Abstract

Purpose

Huntington disease (HD) is an incurable terminal disease. Thus, end of life (EOL) concerns are common in these individuals. A quantitative measure of EOL concerns in HD would enable a better understanding of how these concerns impact health-related quality of life. Therefore, we developed new measures of EOL for use in HD.

Methods

An EOL item pool of 45 items was field tested in 507 individuals with prodromal or manifest HD. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA, respectively) were conducted to establish unidimensional item pools. Item response theory (IRT) and differential item functioning analyses were applied to the identified unidimensional item pools to select the final items.

Results

EFA and CFA supported two separate unidimensional sets of items: Concern with Death and Dying (16 items), and Meaning and Purpose (14 items). IRT and DIF supported the retention of 12 Concern with Death and Dying items and 4 Meaning and Purpose items. IRT data supported the development of both a computer adaptive test (CAT) and a 6-item, static short-form for Concern with Death and Dying.

Conclusions

The HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying CAT and corresponding 6-item short form, and the 4-item calibrated HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose Scale demonstrate excellent psychometric properties. These new measures have the potential to provide clinically meaningful information about end of life preferences and concerns to clinicians and researchers working with individuals with HD. In addition, these measures may also be relevant and useful for other terminal conditions.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Neuro-QoL, PROMIS, HDQLIFE, Huntington disease, end of life, patient reported outcome (PRO)

Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease that causes motor, behavioral, and cognitive impairments; symptoms typically begin in midlife and progress to death within 20 years [1; 2]. End of life concerns may begin when patients become aware of their at-risk status, and are magnified after predictive testing reveals a gene mutation positive status, or after a clinical diagnosis of HD [3]. Experiences with the progression of disease and death in other family members [4] impacts the perspectives of at-risk and affected individuals about their own end of life (EOL) [4] as well as health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [3]. Individuals at-risk for HD, as well as those individuals across the full range of the HD disease spectrum (including those with no symptoms to those in the later stages of the disease), have identified EOL concerns as an important component of HRQOL [3]. Specifically, qualitative research in individuals with HD has identified the importance of EOL planning (including family planning, financial planning, and planning for palliative care) and concerns about how EOL affects the entire family (both in watching other family members suffer and die from this disease, as well as concerns about the burden that their disease may place on other family members) as important components of HRQOL [3]. A quantitative measure of EOL concerns in HD would facilitate our understanding of their relevance to HRQOL, and of their sensitivity to treatments or interventions [5-9]. An ideal HD-specific EOL measure should be appropriate for patients at all stages of the disease process, from the pre-symptomatic or prodromal period, to the late stages when cognitive decline may impact comprehension and judgment about EOL issues [10]. Such a tool could, in turn, assist health care providers in initiating discussions about EOL decision-making, help them to determine at what point patients would be most receptive to EOL discussions, [11] and increase their understanding about how EOL beliefs change over the disease course [12].

Several measures exist which were originally intended to measure HRQOL, but these measures were either developed for use in other diseases such as cancer, (e.g., revised Hospice Quality of Life Index [13]; Death and Dying Distress Scale [14; 15]; McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire [16; 17]; QUAL-EC [18]) or are overly generic (e.g., CANHELP Lite [19]; EOL-PRO [20]; the Missoula-VITAS quality of life index [21]; Palliative Patients’ Dignity Scale [22]; Patient Needs Assessment in Palliative Care [23]; Valuation of Life [24]; QUAL-E [25]). These tools do not capture EOL concerns specific to HD (e.g., concerns related to watching other family members suffer from and die from the disease; concerns about the burden of having HD places on other family members; concerns about your children inheriting the disease from you; the fact that there is a gene test that can accurately predict who will get symptoms, but not when), take too long to implement (i.e., the CANHELP [26]), and/or include substandard psychometric properties [6-8]. In addition, all of these measures neglect to address concerns about EOL impact on HRQOL during the earlier stages of a neurodegenerative disease.

To address these shortcomings, this study focused on developing new measures that could capture the EOL concerns reported by individuals with HD, their caregivers, and clinical providers [3]. Specifically, we used state-of-the-science psychometric methods to create calibrated item banks that are comprised of numerous items that allow for administration as either a computerized adaptive test (CAT) or as a static short form; administration options that provide accurate measurement with low response burden [27]. Below, we highlight the development of two new measures of EOL concerns, which are part of a new measurement system, the HDQLIFE [28].

Methods

Individuals with prodromal or manifest HD were invited to participate in this study. Participants were at least 18 years old, able to read and understand English, and had either a positive test for the CAG expansion for HD (HD is a caused by an expansion of CAG repeats in the HD gene [HTT]) and/or a clinical diagnosis of HD, and had the ability to provide informed consent. In cases where there were concerns about the cognitive capacity of a potential participant, the Orientation Log – HD (O-Log-HD) was administered. The O-Log-HD was adapted from the Orientation Log (O-Log) [29] and provides an assessment of mental status; possible scores range from 0-30 and participants with scores < 25 were not eligible to participate in the study. Participants were recruited from several specialized HD treatment centers (the University of Michigan, the University of Iowa, the University of California-Los Angeles, Indiana University, Johns Hopkins University, Rutgers University, Struthers Parkinson's Center, and Washington University), through electronic medical records [30], the National Research Roster for Huntington's Disease, and articles/advertisements in HD-specific newsletters and websites. Additionally, the majority of the prodromal HD participants in this study were recruited through the Predict-HD study [31-33], a longitudinal prospective study (over 30 sites worldwide), examining the clinical markers of prediagnostic (i.e., prodromal) HD; this cohort includes over 700, well-characterized individuals with prodromal HD.

HDQLIFE End of Life Item Pool

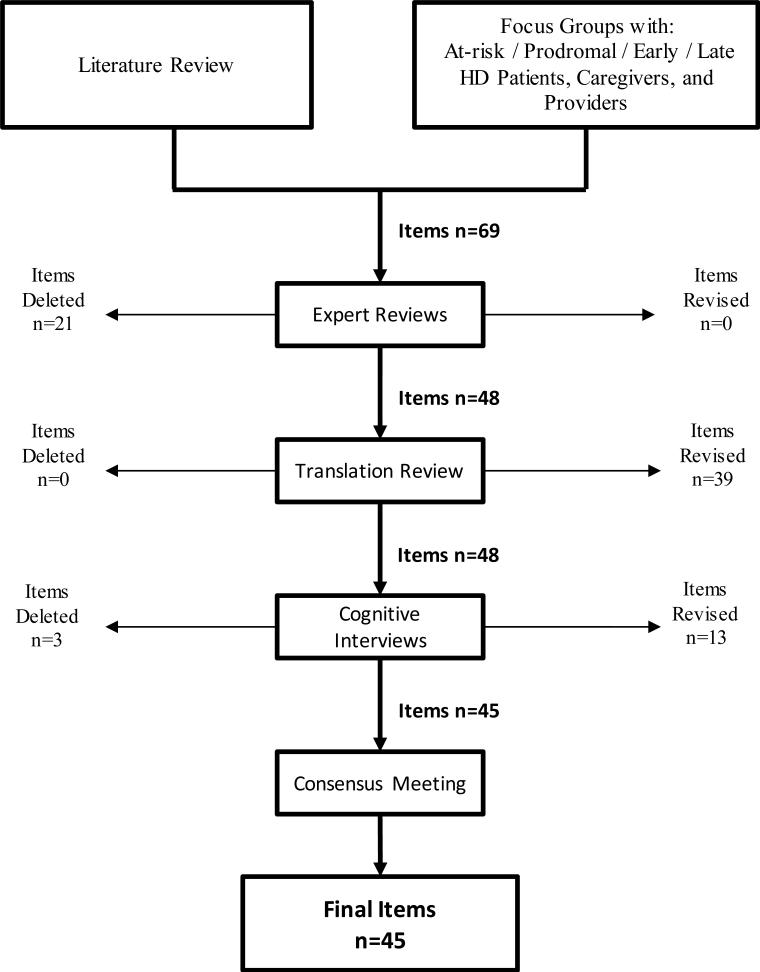

Sixty-nine items that examined concerns with EOL were developed through an iterative process [28]. Item content was derived in conjunction with the Neuro-QoL project [34], and was comprised of literature reviews [34; 35], as well as focus group data in HD, and expert input [3]. Items were refined through expert review, translatability review, and cognitive interviews with individuals with HD following established methodology [36]; Figure 1 documents this iterative process. The final item pool was comprised of 45 items.

Figure 1.

Procedures to develop the new end of life concerns item pool

Participant Characterization

The Total Functional Capacity (TFC) scale [37] from the United Huntington's Disease Rating Scales (UHDRS) [38] was administered to all participants. The TFC is a clinician administered 5-item scale designed to evaluate day-to-day functioning across the domains of occupation, finances, domestic chores, activities of daily living, and care level. Scores range from 0 to 13 with higher scores indicating better functioning. Participants with an HD diagnosis were classified as either early-stage (TFC sum scores of 7-13; Stages 1 and 2) or later-stage HD (TFC sum scores of 0-6; Stages 3-5).

Analysis Approach

Unidimensionality

Factor analyses were used to establish the unidimensionality of the item pool. First, our sample was randomly divided into two data sets. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a PROMAX rotation was used to determine number of factors within the item pool according to Eigenvalues (> 1) and the number of factors before the break in the scree plot. Item loadings were used to determine items and their associated factor (criterion > 0.4). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for robust weighted least square estimation for ordinal data was then conducted to confirm the factor structure determined based on the EFA results [39; 40]. Good fit was established as a comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.1 [41-44], and residual correlations < .15 (i.e., maintain local independence) [45-47]; fit indices meet established standards for CFA when it is applied to PRO development [47]. In addition, Cronbach's alpha was examined to determine acceptable reliability of the measure (i.e., > .80). EFA and CFA analyses were conducted using MPLUS 6.11 [48].

Item Response Theory (IRT) Anlayses

The finalized item pools were then calibrated using Samejima's graded response model (GRM) [49]; these analyses were conducted in IRTPRO 2.1 [50]. This analysis estimated item threshold and item slope parameters, which were then used to calculate information functions at the level of individual items and at the level of the entire item bank, to characterize measurement precision on the measurement continuum at both item and scale levels. Differential item functioning (DIF) was used to evaluate stability of measurement properties for each individual item between sub-groups by using IRT scaled-score based ordinal logistic regression [51]. DIF analyses were conducted using the LORDIF package within R (Version 0.3-2) [52]. DIF was evaluated on gender, age (≤ 40 vs. >40 years; ≤50 vs. >50 years), and education (high school graduate or less vs. > high school). Items with DIF (non-negligible DIF criterion: R2 > 0.02 and p<.01) were discussed by the study team and were candidates for exclusion. Firestar CAT simulation software [53] was used to conduct simulation analyses to: 1) determine the number of items administered by the CAT for different ability levels for the trait; and 2) examine the relationship between the simulated CAT score and scores derived using all items in the bank.

Other Demographic Comparisons

We collected demographic information on age, gender, education, and race. Pearson correlations between the new HDQLIFE measures and demographic variables (i.e., age and education) were examined. In addition, an independent sample t test was conducted to determine if there were significant gender differences for these HDQLIFE measures.

Sample Size Considerations

Study sample size was determined based on sample size requirements for IRT, DIF, EFA and CFA analyses. When using Graded Response Models (GRM), larger sample sizes produce more stable parameter estimation [49; 54]. In general, established standards suggest that a minimum of 5-10 individuals are needed for every item within an item pool in order to establish stable parameter estimates [55-57]; thus 500 individuals were needed for reliable item response theory (IRT) calibration data. Established standards for differential item functioning (DIF) analyses (an indication of item bias) suggest that at least 200 participants are needed within each condition; considering these parameters, sampling stratification targeted age (< 40 vs. ≥ 40 and <50 vs. ≥ 50), gender (male vs. female), and education (< high school vs. ≥ high school]) [58]. Finally, EFA and CFA analyses recommend the inclusion of ~5 people per item analyzed [55; 57]; thus 250 individuals were needed for EFA and CFA analyses, respectively (5 individuals for ~50 items per item pool).

Results

Five hundred seven (507) individuals with prodromal or manifest HD participated in this study. Participants were sampled to represent the entire continuum of HD symptomatology; 196 individuals had prodromal HD (CAG > 35, but did not yet have an HD clinical diagnosis), 193 had early-stage HD (sum scores of 7-13 on the TFC), 117 had later-stage HD (sum scores of 0-6 on the TFC), and 1 participant was not classifiable. Participants ranged in age from 18-81 years (M = 49.01, SD = 13.21) and 40.8% of participants were male. Significant differences were seen for age (as symptoms are progressive with age), F (2, 503) = 47.360, p< .0001, with individuals who were prodromal (M = 42.60, SD = 12.04) being significantly younger than the early-HD group (M = 51.91, SD = 12.41) and the late-HD group (M = 55.07, SD = 11.89). The early-HD group was also significantly younger than the late-HD group. Groups did not differ on gender, Χ2 (2, N = 506) = 3.193, p = .20. The majority of participants were Caucasian (96.4%); 2.0% were African American, 1.4% were classified as “other,” and 0.2% were unknown. Participants’ education ranged from 4 to 26 years (M = 15.06, SD = 2.88). While there were group differences in education, F (2, 501) = 14.781, p< .0001, these differences were small; early- (M = 14.74, SD = 2.78) and late-HD (M = 14.22, SD = 2.62) had 1 to 1.5 years less education relative to the prodromal HD group (M = 15.88 years, SD = 2.94).

Unidimensionality

Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA)

Findings based on a random sample of 254 individuals indicated that the data could largely be explained by 4 factors (Table 1); the first factor included 14 items that generally represented meaning and purpose; the second factor included only two highly-similar items concerning family members who had died of HD; the third factor included 12 items that generally represented anxieties and worries concerning death; the fourth factor included 16 items that generally represented thoughts concerning death and dying; and finally, 1 item did not load on any of the four factors. Because of the spurious nature of the second factor, and the fact that there is an existing PROMIS measure concerning anxiety, we elected to focus on developing measures that reflected meaning and purpose (factor 1) and death and dying (factor 4). For the remainder of analyses, we focused solely on these two factors.

Table 1.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results for the HDQLIFE End of Life Concerns Item Pool

| End of Life Concerns Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I live my life to the fullest.a | 0.87 | 0.16 | −0.19 | 0.22 |

| I am making the most out of the time I have left.a | 0.83 | 0.22 | −0.18 | 0.14 |

| I am satisfied with my ability to make the most out of the time that I have left.a | 0.82 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.19 |

| I am satisfied with my control over my medical care.a | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.14 |

| I am satisfied with my decisions about my healthcare.a | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.20 | −0.10 |

| I am at peace with the fact that I will die.a | 0.68 | −0.31 | 0.30 | −0.12 |

| My life has meaning.a | 0.68 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.31 |

| I am at peace with death.a | 0.65 | −0.39 | 0.30 | −0.16 |

| I find meaning in my illness.a | 0.63 | −0.14 | 0.15 | −0.08 |

| I feel comfortable talking about my death.a | 0.63 | −0.22 | 0.23 | −0.23 |

| My illness strengthens my faith (spiritual beliefs, religion).a | 0.58 | −0.10 | −0.01 | −0.11 |

| End of life planning is important.a | 0.57 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.05 |

| There are important things that I still want to do with my life.a | 0.55 | 0.03 | −0.35 | 0.31 |

| Matters regarding my estate are in order.a | 0.53 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.14 |

| I think about my family members who died from the disease.b | 0.04 | 0.76 | 0.50 | −0.01 |

| How often did you think about your family members that have died from this disease?b | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| I am concerned with how my death will impact my family.a | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.99 | −0.16 |

| I am worried about how my family will deal with my death.a | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.96 | −0.06 |

| I am worried about how my family will cope with my death.a | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.96 | −0.11 |

| I worry about the burden that my disease places on my family and friends.a | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.03 |

| Seeing other people with my illness scares me.a | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.67 | 0.15 |

| I am concerned about leaving some things unfinished.a | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.11 |

| Seeing other people with my illness makes me think about my own death.a | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.16 |

| I feel like a financial burden to my family.a | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.25 |

| I am afraid of what the future holds for me.a | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.54 | 0.29 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you worry about the emotional burden that your disease places on your family or friends?b | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.37 |

| I am afraid of suffering.a | 0.14 | −0.18 | 0.51 | 0.19 |

| I worry about my children inheriting this disease.a | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.46 | −0.03 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you worry about how your family would cope with your death?b | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you feel like a financial burden to your family?b | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.46 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about dying?b | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.97 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you preoccupied with thoughts of dying?b | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.94 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about your own death?b | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.90 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you preoccupied with thoughts of death?b | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.90 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you feel anxiety that you would die?b | 0.00 | −0.31 | 0.14 | 0.80 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you talk to others about your own death?b | −0.14 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.74 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about ending your life?b | 0.25 | 0.20 | −0.21 | 0.74 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you become sad when you thought about the end of your life?b | −0.03 | −0.21 | 0.16 | 0.72 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you worried your illness would get worse?b | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you afraid of dying?b | 0.02 | −0.39 | 0.19 | 0.64 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you afraid of the future?b | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.25 | 0.63 |

| I think about how I will die.b | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.58 |

| In the past 7 days to what degree did you have to push yourself to keep going?a | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.45 |

| I feel in control of my life.b | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| I am concerned that I won't be able to have children.a | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

Note.

response options = not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much

response options = never, rarely, sometimes, often, always.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Using the second random sample of 253 individuals, CFAs were conducted separately on each of the two subdomains (i.e., meaning and purpose and death and dying) to confirm unidimensionality.

Meaning and Purpose

Content considerations and large residual correlations caused us to reduce the number of items for this scale to 7 from 14 items. Results indicated that all 7 items examining meaning and purpose generally fit the data well; CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.11, all r2 > .03. Additionally, all residual correlations were ≤ 0.11 and all item-total correlations were > 0.4. Cronbach's alpha for this measure was 0.84.

Death and Dying

Examination of all 16 items examining difficulties with death and dying revealed 3 items with large residual correlations. These items were deleted resulting in 13 final items; all residual correlations were ≤ 0.15 for these items. These 13 items were then examined using a 1 factor CFA; the analysis for these 13 items yielded a CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.15, all r2 > .03. All item-total correlations were > 0.4. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.94.

IRT Analyses

Meaning and Purpose

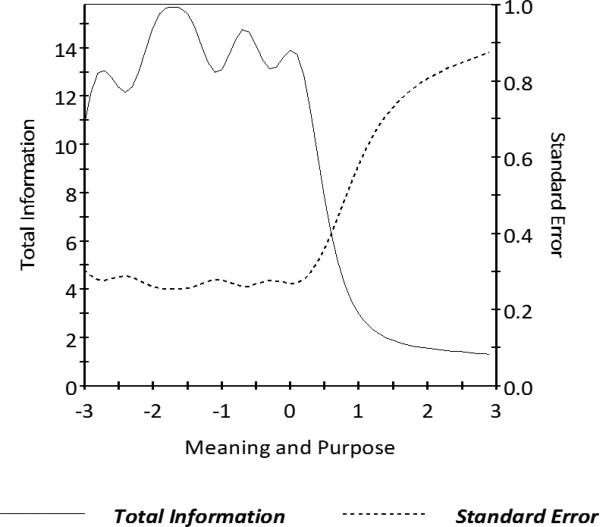

The seven selected items were analyzed using graded response model (GRM) [54], in accordance with PROMIS recommendations [50]. IRT parameter estimates indicated slopes ranging from 0.84 to 4.75 and thresholds ranging from −3.26 to 1.78 (See Table 2). S-X2 model fit statistics were examined using IRTPRO; although 5 items had misfit statistics (p < 0.05) they were included for further consideration. Information was good (i.e., marginal reliability = 0.83), for scale scores between −3 and 0.5 (see Figure 2 for the scale information function). No items showed DIF on age, gender, or education. Items with slopes < 2.0, as well as misfit statistics, were omitted from the final item set (“I feel comfortable talking about my death;” “I find meaning in my illness;” and “There are important things that I still want to do with my life”). Thus, 4-items were retained for inclusion in this scale and a static short form (instead of a computer adaptive test) was developed.

Table 2.

HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose Item Parameters

| Item | Slope | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel comfortable talking about my death. | 0.84 | −2.72 | −1.60 | −0.10 | 1.21 |

| I am making the most out of the time I have left. | 2.64 | −2.26 | −1.68 | −0.83 | −0.01 |

| My life has meaning. | 2.26 | −2.78 | −2.13 | −1.11 | −0.26 |

| I find meaning in my illness. | 0.91 | −1.27 | −0.64 | 0.69 | 1.78 |

| There are important things that I still want to do with my life. | 1.30 | −3.26 | −2.44 | −1.28 | −0.34 |

| I am satisfied with my ability to make the most out of the time that I have left. | 3.66 | −1.87 | −1.40 | −0.71 | 0.01 |

| I live my life to the fullest. | 4.75 | −1.91 | −1.48 | −0.65 | 0.11 |

Note. Items that are bolded were selected for inclusion in the final, 4-item short form

Figure 2. HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose Test Information.

In general, we want total information to be > 9.0 and standard error to be < 0.33 (this provides a reliability of 0.9). This figure shows excellent total information and standard error for Meaning and Purpose scale scores between −3 and 0.5.

Concern with Death and Dying

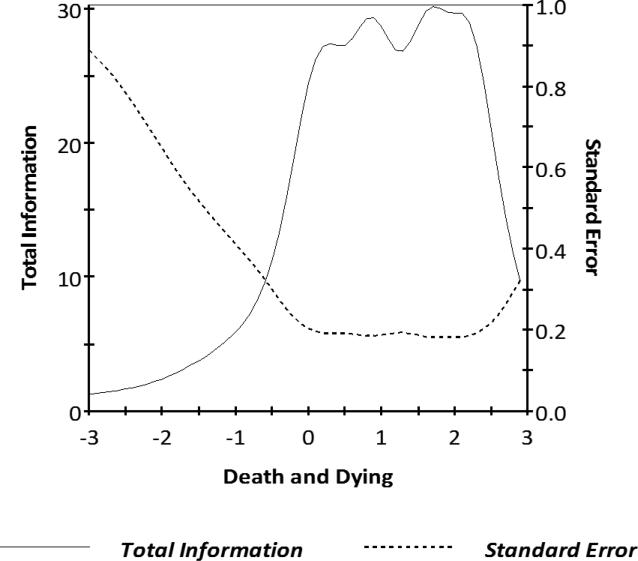

One item, “I feel in control of my life” was deleted due to a poor slope (0.98). The remaining 12 items indicated slope parameters ranging from 1.48 to 4.57 and threshold parameters ranging from −0.98 to 3.65 (Table 3). Information was good (i.e., reliability ≥ .80), for scale scores between −1.5 and 3.0 (see Figure 3 for the scale information function). Although S-X2 indicated that 5 of the 12 items had misfit (p < 0.05); these items were retained for further consideration. Marginal reliability was 0.91. DIF was not found for age (<50 vs. ≥50 or <40 vs. ≥40), gender (male vs. female), or education (some college and lower vs. college degree and higher). A 6-item calibrated Concern with Death and Dying short form was then created based on information of slope parameters, item characteristic curves, item information, and average item difficulty, as well as input from HD and measurement development experts on clinical characteristics (e.g., items were selected that represent different important clinical components of concerns with death and dying). Specifically, we balanced the psychometric considerations with clinical content to ensure representativeness of the items that were selected for the short form.

Table 3.

HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying Item Parameters

| Concern with Death and Dying Item | Slope | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about ending your life? | 1.48 | 1.28 | 2.02 | 2.73 | 3.38 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you become sad when you thought about the end of your life? | 2.21 | −0.07 | 0.59 | 1.52 | 2.12 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you preoccupied with thoughts of dying? | 4.55 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 2.18 |

| In the past 7 day how often did you feel anxiety that you would die? | 2.50 | 0.17 | 0.87 | 1.70 | 2.24 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about dying? | 4.57 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 1.60 | 2.23 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you think about your own death? | 4.57 | −0.02 | 0.80 | 1.61 | 2.18 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you talk to others about your own death? | 1.62 | 0.28 | 1.27 | 2.57 | 3.65 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you worried your illness would get worse? | 1.77 | −0.98 | −0.19 | 0.83 | 1.57 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you preoccupied with thoughts of death? | 3.64 | 0.37 | 1.02 | 1.81 | 2.41 |

| In the past 7 days how often did you worry about how your family would cope with your death? | 1.59 | −0.65 | 0.12 | 1.07 | 1.73 |

| In the past 7 days how often were you afraid of the future? | 1.82 | −0.61 | 0.12 | 1.20 | 2.13 |

| I think about how I will die. | 1.98 | −0.90 | 0.20 | 1.56 | 2.21 |

Note. Items that are bolded were selected for inclusion on the 6-item short form.

Figure 3. HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying Test Information.

This figure shows the test information and scale score standard error for different scale scores in standard deviation units for the Concern with Death and Dying scale. Information was good (i.e., reliability ≥ .80), for scale scores between −1.5 and 3.0.

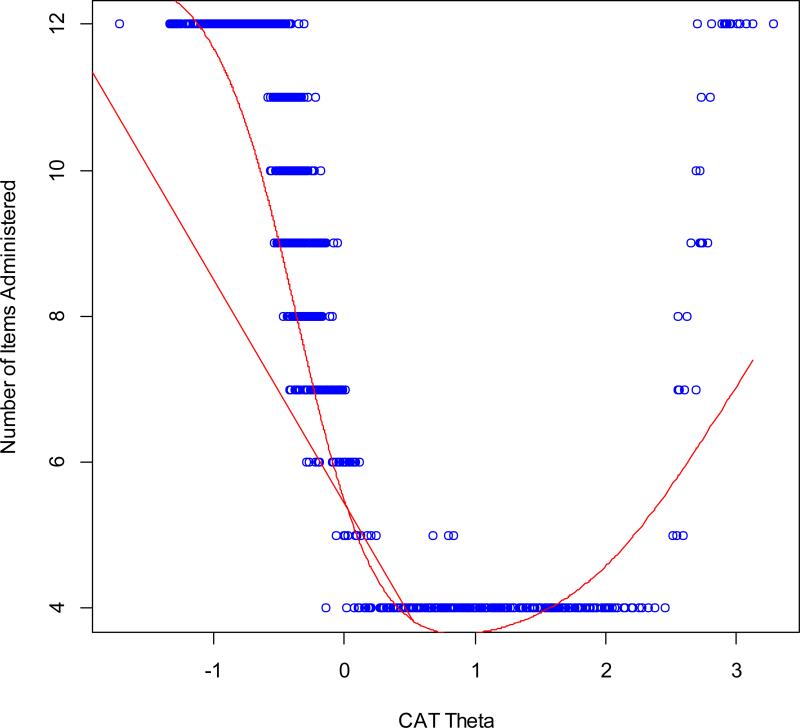

Simulation results showed that the average number of items administered to 10,000 virtual respondents by the Firestar CAT simulation software was 7.02. The correlation between the CAT scores and the full item-bank was 0.99, indicating that the CAT based on the Concern with Death and Dying item bank can produce results that are very similar to those obtained with administration of the entire 12-item set. Figure 4 shows the number of CAT items used for different scale scores in standard deviation units: at −1 SD units, the CAT always used all 12 items in the item bank; at +1 and +2 SD units, the CAT always used the minimum number of 4 items in the item bank; and at 3 SD units the CAT used all 12 items in the item bank. Thus, the CAT simulation indicates that fewer items were needed to estimate scores for individuals with greater concern with death and dying than for individuals with less concern with death and dying.

Figure 4. HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying Number of CAT Items by CAT Theta.

This figure shows the number of CAT items used for different scale scores in standard deviation units: at −1 SD units, the CAT always used all 12 items in the item bank; at +1 and +2 SD units, the CAT always used the minimum number of 4 items in the item bank; and at 3 SD units the CAT used all 12 items in the item bank.

Scoring of Short Forms

The IRT-scaled scores (theta) were converted into a standardized score utilizing a t score (mean = 50, SD = 10; referenced to the HD population represented by the current sample); see Table 4 and 5 for a summed score scale conversion table for the short forms for Meaning and Purpose, and Concern with Death and Dying, respectively. Higher scores indicate more of the construct (i.e., higher scores for Meaning and Purpose indicate greater meaning and purpose in ones’ life, whereas higher scores on Concern with Death and Dying, indicate greater concerns or preoccupation with death and dying).

Table 4.

HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose SF Summed Score to t Score Conversion Table

| Meaning and Purpose SF Summed Score | Meaning and Purpose t Score |

|---|---|

| 4 | 22 |

| 5 | 25 |

| 6 | 27 |

| 7 | 29 |

| 8 | 31 |

| 9 | 33 |

| 10 | 35 |

| 11 | 37 |

| 12 | 39 |

| 13 | 40 |

| 14 | 42 |

| 15 | 44 |

| 16 | 46 |

| 17 | 48 |

| 18 | 51 |

| 19 | 54 |

| 20 | 61 |

Note. SF = 4-item Short Form

Table 5.

HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying SF t Score Conversion Table

| Death and Dying SF Summed Score | Death and Dying t Score |

|---|---|

| 6 | 36 |

| 7 | 41 |

| 8 | 44 |

| 9 | 46 |

| 10 | 48 |

| 11 | 51 |

| 12 | 52 |

| 13 | 54 |

| 14 | 56 |

| 15 | 57 |

| 16 | 59 |

| 17 | 60 |

| 18 | 61 |

| 19 | 63 |

| 20 | 64 |

| 21 | 65 |

| 22 | 67 |

| 23 | 68 |

| 24 | 70 |

| 25 | 71 |

| 26 | 73 |

| 27 | 74 |

| 28 | 76 |

| 29 | 77 |

| 30 | 80 |

Note. SF = 6-item Short Form

Other Demographic Comparisons

There was a small, but significant negative relationship between age and HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying (r = −.12, p = .009); there was no relationship between age and HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose (r = .05, p = .24). Relationships between education and HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying (r = .01, p = .76), and education and HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose (r = −.07, p = .10) were negligible. Independent samples t test indicated that women (M = 50.92; SD = 9.39) report more Concern with Death and Dying than men (M = 48.80; SD =8.24), t(493) = −2.59, p = .01; there were no differences between men (M=49.46; SD = 9.28) and women (50.42; SD 8.97) for Meaning and Purpose, t(493) = −1.16, p = .25.

Discussion

This paper presents the development of two new patient reported outcomes measures from HDQLIFE [28] that evaluate end of life concerns in HD: Meaning and Purpose, and Concern with Death and Dying. Analyses supported the development of a 4-item calibrated scale to capture Meaning and Purpose, and an item bank that can be administered as either a CAT or a 6-item short form to capture Concern with Death and Dying. These are the first measures of EOL that have been developed specifically for use in HD and include the first CAT for use in evaluating patient reported outcomes regarding EOL concerns. CAT allows for a much briefer approach towards assessment, in that only the most relevant items are administered; item selection is based on the participants’ previous response. Furthermore, these measures are scored using a t metric, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10; higher scores indicate more of the construct (i.e., higher scores for Meaning and Purpose indicate greater meaning and purpose in ones’ life, whereas higher scores on Concern with Death and Dying indicate greater concerns or preoccupation with death and dying). This approach allows for an estimation of an individual's functioning relevant to the reference group (in this case, other individuals with HD). For example, scores of 60 or greater on Concern with Death and Dying indicate that the individual is more preoccupied with these thoughts than 68.27% of people with HD. Scores above 70 indicate thoughts/preoccupation with death and dying that exceed 95.45% of individuals with HD. Given the fact that talking about these issues can be uncomfortable for both the patient and the provider [59], that individuals with HD often do not discuss these concerns with physicians [60], that physicians often neglect to initiate discussions about EOL options with patients [61; 62], and that this has been recognized as a priority area for HD clinical care [10; 60; 61; 63], these measures may serve as a catalyst to help initiate these difficult conversations between patients and providers. Furthermore, scores on these measures may potentially serve as referents for making appropriate clinical referrals for palliative care services and to identify distressed individuals who might benefit from consultation with mental health services and/or pastoral counselors.

There is no cure for HD; thus, all HD care is essentially palliative. There are many evidence-based palliative care interventions available to increase HRQOL of persons with HD [4-7]. However, denial, stigma, and conflicting family perceptions of what constitutes quality of life and a “good death” are barriers to engaging in EOL discussions [64]. HD has some unique characteristics that make disease-specific EOL measures critical. Since HD is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder (i.e., it runs in families), persons with a positive gene test have often witnessed the decline and death of several family members while they contemplate their own genetic fate. In addition, people with the HD gene mutation generally have normal functioning until mid-life when subtle symptoms begin, and then slowly progress to increasing levels of impairment over 15-20 years or more. Our measures are designed to evaluate EOL across the entire disease course. This will enable us to better understand how beliefs about EOL change over time in people with HD, and how they are impacted by their inevitable cognitive decline. Furthermore, the EOL measures developed here are suitable for use in later-stage patients, and will help care providers to evaluate the needs/wants of these individuals in order to provide a supportive environment during the end of life stage of HD. Current healthcare policies do not provide support for long-term palliative care [4]. There is also evidence that patients with neurological conditions are less likely than other types of patients, such as patients with cancer, to make advanced directives or receive palliative care at the end of life [65]. Our HD-specific EOL measures can help identify patients who could benefit from palliative care and advance directives decision making, as well as identify when patients are likely to be most receptive to these interventions.

While this study has a number of strengths, there are also some limitations. Our study sample might not be representative of all people with HD. We recruited participants from specialized HD clinical centers and from the PREDICT-HD study. Most persons with HD do not have access to specialized HD centers. Participants in the PREDICT-HD study are persons who have independently chosen to be tested for the HD gene mutation prior to symptom onset [31-33]. It is estimated that less than 25% of persons at risk for HD undergo pre-symptomatic genetic testing [66]. Thus, our sample might be more open to discussing EOL concerns because they have given consideration to their own futures through seeking HD genetic testing. Previous research in HD has indicated that persons with HD may demonstrate impaired awareness of their illness state [67]. This could potentially lead to them reporting fewer concerns with death and dying as the disease progresses, which would be counterintuitive. Thus, including caregiver perspectives in HD studies is important; a factor that is not represented by our study design (which focused solely on patient-centered outcomes). Future studies, especially those examining individuals in the later stages of the disease, should consider including caregivers. Finally, some study participants completed the assessments via computers at home and might have received input and assistance from others while others completed the assessments in a research setting. Future work should consider examining group differences among these responders.

Taken together, these are the first HD-specific measures that have been developed to capture EOL issues such as meaning of life and concerns about death and dying over the course of HD. In addition, although these measures were developed for use in HD research, they may also have utility in the HD clinic, and might be applicable to other conditions that share similar characteristics, such as early-onset Alzheimer disease (which shares an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and a progressive course), as well as other common neurological diseases that involve behavioral, cognitive, and/or motor symptoms (e.g. Parkinson disease, Multiple Sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease). Future efforts should focus on validating these new measures in other terminal conditions.

Acknowledgements

Work on this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS077946) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000433). In addition, a portion of this study sample was collected in conjunction with the Predict-HD study. The Predict-HD was supported by the NIH, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS040068), the NIH, Center for Inherited Disease Research (provided supported for sample phenotyping), and the CHDI Foundation (award to the University of Iowa). We thank the University of Iowa, the Investigators and Coordinators of this study, the study participants, the National Research Roster for Huntington Disease Patients and Families, the Huntington Study Group, and the Huntington's Disease Society of America. We acknowledge the assistance of Jeffrey D. Long, Hans J. Johnson, Jeremy H. Bockholt, Roland Zschiegner, and Jane S. Paulsen. We also acknowledge Roger Albin, Kelvin Chou, and Henry Paulsen for the assistance with participant recruitment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

Carlozzi, N.E. currently has research grants from the NIH; she is also supported by grant funding from the NIH, NIDILRR, and CHDI; she declares no conflicts of interest.

Downing, N.R. declares no conflicts of interest.

McCormack, M.K. currently has grants from the NJ Department of Health; he declare no conflicts of interest.

Schilling, S.G. has a research grant from NSF. He also is supported by grant funding from NIH. He declares no conflicts of interest.

Perlmutter, J.S. currently has funding from the NIH, HDSA, CHDI, and APDA. He has received honoraria from the University of Rochester, American Academy of Neurology, Movement Disorders Society, Toronto Western Hospital, St Lukes Hospital in St Louis, Emory U, Penn State, Alberta innovates, Indiana Neurological Society, Parkinson Disease Foundation, Columbia University, St. Louis University, Harvard University and the University of Michigan.

Hahn, E.A. currently has research grants from the NIH; she is also supported by grant funding from the NIH and PCORI, and by research contracts from Merck and EMMES; she declares no conflicts of interest.

Lai J.-S. currently has research grants from the NIH; she declares no conflicts of interest.

Frank, S. receives salary support from the Huntington Study Group for a study sponsored by Auspex Pharmaceuticals. There is no conflict of interest.

Quaid, K.A. has research funding from NIH, NIA, NCRR, NINDS and CHDI. She also has funding from HDSA. She has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Paulsen, J.S. currently has research grants from the NIH; she is also supported by grant funding from NIH, NINDS, and CHDI; she declares no conflicts of interest.

Cella, D. receives grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and reports that he has no conflicts of interest.

Goodnight, S.M. is supported by grant funding from the NIH and the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation; she declares no conflicts of interest.

Miner, J.A. is supported by research grants from the NIH; she declares no conflict of interest.

Nance, M.A. declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

HDQLIFE Site Investigators and Coordinators: Noelle Carlozzi, Praveen Dayalu, Stephen Schilling, Amy Austin, Matthew Canter, Siera Goodnight, Jennifer Miner, Nicholas Migliore (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Jane Paulsen, Nancy Downing, Isabella DeSoriano, Courtney Shadrick, Amanda Miller (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA); Kimberly Quaid, Melissa Wesson (Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN); Christopher Ross, Gregory Churchill, Mary Jane Ong (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); Susan Perlman, Brian Clemente, Aaron Fisher, Gloria, Obialisi, Michael Rosco (University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Michael McCormack, Humberto Marin, Allison Dicke (Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ); Joel Perlmutter, Stacey Barton, Shineeka Smith (Washington University, St. Louis, MO); Martha Nance, Pat Ede (Struthers Parkinson's Center); Stephen Rao, Anwar Ahmed, Michael Lengen, Lyla Mourany, Christine Reece, (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH); Michael Geschwind, Joseph Winer (University of California – San Francisco, San Francisco, CA), David Cella, Richard Gershon, Elizabeth Hahn, Jin-Shei Lai (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL).

References

- 1.Ross CA, Margolis RL, Rosenblatt A, Ranen NG, Becher MW, Aylward E. Huntington disease and the related disorder, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Medicine (Baltimore) 1997;76(5):305–338. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulsen JS. Early Detection of Huntington Disease. Future Neurol. 2010;5(1) doi: 10.2217/fnl.09.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlozzi NE, Tulsky DS. Identification of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) issues relevant to individuals with Huntington disease. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(2):212–225. doi: 10.1177/1359105312438109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, Marinus J, Roos RAC. Thinking about the end of life: a common issue for patients with Huntington's disease. Journal of Neurology. 2014;261(11):2184–2191. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno JM, Byock I, Field MJ. Research agenda for developing measures to examine quality of care and quality of life of patients diagnosed with life-limiting illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Tulsky JA. Evolution in measuring the quality of dying. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(3):407–414. doi: 10.1089/109662102320135298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson AM, Lynn J, Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Sun VC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Lorenz KA. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1848–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Soest-Poortvliet MC, van der Steen JT, Zimmerman S, Cohen LW, Reed D, Achterberg WP, Ribbe MW, de Vet HC. Selecting the best instruments to measure quality of end-of-life care and quality of dying in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers G, Echteld MA, de Vet HC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Linden MH, Deliens L. Content and spiritual items of quality-of-life instruments appropriate for use in palliative care: a review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klager J, Duckett A, Sandler S, Moskowitz C. Huntington's disease: a caring approach to the end of life. Care Manag J. 2008;9(2):75–81. doi: 10.1891/1521-0987.9.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huntington Society of Canada Factsheets for healthcare professionals: Palliative care for individuals in late-stage Huntington disease. 2010.

- 12.Downing NR, Williams JK, Paulsen JS. Couples' attributions for work function changes in prodromal Huntington disease. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(4):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMillan SC, Weitzner M. Quality of life in cancer patients: use of a revised Hospice Index. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(5):282–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause S, Rydall A, Hales S, Rodin G, Lo C. Initial validation of the Death and Dying Distress Scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(1):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo C, Hales S, Zimmermann C, Gagliese L, Rydall A, Rodin G. Measuring death-related anxiety in advanced cancer: preliminary psychometrics of the Death and Dying Distress Scale. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 2):S140–145. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230e1fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi- centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11(1):3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9(3):207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo C, Burman D, Swami N, Gagliese L, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. Validation of the QUAL-EC for assessing quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(4):554–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyland DK, Jiang X, Day AG, Cohen SR, Canadian Researchers at the End of Life, N. The development and validation of a shorter version of the Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project Questionnaire (CANHELP Lite): a novel tool to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(2):289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCaffrey N, Skuza P, Breaden K, Eckermann S, Hardy J, Oaten S, Briffa M, Currow D. Preliminary development and validation of a new end-of-life patient-reported outcome measure assessing the ability of patients to finalise their affairs at the end of life. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byock IR, Merriman MP. Measuring quality of life for patients with terminal illness: the Missoula-VITAS quality of life index. Palliat Med. 1998;12(4):231–244. doi: 10.1191/026921698670234618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudilla D, Oliver A, Galiana L, Barreto P. A new measure of home care patients' dignity at the end of life: The Palliative Patients' Dignity Scale (PPDS). Palliat Support Care. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buzgova R, Kozakova R, Sikorova L, Zelenikova R, Jarosova D. Development and psychometric evaluation of patient needs assessment in palliative care (PNAP) instrument. Palliat Support Care. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawton MP, Moss M, Hoffman C, Kleban MH, Ruckdeschel K, Winter L. Valuation of life: a concept and a scale. J Aging Health. 2001;13(1):3–31. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinhauser KE, Bosworth HB, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, Parker J, Tulsky JA. Initial assessment of a new instrument to measure quality of life at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(6):829–841. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Skrobik Y, Jiang X, Day AG, Cohen SR, Canadian Researchers at the End of Life, N. The development and validation of a novel questionnaire to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care: the Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project (CANHELP) Questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2010;24(7):682–695. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, Choi S. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(Suppl 1):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlozzi NE, Schilling SG, J.-S., L., Paulsen JS, Hahn EA, Perlmutter JS, Ross CA, Downing NR, Kratz AL, McCormack MK, Nance MA, Quaid KA, Stout J, Gershon RC, Ready R, Miner JA, Barton SK, Perlman SL, Rao SM, Frank S, Shoulson I, Marin H, Geschwind MD, Dayalu P, Foroud T, Goodnight SM, Cella D. HDQLIFE: Development and assessment of health-related quality of life in Huntington disease (HD). Quality of Life Research. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1386-3. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novack T. [March 3, 2015];The Orientation Log. 2000 from http://www.tbims.org/combi/olog.

- 30.Hanauer DA, Mei Q, Law J, Khanna R, Zheng K. Supporting information retrieval from electronic health records: A report of University of Michigan's nine-year experience in developing and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE). J Biomed Inform. 2015;55:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulsen JS, Hayden M, Stout JC, Langbehn DR, Aylward E, Ross CA, Guttman M, Nance M, Kieburtz K, Oakes D, Shoulson I, Kayson E, Johnson S, Penziner E. Preparing for preventive clinical trials: The predict-HD study. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63(6):883–890. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulsen JS, Langbehn DR, Stout JC, Aylward E, Ross CA, Nance M, Guttman M, Johnson S, MacDonald M, Beglinger LJ, Duff K, Kayson E, Biglan K, Shoulson I, Oakes D, Hayden M. Detection of Huntington's disease decades before diagnosis: the Predict-HD study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):874–880. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulsen JS, Long JD, Johnson HJ, Aylward EH, Ross CA, Williams JK, Nance MA, Erwin CJ, Westervelt HJ, Harrington DL, Bockholt HJ, Zhang Y, McCusker EA, Chiu EM, Panegyres PK. Clinical and Biomarker Changes in Premanifest Huntington Disease Show Trial Feasibility: A Decade of the PREDICT-HD Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:78. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella D, Nowinski C, Peterman A, Victorson D, Miller D, Lai J-S, Moy C. The Neurology Quality of Life Measurement (Neuro-QOL) Initiative. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Supplement. 2011;92(Suppl 1):S28–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuro-QoL Final report. 2013 www.neuroqol.org/Resources/Resources%20documents/NeuroQOL-Final%20report-2013pdf.

- 36.PROMIS® Instrument Development and Psychometric Evaluation Scientific Standards. http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMIS_Standards_050212.pdf.

- 37.Shoulson I, Fahn S. Huntington Disease - Clinical Care and Evaluation. Neurology. 1979;29(1):1–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huntington Study Group Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord. 1996;11(2):136–142. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthen B. Contributions to Factor-Analysis of Dichotomous Variables. Psychometrika. 1978;43(4):551–560. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthen B, Du Toit SHC, Spisic D. Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. 1997 https://www.statmodel.com/download/Article_075.pdf.

- 41.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Second Edition. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bentler PM. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald RP. Test theory: a unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reise SP, Morizot J, Hays RD. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):19–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT's unidimensionality assumption. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):447–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samejima F, van der Liden WJ, Hambleton R. The graded response model. In: van der Liden WJ, editor. Handbook of modern item response theory. Springer; NY, NY: 1996. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai L, Thissen D, du Toit SHC. IRTPRO for Windows [Computer software] Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Jolley L, van Belle G. Differential item functioning analysis with ordinal logistic regression techniques. DIFdetect and difwithpar. Med Care. 2006;44(11 Suppl 3):S115–123. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245183.28384.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi SW. Firestar: Computerized Adaptive Testing Simulation Program for Polytomous Item Response Theory Models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2009;33(8):644–645. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samejima F. Estimation of Latent Ability Using a Response Pattern of Graded Scores (Psychometric Monograph No. 17) Psychometric Society; Richmond, VA: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bryant FB, Yarnold PR. Principal components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold RR, editors. Reading and understanding multivariate statistics. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Everitt BS. Multivariate analysis: The need for data, and other problems. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;126:2S7–240. doi: 10.1192/bjp.126.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorsuch RL. Factor Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clauser BE, Hambleton RK. Review of Differential Item Functioning, P. W. Holland, H. Wainer. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1994;31(1):88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirwin JL, Edwards RA. Helping patients articulate end-of-life wishes: a target for interprofessional participation. Ann Palliat Med. 2013;2(2):95–97. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2013.02.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, Marinus J, Roos RA. Thinking about the end of life: a common issue for patients with Huntington's disease. J Neurol. 2014;261(11):2184–2191. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Booij SJ, Engberts DP, Rodig V, Tibben A, Roos RA. A plea for end of-life discussions with patients suffering from Huntington's disease: the role of the physician. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(10):621–624. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, Roos RA. Perhaps the subject of the questionnaire was too sensitive: Do we expect too much too soon? Wishes for the end of life in Huntington's Disease - the perspective of European physicians. J Huntingtons Dis. 2014;3(3):229–232. doi: 10.3233/JHD-140098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dellefield ME, Ferrini R. Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care: lessons learned from a cohort of nursing home residents with advanced Huntington disease. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43(4):186–192. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182212a52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams JK, Erwin C, Juhl AR, Mengeling M, Bombard Y, Hayden MR, Quaid K, Shoulson I, Taylor S, Paulsen JS. In their own words: reports of stigma and genetic discrimination by people at risk for Huntington disease in the International RESPOND-HD study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(6):1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boersma I, Miyasaki J, Kutner J, Kluger B. Palliative care and neurology: time for a paradigm shift. Neurology. 2014;83(6):561–567. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tibben A. Predictive testing for Huntington's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72(2-3):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duff K, Paulsen JS, Beglinger LJ, Langbehn DR, Wang C, Stout JC, Ross CA, Aylward E, Carlozzi NE, Queller S. “Frontal” behaviors before the diagnosis of Huntington's disease and their relationship to markers of disease progression: evidence of early lack of awareness. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(2):196–207. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.22.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]