Abstract

Background

Patients with coronary heart disease undergo cardiac rehabilitation in order to reduce their cardiovascular risk factors. Often, however, the benefit of rehabilitation is lost over time. It is unclear whether this happens in the same way to men and women. We studied whether the setting of gender-specific behavior goals with an agreement between the doctor and the patient at the end of rehabilitation can prolong its positive effects.

Methods

This study was performed with a mixed-method design. It consisted of qualitative interviews and group discussions with patients, doctors and other treating personnel, and researchers, as well as a quantitative, randomized, controlled intervention trial in which data were acquired at four time points (the beginning and end of rehabilitation and then 6 and 12 months later). 545 patients, 262 of them women (48.1%), were included. The patients were assigned to a goal checking group (n = 132), a goal setting group (n = 143), and a control group (n = 270). The primary endpoints were health-related behavior (exercise, diet, tobacco consumption), subjective state of health, and medication adherence. The secondary endpoints included physiological protection and risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol (HDL, LDL, and total), blood sugar, HbA1c, and body-mass index.

Results

The intervention had no demonstrable effect on the primary or secondary endpoints. The percentage of smokers declined to a similar extent in all groups from the beginning of rehabilitation to 12 months after its end (overall figures: 12.4% to 8.6%, p <0.05). The patients’ exercise behavior, diet, and subjective state of health also improved over the entire course of the study. Women had a healthier diet than men. Subgroup analyses indicated a possible effect of the intervention on exercise behavior in women who were employed and in men who were not (p<0.01).

Conclusion

The efficacy of goal setting was not demonstrated. Therefore, no indication for its routine provision can be derived from the study results.

Disorders of the cardiovascular system continue to be the most common cause of death in Germany. Among deaths from all causes, the proportion of cardiovascular disorders was 38.9% in 2014, with coronary heart disease being the most important specific cause of death (1).

Measures taken in secondary prevention that aim to prevent a further coronary event after successful therapy are of fundamental importance, among others. It is well known that cardiovascular risk factors decrease in the context of subsequent curative treatment (phase II) (2, 3). However, these positive effects often disappear in phase III of rehabilitation, which comprises lifelong follow-up care delivered in patients’ places of residence. In order to ensure the sustained effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation measures, long-term aftercare programs are suitable, which in recent years have been undertaken on the basis of various different concepts. These programs primarily aim to stabilize physical performance and reduce behavior-related risk factors (such as smoking) (4– 13).

Setting goals may be a useful tool for stabilizing health-promoting behaviors; this has not become established to a satisfactory degree in routine rehabilitation practice, and little is known about its effectiveness. Furthermore, a substantial need exists for studies investigating which gender-specific elements may have a secondary preventive benefit for patients undergoing rehabilitation (14).

We aimed to develop, implement, and evaluate an intervention in which the patient undergoing rehabilitation and their doctor agree on goals in terms of behavioral (physical activity, diet, tobacco consumption) and physiological (hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, body weight) risk factors and protection factors at the end of the rehabilitation measure and follow this up three months later. The primary endpoints were behaviors related to physical activity and diet/nutrition, tobacco consumption, subjective state of health, and medication adherence. As our secondary result parameters, we collected data on physiological protection factors and risk factors (systolic and diastolic blood pressure; total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol concentrations; blood glucose levels; HbA1c; and body mass index). We explored gender-specific ideas of goals and studied the effect of agreed goals on health behaviors and risk profiles.

Methods

We used a mixed methods study design (15). In the qualitative study phase, guideline-based interviews and group discussions with patients and medical experts were conducted in order to identify personal goal statements. In order to test the hypothesis of whether goal setting has a positive effect on health behaviors, we subsequently conducted a randomized controlled intervention study with four measurement dates (start [T1] and end [T2], as well as 6 [T3] and 12 [T4] months after the end of the rehabilitation measure). 545 patients were included (of whom 48.1% were female); these were randomly allocated to three study arms: the goal checking group IGa (n = 132), where the investigators conducted a goal setting interview with the patients at the end of the rehabilitation measure and a goal checking interview 3 months after its end; the goal setting group IGb (n = 143), where the goal setting talk took place at the end of the rehabilitation measure; and the control group CG (n = 270), in which patients received routine treatment (Figure 1). The methods are described in detail in the eSupplement.

Figure 1.

Study design (quantitative study phase)

IG, intervention group; CG, control group

The study (CARO-PRE II) gained approval from the ethics committee at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA1/056/11) and was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00003568). The study period ran from January 2011 to December 2014.

The primary endpoints were defined as change in physical activity, dietary habits, tobacco consumption, subjective state of health, and medication adherence over time. Physical activity was operationalized by using the data collection instrument by Singer and Wagner (16) and dietary habits by using the food frequency list by Winkler and Döring (17). In order to assess participants’ current subjective state of health, we used the visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which is a part of the EuroQol questionnaire (18). The Morisky score (19) was used to document medication intake behaviors (medication adherence). In order to capture smoking behaviors, patients’ current status (smoker/non-smoker) was recorded.

We developed an intervention consisting of the following elements:

Goal setting at the end of the rehabilitation measure: patient and doctor set out and record goals for behavior-related protection factors and risk factors.

Goal checking three months after the end of the rehabilitation measure: reflecting on goal adherence and offering support if practical implementation caused difficulty.

Information brochure for patients, which contained disorder-specific information.

Patient passport to document the measured values for the physiological protection factors and risk factors.

Instruction manual for doctors on standardized interviewing for goal setting and goal checking.

The three study groups were analyzed by using latent change models with regard to the described endpoints (20). The significance level for the primary endpoints was defined as α = 0.01 after Bonferroni correction for multiple statistical tests.

Results

Qualitative study phase

The evaluation of the interviews conducted with 20 rehabilitation patients showed that men and women were not fundamentally different in the total number of behavioral goals set (with a mean of 7 goals each). However, the substance of the goals they named for the time after the rehabilitation therapy differed.

Male rehabilitation patients set themselves goals mainly in the area of physical activity (56%), followed by goals within their careers (18%) and diet/nutrition (16%). Female patients named only half as many goals in the context of physical activity as male patients. In addition to physical activity (27%), changing their dietary habits was the second most important goal for women (25%), followed by goals relating to their careers (22%). Two months after the end of the rehabilitation measure, women had realized 74% of their goals and men 57% (21). The analysis of the interviews with experts and patients implied a need for support for women with regard to physical activity and for men with regard to a healthier diet/nutrition.

Quantitative study phase

Baseline analyses—545 patients were included in the analysis of the baseline data; 283 (51.9%) of these were men and 262 (48.1%) women. 309 (56.7%) of patients were treated in inpatient rehabilitation centers and 236 (43.3%) in outpatient centers. Table 1 shows relevant sociodemographic, disorder related, and behavior related patient characteristics in the three study groups. No significant differences existed in the groups for all variables under study. The three study arms can therefore be regarded as balanced. Table 2 compares the sexes regarding their health behaviors and state of health as well as physiological protection factors and risk factors. Women followed a healthier diet, smoked less, and perceived their state of health as worse than did men. Measured concentrations for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol in women were higher than in men.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (T1) of the study groups.

| Variable | Intervention IGa | Intervention IGb | Control group | Statistical test and p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (±SD) | 61.45 (10.99) | 60.87 (10.54) | 61.17 (10.31) | ANOVA, p=0.90 |

| Gender % (n) | ||||

| Female | 47.0 (62) | 49.0 (70) | 48.1 (130) | χ 2, p=0.95 |

| Male | 53.0 (70) | 51.0 (73) | 51.9 (140) | |

| Professional position % (n) | ||||

| Blue-collar worker | 18.3 (20) | 22.5 (27) | 24.9 (56) | χ 2, p=0.54 |

| White-collar worker/civil servant | 65.1 (71) | 66.7 (80) | 62.7 (141) | |

| Self-employed/other | 16.5 (18) | 10.8 (13) | 12.4 (28) | |

| Working status % (n) | ||||

| Full time | 32.0 (40) | 45.2 (57) | 33.6 (87) | χ 2, p=0.37 |

| Part time | 11.2 (14) | 9.5 (12) | 9.7 (25) | |

| Retired, disability pension | 46.4 (58) | 37.3 (47) | 46.7 (121) | |

| Unemployed, homemaker | 10.4 (13) | 7.9 (10) | 10.0 (26) | |

| Setting of rehabilitation measure % (n) | ||||

| Outpatient measure | 43.9 (58) | 41.3 (59) | 44.1 (119) | χ 2, p=0.85 |

| Inpatient measure | 56.1 (74) | 58.7 (84) | 55.9 (151) | |

| Cardiac measure % (n) | ||||

| PTCA/PCI | 65.2 (86) | 67.1 (96) | 64.2 (172) | χ 2, p=0.87 |

| Bypass surgery | 27.3 (36) | 23.8 (34) | 25.4 (68) | |

| None (general medical measure) | 7.6 (10) | 9.1 (13) | 10.4 (28) | |

| Physical activity, mean (±SD) | ||||

| Working/employed | 2.77 (0.54) | 2.77 (0.54) | 2.84 (0.41) | ANOVA, p=0.63 |

| Not working/not employed | 2.82 (0.63) | 2.84 (0.61) | 2.92 (0.57) | ANOVA, p=0.32 |

| Dietary/nutritional behavior, mean (±SD) | 26.58 (5.75) | 26.36 (5.19) | 26.44 (5.63) | ANOVA, p=0.96 |

| Smoking status % (n) | ||||

| Smoker | 12.5 (16) | 10.7 (15) | 13.3 (35) | χ 2, p=0.51 |

| Former smoker | 47.7 (61) | 48.6 (68) | 53.8 (142) | |

| Never smoker | 39.8 (51) | 40.7 (57) | 33.0 (87) | |

| Subjective state of health, mean (±SD) | 58.55 (18.54) | 57.24 (20.62) | 59.97 (18.11) | ANOVA, p=0.39 |

| Physiological protection factors and risk factors, mean (±SD) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHG) | 126.63 (21.09) | 126.03 (19.93) | 127.99 (19.85) | ANOVA, p=0.61 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHG) | 76.02 (12.43) | 76.75 (11.13) | 78.14 (11.91) | ANOVA, p=0.20 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 180.59 (40.22) | 177.31 (38.15) | 177.30 (42.12) | ANOVA, p=0.74 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 108.94 (34.39) | 103.63 (30.36) | 105.41 (33.95) | ANOVA, p=0.41 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 47.50 (13.74) | 48.70 (17.55) | 47.54 (13.30) | ANOVA, p=0.73 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 106.38 (31.33) | 105.59 (38.88) | 105.68 (31.53) | ANOVA, p=0.98 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.53 (1.57) | 6.39 (1.75) | 6.50 (1.59) | ANOVA, p=0.89 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 28.06 (4.58) | 28.26 (5.00) | 28.03 (4.77) | ANOVA, p=0.89 |

IGa, goal checking group; IGb, goal setting group; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation

Table 2. Baseline characteristics (T1) – gender-specific comparison of health behaviors, state of health, and protection and risk factors.

| Variable | Gender | Statistical test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Physical activity, mean (±SD) | ||||

| Working | 2.77 (0.47) | 2.84 (0.52) | ANOVA | 0.39 |

| Not working | 2.85 (0.60) | 2.90 (0.59) | ANOVA | 0.40 |

| Dietary/nutritional behavior, mean (±SD) | 24.71 (5.28) | 28.48 (5.13) | ANOVA | <0.01 |

| Smoking status % (n) | ||||

| Smoker | 66.7 (44) | 33.3 (22) | ||

| Former smoker | 58.3 (158) | 41.7 (113) | χ 2 | <0.01 |

| Never smoker | 38.5 (75) | 61.5 (120) | ||

| Subjective state of health, mean (±SD) | 61.00 (19.23) | 56.55 (18.27) | ANOVA | <0.01 |

| Physiological protection and risk factors, mean (±SD) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHG) | 126.28 (18.53) | 128.08 (21.78) | ANOVA | 0.30 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHG) | 77.24 (10.71) | 77.29 (13.00) | ANOVA | 0.96 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 171.07 (37.19) | 185.83 (42.85) | ANOVA | <0.01 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 102.32 (29.74) | 109.62 (36.21) | ANOVA | 0.01 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 42.48 (11.04) | 53.65 (15.72) | ANOVA | <0.01 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 106.48 (35.35) | 105.13 (31.49) | ANOVA | 0.65 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.44 (1.49) | 6.53 (1.74) | ANOVA | 0.66 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 28.18 (4.19) | 28.01 (5.34) | ANOVA | 0.69 |

SD, standard deviation

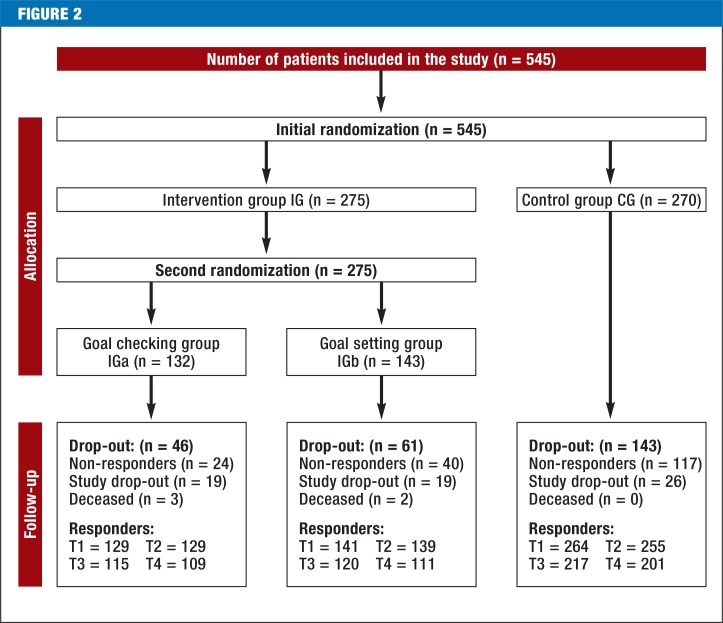

Response rate—The response rate for the questionnaires was 98% (n = 534) at T1, 96% (n = 523) at T2, 82.9% (n = 452) at T3, and 77.2% (n = 421) at T4. No important differences were seen in terms of which study arm dropped-out participants came from (p = 0.19). Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the study.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants through the study

Follow-up analyses—For the primary endpoints physical activity (exercise behavior), dietary/nutritional habits, current subjective state of health, and medication adherence, no effects were found for the intervention (Table 3, eTable 1). Regarding changes to smoking status, no model calculations were possible owing to the low number of smokers; for this reason, relevant conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention cannot be drawn with regard to smoking.

Table 3. Primary endpoints (exercise behavior, dietary/nutritional behavior, state of health, medication adherence) by study groups*1.

| Variable | Intervention IGa | InterventionIGb | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise behavior, mean (p-value) | |||

| Start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | 2.82 (0.08) | 2.89 (0.50) | 2.94 |

| 12 months after rehabilitation (T4) | 3.09 (0.09) | 3.10 (0.37) | 3.10 |

| Dietary/nutritional behavior, mean (p-value) | |||

| Start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | 27.80 (0.95) | 27.93 (0.87) | 27.84 |

| 12 months after rehabilitation (T4) | 30.08 (0.65) | 30.11 (0.77) | 29.86 |

| Subjective state of health, mean (p-value) | |||

| Start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | 57.37 (0.55) | 55.82 (0.16) | 58.61 |

| 12 months after rehabilitation (T4) | 73.09 (0.11) | 71.51 (0.11) | 70.85 |

| Medication adherence*2, mean (p-value) | |||

| 6 months after rehabilitation (T3) | 0.15 (0.39) | 0.24 (0.67) | 0.18 |

| 12 months after rehabilitation (T4) | 0.22 (0.27) | 0.30 (0.31) | 0.17 |

Based on latent change models adjusted for age, gender, and participation in heart groups

(detailed data are shown in eTable 1).

Score ranges: exercise behavior (1–5 points, high score: good).

Dietary/nutritional behavior (0–48, high score: good).

Health status (0–100, high score: good).

Medication adherence (0–4, low score: good)

*1The primary endpoint tobacco consumption was not analyzed by study groups because case numbers were too small.

*2Medication adherence was recorded only at T3 and T4.

IGa, goal checking group; IGb, goal setting group

eTable 1. Primary endpoints (exercise behavior, dietary/nutritional behavior, state of health, medication adherence) by study groups*1.

| Variable | Exercise behavior | Dietary/nutritional behavior | Subjective state of health | Medication adherence*2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se(b) | p-value | b | se(b) | p-value | b | se(b) | p-value | b | se(b) | p-value | |

| Status at start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | Status at T3 | |||||||||||

| (R2=0.018) | (R2=0.208) | (R2=0.030) | (R2=0.021) | |||||||||

| Constant | 2.937 | 0.056 | <0.001 | 27.844 | 0.472 | <0.001 | 58.607 | 1.664 | <0.001 | 0.176 | 0.054 | 0.001 |

| IGa | −0.117 | 0.066 | 0.076 | −0.039 | 0.576 | 0.946 | −1.239 | 2.050 | 0.546 | 0.056 | 0.065 | 0.390 |

| IGb | −0.045 | 0.066 | 0.498 | 0.093 | 0.555 | 0.867 | −2.793 | 1.980 | 0.158 | −0.027 | 0.064 | 0.671 |

| Change from start of rehabilitation (T1) to 6 months after end of rehabilitation (T3) | Change T3 to T4 | |||||||||||

| (R2=0.042) | (R2=0.061) | (R2=0.013) | (R2=0.010) | |||||||||

| Constant | 0.084 | 0.052 | 0.108 | 1.886 | 0.454 | <0.001 | 10.711 | 1.790 | <0.001 | −0.009 | 0.057 | 0.877 |

| IGa | 0.079 | 0.061 | 0.199 | 0.097 | 0.555 | 0.862 | 2.104 | 2.215 | 0.342 | 0.074 | 0.067 | 0.273 |

| IGb | −0.017 | 0.061 | 0.784 | −0.001 | 0.538 | 0.999 | 3.948 | 2.147 | 0.066 | 0.069 | 0.067 | 0.307 |

| Change from start of rehabilitation (T1) to 12 months after end of rehabilitation (T4) | ||||||||||||

| (R2=0.02) | (R2=0.074) | (R2=0.02) | ||||||||||

| Constant | 0.163 | 0.054 | 0.003 | 2.017 | 0.474 | <0.001 | 12.242 | 1.787 | <0.001 | |||

| IGa | 0.105 | 0.061 | 0.089 | 0.262 | 0.574 | 0.648 | 3.479 | 2.195 | 0.113 | |||

| IGb | 0.054 | 0.061 | 0.373 | 0.163 | 0.561 | 0.772 | 3.445 | 2.134 | 0.107 | |||

Latent change models (n=545) adjusted by age, sex, and heart group participation

Score ranges: exercise behavior (1–5 points, high score: good). dietary/nutritional behavior (0–48, high score: good),

health (0–100, high score: good), medication adherence (0–4, low score: good)

*1The primary endpoint tobacco consumption was not analyzed by study groups because case numbers were too low.

*2Medication adherence was recorded only at T3 and T4.

b, regression coefficient; se(b), standard error of b

IGa, goal checking group; IGb, goal setting group

Exercise behavior in everyday life increased over the entire observation period in all study groups.

Dietary/nutritional habits and subjective state of health also improved over the entire study period and in all three study arms. For medication adherence, no substantial change was seen in the study groups between T3 and T4.

The proportion of smokers fell across groups from 12.4% (n = 66) at T1 to 8.6% (n = 36) at T4 (χ 2=5.74, p = 0.017, df = 1) (data not shown).

Similarly, no effects were observed for the intervention for the secondary endpoints (blood pressure; blood glucose; total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol; HbA1c; and body mass index) over the study period.

Total cholesterol concentrations fell significantly in all study groups during the period of the rehabilitation measure (from T1 to T2) (p<0.001). They rose after the rehabilitation measure had ended, but they remained below the baseline measurement at T1. Crucial differences between the sexes were seen for the development of total cholesterol (χ 2= 41.09, p<0.001, df = 12). These resulted mainly from the higher values in women that already existed at T1. LDL cholesterol also fell in all study groups during the rehabilitation program (p<0.001). Subsequently LDL levels rose again but at T4 remained below the level at T1. HDL cholesterol concentrations rose in all study arms after the end of the rehabilitation measure. At T4 they were significantly above the baseline level (p<0.001). Differences between the sexes reached significance (χ 2= 104.54, p<0.001, df = 12). HDL values in women were higher than in men at all measuring points and resulted from the higher baseline level in women (data not shown).

Subgroup analyses—The comparison between the sexes with regard to the primary endpoints showed gender-specific differences in the subgroup analyses. In women in employment (n = 100) there were indications that the intervention potentially affected their physical activity if they had participated in a heart group. Furthermore, women in IGb displayed improved behavior regarding physical activity in everyday life at T4 (eTable 2). In non-working men, we saw indications of improved behaviors in terms of physical exercise at T4 (IGa and IGb) (eTable 3).

eTable 2. Exercise behavior of rehabilitation patients in employment, grouped by gender.

| Variable | Female (n=100) | Male (n=163) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se(b) | p-value | b | se(b) | p-value | |

| State at start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | ||||||

| (R2=0.208) | (R2=0.016) | |||||

| Constant | 3.038 | 0.137 | <0.001 | 2.732 | 0.085 | <0.001 |

| IGa | −0.064 | 0.158 | 0.688 | −0.031 | 0.107 | 0.772 |

| IGb | −0.152 | 0.136 | 0.264 | −0.016 | 0.105 | 0.883 |

| Change from start of rehabilitation measure (T1) to 6 months after end of rehabilitation measure (T3) | ||||||

| (R2=0.31) | (R2=0.032) | |||||

| Constant | −0.090 | 0.087 | 0.299 | 0.091 | 0.077 | 0.237 |

| IGa | −0.047 | 0.116 | 0.683 | 0.027 | 0.104 | 0.792 |

| IGb | 0.147 | 0.090 | 0.102 | 0.058 | 0.101 | 0.565 |

| HG drop-out | 0.095 | 0.147 | 0.520 | –0.015 | 0.136 | 0.913 |

| HG participation | 0.305 | 0.090 | 0.001 | 0.087 | 0.095 | 0.362 |

| Change from start of rehabilitation measure (T1) to 12 months after end of rehabilitation measure (T4) | ||||||

| (R2=0.342) | (R2=0.012) | |||||

| Constant | −0.125 | 0.092 | 0.172 | 0.191 | 0.076 | 0.012 |

| IGa | 0.170 | 0.154 | 0.269 | −0.028 | 0.094 | 0.765 |

| IGb | 0.272 | 0.095 | 0.004 | −0.032 | 0.095 | 0.732 |

| HG drop-out | 0.066 | 0.160 | 0.679 | −0.016 | 0.121 | 0.895 |

| HG participation | 0.246 | 0.097 | 0.011 | 0.066 | 0.085 | 0.441 |

Latent change-models adjusted by age and gender.

b, Regression coefficient; se(b), standard error of b; HG, heart group; IGa, goal checking group; IGb, goal setting group.

Significant p-values are in bold type

eTable 3. Exercise behavior of non-employed rehabilitation patients grouped by gender.

| Variable | Female (n=137) | Male (n=107) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se(b) | p-value | b | se(b) | p-value | |

| Status at start of rehabilitation measure (T1) | ||||||

| (R2=0.029) | (R2=0.113) | |||||

| Constant | 2.855 | 0.103 | <0.001 | 3.199 | 0.099 | <0.001 |

| IGa | −0.073 | 0.137 | 0.597 | −0.261 | 0.130 | 0.044 |

| IGb | 0.102 | 0.156 | 0.513 | −0.226 | 0.148 | 0.127 |

| Change from start (T1) to 6 months after end (T3) of rehabilitation | ||||||

| (R2=0.153) | (R2=0.12) | |||||

| Constant | 0.161 | 0.093 | 0.083 | −0.105 | 0.093 | 0.260 |

| IGa | 0.132 | 0.119 | 0.265 | 0.197 | 0.119 | 0.098 |

| IGb | −0.062 | 0.136 | 0.647 | −0.077 | 0.135 | 0.566 |

| HG drop-out | −0.553 | 0.512 | 0.280 | 0.272 | 0.159 | 0.087 |

| HG participation | 0.044 | 0.107 | 0.681 | 0.177 | 0.120 | 0.139 |

| Change from start (T1) to 12 months after end (T4) of rehabilitation | ||||||

| (R2=0.04) | (R2=0.458) | |||||

| Constant | 0.362 | 0.097 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.088 | 0.937 |

| IGa | 0.074 | 0.116 | 0.523 | 0.338 | 0.098 | <0.001 |

| IGb | 0.066 | 0.134 | 0.624 | 0.335 | 0.112 | 0.003 |

| HG drop-out | −0.000 | >1.000 | 1.000 | 0.226 | 0.110 | 0.041 |

| HG participation | −0.094 | 0.107 | 0.379 | 0.047 | 0.082 | 0.568 |

Latent change models adjusted for age and gender

b, regression coefficient; se(b), standard error of b; HG: heart group; IGa, goal checking group; IGb, goal setting group

Significant p-values are in bold type.

In terms of dietary habits, men and women differed clearly at all follow-up points (χ 2= 58.57, p<0.001, df = 9). Women followed better diets than men. In terms of subjective state of health and adherence to medication, no gender-specific differences were seen (χ 2= 8.95, p = 0.44, df = 9 and χ 2= 4.07, p = 0.67, df = 6, respectively) over time (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study investigated whether goal setting undertaken by rehabilitation patients with coronary heart disease and their treating physicians at the end of the rehabilitation measure had an effect on cardiac risk factors during phase III of the rehabilitation.

As far as the primary endpoints physical activity, diet/nutrition, tobacco consumption, subjective state of health, and medication adherence, as well as the secondary result parameters (physiological protection factors and risk factors) are concerned, no differences were confirmed between the three study groups. The risk factors lack of exercise, unhealthy diet/nutrition, and smoking improved over the entire time, but no benefit was confirmed for the actual intervention. The smoking rate across the study groups fell from 12.4% initially to 8.6% after a year.

Exploratory subgroup analyses showed indications of positive effects (some 0.3 points) regarding improved exercise behavior in everyday life. These effects are to be interpreted as slight (22). Especially women in employment were able to increase their physical activity. Furthermore, participation in a heart group had a positive effect on women’s exercise behavior. A gender-specific subgroup effect was also seen for non-working rehabilitation patients. Men improved their physical activity. The background of this observation may be that men who are not in employment strongly internalize the information provided about the importance of physical exercise during the goal setting and goal checking sessions and then proceed to put this into practice.

In recent years, numerous intervention measures have been conducted to reduce existing risk factors in phase III rehabilitation (4– 13). Self-regulation techniques—such as setting behavior-related goals, self control, time planning, and feedback techniques—provide valuable tools to this end (23– 25). In the present study, a complex approach was followed in order to set goals for behavioral and physiological protection factors and risk factors in the rehabilitation setting, document these in writing, and refresh them three months after the end of the rehabilitation measure. Special attention was given to the consideration of gender-specific aspects. Efficacy studies with a concept such as this have thus far not been described in the literature, and for this reason it is not possible to compare results. An international review article by Ferrier et al. (26) showed—at least for the area of physical activity—the effectiveness of a collaborative approach between therapist and cardiological rehabilitation patient, in which specific goals are set in a motivational interview. However, our study did not confirm this effect.

Limitations

In conducting the study, it was not possible in most institutions to use one doctor for participants in the intervention groups only and another in the control group. As the goal setting took place in the discharge consultation, treatment diffusion is a possibility, of which rehabilitation patients in the control group might have benefitted. The effects of the intervention measure are therefore rather likely to have been underestimated. Since the collection of interview data is based on self-reports from the rehabilitation patients, socially desirable responding behavior cannot be ruled out. This would, however, affect all three arms of the study and would therefore not systematically bias the results when comparing the groups. As in all intervention studies, it needs to be borne in mind that the calculation of case numbers was oriented exclusively to the primary endpoints. Analyses of secondary endpoints or subgroups are merely explorative and require affirmation in confirmatory studies. An additional limit is the fact that no data were collected regarding mortality or further cardiac events.

Conclusions

The efficacy of the intervention presented in this article, whereby goals were set jointly by doctors and patients at the end of a rehabilitation measure, and were refreshed three months later, was not shown in terms of the primary and secondary endpoints. The indications for a possibly beneficial effect on exercise behaviors among women in employment and non-employed men will have to be investigated in further studies. The implementation of this concept in routine clinical practice can therefore not be concluded from these results.

Supplementary Material

Sabine Stamm-Balderjahn, Martin Brünger, Anne Michel, Christa Bongarth, Karla Spyra

The present study used a mixed methods design (15). During the qualitative phase of the study, guideline-based interviews and group discussions were conducted with patients and medical experts, in order to identify specific expectations and cognitions (for example, ideas for goals) among male and female rehabilitation patients for sustained health behavior. We conducted a randomized controlled intervention study with four measuring points in order to test the hypothesis of whether goal setting has a positive effect on health behaviors.

Qualitative study phase

We conducted 40 interviews and four group discussions with patients, as well as eight expert interviews with scientists/academics and treating medical professionals. The guideline-based interviews were conducted by topic and were recorded with a digital audio recorder. After transcription of the audio files, the patient interviews were evaluated on the basis of an analysis of their content, following the flow model by Mayring (e1). By developing a differentiated system of categories, the previously defined elements from the text material were extracted and allocated. The aim is to reflect conceptual associations that represent general factors on a so called case structure level that go beyond the level of individual cases. The evaluation strategies of Meuser and Nagel (e2) were used to evaluate the expert interviews. The analysis consisted of five working steps, to be done in sequence, that aimed to extricate the common elements beyond the individual case from the interviews and to reduce the volume of data.

Quantitative study phase

Design

We conducted a randomized controlled intervention study with several measuring time points (start [T1] and end [T2], as well as 6 [T3] and 12 [T4] months after the end of the rehabilitation measure).

Participants and sample

40 patients (47.5% women) and 8 experts participated in the qualitative phase. 545 patients (48.1% women) from five outpatient and five inpatient rehabilitation centers in five federal states (Berlin, Bavaria, Hamburg, Hesse, and Saxony) were included in the intervention study; the inclusion criteria were: patients who had had an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or aorto-coronary venous bypass surgery (ACVB) and who were aged between 18 and 85 years.

Study participants were allocated to one of three study groups: a goal checking group IGa (n = 132), in which a goal setting interview was conducted with patients at the end of the rehabilitation measure and a goal checking interview three months after the end of the rehabilitation; a goal setting group IGb (n = 143), where a goal setting interview was conducted at the end of the rehabilitation measure; and a control group CG (n = 270), in which patients received routine treatment. The initial randomization took place at the onset of the rehabilitation measure; patients were allocated either to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG). The second randomization took place at the end of the rehabilitation measure; the patients in IG were allocated either to the goal checking group IGa or the goal setting group IGb (Figure 1).

Ethics approval and data protection

Ethics approval was granted by the ethics committee at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA1/056/11), and the study was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00003568). It was conducted in the time period from January 2011 to December 2014. Participation in the study was voluntary; patients’ written consent was documented. This manuscript was composed according to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement (e3); additionally, the description of the intervention followed the TIDieR-checklist (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) (e4). The study was funded under the funding priority scheme for healthcare-supply related research, “chronic disorders and patient orientation” by Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund [German Federal Pension Insurance] (funding reference 0421-FSCP-Z100).

Endpoints

The primary endpoints were defined as changes to participants’ health behaviors in the form of physical activity, dietary habits, and tobacco consumption, as well as their subjective state of health 6 and 12 months after the end of the rehabilitation measure (T3 and T4) compared with the start of the rehabilitation measure (T1). Only two measuring times were compared for medication adherence (T3 and T4). The secondary endpoints were defined as total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol concentrations, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood glucose, HbA1c measurements, and body mass index at T2 (end of the rehabilitation measure), T3, and T4 compared with T1.

Data collection instruments

We used the instrument by Singer and Wagner (16) to record physical activity, which is based on the data collection inventory by Baecke et al. (e5). With a total of 16 items it records the habitual physical activity of three dimensions: physical activity at work (8 items), exercise activity (4 items), and leisure-time physical activity (4 items). An overall index for employed persons was developed from these three individual indexes; the overall index for non-employed persons consists of the sum of the indexes leisure-time physical activity and exercise activity (minimum = 1, maximum = 5; the higher the score the better the exercise behavior).

To document dietary habits, we used the food frequency list of Winkler and Döring (17) to record how often different foods were consumed. On the basis of 24 items, the frequency of consumption is elicited; the response categories range from “almost daily” to “never” (in 6 stages). The following scheme was used for coding purposes: “optimal” consumption frequency (2 points), “normal” (1 point), and “deviant” consumption frequency (0 points). The food frequency list includes healthy foods (wholemeal bread, yoghurt, poultry, fish) as well as unhealthy ones (sweets, fizzy drinks, cold cuts). The point values of the 24 individual items are added to form a sum value (dietary pattern index), which can reach a maximum of 48 points. In order to record smoking behavior, participants’ current status (smoker, non-smoker) was documented.

In order to assess the current subjective state of health, we used the visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which is a component of the EuroQoL questionnaire, which includes six items on health-related quality of life (18). Participants enter their own assessment of their current state of health on a scale of 0 (poorest imaginable health condition) to 100 (best imaginable health condition).

The 4-item Morisky score (19) was used to document medication adherence. A low score (range 0–4 points) represents a high degree of adherence.

The four measuring time points fell into the time period December 2011 to September 2014.

Intervention

We developed an intervention consisting of the following elements:

Goal setting: Doctor and patient developed and documented in writing goals for behavioral and physiological protection factors and risk factors for phase III of the rehabilitation measure at the end of the rehabilitation program and documented these in writing.

Goal checking: Three months after the end of the rehabilitation measure, patients reflected in a discussion with their doctor or a therapist on sticking to their goals and were offered support if they had experienced problems in implementing the program.

Patient information brochure with disorder specific information, especially relating to behavioral protection factors and risk factors.

Patient passport to document the measured values for the physiological protection factors and risk factors over time.

Manual for doctors for standardized motivational interviewing for goal setting and goal checking.

Active participation of the patients in the rehabilitation measure during their goal setting and goal checking sessions aimed to enable these patients to act more independently as a result of increased decision and control competence.

The prerequisite for all this is comprehensive information, counseling, and support according to the principles of shared decision making or participatory decision making (e6). The discussions took their direction from health-related behavioral goals (regular physical activity, a health-promoting diet, abstinence from tobacco) and evidence based protection factors and risk factors (lipid metabolism, blood pressure, blood glucose, and body weight parameters). The theoretical structure for the discussions was Schwarzer’s social cognitive process model (health action process approach model) (e7), which is used to explain and predict health-related actions.

According to this model, two different phases are gone through when someone changes their behavior—the motivation phase is followed by the phase of volition. The jointly developed goals are recorded in a goal setting document.

Because of results from the qualitative study phase, which implied that male rehabilitation patients required support in terms of their dietary habits and female patients in terms of physical activity, male patients in the goal checking group additionally received a recipe book on Mediterranean diet and female patients an exercise diary in which to document physical activity.

Statistical analyses

The evaluation was conducted according to the intention to treat principle, in order to maintain the structural identity of the study groups achieved by randomization in these analyses as well (e8). Initially, sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors were studied, as were protection factors and risk factors in a comparison between the three study arms IGa, IGb, and CG at the start of the rehabilitation measure (Table 1). Additionally, patient characteristics were stratified by gender (Table 2). Interval scaled variables were tested by using monofactorial analysis of variance, variables with a nominal scale level were tested by using the chi-square test for frequency distributions.

In the longitudinal analysis, the change in primary endpoints between the start of the rehabilitation and the measurements taken at 6 and 12 months after the end of the rehabilitation in the context of the latent change model has been predicted (20). Owing to the different way in which the index is developed, additional stratified analyses were undertaken for employed and non-employed rehabilitation patients for physical activity. Because of the low prevalence of smokers, no analyses comparing the study groups were undertaken for tobacco consumption.

The latent change model is characterized by the fact that an unknown course of the studied result parameters can be analyzed between the different measuring times (e9). In a single step, using structural equation modeling, the change in latent difference variables between measuring times T1, T3, and T4 is modeled simultaneously for the three study groups—in this case, the change in physical activity, dietary behaviors, and the subjective state of health over time; medication adherence was included only at T3 and T4.

An analogous approach was used for the secondary endpoints; measurements were taken at all four time points, T1 to T4, and therefore included in the analyses. Co-variates in the model were age, sex, and participation in a heart group in contrast to non-participation in a heart group. The latent change model models changes (and not the absolute values) over time, the regression coefficients (b) in Table 3 and eTables 1– 3should be interpreted as the respective change compared with the baseline value at T1 (“constant”, first row of the tables).

Possible differences between the sexes as the primary and secondary endpoints evolve over time were tested statistically by comparison of the gender-stratified latent change models by using the chi-square test. In this way it was possible to study whether the effects in the three study groups over time were identical in men and women. The degrees of freedom of the chi-square tests used here are determined by multiplying the measuring times with the number of parameters included in the model.

The primary endpoints were evaluated in a confirmatory way. The primary endpoints were adjusted by using the Bonferroni correction as a consequence of multiple statistical tests, and the significance level was defined as α = 0.01. The analyses relating to subgroups and secondary endpoints were exploratory. The statistical evaluation of the data for the cross sectional analyses was done by using the software package SPSS 20.0, and the evaluation of the longitudinal analyses by using R.

Key Messages.

In the present study, goal setting for improved health behaviors did not have any effect on primary and secondary endpoints.

Subgroup analyses provided indications for a possible effect in the exercise behavior in everyday life among women in employment and non-employed men.

Participating in a heart group seems to have a beneficial effect on women in employment in terms of their exercise behavior in everyday life.

A mean of seven goals was set for the time after the rehabilitation measure. Female rehabilitation patients (n = 10) realized 74% of their goals, and male patients (n = 10) realized 57% of theirs (qualitative study result).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

We thank the doctors and patients who participated in the quantitative study phase: Dr. med. Christoph Altmann (MEDIAN Gesundheitspark Bad Gottleuba), Dr. med. Hildegard Bollwein (formerly Klinik Höhenried, Bernried), Volkmar Dietzel (MEDIAN Gesundheitspark Bad Gottleuba), Dr. med. Waltraud Fahrig (formerly Ambulantes Rehabilitationszentrum Hubertus, Berlin), Dr. med. Hermann Fischer (Zentrum für ambulante Rehabilitation Herz & Kreislauf, Dresden), Dr. med. Stefan Grosche (Klinikzentrum Mühlengrund, Bad Wildungen), Dr. med. Heike Hafemann-Gietzen (formerly Frankenklinik Campus Bad Neustadt), Annett Hlousek (MEDIAN Gesundheitspark Bad Gottleuba), Dr. med. Britta Humann (herzhaus Berlin), Dr. med. Ute Kober (Klinikzentrum Mühlengrund, Bad Wildungen), Diethelm Neetz (formerly RehaCentrum Hamburg), Dr. med. Sabine Nitsche (Rehazentrum Westend, Berlin), Dr. med. Sieglinde Spörl-Dönch (Frankenklinik Campus Bad Neustadt). During the qualitative study phase we received support from patients and staff at the following centers, for which we express our thanks: Reha-Zentrum Seehof, Teltow; Vivantes Rehabilitation GmbH, Berlin; Strandklinik Boltenhagen; herzhaus, Berlin; Ambulantes Rehabilitationszentrum Hubertus, Berlin; MEDIAN Gesundheitspark, Bad Gottleuba; Rehazentrum Rankestraße, Berlin; Zentrum für ambulante Rehabilitation Herz & Kreislauf, Dresden.

Funding

The study was funded by the German Federal Pension Insurance [Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund] (funding reference 0421-FSCP-Z100).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt. Gesundheit, Todesursachen in Deutschland. Statistisches Bundesamt. Fachserie 12, Reihe 4 www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Todesursachen2120400147004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. 2015. (last accessed on 13 November 2015)

- 2.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:892–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannuzzi P, Saner H, Björnstad H. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: position paper of the Working Group on Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1273–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoberg E, Bestehorn K, Wegscheider K, Brauer H. Auffrischungskurse nach kardiologischer Anschlussrehabilitation (HANSA-Studie) DRV-Schriften. 2004;52:150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahmann HW, Wüsten B, Nuß B, Muche R, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Intensivierte kardiologische Nachsorge nach stationärer Anschlußheilbehandlung. Ergebnisse der INKA-Studie. Herzmedizin. 2006;23:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittag O, China C, Hoberg E, et al. Outcomes of cardiac rehabilitation with versus without a follow-up intervention rendered by telephone (Luebeck follow-up trial): overall and gender-specific effects. Inter J Rehabil Res. 2006;29:295–302. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328010ba9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanssen TA, Nordrehaug JE, Eide GE, Hanestad BR. Improving outcomes after myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial evaluating effects of a telephone follow-up intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:429–437. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32801da123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keck M. Intensivierte Nachsorge zur Verbesserung der kardiovaskulären Risikofaktoren sowie anderer relevanter Reha-Outcomes bei Patienten mit manifester koronarer Herzerkrankung mittels Telefonnachsorge. DRV-Schriften. 2009;83:357–358. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redaèlli M, Simic D, Kohlmeyer M, Schwitalla B, Seiwerth B, Mayer-Berger W. Effektivität und Effizienz in der kardiovaskulären Rehabilitation - Ergebnisse nach 3 Jahren SeKoNa. DRV-Schriften. 2010;88:411–413. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes AR, Mutrie N, Macintyre PD. Effect of an exercise consultation on maintenance of physical activity after completion of phase III exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:114–121. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280116485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore SM, Charvat JM, Gordon NH, et al. Effects of a CHANGE intervention to increase exercise maintenance following cardiac events. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:53–62. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed RJ, Tillmann A, Kufleitner HE, Thürmer U, Dürsch M. Evaluating the efficacy of an education and treatment program for patients with coronary heart disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:802–808. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Grande G, Loewel H, Völler H, Mittag O. Gender-specific issues in cardiac rehabilitation: do women with ischaemic heart disease need specially tailored programmes? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:163–171. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280128bce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grande G. Genderspezifische Aspekte der Gesundheitsversorgung und Rehabilitation nach Herzinfarkt. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2008;51:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s00103-008-0417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morse J, Niehaus L. Mixed method design: Principles and procedures. Walnut Creck, California: Left Coast Press. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer R, Wagner P. Überprüfung eines (Kurz-)Fragebogens zur Erfassung der habituellen körperlichen Aktivität. In: Meck S, Klussmann PG, editors. Festschrift für Dieter Voigt. Münster: LIT; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkler G, Döring A. Validation of a short qualitative food frequency list used in several German large scale surveys. Z Ernährungswiss. 1998;37:234–241. doi: 10.1007/pl00007377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morisky D, Green L, Levine D. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steyer R, Eid M, Schwenkmezger P. Modeling true intraindividual change: True change as a latent variable. Methods of Psychological Research Online. 1997;2:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel A, Stamm-Balderjahn S. Welche Ziele setzen sich kardiologische RehabilitandInnen am Ende der Rehabilitation und lassen sich diese auch umsetzen? Erste Ergebnisse der CARO-PRE-II-Studie. DRV-Schriften. 2012;98:402–403. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudeck G, Höner O. Volitional Intervention within Cardiac Exercise Therapy (VIN-CET): Long-term effects on physical activity and health-related quality of life. Appl Psychol-Hlth We. 2011;3:151–171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen V, De Gucht V, Dusseldorp E, Maes S. Lifestyle modification programmes for patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;20:620–640. doi: 10.1177/2047487312462824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chase JA. Systematic review of physical activity intervention studies after cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26:351–358. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182049f00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:406–441. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrier S, Blanchard CM, Vallis M, Giacomantonio N. Behavioural interventions to increase the physical activity of cardiac patients: a review. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18:15–32. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833ace0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Mayring P. Weinheim: Beltz; 2010. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlage und Techniken. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Meuser M, Nagel U. Das Experteninterview - konzeptionelle Grundlagen und methodische Anlage. In: Pickel S, Pickel G, Lauth H-J, Jahn D, editors. Methoden der vergleichenden Politik- und Sozialwissenschaft. Neue Entwicklungen und Anwendungen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2009. pp. S. 465–S 479. [Google Scholar]

- e3.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nut. 1982;36:936–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Klemperer D, Rosenwirth M. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung; 2005. Shared Decision Making: Konzept, Voraussetzungen und politische Implikationen. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Schwarzer R. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2004. Psychologie des Gesundheitsverhaltens. [Google Scholar]

- e8.Kabisch M, Ruckes C, Seibert-Grafe M, Blettner M. Randomized controlled trials: part 17 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:663–668. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Geiser C, Eid M, Nussbeck FW, Courvoisier DS, Cole DA. Analyzing true change in longitudinal multitrait-multimethod studies: application of a multimethod change model to depression and anxiety in children. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:29–45. doi: 10.1037/a0017888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sabine Stamm-Balderjahn, Martin Brünger, Anne Michel, Christa Bongarth, Karla Spyra

The present study used a mixed methods design (15). During the qualitative phase of the study, guideline-based interviews and group discussions were conducted with patients and medical experts, in order to identify specific expectations and cognitions (for example, ideas for goals) among male and female rehabilitation patients for sustained health behavior. We conducted a randomized controlled intervention study with four measuring points in order to test the hypothesis of whether goal setting has a positive effect on health behaviors.

Qualitative study phase

We conducted 40 interviews and four group discussions with patients, as well as eight expert interviews with scientists/academics and treating medical professionals. The guideline-based interviews were conducted by topic and were recorded with a digital audio recorder. After transcription of the audio files, the patient interviews were evaluated on the basis of an analysis of their content, following the flow model by Mayring (e1). By developing a differentiated system of categories, the previously defined elements from the text material were extracted and allocated. The aim is to reflect conceptual associations that represent general factors on a so called case structure level that go beyond the level of individual cases. The evaluation strategies of Meuser and Nagel (e2) were used to evaluate the expert interviews. The analysis consisted of five working steps, to be done in sequence, that aimed to extricate the common elements beyond the individual case from the interviews and to reduce the volume of data.

Quantitative study phase

Design

We conducted a randomized controlled intervention study with several measuring time points (start [T1] and end [T2], as well as 6 [T3] and 12 [T4] months after the end of the rehabilitation measure).

Participants and sample

40 patients (47.5% women) and 8 experts participated in the qualitative phase. 545 patients (48.1% women) from five outpatient and five inpatient rehabilitation centers in five federal states (Berlin, Bavaria, Hamburg, Hesse, and Saxony) were included in the intervention study; the inclusion criteria were: patients who had had an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or aorto-coronary venous bypass surgery (ACVB) and who were aged between 18 and 85 years.

Study participants were allocated to one of three study groups: a goal checking group IGa (n = 132), in which a goal setting interview was conducted with patients at the end of the rehabilitation measure and a goal checking interview three months after the end of the rehabilitation; a goal setting group IGb (n = 143), where a goal setting interview was conducted at the end of the rehabilitation measure; and a control group CG (n = 270), in which patients received routine treatment. The initial randomization took place at the onset of the rehabilitation measure; patients were allocated either to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG). The second randomization took place at the end of the rehabilitation measure; the patients in IG were allocated either to the goal checking group IGa or the goal setting group IGb (Figure 1).

Ethics approval and data protection

Ethics approval was granted by the ethics committee at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA1/056/11), and the study was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00003568). It was conducted in the time period from January 2011 to December 2014. Participation in the study was voluntary; patients’ written consent was documented. This manuscript was composed according to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement (e3); additionally, the description of the intervention followed the TIDieR-checklist (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) (e4). The study was funded under the funding priority scheme for healthcare-supply related research, “chronic disorders and patient orientation” by Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund [German Federal Pension Insurance] (funding reference 0421-FSCP-Z100).

Endpoints

The primary endpoints were defined as changes to participants’ health behaviors in the form of physical activity, dietary habits, and tobacco consumption, as well as their subjective state of health 6 and 12 months after the end of the rehabilitation measure (T3 and T4) compared with the start of the rehabilitation measure (T1). Only two measuring times were compared for medication adherence (T3 and T4). The secondary endpoints were defined as total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol concentrations, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood glucose, HbA1c measurements, and body mass index at T2 (end of the rehabilitation measure), T3, and T4 compared with T1.

Data collection instruments

We used the instrument by Singer and Wagner (16) to record physical activity, which is based on the data collection inventory by Baecke et al. (e5). With a total of 16 items it records the habitual physical activity of three dimensions: physical activity at work (8 items), exercise activity (4 items), and leisure-time physical activity (4 items). An overall index for employed persons was developed from these three individual indexes; the overall index for non-employed persons consists of the sum of the indexes leisure-time physical activity and exercise activity (minimum = 1, maximum = 5; the higher the score the better the exercise behavior).

To document dietary habits, we used the food frequency list of Winkler and Döring (17) to record how often different foods were consumed. On the basis of 24 items, the frequency of consumption is elicited; the response categories range from “almost daily” to “never” (in 6 stages). The following scheme was used for coding purposes: “optimal” consumption frequency (2 points), “normal” (1 point), and “deviant” consumption frequency (0 points). The food frequency list includes healthy foods (wholemeal bread, yoghurt, poultry, fish) as well as unhealthy ones (sweets, fizzy drinks, cold cuts). The point values of the 24 individual items are added to form a sum value (dietary pattern index), which can reach a maximum of 48 points. In order to record smoking behavior, participants’ current status (smoker, non-smoker) was documented.

In order to assess the current subjective state of health, we used the visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which is a component of the EuroQoL questionnaire, which includes six items on health-related quality of life (18). Participants enter their own assessment of their current state of health on a scale of 0 (poorest imaginable health condition) to 100 (best imaginable health condition).

The 4-item Morisky score (19) was used to document medication adherence. A low score (range 0–4 points) represents a high degree of adherence.

The four measuring time points fell into the time period December 2011 to September 2014.

Intervention

We developed an intervention consisting of the following elements:

Goal setting: Doctor and patient developed and documented in writing goals for behavioral and physiological protection factors and risk factors for phase III of the rehabilitation measure at the end of the rehabilitation program and documented these in writing.

Goal checking: Three months after the end of the rehabilitation measure, patients reflected in a discussion with their doctor or a therapist on sticking to their goals and were offered support if they had experienced problems in implementing the program.

Patient information brochure with disorder specific information, especially relating to behavioral protection factors and risk factors.

Patient passport to document the measured values for the physiological protection factors and risk factors over time.

Manual for doctors for standardized motivational interviewing for goal setting and goal checking.

Active participation of the patients in the rehabilitation measure during their goal setting and goal checking sessions aimed to enable these patients to act more independently as a result of increased decision and control competence.

The prerequisite for all this is comprehensive information, counseling, and support according to the principles of shared decision making or participatory decision making (e6). The discussions took their direction from health-related behavioral goals (regular physical activity, a health-promoting diet, abstinence from tobacco) and evidence based protection factors and risk factors (lipid metabolism, blood pressure, blood glucose, and body weight parameters). The theoretical structure for the discussions was Schwarzer’s social cognitive process model (health action process approach model) (e7), which is used to explain and predict health-related actions.

According to this model, two different phases are gone through when someone changes their behavior—the motivation phase is followed by the phase of volition. The jointly developed goals are recorded in a goal setting document.

Because of results from the qualitative study phase, which implied that male rehabilitation patients required support in terms of their dietary habits and female patients in terms of physical activity, male patients in the goal checking group additionally received a recipe book on Mediterranean diet and female patients an exercise diary in which to document physical activity.

Statistical analyses

The evaluation was conducted according to the intention to treat principle, in order to maintain the structural identity of the study groups achieved by randomization in these analyses as well (e8). Initially, sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors were studied, as were protection factors and risk factors in a comparison between the three study arms IGa, IGb, and CG at the start of the rehabilitation measure (Table 1). Additionally, patient characteristics were stratified by gender (Table 2). Interval scaled variables were tested by using monofactorial analysis of variance, variables with a nominal scale level were tested by using the chi-square test for frequency distributions.

In the longitudinal analysis, the change in primary endpoints between the start of the rehabilitation and the measurements taken at 6 and 12 months after the end of the rehabilitation in the context of the latent change model has been predicted (20). Owing to the different way in which the index is developed, additional stratified analyses were undertaken for employed and non-employed rehabilitation patients for physical activity. Because of the low prevalence of smokers, no analyses comparing the study groups were undertaken for tobacco consumption.

The latent change model is characterized by the fact that an unknown course of the studied result parameters can be analyzed between the different measuring times (e9). In a single step, using structural equation modeling, the change in latent difference variables between measuring times T1, T3, and T4 is modeled simultaneously for the three study groups—in this case, the change in physical activity, dietary behaviors, and the subjective state of health over time; medication adherence was included only at T3 and T4.

An analogous approach was used for the secondary endpoints; measurements were taken at all four time points, T1 to T4, and therefore included in the analyses. Co-variates in the model were age, sex, and participation in a heart group in contrast to non-participation in a heart group. The latent change model models changes (and not the absolute values) over time, the regression coefficients (b) in Table 3 and eTables 1– 3should be interpreted as the respective change compared with the baseline value at T1 (“constant”, first row of the tables).

Possible differences between the sexes as the primary and secondary endpoints evolve over time were tested statistically by comparison of the gender-stratified latent change models by using the chi-square test. In this way it was possible to study whether the effects in the three study groups over time were identical in men and women. The degrees of freedom of the chi-square tests used here are determined by multiplying the measuring times with the number of parameters included in the model.

The primary endpoints were evaluated in a confirmatory way. The primary endpoints were adjusted by using the Bonferroni correction as a consequence of multiple statistical tests, and the significance level was defined as α = 0.01. The analyses relating to subgroups and secondary endpoints were exploratory. The statistical evaluation of the data for the cross sectional analyses was done by using the software package SPSS 20.0, and the evaluation of the longitudinal analyses by using R.