Abstract

Coxiella burnetii is a gram-negative bacterium that is the etiologic agent of the zoonotic disease Q fever. Common reservoirs of C. burnetii include sheep, goats, and cattle. These animals shed C. burnetii into the environment, and humans are infected by inhalation of aerosols. A survey of 1622 environmental samples taken across the United States in 2006–2008 found that 23.8% of the samples contained C. burnetii DNA. To identify the strains circulating in the U.S. environment, DNA from these environmental samples was genotyped using an SNP-based approach to derive sequence types (ST) that are also compatible with multispacer sequence typing methods. Three different sequence types were observed in 31 samples taken from 19 locations. ST8 was associated with goats and ST20 with dairy cattle. ST16/26 was detected in locations with exposure to various animals and also in locations with no direct animal contact. Viable isolates were obtained for all three sequence types, but only the ST20 and ST16/26 isolates grew in acidified citrate cysteine medium (ACCM)-2 axenic media. Examination of a variety of isolates with different sequence types showed that ST8 and closely related isolates did not grow in ACCM-2. These results suggest that a limited number of C. burnetii sequence types are circulating in the U.S. environment and these strains have close associations with specific reservoir species. Growth in ACCM-2 may not be suitable for isolation of many C. burnetii strains.

Keywords: : Coxiella, genetics, reservoir host, Q fever, zoonotic

Introduction

Coxiella burnetii is an intracellular bacterium that naturally grows in eukaryotic host cells and causes the disease Q fever (Maurin and Raoult 1999). It is transmitted by inhalation, has impressive stability in the environment, and has a very low infectious dose. These properties have made C. burnetii a potential agent of bioterrorism and led to its testing as a bioweapon (Madariaga et al. 2003). Q fever is an underdiagnosed disease in the United States, with 3.1% seroprevalence in the United States, but only 100–200 cases reported to the CDC annually (Anderson et al. 2009, 2013). This is likely due to the nonspecific symptoms of the flu-like acute disease, a difficult diagnostic protocol, and a fairly high proportion of mild or asymptomatic cases (estimated at >50%) (Maurin and Raoult 1999). Q fever is most often diagnosed in the context of outbreaks, which can be quite severe. A series of outbreaks in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2010 resulted in over 4000 confirmed cases of Q fever with a hospitalization rate of 20% (van der Hoek et al. 2012).

C. burnetii can use a wide variety of animals as hosts (McQuiston and Childs 2002). Transmission of C. burnetii to humans is often associated with exposure to the waste products of infected livestock. Sheep, goats, and cattle can shed C. burnetii in urine, milk, feces, and birth products. The large outbreaks in the Netherlands were linked to shedding of C. burnetii from birthing goats (van der Hoek et al. 2012). Livestock do not typically show overt symptoms when infected, with the exception being that C. burnetii infection can lead to abortion or stillbirth, particularly when introduced into naive herds of goats or sheep. Poor pregnancy outcomes are associated with very high replication of C. burnetii in the placenta, and parturition can release large amounts of infectious C. burnetii into the environment. Exposure to birth products of infected animals represents a high risk for human acquisition of Q fever.

Nonreplicating C. burnetii form a spore-like small cell variant (SCV) that is very resistant to a variety of harsh conditions (McCaul and Williams 1981). The ease with which the SCV can spread through wind or be carried by small animals has resulted in widespread distribution in the environment. A previous study collected 1622 environmental samples from across the United States and found that C. burnetii DNA was detectable by PCR in 23.8% of the samples (Kersh et al. 2010). The percentage of positive samples was higher in locations with a livestock presence, but 18% of samples collected at locations without livestock were positive. On an average, samples collected at locations with livestock had higher concentrations of C. burnetii DNA (Kersh et al. 2010).

Recent efforts at genetic typing of C. burnetii have included multi-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis and multispacer sequence typing (MST) analyses (Massung et al. 2012). A rapid, SNP-based approach was recently described that identified a small set of canonical SNPs that can define lineages in the C. burnetii phylogeny (Keim et al. 2004, Hornstra et al. 2011). The usage of SNPs found at loci previously used for MST allows results from SNP typing to be easily compared to MST results. These analyses have demonstrated over 30 sequence types (STs) for C. burnetii, with some specific types closely associated with disease (Glazunova et al. 2005, Hornstra et al. 2011). For example, MST typing has been used to link the Netherlands epidemic to ST33 (Tilburg et al. 2012), although other genotypes may also have been involved (Huijsmans et al. 2011).

Although C. burnetii grows naturally only in host cell vacuoles, a growth medium has been developed, which allows C. burnetii to be cultured in the laboratory in the absence of host cells (Omsland et al. 2009). The first version of this media, acidified citrate cysteine medium (ACCM), was developed using the Nine Mile Phase 2 strain of C. burnetii (Omsland et al. 2009). A subsequent version (ACCM-2) supported improved growth and was shown to be effective for the virulent Nine Mile Phase 1 and Q212 C. burnetii isolates (Omsland et al. 2011). It has been demonstrated that C. burnetii can be isolated from a clinical sample using ACCM-2 (Boden et al. 2015), but whether ACCM-2 is effective for isolation of all contemporary sequence types is not known.

The previously established collection of environmental samples provided an opportunity to estimate the diversity of C. burnetii sequence types circulating in the United States. SNP-based genotyping assays were applied to environmental DNA samples that had previously been identified as positive for C. burnetii DNA (Kersh et al. 2010). This analysis evaluated the number of sequence types found in the United States and correlated the sequence types to reservoir species. The study also examined the capacity of ACCM-2 to support growth of C. burnetii sequence types found in the U.S. environment.

Materials and Methods

Environmental samples were collected with assistance from local public health staff as described previously (Kersh et al. 2010). The samples were collected as bulk samples (which was typically soil or bedding taken from the ground surface), vacuum samples (vacuumed dust collected in a HEPA filter bag), or sponge samples (surface material collected with a sponge wipe). The samples were collected in six states, at three sites per state. Approximately 90 samples were collected at each of the 18 sampling sites. Samples were stored at −80°C until DNA was isolated using the QIAmp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described (Fitzpatrick et al. 2010). Eluted DNA was stored at −20°C until SNP analysis was performed.

Of the 1622 environmental samples collected for the previous study in 2006–2008, 386 were PCR positive. Among the positive samples, 331 had a C(t) of 34 or greater using the multicopy IS1111 PCR target (Loftis et al. 2006) and were deemed unlikely to yield amplification results using the less sensitive, single-copy target SNP assays. SNP-based typing was attempted on the DNA derived from the 55 samples with a C(t) less than 34. Even with this cutoff, many of the samples had DNA concentrations too low to obtain an unambiguous result on the genotyping assays. To increase the amount of the relevant target DNA, target loci were amplified by PCR before running the genotyping assays. The SNPs used for genotyping are contained within loci defined by Glazunova et al. (2005) for MST analysis. Primers defined in the previous MST method were used to amplify SNP-containing loci. PCR products were then subjected to melt-MAMA or TaqMan genotyping assays as described previously (Hornstra et al. 2011). Using this “nested SNP assay” approach, SNP identities were tested at six different loci (Cox22bp118, Cox22bp91, Cox57bp327, Cox56bp10, Cox51bp356, and Cox51bp67) for the 55 low C(t) samples. For some of the environmental DNA samples, no SNP results were obtained, but for 31 samples, sequence types were able to be assigned as previously described (Hornstra et al. 2011) based on results at 2–6 SNP assays.

To isolate viable C. burnetii from environmental samples, five grams of bulk environmental material (soil, bedding, or contents of a vacuum cleaner bag) was mixed with 10 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and samples were incubated at room temperature with rocking for 1 h. After centrifugation for 5 min at 200 × g to remove the larger particles, the supernatants were saved and then centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 × g to concentrate the microorganisms. The supernatants were then discarded, and pellets were resuspended in 1 mL PBS. Five hundred microliters of this suspension was then injected intraperitoneally into male Balb/c mice. After 12 days, the mice were euthanized; spleens were removed, the splenocytes dissociated, and suspended in 6 mL PBS. One milliliter of the suspension was then placed on RK13 cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 5% fetal bovine serum. The culture was passed weekly and a 200 μL sample was taken at each passage. DNA was extracted from the 200 μL sample using the QIAmp DNA mini kit (Qiagen), and the genome equivalents of C. burnetii present were determined by real-time PCR targeting com1 (Kersh et al. 2010). Cultures that appeared infected visually and had two consecutive weekly samples demonstrate increasing genomic equivalents of C. burnetii and were considered to be infected by a new C. burnetii isolate. Animal procedures were approved by the CDC IACUC.

To test the growth of C. burnetii isolates in ACCM-2 media, concentrated stocks of C. burnetii were prepared by culturing the strains on RK-13 rabbit kidney cells for several weeks until C. burnetii organisms were released into the culture supernatant. Culture supernatant was harvested and washed, and the pelleted C. burnetii was resuspended in a small volume of sucrose phosphate glutamate (219 mM sucrose, 3.8 mM KH2PO4, 8.6 mM Na2HPO4, 4.9 mM glutamic acid, pH 7.0) to create stocks of the C. burnetii isolates. The stocks were frozen at −80°C. The identity and purity of the isolates were confirmed by genotyping and plasmid typing of the stocks.

Plasmid typing was performed using specific Taqman real-time PCR assays that target the QpH1, QpRS, a “general” plasmid sequence that is present in QpRS, QpH1, and the genome of strains that do not have a plasmid, but have plasmid sequences integrated into the chromosome. Because the QpRS plasmid assay also detects the QpDG plasmid, primers specific for QpDG were also designed and tested using SYBR green PCR. Isolates positive for both the QpRS and QpDG assays were considered to have the QpDG plasmid, and isolates positive for QpRS, but negative for QpDG, were considered to have the QpRS plasmid. An additional plasmid found in some strains of C. burnetii is QpDV. Strains with this plasmid would be expected to be negative for all of the PCR assays used. All strains tested had a positive result for at least one plasmid assay, suggesting that none contained QpDV. Primers and probes were as follows: QpH1 forward-5′-AAT CGA CCC GAT GTC AAC TCT AG-3′, QpH1 reverse-5′-CTG TCT AAT TCG ACC TAA AAG ATC CTC TT-3′, QpH1 probe-5′-FAM-CA GCT TAT TTC GCC CTC GCT GAC G-BHQ1-3′; QpRS forward-5′-TTC AAT AAC TGT TTA ACC AGC GTA GTC T-3′, QpRS reverse-5′-GAG CCG AGG AAA ACC ATT CA-3′, QpRS probe-5′-TET-AA CTT GTC GCG GCC CAG CAA GAA-BHQ1-3′; general forward-5′-AAA CTT CTT TGC CCA GGT GGT A-3′, general reverse-5′-TCA CAC TCG ACT CTC AGC CAT T-3′, general probe-5′-HEX-AA ATT GGC GCATCG ACC GTC GA-BHQ1-3′; and QpDG forward-5′-GCG TGT TTG CCA TTG TCT GT-3′, QpDG reverse-5′-TAA AAC AAG CAC AAG GCG GC-3′. Primers were used at a final concentration of 500 nM, and probes were used at 200 nM. Cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Melt curves for the QpDG SYBR green assay showed a dissociation of the PCR product at 80°C.

Growth in ACCM-2 was measured by inoculation of T-25 flasks containing 7 mL of ACCM-2 with stocks of each C. burnetii isolate obtained from growth in RK-13 cell cultures as described above. Starting concentrations in the cultures were evaluated by PCR targeting com1 (Kersh et al. 2010) and kept between 5 × 105 and 6 × 106 genome equivalents per mL to minimize the impact of starting density on differences in growth (Kersh et al. 2011). Four separate flasks with starting densities in the range described were created for each isolate. The media formulation and growth conditions were performed as described by Omsland (2011). ACCM-2 was stored at 4°C and used within 3 weeks of its production. A 200 μL sample of the culture was taken immediately after inoculation and then again 7 days later after incubation at 37°C, 2.5% O2, 5% CO2, and 92.5% N2. The samples were extracted using the QIAmp DNA mini kit tissue protocol (Qiagen) and DNA was quantitated using real-time PCR targeting the com1 gene (Kersh et al. 2010).

Fold change for growth in ACCM-2 was calculated as the ratio of the genome equivalents measured at day 7 to that measured at day 0. Because these ratios are highly skewed, we compared the strains’ growths over this time period using the logarithms of the fold changes. Individual means and 95% Student-t confidence intervals were computed for log fold changes by strain; for ease of interpretation, results are reported on the original scale. Fold changes among strains were compared in a regression model using generalized least squares to account for differing variances, and all pairwise comparisons were made using Tukey's method. Analyses were performed using R version 3.2.3 (www.R-project.org).

Results

To better understand the C. burnetii sequence types circulating in the United States, SNP typing was performed on DNA derived from a subset (n = 55) of the 1622 environmental samples collected in 2006–2008 (Kersh et al. 2010). The 55 samples in the subset were chosen because these samples had the highest amounts of C. burnetii DNA based on low C(t) values (<34 for IS1111 PCR). However, not all of these 55 samples had DNA quantity and quality high enough for unambiguous typing. It was only possible to assign sequence types to 31 of these environmental samples.

Three sequence types detected among the 31 typed samples segregated into three groups: ST8, ST16/26, and ST20 (Table 1). The ST16/26 group represents two MLST sequence types that cannot be further resolved using our current SNP assays. One sample in the ST8 group could not be definitively placed in ST8 due to lack of a result on the Cox51bp67 SNP assay. The 31 samples were derived from 19 different locations representing different regions of the country, with 1–4 samples typed at each of the 19 locations. None of the locations yielded multiple sequence types. Five of the locations had samples that were ST8, and one additional location produced a sample that was either ST8 or a closely related genotype (Table 1). Four of the locations where ST8 was found had a clear association with goats and the other two were associated with livestock that included goats. Eight of the locations had samples that were characterized as ST16/26. Three of these locations had multiple species of livestock, one had cattle, one had sheep, and three locations did not have direct animal exposure. Five locations had samples typed as ST20 and all five of these were dairy cattle farms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequence Types Obtained for Environmental Samples

| Location | Sequence type | Number of typed samples | Animals present | Types of samples | Regiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goat dairy | 8 | 5 | Goats | Bulk (5) | WC |

| University goat facility | 8 | 2 | Goats | Bulk (2) | WC |

| Vet hospital | 8 | 1 | Various livestock | sponge | RM |

| Horse ranch | 8 | 3 | Goats/Horses | Bulk (3) | RM |

| Farm | 8 | 3 | Goats/Cattle | Bulk (3) | MW |

| Barn at Fairgrounds | 8–10/27–28/31 | 1 | Various livestock | sponge | SC |

| County government building | 16/26 | 1 | none | sponge | RM |

| Farm and Ranch Co-op | 16/26 | 1 | none | sponge | RM |

| State government building | 16/26 | 1 | none | sponge | RM |

| Ranch | 16/26 | 1 | Sheep | bulk | RM |

| Animal hospital | 16/26 | 1 | Various | bulk | EC |

| Fairgrounds | 16/26 | 1 | bulk | MW | |

| Cattle feedlot | 16/26 | 1 | Cattle | bulk | SC |

| University Experiment Station | 16/26 | 1 | Various livestock | bulk | SC |

| Cattle dairy farm | 20 | 1 | Cattle | sponge | RM |

| Cattle dairy farm | 20 | 4 | Cattle | Bulk (4) | DS |

| Cattle dairy farm | 20 | 2 | Cattle | Bulk (1), vacuum (1) | SC |

| Cattle dairy farm | 20 | 4 | Cattle | Bulk (4) | SC |

| Cattle dairy farm | 20 | 1 | Cattle | bulk | MW |

Regions are defined as: WC, west coast; RM, rocky mountain; MW, midwest; SC, south central, EC, east coast; DS, deep south.

Three viable isolates were obtained from the environmental samples. One typed as ST8, one as ST16/26, and one as ST20. The ST8 isolate (ES-CA1) was derived from a bulk sample taken at a university goat facility, the ST16/26 isolate (ES-VA1) was derived from a bulk sample taken from a vacuum cleaner at an animal hospital that treated a variety of species, and the ST20 isolate (ES-FL1) was derived from a bulk soil sample taken at a dairy cattle ranch. Each of the isolates had the plasmid that has been previously associated with their sequence types (Beare et al. 2009, Loftis et al. 2010, Kersh et al. 2013) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Viable C. burnetii Isolates from Environmental Samples

| Isolate name | ES-FL1 | ES-VA1 | ES-CA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Soil sample from cattle dairy | Vacuum cleaner at animal hospital | University goat facility |

| Sample type | bulk | bulk | Bulk |

| Animal exposure | cattle | various | Goats |

| Sequence type | 20 | 16/26 | 8 |

| Plasmid | QpH1 | QpH1 | QpRS |

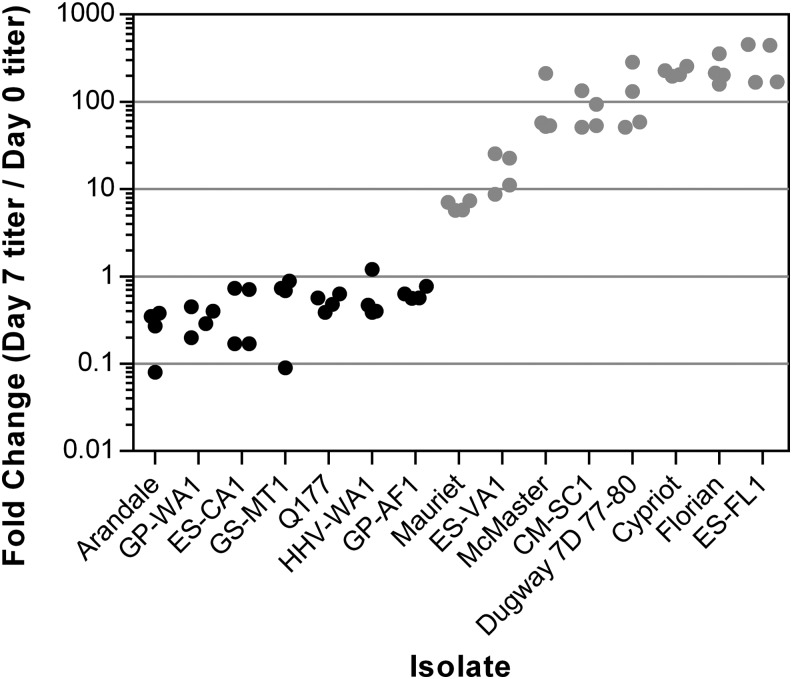

After isolation of C. burnetii from environmental samples using mice and RK-13 tissue culture cells, the isolates were grown in ACCM-2 axenic media to produce host cell-free bacterial stocks. It became clear that the ES-FL1 (ST20) and ES-VA1 (ST16/26) isolates grew well in ACCM-2, but ES-CA1 (ST8) did not grow at all. To determine if poor growth in ACCM-2 was a general feature of ST8 isolates and which other isolates and sequence types may not grow in ACCM-2, multiple isolates were tested for growth. Flasks of ACCM-2 were inoculated with between 5 × 105 and 6 × 106 genome equivalents of C. burnetii per mL, and the fold expansion after 1 week was calculated. As shown in Table 3, the environmental ST8 isolate ES-CA1 had a reduction in genome equivalents after 1 week. Similarly, three other ST8 isolates, GP-WA1, GS-MT1, and Q177, also had a reduction in genome equivalents after 1 week in ACCM-2 culture. The HHV-WA1 and Arandale isolates are in the ST1–7/30 group of genotypes and also had fewer organisms after culture. The GP-AF1 isolate (ST9–10/27–28/31) has a sequence type closely related to ST8 and it also did not grow in ACCM-2. All of these isolates grew well in the mammalian host cell RK-13, suggesting the growth defect was specific for axenic culture.

Table 3.

Growth of C. burnetii Strains in ACCM-2

| Strain | Sequence type | Origin | Plasmid | Mean fold change (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHV-WA1 | 1–7/30 | Human heart valve | QpRS | 0.55 (0.23, 1.29) |

| Arandale | 1–7/30 | Human acute Q fever | QpRS | 0.23 (0.07, 0.74) |

| Q177 | 8 | Goat | QpRS | 0.51 (0.37, 0.70) |

| GP-WA1 | 8 | Goat placenta | QpRS | 0.32 (0.18, 0.57) |

| ES-CA1 | 8 | Goat farm | QpRS | 0.35 (0.09, 1.32) |

| GS-MT1 | 8 | Goat vaginal swab | QpRS | 0.45 (0.08, 2.44) |

| GP-AF1 | 9–10/27–28/31 | Goat placenta | QpRS | 0.63 (0.49, 0.80) |

| Dugway 7D 77–80 | DG | Utah rodent | QpDG | 103.49 (29.12, 367.78) |

| Mauriet | 11–15/24/32–34 | Human | QpH1 | 6.46 (5.22, 8.00) |

| ES-VA1 | 16/26 | Animal hospital | QpH1 | 15.36 (6.65, 35.46) |

| Cypriot | 16/26 | Cyprus | QpH1 | 220.78 (181.93, 267.93) |

| CM-SC1 | 20 | Cow milk | QpH1 | 76.50 (36.53, 160.19) |

| ES-FL1 | 20 | Cow dairy soil | QpH1 | 275.75 (112.20, 677.69) |

| McMaster | 21 | Human placenta | none | 76.33 (25.74, 226.33) |

| Florian | 22–23/29 | Human acute Q fever | QpH1 | 222.98 (130.65, 380.56) |

ACCM, acidified citrate cysteine medium; CI, confidence interval.

In contrast, eight isolates falling into genotype groups ST21, ST16/26, ST20, ST22–23/29, ST11–15/24/32–34, and STDugway had significant expansion in ACCM-2. The two environmental isolates that were not ST8, ES-VA1 (ST16/26), and ES-FL1 (ST20), grew in ACCM-2 with 15- and 276-fold expansion, respectively. To evaluate if differences between isolate growth were statistically significant, Tukey pairwise comparisons were obtained based on the regression model of log fold change accounting for unequal variances. This resulted in a complex pattern of statistically significant differences among the 91 pairs of isolates. A simplified representation of these results is obtained by ordering the isolates by the mean log fold change and grouping those sets of pairs that did not differ statistically and then identifying gaps to indicate separation of isolates (Fig. 1). These results suggest the isolates can be reasonably separated into two groups representing isolates that may be considered “nongrowing” and “growing.” There were some differences among the ACCM-2 compatible isolates. The Mauriet and ES-VA1 isolates grew in ACCM-2, but both achieved less than 20-fold expansion. In contrast, the other “growing” isolates had growth that ranged from 76- to 276-fold expansion under these conditions.

FIG. 1.

Growth of Coxiella burnetii isolates in ACCM-2. The log of the fold change in genome equivalents is plotted for each of the isolates tested. Each dot represents an individual flask. Based on the pairwise comparisons, the isolates can be grouped into two groups: isolates that do not grow in ACCM-2 (black dots) and isolates that grow in ACCM-2 (gray dots). ACCM, acidified citrate cysteine medium.

Examination of the C. burnetii phylogenetic tree reveals that there are two main clades of C. burnetii genotypes emanating from the root (Fig. 2) (Pearson et al. 2013). Isolates that grow well in ACCM-2 are on one of the main branches of the tree, whereas the isolates that do not grow well are on the other branch. All of the isolates that do not grow in ACCM-2 bear the QpRS plasmid. The isolates that do grow in ACCM-2 have either the QpH1 or QpDG plasmid, or in the case of the McMaster and Q212 (Omsland et al. 2011) isolates, have plasmid-like sequences incorporated into the chromosome.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of C. burnetii isolates showing growth of the isolates in ACCM-2 axenic media. Isolates that fall into the different sequence type groups are indicated and the fold change in growth in ACCM-2 (taken from Table 3) is shown. Isolates that do not grow in ACCM-2 are all on the upper branch of the tree, and growing isolates are all on the lower branch.

Discussion

The association of genotypes with reservoir species is striking in these data, particularly for ST8 and ST20. The ST8 genotype is not only associated with goats in these data, but strains of this genotype have also been isolated from goats in the Western United States previously (Hornstra et al. 2011), been found in goat milk (Pearson et al. 2014), and associated with goats in a 2011 human Q fever outbreak occurring in Washington and Montana (Kersh et al. 2013). ST8 strains have also been isolated from a number of human heart valves taken from chronic Q fever endocarditis patients in the United States, France, and Spain (Glazunova et al. 2005, Hornstra et al. 2011). Other C. burnetii sequence types have been found associated with goats in other parts of the world.

The ST20 genotype has a very close association with dairy cattle in these data. A linkage between ST20 and dairy cattle has also been noted previously in the United States and Europe (Tilburg et al. 2012, Pearson et al. 2014). A worldwide connection between ST20 and dairy cattle is possible, although many parts of the world have not been tested. However, the linkage between ST20 and dairy cows has been found wherever the testing has been performed. The tight association between ST20 and dairy cows could be due to the relatively limited amount of testing that has been done or it could be that ST20 strains have adapted well enough to dairy cows to be able to exclude other sequence types from this population. The close association of ST20 with dairy cattle that is currently observed appears to be a recent phenomenon; other sequence types were found in cattle as recently as 23 years ago (Glazunova et al. 2005, Hornstra et al. 2011). In contrast to the ST8 genotype, the ST20 genotype has not been associated with human disease in the United States (Hornstra et al. 2011, Kersh et al. 2013). Reasons for the absence of ST20 isolates from human disease cases in the United States could be due to the relative infrequency of strain genotyping in Q fever patients, a reduced ability of ST20 strains to cause human disease, or because the cow does not shed C. burnetii in such a way as to easily infect people. Isolates typed as ST20 have been derived from human chronic Q fever cases in France, suggesting either that heterogeneity between United States and European ST20 strains exists or that genotyping larger numbers of isolates in the United States may reveal ST20 associated with human disease.

For ST16/26, the primary reservoirs are not clear from these data. ST16/26 DNA was found at locations with cattle and sheep and also found at places with no direct animal presence. Previously, ST16/26 isolates have been derived from patient samples, ticks, and in cow milk before 1990 (Glazunova et al. 2005, Hornstra et al. 2011). These data do not indicate that dairy cattle are the contemporary reservoir for ST16/26 in the United States, as this sequence type was never observed at locations that had only dairy cows. Sheep are a possible reservoir for ST16/26 strains, but also beef cattle, rodents, and other wildlife.

The failure of many isolates to grow in ACCM-2 was surprising. The ACCM and ACCM-2 media were developed using the Nine Mile Phase 2 isolate (ST16/26) and shown to work well for the Nine Mile Phase 1 (ST16/26) and Q212 (ST21) isolates (Beare et al. 2009, Omsland et al. 2011). In a previous study, we observed that the ST8 isolate Q154 did not grow in ACCM, but the ST8 isolate Q177 grew in that media. However, subsequent analysis revealed that the stock of Q177 used in the previous study was contaminated with another genotype of C. burnetii. For the data in this study, a new stock of Q177 was used whose purity was confirmed by genotyping. The new stock of Q177 does not grow in ACCM-2, and zero growth was observed for all other isolates tested on the upper branch of the C. burnetii tree (Fig. 2). This includes isolates in the ST1–7/30, ST8, and ST9–10/27–28/30 groups.

One feature of the strains that fail to grow in ACCM-2 is that they all have the QpRS plasmid. At this point, it is not clear if genetic differences that determine whether C. burnetii isolates will grow in ACCM-2 reside on the plasmid or the chromosome. There are strains on the upper branch of the tree (ST1–ST4) that have the QpDV plasmid. Testing of these strains for growth in ACCM-2 could be informative, but currently, the identity of C. burnetii gene sequences that influence growth in ACCM-2 is yet to be determined. Among the ACCM-2 compatible strains, there was some variability in fold expansion. The ES-VA1 and Mauriet isolates expanded significantly less than the other isolates in the “growing” category. Reduced viability in the stocks of these isolates is a possibility, but they were prepared in the same way as the other isolates. Starting concentrations for ES-VA1 and Mauriet were between 1 × 106/mL and 4 × 106/mL, which were very similar to other “growing” isolates. Genetic differences may be present, which reduce expansion and/or viability of these isolates.

A different analysis of the fold changes using statistical clustering methods to identify grouping of isolates resulted in qualitatively equivalent results. Only minor differences were seen between these clustering methods’ results and those reported above for the isolates “on the boundary” of the identified growers and nongrowers groupings, and these grouping assignments differed slightly depending on the clustering method used. Further, the pairwise comparisons presented useful information about the uncertainty in the estimates of the mean fold changes, whereas the clustering methods did not. We therefore retained the pairwise comparison results as a more accurate analysis of these data.

The lack of growth for some isolates in ACCM-2 suggests that this medium has limitations and should not be used as the sole method for isolation of C. burnetii. The medium appears capable of strong selection for sequence types that are closely related to Nine Mile, and use of this medium in isolation attempts would likely fail to grow many of the strains found in patient and animal samples. In ACCM-2 cultures that contain more than one genotype, a strain with only a slight growth advantage can completely take over the culture in one or two passages (data not shown). More traditional methods such as host cell culture, animal inoculation, or growth in embryonated eggs are likely to be needed to ensure that all genotypes are represented in isolated strains of C. burnetii.

These data demonstrate limited diversity of C. burnetii sequence types in the contemporary United States and a close association between reservoir species and specific sequence types. The amount of diversity within the ST8 and ST20 sequence types is not currently known, and higher resolution genotyping may reveal significant diversity within these identified types. Additional work is needed to further subdivide the isolates contained in these groups and investigate additional samples from other locations to determine any geographic limitations of these relationships. Finally, the presence of viable C. burnetii in bulk environmental samples reinforces the idea that close contact with reservoir animals is not required for C. burnetii infection and environmental C. burnetii represents an infectious risk even if the reservoirs are not present.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the local health officials and landowners who participated in the original collection of the environmental samples. This work was funded, in part, by the Department of Homeland Security (HSHQDC-10-C-00139). We would also like to thank Robert Heinzen (NIH/NIAID) and Stephen Graves (Australian Rickettsial reference Laboratory) for providing isolates. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Anderson A, Bijlmer H, Fournier PE, Graves S, et al. Diagnosis and management of Q fever—United States, 2013: recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013; 62:1–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AD, Kruszon-Moran D, Loftis AD, McQuillan G, et al. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 81:691–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare PA, Unsworth N, Andoh M, Voth DE, et al. Comparative genomics reveal extensive transposon-mediated genomic plasticity and diversity among potential effector proteins within the genus Coxiella. Infect Immun 2009; 77:642–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden K, Wolf K, Hermann B, Frangoulidis D. First isolation of Coxiella burnetii from clinical material by cell-free medium (ACCM2). Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015; 34:1017–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KA, Kersh GJ, Massung RF. Practical method for extraction of PCR-quality DNA from environmental soil samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010; 76:4571–4573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazunova O, Roux V, Freylikman O, Sekeyova Z, et al. Coxiella burnetii genotyping. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:1211–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornstra HM, Priestley RA, Georgia SM, Kachur S, et al. Rapid typing of Coxiella burnetii. PLoS One 2011; 6:e26201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijsmans CJ, Schellekens JJ, Wever PC, Toman R, et al. Single-nucleotide-polymorphism genotyping of Coxiella burnetii during a Q fever outbreak in The Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011; 77:2051–2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Van Ert MN, Pearson T, Vogler AJ, et al. Anthrax molecular epidemiology and forensics: using the appropriate marker for different evolutionary scales. Infect Genet Evol 2004; 4:205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh GJ, Fitzpatrick KA, Self JS, Priestley RA, et al. Presence and persistence of Coxiella burnetii in the environments of goat farms associated with a Q fever outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:1697–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh GJ, Lambourn DM, Self JS, Akmajian AM, et al. Coxiella burnetii infection of a Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) found in Washington State. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48:3428–3431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh GJ, Oliver LD, Self JS, Fitzpatrick KA, et al. Virulence of pathogenic Coxiella burnetii strains after growth in the absence of host cells. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11:1433–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh GJ, Wolfe TM, Fitzpatrick KA, Candee AJ, et al. Presence of Coxiella burnetii DNA in the environment of the United States, 2006 to 2008. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010; 76:4469–4475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Priestley RA, Massung RF. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in commercially available raw milk from the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2010; 7:1453–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Reeves WK, Szumlas DE, Abbassy MM, et al. Rickettsial agents in Egyptian ticks collected from domestic animals. Exp Appl Acarol 2006; 40:67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madariaga MG, Rezai K, Trenholme GM, Weinstein RA. Q fever: a biological weapon in your backyard. Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3:709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massung RF, Cutler SJ, Frangoulidis D. Molecular typing of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever). Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 984:381–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999; 12:518–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul TF, Williams JC. Developmental cycle of Coxiella burnetii: structure and morphogenesis of vegetative and sporogenic differentiations. J Bacteriol 1981; 147:1063–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuiston JH, Childs JE. Q fever in humans and animals in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2002; 2:179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omsland A, Beare PA, Hill J, Cockrell DC, et al. Isolation from animal tissue and genetic transformation of Coxiella burnetii are facilitated by an improved axenic growth medium. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011; 77:3720–3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omsland A, Cockrell DC, Howe D, Fischer ER, et al. Host cell-free growth of the Q fever bacterium Coxiella burnetii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:4430–4434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Hornstra HM, Hilsabeck R, Gates LT, et al. High prevalence and two dominant host-specific genotypes of Coxiella burnetii in U.S. milk. BMC Microbiol 2014; 14:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Hornstra HM, Sahl JW, Schaack S, et al. When outgroups fail; phylogenomics of rooting the emerging pathogen, Coxiella burnetii. Syst Biol 2013; 62:752–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilburg JJ, Roest HJ, Buffet S, Nabuurs-Franssen MH, et al. Epidemic genotype of Coxiella burnetii among goats, sheep, and humans in the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:887–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek W, Morroy G, Renders NH, Wever PC, et al. Epidemic Q fever in humans in the Netherlands. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 984:329–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]