Abstract

Chronic heart failure (CHF) among Aboriginal/Indigenous Australians is endemic. There are also grave concerns for outcomes once acquired. This point is compounded by a lack of prospective and objective studies to plan care. To capture the essence of the presented topic it is essential to broadly understand Indigenous health. Key words such as ‘worsening’, ‘gaps’, ‘need to do more’, ‘poorly studied’, or ‘future studies should inform’ occur frequently in contrast to CHF research for almost all other groups. This narrative styled opinion piece attempts to discuss future directions for CHF care for Indigenous Australians. We provide a synopsis of the problem, highlight the treatment gaps, and define the impediments that present hurdles in optimising CHF care for Indigenous Australians.

Keywords: Aboriginal Australian, Chronic Heart Failure, Cultural Health Attributions, Culture and Healthcare, Health Beliefs, Indigenous Australian

INTRODUCTION

‘Politics is the art of the impossible and science is the art of the possible’

Unknown

Have we made inroads in improving chronic heart failure (CHF) outcomes for Indigenous Australians? We have certainly made inroads in delivery of services and therapeutics for most urban centres. In addition, the evidence seems to indicate that trial outcomes have been reproduced for the wider Australian population and worldwide [1-3]. Without definitive prospective data, anecdotal data suggests otherwise for Indigenous patients, anywhere in Australia [4-11]. Some may even suggest that we are going backwards [12]. Some have raised the notion of ‘cultural sensitivities’, the simplest way to highlight this point is to ask the question ‘would it be acceptable to conduct a RCT among Indigenous Australians and apply the findings to all Australians?’ Thus more attempts are needed to refocus the question on the community in front of us rather than implement solutions more relevant for others. Many still consider the medical issues of the first Australians as too hard. The politics continue to tell us to believe change is around the corner, while the science tells us we may be going backward. But the truth of the matter is that neither of these two arms meet regularly to continue the dialogue on how to improve care. It does however highlight that there are poles between scientific possibilities, political will and community sentiment on Indigenous affairs. It would be timely for all these factions to draw more on the commonalities to address the challenges.

CHF is a chronic condition without cure. The epidemiology which is well studied highlight that CHF: is a top three cause for admissions among older Australians; has a 5 year mortality approaching 50%; is associated with chronic co-morbidities in the majority of cases; impacts the demand for medical and allied health care in hospital and the communities. The direct healthcare costs from these wide-ranging needs account for 2% of many developed nations’ health budgets, the majority related to admissions. Thus there is a health strain even for mainstream HF care [11]. For Indigenous Australians, the difference in their socio-geo-political demographics leads to imbalance between services needs and disease epidemiology, far greater than can be planned for. In this we have to factor in cultural sensitivities, which have never been translated at a population level for Indigenous clients [13, 14].

Ensuring whether CHF guidelines are implemented broadly is an important start as demonstrated by the OPTIMIZE-HF study. It is also important we consider broader issues [10, 11]. As there are diverse treating health clusters, some consensus on the direction is required. Examples of this include broader considerations in developing and applying guideline evidence [15, 16]. Lenzen et al, argues that less than 10% of CHF patients are eligible for the randomised controlled trials (RCT) that inform guidelines [17]. There are issues for Indigenous patients at the very heart of the evidence tree. Thus we have to not only ask, ‘why does such a devastating health care gap still exist?’ but ‘does the conventional treatment strategies also contribute to the health care gaps?’ In short, are evidenced based CHF guidelines generalizable for our Indigenous clients and what really is the evidence base? In this review we aim to explore impediments and avenues to improve CHF care for Indigenous Australians.

Disparities in Heart Failure Outcomes

CHF from all perspectives is suspected to be worse among Australia’s Indigenous population compared to Australians of any other ethnic background. There has never been a significant retrospective analysis or prospective study to confirm this [18]. Woods et.al reviewed this area and concluded that despite the shortfalls of available published data, Indigenous Australians have an excess burden of CHF, where undiagnosed cases may also be more common [4] (Box 1). If we look at what has been achieved in CHF care, from a nationwide retrospective analysis, HF was coded as the underlying cause of death in 4667 and mentioned anywhere on the death certificate in 20,614 cases, in 1997; and 3661 and 18491 respectively in 2003 representing decreases of 21.6% and 10%. Age standardised mortality rates were 17.1 and 78.8 per 100,000 person-years for the lowest and highest ages, thus mortality increased sharply with age, but overall decreased in all age groups and both sexes by 38% and 39%, over the study period. Age standardized mortality was higher in men than women. This excess decreased with higher ages and was reversed in over 85 year olds. The contribution of HF to deaths attributed to ischemic heart and circulatory diseases remained stable between 1997 and 2003 ranging from 24.8/24.1% and 18.3/17.3% respectively [2]. This would support a decline of greater than 37% since 2003 and with perhaps greater gains presently, and community wide. Subsequent studies have continued to support this improving trend. Smaller regional databases also support this finding [19-25].

Box. (1).

The Evidence tree: Efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

|

ABBREVIATIONS: ARF/RHD = acute rheumatic fever/rheumatic heart disease; CAD = coronary artery disease; CI = confidence intervals; NA = not available; PHC – primary health care. Modified from ref 4.

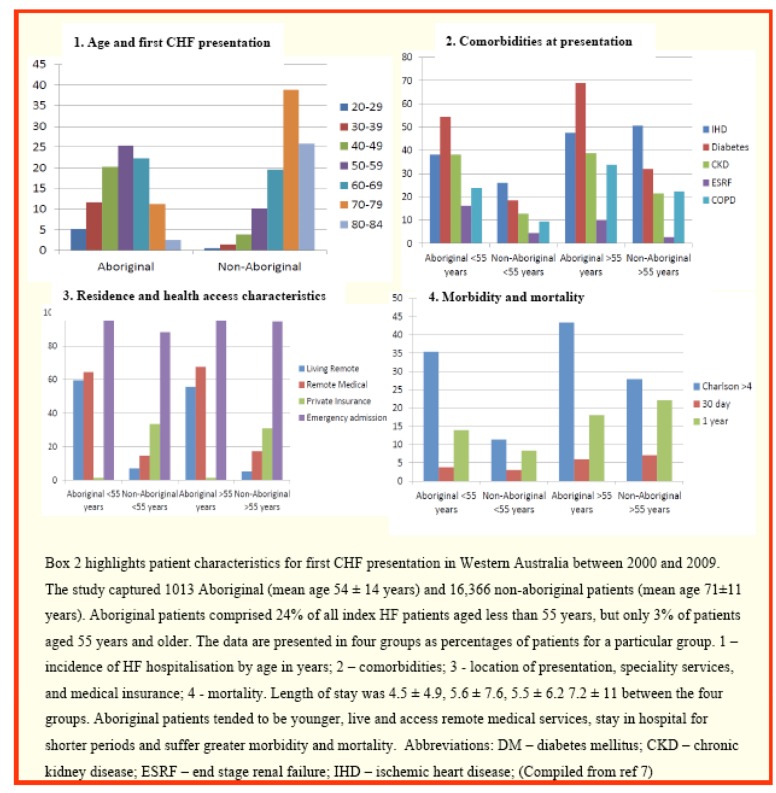

Specific to Indigenous Australians additional studies [6, 7, 26-28] not mentioned in the Woods paper, however suggest Indigenous patients are not doing as well (Box 2). Retrospective linked Western Australian hospital admissions data support improving CHF outcomes generally [20, 21, 23], but data for Indigenous clients show otherwise [6, 7, 29, 30]. Among 17 379 index HF patients, Teng et.al identified 5.8% of 1013 clients as Indigenous. Incidence HF rates were 11 and 23 times higher in young males and females dropping to 2 times in the oldest group. In general, these patients tended to be younger, female and more likely to reside remotely. Ischemic and rheumatic aetiologies were more common in younger age groups. All groups had higher proportions with comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive airways disease and a high Charlson comorbidity index, similarly noted by McGrady et al. 12 month mortality was 1.9 times higher in Indigenous patients below 59 years of age. Geographically, in the total cohort only 1.9% of Indigenous clients resided in a metropolitan address and 17.2% were from remote areas. The authors noted remoteness contributes to variable access to health care and is an independent predictor for poorer health outcomes [5, 6, 7, 31, 32]. Despite these significant gaps there is evidence to show that we are capable of making inroads, but this requires common sense and getting’s some basics right [33]. The bigger question is whether we can sustain such efforts for long periods, given the transitional nature of scientific funding and political sentiment. Regardless, to move forward we need to explore contrasting views on health and illness and understand the willingness from all sides to find common ground.

Box. (2).

Demography for first heart failure admission in Western Australia.

Does Traditional Indigenous Life-styles Represent an Impediment to Management of Chronic Heart Failure?

“Contemporary bioethics recognizes that medicine manifests social and cultural values and that the institutions of health care cannot be structurally disengaged from the sociopolitical processes that create such values.”

Jean-Francis Leotard 1988 [10]

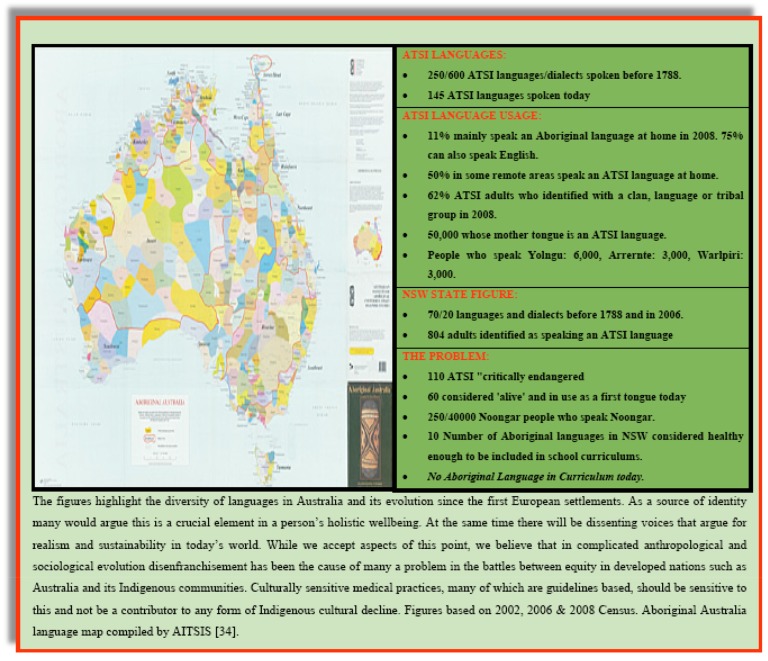

Is there a disconnect between the Western treatment paradigm for chronic ambulatory health care diseases such as CHF and the Indigenous way of life? We have deliberately labeled this section using the phrase ‘Way of Life’, as the 40,000-year-old Indigenous culture was the likely common starting place for our shared humanity. Paradigms evolved from here. Not enough is spoken of, to ensure we understand and cherish the richness of this nomadic society and the successes they have had, living in such a harsh environment in the driest continent on earth. Box 3 explores a small but important part of this, by looking purely at Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages (ATSI) [34]. There is undoubtedly a clash of cultures within and external. We could explore this from 3 points:

Box. (3).

Languages of Aboriginal Australia.

-

Cultural Values and Health:

Is the traditional Indigenous view of health and life-style an impediment to management of CHF?

Is the Western view of health and life-style impeding optimal CHF management for Indigenous Australians?

-

Common Ground between Cultures:

Is the traditional Indigenous life-style adaptable/compatible with current models, or are new approaches needed?

Is the Western view of ambulatory health care adaptable/compatible with delivering optimal CHF care for Indigenous clients?

Are there areas of overlap?

-

Unanticipated Cultural Changes:

Is the current delivery of the Western paradigm of Ambulatory Health Care changing the Traditional Indigenous way of life?

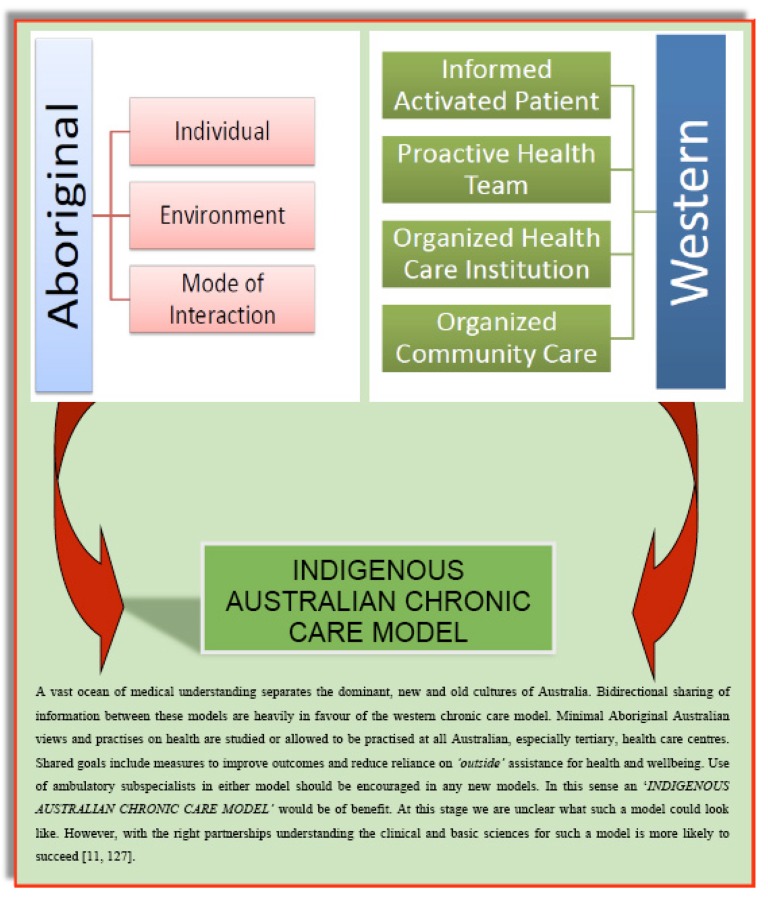

A decisive debate between stakeholders who deliver and receive healthcare in Indigenous Health is required to develop an agreed framework from both parties, which we can successfully implement. However, we do not feel this is achievable in the current climate, at least outside a research domain. A defining summary on traditional Indigenous views on health has been provided by Maher and is sufficiently authoritative to ensure it is essential reading for any medical context [35]. Similarly health system perspectives on Indigenous health have been summarised [14, 33-49]. What is lacking is direct information from the Indigenous clients themselves. The published work is diverse, but does not appear coherent [49]. There is a lack of sustained lockstep measures addressing one issue from multiple angles (Box 4). Exceptions include work from Brown et al, which provide strong foundations, with elements that are implementable [47], to continue a program of work [50-54].

Box. (4).

GULFS APART – Two models of disease within the new and old cultures of Australia.

Thus to answer the above question, can we deliver best practice using the Indigenous model, the Western model or a new model, is not possible. From the Western perspective, we know it is difficult to consider broader treatments to cater for the high burden of CHF with comorbidities, or similarly look to implement therapies that factor in reducing pill burden, pill size, agents with potential extra class effects and agents with potential for fewer side effects or adverse drug interactions [15, 16]. In essence the guidelines have not factored in this scenario. Furthermore if we are to acknowledge aspects of traditional medicines, enhancing extended family networks in care, understanding the nomadic and behavioural elements such as diet and even sleep wake cycles, we continue to show greater gaps, again raising questions of ‘culturally sensitivy’. From the Indigenous perspective we fail the most by not understanding chronological and hierarchical priorities in health care which affect uptake of chronic condition care. Collectively, principles that guide drug compliance could be universal highlighting the importance of simplified treatment regimes.

Thus we have a very complex situation, with potential for stalemate all round. Western and liberal values that shape the fabric of Australian societies on health and wellness, social communication, interpersonal relationships spill over into the healthcare system. Medical systems that share these values can negatively impact on those who are ‘foreign’ to such principles. Moving forward a new approach with bidirectional transfer of information with respect and understanding could be considered. We feel, at this point no one person or group is certain what this new paradigm could or should look like. We also feel that because of the close relationship between culture, socioeconomics and health and the potential for intergenerational impacts of chronic conditions management, a dedicated team with control over the process should pursue a quasi-experimental path for a sustained period. Success should not be the benchmark, but obtaining findings with a high sensitivity, specificity and validity should be the premise. Let us explore such viewpoints in more detail.

Box 3. Languages of Aboriginal Australia.

“The world is immediate, not external, and we are all its custodians, as well as its observers. A culture which holds the immediate world at bay by objectifying it as the Observed System, thereby leaving it to the blinkered forces of the market place, will also be blind to the effects of doing so until those effects become quantifiable as, for example, acid rain, holes in the ozone layer and global economic recession. All the social forces which have led to this planetary crisis could have been anticipated in principle, but this would have required a richer metaphysics. Aboriginal people are not against money, economics or private ownership, but they ask that there be recognition that ownership is a social act and therefore a spiritual act. As such, it produces effects in the immediate world which show up sooner or later in the 'external' world. What will eventually emerge in a natural, habituated way is the embryonic form of an intact, collective spiritual identity for all Australians, which will inform and support our daily lives, our aspirations and our creative genius”.

Mary Graham 1999 [43]

Behavioural Bases for Poor Indigenous Outcomes

As, Maher has detailed [35], the heterogeneity and generational transfer through spoken means, implies that the traditional Indigenous culture is more complex than what is documented. In addition, while personal experience is plentiful, actual publications are few. As such we will explore 5 areas in this section through a combination of a consensus of personal experiences and published evidence.

Box 4. GULFS APART – Two models of disease within the new and old cultures of Australia.

Compliance and Attitudes to Taking Pills

It is a difficult proposition for any client to consider a lifetime of medications. This proposition becomes more difficult when there are multiple agents, multiple dosing intervals, larger pill sizes, potential side effects, comorbid conditions, language barrier to communicate this, long intervals between specialist consultations and large distances to travel. Most of us who provide care to Indigenous clients will agree that there are few issues in the acute setting, perhaps consistent with similarities in both health paradigms. There remain concerns about longer-term compliance. We continue to feel that this area is under-resourced for Indigenous CHF care. In regards to chronic health care, additional confounders such as the supernatural and the environment could shape thinking and thus belief in the value of medications and henceforth compliance. However some of these illness categories have only developed in the last century; as such it is unclear if communities solely use older systems to explain this. Again most of us feel that the majority of indigenous patients do initially attempt to comply, but remain unclear how they may respond should therapies become more complicated, cause side-effects or are seen to be ineffective. Evidence from interventions in the Western paradigm proposes that this is a universal phenomenon, and remains a difficult issue to address [55], even for non-pharmaceutical treatments [56, 57].

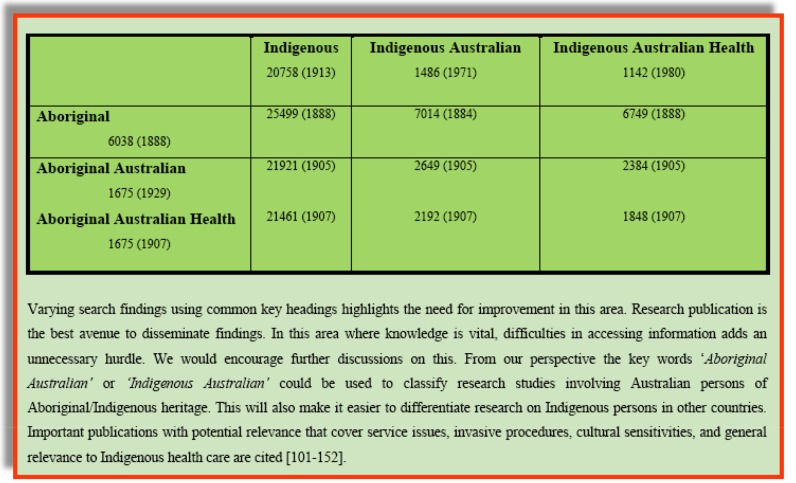

Box 5. Search differentials using common keywords.

Adverse Drug Reactions

There are no data on side-effect rates for Indigenous clients and it will remain difficult to obtain. Publications involving elderly clients, who are more likely to have associated comorbidities and polypharmacy, report that the risk of adverse reactions increases from 13% for two drugs to 82% when taking more than seven drugs to 100% when using more than 10 drugs [58]. Specifically, for beta-blockers, the COPERNICUS study with carvedilol reported drug-related adverse events in 3-5% (mainly bradycardia, hypotension and syncope) with similar findings from the SENIORS study in older CHF clients, with reported rates of 4-17% for these symptoms. Tolerability over the trial periods averaged 65-70%. With spironolactone, RALES reported severe hyperkalaemia in only 2%. In older cohorts, other authors reported severe hyperkalaemia in 11%, acute kidney injury in excess of 37% and discontinuation rates of 34% [59, 60]. Adverse reactions are likely high, under-reported, a cause for submaximal dosing and lower compliance among Aboriginal patients.

Consequences of Isolation

Isolation in the Indigenous context, predominately geographical and socio-cultural, poses problems with drug monitoring. The most important of these may simply be the inability to communicate a common side effect such as dizziness after ACE-I initiation or not being able to regulate fluid intake when the weather changes. Large distances and service gaps could thus lead to under prescription of therapy [16, 61, 62] and the inability to communicate due to language and understanding, inability to attend clinics due to circumstances within the extended family dynamic or cultural stigmas of embarrassing side-effects are important considerations.

Comorbidities that Alter Pharmacotherapy Prescription or Efficacy

Medical conditions that co-exist with CHF are common among Indigenous Australians. Risk factors for CHF are also at epidemic levels where, diabetes rates are 3-10 times, obesity rates twice and renal impairment 4-10 times those of non-Indigenous Australians [63-66]. In addition alcohol consumption is excessive and rheumatic heart disease rates are among the highest in the world [31]. Metabolic syndromes including impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia are more likely to be adversely affected by beta-blockers. Furthermore, ACE-I and spironolactone are under prescribed in patients with kidney disease [67].

Box 6. Theoretical constructs for clinician-scientist collaborative development of an indigenous-Australian chronic care model.

Different Basis for CHF

Potential antecedents to CHF among Indigenous Australians are also poorly studied. Key risk factors include coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, rheumatic heart diseases [31], and renal impairment [66]. Pharmacokinetic differences should also be considered. We have previously described differential cytochrome P450 metabolism for metoprolol as one example. Polymorphisms of adrenergic and RAAS receptors could affect therapeutic efficacy and side-effect profiles. Specifically differential responses to beta-blockers [68, 69] and RAAS blockade have been reported [16, 70, 71]. Hypertension, present in more than half of CHF patients, has a different pathophysiological basis in African Americans. In these patients diuretics, aldosterone blockade and vasodilators appear more efficacious. The A-HEFT study extended this evidence to the CHF population [72]. Rheumatic heart disease contributes to CHF in early life, with the burden of illness being particularly high in women of childbearing age. Diabetic and renal impairment contributes to CHF in unique ways that may require additional consideration for the use of reno-protective agents, different drugs within a class and more aggressive anti-thrombotic agents. Myocardial energetics [73] is another example of an important area to consider in the complex pathophysiological milieu that exists in HF patients with comorbidities.

Patient Reported Outcomes

Finally it also worth investing in understanding how patient reported outcomes are different for the Indigenous Community [153].

Potential Differential Treatment Strategies

Whether our current approach needs an overhaul or a tweak, the process to get there is the same. We are practising medicine in a climate where diseases are increasing in chronicity and complexity; all the while the evidence gathering process and guidelines have become more rigid. However we feel the process moving forward should be a simple, but is perhaps easier said than done. If we suggest that the guidelines should be more culturally sensitive, we first need to ask, what could such cultural sensitivities be? Answering this question takes us back to the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ of first do no harm, and secondly informed prescribing practices. This would imply understanding the impacts of a treatment and treatment plan on an individual’s quality of life and their way of life. Three important examples of this are pill burden, dosing frequency and chronology in decision making for procedures. Pushing for guidelines-based therapies may necessitate rapid decision-making and polypharmacy chronically. The different chronological views in the ‘Aboriginal Model of Causation’ may see a client accept an acute intervention but reject making a decision for surgery at a later date. Similarly hospital compliance is good but not out of hospital, which could range from missing parts of one’s treatment such as the night-time dose, to omitting larger pills..Storage of medicines may also be an issue. A new treatment strategy must partly incorporate traditional Indigenous values. Before we can define the treatment strategy we need to explore the measures that took us here. Let us explore this from three perspectives:

Research and the evidence gathering process

A literature review in PubMed and Medline database using the words ‘Aboriginal’ and/or ‘Australian Health’ and/or ‘Indigenous’ and/or ‘Health’ identified 1848 references dating back to 1907, with 236 references from 2013-2014. The majority of references were themed under pregnancy, child and adolescents, covering domains of alcohol and tobacco, cardio-renal-metabolic and inflammatory diseases with minimal studies presenting positive data. There were 35 references for CHF from 3 main health services in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, published within the same language and paradigm (Box 5). Specific focus through the CSANZ and National Heart Foundation, have addressed coronary heart disease, risk factors and rhematic heart diseases, at the national level [55, 74-82]. The majority of the themes are focused on how we are failing to deliver best practice and introducing cultural sensitivities at the interpersonal level. There has been more sustained and increasing research in the last few years, but little evidence of continuity of findings from a successfully implemented programme at the population level. Rheumatic Heart Disease may be one exception to this, where some health professionals feel that in-roads have been made. There still remain overall concerns and in cardiology much research occurs without significant clinical cardiology input [83-88]. In summary the research process is fractured, lacking involvement of clinicians and thus generates few findings that are implementable.

Box. (5).

Search differentials using common keywords.

Emotional and Intellectual Disconnect

The ongoing negative outlook presented and fears of doing nothing often lead to calls for an immediate response, which cluster in silos of individuals or small groups. Well planned, group based decision making by stakeholders including communities, service providers and researchers with a plan backed by regular audits are more difficult but is a more sensible approach. In this regard, who sits at the table and acceptance of wide and varied opinions is important. It is also important that planning takes us ahead of the curve and we factor in tomorrow’s problems in today’s solutions.

An Australian Approach for an Australian Problem

The majority of guidelines have been informed by large RCT’s from international evidence. The only way to muster evidence for clients outside the inclusion criteria of the major trials is widen enrolment or generate local evidence. This evidence has to have an implementation flavour with system-wide relevance, thus ensuring that scarce research funds are not seen to be targeting fringe issues. The techniques used have to be novel so that while questions remained focused, findings could have a broad appeal. A memorandum of understanding for a program of work with local and external partners could address many of the issues raised.

Developing Evidence for a New Treatment Strategy

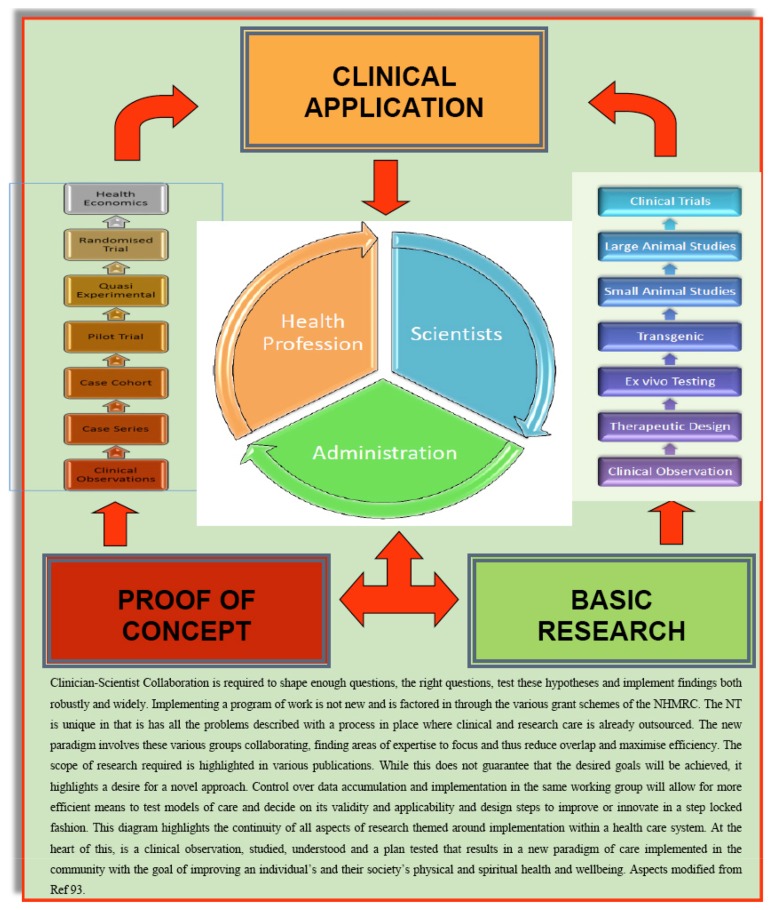

A new strategy has to have an Australian focus implementing locally generated evidence from an Indigenous perspective fused with the existing Western paradigm of chronic ambulatory care (Box 6). Three areas need to be addressed:

Box. (6).

Theoretical constructs for clinician-scientist collaborative development of an indigenous-Australian chronic care model.

-

Readiness for Reform (R4R):

Initially, a mapping exercise of both the communities and the currently available health services should be performed. This should be supplemented by gathering evidence if it is lacking or lobbying if there is already evidence. As an example, enrolment of Indigenous communities in large RCT’s has historically been poor. Clinical trialists need to develop strategies to ensure enrolment of indigenous patients in large RCT’s and secure industry funding for post marketing audit should new treatments be implemented in communities via the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. In addition, efforts to open communication lines into ongoing taboo areas such as transplantation or medical genetics are required.

-

Defining an appropriate care model and finding evidence for it:

-

Identifying key stakeholders from the community and medical systems:

Separation of primary health care (PHC) and tertiary health care is an area that needs to be looked at closely. Indeed, there is considerable overlap between PHC clinics and tertiary centres, such that they should be viewed as a continuum rather than separation. We need to increase our understanding of Indigenous medical practices and allow elements of it in tertiary centres rather than seeing clients discharged to seek such care.

Movement/Migration (Nomadic Patients): We should develop suitable models to account for nomadic traditional lifestyles. Biometrics, centralised storage and accessibility of information are perhaps some elements to address. In Australia where health care funding and delivery are shared between state and federal governments, we need to be open to more cooperative models.

Defining suitable research studies for the program: Broadening the questions may also broaden answers. Obtaining the right sample sizes guided by appropriate power calculations will increase both the internal and external validity of the findings. As this may not always be achievable, alternative strategies such as quasi-experimental design, with novel statistical approaches e.g. pseudo-randomisation techniques such as regression adjustment, propensity matching, inverse probability weighting and instrument variables to name a few could be explored [89]. Medical genetics could also be important [154].

Clinical (Bedside) Research: We have previously highlighted clinical audits, self-care, client-journey/experiences, staff skills, technologies and simplifying therapeutics as priorities [15, 16, 18, 90-92]. Finding ways to relinquish care to clients, extended social networks, increasing staff skills and expertise, utilising technology appropriately and simplifying the medical experience are important considerations.

Basic (Bench) Research: We have previously highlighted biomarkers, pharmaceuticals with extra class effects and genetics in the cardio-renal-metabolic axis as priorities [93]. It could be an avenue to fine-tune existing evidence to ensure greater external appeal or find new evidence to take to the bedside.

Phase 4 Studies - Health Economics and Translational Research: In addition to a drugs clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, we also need to consider total healthcare costs and how new models of care will be implemented in the metropolitan, regional, rural and remote settings [94-100, 155].

Traditional Therapies and Medical Anthropology: Efforts must be made to archive traditional knowledge and factor these into the medical curriculum. Its use within the western paradigm could then evolve.

-

CONCLUSION

With any therapy we should be sensitive of its impacts on our client’s way of life. Far too often treatments are provided with guidelines in mind first and clients preferences second. These issues can be accentuated when there are language and cultural differences. Not acknowledging cultural differences and not finding ways for services to accommodate marginalised groups are important contributors to the problems. However to define a program of work and succesfully implement them requires an understanding between key stakeholders such as the service providers, researchers and administrators. This document aims to describe part of that journey in improving CHF care for Indigenous Australians, with the lessons we learnt and the solutions we propose. Finally in any solution the treatment modality must be responsible and responsive to the cultural affiliations and socioeconomic realities of culturally distinct groups. To this extent it is incumbent on the Australian medical profession to invest in local studies that will tailor to the needs of this community, and similarly other countries for their Indigenous peoples.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATSI

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

- CHF

Chronic Heart Failure

DISCLOSURES

All co-authors have won independent and governmental research funding. Several members provide counsel to pharmaceuticals. None pose a conflict of interest for this review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Najafi F., Dobson A.J., Jamrozik K. Recent changes in heart failure hospitalizations in Australia. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2007;9:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Najafi F., Dobson A.J., Jamrozik K. Is mortality from heart failure increasing in Australia? An analysis of official data on mortality for 1997-2003. Bull. World Health Organ. 2006;84(9):722–728. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.031286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J., Dharmarajan K., Wang Y., Krumholz H.M. National Trends in Heart Failure Hospitalization Rates, 2001–2009. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(10):1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods J.A., Katzenellenbogen J.M., Davidson P.M., Thompson S.C. Heart failure among Indigenous Australians: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2012;12:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrady M., Krum H., Carrington M.J., et al. Heart failure, ventricular dysfunction and risk factor prevalence in Australian Aboriginal peoples: the Heart of the Heart Study. Heart. 2012;98(21):1562–1567. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng T.H., Katzenellenbogen J.M., Hung J., et al. Rural-urban differentials in 30-day and 1-year mortality following first-ever heart failure hospitalisation in Western Australia: a population-based study using data linkage. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004724. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teng T.H., Katzenellenbogen J.M., Thompson S.C., et al. Incidence of first heart failure hospitalisation and mortality in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal patients in Western Australia, 2000-2009. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;173(1):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jhund PS. Long-Term Trends in First Hospitalization for Heart Failure and Subsequent Survival Between 1986 and 2003: A Population Study of 5.1 Million People. Circulation. 2009;119:515–523. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons K.J., Ezekowitz J.A., Liu W., McAlister F.A., Kaul P. Mortality outcomes among status Aboriginals and whites with heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2014;30(6):619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moe G.W., Tu J. Heart failure in the ethnic minorities. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2010;25(2):124–130. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328335fea4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyngkaran P., Harris M., Ilton M., et al. Implementing guideline based heart failure care in the Northern Territory: Challenges and Solutions. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(5):391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeremy R.W., Brown A. Measuring the gap—It may well be worse than we thought. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19:695–696. doi: 10.1016/S1443-9506(10)01530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aspin C., Brown N., Jowsey T., Yen L., Leeder S. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12:143. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garvey G., Towney P., McPhee J.R., Little M., Kerridge I.H. Teaching and learning ethics: Is there an Aboriginal bioethic? J. Med. Ethics. 2004;30:570–575. doi: 10.1136/jme.2002.001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyngkaran P., Thomas M., Sander P., et al. Do we need a Wider Therapeutic Paradigm for Heart Failure with Comorbidities? - A Remote Australian Perspective. Health Care Curr Rev. 2013;1:106. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyngkaran P, Majoni W, Cass A, et al. Northern Territory Perspectives on Heart Failure With Comorbidities - Understanding Trial Validity and Exploring Collaborative Opportunities to Broaden the Evidence Base. Heart Lung Circ. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.12.007. pii: S1443-9506(14)00821- X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenzen MJ, Boersma E. Under-utilization of evidence-based drug treatment in patients with heart failure is only partially explained by dissimilarity to patients enrolled in landmark trials: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2005;26:2706–2713. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyngkaran P., Tinsley J., Smith D., et al. Northern Territory Heart Failure Initiative – Clinical Audit (NTHFI – CA)- A Prospective Database on the Quality of Care and Outcomes for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Admission in the Northern Territory - Study Design and Rationale. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004137. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson J., McElduff P., Pearson S.A., Henry D.A., Inder K.J., Attia J.R. The health services burden of heart failure: an analysis using linked population health data-sets. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013;13:179. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng T.H., Hung J., Finn J. The effect of evidence-based medication use on long-term survival in patients hospitalised for heart failure in Western Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2010;192(6):306–310. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng T.H., Finn J., Hobbs M., Hung J. Heart failure. incidence, case fatality, and hospitalization rates in Western Australia between 1990 and 2005. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(2):236–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.879239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caughey G.E., Roughead E.E., Shakib S., Vitry A.I., Gilbert A.L. Co-morbidity and potential treatment conflicts in elderly heart failure patients: a retrospective, cross-sectional study of administrative claims data. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(7):575–581. doi: 10.2165/11591090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng T.H., Hung J., Knuiman M., et al. Trends in long-term cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in men and women with heart failure of ischemic versus non-ischemic aetiology in Western Australia between 1990 and 2005. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012;158(3):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranasinghe I., Naoum C., Aliprandi-Costa B., et al. Australia–New Zealand GRACE Management and outcomes following an acute coronary event in patients with chronic heart failure 1999–2007. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012;14(5):464–472. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean A.S., Eslick G.D., Coats A.J. The epidemiology of heart failure in Australia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007;118:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown A., Carrington M.J., McGrady M., et al. Cardiometabolic risk and disease in Indigenous Australians: the heart of the heart study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;171(3):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Artuso S., Cargo M., Brown A., Daniel M. Factors influencing health care utilisation among Aboriginal cardiac patients in central Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013;13:83. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peiris D., Brown A., Howard M., et al. Building better systems of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: findings from the Kanyini health systems assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12:369. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bureau of Health Information (NSW) Chronic Disease Care: Another piece of the picture. 2(2). Sydney: Bureau of Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katzenellenbogen J.M., Sanfilippo F.M., Hobbs M.S., et al. Aboriginal to non-Aboriginal differentials in 2-year outcomes following non-fatal first-ever acute MI persist after adjustment for comorbidity. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2012;19(5):983–990. doi: 10.1177/1741826711417925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrady M., Krum H., Carrington M.J., et al. Heart failure, ventricular dysfunction and risk factor prevalence in Australian Aboriginal peoples: the Heart of the Heart Study. Heart. 2012;98(21):1562–1567. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng T.H., Hung J., Katzenellbogen J.M., Bessarab D.C., Thompson S.C. Better prevention and management of heart failure in Aboriginal Australians. MJA. 2015;202(3):116–118. doi: 10.5694/mja14.01393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowley K.G., O’Dea K., Anderson I., et al. Lower than expected morbidity and mortality for an Australian Aboriginal population: 10-year follow-up in a decentralised community. MJA. 2008;188:283–287. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.http://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/language/

- 35.Maher P. A review of ‘traditional’ aboriginal health beliefs. Aust. J. Rural Health. 1999;7(4):229–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.1999.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McBain-Rigg K.E., Veitch C. Cultural barriers to health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Mount Isa. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2011;19:70–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durey A., Thompson S.C. Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: time to change focus. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12:151. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly J., Dwyer J., Willis E., Pekarsky B. Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country Aboriginal patient journeys. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2014;22(3):109–113. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherwood J., Edwards T. Decolonisation: A critical step for improving Aboriginal health. Contemp. Nurse. 2006;22(2):178–190. doi: 10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherwood J. Colonisation – Its bad for your health: The context of Aboriginal health. Contemp. Nurse. 2013;46(1):28–40. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saethre E.J. Conflicting Traditions, concurrent treatment: Medical Pluralism in remote Aboriginal Australia. Oceania. 2007;77:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaughn L.M., Jacquez F., Baker R.C. Cultural Health Attributions, Beliefs, and Practices: Effects on Healthcare and Medical Education. Open Med Education J. 2009;2:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham M. Some Thoughts about the Philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews. 1999.

- 44.Wedel J. Bridging the Gap between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua. Anthropol. Noteb. 2009;15(1):49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rix E.F., Barclay L., Stirling J., Tong A., Wilson S. The perspectives of Aboriginal patients and their health care providers on improving the quality of hemodialysis services: A qualitative study. Hemodial. Int. 2015;19(1):80–89. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reilly R., Rowley K., Luke J., et al. Economic rationalisation of health behaviours: the dangers of attempting policy discussions in a vacuum. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;114:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown A.D., Mentha R., Rowley K.G., Skinner T., Davy C., O'Dea K. Depression in Aboriginal men in central Australia: adaptation of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeremy R.W., Kritharides L., Brown A. Improving outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery: lessons from indigenous Australians. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22(8):597–598. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Azzopardi P.S., Kennedy E.C., Patton G.C., Power R., Roseby R.D., Sawyer S.M. The quality of health research for young Indigenous Australians: systematic review. Med. J. Aust. 2013;199(1):57–63. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jamieson L.M., Paradies Y.C., Eades S., et al. Ten principles relevant to health research among Indigenous Australian populations. Med. J. Aust. 2012;197(1):16–18. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown A., O'Shea R.L., Mott K., McBride K.F., Lawson T., Jennings G.L. Essential Service Standards for Equitable National Cardiovascular Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ESSENCE) Steering Committee. Essential service standards for equitable national cardiovascular care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(2):126–141. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown A., O'Shea R.L., Mott K., McBride K.F., Lawson T., Jennings G.L. Essential Service Standards for Equitable National Cardiovascular Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ESSENCE) Steering Committee. A strategy for translating evidence into policy and practice to close the gap - developing essential service standards for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cardiovascular care. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards L., Connors C., Whitbread C., Brown A., Oats J., Maple-Brown L. NT Diabetes in Pregnancy Partnership. Improving health service delivery for women with diabetes in pregnancy in remote Australia: survey of care in the Northern Territory Diabetes in Pregnancy Partnership. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014;54(6):534–540. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ilton M.K., Walsh W.F., Brown A.D., Tideman P.A., Zeitz C.J., Wilson J. A framework for overcoming disparities in management of acute coronary syndromes in the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. A consensus statement from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2014;200(11):639–643. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molloy G.J., O’Carroll R.E., Witham M.D., McMurdo M.E. Interventions to Enhance Adherence to Medications in Patients With Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:126–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nieuwenhuis M.M., Jaarsma T., van Veldhuisen D.J., Postmus D., van der Wal M.H. Long-term compliance with nonpharmacologic treatment of patients with heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110(3):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larkin C., Murray R. Assisting Aboriginal patients with medication management. Aust. Prescr. 2005;28:123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mastromarino V., Casenghi M., Testa M., et al. Polypharmacy in Heart Failure Patients. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2014;11:212–219. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erdmann E. Safety and tolerability of beta-blockers: prejudices and reality. Indian Heart J. 2010;62:132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sztramko R., Chau V. Adverse Drug Events and Associated Factors in Heart Failure Therapy Among the Very Elderly. Can. Geriatr. J. 2011;14(4):79–92. doi: 10.5770/cgj.v14i4.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clark R.A., Driscoll A., Nottage J., et al. Inequitable provision of optimal services for patients with chronic heart failure: a national geo-mapping study. Med. J. Aust. 2007;186(4):169–173. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kelly J., Dwyer J., Willis E., Pekarsky B. Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country Aboriginal patient journeys. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2014;22:109–113. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Cardiovascular Disease And Its Associated Risk Factors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2004-5. Cardiovascular Disease no 29. Cat No. CVD.41. Canberra: AIHW; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Adult Mortality between Aoriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Other Australians. Cat. No. IHW 48. Canberra: AIHW; 2010. Contribution of Chronic Disease To The Gap. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Cardiovascular Disease Series Cat no: CVD53. Canberra: AIHW; 2011. Cardiovascular Disease: Australian Facts 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Majoni S.W., Abeyaratne A. Renal transplantation in indigenous Australians of the Northern Territory: closing the gap. Intern. Med. J. 2013;43(10):1059–1066. doi: 10.1111/imj.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iyngkaran P., Thomas M., Majoni W., Anavekar N., Ronco C. Comorbid Heart Failure and Renal Impairment – epidemiology and Management. Cardiorenal Med. 2012;2(4):281–297. doi: 10.1159/000342487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Domanski M.J., Krause-Steinrauf H., Massie B.M., et al. BEST Investigators A comparative analysis of the results from 4 trials of beta-blocker therapy for heart failure: BEST, CIBIS-II, MERIT-HF, and COPERNICUS. J. Card. Fail. 2003;9(5):354–363. doi: 10.1054/s1071-9164(03)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mason P.R., Kalinowski L., Jacob R.F., Jacoby A.M., Malinski T. Nebivolol reduces nitric stress and restores nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelium of Black Americans. Circulation. 2005;112(24):3795–3801. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.556233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Havranek E.P. From Black and White to shades of Gray: Race and Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51:1872–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferdinand K.C., Ferdinand D.P. Race-based Therapy for Hypertension: Possible Benefits and Potential Pitfalls. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2008;10(6):1357–1366. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.10.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferdinand K.C., Elkayam U., Mancini D., et al. Use of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in African-Americans with heart failure 9 years after the African-American Heart Failure Trial. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014;114(1):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sverdlov AL, Elezaby A, Behring JB, et al. High fat, high sucrose diet causes cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction due in part to oxidative post-translational modification of mitochondrial complex II. Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.018. pii: S0022-2828(14)00244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nelson M.R., Doust J.A. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: new guidelines, technologies and therapies. Med. J. Aust. 2013;198(11):606–610. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rémond M.G., Wheaton G.R., Walsh W.F., Prior D.L., Maguire G.P. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease--priorities in prevention, diagnosis and management. A report of the CSANZ Indigenous Cardiovascular Health Conference, Alice Springs 2011. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown A., Brieger D., Tonkin A., et al. Coronary disease in indigenous populations: summary from the CSANZ indigenous Cardiovascular Health Conference. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kritharides L., Brown A., Brieger D., et al. Overview and determinants of cardiovascular disease in indigenous populations. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeremy R., Tonkin A., White H., et al. Improving cardiovascular care for indigenous populations. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brown A., Tonkin A., White H., et al. The Cardiac Society Inaugural Cardiovascular Health Conference: conference findings and ways forward. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kritharides L., Brown A., Brieger D., et al. CSANZ IHC Writing Group Recommendations arising from the inaugural CSANZ Conference on Indigenous Cardiovascular Health. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown A., Kritharides L. Overview: the 2nd Indigenous Cardiovascular Health Conference of the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):615–617. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crengle S., Smylie J., Kelaher M., et al. Cardiovascular disease medication health literacy among Indigenous peoples: design and protocol of an intervention trial in Indigenous primary care services. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):714. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maguire G.P., Carapetis J.R., Walsh W.F., Brown A.D. The future of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2012;197(3):133–134. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gray C., Thomson N. Review of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease among Indigenous Australians. Retrieved [access date] fromhttp://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/chronicconditions/ cvd/reviews/our-review-rhd . 2013.

- 85.Lawrence J.G., Carapetis J.R., Griffiths K., Edwards K., Condon J.R. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: incidence and progression in the Northern Territory of Australia, 1997 to 2010. Circulation. 2013;128(5):492–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.White H., Walsh W., Brown A., et al. Rheumatic heart disease in indigenous populations. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5-6):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Judd J., Keleher H. Building health promotion capacity in a primary health care workforce in the Northern Territory: some lessons from practice. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2013;24(3):163–169. doi: 10.1071/HE13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dyke T., Anderson W.P. A history of health and medical research in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2014;201(1):S33–S36. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Iyngkaran P., Liew D., Thomas M., et al. Phase 4 Trials in Heart Failure –What is done and what is needed? Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2015 doi: 10.2174/1573403X12666160606121458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Iyngkaran P., Toukshati S., Biddagardi N., Atherton J., Hare D. Technology Assisted Heart Failure Care. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2015;12(2):173–186. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iyngkaran P., Brown A., Cass A., Battersby M., Nadarajan K., Ilton M. Why it Remains Difficult for Remote Cardiologists to Obtain the Locus of Control for Ambulatory Health Care Conditions Such as Congestive Heart Failure? J. Gen. Pract. (Los Angel.) 2014;2:146. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Iyngkaran P., Vongayi M., Ilton M., et al. AUSI-CDS - Prospective observational cohort study to determine if an established chronic disease health care plan can be used to deliver better care and outcomes among Remote Indigenous Australians - Proof of Concept: Methods and Rationale. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22(11):930–939. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iyngkaran P., Thomas M.C. Bedside to Bench Translational Research for Heart Failure – Creating an agenda for Urban and Remote Australia. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2015;9(Suppl. 1):121–132. doi: 10.4137/CMC.S18737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCalman J., Tsey K., Bainbridge R., et al. The characteristics, implementation and effects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health promotion tools: a systematic literature search. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):712. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Judd J., Keleher H. Building health promotion capacity in a primary health care workforce in the Northern Territory: some lessons from practice. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2013;24(3):163–169. doi: 10.1071/HE13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stewart S. Nurse-led care of heart failure: will it work in remote settings? Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):644–647. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ward N.J., Jowsey T., Haora P.J., Aspin C., Yen L.E. With good intentions: complexity in unsolicited informal support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:686. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jowsey T., Yen L., Wells R., Leeder S. National Health and Hospital Reform Commission final report and patient-centred suggestions for reform. Aust. J. Prim. Health. 2011;17(2):162–168. doi: 10.1071/PY10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jeon Y.H., Essue B., Jan S., Wells R., Whitworth J.A. Economic hardship associated with managing chronic illness: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009;9:182. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schnell-Hoehn K.N., Naimark B.J., Tate R.B. Determinants of self-care behaviours in community-dwelling patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2009;24(1):40–47. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317470.58048.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Davidson P.M., Macdonald P., Moser D.K., et al. Cultural diversity in heart failure management: findings from the DISCOVER study (Part 2). Contemp. Nurse. 2007;25(1-2):50–61. doi: 10.5172/conu.2007.25.1-2.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Clark R.A., McLennan S., Eckert K., Dawson A., Wilkinson D., Stewart S. Chronic heart failure beyond city limits. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5(4):443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Coory M.D., Walsh W.F. Rates of percutaneous coronary interventions and bypass surgery after acute myocardial infarction in Indigenous patients. Med. J. Aust. 2005;182(10):507–512. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Prabhu A., Tully P.J., Bennetts J.S., Tuble S.C., Baker R.A. The morbidity and mortality outcomes of indigenous Australian peoples after isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery: the influence of geographic remoteness. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22(8):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee D.S., Stukel T.A., Austin P.C., et al. Improved outcomes with early collaborative care of ambulatory heart failure patients discharged from the emergency department. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1806–1814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.940262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Waldram J.B. Transformative and Restorative Processes: Revisiting the Question of Efficacy of Indigenous Healing. Med. Anthropol. 2013;32(3):191–207. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2012.714822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bharadwaj L. A framework for building research partnerships with first nations communities. Environ. Health Insights. 2014;8:15–25. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S10869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lawrance M., Sayers S.M., Singh G.R. Challenges and strategies for cohort retention and data collection in an indigenous population: Australian Aboriginal Birth Cohort. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014;14:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oliver S.J. The role of traditional medicine practice in primary health care within Aboriginal Australia: a review of the literature. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Senior K., Chenhall R. Health beliefs and behavior: the practicalities of “looking after yourself” in an Australian aboriginal community. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2013;27(2):155–174. doi: 10.1111/maq.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kant S., Vertinsky I., Zheng B., Smith P.M. Social, cultural, and land use determinants of the health and well-being of Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a path analysis. J. Public Health Policy. 2013;34(3):462–476. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kingsley J., Townsend M., Henderson-Wilson C., Bolam B. Developing an exploratory framework linking Australian Aboriginal peoples' connection to country and concepts of wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10(2):678–698. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10020678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bruner B., Chad K. Physical activity attitudes, beliefs, and practices among women in a Woodland Cree community. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2013;10(8):1119–1127. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Uprety Y., Asselin H., Dhakal A., Julien N. Traditional use of medicinal plants in the boreal forest of Canada: review and perspectives. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rigby C.W., Rosen A., Berry H.L., Hart C.R. If the land's sick, we're sick:* the impact of prolonged drought on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2011;19(5):249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Walji R., Weeks L., Cooley K., Seely D. Naturopathic medicine and aboriginal health: an exploratory study at Anishnawbe Health Toronto. Can. J. Public Health. 2010;101(6):475–480. doi: 10.1007/BF03403967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wilson K., Rosenberg M.W., Abonyi S. Aboriginal peoples, health and healing approaches: the effects of age and place on health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;72(3):355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ratsch A., Steadman K.J., Bogossian F. The pituri story: a review of the historical literature surrounding traditional Australian Aboriginal use of nicotine in Central Australia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010;12(6):26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Clarke V., Holtslander L.F. Finding a balanced approach: incorporating medicine wheel teachings in the care of Aboriginal people at the end of life. J. Palliat. Care. 2010;26(1):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Green B.L. Culture is treatment: considering pedagogy in the care of Aboriginal people. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2010;48(7):27–34. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100504-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shahid S., Bleam R., Bessarab D., Thompson S.C. “If you don't believe it, it won't help you”: use of bush medicine in treating cancer among Aboriginal people in Western Australia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jack S.M., Brooks S., Furgal C.M., Dobbins M. Knowledge transfer and exchange processes for environmental health issues in Canadian Aboriginal communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010;7(2):651–674. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Richmond C.A. The social determinants of Inuit health: a focus on social support in the Canadian Arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(5):471–487. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i5.17383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.King M. An overall approach to health care for indigenous peoples. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2009;56(6):1239–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dussart F. Diet, diabetes and relatedness in a central Australian Aboriginal settlement: some qualitative recommendations to facilitate the creation of culturally sensitive health promotion initiatives. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2009;20(3):202–207. doi: 10.1071/he09202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shahid S., Finn L., Bessarab D., Thompson S.C. Understanding, beliefs and perspectives of Aboriginal people in Western Australia about cancer and its impact on access to cancer services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009;31(9):132. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=CCM_Tools&s =237 .

- 128.McBain-Rigg K.E., Veitch C. Cultural barriers to health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Mount Isa. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2011;19:70–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mirzaei M, Yen L, Leeder SR. Epidemiology of chronic heart failure.The Serious and Continuing Illness Policy and Practice Study (SCIPPS), The Menzies Centre for Health Policy. 2007 URL: (access date: 14.08.2014). [Google Scholar]

- 130.AIHW. Heart, stroke and vascular diseases: Australian facts 2004. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2004. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/cvd/hsvd04/hsvd04.pdf . 2014. (accessed14.08.2014).

- 131.Hung J., Teng T.H., Finn J., et al. Trends From 1996 to 2007 in Incidence and Mortality Outcomes of Heart Failure After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Population-Based Study of 20 812 Patients With First Acute Myocardial Infarction in Western Australia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000172. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Clark R.A., McLennan S., Dawson A., Wilkinson D., Stewart S. Uncovering a hidden epidemic: a study of the current burden of heart failure in Australia. Heart Lung Circ. 2004;13:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Coory M.D., Walsh W.F. Rates of percutaneous coronary interventions and bypass surgery after acute myocardial infarction in Indigenous patients. Med. J. Aust. 2005;182(10):507–512. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Greaney D. Prevalence of Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Far North Queensland. Aborig. Isl. Health Work. J. 2010;34(5):36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Einsiedel L., Fernandes L., Spelman T., Steinfort D., Gotuzzo E. Bronchiectasis is associated with human T-lymphotropic virus 1 infection in an Indigenous Australian population. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54(1):43–50. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Carapetis J.R., Powers J.R., Currie B.J., et al. Outcomes Of Cardiac Valve Replacement For Rheumatic Heart Disease In Aboriginal Australians. Asia Pac. Heart J. 1999;8(3):138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Brown A. Acute Coronary Syndromes in Indigenous Australians: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes Across the Continuum of Care. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19(5–6):325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bolton A., Puranik R. Pilot project: Face to face cardiac clinic at the aboriginal medical service Redfern. Heart Lung Circ. 2011;20:S8–S9. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Thomas D.P., Heller R.F., Hunt J.M. Clinical consultations in an Aboriginal community-controlled health service: a comparison with general practice. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 1998;22(1):86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Clark R.A., Driscoll A., Nottage J., et al. Inequitable provision of optimal services for patients with chronic heart failure: a national geo-mapping study. Med. J. Aust. 2007;186(4):169–173. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.AIHW . Penm E. Cardiovascular disease and its associated risk factors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2004–05. Cardiovascular disease series no. 29. Cat. no. CVD 41. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 142.AIHW . Field B. Heart failure. . .what of the future? Bulletin no. 6. AIHW Cat. No.AUS 34. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, 2008 report: Detailed analyses. Cat.no. IHW 22. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2010: detailed analyses. Cat. no.IHW 53. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Nichol B, Lonergan J, Rhodes M. DHAC. Hospital case mix data and the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Department of Health and Aged Care Occasional Papers: New Series No. 3. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 146.Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision . Report on Government Services 2011, Indigenous Compendium. Canberra: Productivity Commission; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Expenditure on health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2008–09: an analysis by remoteness and disease. Health and welfare expenditure series no. 45. Cat. no.HWE 54. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Bureau of Health Information (NSW) Chronic Disease Care: A piece of the picture. 2(1). Sydney: Bureau of Health Information; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bureau of Health Information (NSW) Chronic Disease Care: Another piece of the picture. 2(2). Sydney: Bureau of Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Clark R.A., Driscoll A. Access and quality of heart failure management programs in Australia. Aust. Crit. Care. 2009;22(3):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vitry A.I., Phillips S.M., Semple S.J. Quality and availability of consumer information on heart failure in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008;8:255. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Close G.R., Newton P.J., Fung S.C., et al. Socioeconomic status and heart failure in Sydney. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(4):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Thompson L.E., Bekelman D.B., Allen L.A., Peterson P.N. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Heart Failure: Existing Measures and Future Uses. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2015;12(3):236–246. doi: 10.1007/s11897-015-0253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Iyngkaran P., Thomas M.C., Johnson R., et al. Contextualising genetics for regional congestive heart failure care. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2016;12(3):231–242. doi: 10.2174/1573403X12666160606123103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Iyngkaran P., Liew D., Macdonald P., et al. Phase 4 research in heart failure – where are we and what should be done? Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2016;12(3):216–230. doi: 10.2174/1573403X12666160606121458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]