Abstract

The symptoms of Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) include blistering of skin on superficial layers due to the exfoliative toxins released from Staphylococcus aureus. After the acute exfoliation of skin surface, erythematous cellulitis occurs. The SSSS may be confined to few blisters localized to the infection site and spread to severe exfoliation affecting complete body. The specific antibodies to exotoxins and increased clearence of exotoxins decrease the frequency of SSSS in adults. Immediate medication with parenteral anti-staphylococcal antibiotics is mandatory. Mostly, SSSS are resistant to penicillin. Penicillinase resistant synthetic penicillins such as Nafcillin or Oxacillin are prescribed as emergency treatment medicine. If Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected), antibiotics with MRSA coverage (e.g., Vancomycin or Linezolid) are indicated. Clindamycin is considered as drug of choice to stop the production of exotoxin from bacteria ribosome. The use of Ringer solution to to balance the fluid loss, followed by maintainence therapy with an objective to maintain the fluid loss from exfoliation of skin, application of Cotrimoxazole on topical surface are greatlly considered to treat the SSSS. The drugs that reduce renal function are avoided. Through this article, an attempt has been made to focus the source, etiology, mechanism, outbreaks, mechanism, clinical manisfestation, treatment and other detail of SSSS.

Keywords: Outbreaks, Pathophysiology, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is counted as one of the major skin infections. In this infection, skin surface of large parts of body gets peeled off and looks like burned skin by hot liquid [1]. SSSS is also called as Ritter von Ritterschein disease, Ritter disease, Lyell disease and staphylococcal necrolysis of epidermis. The disease generally occurs in new borns, having remarkable blistering on superficial surface of skin caused by the exfoliative toxins released from Staphylococcus aureus [2, 3].

The symptoms of this disease include skin surface exfoliation followed by acute erythematous cellulitis [4]. Intensity of SSSS varies from a few watery blisters on some part of skin to a severe exfoliation affecting the entire body surface. These red blisters on skin surface looks like scaled or burned therefore, this infection has been termed as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome [5]. Toxin producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus produce two exotoxins naming epidermolytic toxins A and B. These toxins form the basis of SSSS infection [6, 7]. Desmosomes (an integral part of skin) acts to adher the adjacent skin cell. The toxins from Staphylococcus aureus bind to molecule (Desmoglein 1) within the desmosome and get broken up in a manner so that skin cells loose adherence [8].

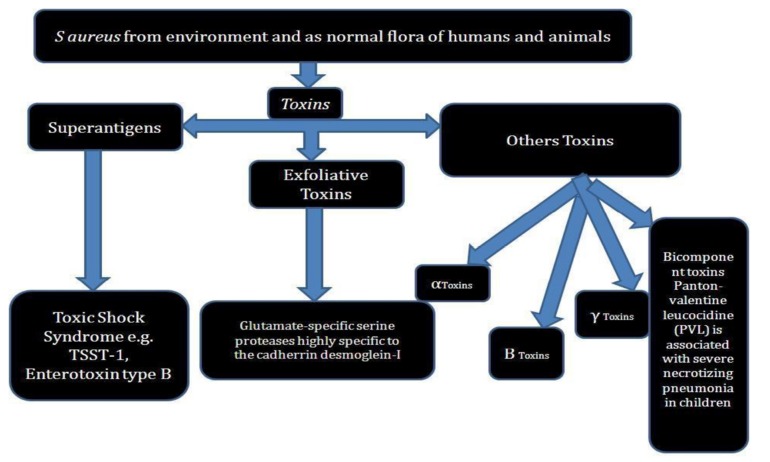

S. aureus and Toxins

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram (+) coccal bacterium and its occurrence is found near nose and nearby skin surface. The cases of pathogenecity of S. aureus is not observed everytime but even in some cases causes skin infections such as blisters, lung infections and food poisioning etc. Few strains of this pathogenic bacterium often cause infections by releasing the toxins and with some surface proteins, which upon binding causes inactivation of antibodies. MRSA infection is caused by species of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics being used to cure many ordinary infections. Strains of S. aureus secrete several exotoxins of three types [8, 9].

Superantigens

Superantigen induces syndrome disease like condition commonly known as toxic shock syndrome (TSS). TSS comprises of type B enterotoxin TSST-1 which causes TSS disease associated with tampon use. The symptom includes pyrexia, rashes on erythematous surface, hypotension like condition, multiple organ working failure, shock and desquamation of skin from epidermis etc. Absence of antibody against TSST-1 leads to pathogenesis of TSS [10]. S. aureus gastroenteritis is being caused by an enterotoxin produced from some strains of S. aureus. The bacteria induced gastroenteritis is self-limiting and identified by vomiting and diarrhea, with recovery time of 8 to 24 h. Other symptoms of this gasteroenteritis include presence of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and severe pain in lower abdomen [11, 12].

Exfoliative toxin (EF)

This kind of toxin is mostly observed in the case of infants and young children having Staphylococcal infection. The nurseries associated with hospitals may also posses EF. The released exfoliative toxins and their protease activity cause peeling off effect on skin surface [13].

Other toxins

Some other Staphylococcal toxins acting upon cell surface are alpha (α) toxins, beta (ß) toxin, delta (δ) toxin, and Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). PVL toxin is related with intense necrotizing pneumonia specially in children [14, 15]. Recent study has revealed that PVL encoding conducted on bacteriophage occurring in community associated MRSA strains has opened new opportunity of further research.

Carriers of S. aureus

The carriage from nose contains strains of S. aureus in 35% of the population but this percentage may vary depending upon age and race. The patients of contact dermatitis, psoriasis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and atopic dermatitis are pronounced carrier of S. aureus. The outbreak of SSSS may be correlated with such carriers [16]. The occurrence of bacteria in neonates is very common especially on the skin, eyes, wound surface and umbilical stumps. The nursing homes and hospitals are counted as common sources of S. aureus, because of insufficient infection control practices, e.g. regular hand wash and cleaning stethoscopes between each patient. Newborns are at high risk of SSSS as bacteria are colonized within 6-days of birth. A study revealed that around 80% cases of SSSS occur in neonates, which are discharged from hospitals, especially in areas where the antiseptic umbilical cord care is discouraged. So far as the outbreak of SSSS is concerned, more bacterial colonization in neonates occurs from nursery attendants rather than mothers [17-19].

RISK ASSOCIATED WITH SSSS

Neonates and children of age group less than 5 years are generally at high risk of SSSS. In order to combat against SSSS, in childhood, body acquires lifelong immunity in form of antibodies against exotoxins of staphylococcal strain, which reduces the chance of SSSS in older children and adults [20]. Reduced immunity against bacterial exotoxins and imperfect renal clearance enhance the chance of SSSS in the neonates. The reason behind the fact includes that exotoxins are cleared through kidneys. It indicates that irrespective of age and sex, immunocompromised individuals and patients of renal failure are at risk of SSSS [21].

SPREADING OF SSSS

Infection arising from staphylococcal bacteria produces two types of toxins which include epidermolytic toxins A and B. An asymptomatic adult carrier of S. aureus transfers the bacterial strain into the neonates. Recent study has reported that about 15-40% of humans carry the S. aureus in their skin without any sign and symptom of infection [22, 23].

In neonates, the immune and renal systems are underdeveloped therefore; chance of occurrence of SSSS is more in neonates. Very rarely, SSSS infection occurs in adults, but the chances in immunocompromised and renal failure patients’ cannot be ignored, as well as the patients taking the immune suppressant drugs or undergoing chemotherapy.

The staphylococcus bacteria are transferred from person to person by sharing towels or by droplets of coughing. Apart from this, persons who carry the bacteria but have no sign and symptom of infection can also transmit bacteria. Source of S. aureus is body organs including throat, ears and eyes [24, 25].

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SSSS

In general, starting symptom of SSSS includes fever and redness on entire surface the skin. Within 24-48 h, blisters with fluid accumulation are formed on the entire body. The blisters are ruptured and the resulting area appears as a burn. Large area of skin surface is peeled off or fall away showing the symptoms of exfoliation or desquamation.

In the SSSS, skin peeled off with gentle touch and leaves wet red areas appearing as burned skin (Nikolsky's sign) [26, 27].

Symptoms on Skin

In the area of groin, armpits, nose and ears, fluid accumulated blisters looking like tissue paper . The skin rashes spread rapidly into other legs and trunk. Diaper area of newborns is a very common place of skin rashes associated with SSSS. After 24 h of infection, the skin surface is peeled off in small sheets, leaving moist and reddish area on topical surface. Other symptoms of SSSS include intense pain around the infection site, weakness, fatigue and dehydration [28].

IDENTIFICATION OF SSSS

The appearance of skin itself clearly shows symptoms of SSSS. The oozed liquid or pus wrapped in cotton swab is used to identify the presence of the staphylococcal bacteria. Blood test is conducted in some cases to confirm the infection. Small skin piece is generally sent for microscopic examination [28].

In order to diagnose, the healthcare provider asks about the child’s symptoms and medical history. The tests of skin biopsy and culture examination may also be performed to confirm the diasease condition.

Biopsy of Skin sample

Small skin sample is observed under the microscope.

Culture test

Culture test is performed to check the presence of specific bacteria. For culture, sample of blood, urine, nose, throat and skin are used. For neonates, culture of the umbilicus is done to diagnose SSSS [28, 29].

The main diagnostic features of SSSS are burn like epidermal exfoliation and damage of soft mucosa including oral mucosa and even in some cases vaginal mucosa. Few drugs have potential to cause toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Irrespective of drug induced tissue necrolysis, in SSSS, there is necrolysis in all epidermal layers and prominent infiltration to the mucous membranes.

In the United Kingdom (UK), diagnosis of SSSS depends on clinical grounds, supported by the presence of S. aureus in nasal, conjunctival, pharyngeal, umbilical etc. but reliability of these parameters is still questionable [30]. In UK, the isolates are sent to the Public Health Laboratory (PHL), London, where the S. aureus would be phage typed. The presence of S. aureus in phage group II will strongly support the diagnosis of SSSS, even though other phage types show an identical clinical features [31]. For more confirmation, the PHL use immunological Ouchterlony method for toxins, which fails in sensitivity and specificity [32].

Serological gel immunoprecipitation, radioimmunological assays (RIA), enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), gene sequence detection by DNA hybridization and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are recently developed detection system for exfoliative toxins of SSSS [33]. False positive results might be observed in serological evaluation because of protein A (a 42 kDa protein produced by over 90% of S. aureus), as it binds with constant (Fc) domain of immunoglobulins (IGs). The major drawback of these diagnostic techniques is that these are mean for laboratory-based research rather than clinical applications and the techniques are too costly and time consuming for routine analysis [34].

DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF SSSS IN DIAGNOSIS

Since past years, SSSS and TEN were assumed as same due to similarity in clinical characteristics. However, the pattern of skin peeling differs and TEN occurs due to drug reaction. However, using the skin biopsy can clearly differentiate between the two [35].

The exotoxin produces toxic shock syndrome and fever, which is called as Staphylococcal scarlet fever. This fever affects mainly children and the simple erythematous rash, without blisters or Nikolsky's sign, which is observed on days 5-10 followed by desquamation.

-

Pemphigus (group of autoimmune disorders having blistering of the skin and/or mucosal surfaces) differs from SSSS [36]. The word Pemphigus was used to include most bullous eruptions but better diagnostic tests intended for reclassification of bullous diseases. The bullae are superficial and confined to the epidermal layer. This is different to bullous pemphigoid in which bullae are on subepidermal surface. The major subclasses of the disorder are mentioned below with clinical characteristic and immunological attributes [37]:

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV): It is the very common and accounts for 70% of pemphigus cases.

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF): The main charactestic feature of PF is the presence of skin lesions but this is directly related with antibodies to desmoglein 1 (DSG1).

Others: This class includes Pemphigus herpetiformis, IgA pemphigus, paraneoplastic pemphigus and IgG/IgA pemphigus and these forms are observed very rarely.

INVESTIGATION

The collected skin swabs are subjected to bacteriological confirmation and antibiotic sensitivities to identify the SSSS. The frozen skin biopsies of the lesions may be used to confirm the SSSS. In general, skin blisters give negative result in culture test, but S. aureus develops from some prominent site of infection as umbilicus, conjunctiva, breast, surgical wound, nasopharynx, blood. The patient and immediate relatives should be screened for asymptomatic nasal carriers of S. aureus [28].

The diagnosis of SSSS may be confirmed by the biopsy (taking a tissue sample of the infected area and microscopic examination of bacterial culture (by colonizing the collected sample to identify the causative organism).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

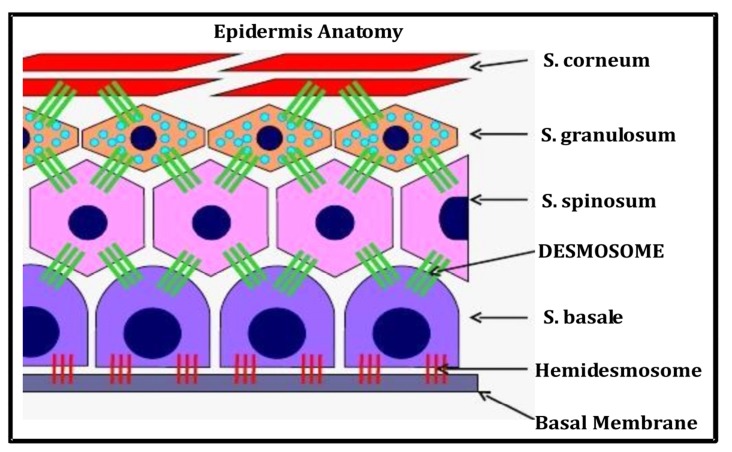

The skin is the largest organ in the human body containing five sublayers viz. Stratum corneum, Stratum lucidum, Stratum granulosum, Stratum spinosum, Stratum germinativum (Fig. 1). Below to the epidermis, a layer of dermis exists which is comprised of some tissues and acts to cushion the dermis from stress. Desmosome is a cell organelle responsible for adhesion among cells. Desmosomes are localized and spot-like structure but systemically arranged on the lateral end of cell membranes. The main action of desmosomes is to resist shearing forces and is found in simple and stratified squamous epithelium. In relation with SSSS, desmosomes are directly concerned [38, 39]. The desmosomes found in muscle tissue act to bind muscle cells to one another.

Fig. (1).

Anatomy of skin epidermis.

Exfoliative toxin A released from Staphylococcus aureus, causes blisters in skin surface and is known as staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. The toxin causes loss of cell adhesion in the epidermis. The skin damage is caused by release of epidermolytic toxins [40]. The released toxins are biochemically serine proteases and are circulated from a localized source, leaving epidermal erosion at distant sites (Fig. 2). It results into breakage of the desmoglobin 1, which acts as adhesion molecule, breaking up the skin by inhibiting the adhesion of skin cells. The detachment of superficial skin surface is the main symptom of SSSS. The exfoliative toxin attacks on Desmoglobin, which is responsible for cell-cell sticking leading to superficial lesion [41, 42].

Fig. (2).

Pathophysiology of SSSS.

TREATMENT OF SSSS

Supportive nursing care and focus to provide the fluid and electrolyte results in quick recovery from SSSS. Hospitalization is required to treat SSSS because antibiotics through intravenous route (i.v.) are necessary for absolute recovery from SSSS. Flucloxacillin (a penicillinase resistant, anti-staphylococcal antibiotic) is used sometimes. Oral antibiotics are also used after few days of treatment to replace antibiotics of i.v. route. In general, the patient of SSSS gets discharged from hospital with 6-7 days but advised to continue treatment afterwards, may be upto 15 days. Moist and ruptured skin surface require a layer of bland emollient to reduce tenderness. Paracetamol is usually first line drug to treat fever and pain associated with SSSS. It is given when necessary. Skin surface requires intense care as the skin is very fragile in SSSS patient. Topically, the therapy including either Fusidic acid or Mupirocin is applied as these drugs have proven cases of bacterial resistance [43, 44]. Intravenous immunoglobulin had also been recommended to combat Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, but a recent study associates its use with prolonged hospitalization [45]. In a case reported in 2015, they used a double antibiotic therapy combining ceftriaxone and aminoside and also added important rehydration, antipain, and skin care with eosin liquid of 1% [46].

After start of blistering on skin surface in SSSS, initial 48 h are treated as critical but afterwards the disease is not considered as contagious keeping in view the fact that the appropriate antibiotics have been administered. The antibiotic treatment generally last in 7-10 d but some cases of MRSA require longer treatment depending on the intensity and spectrum of infection [47].

The children recover well from SSSS but the left outward signs of SSSS appear bad and healing of skin lesions completes within 5-7 days of initial treatment.

OUTBREAKS OF SSSS

The SSSS is not a very common disease throughout world. The first noticed outbreak of SSSS was in Ireland. In available literatures related with SSSS, a small number of outbreaks have been observed [48]. However, infections associated with S. aureus are increasing. From maternity and neonatal perspective, the staphylococcus infection (both methicillin-sensitive and resistant) is a matter of concern.

In one recent study, a massive outbreak of the SSSS with an unusual phage pattern was recorded during a 115-day period and study involved 68 neonates. The exfoliative dermatitis was observed in 24 neonates, and bacterial strains were isolated from 23 neonates. Eight babies had generalized staphylococcal scarlet fever [49]. Therefore, chance of outbreaks may not be neglected and especially in neonatal sections, it may be difficult to control. In case of outbreak of SSSS, either in neonatal care unit or at children caring centre, the possibility of a staphylococcal carrier in the nearby area should be screened. In order to manage the problem associated with outbreak of SSSS, the healthcare personnel, nursing care staff or visitors or infected persons with S aureus should be identified. Upon identification of such persons, appropriate eradication medicines are to be given [48, 49]. To avoid any further infections, the concerned should follow strict hand washing with antibacterial soap [50].

COMPLICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH SSSS

The danger of SSSS lies in the fact that a different type of bacteria may invade some areas of the skin and may culminate complicated blood stream infection [51]. Loss of body fluid occurs when skin peels away, and the residual layer dries out; fluid loss is a critical issue at this time. As always, good hygiene can prevent the bacteria. In case of an outbreak, the nasal smears of neonates and staff associated should be examined. Improperly treated infections get worse. In SSSS, continous loss of fluid causing dehydration may worse the condition. Other complications include poor temperature control in young infants, septicemia (blood stream infection), Hair follicle infections including Staphylococcal folliculitis, boils, dermatitis, scabies, diabetic ulcers [52, 53].

Cellulitis

It occurs upon spreading of infection to a deeper layer of skin. It produces symptoms including reddish and inflamed skin with pain. The situation can usually be corrected with antibiotics and analgesics to reduce the pain.

Guttate psoriasis

In this, skin is noninfectious which may develop in teenagers after a bacterial infection but it occurs after a generalized throat infection. In this psoriasis, small, red, droplet-shaped, scaly patches are observed on the chest, arms and scalp. Antibacterial creams are applied on topical surface to control the symptoms and in some cases; the condition gets better even after 6-7 days.

Septicaemia

Septicaemia is a kind of bacterial infection of the blood. It causes diarrhea, cold, clammy skin, fever, vomiting, hypotension, confusion, faint feeling, dizziness and loss of consciousness [54].

Scarring

In rare cases, impetigo turns to scars. Scarring is considered as result of scratching at blisters, or sores. In general, the blisters and crusts do not leave a scar if left to be healed. The mark produced due to blisters disappears. The redness gradually diminishes varying from few days to few weeks.

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSG)

It is an infection associated with small blood vessels in the kidneys. The symptoms of PSG are reddish-brown color of urine, abdominal swelling (tummy) and ankles, hematourea, reduced amount of urine. Patients suffering from PSG require immediate medical treatment and their blood pressure should be monitored carefully. PSG can be fatal in adults, but the cases of children are very rare.

PREVENTION OF SSSS

In order to prevent SSSS, several facts are to be considered which includes following points [55]:

Antibacterial/ antiseptic soap are to be used in hand wash.

Clean towel or fresh clothing are to be used to dry the body or hands.

The linens and clothes are to be washed in hot water.

Antibacterial products are to be used in cleaning wall.

The fingernails must be short to avoid any contamination.

Schools and childcare centers are to be avoided when the infection is in contagious form.

The personal hygiene items should not be shared.

Washing hands before touching any damaged or broken skin.

In cases of mild infections, bacterial colonizing can be prevented in the nostril and under the fingernails with antibiotic creams like Fusidic Acid or by using petroleum jelly several times daily, for a week of each month.

FUTURE PRESPECTIVE IN SSSS

Progress in our understanding of SSSS is improving at an exciting end. The toxins for the exfoliation in SSSS have been identified, characterized and their structure elucidated. More recently, the epidermal target has been identified and this has explored an exciting avenue for further research [56, 57]. Particularly, by analyzing the 3D structure of the complex of exfoliative toxins desmoglein-1, structural biologists should be able to confirm their speculated mode of action. Recently, research on SSSS involved injecting exfoliative toxin into live new born animals. At present, this process can be repeated in the lab by the toxin incubation with desmoglein-1 and measuring degradation of the latter. This type of simple and quick assay can be used to compare difference in properties of the various toxin serotypes. In particular, it may explain how ETC and S. hyicus exfoliative toxin A are able to induce exfoliation without conserving the serine-histidine-aspartate active site. In addition, site-directed mutagenesis can be used to produce mutant toxins to understand the properties of the toxins, such as their species specificity and their unique enzymatic and superantigenic activities. Differences in the amino acid sequence or the 3D structure of desmoglein-1could explain the species specificity of the different toxin serotypes, while desmoglein-1polymorphism may explain why only a small proportion of individuals who are exposed to exfoliative toxins develop the disease.

The possibility of new avenue in the field of SSSS include investigation and application of rapid, specific and sensitive diagnostic tests using desmoglein-1 as antigen for quantification of toxin in plasma or other biological fluids taken from suspected persons of SSSS. The future prospect includes synthesis of analoges of the toxin-binding regions of desmoglein-1 to inhibit the toxins and therefore, prevent exfoliation, in the similar pattern as it has been shown with L. monocytogenes, whose ability to invade epithelial cells and it can be inhibited by N-terminal fragments and recombinant proteins of E cadherin (CDH-1 gene) [58]. Most of the pediatric cases of SSSS get well with antibiotics and supportive care, treatment with desmoglein-1analogues could be used for high risk cases such as adults with underlying diseases, children with extensive disease and immunocompromised patients. Such treatment may also be life saving in cases due to multidrug resistant S. aureus, where antibiotic treatment itself is not sufficient. A better understanding of the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins should also culminate to develop wide and more exciting applications. The better understanding of mechanism may be used by dermatologists to induce localised exfoliation to remove superficial skin lesions. Additionally, the binding site of desmoglein-1 of the toxins could be used to stabilise. This may protect the protein from destruction. Similarly, the targeting domain of the toxins which gives them such a specific site of action could be used to deliver drugs, such as chemotherapy, to a localized region within the epidermis. Another area that requires further research involves identification of factors that lead to development of the disease. In general, 1/3 population carries S. aureus commensally and out of total bacterial percentage, around 5% of these strains produce exfoliative toxin but only small proportion develop SSSS and generalized exfoliation. It is also possible that a triggering factor in either the organism or the host may be needed to produce the toxin, or the bacterial strain may continuously producing the toxins but the toxins would be prevented from reaching the epidermis, either locally on skin surface or in the blood.

The toxins released from bacterial strain crosss the mucous layer and endothelium of blood vessels. The mechanism of this fact needs to be investigated. Researchers have studied about the staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome toxin-1and enterotoxins A and B which is essential for crossing the gut layer. A synthetic peptide based has also been identified which is able to significantly reduce transcytosis [59]. The exfoliative toxins may serve as target for development of vaccines in future to eradicate SSSS.

CONCLUSION

SSSS is a critical syndrome in which acute exfoliation of the skin occurs followed by erythematous cellulitis. The main causative agent behind the fact is exfoliative toxins of S. aureus. Most of the cases of SSSS are cured absolutelly, specially when treatment starts in a very early stage of disease. Upon complete cure, Any visible difference or lasting marks to the skin surface does not appear. SSSS is treated with oral antibiotics (may be given by i.v. in severe cases). The area of skin surface requires cleansing and dressings with antiseptic cream. Emergency medical treatment is required in condition of imbalance fluid or salt.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to express sincere gratitude towards Dr. R. M. Dubey, Vice Chancellor, IFTM University, Moradabad for providing necessary help for the treatment of SSSS to Ms Arunima and ultimate library facility in the University for literature survey.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Itani O., Crump R., Mimouni F., et al. Picture of the month: SSSS. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1992;146:425–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conway D.G., Lyon R.F., Heiner J.D. A desquamating rash; staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013;61(1):118–119, 129. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubiche T., Bes M., Roudiere L., Langlaude F., Etienne J., Del Giudice P. Mild staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: an underdiagnosed clinical disorder. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166(1):213–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sah P., Rijal K.R., Shakya B., Tiwari B.R., Ghimire P. Nasal carriage Rate of Staphylococcus aureus in hospital personnel of National Medical College and Teaching Hospital and their susceptibility pattern. J Health Appl Sci. 2013;3:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farroha A., Frew Q., Jabir S., Dziewulski P. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome due to burn wound infection. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 2012;25(3):140–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanakawa Y., Stanley J.R. Mechanisms of blister formation by staphylococcal toxins. J. Biochem. 2004;136(6):747–750. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladhani S. Understanding the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003;39(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubiche T., Bes M., Roudiere L., Langlaude F., Etienne J., Del Giudice P. Mild staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: an underdiagnosed clinical disorder. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166(1):213–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto T., Nishiyama A., Takano T., Yabe S., Higuchi W., Razvina O., Shi D. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: community transmission, pathogenesis, and drug resistance. J. Infect. Chemother. 2010;16(4):225–254. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acharya K.R., Passalacqua E.F., Jones E.Y., Harlos K., Stuart D.I., Brehm R.D., Tranter H.S. Structural basis of superantigen action inferred from crystal structure of toxic-shock syndrome toxin-1. Nature. 1994;367(6458):94–97. doi: 10.1038/367094a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alouf J.E., Müller-Alouf H. Staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigens: molecular, biological and clinical aspects. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;292(7-8):429–440. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adesiyun A.A., Lenz W., Schaal K.P. Exfoliative toxin production by Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from animals and human beings in Nigeria. Microbiologica. 1991;14(4):357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiedemann K., Schmid C., Hamm H., Wirbelauer J. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in a very low birth weight premature infant. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2016;220(1):35–38. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1559653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhakdi S., Tranum-Jensen J. Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Rev. 1991;55(4):733–751. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.733-751.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lina G., Piémont Y., Godail-Gamot F., Bes M., Peter M.O., Gauduchon V., Vandenesch F., Etienne J. Involvement of panton-valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;29(5):1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluytmans J., van Belkum A., Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10(3):505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koufakis T., Gabranis I., Karanikas K. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an adult, immunocompetent patient. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;19(2):228–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bitar C.M., Mayhall C.G., Lamb V.A., Bradshaw T.J., Spadora A.C., Dalton H.P. Outbreak due to methicillin- and rifampin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and eradication of the resistant strain from the hospital. Infect. Control. 1987;8(1):15–23. doi: 10.1017/S0195941700066935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez-Truque N., Tedeschi S., Saye E.J., McKenna B.D., Langdon W., Wright J.P., Alsentzer A., Arnold S., Saville B.R., Wang W., Thomsen I., Creech C.B. Relationship between maternal and neonatal Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1252–e1259. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aydin D., Alsbjørn B. Severe case of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in a 5-year-old child - case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2016;4(4):416–419. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz R.A., McDonough P.H., Lee B.W. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013;69(2):187.e1–187.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arbuthnott J.P., Kent J., Lyell A., et al. Studies of staphylococcal toxins in relation to toxic epidermal necrolysis (the scalded skin syndrome). Br J Derm. 1972;86:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb15412.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey C.J., de Azavedo J., Arbuthnott J.P. A comparative study of two serotypes of epidermolytic toxin from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1980;624(1):111–120. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey C.J., Lockhart B.P., Redpath M.B., Smith T.P. The epidermolytic (exfoliative) toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berl.) 1995;184(2):53–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00221387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cribier B., Piemont Y., Grosshans E. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in adults. A clinical review illustrated with a new case. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994;30(2 Pt 2):319–324. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss C., Gupta E. The Nikolsky sign in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child. 1998;79(3):290–293. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira AR, Aires S, Faria C, Santos E. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009478. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handler M.Z., Schwartz R.A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014;28(11):1418–1423. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machida K. Immunological investigations on pathogenesis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Rinsho Byori. 1995;43(6):547–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falk D.K., King L.E., Jr Criteria for the diagnosis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in adults. Cutis. 1983;31(4):421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curran J.P., Al-Salihi F.L. Neonatal staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: massive outbreak due to an unusual phage type. Pediatrics. 1980;66(2):285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Azavedo J.C., Arbuthnott J.P. Assays for epidermolytic toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Methods Enzymol. 1988;165:333–338. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(88)65049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehrotra M., Wang G., Johnson W.M. Multiplex PCR for detection of genes for Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1, and methicillin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000;38(3):1032–1035. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1032-1035.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladhani S., Evans R.W. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child. 1998;78(1):85–88. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkin R.M., Newton D.A., Swift J.D. Pediatric hospital medicine: Textbook of inpatient management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel N.N., Patel D.N. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Am. J. Med. 2010;123(6):505–507. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porro A.M., Caetano Lde.V., Maehara Lde.S., Enokihara M.M. Non-classical forms of pemphigus: pemphigus herpetiformis, IgA pemphigus, paraneoplastic pemphigus and IgG/IgA pemphigus. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014;89(1):96–106. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Runswick S.K., O’Hare M.J., Jones L., Streuli C.H., Garrod D.R. Desmosomal adhesion regulates epithelial morphogenesis and cell positioning. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3(9):823–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishifuji K., Shimizu A., Ishiko A., Iwasaki T., Amagai M. Removal of amino-terminal extracellular domains of desmoglein 1 by staphylococcal exfoliative toxin is sufficient to initiate epidermal blister formation. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2010;59(3):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieg T, Bickers DR, Miyachi Y. Therapy of skin diseases: A worldwide perspective on therapeutic approaches and their molecular basis. London, New York: Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht; 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanakawa Y., Schechter N.M., Lin C., Garza L., Li H., Yamaguchi T., Fudaba Y., Nishifuji K., Sugai M., Amagai M., Stanley J.R. Molecular mechanisms of blister formation in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110(1):53–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amagai M., Matsuyoshi N., Wang Z.H., Andl C., Stanley J.R. Toxin in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome targets desmoglein 1. Nat. Med. 2000;6(11):1275–1277. doi: 10.1038/81385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston G.A. Treatment of bullous impetigo and the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in infants. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2004;2(3):439–446. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel G.K. Treatment of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2004;2(4):575–587. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handler M.Z., Schwartz R.A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014;28(11):1418–1423. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kouakou K., Dainguy M.E., Kassi K. Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome in Neonate. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2015;4 doi: 10.1155/2015/901968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevens D.L., Ma Y., Salmi D.B., McIndoo E., Wallace R.J., Bryant A.E. Impact of antibiotics on expression of virulence-associated exotoxin genes in methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195(2):202–211. doi: 10.1086/510396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El Helali N., Carbonne A., Naas T., Kerneis S., Fresco O., Giovangrandi Y., Fortineau N., Nordmann P., Astagneau P. Nosocomial outbreak of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: epidemiological investigation and control. J. Hosp. Infect. 2005;61(2):130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curran J.P., Al-Salihi F.L. Neonatal staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: massive outbreak due to an unusual phage type. Pediatrics. 1980;66(2):285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dancer S.J., Simmons N.A., Poston S.M., Noble W.C. Outbreak of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome among neonates. J. Infect. 1988;16(1):87–103. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(88)96249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lina G., Vandenesch F., Etienne J., Data from the National Center for Staphylococcal Toxemia Staphylococcal and streptococcal pediatric toxic syndrome from 1998 to 2000. Arch. Pediatr. 2001;8(Suppl. 4):769s–775s. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(01)80195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Complications of impetigo. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Impetigo/Pages/Complications.aspx. [Accessed February 10, 2016].

- 53.Hoffmann R., Lohner M., Böhm N., Schaefer H.E., Leititis J. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) and consecutive septicaemia in a preterm infant. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1994;190(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staphylococcal skin infections. Available at: http://www.dermnetnz.org/bacterial/staphylococci.html. [Accessed February 10, 2016].

- 55.Kapral F.A. Staphylococcus aureus: some host-parasite interactions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1974;236(0):267–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb41497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ladhani S. Recent developments in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2001;7(6):301–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.da Silva Tatley F., Aldwell F.E., Dunbier A.K., Guilford P.J. N-terminal E-cadherin peptides act as decoy receptors for Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 2003;71(3):1580–1583. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1580-1583.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lecuit M., Dramsi S., Gottardi C., Fedor-Chaiken M., Gumbiner B., Cossart P. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity towards the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 1999;18(14):3956–3963. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shupp J.W., Jett M., Pontzer C.H. Identification of a transcytosis epitope on staphylococcal enterotoxins. Infect. Immun. 2002;70(4):2178–2186. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2178-2186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]