Abstract

Objective

To describe the trends in mortality and the spectrum of disease in HIV-infected and -uninfected inpatients in a population in Yaoundé.

Design

A retrospective study.

Setting

Internal Medicine Unit, University Hospital Centre, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

Participants

All deaths registered between January 2000 and May 2007 in the unit.

Main outcomes measures

Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical features and results of all investigations done, cause of death.

Results

During the study period, 362 deaths were registered, consisting of 281 (77.6%) in HIV-infected patients, 54.4% of which were women. HIV-infected patients were younger (mean age: 40.2 (SD: 11.6) vs. 55.5 (SD: 18.3) years, p < 0.001) and economically active (60.3% vs. 24.4%, p < 0.001). Most HIV-infected patients (77.6%) were classified as WHO stage IV, with the rest being WHO stage III. Most HIV-infected patients (87.8%) had evidence of profound immunosuppression (CD4 < 200 cells/mm3). The mortality trend appeared to be declining with appropriate interventions. The most frequent causes of death in HIV-infected patients were pleural/pulmonary tuberculosis (34.2%), undefined meningoencephalitis (20.3%), other pneumonias (18.2%), toxoplasmosis (16.4%), cryptococcal meningitis (14.2%) and Kaposi sarcoma (15.7%). HIV-uninfected patients died mostly as a result of chronic diseases including liver diseases (17.3%), kidney failure (13.6%), congestive heart failure (11.1%) and stroke (9.9%).

Conclusion

There was a declining mortality due to HIV with appropriate interventions such as subsidised tests for HIV-infected patients, increased availability of HAART and other medications for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections. The spectrum of HIV disease was wide and preventable.

Keywords: HIV, mortality, morbidity, Cameroon, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

The human immune deficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic has caused far-reaching effects in low-income countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa. In 2012, 68% of all people living with HIV resided in sub-Saharan Africa, a region with only 12% of the global population.1 The same year, sub-Saharan Africa also accounted for 70% of new HIV infections and 67% of AIDS-related deaths.1 Situated in central Africa, Cameroon has the largest HIV/AIDS epidemic in this sub-region with an estimated HIV prevalence of 4.3%, 610,000 people living with HIV, 48,000 adults newly infected and 37,000 AIDS-related deaths reported in 2012.1

AIDS is the most common infection and cause of death among adults hospitalised in medical wards in several sub-Saharan African countries.2–9 The advent and widespread use of HAART and other preventive and therapeutic interventions have significantly improved the prognosis and quality of life of people living with HIV, with a drastic reduction in mortality and morbidity related to HIV and its complications.1,10,11 Although these positive results have been achieved, it remains necessary to continuously monitor the incidence and the disease spectrum of AIDS in order to improve interventions to control it.

More than 10 years after the introduction of HAART in Cameroon, there is still a scarcity of data on the morbidity and mortality patterns in the HIV-infected population in the country. This study aimed to assess mortality and causes of death among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients admitted in the Internal Medicine Unit of the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre in the HAART era. Data will contribute to appropriate preventive policies and care of HIV-related morbidities and causes of death, a good case scenario for other similar sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective hospital register-based cohort study in the Internal Medicine Unit of a major tertiary hospital, the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre which serves as a referral centre for AIDS and other internal medicine pathologies for the capital city of Cameroon (Yaoundé) and surrounding areas. The Yaoundé University Hospital Centre is one of the centres providing the best medical services in Cameroon. Patients from all social classes attend this hospital, mainly patients from surrounding urban areas but also those from semi-urban and rural areas requiring specialised care. All deaths registered from January 2000 to May 2007 were considered for inclusion. We excluded deaths of unknown or unstated cause.

Detection and management of HIV infection

Patients were screened for HIV after informed consent. As recommended by the national guidelines, HIV antibodies were detected by two rapid tests which detect both HIV-1/2 infections: an indirect solid-phase enzyme immunoassay, the Immunocomb, HIV 1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics, Courbevoie, France) and an immunochromatographic assay, the Determine HIV-1/2 (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA). All samples positive for both techniques were considered true positives, and those negative for both methods were considered true negatives. For discordant tests, a confirmatory Western blot test (New Lav; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Chaska, Minnesota, USA) was conducted. A subject was defined as HIV-infected if he had a positive result based on the aforementioned technique. AIDS was defined based on stages III and IV categories of the World Health Organization classification.

All HIV-infected patients were started on prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole, while those with a CD4 lymphocyte count <200 cells/mm3 were started on triple antiretroviral therapy free of charge. Initial antiretroviral regimens consisted of two nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors + one non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (the combinations Lamivudine-Zidovudine-Efavirenz or Lamivudine-Stavudine-Efavirenz) for instance.

Data collection

The cause of death was defined as the main conditions that initiated the sequence of events resulting in death. Cause of death was determined by the infectious disease or internal medicine specialist who had taken care of the patient. No postmortem findings were available. Data collected included sociodemographic characteristics, HIV status, HIV treatment, clinical findings, and findings from oriented haematological, biochemical, microbiological, histopathological, morphological exams and causes of death.

Data analysis

Data were coded, entered and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). In order to study the impact of HIV infection on the patterns of morbidity and mortality in the hospital, we divided our study population into two groups and compared them: HIV-infected patients and HIV-uninfected patients. We described continuous variables using means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges and categorical variables using their frequencies and percentages. We used the Chi-squared test for comparison of categorical variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests for continuous variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre.

Results

Background characteristics of study population

During the study period, 362 deaths were registered, consisting of 281 (77.6%) in HIV-infected (93.6% HIV-1, and 6.4% HIV-1 and HIV-2 co-infected) and 81 (22.4%) in HIV-uninfected individuals. The demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Women were more represented in the HIV group than in the non-HIV group (p = 0.049). In addition, HIV-infected participants died at a younger age than HIV-uninfected participants (p < 0.001). There was no statistical difference between the median duration of hospitalisation in both groups (p = 0.743).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population.

| HIV infected | HIV uninfected | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 128 (45.6) | 46 (56.8) | 0.0786 |

| Female | 153 (54.4) | 35 (43.2) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 40.23 (11.58) | 55.46 (18.28) | <0.0001 |

| Profession | |||

| Employed | 142 (50.5) | 19 (23.5) | |

| Students | 16 (5.7) | 4 (4.9) | <0.0001 |

| Unemployed | 123 (43.8) | 58 (71.6) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced | 9 (3.2) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Married | 122 (43.4) | 42 (51.6) | 0.0111 |

| Single | 125 (44.5) | 23 (28.4) | |

| Widowed | 25 (8.9) | 15 (18.5) | |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (5–18) | 9 (3–17.5) | 0.743 |

Clinical patterns of diseases and causes of death

Table 2 compares the median duration of symptoms and vital signs within the 24 h following admission and the 24 h preceding death between the two groups of participants. Of 281 HIV-infected subjects, previously known status was documented in 263 (93.6%) records. Overall, the median duration of symptoms was longer in the HIV-infected group (21 days vs. 14 days, p = 0.027). During the first 24 h of hospitalisation, HIV-infected patients had a significantly higher mean temperature (p = 0.003) and mean respiratory rate (p = 0.017) and a lower systolic blood pressure (p < 0.0001) than the HIV-uninfected patients. Within 24 h before death, none of the clinical parameters was significantly different between HIV-infected and uninfected patients. Signs heralding death in both groups were a rising pulse and respiratory rate, a falling systolic blood pressure and mental status.

Table 2.

Mean duration of symptoms and parameters during the 24 h following admission and the 24 h preceding death.

| HIV-infected patients |

HIV-uninfected patients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | p |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 21 | 10-60 | 14 | 4–40 | 0.027 |

| Temperature (℃) | |||||

| Admission | 38.5 | 37.3–39.3 | 37.5 | 36.7–38.5 | 0.003 |

| Before death | 39.0 | 37.8–40.0 | 37.8 | 36.9–38.8 | 0.093 |

| Pulse | |||||

| Admission | 100.0 | 80.0–116.6 | 100.0 | 86.0–109.5 | 0.093 |

| Before death | 110.0 | 96.0–132.0 | 92.0 | 67.0–116.3 | 0.265 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Admission | 110.0 | 95.2–120.0 | 120.0 | 100.0–140.0 | <0.0001 |

| Before death | 100.0 | 90.0–110.0 | 100.0 | 97.0–126.3 | 0.373 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Admission | 60.0 | 60.0–80.0 | 70.0 | 60.0–80.0 | 0.04 |

| Before death | 62.0 | 50.0–75.0 | 60.0 | 52.5–67.5 | 0.629 |

| Respiration rate | |||||

| Admission | 28.0 | 24.0–34.0 | 24.0 | 20.0–28.0 | 0.017 |

| Before death | 40.0 | 28.0–48.0 | 35.0 | 19.8–43.5 | 0.842 |

| Glasgow coma scale | |||||

| Admission | 12.0 | 10.0–13.0 | 11.5 | 11.0–12.0 | 0.732 |

| Before death | 8.0 | 6.0–9.0 | 6.5 | 4.0–9.0 | 0.987 |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days) | 8 | 5–18 | 9 | 3–17.5 | 0.743 |

As shown in Table 3, HIV-infected patients had a median lower haemoglobin level than HIV-uninfected (p < 0.0001) and a lower median white blood cell count (p < 0.0001). There was no difference in platelets count regarding HIV-infected status (p = 0.669). Blood urea nitrogen was higher in HIV-infected patients (p = 0.007) and creatinaemia not significantly different (p = 1.000). Most HIV subjects had evidence of advanced disease: 87.8% (101/115) had CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3, 11.3% (13/115) had CD4 200–499 cells/mm3 and 0.9% (1/115) had CD4 > 500 cells/mm3.

Table 3.

Biological parameters of HIV-infected and -uninfected patients.

| Parameters | HIV-infected patients |

HIV-uninfected patients |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Haemoglobin level (g/dL) | 8.2 | 6.6–10.1 | 10.2 | 7.3–11.6 | <0.0001 |

| MCHC (%) | 34.0 | 32.3–35.9 | 35.3 | 33.0–38.1 | 0.179 |

| WBCC (cells/mm3) | 4500.0 | 2800.0–6575.0 | 10,000.0 | 5175.0–16750.0 | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophils count (cells/mm3) | 2900.0 | 1828.5–4494.0 | 7798.5 | 3424–14,543.75 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocytes count (cells/mm3) | 1000.0 | 545.0–1536.0 | 1750.0 | 901.75–2500.0 | 0.001 |

| Platelets count (103cells/mm3) | 164.0 | 96.5–250.5 | 151.5 | 97.5–263.2 | 0.669 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (g/L) | 0.31 | 0.22–0.54 | 0.45 | 0.30–0.88 | 0.007 |

| Creatinaemia (mg/L) | 11.7 | 9.4–14.9 | 12.5 | 9.8–24.7 | >0.9 |

| AST (IU/L) | 42.0 | 27.0–76.0 | 66.1 | 25.0–162.5 | 0.486 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 28.0 | 16.0–56.6 | 45.0 | 21.4–82.0 | 0.029 |

| γ-GT (IU/L) | 36.5 | 24.2–80.2 | 104.9 | 17.6–354.0 | 0.269 |

| Kaliemia (mEq/L) | 4.2 | 3.6–4.7 | 4.1 | 3.7–4.6 | 0.896 |

| Fasting blood sugar (g/L) | 0.94 | 0.80–1.09 | 0.90 | 0.80–1.11 | 0.401 |

MCHC: mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; WBCC: white blood cell count; AST: aspartate transaminase, ALT: Alanine transaminase; γ-GT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.

The vast majority (77.58%) of HIV-infected subjects were classified as WHO class IV, with the rest being WHO stage III. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, HIV-infected patients were significantly more affected by digestive diseases (p < 0.001), neurological diseases (p < 0.001), respiratory diseases (p < 0.001), skin diseases (p < 0.001) and hematologic diseases (p < 0.001). On the contrary, cardiovascular and urogenital diseases were more frequent among HIV-uninfected patients (all p-value less than 0.001). The most frequent causes of death among HIV-infected patients were AIDS-defining diseases, mostly pleural/pulmonary tuberculosis (34.2%), toxoplasmosis (16.4%), cryptococcal meningitis (14.2%) and Kaposi sarcoma (15.7%). HIV-uninfected patients mostly died as a result of chronic diseases including liver diseases (17.3%), kidney failure (13.6%), congestive heart failure of any cause (11.1%) and stroke (9.9%).

Table 4.

Comparison of patterns of digestive, haematological, skin and urogenital diseases in HIV-infected and -uninfected patients.

| Diseases | HIV-infected patients (n = 281) | HIV-uninfected patients (n = 81) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive diseases | |||

| Enterocolitis | 80 (28.5) | 6 (7.4) | <0.0001 |

| Peritoneal tuberculosis | 16 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 0.0279 |

| Candidiasis | 110 (39.1) | 1 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Acute hepatitis | 2 (0.7) | 5 (6.2) | 0.0072 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 7 (2.5) | 14 (17.3) | <0.0001 |

| Digestive haemorrhage | 5 (1.8) | 2 (2.5) | 0.6558 |

| Hepatoma | 2 (0.7) | 8 (9.9) | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatic disease | 0 (0) | 5 (6.2) | 0.0005 |

| Total cases | 222 | 36 | <0.0001 |

| Hematologic diseases | |||

| Anaemia | 229 (84.3) | 42 (55.6) | <0.0001 |

| Sepsis | 30 (11.7) | 9 (3.2) | >0.9 |

| Tuberculous adenitis | 14 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.0460 |

| Leukaemia | 0 (0) | 8 (9.9) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 0.3117 |

| Total cases | 276 | 61 | <0.0001 |

| Skin diseases | |||

| Kaposi sarcoma | 44 (15.7) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Histoplasmosis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| Bullous skin disease | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0.3979 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (0.7) | 2 (2.5) | 0.2176 |

| Prurigo | 4 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | >0.9 |

| Herpes/zona | 6 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.3446 |

| Condyloma | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Total cases | 58 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| Urogenital diseases | |||

| Infection | 7 (2.5) | 4 (4.9) | 0.2737 |

| Urogenital tuberculosis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| Acute renal failure | 0 (0) | 5 (6.2) | 0.0005 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (0.4) | 6 (7.4) | 0.0006 |

| Total cases | 9 | 15 | <0.0001 |

IRIS: Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Table 5.

Comparison of patterns of neurological, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in HIV-infected and -uninfected patients.

| Diseases | HIV-infected patients (n = 281) | HIV-uninfected patients (n = 81) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological diseases | |||

| Cryptococcosis | 40 (14.2) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 46 (16.4) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Meningoencephalitis | 57 (20.3) | 3 (3.7) | <0.0001 |

| Tuberculous meningitis | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Other bacterial meningitis | 6 (2.1) | 1 (1.2) | >0.9 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 2 (0.7) | 13 (16.1) | <0.0001 |

| Total cases | 155 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory diseases | |||

| Pleural/pulmonary tuberculosis | 96 (34.2) | 5 (6.2) | <0.0001 |

| Pneumopathy | 51 (18.2) | 18 (22.2) | 0.4240 |

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | 9 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0.2169 |

| Candida pneumonia | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| Total cases | 158 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | |||

| Tuberculous pericarditis | 11 (3.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0.3133 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (0.7) | 9 (11.1) | <0.0001 |

| Endocarditis | 0 (0) | 3 (3.7) | 0.0109 |

| Stroke/cerebral haemorrhage | 2 (0.7) | 8 (9.9) | <0.0001 |

| Thromboembolic disease | 3 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1.0000 |

| Total cases | 18 | 22 | <0.0001 |

| Others | |||

| Purulent otitis | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| CMV pharyngitis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| Diabetes complications | 6 (2.1) | 4 (4.9) | 0.2400 |

| Pott's disease | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| IRIS | 15 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0.0280 |

| CMV retinitis | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.5789 |

| Neuropsychiatric encephalopathy | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | >0.9 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0.5912 |

IRIS: immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

HIV treatment

Among the 281 HIV-infected participants, 77 (27.4%) subjects were reported to be on HAART, with a median duration of 30 days (IQ range: 13.0–60.0). All of them were on first-line regimen with 47 (61%) being on Lamivudine-Stavudine-Efavirenz, Zidovudine-Lamivudine-Efavirenz regimen was prescribed for 13 (16.9%) of the subjects and Lamivudine-Stavudine-Nevirapine regimen for 12 (15.6%) of the subjects.

Mortality trend by HIV and non-HIV status

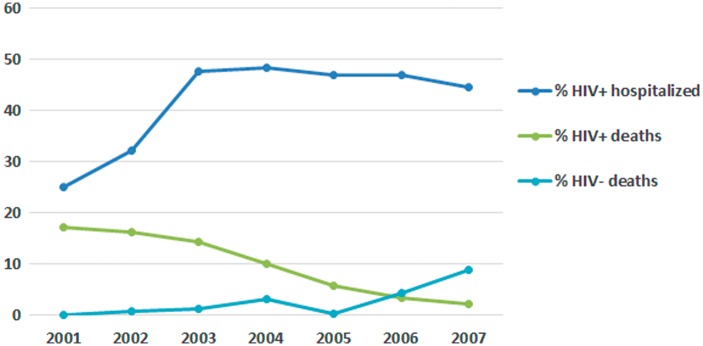

Figure 1 shows the percentage of HIV-infected individuals hospitalised, the percentage of deaths in HIV-infected and -uninfected subjects from January 2000 to May 2007 in the Internal Medicine Ward of the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre. While the proportion of HIV-infected individuals admitted into the unit appeared to be relatively stable, the proportion of deaths in HIV-infected subjects declined and the proportion of deaths in HIV-uninfected individuals was on the rise.

Figure 1.

Hospitalisation and mortality trends by HIV status.

Discussion

In this study, we described the trends in mortality and the spectrum of disease in HIV and HIV-uninfected patients in a population of patients admitted into the Internal Medicine Unit of the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre, a major referral centre in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon. This was a retrospective study of files of deceased patients. Few similar studies are available to conveniently compare with our findings. The disease spectrum is wider in our study. We report on potentially life threatening and associated diseases in more detail in both groups. This is to distinguish the impact of HIV from non-HIV disease. Despite the differences in the study population, diseases included and possible differences in the method of diagnosis, related studies can be compared. No local data are available to compare the mortality trend described in our study.

Our data suggest that mortality due to HIV appears to be declining in a population benefiting from continuous HIV sensitisation and subsidised medical care. Most of those who died of HIV disease had evidence of profound immunosuppression, and most were not on HAART. Treatment time was short in most of those who were on treatment. Tuberculosis and other pneumopathies, meningoencephalitis (toxoplasmosis, cryptococcus and others), diarrhoeal diseases, and associated anaemia were the major reasons for hospitalisation and death. HIV-infected patients died of chronic organic diseases like heart failure, stroke, liver disease, kidney disease and diabetes. As shown in previous studies,2–5,9,12 HIV-infected patients died at a younger age compared to HIV-uninfected patients, and females were disproportionally affected.

We found that on admission, HIV-infected patients were significantly more pyrexical (with higher median body temperature), had lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures and higher respiratory rate. These findings are in keeping with the fact that HIV-infected patients were admitted mostly with severe infectious diseases characterised by signs of severe inflammatory response including pyrexia, tachypnea and low systolic and diastolic blood pressures, as compared to HIV-uninfected patients admitted for chronic non-communicable diseases. Concerning biological parameters, the significantly lower haemoglobin levels seen in HIV-infected patients correlate with the higher frequency of anaemia seen in these patients, likely anaemia of chronic diseases. Because of their immunodepression, HIV-infected patients had significantly lower white cells.

The majority of HIV-infected patients had profound immunosuppression with CD4 counts below 50 cells/mm3, as reported by in previous studies.5,12 This rejects the hypothesis that HIV-infected individuals in Africa die at a relatively earlier degree of immunosuppression because of disease caused by pathogens of high virulence.13 A common finding in these studies is the predominance of tuberculosis, with regional differences in other aspects. All cases of tuberculosis are estimated to be as high as 50%, though a patient might have more than one localisation. It is significantly higher than the 29% and 14% prevalence rates found, respectively, in a group of hospitalised HIV-infected adults in several tertiary hospitals of West Africa (Bamako, Abidjan, Ouagadougou, Cotonou and Dakar) in 2010,5 and in a cohort of hospitalised HIV-infected patients in Abidjan in 1997.12 Unlike a report from South Africa where the frequency of pneumocystis pneumonia was 0.53%,14 cases attributed to pneumocystis pneumonia were not uncommon as 3.2% of HIV-infected patients were affected. All cases of cerebromeningeal infection combined were estimated to be up to 37% or more. This is higher than that reported by other authors.14,15 Bergemann and Karstaeddt16 found that cryptococcal meningitis was less frequent than tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected patients with meningitis in Soweto, a spectrum which is the contrary of what we found in this study, as the frequencies of cryptococcal meningitis and tuberculous meningitis were 14.2% and 1.4%, respectively. Cerebral toxoplasmosis was common as in other studies.5,12 Kaposi sarcoma was more frequent than in other studies,5 and this is probably due to the profound immunosuppression at presentation of HIV-infected patients in our study which is a consequence of lack of access to appropriate and timely healthcare and intervention. A mean duration of symptoms of 53 days before death does not suggest a rapid progression of the disease as suggested by other authors.9,17

Concerning trends in admissions and mortality, we found that, whereas the proportion of HIV-infected individuals admitted into the unit was relatively stable over time, the proportion of deaths in HIV-infected subjects declined and the proportion of deaths in HIV-uninfected individuals was on the rise. This progressive reduction of the proportion of AIDS-related deaths is most probably the result of the different interventions conducted by healthcare providers to tackle the burden of HIV/AIDS, especially the introduction of HAART.

Our study has some limitations. We could not rule out the possibility of missing data, which could alter the trend in mortality reported. Postmortem examinations were not features of our study. This would have improved the diagnoses.

Conclusion

This study shows that HIV-associated mortality is declining with appropriate and timely interventions such as reduced test costs, more decentralised treatment centres and free antiretroviral treatment and related medications. The spectrum of disease is wide and preventable. To prolong healthy life at large, such interventions should be scaled up nationwide.

Acknowledgements

None

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Contributorship

Study conception and design: JM, AMJ; Data collection: AMJ; Data analysis and interpretation: AMJ, JJNN; Manuscript drafting: JJNN, AMJ, AK; Critical revision of the manuscript: JM, AMJ, JJNN, AK, JRNN, JJRB, EWY, KNB.

Guarantor

AMJ

Ethical approval

Institutional review board of the Yaoundé University Hospital Centre.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by José Arellano-Galindo

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. 2013. , www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf (2013, accessed 27 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkhof MW, Boulle A, Weigel R, Messou E, Mathers C, Orrell C, et al. Mortality of HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: comparison with HIV-unrelated mortality. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000066–e1000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldaz P, Moreno-Iribas C, Egüés N, Irisarri F, Floristan Y, Sola-Boneta J, et al. Mortality by causes in HIV-infected adults: comparison with the general population. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 300–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008; 22: 1897–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewden C, Drabo YJ, Zannou DM, Maiga MY, Minta DK, Sow PS, et al. Disease patterns and causes of death of hospitalized HIV-positive adults in West Africa: a multicountry survey in the antiretroviral treatment era. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17: 18797–18797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Cock KM, Barrere B, Diaby L, Lafontaine MF, Gnaore E, Porter A, et al. AIDS: the leading cause of adult death in the West African city of Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Science 1990; 249: 793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulder DW, Nunn AJ, Kamali A, Nakiyingi J, Wagner H, Kengeya-Kayondo J. Two year HIV-1 associated mortality in a Ugandan rural population. Lancet 1994; 343: 1021–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuun AJ, Mulder DW, Kamali A, Ruberantwari A, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Whitworth J. Mortality associated with HIV-1 infection over five years in a rural Ugandan population: cohort study. BMJ 1997; 315: 767–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sewankambo NK, Gray RH, Ahmad S, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, Nalugoda F, et al. Mortality associated with HIV infection in Rural Rakai District, Uganda. AIDS 2000; 14: 2391–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, Kirk O, Reiss P, d’Arminio Monforte A, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EUROSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet 2003; 362: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant AD, Djomand G, Smets P, Kadio A, Coulibaly M, Kakou A, et al. Profound immunosuppression across the spectrum of opportunistic disease among hospitalized HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS 1997; 11: 1357–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilks CF. The clinical challenge of the HIV epidemic in the developing world. Lancet 1993; 342: 1037–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbett EL, Churchyard GJ, Charalambous S, Samb B, Moloi V, Clayton TC, et al. Morbidity and mortality in South African gold miners: impact of untreated HIV disease. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 1251–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyderman RS, Gangaidzo IT, Hakim JG, Mielke J, Taziwa A, Musvaire P, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Harare, Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26: 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergemann A, Karstaeddt AS. The spectrum of meningitis in a population with high prevalence of HIV disease. QJM 1996; 89: 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan D, Maude GH, Malamba SS, Okongo MJ, Wagner HU, Mulder DW, et al. HIV-1 disease progression and AIDS-defining disorders in rural Uganda. Lancet 1997; 142: 1221–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]