Summary

This literature review assesses the current knowledge about the immunological aspects of the vermiform appendix in health and disease. An essential part of its immunological function is the interaction with the intestinal bacteria, a trait shown to be preserved during its evolution. The existence of the appendiceal biofilm in particular has proved to have a beneficial effect for the entire gut. In assessing the influence of acute appendicitis and the importance of a normally functioning gut flora, however, multiple immunological aspects point towards the appendix as a priming site for ulcerative colitis. Describing the immunological and microbiotical changes in the appendix during acute and chronic inflammation of the appendix, this review suggests that this association becomes increasingly plausible. Sustained by the distinct composition of cells, molecules and microbiota, as well as by the ever more likely negative correlation between the appendix and ulcerative colitis, the idea of the appendix being a vestigial organ should therefore be discarded.

Keywords: appendix, biofilm, immunology, inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

Until recently, the human appendix has been regarded as a rudimentary part of the intestine. During the past few years, however, several studies have suggested its immunological importance for the development and preservation of the intestinal immune system 1. The appendix has been shown to have an important interaction with the intestinal flora 2, 3, 4. Considering the appendix as a ‘safe house’ for the commensal gut flora, these studies hypothesize that commensal bacteria can be reintroduced from the appendix in case of disease, and therefore the appendix can be considered as an important part of intestinal health. This literature review assesses the current knowledge concerning the immunological aspects of the vermiform appendix. By describing its normal physiology and the importance of its biofilm, and appraising its evolution and elucidating which aspects have changed or, more importantly, which have been preserved in the long history of its existence, a clearer understanding of its influence on the intestinal immune system will be provided.

The evolutionary perspective

In attempting to discover a plausible function of the human appendix, there has been a search for homology with that of other mammalians. The fact that the appendix is much larger in certain ‘lower’ mammalians such as rabbits has, for a long time, resulted in the human appendix being considered a vestigial organ. The lack of a clear morphological caecal appendage in some evolutionarily more closely related primates, however, seems to contradict this hypothesis 5.

In the assessment of its evolution, the human appendix is generally considered as a remnant of the mammalian caecum. Originally, this part of the intestine had a digestive function, primarily facilitating the digestion of cellulose with the aid of residential micro‐organisms 6. This cellulose digestive trait is lost in the human caecum, although in the human appendix a relative abundance of micro‐organisms present in biofilms still exists alongside the presence of lymphoid tissue 3. The vermiform appendix in rabbits is found to be essential for the development of the gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). After the initial independent development of follicle centres, presence of the commensal intestinal flora is required for diversification of the primary antibody repertoire and for further development of T and B cell areas of follicles within the lymphoid tissue 7, 8, 9. In some non‐human primates, such as tamarins and white‐eyelid mangabeys 5, and other mammals such as mice 10 and rats 11 that lack a caecal diverticulum, a high concentration of lymphoid tissue is found in the caecal apex 5, referred to as the ‘caecal patch’. Moreover, the proximal large bowel of amphibians and reptiles, that lack both the presence of a caecum and appendix and the need of cellulose digestion, also functions as the site where most of the interaction between host and symbiotic bacteria is seen 12. This gives rise to the idea that the appendix, with its excellent conditions for sheltering the commensal gut flora, may have evolved prior to the caecum, rather than having derived from it. Therefore, the digestive trait could have been developed in conjunction with the bulging of the proximal large intestine that eventually became the caecum, which would imply that the immunological function existed before the digestive one. The worm‐like morphology of the appendix and its location in the gut could indicate its long‐lasting immunological function by providing a ‘safe house’ for the commensal intestinal flora, instead of being evidence for its vestigial nature 3, 12.

Functional histology of the appendix

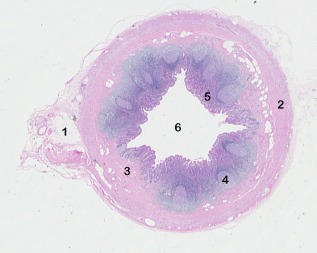

Similar to the intestinal wall of the colon, the appendiceal wall consists of a mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa and serosa (Fig. 1). Within these layers, however, the presence, quantity and function of cells differ between the appendix and colon, illustrated most notably by the presence of lymphoid follicles in the submucosa and lamina propria of the appendiceal wall 13. The characteristics of cells and molecules found in human appendix are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Transverse section of a healthy adult appendix. 1, mesoappendix; 2, muscularis externa; 3, submucosa; 4, lymphoid follicle; 5, mucosa and 6, lumen.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cells and molecules found in human appendix.

| Quantity compared to colon | Localization | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD5 14, 15 (B1 cells) | Increase | – | Production anti‐microbial IgM Antibodies and anti‐self‐antibodies |

| CD19 14 | Increase | – | B cell co‐receptor |

| CD4CD69 16 | Increase during UC | Mucosa | Early activation of T cells |

| CCL21 17 | Increase | Parafollicular areas | Attraction CCR7‐expressing cells (T and B lymphocytes and DCs) |

| FoxP3 18 | Increase during appendicitis | Lamina propria | Regulatory immune response |

| IELs 19, 20, 21 | Increase | (Dome) epithelium | Innate‐like and adaptive immune response |

| α4β7 22 | Increase (β7) | T cells between lamina propria and epithelium, macrophages | Gut‐homing |

| αΕβ7 22 | Increase (β7) | Mucosal CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells | Cellular retention in mucosa |

| IgG 1, 23, 24 | Increase | Lamina propria | Agglutination and opsonization of pathogens, complement activation |

| sIgA 4, 25, 26 | Increase | Mucosa | Agglutination of bacteria |

| Mucin 4, 25, 26 | Increase | Mucosa | Formation intestinal mucus layers Aiding formation biofilm by binding bacteria to mucus layer |

Ig = immunoglobulin; UC = ulcerative colitis; DCs = dendritic cells; FoxP3 = forkhead box protein 3.

Mucosa

The mucosa consists of columnar epithelium with enterocytes and goblet cells, a lamina propria and a muscularis mucosae. Next to macrophages, an abundance of immunoglobulin (Ig)A‐ or IgG‐producing plasma cells is found in the lamina propria. Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) in the appendix consist mainly of small CD8+ regulatory T (Treg) cells 19, comparable with their presence in the epithelium of the colon. In the dome epithelium, also known as follicle‐associated epithelium, which is located above the lymphoid follicles, the number of these IELs is increased to the rest of the appendiceal and colonic epithelium. Instead of only small Treg cells, M cells 27, 28, 29 and human leucocyte antigen D‐related (HLA‐DR) bearing T and B cells 20 are also found here. As their presence is a sign of antigen transportation from the lumen and antigen presentation, respectively, it could indicate that the dome epithelium is an area of immune stimulation. Some of the IELs are morphologically similar to the cells in the follicle centre, giving rise to the speculation that IELs could, at least partly, have their origin in these follicles. Crypts of Lieberkühn are present in the appendix, similar to the colon. Paneth cells, normally found in the small intestine, are found at the bottom of these crypts 30, with the production of anti‐microbial peptides as their main function 31.

Submucosa

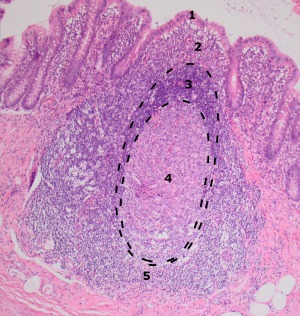

Submucosa consists of connective tissue and is characterized by the presence of many lymphoid follicles that extend from the submucosa into the lamina propria (Fig. 2). While their presence or an equivalent structure is not seen in a healthy colon, they are comparable to Peyer's patches in the small intestine. The mantle zone of this lymphoid tissue, which is localized predominantly nearest to the lumen, contains densely packed B lymphocytes and few T lymphocytes. The dark zone within the distinct germinal centre is localized farthest from the lumen. It contains macrophages and centroblasts, proliferating B cells that give rise primarily to the follicle by monoclonal expansion. Centrocytes are derived from these centroblasts, and form the light zone together with follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) 32. FDCs activate centrocytes by antigen presentation, which stimulates the production of immunoglobulins and prolongs their lifespan. Following CD40‐CD40L interaction with T cells, centrocytes can also differentiate into plasmablasts or memory B cells 33, 34. Between the dome epithelium and lymphoid follicles another distinct area of immune cells is found: the mixed cell zone, consisting of macrophages and lymphocytes, B as well as T cells 20. At the bottom of the lymphoid follicles are T cell areas, containing macrophages and T cells, with eightfold times more CD4+ than CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2.

Appendiceal lymphoid follicle. Indicated are the distinctive areas of its most important constituents. 1, Dome epithelium: intra‐epithelial lymphocytes; 2, mixed cell zone: T‐lymphocytes, B‐lymphocytes, macrophages; 3, mantle zone: small B‐lymphocytes; 4, Germinal centre: centroblasts, centrocytes, follicular dendritic cells, macrophages; 5, T‐cell area: T‐lymphocytes, macrophages.

Lymphocytes in the appendiceal tissue

The appendix has a distinct abundance of natural killer (NK)1·1+ CD3+ T cells (NK T lymphocytes), that can produce cytokines and chemokines rapidly following activation. Also the presence of B220+CD3+ T cells, T cells expressing CD45R indicative for their activation, is increased compared to the rest of the gut 35. A contributing factor to the abundance of lymphocytes may be the presence of CCL21, a chemokine present on the luminal surface of high endothelial venules and on lymphatic endothelial cells in parafollicular areas. By its binding to CCR7, CCL21 promotes the recruitment of B and T lymphocytes to the appendiceal lymphoid tissue and the migration of activated dendritic cells (DCs) back to lymph nodes 17, 36.

Apart from the unique lymphocyte content of the appendix, difference is also found in molecules expressed on their surface when compared to the expression profile of intestinal lymphocytes. T cells in the lamina propria express more of the integrin subunit β7 compared to B cells in lamina propria and T and B cells throughout other parts of the gut. Integrin α4β7 is present primarily on T cells between lamina propria and epithelium, and on macrophages αΕβ7 mainly on mucosal CD8+ T cells and DCs 22. α4β7 binds to mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM‐1), with this interaction mediating the ‘tethering and rolling’ or ‘homing’ step in the attraction of lymphocytes. Because of the localization of its expression, α4β7 could therefore be regarded as a trafficking signal. Conversely, αΕβ7 is responsible for the retention of these lymphocytes, via binding with its ligand E‐cadherin 37. Intestinal DCs expressing αΕβ7 are believed to stimulate differentiation of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3)+ Treg cells after encountering (antigens of) bacteria. Logically, suppressing this differentiation into regulatory lymphocytes could lead to a proinflammatory state 21.

Interaction with microbial flora

The intestinal biofilm

The most luminal lining of the large intestinal wall contains the biofilm, a layer of commensal gut bacteria within a matrix of mucus that is believed to aid immune exclusion of pathogens by preventing them from crossing the intestinal barrier. The layer of thick, firm mucin that lays directly upon the intestinal epithelial cells is insoluble, thus preventing (pathogenic) bacteria from being in contact with the epithelium 38. On top of this firm layer and directly adjacent to the lumen is a layer of looser mucin and commensal gut bacteria, together forming the biofilm 39, 40. In addition to the direct barrier function of the firm inner mucus layer, immune exclusion of potential pathogens could also be an indirect effect of the inclusion of microbiota in the biofilm, as bacteria within a biofilm are less likely to cross the epithelial barrier compared to single, planktonic bacteria 4, 25.

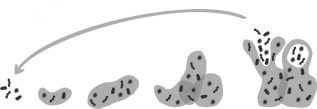

Apart from mechanical barrier formation, biofilms shed bacteria actively from their surface. Shedding of planktonic bacteria could be seen as the mechanism behind immune exclusion of pathogens throughout the whole large intestine. Conversely, the shedding of parts of the biofilm itself is rather believed to facilitate (re)colonization of beneficial bacteria 41, 42 (Fig. 3). This could be a function carried out exclusively by the appendix, as it is believed to be the only place within the large intestine that has not been cleared from its normal biofilm after diarrhoeal illness. During diarrhoea, turnover of enterocytes and thus shedding of the biofilm is accelerated 43, thereby leaving the intestinal wall derived of its protective barrier.

Figure 3.

The process of biofilm formation, shedding and recolonization. Bacteria adhere to the surface. Biofilm formation and expansion by embedding bacteria within the mucin layer. Parts of the biofilm shed, which allows bacteria to relocate and recolonize (adapted from reference 42).

In contrast to the suggested induction of biofilm shedding by pathogens during acute diarrhoeal illness, diarrhoea‐inducing infectious agents actually enhance mucin gene expression 44, 45. This enhancement, mediated particularly by cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α 44, may indicate a stronger binding instead of an easier shedding. This could be seen as a reaction to the disruption of the mucus layers following bacterial invasion, but the definite function has not been determined. However, during an infection the intestinal wall shows an increase in goblet cells and mucus secretion compared to the healthy situation, which may explain the enhanced mucin gene expression. As this is associated with a better clearance of the pathogen 39, whether by speeding up the mucus turnover or creating a thicker layer, it could be seen as a defence mechanism against the infection.

Special role for the appendiceal biofilm

The protected location in the most proximal part of the colon and its relatively little contact with faeces because of this location, and its narrow (worm‐like) lumen, have given rise to the assumption that the appendiceal lumen is spared from the diarrhoeal clearance. Thus, the biofilm in the appendix is thought to act as a ‘safe house’ for commensal bacteria and to facilitate their reinoculation of the gut after a gastrointestinal infection 2, 3, 4. Secretory IgA (sIgA) and mucin assist in biofilm formation by increasing adhesive growth of the agglutinated gut flora 4, 25, 26, as sIgA stimulates the agglutination of bacteria and mucin binds these bacteria to the mucus layer. In the appendix, there is an overall high density of mucin and sIgA produced by B cells in the mucosa. Thus, the outer loose mucus layer of the appendix has a promicrobiotic environment, once again supporting its function as a ‘safe house’ 4.

Furthermore, the presence of commensal bacteria in neonatal intestines of mice causes an immune reaction by stimulating B cells in germinal centres to produce antibodies, thereby assuring a normal development of the immune system 46. In humans, timing of the development of lymphoid follicles is consistent with the presence of bacteria in gut mucosa, both of which occur after the first 4 weeks postnatally 1.

The intestines of germ‐free animals show a decrease in IELs, IgA levels and lamina propria lymphocytes 47, an impaired maturation of lymphocyte aggregates into isolated lymphoid follicles or Peyer's patches 48, 49 and smaller germinal centres 49 caused possibly by the absence of proliferating B cells 50. As the immune function within the intestine is otherwise impaired, it is therefore suggested that interaction with the commensal flora helps the GALT in developing an adequate immune response to pathogens 1, 25, 48, 49. Considering the high density of bacteria in the appendix and its assumed function as a ‘safe house’, it could indicate that the appendiceal biofilm has a crucial immunological role in aiding the development of a normal (intestinal) immune system.

Characteristic appendicular changes in inflammatory bowel disease

Acute appendicitis

Typical histological characteristics of acute appendiceal inflammation are mucosal ulceration 51, transmural infiltration of neutrophils and eventually perforation and serositis. In a more chronic stage of the appendiceal inflammation, infiltration of lymphocytes is observed 18, 52. Murine studies show an increase in the quantity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and a higher amount of FoxP3+CD25+ T cells in acutely inflamed appendices. FoxP3+CD25+ cells have a regulatory function, but they have been shown to be increased only in young mice and in the absence of anti‐microbial substances such as antibiotics 18. Regulation of inflammation occurs when FoxP3+CD25+ cells suppress IELs that are providing a protective function themselves, thus decreasing their production of cytokines and thereby tempering inflammation 21.

CD5+ cells, also known as B1 lymphocytes, are found to a greater extent in healthy appendices compared to the rest of the gut, but even more so in inflamed specimens 14. These CD5+ B cells produce IgM antibodies against a broad range of pathogens. Antibody production takes place initially in the absence of antigen presentation by T cells, resembling an innate‐like immune response such as that expressed by IELs 43. Although these IgM antibodies have no high antigen affinity, they may still be important in first reaction to micro‐organisms. Their increase could be explained by the simultaneous alteration in composition of the gut flora during acute appendicitis. Additionally, CD5+ B cells also produce anti‐self antibodies and the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10, thereby being of influence in autoimmune diseases 14, 53.

Ulcerative colitis

In contrast to the transmural histological changes during appendicitis, a more chronic and autoimmune co‐ordinated inflammation of the appendix is seen in ulcerative colitis (UC). A distinct increase in the occurrence of Paneth cell differentiation, goblet cell depletion and crypt abscesses is observed, while neutrophil infiltration is not prominent. This resembles colonic inflammation in UC rather than a ‘normal’ acute appendicitis, suggesting it to be a skip lesion of UC instead of a concurrent disease 54, 55. In fact, appendiceal orifice inflammation in UC is not exceptional, and is not seen solely in right‐sided or pancolonic UC, but also in mild disease restricted otherwise to the left colon or rectum 56. Additionally, in some cases an appendiceal orifice inflammation even precedes UC, suggesting that it may play a role in its development 57. The appendiceal inflammation is confined predominantly to the mucosa and results in both a quantitative and qualitative change of the lymphocyte phenotype, with an increased ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ in T lymphocytes, because it is predominantly the early activation antigen CD69 in T lymphocytes 16, 58 and the activation marker CD25 in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes 54 that are increased in UC. This could indicate that the appendix acts as an early priming site for this particular disease, that becomes activated before the rest of the colon.

Immunological link between acute appendicitis and ulcerative colitis

The pathway by which appendectomy seems to relatively protect patients against the development of UC 55, 59, 60 is not yet clear, but age at time of intervention 61 and use of antibiotics during treatment of acute appendicitis 62 have proved to be of influence. The protection against the development of UC by the combination of appendicitis and appendectomy suggests that characteristic immunological processes make the appendix a priming site for UC 16, 58, 63. Possibly FoxP3+CD25+ T cells, CD5+ and CD19+ B cells play a special role, which will be elaborated further below.

The increase in regulatory FoxP3+CD25+ T cells during appendicitis could initiate a regulatory immune response able to prevent autoreactivity, as is seen in UC. Age has proved to be the major limitation on the stimulation of FoxP3+CD25+ T cells in mice 18, just as the protective mechanism of appendectomy is achieved only when patients have undergone surgery before the age of 20 years. This similarity, that has not been found for other markers, makes it plausible that FoxP3 plays a certain role in the incitement of ulcerative colitis. The need for the absence of anti‐microbial substances in order for FoxP3+CD25+ T cells to increase during appendicitis could indicate its crucial function in the intestinal response against bacteria. Their regulatory immune reaction could mean a lower to non‐existing response to (commensal) bacteria in the colon, in contrast to the uncontrolled reaction that would normally take place at the incitement of UC 18. Although data are not available for the appendix, the presence of regulatory T cells in colonic lamina propria during UC has been explored. One study shows a decrease of regulatory T cells 64, which would be in line with the presumed defect in UC. Yet another demonstrates a contradictory increase in FoxP3+CD25+ T cells in colonic lamina propria during UC 65. If this proved to be the same in the appendix, it would indicate that the increased amount of FoxP3+CD25+ T cells is not enough to regulate the ongoing inflammation. Nevertheless, it does not rule out the possibility of preventing UC before its onset.

CD5+ B lymphocytes have been shown to be increased in acute appendicitis. In UC, however, the number of these cells is decreased, and with it also decreasing the quantity of natural antibodies and anti‐self‐antibodies. This could indicate that the presence of CD5+ B cells has a protective role against UC. If so, it would only be expected that a period in life in which there is a relatively high concentration of CD5+ lymphocytes, as is the case in acute appendicitis, could have a beneficial protective effect against UC 53.

The percentage of CD19+ B cells is increased in healthy appendices compared to the rest of the gut, but this increase is even more profound in inflamed specimens 14. CD19 is a common marker present on all B cells. It acts as a co‐stimulatory molecule important for the survival, maturation and function of B cells 66. The higher percentage of CD19+ B lymphocytes, with their function in prosurvival signalling, could point towards the appendix being a site meant specifically for maturation and activation for B cells. Because the increase in CD19 during inflammation could actually be considered as an amplification of the already high preinflammatory status, this may even be an indication of the appendix being a priming site in UC.

Murine studies linking the appendix to ulcerative colitis

Various murine studies support the idea that the appendix may be of importance in the pathogenesis of UC. Despite the fact that mice lack a vermiform appendix, as mentioned earlier, they have a caecal patch that is considered the equivalent of the human appendix. A study analysing the migration of colitis‐inducing CD62L+CD4+ cells showed a 3·5‐fold enhanced migration of these cells into the caecal patch compared to the colon. Inflammation in this model was more profound in the distal colon, suggesting that the appendix serves as a site to store and prime the colitis‐inducing CD62L+CD4+ cells 67. Furthermore, appendectomy (i.e. removal of the caecal patch) in several murine models with experimental colitis was shown to protect against the development of colitis. In experiments with T cell receptor‐alpha mutant mice that develop inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) spontaneously, appendectomy at a young age (< 5 weeks) suppressed the development of colitis, whereas 80% of the sham‐operated mice developed IBD 68. In another study where colitis was induced with dextran sulphate sodium (DSS), mice that had undergone appendectomy showed a delayed onset of colitis and a milder disease activity 69. These murine models, by describing the effect of appendectomy, could imply an important role for the appendix in the pathogenesis of UC.

Intestinal mucus layer and microbial flora in ulcerative colitis

Both the inner firm and outer loose mucus layer discussed earlier are likely to play a role in the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. Mice with a deficient mucus layer show a different response when colitis is induced with DSS 70. Defects in the inner layer, in particular, leading to penetration of the luminal bacteria, are thought to play a role in the initiation of UC 39. The absence of MUC2, a subtype within the mucin family that is essential for the renewal and formation of the mucus layer, has been shown to lead to spontaneous inflammation 40 and to colon cancer in the long term 38, 39, a process completely in accordance with the disease course of UC 71. Whereas during acute (infectious) colitis an increase in goblet cells and mucus secretion is observed, correlating with a better clearance of the pathogen thus aiding recovery 39, the appendiceal goblet cell population is depleted in UC 54. Whether this depletion and defective mucus layer are cause or effect of UC is still being questioned 72. However, it would be interesting to speculate that it precedes aberrant interaction with the gut flora leading to the inflammation, because this would again present the appendix as a possible priming site, given its rich bacterial content.

Although dysbiosis is often seen during UC, there is no distinct composition of gut flora during UC 66, as the dysbiosis is variable in individuals 73. Until now, no bacteria are found that are correlated strongly with (the onset of) UC besides a suggested possible causal relation with Fusiform varium 74. Studies examining the effect of antibiotic or probiotics in IBD patients 21, 66, 73, 75, 76 have inconsistent and disappointing results, which may be explained by this wide variation of gut flora composition in UC patients.

Genetic and anti‐microbial influences

It is stated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in triggering IBD, with a total of 200 IBD risk loci identified through genome‐wide association studies 77, 78. As the increase in the incidence of IBD in the western world since the 19th century is too rapid to be attributed only to genetic risk factors, it is argued that genetic susceptibility is particularly relevant in combination with environmental factors 78, 79. It has been suggested that this observed trend may be explained by the hygiene hypothesis. In essence, the hygiene hypothesis argues that a lower infection rate is the underlying cause of the increasing incidence of autoimmune diseases such as UC because of the lack of protection against immunological disorders carried out by certain infectious agents 80. Proponents reason that anti‐infectious factors such as use of antibiotics, vaccinations and the relatively uncontaminated western diet can influence the intestinal microbiome. The lower exposure to pathogens causing this alteration could lead eventually to a dysbiosis which, in turn, could induce or perpetuate abnormal immune reactivity, as is seen in UC 81. However, recent studies demonstrated no statistically significant association for most hygiene‐related risk factors in residents of fully developed western countries 79, 82, but discovered these factors to be still influential in migrants moving from low‐ to high‐incidence countries 79. The only consistent association among hygiene‐related environmental factors is reported between antibiotic use in childhood and an increase in incidence of IBD 62, 79, 83. This association could be explained by mechanisms described earlier: as appendicitis is believed to induce a regulatory immune response, anti‐microbial treatment treating the inflammation would consequently interfere with this effect. Indeed, in mice suffering from acute appendicitis that were treated with antibiotics, the percentage of FoxP3+ Treg cells of the total CD8+ cells was observed to be decreased to a nearly normal level. In mice without the anti‐microbial treatment, this percentage was more than twice as high 18.

Conclusion

The vermiform appendix is not a rudimentary organ, but rather an important part of the immune system with a distinct function within the GALT different from lymphoid tissue in other parts of the intestine. Having examined the evolutionary characteristics, it can be deduced that the core function in origin lays in the interaction with and the handling of intestinal bacteria. It influences GALT by stimulating its development and aids recovery after diarrhoeal illness by recolonizing the colon with commensal flora.

The observations elaborated in this review support the idea that a defective function and interaction with gut flora in the appendix play an essential role in the aetiology and probably also in the onset of UC. However, it remains uncertain whether the dysbiosis seen in appendices of many UC patients is the cause or result of the inflammation. Based on this, it can be concluded that the appendix has an important immune function both in health and disease. There are, however, numerous interesting aspects left unstudied. Progress could be made in understanding the influence of the appendix on the development of GALT and on normally functioning gut flora. Further research should focus upon identification of causal bacteria associated with UC within the appendix, which might improve health care by earlier detection of the disease and amelioration of treatment.

Disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1. Gebbers JO, Laissue JA. Bacterial translocation in the normal human appendix parallels the development of the local immune system. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004; 1029:337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Im GY, Modayil RJ, Lin CT et al The appendix may protect against Clostridium difficile recurrence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:1072–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laurin M, Everett ML, Parker W. The cecal appendix: one more immune component with a function disturbed by post‐industrial culture. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2011; 294:567–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Randal Bollinger R, Barbas AS, Bush EL, Lin SS, Parker W. Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J Theor Biol 2007; 249:826–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fisher RE. The primate appendix: a reassessment. Anat Rec 2000; 261:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kardong K. Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution, 6th edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lanning D, Sethupathi P, Rhee KJ, Zhai SK, Knight KL. Intestinal microflora and diversification of the rabbit antibody repertoire. J Immunol 2000; 165:2012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanson NB, Lanning DK. Microbial induction of B and T cell areas in rabbit appendix. Dev Comp Immunol 2008; 32:980–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhai SK, Lanning DK. Diversification of the primary antibody repertoire begins during early follicle development in the rabbit appendix. Mol Immunol 2013; 54:140–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swidsinski A, Loening‐Baucke V, Lochs H, Hale LP. Spatial organization of bacterial flora in normal and inflamed intestine: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study in mice. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:1131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palestrant D, Holzknecht ZE, Collins BH, Parker W, Miller SE, Bollinger RR. Microbial biofilms in the gut: visualization by electron microscopy and by acridine orange staining. Ultrastruct Pathol 2004; 28:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith HF, Fisher RE, Everett ML, Thomas AD, Bollinger RR, Parker W. Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. J Evol Biol 2009; 22:1984–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ross MH, Pawlina W. Histology: a text and atlas with correlated cell and molecular biology, 6th edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Somekh E, Serour F, Gorenstein A, Vohl M, Lehman D. Phenotypic pattern of B cells in the appendix: reduced intensity of CD19 expression. Immunobiology 2000; 201:461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayakawa K, Hardy RR. Development and function of B‐1 cells. Curr Opin Immunol 2000; 12:346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsushita M, Takakuwa H, Matsubayashi Y, Nishio A, Ikehara S, Okazaki K. Appendix is a priming site in the development of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:4869–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagira M, Imai T, Yoshida R et al A lymphocyte‐specific CC chemokine, secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC), is a highly efficient chemoattractant for B cells and activated T cells. Eur J Immunol 1998; 28:1516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watson Ng WS, Hampartzoumian T, Lloyd AR, Grimm MC. A murine model of appendicitis and the impact of inflammation on appendiceal lymphocyte constituents. Clin Exp Immunol 2007; 150:169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deniz K, Sokmensuer LK, Sokmensuer C, Patiroglu TE. Significance of intraepithelial lymphocytes in appendix. Pathol Res Pract 2007; 203:731–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spencer J, Finn T, Isaacson PG. Gut associated lymphoid tissue: a morphological and immunocytochemical study of the human appendix. Gut 1985; 26:672–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith P, MacDonald T, Blumberg R, eds. Principles of mucosal immunity. New York: Garland Science, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Farstad IN, Halstensen TS, Lien B, Kilshaw PJ, Lazarovits AI, Brandtzaeg P. Distribution of beta 7 integrins in human intestinal mucosa and organized gut‐associated lymphoid tissue. Immunology 1996; 89:227–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bjerke K, Brandtzaeg P, Rognum TO. Distribution of immunoglobulin producing cells is different in normal human appendix and colon mucosa. Gut 1986; 27:667–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen ST. Cellular sites of immunoglobulins. II. The relative proportions of mucosal cells containing IgG, IgA, and IgM, and light polypeptide chains of kappa and lambda immunoglobulin in human appendices. Acta Pathol Jpn 1971; 21:67–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Everett M, Palestrant D, Miller S, Bollinger R, Parker W. Immune exclusion and immune inclusion: a new model of host‐bacterial interactions in the gut. Clin Appl Immunol Rev 2004; 4:321–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bollinger RR, Everett ML, Palestrant D, Love SD, Lin SS, Parker W. Human secretory immunoglobulin A may contribute to biofilm formation in the gut. Immunology 2003; 109:580–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Uchida J. Electron microscopic study of microfold cells (M cells) in normal and inflamed human appendix. Gastroenterol Jap 1988; 23:251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Owen RL, Nemanic P. Antigen processing structures of the mammalian intestinal tract: an SEM study of lymphoepithelial organs. Scanning Electron Microsc 1978; 2:367–78. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corr SC, Gahan CC, Hill C. M‐cells: origin, morphology and role in mucosal immunity and microbial pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2008; 52:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Junqueira L, Carneiro J. Basic histology: text and atlas, 11th edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill Medical, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duggan C, Watkins J, Walker W. Nutrition in pediatrics: basic science and clinical applications, 4th edn. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tarlinton D. Germinal centers: form and function. Curr Opin Immunol 1998; 10:245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacLennan IC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12:117–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tarlinton DM, Smith KG. Dissecting affinity maturation: a model explaining selection of antibody‐forming cells and memory B cells in the germinal centre. Immunol Today 2000; 21:436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ishimoto Y, Tomiyama‐Miyaji C, Watanabe H et al Age‐dependent variation in the proportion and number of intestinal lymphocyte subsets, especially natural killer T cells, double‐positive CD4+ CD8+ cells and B220+ T cells, in mice. Immunology 2004; 113:371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Comerford I, Harata‐Lee Y, Bunting MD, Gregor C, Kara EE, McColl SR. A myriad of functions and complex regulation of the CCR7/CCL19/CCL21 chemokine axis in the adaptive immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2013; 24:269–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gorfu G, Rivera‐Nieves J, Ley K. Role of beta7 integrins in intestinal lymphocyte homing and retention. Curr Mol Med 2009; 9:836–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin‐dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:15064–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johansson ME, Sjovall H, Hansson GC. The gastrointestinal mucus system in health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johansson ME. Fast renewal of the distal colonic mucus layers by the surface goblet cells as measured by in vivo labeling of mucin glycoproteins. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e41009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin‐Scott HM. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol 1995; 49:711–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abelson M, McLaughlin J. Of biomes, biofilm and the ocular surface. Rev Opthalmol 2012; 19:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murphy K, Travers P, Janeway C, Walport M. Janeway's immunobiology, 7th edn. New York: Garland Science, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Radhakrishnan P, Halagowder D, Devaraj SN. Altered expression of MUC2 and MUC5AC in response to Shigella infection, an in vivo study. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1770:884–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vieira MA, Gomes TA, Ferreira AJ, Knobl T, Servin AL, Lievin‐Le Moal V. Two atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains induce the production of secreted and membrane‐bound mucins to benefit their own growth at the apical surface of human mucin‐secreting intestinal HT29‐MTX cells. Infect Immun 2010; 78:927–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cebra JJ. Influences of microbiota on intestinal immune system development. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69:1046S–1051S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S et al Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science 2012; 336:489–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chinen T, Rudensky AY. The effects of commensal microbiota on immune cell subsets and inflammatory responses. Immunol Rev 2012; 245:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rhee KJ, Sethupathi P, Driks A, Lanning DK, Knight KL. Role of commensal bacteria in development of gut‐associated lymphoid tissues and preimmune antibody repertoire. J Immunol 2004; 172:1118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lamps LW. Infectious causes of appendicitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2010; 24:995–1018, ix–x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carr NJ. The pathology of acute appendicitis. Ann Diagn Pathol 2000; 4:46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Polese L, Boetto R, De Franchis G et al B1a lymphocytes in the rectal mucosa of ulcerative colitis patients. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jo Y, Matsumoto T, Yada S et al Histological and immunological features of appendix in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 2003; 48:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scott IS, Sheaff M, Coumbe A, Feakins RM, Rampton DS. Appendiceal inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Histopathology 1998; 33:168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Park SH, Loftus EV Jr, Yang SK. Appendiceal skip inflammation and ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 2014; 59:2050–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Park SH, Yang SK, Kim MJ et al Long term follow‐up of appendiceal and distal right‐sided colonic inflammation. Endoscopy 2012; 44:95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matsushita M, Uchida K, Okazaki K. Role of the appendix in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Inflammopharmacology 2007; 15:154–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Florin TH, Pandeya N, Radford‐Smith GL. Epidemiology of appendicectomy in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: its influence on the clinical behaviour of these diseases. Gut 2004; 53:973–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gardenbroek TJ, Eshuis EJ, Ponsioen CI, Ubbink DT, D'Haens GR, Bemelman WA. The effect of appendectomy on the course of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14:545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Radford‐Smith GL, Edwards JE, Purdie DM et al Protective role of appendicectomy on onset and severity of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut 2002; 51:808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kronman MP, Zaoutis TE, Haynes K, Feng R, Coffin SE. Antibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: a population‐based cohort study. Pediatrics 2012; 130:e794–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sahami S, Kooij IA, Meijer SL, Van den Brink GR, Buskens CJ, Te Velde AA. The link between the appendix and ulcerative colitis: clinical relevance and potential immunological mechanisms. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111:163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brimnes J, Allez M, Dotan I, Shao L, Nakazawa A, Mayer L. Defects in CD8+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol 2005; 174:5814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yu QT, Saruta M, Avanesyan A, Fleshner PR, Banham AH, Papadakis KA. Expression and functional characterization of FOXP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13:191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Campieri M, Gionchetti P. Probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: new insight to pathogenesis or a possible therapeutic alternative? Gastroenterology 1999; 116:1246–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Farkas SA, Hornung M, Sattler C et al Preferential migration of CD62L cells into the appendix in mice with experimental chronic colitis. Eur Surg Res 2005; 37:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Chiba C, Bhan AK. Role of appendix in the development of inflammatory bowel disease in TCR‐alpha mutant mice. J Exp Med 1996; 184:707–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krieglstein CF, Cerwinka WH, Laroux FS et al Role of appendix and spleen in experimental colitis. J Surg Res 2001; 101:166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Petersson J, Schreiber O, Hansson GC et al Importance and regulation of the colonic mucus barrier in a mouse model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011; 300:G327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ 2013; 346:f432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dharmani P, Srivastava V, Kissoon‐Singh V, Chadee K. Role of intestinal mucins in innate host defense mechanisms against pathogens. J Innate Immun 2009; 1:123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nagalingam NA, Lynch SV. Role of the microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18:968–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ohkusa T, Sato N, Ogihara T, Morita K, Ogawa M, Okayasu I. Fusobacterium varium localized in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis stimulates species‐specific antibody. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17:849–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Intestinal bacteria and ulcerative colitis. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol 2003; 4:9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Linskens RK, Huijsdens XW, Savelkoul PH, Vandenbroucke‐Grauls CM, Meuwissen SG. The bacterial flora in inflammatory bowel disease: current insights in pathogenesis and the influence of antibiotics and probiotics. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 2001; 234:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H et al Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nature Genetics 2015; 47:979–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sun L, Nava GM, Stappenbeck TS. Host genetic susceptibility, dysbiosis, and viral triggers in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2011; 27:321–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Leong RW, Mitrev N, Ko Y. Hygiene hypothesis: is the evidence the same all over the world? Dig Dis 2016; 34:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 160:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bernstein CN. Epidemiologic clues to inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2010; 12:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Castiglione F, Diaferia M, Morace F et al Risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases according to the ‘hygiene hypothesis’: a case–control, multi‐centre, prospective study in Southern Italy. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6:324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hviid A, Svanstrom H, Frisch M. Antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhood. Gut 2011; 60:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]