Y. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a review of 23 patients treated at a single referral center with long-term follow up. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1379–1386. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiu-feng Y.E., Can M.I., Yu L.I. Clinicopathological features of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: an analysis of 9 cases. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2008;20:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drilon A., Popat S., Bhuchar G. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a retrospective review from 2 referral centers emphasizing long-term- outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2008;113:3364–3371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endicott K., Barak S., Mortman K. A rare case of extraskeletal pulmonary myxoid chondrosarcoma. J. Solid Tumors. 2016;6:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawaguchi S., Wada T., Nagoya S. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a multi-institutional study of 42 cases in Japan. Cancer. 2003;97:1285–1292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyung Y., Chul K., Park S. Primary pulmonary myxoid sarcomas with EWSR1-CREB1 translocation might originate from primitive peribronchial mesenchymal cells undergoing (myo)fibroblastic differentiation. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1645-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flucke U., Tops B., Verdijk M. NR4A3 rearrangement reliably distinguishes between the clinicopathologically overlapping entities myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue and cellular extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gadabanahalli K., Baleval V., Bhat V. Primary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma of pulmonary arteries: a rare mimic of acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Interact Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015;20:565–566. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapoor N., Shinagare A., Jagannathan J. Clinical and radiologic features of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma including initial presentation local recurrence, and metastases. Radiol. Oncol. 2014;48:235–242. doi: 10.2478/raon-2014-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stacchiotti S., Dagrada G., Sanfilippo R. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a retrospective study. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2013 doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacchiotti S., Dagrada G., Morosi C. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: tumor response to sunitinib. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2012 doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eguchi T., Yoshida K., Saito G. Intrathoracic rupture of an extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011;59:367–370. doi: 10.1007/s11748-010-0674-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tateishi U., Hasegawa T., Nojima T. MRI features of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Q., Lu G., Liu A. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in the lung: asymptomatic lung mass with severe anemia. Diagn. Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goetz S., Robinson R., Landas S. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma of the pleura: report of a case clinically simulating mesothelioma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1992;97:498–502. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/97.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichimura H., Endo K., Ishikawa S. Primary chondrosarcoma of the lung recognized as a long-standing solitary nodule prior to resection. Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;53:106–108. doi: 10.1007/s11748-005-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]