Abstract

Background

Sarilumab is a human monoclonal antibody directed against the alpha subunit of the interleukin-6 receptor complex. In the MOBILITY phase III randomized controlled trial (RCT), sarilumab + methotrexate (MTX) treatment resulted in clinical improvements at 24 weeks that were maintained at 52 weeks in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who have inadequate response to MTX (MTX-IR). These analyses indicate the effects of sarilumab + MTX versus placebo on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in this RCT.

Methods

Patients (n = 1197) were randomized to receive placebo, sarilumab 150 or 200 mg subcutaneously + MTX every 2 weeks for 52 weeks; after 16 weeks, patients without ≥20 % improvement from baseline in swollen or tender joint counts on two consecutive assessments were offered open-label treatment. PROs included patient global assessment of disease activity (PtGA), pain, health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI), Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F). Changes from baseline at weeks 24 and 52 were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures. Post hoc analyses included percentages of patients reporting improvements equal to or greater than minimal clinically important differences (MCID) and normative values in the FACIT-F and SF-36. Pearson correlation between observed PRO scores and clinical measures of disease activity was tested at week 24.

Results

Both doses of sarilumab + MTX vs placebo + MTX resulted in improvement from baseline by week 24 in PtGA, pain, HAQ-DI, SF-36 and FACIT-F scores (p < 0.0001) that was clinically meaningful, and persisted until week 52. In post hoc analyses, the percentages of patients with improvement equal to or greater than the MCID across all PROs were greater with sarilumab than placebo (p < 0.05), with differences ranging from 11.6 to 26.2 %, as were those reporting equal to or greater than normative scores.

Conclusions

In this RCT in patients with MTX-IR RA, sarilumab + MTX resulted in sustained improvement in PROs that were clinically meaningful, greater than placebo + MTX, and complement the previously reported clinical efficacy and safety of sarilumab.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT01061736. February 2, 2010

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Sarilumab, Patient-reported outcomes, Interleukin-6, Fatigue

Background

The initial focus of most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of new therapeutic agents for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is appropriately directed at reducing the symptoms and signs of disease, demonstrating reduction in the progression of structural damage, and improving physical function and health-related quality-of life (HRQOL). Crucial to the evaluation of a new therapeutic agent is the use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to comprehensively define treatment benefit as recommended by current international consensus [1–3].

This manuscript reports PRO data from the 52-week phase III MOBILITY RCT of sarilumab in combination with methotrexate (MTX) in patients with RA, who have inadequate response to MTX (MTX-IR) (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01061736) [4]. Sarilumab is a human monoclonal antibody directed against the alpha subunit of the interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor complex, which mediates pathways that contribute to joint inflammation and destruction, pain, and fatigue in RA [5, 6]. Clinical improvements including symptomatic, functional, and radiographic outcomes were observed at 24 weeks, as early as 2 weeks in some outcomes, and were maintained over the 52-week study duration; the most common treatment-emergent adverse events included infection, neutropenia, injection site reaction, and increased transaminase [4]. Current analyses evaluated the impact of sarilumab on PROs, and correlation between these and changes in disease activity.

Methods

Study design and population

The trial design and methods have been previously described [4]; in short, patients were randomized to receive subcutaneous placebo or sarilumab 150 mg or 200 mg every 2 weeks (q2w) in combination with MTX. Treatment duration was 52 weeks; on or after 16 weeks, patients without ≥20 % improvement from baseline in swollen or tender joint counts on two consecutive assessments or any other lack of efficacy based on investigator judgment were offered rescue therapy with open-label sarilumab 200 mg q2w. Efficacy was evaluated using three co-primary efficacy endpoints: American College of Rheumatology 20 % improvement (ACR20) response [1] at week 24, physical function at week 16 using the health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) [7], and change from baseline in radiographic progression [8] at week 52.

Inclusion criteria were age 18–75 years; fulfilment of ACR 1987 revised classification criteria for RA [9]; active RA (swollen joint count ≥6, tender joint count ≥8; high sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥0.6 mg/dl) despite stable dosing with MTX for ≥12 weeks; anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) or rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity or presence of one or more documented bone erosions; or disease duration ≥3 months [4].

Patient-reported outcomes

The patient global assessment of disease activity (PtGA), pain visual analog scale (VAS) and health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) were administered as part of the ACR response criteria [1] at baseline, weeks 2 and 4, and every 4 weeks thereafter. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) [10] was administered at baseline, weeks 2, 4, 12, 24, 36, and 52, and medical outcomes Short Form-36 (SF-36) Health Survey version 2 [11] was administered at baseline, and weeks 24 and 52 to evaluate general health status, also described as HRQOL. The FACIT-F includes 13 items rated by patients on a scale of 0–4 summarized as a total score of 0–52, with higher scores indicating less fatigue. The SF-36 evaluates eight domains (physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP, i.e., limitations due to physical health), body pain (BP), general health perceptions (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RF, i.e., role limitations due to emotional health), and mental health (MH)). For each domain, item scores are coded, summed, and transformed on to a scale from 0 (worst possible health state measured by the domain) to 100 (best possible health state). These domains are combined into physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores with normative means (SD) of 50 (10).

Statistical analyses

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population was used in the current analyses. Changes from baseline at weeks 24 and 52 were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) that included treatment, prior biological use, region, visit, and treatment by visit interaction as fixed effects, and baseline score as a covariate; results are expressed as least squares mean (LSM) and standard error. In the MMRM analysis, for patients who required rescue, only data up to the time of rescue were included. Statistical significance was claimed only for those outcomes above the break in hierarchical testing used to control for multiple comparisons previously reported [4]. All other p values were tested without adjustment for multiplicity.

The proportion of patients reporting improvement from baseline at week 24 equal to or greater than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in HAQ-DI scores was determined using thresholds ≥0.22 [12] and ≥0.3 points, with both thresholds prespecified. Post hoc responder analyses were conducted to estimate percentages of patients who reported improvement from baseline equal to or greater than the MCID [12, 13] of 10 mm for PtGA and pain VAS scores [13–15]; 2.5 points for SF-36 PCS and MCS scores, 5 points for individual domains [16]; and 4 points for the FACIT-F [10]. In these responder analyses, patients who discontinued or received rescue medication were considered non-responders. The number-needed-to-treat (NNT) was calculated as the reciprocal of the difference in response rates between active treatment and placebo to obtain the outcome of interest in one patient, assessing the magnitude of the benefit obtained with treatment [17]. To further assess benefit, the proportion of patients who reported normative values in the SF-36 summary and domain scores and the FACIT-F were evaluated at week 24, as were those who reported values equal to or greater than the patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) thresholds in the six SF-36 domains for which it has been estimated (PF, 50; BP, 41; GH, 47; VT, 40; SF, 62.5; and MH, 72) [18]. The percentage of ACR20 responders who reported improvements equal to or greater than the MCID was determined post hoc. Correlation analysis (Pearson r) was performed to determine relationships between individual PROs and clinical measures of disease activity including 28-joint disease activity score using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) at week 24. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, SC, USA).

Results

Demographic and disease characteristics

Baseline characteristics were balanced across treatment groups (Table 1). Duration of RA ranged from 8.6 to 9.5 years and approximately 20 % of patients had previously received biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the intention-to-treat population

| Variable | Placebo + MTX (n = 398) | Sarilumab 150 mg q2w + MTX (n = 400) | Sarilumab 200 mg q2w + MTX (n = 399) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.9 ± 11.2 | 50.1 ± 11.9 | 50.8 ± 11.8 |

| Female (%) | 80.7 | 79.8 | 84.5 |

| Race (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 86.2 | 86.3 | 86.0 |

| Black | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Asian | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Other | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| Region (%) | |||

| Western Europe | 18.6 | 18.8 | 18.8 |

| South America | 38.9 | 38.8 | 38.8 |

| Rest of world | 42.5 | 42.5 | 42.4 |

| RA duration (years) | 9.1 ± 8.1 | 9.5 ± 8.5 | 8.6 ± 7.0 |

| Prior biologic DMARD use (%) | 20.6 | 20.5 | 19.5 |

| Seropositive for rheumatoid factor (%) | 84.4 | 87.1 | 82.6 |

| Anti-CCP antibody positive (%) | 85.4 | 90.2 | 84.9 |

| Tender joint count | 26.8 ± 13.8 | 27.2 ± 14.2 | 26.5 ± 14.5 |

| Swollen joint count | 16.7 ± 9.3 | 16.6 ± 9.0 | 16.8 ± 9.7 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 2.0 ± 2.3 | 2.4 ± 2.3 | 2.2 ± 2.4 |

| DAS28-CRP | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.9 |

| PtGA (VAS) | 63.7 ± 19.9 | 64.4 ± 20.4 | 66.3 ± 20.8 |

| Pain VAS | 63.7 ± 19.9 | 65.4 ± 21.4 | 66.7 ± 21.4 |

| HAQ-DI | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.6 |

| FACIT-F | 27.2 ± 10.4 | 26.3 ± 9.8 | 25.9 ± 10.4 |

| SF-36 PCS | 31.9 ± 6.9 | 31.5 ± 6.7 | 31.1 ± 6.8 |

| SF-36 MCS | 38.9 ± 11.4 | 39.0 ± 11.3 | 38.7 ± 12.0 |

Numbers are presented as mean ± SD unless mentioned otherwise. q2w every 2 weeks, MTX methotrexate, Anti-CCP anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, CRP C-reactive protein, DAS28-CRP 28-joint disease activity score using C-reactive protein, DMARD disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, FACIT-F functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale, HAQ-DI health assessment questionnaire disability index, SF-36 36-item Short Form Health Survey-Version 2, MCS mental component summary, PCS physical component summary, PtGA patient global assessment of disease activity, RA rheumatoid arthritis, VAS visual analog scale

Changes from baseline

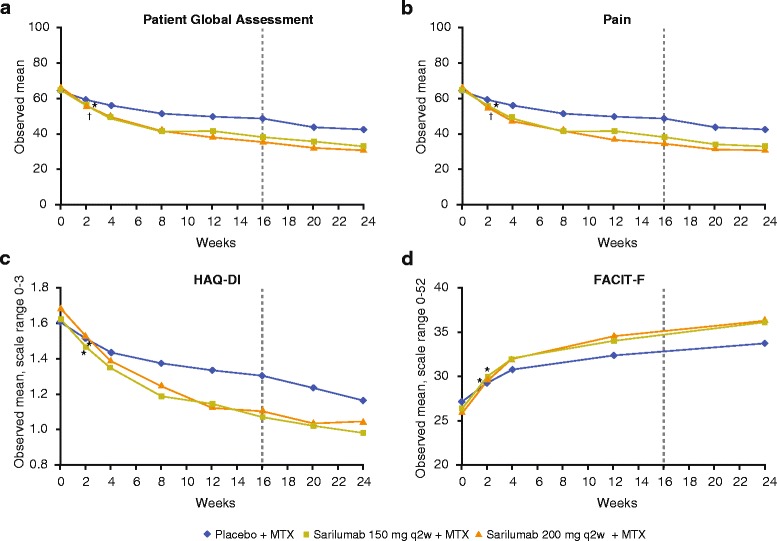

LSM improvements from baseline at week 24 in the PtGA, pain, and HAQ-DI scores were greater with sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg than placebo (p < 0.0001) and were maintained at week 52 (Table 2). The FACIT-F demonstrated improvement at week 24 with sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg that was significantly greater than placebo and was maintained through week 52 (p < 0.0001 for both doses at both time points) (Table 2). Significant improvements were reported in the SF-36 PCS and MCS scores at week 24 with sarilumab compared with placebo (p < 0.05). Greater improvements were also observed with sarilumab in all eight domains at week 24 and at week 52 (p < 0.05) with the exception of the MCS and RE scores with sarilumab 150 mg at week 52 (Table 2). Improvements in PtGA, pain, HAQ-DI, and FACIT-F scores were evident by 2 weeks after the start of treatment (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Change from baseline in patient-reported outcome scores at weeks 24 and 52

| Patient-reported outcome | (n) Least square mean ± standard error | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 24 | Week 52 | |||||

| Placebo + MTX (n = 398) | Sarilumab 150 mg q2w + MTX (n = 400) | Sarilumab 200 mg q2w + MTX (n = 399) | Placebo + MTX (n = 398) | Sarilumab 150 mg q2w + MTX (n = 400) | Sarilumab 200 mg q2w + MTX (n = 399) | |

| PtGA | (253) -15.7 ± 1.4 | (312) -28.3 ± 1.3*** | (319) -32.9 ± 1.3*** | (196) -20.3 ± 1.5 | (272) -31.7 ± 1.4*** | (272) -32.8 ± 1.4*** |

| Pain VAS | (253) -15.4 ± 1.4 | (313) -28.5 ± 1.4*** | (321) -31.8 ± 1.3*** | (196) -19.3 ± 1.6 | (273) -32.7 ± 1.4*** | (272) -33.1 ± 1.4*** |

| HAQ-DI | (253) -0.32 ± 0.03 | (313) -0.56 ± 0.03*** | (316) -0.57 ± 0.03*** | (195) -0.27 ± 0.04 | (272) -0.62 ± 0.03*** | (270) -0.63 ± 0.03*** |

| FACIT-F | (252) 5.8 ± 0.5 | (311) 8.6 ± 0.5*** | (320) 9.2 ± 0.5*** | (195) 6.1 ± 0.5 | (270) 9.1 ± 0.5*** | (271) 9.2 ± 0.5*** |

| SF-36 component scores | ||||||

| PCS | (246) 5.2 ± 0.5 | (299) 8.0 ± 0.5*** | (309) 8.4 ± 0.5*** | (187) 5.6 ± 0.6 | (257) 9.2 ± 0.5*** | (263) 9.1 ± 0.5*** |

| MCS | (246) 3.9 ± 0.6 | (299) 5.7 ± 0.6* | (309) 8.2 ± 0.6*** | (187) 5.5 ± 0.7 | (257) 7.1 ± 0.6 | (263) 8.4 ± 0.6** |

| SF-36 domain scores | ||||||

| Physical functioning | (253) 11.9 ± 1.5 | (312) 17.5 ± 1.3* | (316) 18.2 ± 1.3** | (195) 13.9 ± 1.6 | (272) 21.3 ± 1.4** | (269) 21.3 ± 1.4** |

| Role physical | (252) 12.8 ± 1.4 | (309) 18.7 ± 1.3** | (318) 20.4 ± 1.3*** | (194) 15.5 ± 1.5 | (266) 20.7 ± 1.3* | (271) 22.5 ± 1.3** |

| Body pain | (250) 15.3 ± 1.3 | (312) 25.3 ± 1.2*** | (318) 27.6 ± 1.2*** | (192) 16.7 ± 1.5 | (272) 28.1 ± 1.3*** | (269) 28.0 ± 1.3*** |

| General health | (248) 7.6 ± 1.1 | (307) 12.80 ± 1.0** | (319) 15.2 ± 1.0*** | (191) 10.5 ± 1.3 | (269) 14.5 ± 1.1* | (271) 15.9 ± 1.1** |

| Vitality | (251) 9.8 ± 1.2 | (308) 13.9 ± 1.1* | (320) 18.0 ± 1.0*** | (194) 11.4 ± 1.3 | (268) 17.5 ± 1.1** | (271) 17.7 ± 1.1** |

| Social functioning | (252) 9.8 ± 1.4 | (312) 17.3 ± 1.2*** | (320) 20.8 ± 1.2*** | (195) 11.9 ± 1.6 | (272) 20.4 ± 1.4*** | (271) 20.8 ± 1.4*** |

| Role emotional | (252) 10.3 ± 1.5 | (308) 14.6 ± 1.4* | (318) 17.9 ± 1.4*** | (193) 14.8 ± 1.6 | (264) 17.3 ± 1.4 | (269) 21.4 ± 1.4* |

| Mental health | (251) 7.4 ± 1.1 | (308) 10.4 ± 1.0* | (320) 14.0 ± 1.0*** | (194) 9.8 ± 1.2 | (268) 13.0 ± 1.1* | (271) 14.3 ± 1.1* |

q2w every 2 weeks, FACIT-F functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale, HAQ-DI health assessment questionnaire disability index, SF-36 36-item Short Form Health Survey-Version 2, MCS mental component summary, MTX methotrexate, PCS physical component summary, PtGA patient global assessment of disease activity, VAS visual analog scale. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001 versus placebo + MTX

Fig. 1.

Mean scores at each visit through week 24 for a patient’s global assessment of disease activity, b pain, c physical function, and d fatigue. Broken vertical line indicates the earliest opportunity for rescue medication; patients who did not achieve ≥20 % improvement from baseline in swollen or tender joint count on two consecutive assessments were offered rescue therapy with open-label sarilumab 200 mg every 2 weeks. HAQ-DI health assessment, FACIT-F functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue questionnaire disability index, MTX methotrexate

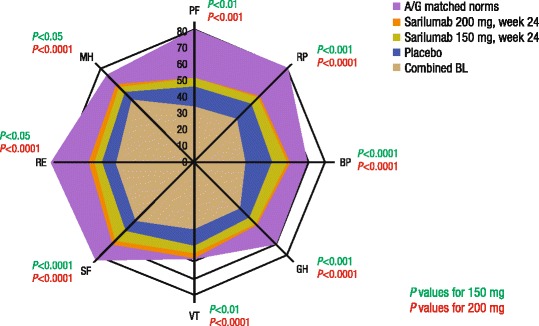

As shown in Fig. 2, the SF-36 mean baseline domain scores were approximately 20 to 50 points lower than an age-matched and gender-matched normative US population, as a benchmark comparison, indicating substantial impairment of general health status. At week 24, patients receiving both sarilumab doses reported greater improvement from baseline versus placebo across all eight domains (p < 0.05), and VT scores approached normative values.

Fig. 2.

Combined baseline (BL) and post-treatment scores at week 24 across all Short Form 36 (SF-36) domains relative to age-adjusted and gender-adjusted norms (A/G matched norms) for the US general population. All scores on a 0–100 scale (0 = worst, 100 = best). PF physical functioning, RP role physical, BP body pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, MH mental health. Note, as combined baseline scores are presented, change from baseline for each cohort cannot be inferred from Fig. 2 alone

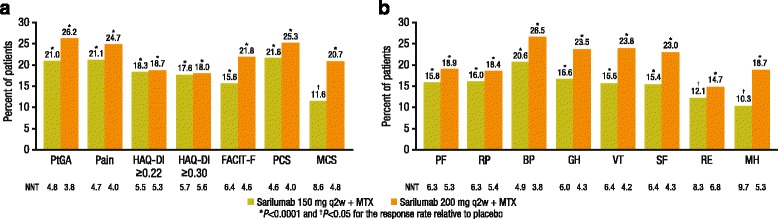

Responder analyses

In post hoc analyses, the percentages of patients reporting improvement equal to or greater than the MCID were higher with both doses of sarilumab than placebo across all PROs (p < 0.05), resulting in a NNT ranging from 4.0 (PCS for sarilumab 200 mg) to 8.6 (MCS for sarilumab 150 mg) (Fig. 3a). The percentage of patients who reported improvement equal to or greater than the MCID in individual SF-36 domains was consistently higher with both doses of sarilumab versus placebo for all domains (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b); the NNT ranged from 3.8 (BP with the sarilumab 200 mg dose) to 9.7 (MH with the sarilumab 150 mg dose). The majority (59.4–89.8 %) of ACR20 responders reported clinically meaningful improvement across PROs.

Fig. 3.

Responder analyses for patients with improvement equal to or greater than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). a Differences from placebo in the percentage of patients reporting improvement equal to or greater than the MCID after 24 weeks of treatment according to patient global assessment (PtGA), pain, functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F), health assessment questionnaire-disability index (HAQ-DI), and the Short Form 36 (SF-36) physical and mental component scores. b Differences from placebo in the percentage of patients reporting improvements equal to or greater than the MCID after 24 weeks of treatment in SF-36 domain scores. PF physical functioning, RP role physical, BP body pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, MH mental health, NNT number needed to treat for sarilumab + methotrexate (MTX) versus placebo + MTX

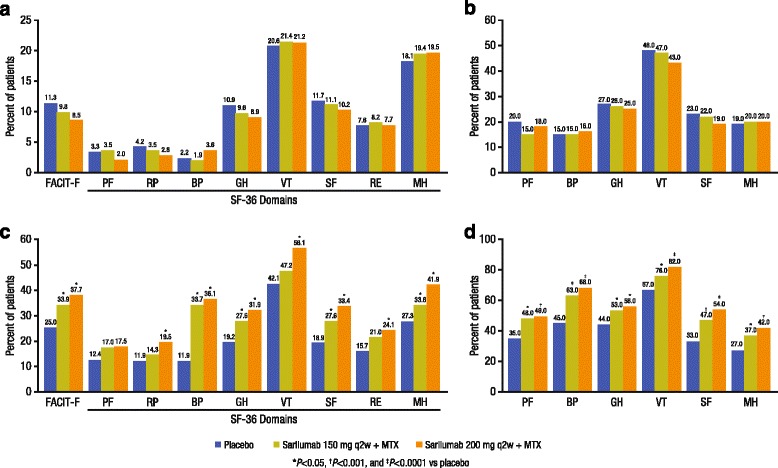

The percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than normative values in the FACIT-F and SF-36 domains was low across treatment groups at baseline, ranging from 1.9 % for BP to 21.4 % for VT (Fig. 4a), although higher proportions reported values exceeding PASS thresholds (from 15 % for BP to 48 % for VT) (Fig. 4b). At week 24, the percentage of patients who reported scores equal to or greater than normative values across the FACIT-F and SF-36 domains was greater with sarilumab treatment in the individual domains of BP, GH, SF, and MH domains with 150 mg, and across all domains with 200 mg except PF (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4c). The percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than PASS was also higher with both doses of sarilumab relative to placebo (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4d), and the percentage was higher than those who reported scores equal to or greater than normative values in each of these domains.

Fig. 4.

Responder analyses for normative scores and patient acceptable symptom state (PASS). a Percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than normative values on the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) and Short Form 36 (SF-36) at baseline. b Percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than PASS thresholds at baseline. c Percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than normative values on the FACIT-F and SF-36 at week 24. d Percentage of patients reporting scores equal to or greater than PASS thresholds at week 24. PF physical functioning, RP role physical, BP body pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, MH mental health

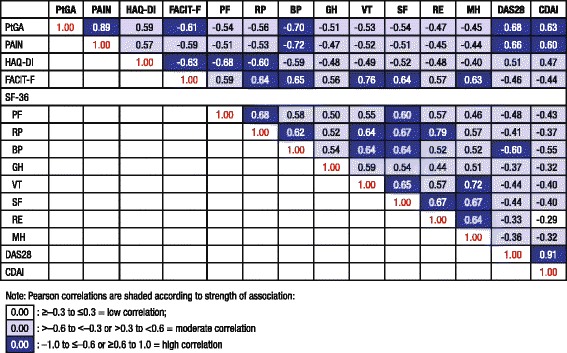

Correlation analysis

At week 24, reported PRO scores demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with clinical measures of disease activity (DAS28 and CDAI) except for RE with the CDAI (Fig. 5). There was also moderate to strong correlation between PROs and individual SF-36 domains, with the strongest correlation between domains that measure similar constructs: the FACIT-F with VT (r = 0.76), HAQ-DI with PF (r = -0.63) and VAS pain with BP (r = -0.72).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between observed patient-reported outcomes and disease activity scores at Week 24

Discussion

In this phase III RCT, patients with moderate to severely active RA, who were MTX-IR reported that treatment with sarilumab + MTX resulted in improvements in pain, physical function, fatigue, and general health status that were clinically meaningful and greater than with placebo + MTX. These results complement the clinical efficacy previously reported [4].

There was concordance across PROs, with durable responses that appeared as early as 2 weeks in PtGA, pain, physical function, and fatigue scores, which were sustained through week 52. Improvements with 200 mg were generally greater than with the 150 mg dose. The FACIT-F scores showed significant and clinically meaningful improvement with sarilumab treatment; fatigue has a substantial impact in RA [19] and may be of greater patient concern than other signs and symptoms such as tender and swollen joints [20].

Responder analyses demonstrated benefit using a variety of approaches. In addition to reporting improvements equal to or greater than the MCID in PtGA, pain, HAQ-DI and FACIT-F scores that exceeded placebo, the proportions of responders at 24 weeks were greater across all PROs with both sarilumab doses than placebo. These responses resulted in a NNT ranging from 3.8 to 5.4 with sarilumab 200 mg, indicating that few patients would need to be treated to achieve clinically meaningful improvement. It is worth noting that the responder analysis conducted in this study was based on a conservative approach; patients who discontinued or received rescue medication were considered non-responders rather than as missing data.

As in other RCTs of biologic DMARDs [21–24], low baseline SF-36 scores indicated substantial impairment of general health status when compared with an age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US normative population, with significant improvements after treatment. Furthermore, using a higher level of response, i.e., improvement equal to or greater than the normative values for SF-36 PCS and MCS (≥50) and SF-36 domains based on this specific protocol population, were significant with sarilumab versus placebo. The achievement of normative values is also a more meaningful response than PASS, which represents a threshold of acceptability rather than demonstrating parity with an age-matched and gender-matched population, without arthritis or comorbidities. Together, these data indicate that active treatment with both doses of sarilumab improved health status and fatigue to levels commensurate with a patient population without arthritis or co-morbidities typical in RA.

Indeed, while correlation between symptoms/disease activity and functional outcomes suggested that clinical effects translate into patient-reported improvement in PtGA, pain, physical function and general health status, many of the correlations between the observed scores between PROs at week 24 were only moderate, indicating that these measures assess different domains of response and reflect relief from the broad burden of disease on patients’ lives.

A limitation of this study is that other than PtGA and HAQ-DI, all PROs were generic and do not specifically query about RA. However, all PROs utilized do assess concepts relevant to patients with RA and have been well-validated for use in RA. Additionally, the use of hierarchical testing procedures limited the ability to interpret some PRO data with regard to claims of statistical significance. Generalizability of the NNT estimates may also be limited because the comparator group, placebo + MTX, may not necessarily reflect clinical practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, reductions in disease activity with sarilumab treatment are associated with patient-reported benefits in global disease activity, pain, physical function, fatigue, and general health status. These effects, reported as early as week 2 and maintained over the 52-week trial duration, provide evidence of long-term benefits.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Clare Proudfoot, PhD, and Matthew Reaney, MSc, of Sanofi for their contribution to the analyses and revisions of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Funding for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript was also provided by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

VS, MK, CC, GJ, and RR-B were involved in development of the statistical analysis plan, and contributed to interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. CF provided input on the statistical analysis plan, was involved in the statistical analysis, and contributed to drafting of the manuscript. NMHG, HvH, and MB provided critical input on study design, and contributed to interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. TH and MCG were involved in the acquisition and interpretation of the data, and contributed to drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

VS has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Afferent, Amgen, Biogen, Bioventus, BMS, Carbylan, Celgene, Celltrion, Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA), Crescendo Bioscience, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, GSK, Hospira, Iroko, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Sanofi Genzyme, SKK, Takeda, UCB, and Vertex. MK has received consulting fees from Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. CC and NMHG are employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. GJ was an employee of Sanofi Genzyme when the study was conducted and may hold stock in Amgen and Pfizer. RR-B has received consulting fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. HvH and CF are employees of Sanofi Genzyme and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. MB is an employee of Optum, which provides services to Sanofi Genzyme. TWJH has received lecture or consulting fees from Merck, UCB, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biotest AG, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Abbott, Crescendo Bioscience, Nycomed, Boehringer, Takeda, Zydus, and Eli Lilly. MCG has received research grants and/or consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, R-Pharma, Roche, RuiYi, and Sanofi Genzyme. No author has a nonfinancial competing interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board and Independent Ethics Committee of the investigational centers and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The specific ethical bodies that approved study EFC11072-Part B are as follows: CIE Para Ensayos en Farmacologia Clin Prof Dr Luis M. Zieher Jose E. Uriburu, Buenos Aires; CIEIS - Italiano De Cordoba Roma, Córdoba; Comité de Etica Instituto Strusberg, Córdoba; CIEM-NOA Las Piedras, Tucumán; CIEFA Uruguay, Buenos Aires; Instituto De Investigaciones Clínicas Zarate F. Andrade, Buenos Aires Province; Dim Clínica Privada Belgrano, Buenos Aires Province; CECIC - Comité de Ética de CER Investigaciones Clínicas Vicente Lopez, Buenos Aires Province; Instituto De Investigaciones Clínicas Avda, Buenos Aires Province; Redcliffe-Caboolture Health Service District Ethics Committee, Queensland; Sydney Local Health Network (SLHN) Ethics Review Committee, New South Wales; Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee Austin Hospital, Victoria; Human Research Ethics Committee (TQEH/LMH/MH) The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, South Australia; Royal Brisbane Hospital EC Royal Brisbane Hospital & Women’s Hospital Health, Queensland; ACT Health Human Research Ethics Committee Canberra Hospital, Australian Capital Territory; Bellberry Human Research Ethics Committees, South Australia; Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Universität Graz, Graz; EK der Stadt Wien gemäß KAG, AMG und MPG Town, Wien; CHU de Liège Domaine Universitaire du Sart-Tilman, Liège; EC of Hospital das Clínicas da Univ. Federal do Parana Rua General Carneiro, Parana; Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa - CONEP Edifício Ex-INAN - Unidade II, Brasilia; EC of Instituto de Assistancia Medica Servidor Publico Estadual, Sao Paulo; Ethics Committee of Hospital Heliopolis Rua Conego Xavier, Sao Paulo; EC of Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul; EC of Hospital Universitario Pedro Ernesto, Rio de Janeiro; Ethics Committee of Hospital Geral de Goiania, Goias; EC of Pontifícia Univ. Católica de Campinas, Sao Paulo; EC of Hospital Universitario da Univ Federal de Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais; Ethics Committee Prof. Dr. Celso Figueiroa SCMBA Praca Conselheiro Almeida Couto, Bahia; EC of Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas UNICAMP, Sao Paulo; EC of Centro Integrado de Atencao a Saude - UNIMED Vitoria, Espirito Santo; Local Ethics Committee of the City Clinical Hospital Number 9, Minsk; LEC of the Clinical Hospital 6, Minsk; Institutional Review Board Services, Aurora; University Health Network Research Ethics Board, Toronto; Comité de Ética de la Investigacion S.S.M Centra, Santiago; Comité de Ética Científico S.S. M Oriente, Santiago; Comité Etico de Investigacion Servicio de Salud Valdivia, Valdivia; Comité de Ética de la Investigacion S.S. Viña Quillota, Vina Del Mar; Comité de Ética de la Investigacion S.S.M Sur Oriente, Santiago; Comité de Ética de la Investigacion S.S.M. Sur; Santiago; Comité de Ética Cientifica del Servicio de Salud del Maule, Talca; National Taiwan University Hospital 7, Taipei; Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Institutional Review Board) Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Number 5, Taoyuan; CIE en Investigacion del H. Militar Central, Bogotá; Comité de Investigaciones y Etica en Investigaciones, Medellin; Comité de Etica en Investigacion de la Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla; Comité de Ética de la Investigacion Riesgo de Fractura, Bogotá; Comité de Ética en Investigaciones del Oriente, Bucaramanga; Fundacion Instituto de Reumatologia Fernando Chalem, Bogotá; Comité de Etica en Investigacion de Servimed EU, Bucaramanga; Tallinn Medical Research Ethics Committee, Tallinn; HUS Medisiininen Eettinen Toimikunta Biomedicum Helsinki 2 C, Helsinki; Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Medizinischen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Münster; Fachbereichs Medizin der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main; Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Fakultät Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen; Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg, Hamburg; Ärztekammer Niedersachsen Ethikkommission zur Beurteilung Medizinischer Forschung am Menschen, Hannover; Ethik-Kommission des Landes Berlin Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales Berlin, Berlin; Ethik-Kommission I der Medizinischen Fakultät Heidelberg, Heidelberg; Ethik-Kommission des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Dessau-Rosslau; National Ethics Committee 284, Messoghion, Athens; Medical Research Council, Ethics Committee for Clin. Pharm., Budapest; Center for Rheumatic Diseases (CRD) Ethics Committee CRD, 11, Hermes Elegance, Pune; Medanta Independent Ethics Committee Medanta - The Medicity, Gurgoan; CMMH National Ethics Committee National Ethics Committee, Chennai; IEC of Sri Deepti Rheumatology Center Sri Deepti Rheumatology Center, Hyderabad; Institution Ethics Committee #149, Bangalore; Penta Med Ethics Committee Medipoint Hospitals PVT LTD, Pune; KIMS Institutional Ethics Committee, Secunderabad; Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow; Gachon University Gil Hospital IRB, Incheon; CMC Central IRB, Seoul; Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul; Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook Nat’l Univ. Hospital, Daegu; IRB of Eulji University Hospital, Daejeon; Pusan National University Hospital, Busan; Institutional Review Board of National University Hospital, Seoul; Ajou University Hospital, Gyeonggi-do; Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital, Incheon; Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju; Institution Review Board of Chonbuk National University Hosp, Jeollabuk-do; The Hospital for Rheumatic Disease Hanyang University, Seoul; Institutional Review Board of Hallym Sacred Heart Hospital, Gyeonggi-do; Medical Research & Ethics Committee C/o Institute for Health Management, Kuala Lumpur; Comité Bioetico para la Investigacion Clínica S.C., México, D.F.; CEI Centro de Estudios de Investigación Básica y Clínica SC, Jalisco; CEI Centro de Especialidades Médicas del Sureste, S.A.de C.V., Yucatan; Comité de Ética Faculdad de Medicina de la UANL y HU, Nuevo Leon; Comité de Ética de la F. de Med. de la UAEM Paseo Tollocan S/N Col., Estado de México; Comision de Investigacion Etica y Bioseguridad Cen. Esp. en Diab., Ob. y Prev. de Enf. Cardiovasc., SC, México, D.F.; CEI Unidad de Atención Médica e Invest. en Salud (UNAMIS), Yucatan; Multi-region Ethics Committee NZ Multi-region EC, Wellington; Regional Komité for Medisinsk og Helsefaglig Forskningsetikk, Oslo; Institutional Review Board-University of Sto. Tomas Hospital University of Sto. Tomas Hospital, Manila; UP PGH-RIDO Philippine General Hospital, Manila; Cebu Doctors University Institutional Ethics Review Committee, Cebu; Komisja Bioetyczna przy Kujawsko-Pomorskiej Okr. Izbie Lekar, Kujawsko-pomorskie; CEIC - Comissão de Ética para a Investigação Clínica, Lisboa; National Ethics Committee for Clinical Trial of the Medicine, Bucharest; LEC of the Scientific Research Institute of Rheumatology, Moscow; National Ethics Committee of the Russian Federation, Moscow; Russian State Medical University, Moscow; LEC of Aviation Clinical Hospital #7, Moscow; LEC of the Kemerovo State Medical Academy, Kemerovo; LEC of the Hospital #25, Saint-Petersburg; LEC of t Dzhanelidze Research Institute, Saint-Petersburg; LEC of Immunology Research Institute, Novosibirsk; LEC of Samara Region Hospital named after M.I. Kalinin, Samara; LEC of the Saratov State Medical University, Saratov; LEC of the Central Clinical Hospital with Outpatient Department, Moscow; LEC of Republican Clinical Hospital named by G.G. Kuvatov, Ufa; LEC of the City Clinical Hospital #26, Saint-Petersburg; Ryazan Regional Clinical Cardiological Dispensary, Ryazan; LEC of the Kemerovo Regional Clinical Hospital, Kemerovo; LEC of ‘Applied Medicine,’ Moscow; Wits Human Research EC, Gauteng; Pharma Ethics (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria; University of Kwazulu-Natal, Biomedical Research Ethics Committee, Durban; The Research Ethics Committee, University of Pretoria Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria Gauteng; CEIC Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; The Ethical Clearance Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok; The Ethical Committee on Research Involving Human Subject Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok; LEC of Central City Clinical Hospital #1, Donetsk; LEC of Railway Clinical Hospital, Dnipropetrovsk; LEC of “M.D. Strazhesko Institute of Cardiology of AMS of Ukraine,” Kyiv; LEC of City Clinical Hospital #4, Lviv; LEC of “University Clinic,” Simferopol; LEC of Oleksandrivska Clinical Hospital, Kyiv; LEC of Municipal Institution “Zaporizhzhya Regional Clinical Hospital,” Zaporizhzhya; LEC of Kharkov Regional Clinical Hospital, Khark; Compass IRB, Mesa, AZ; Emory University IRB, Atlanta, GA; Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board, Cincinnati, OH; IRB - University of Florida Health Center Institutional Review Board, Gainesville, FL; New York University School of Medicine IRB, New York, NY; Ethics Committee of Centro de Ciencias da Saude UFPE, Pernambuco; Ethik-Kommission der Landesärztekammer in Hessen, Frankfurt; Ethics Committee for Research on Human Subject Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai; Ethics Committee on Clinical Trials Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, Delhi; Institutional Ethics Committee CSSMU Office of the Research Cell of C.S.M. Medical University, Lucknow; Ethics Committee of Care Institute of Medical Sciences CIMS Hospitals, Ahmedabad; Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu-si; Ministry of Health Ethics Committee, Ankara; Research Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine Cairo University, Cairo; WIRB, Olympia, WA; University of California, San Diego IRB, La Jolla, CA; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center IRB, Dallas, TX. All patients provided written, informed consent prior to study participation.

Abbreviations

- ACPA

anti-citrullinated protein antibody

- ACR

American college of rheumatology

- ACR20

American college of rheumatology 20 % improvement response

- BP

body pain

- CDAI

clinical disease activity index

- DAS28-CRP

28-joint disease activity score using C-reactive protein

- DMARD

disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

- FACIT-F

functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue

- GH

general health

- HAQ-DI

health assessment questionnaire disability index

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LSM

least squares mean

- MCID

minimal clinically important difference

- MCS

mental component summary

- MH

mental health

- MMRM

mixed model for repeated measures

- MTX

methotrexate

- MTX-IR

methotrexate inadequate response

- NNT

number needed to treat

- PASS

patient acceptable symptom state

- PCS

physical component summary

- PF

physical function

- PRO

patient-reported outcome

- PtGA

patient global assessment of disease activity

- q2w

every 2 weeks

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RCT

randomized, controlled trial

- RE

role emotional

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- RP

role physical

- SD

standard deviation

- SF

social functioning

- SF-36

36-item Short Form Health Survey

- VAS

visual analog scale

- VT

vitality

Contributor Information

Vibeke Strand, Phone: 650-529-0150, Email: vstrand@stanford.edu, Email: vibekestrand@me.com.

Mark Kosinski, Email: mkosinski@qualitymetric.com.

Chieh-I Chen, Email: chieh-i.chen@regeneron.com.

George Joseph, Email: george.j.joseph@gmail.com.

Regina Rendas-Baum, Email: rrbaum@qualitymetric.com.

Neil M. H. Graham, Email: neil.graham@regeneron.com

Hubert van Hoogstraten, Email: Hubert.vanHoogstraten@sanofi.com.

Martha Bayliss, Email: mbayliss@qualitymetric.com.

Chunpeng Fan, Email: Chunpeng.Fan@sanofi.com.

Tom Huizinga, Email: t.w.j.huizinga@lumc.nl.

Mark C. Genovese, Email: genovese@stanford.edu

References

- 1.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T, Hughes RA, Carr M, Hehir M, et al. Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis–progress at OMERACT 7. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(11):2250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirwan JR, Tugwell PS. Overview of the patient perspective at OMERACT 10–conceptualizing methods for developing patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1699–701. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Kivitz AJ, Rell-Bakalarska M, Martincova R, Fiore S, et al. Sarilumab plus methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1424–37. doi: 10.1002/art.39093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaible HG. Nociceptive neurons detect cytokines in arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(5):470. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohleder N, Aringer M, Boentert M. Role of interleukin-6 in stress, sleep, and fatigue. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1261:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):261–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, Chartash E, Sengupta N, Grober J. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(5):811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker D, Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-36v2™ Health Survey. 2. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(3):557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, Kirwan JR, Kvien TK, Tugwell PS, et al. It’s good to feel better but it’s better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1720–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strand V, Smolen JS, van Vollenhoven RF, Mease P, Burmester GR, Hiepe F, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate provides broad relief from the burden of rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of patient-reported outcomes from the RAPID 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):996–1002. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.143586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubeck DP. Patient-reported outcomes and their role in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(Suppl 2):27–38. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osiri M, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wells GA, Robinson V, Tugwell P. Number needed to treat (NNT): implication in rheumatology clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(4):316–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiberg T, Kvien TK, Mowinckel P, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, Hagen KB. Identification of disease activity and health status cut-off points for the symptom state acceptable to patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(7):967–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.077503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rendas-Baum R, Bayliss M, Kosinski M, Raju A, Zwillich SH, Wallenstein GV, et al. Measuring the effect of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials from the patient’s perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(7):1391–403. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.896328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, Kirwan J, Richards P, Carr A, et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: how important are they? Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(3):131–42. doi: 10.1002/msc.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mease P, Strand V, Shalamberidze L, Dimic A, Raskina T, Xu LA, et al. A phase II, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study of BMS945429 (ALD518) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1183–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strand V, Mease P, Burmester GR, Nikai E, Coteur G, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Rapid and sustained improvements in health-related quality of life, fatigue, and other patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate over 1 year: results from the RAPID 1 randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):R170. doi: 10.1186/ar2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strand V, Kremer J, Wallenstein G, Kanik KS, Connell C, Gruben D, et al. Effects of tofacitinib monotherapy on patient-reported outcomes in a randomized phase 3 study of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to DMARDs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:307. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0825-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strand V, Kosinski M, Gnanasakthy A, Mallya U, Mpofu S. Secukinumab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with incremental benefit in the clinical outcomes and HRQoL improvements that exceed minimally important thresholds. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]