Abstract

2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like (OASL) is a kind of antiviral protein induced by interferons (IFNs), which plays an important role in the IFNs-mediated antiviral signaling pathway. In this study, we cloned and identified OASL in the Chinese goose for the first time. Goose 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like (goOASL), including an ORF of 1527bp, encoding a protein of 508 amino acids. GoOASL protein contains 3 conserved motifs: nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) domain, 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) domain, and 2 ubiquitin-like (UBL) repeats. The tissue distribution profile of goOASL in 2-week-old gosling and adult goose were identified by Real-Time quantitative PCR, which revealed that the highest level of goOASL mRNA transcription was detected in the blood of adult goose and gosling. The mRNA transcription level of goOASL was upregulated in all tested tissues of duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV)-infected 3-day-old goslings, compared with control groups. Furthermore, using the stimulus Poly(I: C), ODN2006, R848, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as well as the viral pathogens DTMUV, H9N2 avian influenza virus (AIV), and gosling plague virus (GPV) to treat goose peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for 6 h, goOASL transcripts level was significantly upregulated in all treated groups. To further investigate the antiviral activity of goOASL, pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His plasmid was constructed, and goOASL was expressed by the goose embryo fibroblast cells (GEFs) transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His. Our research data suggested that Newcastle disease virus (NDV) replication (viral copies and viral titer) in GEFs was significantly reduced by the overexpression of goOASL protein. These data were meaningful for the antiviral immunity research of goose and shed light on the future prevention of NDV in fowl.

Introduction

Innate immunity is the first line of host defense against invading pathogens (Schoggins and Rice 2011). The host innate immune responses to prevent viral infection can be focused on inhibiting viral proteins' biosynthesis or degrading viral nucleic acids. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors, which promote the activation of interferon regulatory factors and transcription of interferons (IFNs), then IFNs bind to its cognate receptor, which subsequently increases the expression of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like (OAS) (Hovanessian and others 1977; Kerr and Brown 1978; Pichlmair and Sousa 2007).

The OAS belongs to a nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) family. The 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like (OASL) is a member of OAS superfamily and an IFN-induced cellular protein. In human beings, there are 4 OAS proteins, OAS1, OAS2, OAS3, and OASL, but OASL does not have OAS catalytic activity (Hartmann and others 1998, 2003; Kakuta and others 2002; Eskildsen and others 2003; Hovanessian and Justesen 2007). Similarly, in mouse, there are 5 OAS proteins, OAS1, OAS2, OAS3, OASL1, and OASL2. Different from human OASL (huOASL) and mouse OASL1 (mOASL1), mouse OASL2 (mOASL2) has OAS catalytic activity (Ghosh and others 1991; Kakuta and others 2002; Eskildsen and others 2003). In chicken, only OASL protein was identified (Kjaer and others 2009), which was subdivided into OAS*A and OAS*B (Yamamoto and others 1998; Tatsumi and others 2000), both of them have OAS catalytic activity (Yamamoto and others 1998; Tatsumi and others 2000, 2003; Kakuta and others 2002; Eskildsen and others 2003; Tag-El-Din-Hassan and others 2012). However, no OAS or OASL in aquatic bird has been reported yet. In this study, the cDNA of Chinese goose OASL is identified and characterized for the first time. The tissue expression profiles of goOASL in 2-week-old and adult bird were detected. Furthermore, the mRNA level of goOASL in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) after stimulating by pathogens, duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV), H9N2 avian influenza virus (AIV), gosling plague virus (GPV), as well as the agonist Poly(I: C), ODN2006, R848, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were detected, respectively.

As reported, the 2-5A system plays an important role in interferon-induced antiviral effects against encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), reovirus and vaccinia virus (Silverman and Cirino 1997). DTMUV is a newly discovered single-stranded RNA virus, which belongs to family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. This virus can cause economic loss and serious diseases in ducks and geese (Wu and others 2014; Ti and others 2015). The goOASL expression was explored in vivo during DTMUV infection. Newcastle disease virus (NDV) can cause serious and economically significant disease in almost all birds, including domestic fowls (Kang and others 2016), which is a negative-sense, single-stranded, and enveloped RNA virus, belonging to family Paramyxoviridae. In terms of virus in the family Paramyxoviridae, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was reported to be inhibited by human OAS1, OAS2, OASL, and mouse OASL (Behera and others 2002; Dhar and others 2015). In our study, to detect antiviral activity of goOASL in vitro, we selected goose embryo fibroblast cells (GEFs) as cell model and NDV as viral pathogen. These data manifest the immune characteristics of goOASL, facilitate a better understanding of the role of goOASL played in host defense immunity, and provide tools for future immunopathological and functional studies.

Materials and Methods

Animals, cells, virus, and stimulants

The geese (Sichuan white goose, Anser cygnoides) in experiments were obtained from the Sichuan Agricultural University (Ya'an city, Sichuan Province). They were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for 3 days with water and fodder before experiments. Goose embryo fibroblast (GEF) cells from 9-day-old embryonated eggs obtained from the Sichuan Agricultural University (Ya'an city, Sichuan Province) were prepared using standard dissociation procedures with trypsin (Gibco). The DTMUV (6.3 × 10−6 TCID50/mL) (Zhu and others 2015) and GPV (10−6.6 EID50/0.2 mL) (Chen and others 2015) were provided by the Avian Diseases Research Center of Sichuan Agricultural University. The AIV strain (7.14 × 1012.64 copies/mL) and the goose origin NDV (10−5.67TCID50/0.1 mL) used in this study were kindly provided by the Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Agonists are R848 (MedChem Express), LPS (Invivogen), Poly (I: C) (Sigma), and ODN2006 (Sangon).

RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

Total RNA from various tissues and cells was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Virus RNA was extracted using the TIANamp Virus DNA/RNA Kit (Tiangen). The cDNA was synthesized using the HiScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA templates of all different samples were stored at −80°C until used.

Cloning of goOASL

The degenerate primers of goOASL were designed based on the conserved regions of Gallus gallus OAS*B (reference sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1) and our transcriptome data of goose spleen (Wang and others 2015). The partial sequence of goOASL was amplified with the primers GoOASL-F and GoOASL-R (all primers used in this study are listed in Table 2). The procedure of PCR amplification is as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 61°C and extension at 72°C for 1 min, and at the end of the thermal cycling, a further extension at 72°C for 7 min following the last cycle. The PCR products were cloned into the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) followed by sequencing to confirm. The full-length cDNA sequences of goOASL were gained using 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA end (RACE) PCRs. Based on the partial sequence obtained, the gene-specific primers (GSPs), including GoOASL-3GSP1, GoOASL-3GSP2, GoOASL-5GSP0, GoOASL-5GSP1, and GoOASL-5GSP2, were designed to acquire the full-length goOASL mRNA sequence with 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs).

Table 1.

Amino Acid Identities Between GoOASL and Other Species

| Taxonomy | Species/gene | Anser cygnoides identity (%) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Aptenodytes forsteri/OASL2 | 69 | KFM04507.1 |

| Podiceps cristatus/OASL1 | 68 | KFZ55443.1 | |

| Egretta garzetta/OASL2 | 67 | KFP16354.1 | |

| Amazona aestiva/OASL2 | 68 | KQK84582.1 | |

| Columba livia/OASL2 | 66 | EMC83969.1 | |

| Caprimulgus carolinensis/OASL1 | 65 | KFZ60419.1 | |

| Phalacrocorax carbo/OASL1 | 64 | KFW92856.1 | |

| Gallus gallus/OAS*A | 63 | BAB19016.1 | |

| Cuculus canorus/OASL1 | 63 | KFO82394.1 | |

| Gallus gallus/OAS*B | 60 | NP_990372.1 | |

| Calypte anna/OASL2 | 58 | KFP04899.1 | |

| Gavia stellata/OASL1 | 55 | KFV52056.1 | |

| Reptile | Thamnophis sirtalis/predicted OASL | 45 | XP_013917049.1 |

| Mammalia | Canis lupus familiaris/OASL2 | 44 | NP_001041558.1 |

| Homo sapiens/OAS1 | 30 | BAA00047.1 | |

| Homo sapiens/OASL | 37 | AIC55448.1 | |

| Mus musculus/OASL1 | 37 | AAM08092.1 | |

| Mus musculus/OASL2 | 40 | NP-035984.2 |

Amino acid identities were analyzed using BLASTP in NCBI or DNAMAN software. Identity means complete identical amino acid pairs.

goOASL, goose 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like.

Table 2.

List of Primers

| Application | Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Partial sequence | GoOASL-F1 | CTCCCTCAGCCTCACSCTCT |

| GoOASL-R1 | CTCCAGCGTRTGGTGGTTCT | |

| RT-Qpcr | GoOASL-qF | CAGCGTGTGGTGGTTCTC |

| GoOASL-qR | AACCAGACGATGACATACAC | |

| GAPDH-qF | CATTTTCCAGGAGCGTGACC | |

| GAPDH-qR | AGACACCAGTAGACTCCACA | |

| NDV(F)-qF | CTGCGGATAGAATCACCAAGGG | |

| NDV(F)-qR | GGGAGACAAAGCAGTCAACATA | |

| 3RACE | 3RACE-AP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACT(17) |

| 3RACE-AUAP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | |

| GoOASL-3GSP1 | AAATGATCGAGCGGGAATGGAG | |

| GoOASL-3GSP2 | CGCCTGACCTACGACTCCAAG | |

| 5RACE | 5RACE-AAP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTACGGGIIGGGIIGGGIIGGGIIG |

| 5RACE-AUAP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | |

| GoOASL-5GSP0 | CCTGGCGGGTGTTGA | |

| GoOASL-5GSP1 | CAGCGTGGTGTCGTAGTAGAT | |

| GoOASL-5GSP2 | CAGGATGTCGACGTCAATGGA | |

| Full-length amplification | GoOASL-F2 | CTGCGGGAGCCGCGATGGAG |

| GoOASL-R2 | CCAGGGAGAAATAAAAGGGGATG | |

| Protein expression | ExpOASL-F | TGGTGGAATTCTGCAGATATCGCCACCATGGAGCTGCGGGACGTG |

| ExpOASL-R | GCCCTCTAGACTCGAGCGGCCGCTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGGAGGGCTGGCAGCAAGG |

Degenerate basses: S = C+G; R = G+A.

Bioinformatic analysis of sequences

The potential open reading frames (ORFs) of goOASL were analyzed by the ORF Finder in NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html), using the DNAMAN software, the ORF region was translated into the corresponding amino acids. Protein molecular weight was predicted by online server (www.sciencegateway.org/tools/proteinmw.htm). The sequence identities between goOASL and other animals were analyzed by BLASTP in NCBI or DNAMAN. The amino acid sequences of OASL and OAS from goose, chicken, human, and mouse were compared through the DNAMAN multiple sequence alignment. Protein conserved domains of goOASL were analyzed by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method.

Tissue distribution profile of goOASL

Various tissues, including the blood, brain, harderian gland, bursa of Fabricius, thymus, liver, spleen, heart, lung, small intestine, cecum, cecal tonsil, pancreas, kidney, proventriculus, gizzard, trachea, skin, and muscle were collected from gosling (2 weeks of age) and adult goose (beyond 3 months old) for Real-Time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assay.

To evaluate the mRNA expression level of goOASL in different tissues, RT-qPCR was performed with the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad) with primers of GoOASL-qF and GoOASL-qR. Amplification of goose GAPDH was used as an internal control. Reactions were carried out in triplicate. A total reaction volume of 10 μL contained 0.4 μL cDNA sample, 5.0 μL SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit), 0.3 μL of each primer (listed in Table 2), and 4.0 μL ddH2O. The amplification program was initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 39 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, and 62°C for 30 s, followed by melt curve analysis (from 65°C to 95°C with a heating rate at 0.5°C per second and a continuous fluorescence measurement). After the amplification phase, a melting curve program (from 65°C to 95°C with a heating rate of 0.5°C per second and a continuous fluorescence measurement) was routinely performed to confirm the presence of a single and specific PCR product. Standard curves were generated for each gene to estimate amplification efficiency. Finally, RT-qPCR data were analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCT method using Bio-Rad CFX Manager software.

The effects of DTMUV in the goOASL expression in vivo

The goOASL mRNA expression levels in the tissues of DTMUV-infected birds were analyzed using RT-qPCR briefly, as follows. Five 3-day-old goslings were each injected with 0.5 mL DTMUV, whereas the control group (5 goslings) was injected with 0.5 mL PBS solely. On the fifth postinfection day, all goslings were euthanized, and the immune-related organs, including harderian gland, bursa of Fabricius, trachea, spleen, lung, small intestine, cecum, and cecal tonsil, were collected for the detection of goOASL mRNA levels during the course of experimental DTMUV infection. Goose GAPDH was chosen as housekeeping gene.

The effects of pathogens and agonists in the goOASL expression in vitro

Goose PBMCs were collected and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) with 10% FBS and 5% CO2 at 37°C, the cell density was adjusted as 1 × 106/mL. Next day, the cells were stimulated by agonists, including LPS (25 μg/mL), R848 (5 μg/mL), Poly (I: C) (30 μg/mL), and ODN2006 (50 μg/mL), as well as virus pathogens, including GPV, H9N2 AIV, TMUV 50 μL, respectively, for 6 h. DTMUV, H9N2 AIV, GPV, Poly(I: C), ODN2006, R848, and LPS mimic the infection by single-stranded RNA, DNA, double-stranded RNA, double-stranded DNA, and LPS of pathogens, respectively. The cells were collected, and the total RNA of cells was extracted and cDNA synthesis was performed as previously. The mRNA expression levels of goOASL and GAPDH were quantified by RT-qPCR as described above, PBS was used as the mock infection control.

Expression plasmid construction and Western blotting confirmation

GoOASL cDNA was amplified with eukaryotic expression primers (shown in Table 2) that added EcoR V and Not I restriction sites to the PCR fragment, and then subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) expression vector that expresses a fusion protein with a C-terminal His-tag, named as pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His. Construction was verified by sequencing. The GEFs were seeded into 12-well plates with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C in a 5%CO2 atmosphere. After 12–24 h, the cell monolayer reached 80–100% confluence and was transfected with 1.6 μg/well of pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His plasmid using TransIn EL Transfection Reagent (Trans) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pcDNA3.1(+)-vector was used as a negative control. After transfection for 36 h, cells were lysed in RIPA Buffer (Thermo) and harvested. Similar volume of protein samples were electrophoresed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad). We chose goose β-actin as housekeeping protein. The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST for 1 h at 37°C. Then the blots were incubated with primary antibodies mouse monoclonal anti-His antibody (Proteintech) or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Ruiyingbio), diluted in TBST buffer containing 2.5% skim milk for 1 h at 37°C. The secondary antibody was HRP-goat anti-mouse IgG (EarthOx), incubation method the same as the first antibody. The target proteins were detected by ECL reagents (Bio-Rad).

Antiviral activity of goOASL against NDV

The GEFs were cultured in the same condition as above, transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His and pcDNA3.1(+)-Vector plasmid, respectively, as before. After 36 h transfection, cells were infected with NDV (200TCID50/well) for 24 h, then the samples were collected by 3 freeze–thaw cycles and kept in −80°C; later, the samples were used to detect NDV genome copies using specific primers (shown in Table 2) by RT-qPCR. Moreover, virus titer 50% tissue culture infective dose/0.1 mL (TCID50/0.1 mL) in each sample was also measured on GEFs with 6-days observation in 96-wells plates through the standard method of Karber.

Results

Sequence analysis of goOASL

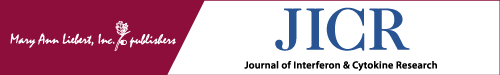

The total length of goOASL cDNA was 1642 bp in size, 5′-UTR was 19 bp, 3′-UTR was 96 bp, with a 1527 bp ORF. The cDNA sequence of goOASL (GenBank accession number KU058695) was reported here for the first time. The ORF was translated into the corresponding 508 amino acids, and the predicted molecular weight of goOASL was 58.09 kDa. The amino acid sequence identities of goOASL with other birds revealed high identity and the 508 amino acids showed low identity with other mammals and reptiles. Multiple sequence alignment of goOASL homologs by using DNAMAN software, several conserved motifs and single amino acids that associated with enzymatic activity have been indicated with different colors in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Multiple alignment analysis of OAS family amino acid sequences: Anser cygnoides, Gallus gallus, Homo sapiens, and Mus musculus. These sequences were downloaded from GenBank with accession numbers as follows: KU058695 (Anser cygnoides OASL, goOASL), BAB19016.1 (Gallus gallus OAS*A, chOAS*A), NP-990372.1 (Gallus gallus OAS*B, chOAS*B), BAA00047.1 (Homo sapiens OAS1, huOAS1), AIC55448.1 (Homo sapiens OASL, huOASL), AAM08092.1 (Mus musculus OASL1, mOASL1), and NP-035984.2(Mus musculus OASL2, mOASL2). The alignment was generated with ClustalW in DNAMAN. Amino acids conserved among all species were indicated as identical (*) and weakly conserved (.). Numbers on the right of each line showed the location of the last residue. OAS-specific motifs (P-loop, D-box, LIRL, YALELLT, and RPVILDPADP) and amino acids (K and R) were indicated in different colors. Different types of lines on sequences represented different protein domains: nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) domain, OAS domain, UBL domain. The protein prediction was performed using the program SMART. OAS, 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-like; UBL, ubiquitin-like. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jir

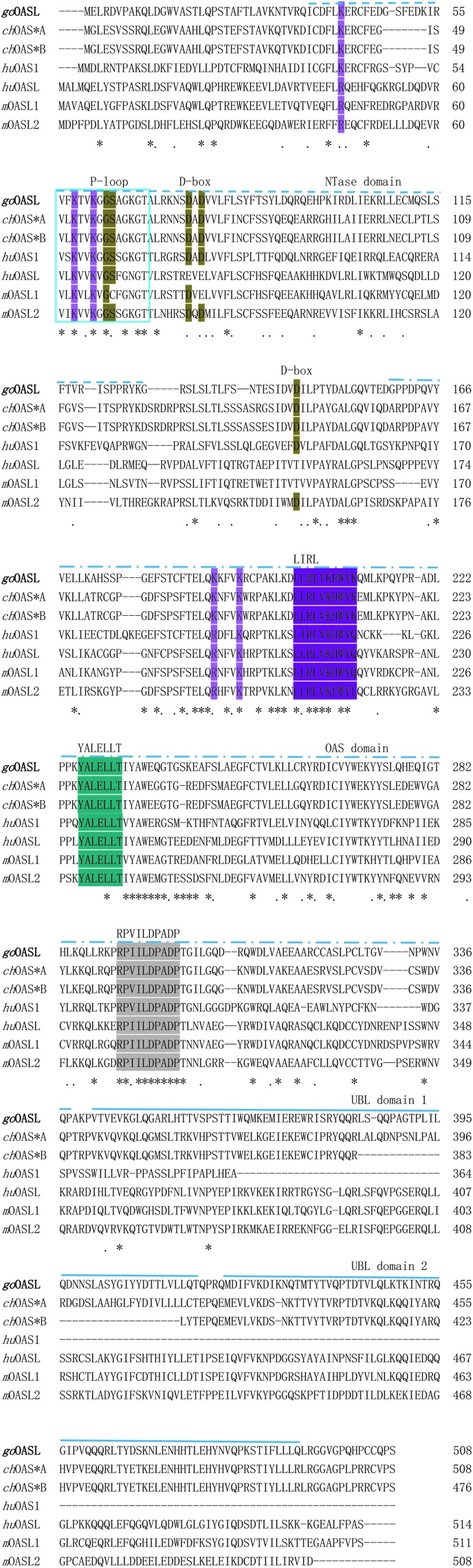

Analyzed by SMART software, domain structure of goOASL protein is similar to chicken OAS*A (chOAS*A) and chicken OAS*B (chOAS*B) proteins, their proteins are composed of 3 main domains, including NTase domain, OAS domain, and 2 ubiquitin-like (UBL) domains (marked in different types of lines, Fig. 1). Phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequence of goOASL compared with homologs in other organisms (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic tree shows that huOASL was homologous to mOASL1, then mOASL2, whereas goOASL had the homology to chOASL.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of OAS family amino acid sequences. Sequences used are listed in Table 1. Evolution analyses were conducted by MEGA6.0. Numbers in branches indicate evolutionary distances. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method.

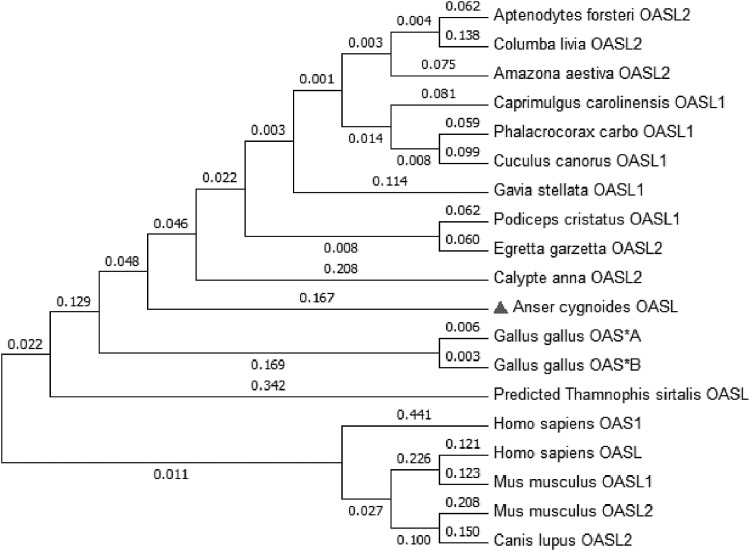

Tissue distribution profile of goOASL

We analyzed the mRNA expression of goOASL with total RNA extracted from the tissues mentioned above both in healthy adult goose and gosling by using RT-qPCR. It was shown that, the highest levels of goOASL expression were detected in the blood of adult goose and gosling (Fig. 3). The goOASL mRNA had high transcription levels in lung, thymus, pancreas, and spleen in adult goose (Fig. 3A), whereas in gosling, in lung, proventriculus, small intestine, pancreas, thymus, harderian gland, cecum, and cecal tonsil, goOASL had high transcription levels. (Fig. 3B). Low levels of goOASL expression were always found in the heart, liver, muscle, skin of investigated gosling and adult goose.

FIG. 3.

goOASL mRNA transcription levels in healthy adult goose (A) and gosling (B) tissues. The mRNA level of goOASL was quantified by RT-qPCR. GAPDH was used as control gene. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism software and represented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Tissues are brain (B), bursa of Fabricius (BF), blood (BL), cecum (Ce), cecal tonsil (CT), gizzard (Gi), heart (H), harderian gland (HG), kidney (K), liver (Li), lung (Lu), muscle (M), pancreas (P), proventriculus (Pr), small intestine (SI), skin (Sk), spleen (Sp), thymus (T), and trachea (Tr). RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

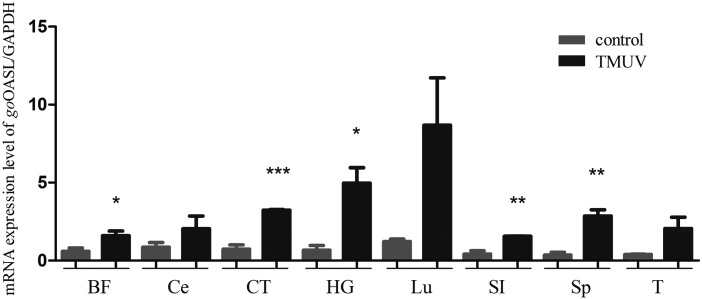

The mRNA transcriptions of goOASL in the immune-associated tissues of DTMUV-infected goslings

In various immune-associated tissues of DTMUV-infected gosling, the mRNA transcriptions of goOASL were upregulated (Fig. 4). The mRNA transcriptions of goOASL in cecum, lung, and thymus were increased, but there were no significant difference with control samples. The goOASL expression in the bursa of Fabricius and harderian gland of DTMUV-infected gosling was significantly different from control groups (0.01<P < 0.05). The goOASL expression in cecal tonsil, small intestine, and spleen had extremely significant difference (P < 0.01) compared with normal groups, which is in line with clinical symptoms and histopathological changes of DTMUV-infected gosling (Ti and others 2015).

FIG. 4.

GoOASL mRNA levels in DTMUV-infected 3-day-old goslings. Tissues of 5 infected goslings and 5 healthy goslings were collected and mRNA levels of goOASL were quantified by RT-qPCR. GAPDH was used as control gene. Data were represented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). The statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Related tissues, including bursa of Fabricius (BF), cecum (Ce), cecal tonsil (CT), harderian gland (HG), lung (Lu), small intestine (SI), spleen (Sp), and thymus (T).

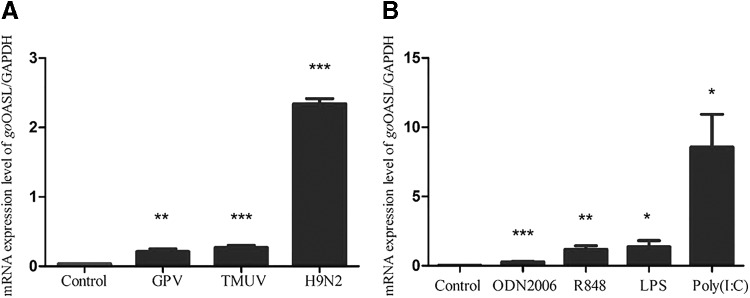

The effects of virus pathogens and agonists on the relative gene expression level of goOASL in PBMCs

In goose PBMCs, after being stimulated by GPV, H9N2 AIV, and DTMUV, goOASL transcription levels were significantly upregulated in all virus-infected groups (P < 0.01) compared with the control group (Fig. 5A). With the stimulus of agonists LPS, ODN2006, Poly (I: C), and R848, the mRNA levels of goOASL in PBMCs were significantly upregulated (0.01<P < 0.05) in LPS- and Poly (I: C)-treated groups, and extremely upregulated (P < 0.01) in ODN2006- and R848-treated groups (Fig. 5B). In vitro study, the PBMCs stimulated with DTMUV, H9N2 AIV, GPV, Poly (I: C), ODN2006, R848, and LPS suggested that all of the stimulators had direct effects on goOASL expression level.

FIG. 5.

GoOASL mRNA expression levels in PBMCs stimulated by virus pathogens (A) and agonists (B). The mRNA levels of goOASL were quantified by RT-qPCR. GAPDH was used as housekeeping gene. Data were represented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). The statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. The cell density was adjusted as 1 × 106/mL, Virus pathogens were GPV (10−6.6 EID50/0.2 mL), H9N2 AIV (7.14 × 1012.64 copies/mL), and DTMUV (6.3 × 10−6 TCID50/mL), with 50 μL to stimulate cells for 6 h, respectively. Agonists, including LPS, R848, Poly (I: C), and ODN2006, the final concentration of stimulus were 25, 5, 30, and 50 μg/mL correspondingly.

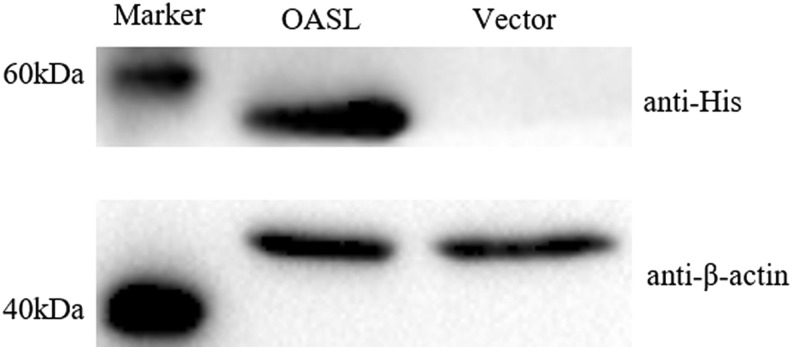

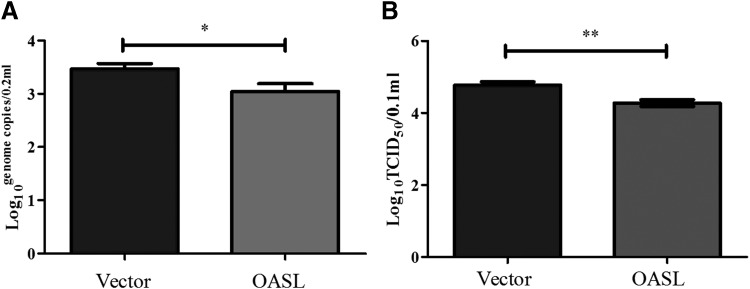

GoOASL plays an antiviral role against NDV infection in GEFs

Western blotting revealed that goOASL was successfully expressed in GEFs transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His expression vector (Fig. 6). Cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His for 36 h, whereas pcDNA3.1(+)-Vector was used as negative control, after which the cells were infected with NDV. Virus genome copies in goOASL overexpression cells were significantly different from control (0.01<P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A). The result suggested that goOASL can inhibit the replication of NDV. Moreover, in virus titer TCID50, extremely significant difference (P < 0.01) was observed between goOASL overexpression cells and control (Fig. 7B), it indicated that virus titer decreased significantly in the presence of goOASL protein. From the results, we can observe a modest antiviral function of goOASL protein against NDV in GEFs.

FIG. 6.

The overexpression of goOASL protein in GFE cells was confirmed by Western blotting analysis. Goose embryo fibroblast cells (GEFs) were transfected with pcDNA3.1(+) plasmids encoding C-terminally His-tag goOASL protein for 36 h, whereas pcDNA3.1(+)-vector served as negative control. Mouse anti-His or anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used as primary antibody. HRP-goat anti-mouse IgG was used as secondary antibody.

FIG. 7.

Antiviral activity of goOASL against Newcastle disease virus in GEFs. Confluent GEFs seeded in 12-well plates were transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His and pcDNA3.1(+)-vector (negative control) for 36 h, then the cells were infected with NDV at 200TCID50/well for 24 h. (A) Viral genome copies were assayed by RT-qPCR. (B) Virus titer 50% tissue culture infective dose/0.1 mL (TCID50/0.1 mL) was determined on GEFs in 96-well plates using the standard method of Karber. Data were represented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). The statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The OAS was first reported in 1974, and it was found in human cells after interferon treatment (Kerr and others 1974). Later, people found OAS in mouse, pig, cattle, and unicellular lower eukaryote (Perelygin and others 2006; Schröder and others 2008). Human OASL was found in 1998 (Hartmann and others 1998; Rebouillat and others 1998), and compared with OAS, OASL has additional 2 UBL repeats. MOASL was found in dendritic cell reported by Tiefenthaler M and his colleagues in 1999 (Tiefenthaler and others 1999). Chicken that carry OASL produce 2 types of OAS and (OAS*A 58 kDa and OAS*B 54 kDa) was reported in 1998 (Yamamoto and others 1998).

In this study, the full length of goOASL cDNA was cloned and sequenced successfully for the first time. In chicken, the OASL protein divided into 2 forms, however, it seems that only one OASL protein was identified in goose. Considering that goose belongs to water fowl, and chicken is fowl, and duck OASL is still unknown, maybe there is only one OASL protein in aquatic birds. The evolutionary tree data demonstrated that goOASL was conservative in avian. The mOASL1 is homologous to huOASL rather than mOASL2, and as is mentioned in the previous article, mOASL2 protein is a functional intermediate between the NTase active and NTase inactive proteins (Eskildsen and others 2003).

The tissue distribution analysis revealed that goOASL mRNA was broadly distributed in most tissues of healthy gosling and adult goose, especially had the highest expression level in blood, which is consistent with the reports that OASL mRNA largely transcribes in blood as described in chicken and human (Hartmann and others 1998; Tatsumi and others 2000). Analyzed mRNA expression levels of OASL in gosling, goOASL exists in all immune-associated tissues, which is similar to mOASL and huOASL (Hartmann and others 1998; Kakuta and others 2002). GoOASL mRNA has high transcription level in blood, there are abundant mononuclear cells and lymphocytes, and maybe goOASL mainly concentrated on mononuclear cells or lymphocytes, or both of them. Moreover, goOASL largely distributes in the digestive tract and digestive gland tissues (cecum, small intestine, proventriculus, and pancreas), as well as in respiratory tract tissues (lung and trachea). In mouse, OASL still has high expression levels in intestine and lung (Kakuta and others 2002). We can come to a conclusion that goOASL, which especially indwells in goose mucosal immune system, has a relatively high mRNA level in gosling. These indicate that goOASL might have an important anti-infection immune function.

The goOASL protein consists of an NTase domain in the N terminal, an OAS domain in the middle, and 2 UBL repeats in the C terminal. NTase domain and OAS domain are essential enzyme activity areas that contain several conserved motifs: P-loop, D-box, LIRL, YALELLT, and RPVILDPADP (Eskildsen and others 2003; Kjaer and others 2009). The P-loop motif involves in the binding of ATP (Kon and Suhadolnik 1996; Hartmann and others 2003; Torralba and others 2008). D-box motif contributes to the binding of Mg2+ ions (Eskildsen and others 2003; Torralba and others 2008; Kjaer and others 2009). LIRL, YALELLT, and RPVILDPADP are special to OAS protein, their sequences are highly conserved. Mutations in these domains can result in reduced activity (Hartmann and others 2003; Martin and Keller 2007; Torralba and others 2008). RPVILDPADP domain may play a role in nucleotide recognition (Torralba and others 2008). Several single amino acids are very important for OAS activity (Bandyopadhyay and others 1998; Sarkar and others 1999; Justesen and others 2000; Eskildsen and others 2003; Hartmann and others 2003; Martin and Keller 2007; Torralba and others 2008), such as amino acids lysine (K) and arginine (R) (highlight in pink color, Fig. 1), which exists not only in NTase domain, but also in OAS domain, and all of them involve in the binding of dsRNA (Kon and Suhadolnik 1996; Hartmann and others 2003; Ibsen and others 2015). In P-loop and D-box, GS and D (highlight in brown color, Fig. 1) are conserved active site residues of NTase family (Sun and others 2013). MOASL1 protein has a deficiency of an amino acid in conserved active site residues in P-loop, which may lead to the loss of enzymatic activity. Moreover, in huOASL and mOASL1, aspartic acids in D-box domain are not conserved (3 aspartic acids are substituted in huOASL, whereas 2 of 3 aspartic acids are substituted in mOASL1). All of those changes are thought to result in the inactivating of NTase (Eskildsen and others 2003). A highly conserved amino acid sequence of goOASL were detected in the P-loop and D-box motifs, which is similar to chicken OAS*A and OAS*B, as well as human OAS1 (huOAS1) and mOASL2, strongly suggesting that goOASL protein must be an NTase active protein.

Consistent with all OASL proteins, goOASL contains 2 UBL repeats, which was involved in huOASL-mediated enhancement of RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling (Zhu and others 2015). Collectively, from the predicted gene structure of goOASL, we can suggest that goOASL may inhibit the virus infection by RNase L-dependent signal pathway because of its NTase region, while it also may control the virus infection by RNase L-independent signal pathway (by RIG-dependent signal pathway) because of the interaction between the CARD domain of RIG-I receptor and 2 UBL repeats of OASL.

Previous studies identified that huOASL can inhibit hepatitis C virus (HCV) and EMCV (Marques and others 2008; Ishibashi and others 2010). Mouse OAS can resist EMCV, coxsackievirus B4 and reovirus (Zhou and others 1997; Flodstrom-Tullberg and others 2005; Smith and others 2005). HuOAS1, huOASL, mOASL2, and chicken chOAS*A are associated with the resistance to the WNV (Tag-El-Din-Hassan and others 2012). To further demonstrate whether the goOASL protein has an antiviral activity, we transfected GEFs with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His plasmid, subsequently the cells were infected with NDV. Our data suggested that virus copies were significantly reduced (nearly 12%) in GEFs after transfection with pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His plasmid in contrast to the control. In addition, the samples were collected to compare NDV titer by measured TCID50. TCID50 assay demonstrated that the viral titer in pcDNA3.1(+)-goOASL-His-transfected group was significantly decreased, (nearly 11%) relative to the control group. The results indicted goOASL, one of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in goose, has an antiviral function against NDV in GEFs. The antiviral activity of goOASL was not very strong in the GEFs against NDV as described. The antiviral ability of goOASL protein may be related to the order and the family of viruses, as well as host cells. The goOASL protein may possess a stronger or weaker antiviral activity against other viruses or against NDV in heterologous cells, which deserve further study. Our study focused on the interaction between the goOASL protein and NDV in homogeneous cells, which confirmed the antiviral activity of goOASL protein and provided the useful information for NDV disease treating.

An abundance of researches have demonstrated that OAS family proteins exhibit antiviral effects against various viruses through 2 main pathways, one is RNase L-dependent pathway; through this pathway mOASL2 and mOAS protein can suppress reovirus (Smith and others 2005), while huOAS1 and huOAS3 can resist dengue virus (DENV) (Lin and others 2009). Another is RNase L-independent pathway, huOASL can resist the infection of EMCV requiring the UBL domain (Marques and others 2008), and is inhibitory to HCV replication (Ishibashi and others 2010). The antiviral activity of goOASL against NDV was demonstrated in vitro in GEFs. However, the antiviral mechanism of goOASL protein at the cellular level requires further studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201891), the Innovative Research Team Program in Education Department of Sichuan Province (2013TD0015), the National Science and Technology Support Program (2015BAD12B05), Integration and Demonstration of Key Technologies for Duck Industrial in Sichuan Province (2014NZ0030), and China Agricultural Research System (CARS-43-8).

Author Disclosure Statement

The author declared that no competing financial interests exist regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh A, Sarkar SN, Sen GC. 1998. Production and purification of recombinant 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase and its mutants using the baculovirus system. Biochemistry 37(11):3824–3830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera AK, Kumar M, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. 2002. 2′-5′ Oligoadenylate synthetase plays a critical role in interferon-γ inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection of human epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 277(28):25601–25608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhao QR, Qi YL, Liu F, Wang MS, Jia RY, Zhu DK, Liu MF, Chen XY, Cheng AC. 2015. Immunobiological activity and antiviral regulation efforts of Chinese goose (Anser cygnoides) CD8a during NGVEV and GPV infection. Poultry Sci 94(1):17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar J, Cuevas RA, Goswami R, Zhu JZ, Sarkar SN, Barik S. 2015. 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase-like protein inhibits respiratory syncytial virus replication and is targeted by the viral nonstructural protein 1. J Virol 89(19):10115–10119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen S, Justesen J, Schierup MH, Hartmann R. 2003. Characterization of the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase ubiquitin-like family. Nucleic Acids Res 31(12):3166–3173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flodstrom-Tullberg M, Hultcrantz M, Stotland A, Maday A, Tsai D, Fine C, Williams B, Silverman R, Sarvetnick N. 2005. RNase L and double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase exert complementary roles in islet cell defense during coxsackievirus infection. J Immunol 174(3):1171–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SK, Kusari J, Bandyopadhyay SK, Samanta H, Kumar R, Sen GC. 1991. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of two murine 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetases. J Biol Chem 266(233):15293–15299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann R, Justesen J, Sarkar SN, Sen GC, Yee VC. 2003. Crystal structure of the 2′-Specific and double-Stranded RNA-activated interferon-induced antiviral protein 2′-5′-oligoadenylate Synthetase. Mol Cell 12(5):1173–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann R, Olsen HS, Widder S, Jorgensen R, Justesen J. 1998. p59OASL, A 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase like protein: a novel human gene related to the 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase family. Nucleic Acids Res 26(18):4121–4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanessian AG, Brown RE, Kerr IM. 1977. Synthesis of low molecular weight inhibitor of protein synthesis with enzyme from interferon-treated cells. Nature 268:537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanessian AG, Justesen J. 2007. The human 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase family: unique interferon-inducible enzymes catalyzing 2′-5′ instead of 3′-5′ phosphodiester bond formation. Biochimie 89(6):779–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibsen MS, Gad HH, Andersen LL, Hornung V, Julkunen I, Sarkar SN, Hartmann R. 2015. Structural and functional analysis reveals that human OASL binds dsRNA to enhance RIG-I signaling. Nucleic Acids Res 43(10):5236–5248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi M, Wakita T, Esumi M. 2010. 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase-like gene highly induced by hepatitis C virus infection in human liver is inhibitory to viral replication in vitro. Biochem Bioph Res Co 392(3):397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justesen J, Hartmann R, Kjeldgaard N. 2000. Gene structure and function of the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family. Cell Mol Life Sci 57(11):1593–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta S, Shibata S, Iwakura Y. 2002. Genomic structure of the mouse 2′, 5′-oligoadenylate synthetase gene family. J Interf Cytok Res 22(9):981–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YF, Feng MS, Zhao XQ, Dai X, Xiang B, Gao P, Li YL, Li YL, Ren T. 2016. Newcastle disease virus infection in chicken embryonic fibroblasts but not duck embryonic fibroblasts is associated with elevated host innate immune response. Virol J 13:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr IM, Brown RE. 1978. pppA2′ p5′ A2′ p5′ A: an inibitor of protein synthesis synthesized with an enzyme fraction from interferon-treated cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75(1):256–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr IM, Brown RE, Ball LA. 1974. Increased sensitivity of cell-free protein synthesis to double-stranded RNA after interferon treatment. Nature 250:57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer KH, Poulsen JB, Reintamm T, Saby E, Martensen PM, Kelve M, Justesen J. 2009. Evolution of the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family in eukaryotes and bacteria. J Mol Evol 69(6):612–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon N, Suhadolnik RJ. 1996. Identification of the ATP binding domain of recombinant human 40-kDa 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase by photoaffinity labeling with 8-azido-[a-32P] ATP. J Biol Chem 271(33):19983–19990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin RJ, Yu HP, Chang BL, Tang WC, Liao CL, Lin YL. 2009. Distinct antiviral roles for human 2′, 5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family members against dengue virus infection. J Immunol 183(12):8035–8043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques J, Anwar J, Eskildsen-Larsen S, Rebouillat D, Paludan SR, Sen G, Williams BR, Hartmann R. 2008. The p59 oligoadenylate synthetase-like protein possesses antiviral activity that requires the C-terminal ubiquitin-like domain. J Gen Virol 89(11):2767–2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Keller W. 2007. RNA-specific ribonucleotidyl transferases. RNA 13(11):1834–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelygin AA, Zharkikh AA, Scherbik SV, Brinton MA. 2006. The mammalian 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase gene family: evidence for concerted evolution of paralogous OAS1 genes in rodentia and artiodactyla. J Mol Evol 63(4):562–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A, Sousa CR. 2007. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity 27(3):370–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebouillat D, Marie I, Hovanessian AG. 1998. Molecular cloning and characterization of two related and interferon-induced 56-kDa and 30-kDa proteins highly similar to 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase. Eur J Biochem 257(2):319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar SN, Ghosh A, Wang HW, Sung SS, Sen GC. 1999. The nature of the catalytic domain of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetases. J Biol Chem 274(36):25535–25542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins JW, Rice CM. 2011. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol 1(6):519–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder HC, Natalio F, Wiens M, Tahir MN, Shukoor MI, Tremel W, Belikov SI, Krasko A, Müller WEG. 2008. The 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase in the lowest metazoa: isolation, cloning, expression and functional activity in the sponge Lubomirskia baicalensis. Mol Immunol 45(4):945–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RH, Cirino NM. 1997. RNA decay by the interferon regulated 2-5A system as a host defense against viruses. Modern Cell Biol 17:295–310 [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Schmechel SC, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schiff LA. 2005. Involvement of the interferon-regulated antiviral proteins PKR and RNase L in reovirus-induced shutoff of cellular translation. J Virol 79(4):2240–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun LJ, Wu JX, Du FH, Chen X, Chen ZJJ. 2013. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339(6121):786–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tag-El-Din-Hassan HT, Sasaki N, Moritoh K, Torigoe D, Maeda A, Agui T. 2012. The chicken 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase A inhibits the replication of West Nile Virus. Jpn J Vet Res 60(2–3):95–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi R, Hamada K, Sekiya S, Wakamatsu M, Namikawa T, Mizutani M, Sokawa Y. 2000. 2′, 5′-oligoadenylate synthetase gene in chicken: gene structure, distribution of alleles and their expression. B B A-Gene Struct Expr 1494(3):263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi R, Sekiya S, Nakanishi R, Mizutani M, Kojima S-I, Sokawa Y. 2003. Function of ubiquitin-like domain of chicken 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase in conformational stability. J Interf Cytok Res 23(11):667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ti JF, Zhang L, Li ZJ, Zhao DD, Zhang Y, Li F, Diao YX. 2015. Effect of age and inoculation route on the infection of duck Tembusu virus in goslings. Vet Microbiol 181(3–4):190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiefenthaler M, Marksteiner R, Neyer S, Koch F, Hofer S, Schuler G, Nussenzweig M, Schneider R, Heufler C. 1999. M1204, a novel 2′, 5′-oligoadenylate synthetase with an ubiquitin-like extension, is induced during maturation of murine dendritic cells. J Immunol 163(2):760–765 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torralba S, Sojat J, Hartmann R. 2008. 2′, 5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase shares active site architecture with the archaeal CCA-adding enzyme. Cell Mol Life Sci 65(16):2613–2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AQ, Liu F, Chen S, Wang MS, Jia RY, Zhu DK, Liu MF, Sun KF, Wu Y, Chen XY. 2015. Transcriptome analysis and identification of differentially expressed transcripts of immune-related genes in spleen of gosling and adult goose. Int J Mol Sci 16(9):22904–22926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Liu JX, Chen PC, Jiang YP, Ding LL, Lin Y, Li QM, He XJ, Chen QS, Chen HL. 2014. The sequential tissue distribution of duck Tembusu virus in adult ducks. Biomed Res Int 2014:703930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Iwata A, Koh Y, Kawai S, Murayama S, Hamada K, Maekawa S, Ueda S, Sokawa Y. 1998. Two types of chicken 2′ 5′-oligoadenylate synthetase mRNA derived from alleles at a single locus. B B A-Gene Struct Expr 1395(2):181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou AM, Paranjape J, Brown TL, Nie HQ, Naik S, Dong BH, Chang AS, Trapp B, Fairchild R, Colmenares C. 1997. Interferon action and apoptosis are defective in mice devoid of 2′, 5′-oligoadenylate-dependent RNase L. Embo J 16(21):6355–6363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JZ, Ghosh A, Sarkar SN. 2015. OASL-a new player in controlling antiviral innate immunity. Curr Opin Virol 12:15–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu KS, Huang J, Jia RY, Zhang B, Wang MS, Zhu DK, Chen S, Liu MF, Yin ZQ, Cheng AC. 2015. Identification and molecular characterization of a novel duck Tembusu virus isolate from Southwest China. Arch Virol 160(11):2781–2790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]