The DNA-binding domain of SETMAR was successfully crystallized in a complex with its ancestral terminal inverted repeat and a variant of this sequence through a systematic approach, and initial Se SAD phasing was achieved through the judicious addition of Met residues.

Keywords: crystallization, DNA-binding domain, transposable element, terminal inverted repeat, Hsmar1, SETMAR

Abstract

Transposable elements have played a critical role in the creation of new genes in all higher eukaryotes, including humans. Although the chimeric fusion protein SETMAR is no longer active as a transposase, it contains both the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and catalytic domain of the Hsmar1 transposase. The amino-acid sequence of the DBD has been virtually unchanged in 50 million years and, as a consequence, SETMAR retains its sequence-specific binding to the ancestral Hsmar1 terminal inverted repeat (TIR) sequence. Thus, the DNA-binding activity of SETMAR is likely to have an important biological function. To determine the structural basis for the recognition of TIR DNA by SETMAR, the design of TIR-containing oligonucleotides and SETMAR DBD variants, crystallization of DBD–DNA complexes, phasing strategies and initial phasing experiments are reported here. An unexpected finding was that oligonucleotides containing two BrdUs in place of thymidines produced better quality crystals in complex with SETMAR than their natural counterparts.

1. Introduction

Through a fortuitous sequence of molecular events, SETMAR arose as a chimeric fusion protein in anthropoid primates (Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸), giving rise to a protein that retains the lysine methyltransferase activity associated with its SET domain (Fnu et al., 2011 ▸; Carlson et al., 2015 ▸) but has lost the ability to function as a transposase, despite containing an intact copy of the Hsmar1 DNA tranposon-derived transposase (Roman et al., 2007 ▸; Beck et al., 2011 ▸; Liu et al., 2007 ▸; Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸; Miskey et al., 2007 ▸; Kim et al., 2014 ▸; Robertson & Zumpano, 1997 ▸). SETMAR is widely expressed in a number of human tissues and has been reported to play a role in DNA double-strand break repair, the restarting of stalled replication forks and chromosome decatenation (De Haro et al., 2010 ▸; Lee et al., 2005 ▸; Shaheen et al., 2010 ▸; Williamson et al., 2008 ▸).

The Hsmar1 transposase comprises a DNA-binding domain (DBD) with two predicted helix–turn–helix (HTH) motifs in addition to a catalytic domain. The amino-acid sequence of the DBD is unusually conserved, with only two amino-acid substitutions in the 50 million years since the ancestral Hsmar1 transposon entered the primate lineage downstream of a SET domain (Robertson & Zumpano, 1997 ▸; Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸), and the DBD retains the ability to bind specifically to a 19-base-pair element within its ancestral terminal inverted repeat (TIR) sequence. In contrast, the catalytic domain is less well conserved and harbors 17 amino-acid substitutions compared with the predicted ancestral sequence (Robertson & Zumpano, 1997 ▸; Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸). Importantly, this domain now has a DDN motif in place of the mariner-associated DDD motif, which is thought to play an important role in metal binding (Lohe et al., 1997 ▸). Thus, the SETMAR transposase has lost its ancestral site-specific TIR DNA-cleavage activity and can no longer function as a transposase (Miskey et al., 2007 ▸; Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸; Liu et al., 2007 ▸). Restoration of its ancestral transposase activity required the substitution of 21 amino-acid residues, restoring it to a consensus sequence with four additional substitutions introduced based on a phylogenetic approach (Miskey et al., 2007 ▸).

Crystal structures have been determined for the SET and transposase catalytic domains, providing a basis for probing the functions of these two domains (PDB entries 3bo5 and 3k9j, 3k9k and 3f2k, respectively; Structural Genomics Consortium, unpublished work; Goodwin et al., 2010 ▸). Structures of the catalytic domain have been determined in complexes with both Ca2+ and Mg2+, each bound to a single site, suggesting that loss of the third aspartic acid residue may in fact prevent the binding of a second metal ion involved in catalysis (Goodwin et al., 2010 ▸). To determine the nature of the interaction of SETMAR with DNA, we sought to crystallize a complex of the DBD bound to both its ancestral TIR DNA and a sequence variant. Binding to non-TIR DNA sequences suggests that SETMAR may have evolved to bind more general sequences within the genome and has implications for its biological function. Here, we describe the crystallization and initial phasing experiments for SETMAR–DNA complexes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Oligonucleotides and macromolecule production

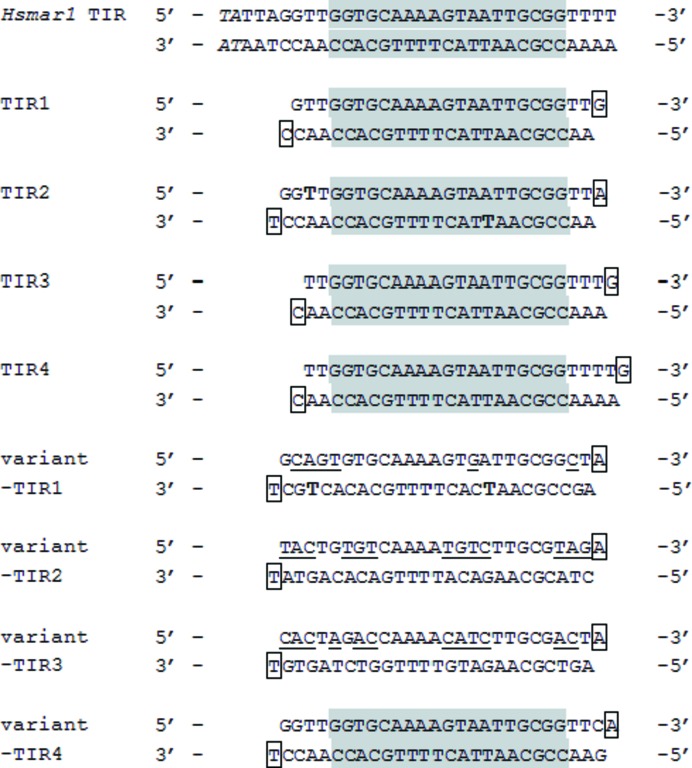

The oligonucleotides used in this study were purchased from Midland Certified Reagent (Midland, Texas, USA). They were synthesized on a 1 µmol scale, desalted and then used without further purification. A total of eight duplex oligonucleotides were screened in crystallization experiments (Fig. 1 ▸). Stock solutions of 5 mM duplex DNA were dissolved and annealed in distilled, deionized water.

Figure 1.

Oligonucleotides used for crystallization trials. Hsmar1 TIR-based DNA sequences were used for crystallization. The consensus Hsmar1 TIR sequence is shown for the left TIR element of the predicted ancestral transposon (top). The italic TA is the characteristic flanking dinucleotide in the Tc1/mariner transposon superfamily. Oligonucleotides screened include the 19 bp mariner binding site (shaded in gray) for TIR and the variant TIR sequences. Boxes indicate overhanging nucleotides expected to facilitate packing of the DNA in the lattice. Underlined bases indicate variations from the TIR sequence, and thymidines shown in bold in TIR2 and variant-TIR1 were replaced with bromodeoxyuridines for Br SAD phasing experiments.

For crystallographic studies, two different SETMAR DBD constructs were used, one including residues 329–440 and the other residues 316–440. To construct the first construct, DNA encoding residues 329–671 was PCR-amplified from an existing pET-15b vector of the SETMAR transposase domain (Goodwin et al., 2010 ▸) and subcloned into the pET-28-derived pSUMO vector (Mossessova & Lima, 2000 ▸) between BamHI and XhoI sites (primers 329-671_F and 329-671_R). For the second construct, DNA encoding residues 316–671 was PCR-amplified from pFLAG-CMV4 full-length SETMAR (wild type; Beck et al., 2008 ▸) and subcloned into the pSUMO vector between BamHI and XhoI sites (primers 316-671_F and 316-671_R). Since the DNA encoding the DBD is about 300 bp, in order to ease the purification of the PCR product by gel extraction, the forward primer was designed to include the N-terminal 6×His-SUMO tag-coding region in the pET-28-derived pSUMO vector. Using primers DBD_F and DBD_R, DNA encoding 6×His-SUMO-SETMAR (amino acids 329–440) or 6×His-SUMO-SETMAR (amino acids 316–440) was PCR-amplified from the cognate plasmid encoding residues 329–671 or 316–671, respectively, and subcloned into pSUMO vector between NcoI and XhoI sites. The primers used for subcloning are listed in Table 1 ▸. In this study, all primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, Iowa, USA). The final plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing (Genewiz Inc., South Plainfield, New Jersey, USA). To optimize the crystallization conditions, C381R and C381S mutations were generated individually using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). Primers for site-directed mutagenesis are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

F indicates forward and R reverse for the primers.

| Source organism | Human | Human |

| Construct | Final 329–440 (first 329–671, then 6×His-SUMO-329–440) | Final 316–440 (first 316–671, then 6×His-SUMO-316–440) |

| DNA source | pET-15b transposase domain of SETMAR (wild type) | pFLAG-CMV4 full-length SETMAR (wild type) |

| 329-671_F (left) and 316-671_F (right) primers | ATATCGGATCCATGAAAATGATGTTAGACAAAAAGCAAATTCG | TATATCGGATCCGTGTTCCCCTCCTGCAAGCGATTGA |

| 329-671_R (left) and 316-671_R (right) primers | TATAGCTCGAGTTAATCAAAATAGGAACCATTACAATC | TATAGCTCGAGTTAATCAAAATAGGAACCATTACAATC |

| DBD_F primer | GATATACCATGGGCAGCAGCCATCATCATCATCATC | GATATACCATGGGCAGCAGCCATCATCATCATCATC |

| DBD_R primer | TATAGCTCGAGTTACACCTTTCCAATTTGCTTCAAATGTC | TATAGCTCGAGTTACACCTTTCCAATTTGCTTCAAATGTC |

| Cloning vector | p6×His-SUMO | p6×His-SUMO |

| Expression vector | p6×His-SUMO | p6×His-SUMO |

| Expression host | E. coli Rosetta (DE3) | E. coli Rosetta (DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence | SMKMMLDKKQIRAIFLFEFKMGRKAAETTRNINNAFGPGTANERTVQWWFKKFRKGDESLEDEERSGRPSEVDNDQLRAIIEADPLTTTREVAEELNVNHSTVVRHLKQIGKV | SVFPSCKRLTLETMKMMLDKKQIRAIFLFEFKMGRKAAETTRNINNAFGPGTANERTVQWWFKKFSKGDESLEDEERSGRPSEVDNDQLRAIIEADPLTTTREVAEELNVNHSTVVRHLKQIGKV |

The DBDs of SETMAR used in this study, including residues 329–440 or 316–440 and various substituted versions of these constructs, were expressed and purified as described previously (Kim et al., 2014 ▸). For selenomethionine (SeMet) protein constructs, double mutations (I359M and L423M) were introduced into the 329–440(C381R) plasmid to generate the pET-28b-SUMO-SETMAR-329-440(C381R)(I359M)(L423M) construct using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). The primers used to introduce additional methionines are shown in Supplementary Table S1. SeMet protein was expressed using an protocol adapted from the literature (Van Duyne et al. 1993 ▸). Escherichia coli Rosetta cells (EMD Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) were grown in M9 minimal medium. At an OD of 0.5–0.6, an amino-acid cocktail solution (Lys, Phe and Thr at 100 mg per litre of culture; Ile, Leu and Val at 50 mg per litre of culture) was added to inhibit methionine synthesis. Selenomethionine was supplied to the medium to a final concentration of 60 mg l−1. Cells were induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG and were grown at 18°C overnight. The SeMet protein-purification protocol is the same as that for the wild-type protein. In brief, following lysis and centrifugation, the cell lysate was applied onto an Ni–NTA column and then subjected to on-column cleavage with the SUMO-specific Ulp1 protease to remove the N-terminal His-SUMO affinity tag. The eluent was then applied onto a tandem Q Sepharose/SP Sepharose column; the protein was eluted from the SP Sepharose column, subjected to size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and then concentrated to approximately 5 mM for storage in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT at −80°C.

2.2. Crystallization

All of the DBD variants were mixed with duplex DNA (5 mM stock) to give a final protein:DNA molar ratio of 1:1.2 in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and incubated on ice for 15 min prior to crystallization. The resulting protein concentration was 500 µM. Initial crystallization screens were performed using a Gryphon crystallization robot (Art Robbins Instruments, Sunnyvale, California, USA) with 0.6 µl drops (0.3 µl complex solution plus 0.3 µl reservoir solution) and 60 µl reservoirs in 96-well sitting-drop vapor-diffusion plates (Intelli-Plate 96-3 LVR, Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, California, USA). Subsequently, all crystals were grown by vapor diffusion in 2 µl (1 µl complex solution plus 1 µl reservoir solution) hanging drops at 20°C suspended over 500 µl reservoir solution. The crystals for data collection were obtained by microseeding, cryoprotected in a solution containing 20% ethylene glycol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen before data collection. Crystallization information is summarized in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Crystallization.

ND, not determined.

| Protein–DNA complex | DBD (329–440)–TIR2 | DBD (329–440) (C381S)–TIR2 | DBD (329–440) (C381S)–variant TIR1 | DBD (316–440) (C381S)–variant TIR1 | DBD (329–440) (C381R)–TIR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Vapor diffusion | Vapor diffusion | Vapor diffusion | Vapor diffusion | Vapor diffusion |

| Image | Figs. 2 ▸(a) and 2 ▸(b) | Fig. 2 ▸(c) | Fig. 2 ▸(d) | Fig. 2 ▸(e) | Fig. 2 ▸(f) |

| Plate type | VDX | VDX | VDX | VDX | VDX |

| Temperature (K) | 293 | 293 | 293 | 293 | 293 |

| Protein concentration | 0.5 mM:0.6 mM | 0.5 mM:0.6 mM | 0.5 mM:0.6 mM | 0.5 mM:0.6 mM | 0.5 mM:0.6 mM |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT | 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT | 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT | 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT | 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 0.2 M Li2SO4, 0.1 M bis-tris pH 5.5, 25%(w/v) PEG 3350 | 25% poly(acrylic acid sodium) 5100, 0.10 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.02 M MgCl2 | 0.01 M Mg(CH3COO)2, 0.05 M MES pH 5.6, 2.5 M (NH4)2SO4 | 0.10 M Mg(HCO2)2, 15% PEG 3350 | 0.025 M MgSO4 hydrate, 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 1.8 M (NH4)2SO4 |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 2 µl, 1:1 | 2 µl, 1:1 | 2 µl, 1:1 | 2 µl, 1:1 | 2 µl, 1:1 |

| Volume of reservoir (ml) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Space group | ND | C2 | ND | C2221 | C2221 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

Data were collected using a MAR Mosaic CCD on the GM/CA 23-ID-B beamline and were processed using an automated script with XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▸), POINTLESS (Evans, 2006 ▸) and AIMLESS (Evans & Murshudov, 2013 ▸). Statistics for data processing and scaling are shown in Table 3 ▸.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Crystal | DBD 329–440 (C381R)–TIR2 | DBD 329–440 (C381R)–TIR2 | Blended data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffraction source | GM/CA 23-ID-B | GM/CA 23-ID-B | GM/CA 23-ID-B |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97945 | 0.97945 | 0.97945 |

| Temperature (K) | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| Detector | MAR Mosaic CCD | MAR Mosaic CCD | MAR Mosaic CCD |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 350 | 350 | 350 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.5 | 0.5 | NA |

| Total rotation range (°) | 140 | 140 | NA |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 2 | 2 | NA |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 72.41, 167.01, 66.61 | 71.63, 166.29, 65.40 | 72.02, 166.65, 66.01 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.31 | 0.80 | NA |

| Resolution range (Å) | 47.04–3.75 (4.19–3.75) | 83.14–3.24 (3.5–3.24) | 46.71–4.17 (4.67–4.17) |

| Total No. of reflections | 48084 | 70866 | 67781 |

| No. of unique reflections | 4262 | 6468 | 3177 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.0 (98.7) | 99.6 (97.0) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 11.3 (11.5) | 11.0 (11.2) | 21.3 (22.3) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 13.0 (3.0) | 10.8 (2.8) | 20.5 (10.7) |

| R meas | 0.162 (1.066) | 0.215 (1.199) | 0.158 (0.476) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 98.12 | 76.55 | 109.20 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Variation of the protein and DNA components of the complex

The ability to crystallize protein–DNA complexes involving a small DBD relative to the size of the DNA depends critically on optimizing both the protein and DNA components of the complex. In this study, we began with the wild-type SETMAR DBD including residues 329–440 based on a sequence comparison with the related transposase Mos1. Using SEC, the SETMAR DBD was found to elute as a single peak (Supplementary Fig. S1). Addition of TIR DNA to SETMAR DBD results in the formation of a complex which elutes at a higher molecular weight following SEC (Supplementary Fig. S1), consistent with tight binding. An apparent K d of 3 nM for the binding of SETMAR DBD to TIR DNA was determined by fluorescence polarization (Kim et al., 2014 ▸).

Four different complexes including DBD 329–440 and one of the four TIR oligonucleotides (Fig. 1 ▸) were screened in crystallization trials. The four TIR-containing oligonucleotides were designed based on prior knowledge of the Hsmar1 binding site within the TIR (Cordaux et al., 2006 ▸) and the available crystal structures of Tc3 and Mos1 complexed with DNA (Watkins et al., 2004 ▸; Richardson et al., 2009 ▸). In these initial designs, the placement of the 19 bp mariner binding site (MBS) relative to the ends of the oligonucleotides and the length of the duplex regions was varied. The DNA sequences include two 24-mer duplexes with one 5′ overhanging nucleotide on each strand, TIR1 and TIR3, and two 25-mer duplexes with one 5′ overhanging nucleotide, TIR2 and TIR4. In TIR1, the 19 bp MBS was placed centrally with three additional 5′ nucleotides from the TIR sequence and two nucleotides 3′ to the recognition element. TIR3 included two 5′ nucleotides and three 3′ nucleotides on either side of the MBS. TIR2 included four 5′ nucleotides and two 3′ nucleotides, and TIR4 two 5′ nucleotides and four 3′ nucleotides. Either G:C or A:T overhangs were screened for these two positions of the MBS.

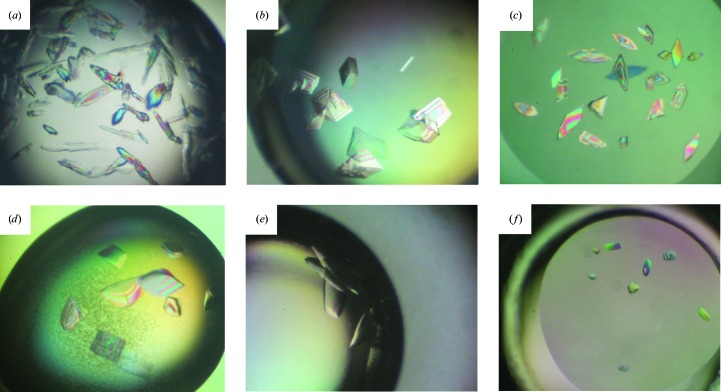

To identify crystallization conditions, approximately 400 conditions contained within the Index, Natrix, Natrix 2, Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, PEG/Ion and PEG/Ion 2 kits (Hampton Research) were screened. Crystals were obtained for the complex of DBD 329–440 with TIR2 from Index condition G2: 0.2 M Li2SO4, 0.1 M bis-tris pH 5.5, 25% PEG 3350. These crystals grew primarily in layers with few single crystals but diffracted to approximately 8 Å resolution (Fig. 2 ▸ a, Supplementary Fig. S2a). Using freshly purified protein we were able to reproduce these crystals, but not with protein that had been stored even for a few days. However, we found that the addition of TCEP resulted in much larger single crystals that could be reproduced with stored protein (Fig. 2 ▸ b); these crystals also diffracted X-rays to about 8 Å resolution (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Figure 2.

Crystal images of initial crystallization trials. (a) DBD 329–440 (wild type) with TIR2. (b) DBD 329–440 (wild type) with TIR2 with TCEP additive. (c) DBD 329–440 (C381S) with TIR2. (d) DBD 329–440 (C381S) with variant TIR1. (e) DBD 316–440 (C381S) with variant TIR1. (f) DBD 329–440 (C381R) with TIR2.

Since TCEP is highly effective at keeping sulfhydryls reduced, thus limiting disulfide-bond formation, we then looked for cysteine residues in the protein sequence that might form intermolecular disulfide bonds during the crystallization process and identified one Cys residue, Cys381, within this DBD. The equivalent position in Mos1 is Lys54, which is solvent-exposed in the crystal structure of the paired-end Mos1 complex (Richardson et al., 2009 ▸). Interestingly, it was this same cysteine that was substituted with Arg, together with other critical substitutions, to reconstruct an active Hsmar1 transposase from the human genome (Miskey et al., 2007 ▸). Thus, we introduced two different substitutions for Cys381: C381S, representing a relatively conservative substitution, and C381R, as found in the revertant Hsmar1. We then screened DBD 329–440 (C381S) complexed with each of the four TIR oligonucleotides. Crystals of DBD 329–440 (C381S) complexed with TIR2 were obtained from Index condition E11 consisting of 25% poly(acrylic acid sodium) 5100, 0.10 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.02 M MgCl2 (Fig. 2 ▸ c), and were similar in morphology to those of the wild-type DBD–TIR2 complex grown in the presence of TCEP. A very small cryocooled crystal diffracted X-rays to 4 Å resolution and belonged to the monoclinic space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 78.7, b = 168.6, c = 74.9 Å, β = 108.35°. In this case, attempts to cryocool larger crystals were unsuccessful, with diffraction limited to low resolution. In screening DBD 329–440 (C381R) complexed with each of the first four oligonucleotides (Fig. 1 ▸), crystals were obtained for a complex with TIR2 from Natrix condition D9, which consists of 0.025 M magnesium sulfate hydrate, 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 1.8 M ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2 ▸ f). The crystals obtained with the natural DNA sequence diffracted to 4 Å resolution (Supplementary Fig. S2d) and belonged to space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 74.73, b = 168.76, c = 72.19 Å.

Another variable screened with the goal of improving the crystals was the sequence of the DNA used for crystallization. Nucleotides within the TIR2 DNA sequence that were not critical for SETMAR binding in the reported EMSA analysis were substituted to create variant TIR sequences (Fig. 1 ▸). Our screen of these variant TIR oligonucleotides complexed with DBD 329–440 (C381S) produced crystals with variant TIR1 in Natrix condition A2, which consists of 0.01 M magnesium acetate, 0.05 M MES pH 5.6, 2.5 M ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2 ▸ d). However, cryocooling this crystal form proved to be problematic, as indicated by the low-resolution X-ray diffraction images. Interestingly, no promising crystals were obtained from DBD 329–440 (C381R) with the variant TIR1 complex.

In the process of molecular domestication of the Hsmar1 transposase gene downstream of the SET gene, a previously noncoding sequence between these two current exons was converted to encode a linker region. This linker region of the DBD N-terminal extension might fold back to interact with the minor groove and provide another DNA-interacting element, as seen in the Tc3–DNA complex (Watkins et al., 2004 ▸). To explore this possibility in SETMAR, we made a DBD protein including residues 316–440, 14 amino acids longer than the 329–440 construct, and screened this DBD with each of the eight oligonucleotides (Fig. 1 ▸). Crystals were obtained for a complex including DBD 316–440 (C381S) with variant TIR1 in 0.10 M magnesium formate, 15% PEG 3350 (Fig. 2 ▸ e). An initial diffraction image for this crystal is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2(c). Later, improved crystals of DBD 316–440 (C381S) with variant TIR1 diffracted to 3.15 Å resolution and belonged to space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 72.23, b = 164.39, c = 67.96 Å.

A total of four TIR-derived sequences and four variant TIR sequences were used for crystallization trials in complexes with the following DBD constructs: 329–440, 329–440 (C381S), 329–440 (C381R) and 316–440 (C381S) (Fig. 1 ▸). The DBD–DNA complexes that ultimately resulted in usable diffraction quality crystals were DBD 329–440 (C381R)–TIR2 and DBD 316–440 (C381S)–variant TIR1.

3.2. Considerations in phasing strategies

Although the DBDs of SETMAR and Mos1 are 30% identical, the DNA-recognition sequences for each protein are unrelated. This is relevant because the DNA makes up approximately 55% of the mass of the complex. Thus, we pursued two single anomalous dispersion (SAD) phasing strategies: Se SAD and Br SAD. Since three of the four intrinsic Met residues are clustered at the N-terminus and are likely to be disordered, we sought to improve the Se signal by increasing the number of ordered SeMet residues within the protein for experimental Se SAD phasing purposes. Through a sequence comparison with the related transposase Mos1, we identified conserved Leu or Ile residues within α-helical regions of HTH1 and HTH2 motifs in Mos1 that might be well ordered and tolerate substitution by Met to improve the Se anomalous signal (Supplementary Fig. S3). Four doubly mutated constructs were made including the following pairs: L343M and L404M, L343M and L423M, I359M and L404M, and I359M and L423M. The double-mutant protein constructs were introduced into the 329–440 (C381R) plasmid. Of these, DBD 329–440 (C381R)(I359M)(L423M) was stably expressed in sufficient quantities for crystallization experiments. With the introduction of two additional methionines, there are a total of six possible Se sites in the SeMet-labeled protein (Supplementary Fig. S3).

SETMAR DBD 329–440 (C381R) and SeMet-substituted DBD were subjected to analysis on an Agilent 6520 Q-TOF (quadrupole time-of-flight) mass spectrometer, which has a mass accuracy of 1 Da, to ensure that the SeMet-substituted protein had been produced (Supplementary Fig. S4). The calculated mass for the native DBD 329–440 (C381R) is 13 078.8 Da and that observed was 13 079.06 Da. For the SeMet protein, the largest peak observed had a mass of 13 397.17 Da, consistent with the expected mass of 13 396.52 Da for the incorporation of six SeMet residues in place of the four native methionines and two additional Met substitutions.

For Br SAD experimental phasing, two thymidines (dT) were replaced with Br-dU in two strands for TIR2 and within a single strand for variant TIR1, with the criteria that those sites were not symmetrically positioned within the oligonucleotide and would not be expected to be in direct contact with the protein based on prediction (Fig. 1 ▸). To confirm the presence of Br in the crystals, we measured several X-ray absorption scans. An example is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5 for the variant TIR1 crystals, with a peak at 13 487.52 eV, consistent with spectra for brominated DNA (Supplementary Fig. S5). Data were collected for both variant TIR and TIR complexes to 3.1 and 2.8 Å resolution, respectively. As analyzed in HKL-3000, there was no observable anomalous signal for the DBD 329–440 (C381R)–TIR complex and a very weak signal for the DBD 316–440 (C381S)–variant TIR1 complex at ∼4.5 Å. Attempts to obtain a good solution for the Br sites at many different resolutions were unsuccessful, and electron-density maps phased from the sites of these solutions were uninterpretable. Although Br SAD phasing experiments were not successful, crystals grown for DBD complexes with brominated oligonucleotides were uniformly of better quality than those grown for the corresponding complex with the natural DNA sequences. As a consequence, all of the crystals used for phasing experiments contained brominated oligonucleotides. We can only speculate that differences in the solubility or purity of these oligonucleotides contributed to the improved crystal quality.

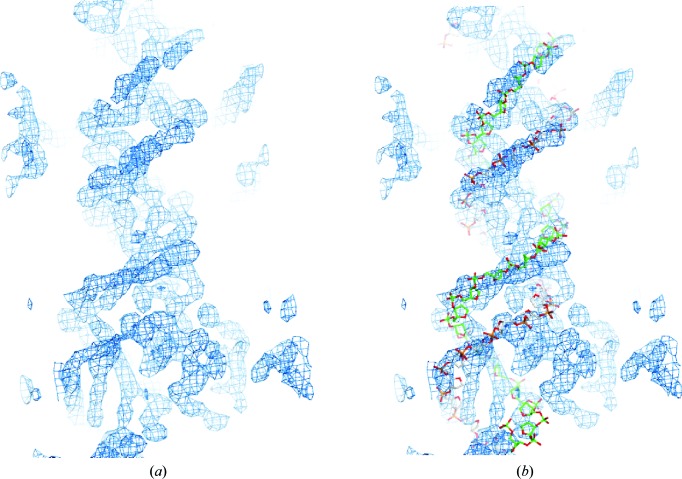

3.3. Low-resolution Se SAD phasing

Two data sets were collected on beamline 23-ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source for SeMet-derivatized DBD 329–440 (C381R)(I359M)(L423M) complexed with brominated TIR2 DNA: one to 3.75 Å resolution and one to 3.24 Å resolution (Table 3 ▸). Attempts to identify Se sites from either data set alone were not successful. Therefore, using BLEND (Foadi et al., 2013 ▸), the two SeMet SAD data sets were merged, producing a 4.2 Å resolution data set. Three of the possible six sites were identified using AutoSol as implemented in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸), namely I359M, L423M and the intrinsic Met348. These sites were used to phase an electron-density map at 4.2 Å resolution (Fig. 3 ▸). The electron density of the DNA phosphate backbone was identified in this map, and an initial model for the DNA phosphate backbone and a polyalanine model for the two HTH motifs were built. Having completed these initial experiments, we optimized the crystallization of SeMet-substituted DBD 329–440 (C381R)(I359M)(L423M) complexed with Br-dU TIR2 oligonucleotides and ultimately obtained crystals that diffracted to higher resolution and completed a structure determination, which will be reported elsewhere.

Figure 3.

Preliminary low-resolution electron-density map of a SETMAR DBD–DNA complex. (a) Experimental electron-density map phased at 4.2 Å resolution. Phases were calculated from three Se positions from data combined in BLEND from two SeMet-derivative crystals. (b) An initial phosphate backbone model is shown with the experimental density map.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X16012723/nj5260sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Nukri Sanishvili and Craig Ogata for assistance at the GM/CA 23-ID-B beamline. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R01 CA151367 (SHL and MMG). GM/CA@APS has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). This research used the resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Beck, B. D., Lee, S.-S., Williamson, E., Hromas, R. A. & Lee, S.-H. (2011). Biochemistry, 50, 4360–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beck, B. D., Park, S.-J., Lee, Y.-J., Roman, Y., Hromas, R. A. & Lee, S.-H. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9023–9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S. M., Moore, K. E., Sankaran, S. M., Elias, J. E. & Gozani, O. (2015). J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12040–12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cordaux, R., Udit, S., Batzer, M. A. & Feschotte, C. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 8101–8106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Haro, L. P., Wray, J., Williamson, E. A., Durant, S. T., Corwin, L., Gentry, A. C., Osheroff, N., Lee, S.-H., Hromas, R. & Nickoloff, J. A. (2010). Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 5681–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fnu, S., Williamson, E. A., De Haro, L. P., Brenneman, M., Wray, J., Shaheen, M., Radhakrishnan, K., Lee, S.-H., Nickoloff, J. A. & Hromas, R. (2011). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 540–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Foadi, J., Aller, P., Alguel, Y., Cameron, A., Axford, D., Owen, R. L., Armour, W., Waterman, D. G., Iwata, S. & Evans, G. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 1617–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, K. D., He, H., Imasaki, T., Lee, S.-H. & Georgiadis, M. M. (2010). Biochemistry, 49, 5705–5713. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S., Chen, Q., Kim, S.-K., Nickoloff, J. A., Hromas, R., Georgiadis, M. M. & Lee, S.-H. (2014). J. Biol. Chem. 289, 10930–10938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H., Oshige, M., Durant, S. T., Rasila, K. K., Williamson, E. A., Ramsey, H., Kwan, L., Nickoloff, J. A. & Hromas, R. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 18075–18080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, D., Bischerour, J., Siddique, A., Buisine, N., Bigot, Y. & Chalmers, R. (2007). Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1125–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lohe, A. R., De Aguiar, D. & Hartl, D. L. (1997). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 1293–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miskey, C., Papp, B., Mátés, L., Sinzelle, L., Keller, H., Izsvák, Z. & Ivics, Z. (2007). Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 4589–4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mossessova, E. & Lima, C. D. (2000). Mol. Cell, 5, 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J. M., Colloms, S. D., Finnegan, D. J. & Walkinshaw, M. D. (2009). Cell, 138, 1096–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robertson, H. M. & Zumpano, K. L. (1997). Gene, 205, 203–217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roman, Y., Oshige, M., Lee, Y.-J., Goodwin, K., Georgiadis, M. M., Hromas, R. A. & Lee, S.-H. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 11369–11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, M., Williamson, E., Nickoloff, J., Lee, S.-H. & Hromas, R. (2010). Genetica, 138, 559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Duyne, G. D., Standaert, R. F., Karplus, P. A., Schreiber, S. L. & Clardy, J. (1993). J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Watkins, S., van Pouderoyen, G. & Sixma, T. K. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 4306–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Williamson, E. A., Rasila, K. K., Corwin, L. K., Wray, J., Beck, B. D., Severns, V., Mobarak, C., Lee, S.-H., Nickoloff, J. A. & Hromas, R. (2008). Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5822–5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X16012723/nj5260sup1.pdf