Highlights

-

•

The main goal of the treatment is the anatomical reduction of the ulna fracture and the radial head dislocation in acute and chronic Monteggia cases.

-

•

The most commonly preferred technique is open reduction with ulnar osteotomy.

-

•

The radiocapitellar joint is very sensitive to ulna length.

-

•

To decide whether to repair or reconstruct the annular ligament remains controversial.

-

•

Anatomic and stable restoration of radiocapitellar joint by correcting ulna deformity may be performed.

Keywords: Monteggia case report, Fracture-dislocation, Treatment, Posterior interosseous nerve palsy, Ulnar osteotomy, Annular ligament

Abstract

Introduction

The main goal of the treatment is the anatomical reduction of the ulna fracture and the radial head dislocation in acute and chronic Monteggia cases. Acute pediatric Monteggia lesions are generally treated non-surgically; however, the treatment of chronic Monteggia is challenging. The aim of this article is to share our experiences about treatment of neglected Monteggia lesion.

Presentation of case

A 6-year-old girl who underwent a surgery in our clinic for a missed Bado type-III Monteggia fracture-dislocation of the right elbow with concomitant posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) palsy, which resolved spontaneously after the operation. The operation consisted of open reduction of the radial head, transverse ulnar osteotomy and fixation with an intramedullary Kirchner wire, and annular ligament repair without exploring PIN. The patient was seen in routine follow-up periods until the postoperative first year using plain radiographies. At 16th week follow-up, all functions of the PIN were returned. At first-year follow-up, full range of elbow motion was observed; plain radiographies showed radiocapitellar joint congruency, and Mayo Elbow Performance Index was one hundred.

Discussion

Treatment planning for chronic, neglected or missed Monteggia fractures is challenging. There is no consensus about the definitive treatment in the literature.

Conclusion

We recommend anatomic and stable restoration of radiocapitellar joint by correcting ulna deformity. Radiocapitellar fixation and PIN exploration may not be necessary in all neglected Monteggia lesions.

1. Introduction

Monteggia fracture-dislocation was described firstly by Giovanni Monteggia as the fracture of the proximal ulna associated with the anterior dislocation of the radial head in 1814 [1]. Monteggia fracture-dislocations were classified in four groups according to both level and the angulation of the ulna fracture and the direction of the radial head dislocation by Jose Luis Bado. The fracture of the proximal ulna metaphysis and the lateral dislocation of the radial head are classified as Bado type 3 lesions, exactly, as in our case. Approximately 20% of the Monteggia fractures are, type 3 lesions. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy is the most common nerve injury in Monteggia fracture-dislocations [2], [3]. Most of these injuries are neuropraxia and recover slowly after the anatomical reduction of the radial head [4].

The main aim of the treatment is the anatomical reduction of the ulna fracture and the radial head dislocation in both acute and chronic cases. Acute pediatric Monteggia lesions are commonly treated conservatively with closed reduction and casting [8]. Displaced fractures of the ulna, however, should be fixed by an intramedullary nail or plate and screws. The treatment of chronic Monteggia is challenging. There are various surgical techniques, described in the literature, as ulnar osteotomy, the open reduction of the radial head, annular ligament repair or reconstruction, bone grafting, ulna lengthening, or a combination of these [5], [6], [8], [9].

In our case, we report a missed fracture of the proximal ulna diaphysis and the lateral dislocation of the radial head with concomitant PIN palsy, which resolved after surgical treatment. One year postoperatively, we tested pain intensity, motion, stability, and function parameters of the elbow with Mayo Elbow Performance Score, which was excellent with 100 points [7]. The aim of this article is to contribute to the literature sharing our surgery experiences regarding this patient who achieved excellent functional and radiographic outcomes.

2. Presentation of case

A 6-year-old girl applied to our hospital with right elbow pain and restricted motion in her right wrist. We learnt from her parents that she fell down from a swing on her right arm 4 weeks ago. There was no hospital administration after the injury. Four weeks later her parents noticed the weakness in her hand and the restricted motion of her elbow, especially in supination – pronation arc. Physical examination showed proximal forearm tenderness and limited supination. The supination and pronation ranges were 0° and 90°, respectively, with the elbow at 90° of flexion. There was no sign of a vascular injury but she had limited extension of her wrist and fingers in neurologic examination. Sensorial examination was normal, however extensor muscle powers of wrist and fingers were graded 1/5.

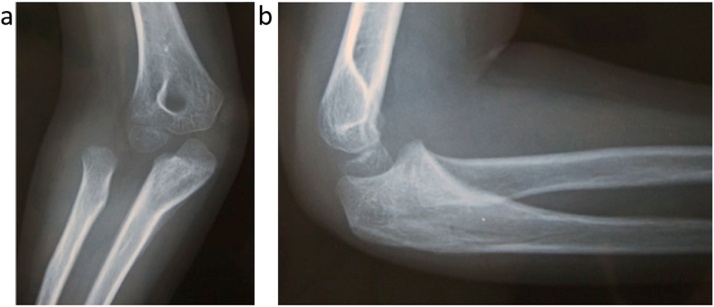

Plain radiologic examination showed a fracture of the proximal ulnar diaphysis and a lateral dislocation of the radial head (Bado type III Monteggia fracture-dislocation) (Fig. 1a, b). In the light of the findings above, we planned open reduction of the radial head, transverse ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament repair without exploring PIN for the patient. This surgery was offered to the family to gain anatomic reduction of elbow structures and improve the arm function. After an informed consent for this treatment plan was obtained from parents of the patient, we performed the operation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative radiographs of the patient during admission to our hospital.

a: antero-posterior radiograph of the right elbow: displays the lateral dislocation of the radial head (Bado type-III lesion).

b: lateral radiograph of the right elbow.

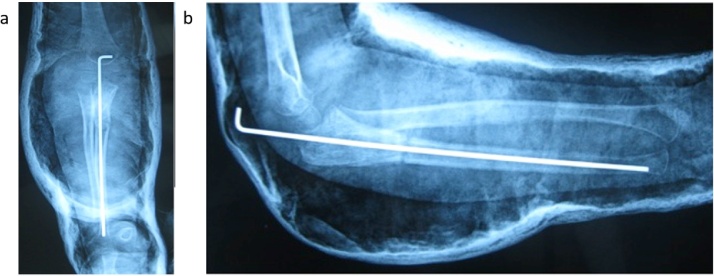

Fig. 2.

a and b Antero-posterior and lateral radiographs of the forearm at 1st day after the operation, displaying radiocapitellar congruency.

We preferred an extensile posterolateral approach (Boyd’s approach) that allows one to combine the ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of the radial head, use of triceps tendon to reconstruct the annular ligament (if need arises) using a single incision. We were aware of an attempt to reduce the radiocapitellar joint is inefficient without a concomitant corrective ulnar osteotomy. Therefore, we firstly performed the transverse ulnar osteotomy at the apex of the deformity, which was fixated with an intramedullary Kirchner wire. We saw that the radial head was not reduced, in spite of the osteotomy. Open reduction of the radial head followed, which was observed as stable during the operation, so that fixation of the radiocapitellar joint was assessed as unnecessary. At the end of the case, rupture of the annular ligament was repaired to improve stability. After the operation, we applied a long arm cast at 90 ° of elbow flexion and forearm full supination. Post-operative congruent radiocapitellar reduction was radiographs were taken weekly to control the radiocapitellar congruency. Afterward long arm cast was removed at the end of the 6th week, the physical examination indicated 0° supination and full pronation. Active elbow range of motion exercises were started immediately. At 8th week of follow-up, PIN started to recover slowly which was evaluated with the degree of forearm supination. Supination was 20°, and total rotation arch of the forearm was 110°. At the 12th week, the intramedullary Kirchner wire was removed when viewing callus formation in plain radiographs. At 16th week follow-up, all of functions of the PIN were returned, and the supination was assessed as around 60°. One year post-operatively, full range of elbow motion in both coronal and sagittal plains was achieved (Fig. 3). Plain radiographies showed that the radiocapitellar joint congruency was achieved (Fig. 4a, b). Mayo Elbow performance Score was excellent with 100 points; the patient could continue her daily life without any limitation.

Fig. 3.

One year post-operatively, full range of elbow motion in both coronal and sagittal plains was achieved.

Fig. 4.

a and b 1 year follow-up antero-posterior and lateral radiographs display the radiocapitellar joint congruency.

3. Discussion

Monteggia fracture-dislocation is a relatively rare injury, accounting for approximately 1% of all fractures of upper limb. In 1814, Giovanni Monteggia admitted two cases of the fracture of the proximal 1/3 of the ulna associated with the anterior radial head dislocation [18]. Later Bado attributed Monteggia lesion to define distinct types of dislocation of the radial head in Monteggia fractures [2]. Bado type I, is the original type, and is the most common type seen in children. While type II defines posterior dislocation of the radial head associated with ulnar metaphyseal fracture, type III represents lateral dislocation of the radial head. Type IV includes both ulnar and radial fractures with accompanying an anterior radial head dislocation [2], [3].

Monteggia fracture-dislocation can be missed in the emergency room if the angulation of the ulna fracture is minimal. Neglected or missed Monteggia fractures are described as cases presenting 4 weeks after the initial trauma [5].

Acute pediatric Monteggia fractures can be managed non-surgically with closed reduction and cast immobilization successfully. However chronic, neglected or missed Monteggia fractures may need various kinds of treatments. Several surgical techniques were described to manage this challenging injury such as ulnar and radial osteotomies, open or closed reduction of the radial head, repair or reconstruction of the annular ligament, temporary fixation of the radial head with a trans-articular wire, bone grafting, ulna lengthening using Ilizarov technique, radial head excision, or combination of these techniques. There is no clear consensus about the most favorable technique [5], [6], [8], [9], [12], [18]. The most commonly preferred technique is open reduction with ulnar osteotomy with or without annular ligament reconstruction in the literature. We preferred open reduction of the radial head, ulnar osteotomy, and repair of annular ligament. Open reduction alone may not be enough to achieve adequate reduction of the radial head. De Boek et al. [20] reported open reduction without annular ligament reconstruction and ulnar osteotomy in four patients with neglected Monteggia fracture dislocation. Their research showed excellent results. Nevertheless, patients who had healed or deformed ulna were excluded from their series [20]. On the other hand, Ladermann et al. [19] preferred ulnar osteotomy in all of their cases. They only recommend open radial head reduction when the reduction is not achieved spontaneously after the ulnar osteotomy [19].

The radiocapitellar joint is very sensitive to ulna length [19]. Therefore, ulnar osteotomy is the keystone treatment in achieving and maintaining reduction of the radial head in Monteggia fracture dislocation. Additionally, forearm bones work as an articular unit during supination and pronation; therefore, satisfied functional outcomes depend on achieving an optimum ulnar length. Ulnar fixation may be accomplished with pins, screws or plates [19]. We preferred simple intramedullary pin fixation; because, it needs minimal incision and avoids the problem of retained hardware (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timeline of the case report.

| 4 weeks before operation | Operation time | At 8th week of follow-up | At the 12th week of follow-up | At 16th week follow-up | Postoperative 1 year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall down from a swing | Admission to our hospital | PIN started to recover slowly. | Callus formation was viewed in X-ray. | All of functions of the PIN were returned. | Full range of elbow motion |

| Right elbow pain | Monteggia Bado type III and PIN palsy were diagnosed. | The intramedullary Kirchner was removed. | The radiocapitellar joint congruency was achieved in X-ray. | ||

| Restricted motion | Operated | Mayo elbow performance index was 100. | |||

| No hospital administration |

Several surgeons recommend immediate open anatomic reduction of both the ulna fracture and the radial head dislocation [6], [9], [11], [19]. Delpont et al. reported good long term outcomes of the open anatomic restoration even one year after the injury [9]. Nakamura et al. [6] performed the open reduction of the radial head combined with ulnar osteotomy and annular ligament reconstruction in 22 pediatric cases. Their retrospective evaluation were showed that if the open reduction was performed when the patient was less than 20 years of age or within 3 years after the injury, good long term clinical and radiographic outcomes would be expected [6]. In our case, we preferred a similar technique as soon as the injury was diagnosed, which resulted satisfactory functional and radiographic outcomes.

Necessity of the radiocapitellar fixation is an another matter of debate in the treatment of Monteggia lesions. Although some authors advocate radiocapitellar fixation with the temporary Kirchner wire, some authors warn about a possible pin migration and osteoarthritic changes due to radiocapitellar pinning [5], [9], [17]. Delpont et al. [9] suggested that if the radial head is unstable after the ulnar osteotomy, surgeons should consider revising ulna osteotomy in terms of radiocapitellar pinning [9]. To achieve stable radiocapitellar joint was possible after the ulnar osteotomy; therefore, we did not employed pinning.

To decide whether to repair or reconstruct the annular ligament remains controversial. Some authors prefer annular ligament reconstruction in every case, however some others stated that the annular ligament reconstruction did not affect the radiocapitellar stability [4], [9], [11]. Tan et al. [13] reported that annular ligament was intact and interposed within the radiohumeral joint in their 35 pediatric cases of Monteggia injury. They advocate the open reduction of the annular ligament in every case [4], [13]. In chronic Monteggia lesions, if the annular ligament repair cannot be accomplished, reconstruction should be performed to achieve radiocapitellar joint stability [5], [10].

The incidence of PIN palsy in Monteggia fracture-dislocation has great variety in the literature (3.1% to 31.4%) (14). PIN palsy is generally recover after the anatomical reduction of the radial head as happened in our case [4], [13], [15], [16]. Controversially, Li Hai et al. suggested that every case of type III Monteggia fracture dislocation with concomitant PIN palsy and an irreducible radial head should be viewed as an indication for immediate surgical exploration to exclude PIN entrapment [14].

4. Conclusion

Whether acute or chronic, Monteggia injuries remain challenging for orthopedic surgeons. In case of neglected injury, there is no consensus about the definitive treatment in the literature. We presented a case of neglected Bado type III Monteggia fracture dislocation who underwent open reduction of the radial head, transverse ulnar osteotomy, annular ligament repair without exploring PIN, and observed excellent functional and radiographic outcomes. Therefore, we recommend anatomic and stable restoration of radiocapitellar joint by correcting ulna deformity. Radiocapitellar fixation and PIN exploration may not be necessary in all cases.

Conflict of interest

The presence or absence of the conflict of interest (COI) should be declared for the individual authors like “Mehmet DEMİREL, Yavuz SAĞLAM, Onur TUNALI declare that they have no conflict of interest."

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Advocate Health Care Institutional Review Board does not require review for case reports.

Consent

Appropriate consent from the patient was obtained per institutional protocol and guidelines. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

(1) Mehmet Demirel, MD: drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for important intellectual clinical content; (2) Yavuz Sağlam, MD: equal contribution as lead author, drafting of the article, revision of the article for important intellectual clinical content; (3) Onur Tunalı, MD: revision of the clinical and intellectual content of the article.

Guarantor

Yavuz Sağlam, MD.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology.

References

- 1.Rehim S.A., Maynard M.A., Sebastin S.J., Chung K.C. Monteggia fracture dislocations: a historical review. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2014;39(July (7)):1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bado J.L. The Monteggia lesion. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1967;50:71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gleeson A.P., Beattie T.F. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. J. Accid. Emerg. Med. 1994;11(3):192–194. doi: 10.1136/emj.11.3.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ristic S., Strauch R.J., Rosenwasser M.P. The assessment and treatment of nerve dysfunction after trauma around the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;370:138–153. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datta T., Chatterjee N.D., Pal A.K., Das S.K. Evaluation of outcome of corrective ulnar osteotomy with bone grafting and annular ligament reconstruction in neglected Monteggia fracture dislocation in children. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.: JCDR. 2014;8(6):LC01. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9891.4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K., Hirachi K., Uchiyama S., Takahara M., Minami A., Imaeda T., Kato H. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2009;91(6):1394–1404. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneeberger A.G., Kösters M.C., Steens W. Comparison of the subjective elbow value and the Mayo elbow performance score. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George A.V., Lawton J.N. Management of complications of forearm fractures. Hand Clin. 2015;31(2):217–233. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delpont M., Jouve J.L., de Gauzy J.S., Louahem D., Vialle R., Bollini G., Cottalorda J. Proximal ulnar osteotomy in the treatment of neglected childhood Monteggia lesion. Orthop. Traumatol.: Surg. Res. 2014;100(7):803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg P., Baid P., Sinha S., Ranjan R., Bandyopadhyay U., Mitra S.R. Outcome of radial head preserving operations in missed Monteggia fracture in children. Indian J. Orthop. 2011;45(5):404. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.83946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guitton T.G., Ring D., Kloen P. Long-term evaluation of surgically treated anterior Monteggia fractures in skeletally mature patients. J. Hand Surg. 2009;34(9):1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drosos G.I., Oikonomou A. A rare Monteggia type-I equivalent fracture in a child. A case report and review of the literature. Inj. Extra. 2012;43(12):153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan J.W., Mu M.Z., Liao G.J., Li J.M. Pathology of the annular ligament in paediatric Monteggia fractures. Injury. 2008;39(4):451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hai L., Qi-xun C., Pin-quan S., Ting C., Zi-ming Z., Li Z. Posterior interosseous nerve entrapment after Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2013;16(3):131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce H.E., Harvey J.P., Wilson J.C. Monteggia fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1974;56(8):1563–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith F.M. Monteggia fractures; an analysis of 25 consecutive fresh injuries. Surg. Gynecol. Obstetrics. 1947;85(5):630–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David-West K.S., Wilson N.I., Sherlock D.A., Bennet G.C. Missed Monteggia injuries. Injury. 2005;36(10):1206–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiley J.J., Galey J.P. Monteggia injuries in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 1985;67(5):728–731. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B5.4055870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goyal T., Arora S.S., B19anerjee S., Kandwal P. Neglected Monteggia fracture dislocations in children: a systematic review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 2015;24(3):191–199. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Boeck H. Treatment of chronic isolated radial head dislocation in children. Clin. Orthop. 2000;380:215–219. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200011000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]