Abstract

This pilot study used a randomized controlled trial design to examine the feasibility and explore initial outcomes of a twice weekly, 8-session Child Directed Interaction Training (CDIT) program for children living in kinship care. Participants included 14 grandmothers and great-grandmothers with their 2- to 7-year-old children randomized either to CDIT or a waitlist control condition. Training was delivered at a local, community library with high fidelity to the training protocol. There was no attrition in either condition. After training, kinship caregivers in the CDIT condition demonstrated more positive relationships with their children during behavioral observation. The caregivers in the CDIT condition also reported clinically and statistically significant decreases in parenting stress and caregiver depression, as well as fewer externalizing child behavior problems than waitlist controls. Parent daily report measures indicated significant changes in disciplining that included greater use of limit-setting and less use of critical verbal force. Results appeared stable at 3-month follow-up. Changes in child internalizing behaviors and caregiver use of non-critical verbal force were not seen until 3-month follow-up. Results of this pilot study suggest both the feasibility of conducting full scale randomized clinical trials of CDIT in the community and the promise of this approach for providing effective parent training for kinship caregivers.

Keywords: foster parent training, kinship caregivers, child behavior problems, parenting stress, grandmothers

Over 2.5 million children, approximately 3% of the child population of the United States, live in out-of-home kinship placements (National Kids Count, 2013). Of these, only 100,000 are formal placements, such as those arranged through the Child Welfare System (CWS; National Kids Count, 2014). The remaining placements are informal kinship placements, which consist of guardianship arrangements made through family court or informal family agreements outside the CWS, typically with grandparent caregivers (Cuddeback, 2004).

The most commonly stated reasons for children to enter kinship placements are: parental substance abuse or addiction and parental neglect, abuse, or abandonment (Gleeson et al., 2009). Most children living in these placements have been exposed to traumatic events in early childhood that place them at-risk for emotional dysregulation and disorganized attachment behaviors (Dozier et al., 2006; Howe & Fearnley, 2003). Although children in kinship placements have better mental health outcomes than children in traditional foster placements (Tarren-Sweeney, 2008), their mental health and attachment difficulties are significantly greater than same-age peers outside the CWS (Tarren-Sweeney, 2008). To recover from the effects of trauma, children in kinship care require the same kinds of emotionally-responsive caregiving as other children in the CWS to re-establish the capacity for self-regulation (Dozier, Higley, Albus, & Nutter, 2002) and improve their attachment security, anxiety, and behavior problems (Tarren-Sweeney, 2008).

Kinship caregivers face unique and stressful challenges that affect their parenting. They experience greater depression, less social support, less education, and poorer health than traditional foster parents (Harden, Clyman, Kriebel, & Lyons, 2004). The majority of kinship caregivers are African American, over 50 years of age, with incomes 200% below the federal poverty line (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012). They tend to have lower emotional availability (Harden et al., 2004) and to use more physical discipline than other foster caregivers (Dolan, Casanueva, Smith, & Bradley, 2009). High levels of stress related to caregiving leads to their more negative disciplining patterns and exacerbate child behavior problems (Kelley, Whitley, & Campos, 2011).

Parenting interventions designed specifically for young children and caregivers in kinship care are needed. Parenting interventions designed specifically for kinship caregivers and their children have not been investigated; most intervention studies include kinship and non-kinship caregivers in the same sample (Chamberlain et al., 2008; Timmer, Sedlar, & Urquiza, 2004). Interventions adapted to meet the unique characteristics of the kinship caregiver population should include adaptations for caregivers that demonstrate high levels of parenting stress and for their children that demonstrate less severe child behavior problems than those in traditional foster families (Harden et al., 2004; Tarren-Sweeney, 2008). Research on interventions for these caregivers consists primarily of preliminary studies addressing risk factors for this population including caregiver physical health and social support (Kelley et al., 2011; Strozier et al., 2005; Strozier, 2012), but not parenting stress.

Parent training is known to improve foster caregiver stress, reducing their reactivity to child behavior problems (Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008). However, the availability of parent training support is limited for kinship foster caregivers. They typically do not receive training equivalent to traditional foster parents (Grimm, 2003), and the training provided to foster parents in general often lacks instruction on managing disruptive child behavior (Chamberlain et al., 2008; Denby, Rindfleisch, & Bean 1999). Effective kinship foster parent training in relationship-building skills as well as behavior management would be expected to strengthen placement stability by reducing parenting stress as well as improving child mental health outcomes. Yet there is a dearth of information available on evidence-based treatments for kinship foster caregivers and their children.

Child Directed Interaction Training

A promising intervention for addressing both the mental health needs of young children in kinship care and the parenting needs of their caregivers is Child Directed Interaction Training (CDIT). CDIT is the first phase of Parent Child Interaction Therapy (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011), an evidenced-based treatment for preschoolers with histories of child abuse and neglect (Chadwick Center on Children and Families, 2004; Chaffin & Friedrich, 2004). CDIT focuses on enhancing the caregiver-child attachment relationship by providing caregivers with concrete skills to increase the emotional reciprocity in the caregiver-child interactions while using differential social attention (DSA) to manage child behavior (Harwood & Eyberg, 2006; Herschell & McNeil, 2005). DSA is a paradigm of attending to positive behavior (e.g., playing gently and sharing) and ignoring negative child behavior (e.g., throwing temper tantrums or screaming to get attention) to help children quickly learn a new approach to seeking caregivers attention that is positive and cooperative. Providing CDIT as a stand-along intervention would also be relatively brief. The average number of CDI sessions required to meet mastery is around 6 sessions (Harwood & Eyberg, 2004).

The second phase of PCIT, the Parent Directed Interaction (PDI) includes a specific discipline procedure parents are taught for managing more severely defiant behaviors (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). The PDI is a powerful intervention that may be unnecessary for most kinship families given that (a) most children in kinship foster care have less severe behavior problems than other foster children (Tarren-Sweeney, 2008), and (b) CDIT can reduce behavior problems to below clinical cut-off for almost half of children who present with a clinically significant behavior disorders (Eisenstadt et al., 1999; Harwood & Eyberg, 2006).

Most studies of PCIT with children with histories of maltreatment have focused on biological parents (Chaffin et al., 2004; Chaffin, Funderburk, Bard,Valle, & Gurwitch, 2011) or traditional foster caregivers (McNeil, Herschell, Gurwitch, & Clemens-Mowrer, 2005; Mersky, Topitzes, Grant-Savela, Brondino, & McNeil, 2014; Mersky, Topitzes, Janczewski, & McNeil, 2015) using full-protocol PCIT. A randomized trial of PCIT as a foster parent training model for non-kinship foster parents caring for children with externalizing behavior problems in the clinical range demonstrated improvement in both child externalizing and internalizing child symptoms (Mersky et al., 2014) as well as caregiver parenting stress (Mersky et al., 2015). However, kinship caregivers were intentionally excluded from these studies. A parent training model using CDIT specifically designed for the less severely behavior disordered children in kinship care and their caregivers has not been studied.

This study used a randomized controlled trial design to compare CDIT to a wait-list condition. Pilot studies with such a design provide an efficient method for assessing the applicability of an evidenced-based intervention to a unique community sample (Bowen et al., 2009). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and explore the efficacy of CDIT for kinship caregiver-child dyads. To evaluate the feasibility of CDIT we examined retention rates, therapist fidelity to the model, and caregiver proficiency in positive parenting skills. We hypothesized that caregivers would evidence improved parenting by demonstrating significant increases in positive following skills and significant decreases in negative leading behaviors during observed interactions with their child. We further hypothesized that these changes in caregiver parenting, would be reflected in improved scores on measures of caregiver-child emotional reciprocity, child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, parenting stress and depression, and daily caregiver discipline. We examined these secondary outcomes both immediately after the intervention and at 3-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

Participants were 14 kinship caregivers, 7 in each condition, and the 2- to 7-year-old child whom they described as presenting behavior problems difficult for them to manage. Caregivers were referred to the study over the course of two years by a neighborhood resource center (21%), recruitment flyers (21%), health professionals (29%), or mental health professionals (29%).

Kinship caregivers were eligible for this study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) cared for a child between the ages of 2 and 7; (b) expected the child to reside in their home for the duration of the study; and (c) had a caregiver rating one standard deviation above the normative mean on the Problem Scale of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999). Child exclusion criteria were major visual or auditory impairment or suspected diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Sixty-six families contacted the investigators and completed a telephone screening to determine study eligibility. Of these, 35 caregivers were ineligible due to not being a kinship caregiver, not having a high enough score on the problem scale, or not wanting parent management training but rather seeking services such as tutoring for their child or respite care. These families were given referral information for services more suited to their needs.

Children in this study were 50% female with a mean age of 5.2 years (range = 2.0–7.5 years). Child racial/ethnic distribution was 64% Caucasian, (n = 9), 22% African American (n = 3), 7% Hispanic (n = 1), and 7% biracial (n = 1). Twelve of the 14 children were above the clinical cut-off on disruptive behavior according to the ECBI Intensity Scale (M = 156.6; SD = 6.28; range = 122–202).

Caregivers were grandmothers (86%, n = 12) and great-grandmothers (14%, n = 2), with a mean age of 56.5 years (range = 45.9–73.0 years). Based on caregiver report, one (7%) had less than a high school education, one (7%) completed high school, five (36%) completed some college, five (36%) completed college, and two (14%) held a graduate degree. The mean annual family income was $40,304 (range = $11,000–$80,000; median = $35,000). Four families (29%) lived below the poverty line.

The mean length of child placement in the caregiver’s home was 3.01 years (range = 3 months–7.5 years). Two children (14%) had been adopted, four (29%) were in permanent guardianship, seven (43%) were in temporary guardianship, and two (14%) had informal guardianship arrangements made outside of court or CWS involvement. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control conditions on any demographic variable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Child Directed Interaction Training and Wait-List Conditions

| Characteristic | CDIT | WLC | t(9) | χ2(1) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Child age (months) | 65.14 | 14.11 | 59.29 | 24.57 | 0.55 | – | 0.60 |

| Child gender (% female) | 57.14 | – | 42.85 | – | – | 0.29 | 0.59 |

| Child ethnicity (% minority) | 42.85 | – | 29.00 | – | – | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| Time in caregiver’s home (months) | 25.71 | 24.64 | 45.57 | 27.60 | 1.49 | – | 0.16 |

| Caregiver age (months) | 669.26 | 111.35 | 688.14 | 101.51 | 0.33 | – | 0.75 |

| Family income (in dollars) | 40780 | 31532 | 39899 | 19093 | 0.06 | – | 0.95 |

| Marital status (% married) | 42.85 | – | 71.00 | – | – | 1.17 | 0.28 |

| Caregiver education (% college or greater) | 57.14 | – | 42.85 | – | – | 0.29 | 0.59 |

Note. CDIT = Child Directed Interaction Training condition; WLC = Wait-list Control condition. n = 14

Measures

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory

The ECBI (Eyberg & Pincus, 1999) is a 36-item caregiver-report measure of disruptive behaviors in children aged 2–16. It measures disruptive behaviors in terms of their frequency (Intensity Scale) and the degree to which these behaviors are seen as problematic for the caregiver (Problem Scale). The Problem Scale was used in this study as an inclusion criterion measure. The Intensity Scale was administered at every training session to monitor child progress (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). Within a community sample, the Problem Scale and Intensity Scale have 12-week test-retest reliabilities of .85 and .80, and 10-month test-retest reliabilities of .75 and .75, respectively (Funderburk, Eyberg, Rich, & Behar, 2003). Internal consistency was .82 for the Intensity Scale and .72 for the Problem Scale in this study.

Child Behavior Checklist

One of the two forms of the CBCL (CBCL 1.5–5 years, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; CBCL 6–18 years, Achenbach, & Rescorla, 2000) was administered to the caregivers. The CBCL is a parent-report scale designed to assess children’s behavioral and emotional symptoms during the past 2 months (1.5–5 years) or 6 months (6–18 years). Children’s symptoms are rated on a 100-item (1.5–5 years) or 113-item (6–18 years), 3-point Likert-type scale. Each form of the CBCL contains an externalizing factor scale with 1-week test-retest reliability of .90 (1.5–5 years) or .92 (6–18 years), and an internalizing factor scale with 1-week test-retest reliability of .87 (1.5–5 years) or .91 (6–18 years) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000; 2001). Internal consistency estimates for this study were .85 for the both versions of the internalizing scale. Internal consistency estimates were .40 (1.5–5 years) and .90 (6–18 years) for the externalizing scales.

Child–Parent Relationship Scale

The CPRS (Pianta, 1992) is a 30-item parent-report questionnaire that assesses parents’ perceptions of emotional reciprocity in their relationship with the child. The Positive Aspects of the Relationship (PAR) subscale measures the overall security in the relationship by assessing the parent’s positive feelings toward and interactions with the child (e.g., “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with my child,” “My child openly shares feelings with me”). Parents rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Reliability of the PAR subscale was .72 in the standardization study (Pianta, 1992). Internal consistency for the PAR subscale in the current study was .82.

Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System: Fourth Edition

The DPICS-IV (Eyberg, Nelson, Ginn, Bhuyani, & Boggs, 2013) is an observational coding system of parent-child interactions in standard situations. For this study, observational coding was completed in-room rather than through a bug-in-the-ear device due to the absence of an observation room. The child-led play situation was used to measure parent CDIT skill acquisition. The convergent and discriminative validities of the DPICS categories have been well established and are documented in the DPICS manual (Eyberg et al., 2013). Two DPICS-IV composite categories were used to assess training skills acquisition: (a) Positive Following, the sum of Behavior Descriptions, Reflections, and Labeled and Unlabeled Praises; and (b) Negative Leading, the sum of Criticisms, Questions, and Commands. Inter-coder reliability was calculated using both percent agreement and Kappa. The overall Kappa reliability was .83 and ranged from .50 to 1.00 for the individual categories. Total percent agreement was .90 and ranged from .86 to 1.00 for the individual categories coded in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inter-coder Reliability of the Behavioral Observation Measures

| DPICS Category | Percent Agreement | Kappa |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Following in CLP | ||

| Behavior Description | 81 | .50 |

| Unlabeled Praise | 85 | .75 |

| Labeled Praise | 100 | 1.00 |

| Reflective Statement | 100 | 1.00 |

| Negative Leading in CLP | ||

| Indirect Command | 89 | .86 |

| Direct Command | 98 | .84 |

| Descriptive/Reflective Question | 94 | .83 |

| Information Question | 83 | .82 |

| Criticism | 86 | .78 |

| Total | 90 | .83 |

Note. DPICS = Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System; CLP = Child-Led Play. Percent agreement calculated by summing agreements across participants (and assessment points) and dividing by agreements plus disagreements across participants.

Parent Daily Report and Daily Discipline Inventory

The PDR (Chamberlain & Reid 1987) is a 20-item questionnaire administered to parents by telephone for 5 consecutive days to obtain information on the daily frequency of child disruptive behaviors. The PDR has been found to have test-retest reliability of .62 to .82 (Chamberlain & Reid, 1987). Scores on this instrument were not used in this study; it was administered to permit administration of the DDI (Webster-Stratton & Spitzer, 1991), a companion measure of parent responses to the negative child behaviors reported on the PDR.

An adapted version of the DDI was used to assess change in discipline practices. The three composite discipline categories used in this study were: (a) Percent Critical Verbal Force (CVF) - verbal criticism or intimidation of the child; (b) Percent Non-Critical Verbal Force (NCVF) - commands or repeated commands; (c) Percent Limit Setting - time-out, removal of privileges, or natural consequences. Percentages in these categories were calculated by dividing the frequency of occurrence of the category by the total sum of disciplinary responses. Scores on the original DDI demonstrated inter-rater reliability of .94 for Critical Verbal Force, and .97 for Limit Setting (Webster-Stratton & Spitzer, 1991). Non-Critical Verbal Force was a new category added to the DDI. In the current study, percent agreement was .76 for Critical Verbal Force, .66 for Non-Critical Verbal Force, and .91 for Limit Setting.

Beck Depression Inventory-II

The BDI-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire assessing depression in adults. This measure provides a 4-choice response option on a scale ranging from 0 to 3. Total scores range from 0 to 63 and indicate the severity of depression (0–13 minimal, 14–19 mild, 20–28 moderate, 29–63 severe). Internal consistency estimates in the standardization sample were .91, and test–retest reliability was .93. In this study, internal consistency was .91.

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form

The PSI-SF (Abidin, 1995) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire of parenting stress consisting of 3 subscales measuring parent distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child behavior. The total score of the PSI-SF was used in this study. Internal consistency in the standardization sample was .91, and test-retest reliability was .84. Internal consistency in the current study was .83.

Procedures

Initial Telephone Screening

Initial screening was conducted during the first telephone contact with interested participants. As recommended by Dennis and Neese (2000) for increasing study participation from diverse populations, culturally sensitive and easy-to-understand terms were used (such as “classes” and “trainer” rather than “treatment” or “therapist”) when describing the study. The mutual benefits of the research to both participant and researcher were also explained (Dennis & Neese, 2000). After describing the study, a brief questionnaire on study eligibility and the ECBI Problem Scale were administered to the caregiver. Families meeting study criteria were scheduled for a Time 1 assessment at the Library Partnership, a neighborhood resource center for low-income and at-risk families.

Kinship caregivers brought official documentation to confirm they were qualified to provide consent on behalf of the child to participate in this research study. In three cases where the kinship caregiver did not have this documentation, consent for the child’s participation was obtained from the biological parents of the child.

Assessment Procedures

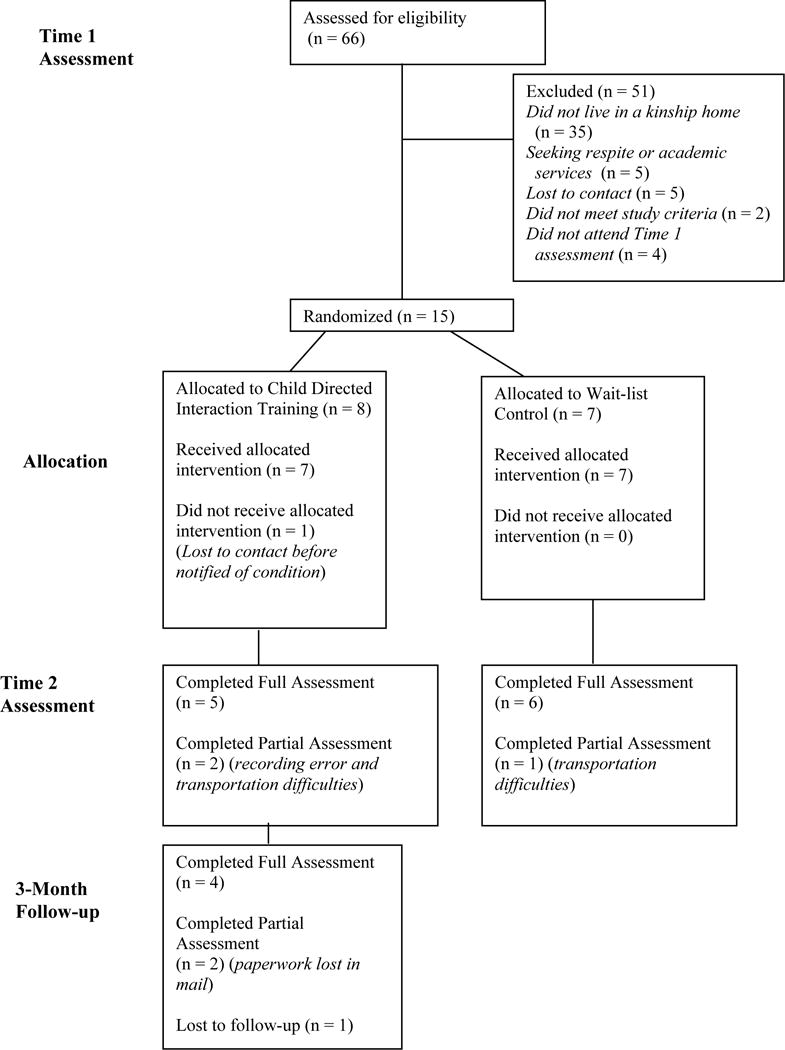

The Time 1 assessment consisted of review of Institutional Review Board informed consent and administration of questionnaires. Two video-recorded standard DPICS-IV observations of the child-led play situation were completed, once before and once after administration of questionnaires. The PDR/DDI was administered by telephone for 5 evenings within 7 days following the Time 1 assessment. After completion of the Time 1 assessment, the 15 participants were randomly assigned to the CDIT condition (n = 8) or the WLC condition (n = 7). One family assigned to the CDIT condition was lost to contact before being notified of their training condition.

The Time 2 assessment occurred after CDIT training completion for the CDIT condition and immediately before treatment began for the WLC condition, approximately 7 weeks following the Time 1 assessment. Behavioral observations, questionnaires, and parent daily reports were repeated. All participants received $10 for the completion of this assessment.

The Time 3 assessment occurred 3 months following the Time 2 assessment for families in the CDIT condition. At the Time 3 follow-up assessment, the questionnaires were completed by mail, and parent daily report telephone calls were completed. The CDIT condition received $15 for completion of the follow-up assessment. The wait-list control (WLC) condition was paid $15 for completion of their post-treatment assessment in order to provide equal compensation for both conditions. (See Figure 1 for participant flow chart).

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants through Each Stage of the Experiment

Training Procedures

All CDIT sessions were conducted by four advanced graduate student trainers who had completed a graduate level course and seen at least two cases to completion in PCIT. To help assure fidelity to the training protocol, trainers completed Treatment Integrity Checklists (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011) during each session. Overall fidelity to the protocol was 96%. Trainers met weekly with the first author for case supervision to monitor progress.

During training delivery, several considerations were given to cultural factors common to the kinship caregiver population. Although the standard PCIT protocol is performance-based, a twice-weekly, 8-session schedule was chosen, providing concrete start and end dates for the training within a one-month time frame, to ease scheduling burdens for kinship caregivers. The limit of 8 sessions, which is 2 more than found necessary to meet CDI mastery criteria in most PCIT studies (e.g., Harwood & Eyberg, 2006) was selected to help assure adequate dosage of CDIT.

Trainers telephoned the caregivers before each session to remind them of the session or to reschedule for another time. This strategy has frequently been used to retain at-risk families in treatment (e.g., Bagner, Rodriquez, Blake, & Rosa-Olivares, 2013).

The training sessions were held in a neighborhood resource center to provide a more convenient and less intimidating setting for the families than the research hospital. Access to observational facilities or technical equipment for coaching was not available; therefore, in-room coaching of PCIT was conducted and is a coaching adaptation that has been found successful (Briegel, Walter, Schimek, Knapp, & Bussing, 2015). A second advantage of holding the sessions in the resource center was the availability of a full-time social worker who was able to meet emergent family needs identified during the training period, such as clothing, holiday gifts, and monetary assistance.

The CDIT sessions followed the standard PCIT protocol (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). In the first session, caregivers were taught to use relationship enhancing Positive Following skills and to avoid intrusive Negative Leading behaviors, in a differential attention paradigm. The 7 subsequent CDIT sessions were coaching sessions, in which caregivers practiced the new skills with their child while being coached by the trainer. The first three coaching sessions focused solely on coaching the CDIT skills. The last 4 sessions were supplemented with tailored discussions around the PCIT caregiver handouts on creating labeled praises, modeling, kids and stress, and getting support for children and caregivers (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011).

Results

Feasibility of CDIT

Training attrition was 0%. One participant from the CDIT condition was lost to 3- month follow-up. Five of the seven caregivers, 71%, attained CDIT mastery criteria for the Positive Following skills and four of seven caregivers, 57%, met mastery criteria for the Negative Leading behaviors. Average daily homework completion rate was 62% with a range of 33% to 93%. Trainers completed training integrity checklists following each CDIT session, obtaining 96% accuracy with the treatment manual (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). At the completion of CDIT, three families indicated a desire for additional services and were provided referrals for further intervention, including trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (n = 1) or full-protocol PCIT (n = 2).

Efficacy of CDIT

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), with Time 1 scores as the covariate, were used to determine treatment effects. ANCOVA is recommended for randomized controlled trials because it corrects for shared variance and is therefore a more statistically powerful method than a repeated measures analysis of variance (Rausch, Maxwell, & Kelley, 2003). Differences between conditions at Time 2 were examined for all variables. No outliers were present; all data fell within three standard deviations of the mean. Homogeneity of variance assumptions were met on all variables according to Lavene’s Test for the Equality of Variances. For all analyses, alpha level was set at .05, and Cohen’s d was used to measure effect sizes. Effect sizes greater than 0.80 were considered a large effect.

Caregiver Report of Child Behavior

Caregivers in the CDIT condition reported significantly fewer child externalizing behavior problems than the WLC condition, F(1,11) = 5.94, p = .03, Cohen’s d = 1.04, with large effects. Differences between the CDIT and WLC conditions were not detected in caregiver report of child internalizing symptoms, F(1,11) = 0.00, p = .97, Cohen’s d = 0.22. (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for the Child Directed Interaction Training and Wait-List Control Conditions

| Measure | Condition | Time 1 | Time 2 | F (1,11) | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| CBCL-E | CDIT | 67.57 | 4.08 | 56.71 | 8.75 | |||

| WLC | 69.29 | 10.00 | 66.43 | 9.89 | 5.94 | .03 | 1.04 | |

| CBCL-I | CDIT | 59.43 | 12.79 | 53.29 | 6.78 | |||

| WLC | 63.29 | 8.76 | 55.57 | 13.29 | 0.00 | .97 | 0.22 | |

| CPRS PAR | CDIT | 42.14 | 5.79 | 45.71 | 3.99 | |||

| WLC | 38.57 | 6.63 | 40.14 | 4.95 | 4.80 | .05 | 1.24 | |

| PSI-SF total | CDIT | 92.71 | 14.73 | 67.00 | 16.22 | |||

| WLC | 96.00 | 24.08 | 95.71 | 21.34 | 12.59 | .005 | 1.51 | |

| BDI-II total | CDIT | 10.29 | 3.36 | 5.00 | 6.68 | |||

| WLC | 11.06 | 5.09 | 11.14 | 8.92 | 6.97 | .02 | 0.78 | |

| DDI CVF (%) | CDIT | 29.17 | 17.008 | 9.12 | 10.11 | |||

| WLC | 30.14 | 13.85 | 23.86 | 8.03 | 6.31 | .03 | 1.61 | |

| DDI NCVF (%) | CDIT | 16.31 | 7.63 | 17.50 | 9.31 | |||

| WLC | 13.43 | 6.13 | 23.00 | 6.98 | 1.77 | .21 | 0.69 | |

| DDI LS (%) | CDIT | 28.94 | 12.82 | 52.23 | 14.33 | |||

| WLC | 29.00 | 9.71 | 30.29 | 20.06 | 4.87 | .05 | 1.26 | |

Note. CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist-externalizing scale; CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist-internalizing scale; CPRS PAR = Child Parent Relationship Scale Positive Aspects of the Relationship; PSI-SF = Parenting Stress Index- Short Form; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; DDI CVF = Daily Discipline Inventory Critical Verbal Force; DDI NCVF = Daily Discipline Inventory Non-Critical Verbal Force; DDI LS = Daily Discipline Inventory Limit Setting; CDIT = Child Directed Interaction Training condition; WLC = Wait-List Control condition.

Caregiver Report of Relationship Quality

Caregivers in the CDIT condition reported significantly more positive interactions with their child than WLC caregivers, F(1,11) = 4.80, p = .05, Cohen’s d = 1.24 The effect size was large. (See Table 3).

Caregiver Self-Report of Parenting Stress and Depression

Caregivers in the CDIT condition reported lower total caregiver stress on the PSI-SF than WLC caregivers, F(1, 11) = 12.59, p = .005, Cohen’s d = 1.51. Caregivers in the CDIT condition also reported fewer depressive symptoms on the BDI-II, F(1, 11) = 6.97, p = .02, Cohen’s d = 0.78. Large and medium effect sizes were detected between conditions for these measures. (See Table 3).

Caregiver Daily Discipline Report

Caregivers in the CDIT condition reported a significantly lower percentage of critical verbal force, F(1,11) = 6.31, p = .03, Cohen’s d = 1.61, and a significantly greater use of limit setting, F(1,11) = 4.87, p = .05, Cohen’s d = 1.26, in their disciplinary response to difficult child behaviors than the WLC caregivers Effect sizes for both limit setting and critical verbal force were large. Between-condition differences in non-critical verbal force were not statistically significant, F(1,11) = 1.77, p = .21, Cohen’s d = .69. Mean scores for the Time 1 and Time 2 assessment for the CDIT condition and the WLC condition are shown in Table 3. One caregiver was unreachable by phone for the Time 2 assessment.

Observed Parenting Skills

Observational data were not obtained for three families at the Time 2 assessment due to lack of transportation (n = 2), and a video recording error (n = 1). Caregivers in the CDIT condition used significantly more Positive Following skills, F(1, 8) = 31.02, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 4.68, and significantly fewer Negative Leading behaviors, F(1, 8) = 26.42, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 2.50, than parents in the waitlist condition. The effect size for differences in observed parenting skills at Time 2 were large. (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Observed Parenting Behaviors

| Measure | Condition | Time 1 | Time 2 | F(1,8) | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| Positive Following | CDIT | 7.92 | 2.18 | 26.56 | 5.64 | |||

| WLC | 3.57 | 1.17 | 4.00 | 3.82 | 31.02 | .001 | 4.68 | |

| Negative Leading | CDIT | 37.50 | 4.84 | 6.30 | 2.77 | |||

| WLC | 46.64 | 11.15 | 48.33 | 23.58 | 26.42 | .001 | 2.50 | |

Note. CDIT = Child Directed Interaction Training condition; WLC = Wait-List Control condition

Clinical Significance

To evaluate clinically significant change in the CDIT and WLC condition, it is necessary to (a) calculate the Reliable Change Index for each participant (Jacobson, Follette, & Revenstorf, 1984), and (b) determine whether the participant’s score is in the clinical range at Time 1 and in the non-clinical range at Time 2. If both (a) and (b) are present, then the change is considered clinically significant (Jacobson, Roberts, Berns, & McGlinchey, 1999). As shown in Table 5, a relatively high percentage of caregivers experienced clinically significant change in their child’s externalizing behavior problems and their own parenting distress after CDIT, whereas a minority of families in the WLC condition experienced clinically significant change.

Table 5.

Reliable Change and Clinically Significant Change in the Child Directed Interaction Training and Wait-List Control Conditions

| Number in Clinical Range | Reliable Changea | Clinically Significant Changeb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Measure | Condition | N | Time 1 | Time 2 | Number | % | Number | % |

| CBCL externalizing | CDIT | 7 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 86 | 5 | 71 |

| WLC | 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 43 | 2 | 29 | |

| BDI-II total score | CDIT | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WLC | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PSI-SF total score | CDIT | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 71 | 5 | 71 |

| WLC | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 29 | |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; PSI-SF = Parenting Stress Index- Short Form.

The Reliable Change Index (RCI) was used to determine whether the magnitude of change exceeded the margin of measurement error. The RCI was calculated by dividing the magnitude of change between the Time 1 and Time 2 scores for each individual by the stand error of the sample difference scores. RCIs greater than 1.96 were statistically significant.

A child was determined to have made a clinically significant change if the child’s score was in the clinically significant range ant Time 1 assessment and in the normal range at Time 2 assessment, and the change in the individual score from Time 1 to time 2 was statistically reliable as defined using the RCI.

Follow-up Analyses

Repeated-measures t tests were conducted to determine if outcomes for the CDIT condition detected at the Time 2 assessment were maintained at 3-month follow-up. No significant differences at follow-up were found for child externalizing problem behaviors, caregiver parenting stress or depression, caregiver-child relationship, caregiver critical verbal force, or caregiver limit setting. Caregiver use of noncritical verbal force and child internalizing behavior problems were significantly improved between the Time 2 and follow-up assessment. Corresponding means, standard deviations, and significance levels are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Maintenance of Training Gains at 3-Month Follow-Up

| Measure | Time 2 | Time 3 | t (4) | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| CBCL-E | 53.00 | 8.68 | 51.50 | 2.38 | 0.44 | .69 | 0.24 |

| CBCL-I | 50.00 | 4.69 | 42.50 | 5.00 | 25.98 | .000 | 1.54 |

| CPRS PAR | 46.25 | 4.50 | 47.00 | 2.83 | −0.35 | .75 | 0.20 |

| PSI-SF Total | 78.00 | 8.29 | 78.25 | 7.04 | −0.04 | .97 | 0.03 |

| BDI-II | 8.02 | 4.01 | 5.75 | 2.87 | −1.12 | .34 | 0.65 |

| DDI CVF (%) | 13.17 | 9.61 | 14.80 | 9.72 | −0.61 | .56 | 0.17 |

| DDI NCVF (%) | 20.90 | 9.43 | 11.90 | 10.10 | 2.62 | .03 | 1.56 |

| DDI LS (%) | 19.67 | 6.22 | 17.80 | 5.63 | −1.20 | .26 | 0.32 |

Note. CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist-externalizing scale; CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist-internalizing scale; CPRS PAR = Child Parent Relationship Scale Positive Aspects of the Relationship; PSI-SF = Parenting Stress Index- Short Form; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; DDI CVF = Daily Discipline Inventory Critical Verbal Force; DDI NCVF = Daily Discipline Inventory Non-Critical Verbal Force; DDI LS = Daily Discipline Inventory Limit Setting.

Discussion

This pilot study provides evidence of the feasibility of CDIT for kinship caregivers. The retention rate for CDIT was notably high, with 100% of families completing the training protocol. These findings compare favorably with other foster parent training programs conducted with both kin and non-kin caregivers (Price at al., 2008). Feasibility was also supported by findings showing moderately high adherence to home practice of parenting skills as well as observed improvement in caregiver parenting. High fidelity to the training protocol was maintained in a community setting.

The high retention rate may have been due to the consideration given to specific cultural factors that are salient in kinship caregiver populations, including barriers associated with low income (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012) and low social support (Harden et al., 2004). To improve treatment attendance, sessions were held twice-weekly, training was time-limited, and reminder phone calls were made the day or morning before each session. To improve social support, sessions were held at a neighborhood resource center staffed by a full-time social worker. Although not all agencies may be able to support the particular resources of the setting in which this training was designed, it is clear that consideration of the specific needs of the kinship caregiver population in tailoring the structure, format, and location of the training contributed to successful retention of the participants.

Due to the small sample size in this pilot study, interpretations of the hypothesized child and caregiver outcomes of CDIT were facilitated by taking into account the effect sizes of the changes (Maxwell, 2004) and by examining the clinical significance of the findings for each family. Preliminary results of this intervention for kinship foster care families suggest that CDIT decreases child externalizing behavior problems, caregiver depressive symptoms, and parenting stress while facilitating positive changes in caregiver discipline strategies and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, all of which were maintained for 3 months following the intervention. These findings were supported by a majority of large effect sizes, emphasizing the importance of replicating this study with a larger sample to evaluate the stability of the results and draw firmer conclusions regarding the efficacy of this brief, community-based intervention.

Improvements detected following CDIT align with recommendations outlined by Kelley et al. (2011), which suggest that interventions for kinship caregivers address both child behavior management and parenting distress. Addressing these two factors in this population is important because children in kinship care are at-risk for exhibiting child behavior problems if high levels of caregiver distress are present (Kelley et al., 2011). CDIT appears to meet the training needs of kinship caregivers and the changes in caregiver distress and child behavior problems were similar to findings following performance-based CDIT (Harwood & Eyberg, 2006). Overall, the direction of change in kinship caregiver parenting skills was positive and facilitated an improvement in the reciprocity of the caregiver-child relationship and more general parenting practices.

Changes in internalizing behavior problems and limit setting were not detected until the 3-month follow-up assessments. It may be that the time period needed to detect changes in these domains exceeds the 4-week length of this brief CDIT protocol. In full protocol, internalizing behaviors are significantly decreased (Chase & Eyberg, 2008), and more effective parenting practices were detected following performance-based CDIT alone (Harwood & Eyberg, 2006). It might also be that improvements in internalizing symptoms and parental limit setting are secondary changes related to increased warmth in the caregiver child relationship. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the stability of these findings.

This study has both limitations and strengths that should be acknowledged. As a pilot study, sample size reduced statistical power, which can increase the likelihood of rejecting a null hypothesis when it is true. Generalizability of the study was also limited by the fact that the sample was less culturally diverse than other studies of kinship caregivers, which indicate a high percentage of minority families (Winokur, Holtan, & Batchelder, 2014), and with higher annual income than kinship caregivers described in previous studies (Berrick, Barth, & Needell, 1994).

The design of this pilot study is a significant strength. Well-conducted group-design studies include prospective study design, clear inclusion/exclusion criteria, an appropriate control condition, random assignment, reliable measures, clearly specified sample characteristics, clearly described statistical procedures, and use of a defined treatment protocol with ways to assess integrity (Brestan & Eyberg, 1998). This study meets these criteria. The 100% retention rate, is also a significant strength. The lack of attrition provides strong support for the feasibility of conducting a larger RCT with CDIT for kinship caregivers.

Replication of this study with a larger and more diverse sample of kinship caregivers will be important. Strong partnerships with formal and informal community leaders, including church leaders and established programs serving low-income families, is essential for increasing sample diversity (Dennis & Neese, 2000). Plans for program sustainability will also be important, both to aid in recruitment and for long-term impact in the community.

Conclusions and Implications

Results from this pilot study are encouraging in suggesting the feasibility of improvements for children in kinship care. Identifying relatively brief and effective interventions for kinship caregivers and the children in their care is crucial for preventing negative psychosocial outcomes within this vulnerable group. Providing CDIT within the community is one promising approach.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the University of Florida College of Public Health and Health Professions Graduate Research Award, the Center for Pediatric Psychology and Family Studies Research Award, and the National Institute of Mental Health RO1MH72780. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Special acknowledgement for this research is extended to the Library Partnership and Partnership for Strong Families where this research was conducted, the dissertation committee members, David Diehl, PhD, Ronald Rozensky, PhD, and Brenda Wiens, PhD., and the families who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Research reported in this publication was based on the dissertations of the first two authors, supervised by the third author, and was conducted in collaboration with the Partnership for Strong Families, Gainesville, Florida.

The data were previously presented at the 2013 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy International Biennial Convention and the 2012 Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Preconference on Social and Family Learning.

Contributor Information

Amanda M. N’zi, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, University of Florida

Monica L. Stevens, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, University of Florida

Sheila M. Eyberg, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, University of Florida

References

- Abidin R. Parenting Stress Index-Manual. 3rd. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA preschool forms & profiles–Child Behavior Checklist for ages 6–18. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual of the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles - Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1.5–5. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Rodriquez GM, Blake CA, Rosa-Olivares J. Home-based preventive parenting intervention for at-risk infants and their families: An open trial. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20:334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berrick JD, Barth RP, Needell B. A comparison of kinship foster homes and foster family homes: Implications for kinship foster care as family preservation. Children and Youth Services Review. 1994;16:33–63. 10.1016%2F0190-7409%2894%2990015-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, Fernandez M. How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Prevention Medicine. 2009;36:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. A Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:180–189. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel W, Walter T, Schimek M, Knapp D, Bussing R. Parent-child interaction therapy: In-room-coaching. Kindheit und Entwicklung. 2015;24:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick Center on Children and Families. Closing the quality chasm in child abuse treatment: Identifying and disseminating best practices. San Diego, CA: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Funderburk B, Bard D, Valle LA, Gurwitch R. A combined motivation and parent–child interaction therapy package reduces child welfare recidivism in a randomized dismantling field trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:84–95. doi: 10.1037/a0021227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Silovsky JF, Funderburk B, Valle LA, Brestan EV, Balachova T, Bonner BL. Parent-child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:500–510. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Friedrich B. Evidence-based treatments in child abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:1097–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve L, Heidemarie L, Landsverk J, Reid J. Prevention of behavior problems of children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chase RM, Eyberg SM. Clinical presentation and treatment outcome for children with comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(2):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddeback GS. Kinship family foster care: A methodological and substantive synthesis of research. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:623–639. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denby R, Rindfleisch N, Bean G. Predictors of foster parents’ satisfaction and intent to continue to foster. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:287–303. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis BP, Neese JB. Recruitment and retention of African American elders into community-based research: Lessons learned. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2000;14:3–11. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(00)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan MM, Casanueva C, Smith KR, Bradley RH. Parenting and the home environment provided by grandmothers of children in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:784–796. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Higley E, Albus K, Nutter A. Intervening with foster infants’ caregivers: Targeting three critical needs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:541–554. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lindhiem O, Gordon MK, Manni M, Sepulveda S, Ackerman J. Developing evidence-based interventions for foster children: An example of a randomized clinical trial with infants and toddlers. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:767–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt TH, Eyberg S, McNeil C, Newcomb K, Funderburk B. Parent-child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: Relative effectiveness of two stages and overall treatment outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:42–51. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Funderburk DW. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol. Gainesville, FL: PCIT International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based treatments for child and adolescent disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:213–235. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Ginn N, Bhuyani N, Boggs SR. Manual for the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System. 4th. Gainesville, FL: PCIT International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Pincus DB. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Intervention effects on foster parent stress: Associations with child cortisol levels. Development and psychopathology. 2008;20(03):1003–1021. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburk BW, Eyberg SM, Rich BA, Behar L. Further psychometric evaluation of the Eyberg and Behavior rating scales for parents and teachers of preschoolers. Early Education and Development. 2003;14:67–81. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1401_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JP, Wesley JM, Ellis R, Seryak C, Talley GW, Robinson J. Becoming involved in raising a relative’s child: reasons, caregiver motivations and pathways to informal kinship care. Child & Family Social Work. 2009;14:300–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00596.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm B. Child & Family services reviews: Part II in a series. Foster parent training: What the CFS reviews do and don’t tell us. Youth Law News: Journal of the National Center for Youth Law. 2003;(2) [Google Scholar]

- Harden B, Clyman R, Kriebel D, Lyons M. Kith and kin care: parental attitudes and resources of foster and relative caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood MD, Eyberg SM. Child-Directed Interaction: Prediction of change in impaired mother-child functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:335–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell A, McNeil C. Theoretical and empirical underpinnings for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with child physical abuse populations. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005;28:142–162. [Google Scholar]

- Howe D, Fearnley S. Disorders of attachment in adopted and fostered children: Recognition and treatment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;8:369–386. doi: 10.1177/1359104503008003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D. Psychotherapy outcome research: Methods for reporting variability and evaluating clinical significance. Behavior Therapy. 1984;15(84):336–352. 80002–7. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Roberts LJ, Berns SB, McGlinchey JB. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: description, application, and alternatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:300–307. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Behavior problems in children raised by grandmothers: The role of caregiver distress, family resources, and the home environment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:2138–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE. The persistence of underpowered studies in psychological research: Causes, consequences, and remedies. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:147–163. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Herschell AD, Gurwitch RH, Clemens-Mowrer L. Training foster parents in parent-child interaction therapy. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005:182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Grant-Savela SD, Brondino MJ, McNeil CB. Adapting parent-child interaction therapy to foster care: Outcomes from a randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014:1–11. doi: 10.1177/1049731514543023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Janczewski CE, McNeil CB. Enhancing foster parent training with parent-child interaction therapy: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2015;6:591–616. doi: 10.1086/684123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Kids Count. Children in kinship care [Data File] 2013 Retrieved from http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#USA/1/0.

- National Kids Count. Children in foster care by placement type [Data file] 2014 Retrieved from http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#USA/1/0.

- Pianta RC. Child Parent Relationship Scale [Word Document] 1992 Retrieved from http://curry.virginia.edu/about/directory/robert-c.-pianta/measures.

- Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid JB, Leve LD, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes if children in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch JR, Maxwell SE, Kelly K. Analytic methods for questions pertaining to a randomized pretest, posttest, follow-up design. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:467–486. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozier AL. The effectiveness of support groups in increasing social support for kinship caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strozier A, McGrew L, Krisman K, Smith A. Kinship care connection: A school-based intervention for kinship caregivers and the children in their care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarren-Sweeney M. The mental health of children in out-of-home-care. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21:345–349. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830321fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF) The Annie E Casey Foundation. Baltimore, MD: 2012. Stepping up for kids: What governments and communities should do to support kinship families. [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, Sedlar G, Urquiza AJ. Challenging children in kin versus nonkin foster care: Perceived costs and benefits to caregivers. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:251–262. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Spitzer A. Development, reliability, and validity of the daily telephone discipline interview. Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Winokur M, Holtan A, Batchelder KE. Kinship care for the safety, permanency, and well-being of children removed from the home for maltreatment: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2014;2:1–292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006546.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]