Abstract

Concise biomimetic syntheses of the Strychnos-Strychnos-type bis-indole alkaloids (−)-leucoridine A (1) and C (2) were accomplished through the biomimetic dimerization of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3). En route to 3, the known alkaloids (+)-geissoschizoline (8) and (−)-dehydrogeissoschizoline (10) were also prepared. DFT calculations were employed to elucidate the mechanism, which favors a stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization sequence over the alternate hetero-Diels–Alder cycloaddition reaction.

Keywords: biomimetic synthesis, indole alkaloids, natural products, reaction mechanisms, total synthesis

Complex natural products continue to spark the creativity of synthetic organic chemists, and the indole alkaloids are an excellent example.[1] In 2010, Kam and co-workers isolated (−)-leucoridines A (1) and C (2), complex Strychnos-Strychnos alkaloids from the stem-bark extracts of Leuconotis griffithii (Figure 1).[2] Cursory inspection of 2 suggests it can be readily prepared through the hydrolysis of the indolenine nucleus in 1, which itself appears to be a dimer of the monoterpene indole alkaloid (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3).[3]

Figure 1.

Structures of leucoridine A (1), B (2), and the proposed biogenetic precursor dihydrovalparicine (3).

Bis-indoles 1 and 2 showed moderate cytotoxicity against KB cells (IC50 values of 0.57 and 10.91 μgmL−1, respectively) and vincristine-resistant KB/VJ300 cells (IC50 values of 2.39 and 11.80 μgmL−1, respectively). While the biological activities of these congeners justifies their study, we were particularly drawn to the complex molecular architectures of 1 and 2 and hypothesized that these natural products are most likely formed through a highly stereoselective dimerization of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3).[2] Spirocyclization to form the epimeric C16 congener would be precluded on steric grounds by the rigid and bulky (S)-2-ethyl-4-azatricyclo[5.3.3.04,8] undecane nucleus.[4] Over the years, we have developed synthetic methods for the concise syntheses of various Strychnos alkaloids.[5] Accordingly, we sought to test our biogenetic hypothesis that 1 and 2 could be synthesized through the dimerization of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3).

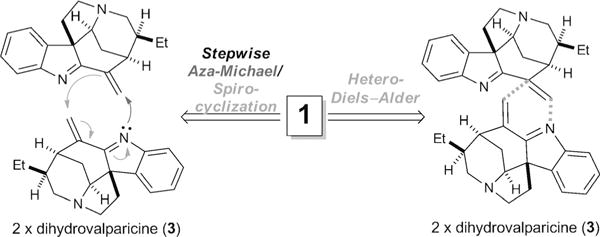

Further consideration of our biogenetic hypothesis led us to propose two mechanistic pathways by which 3 could dimerize (Scheme 1). On the one hand, 1 could be assembled through a stepwise aza-Michael addition of the indolenine nitrogen of one monomer to the electrophilic C16–C22 alkene of another, followed by diastereoselective spirocyclization onto an activated C16′–C22′ alkene.[6] On the other hand, a concerted and highly diastereoselective hetero-Diels–Alder reaction could be envisioned.[7]

Scheme 1.

The two possible mechanisms for the biomimetic dimerization of (−)-leucoridine A (1) from (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3): stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization and hetero-Diels–Alder.

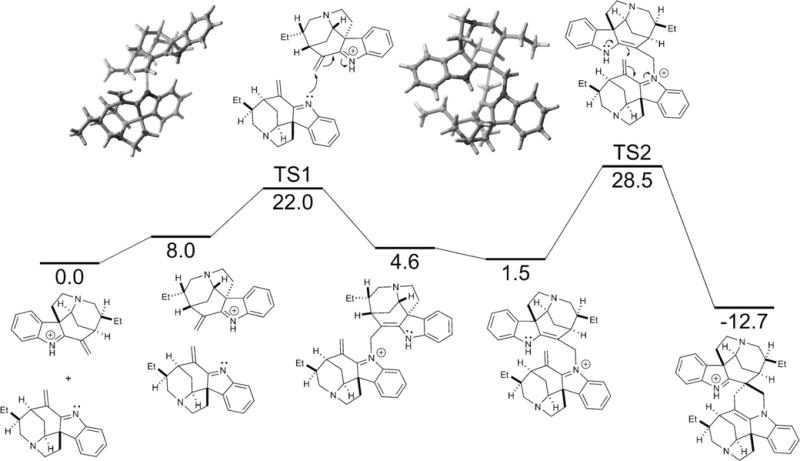

To distinguish between these two mechanistic possibilities, we first turned to computational quantum chemistry. A search for transition states (TSs) corresponding to the two pathways was performed at the SMD-M06-2X/6-31 + G(d) level of theory.[8] Computations were based primarily on the reaction of 3 with another monomer of 3 protonated at the indolenine nitrogen atom, which corresponds to the most likely acid-catalyzed pathway (see below). An extensive search failed to locate a transition state corresponding to a concerted hetero-Diels–Alder cycloaddition, thus suggesting that such a pathway is not viable. Instead, we identified a stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization pathway with the free energy profile (298 K) given in Figure 2. The reaction proceeds through initial formation of a pre-reaction complex followed by the aza-Michael addition via TS1, with a free energy barrier of 22.0 kcalmol−1. The resulting adduct undergoes rotation about the formed C–N bond, followed by cyclization via TS2, which lies 28.5 kcalmol−1 higher in free energy than the separated reactants. This yields the conjugate acid of leucoridine A (1), which is 12.7 kcalmol−1 lower in free energy than the separated reactants.

Figure 2.

Free-energy profile of the acid-catalyzed stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization pathway (298 K).

We also considered the non-acid-catalyzed dimerization of 3 at the same level of theory. Initially, we considered the dimerization of 2-vinyl-3H-indole as a model for the nonacid-catalyzed dimerization of 3. In this case, we located TS structures for both stepwise and concerted pathways. The barrier for the concerted pathway is predicted to be 1.6 kcal mol−1 higher in free energy than that for the stepwise pathway. However, for the non-acid-catalyzed dimerization of 3, a systematic scan over the formation and breaking of C–C and C–N bonds revealed that only a stepwise pathway exists on this potential energy surface (see the Supporting Information).

In this non-acid-catalyzed stepwise pathway, the cycloaddition step is rate limiting, lying 5.8 kcal mol−1 higher in free energy than the initial aza-Michael addition. Thus, regardless of whether this process proceeds via protonation of the indolenine nitrogen, computations support a stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization mechanism.

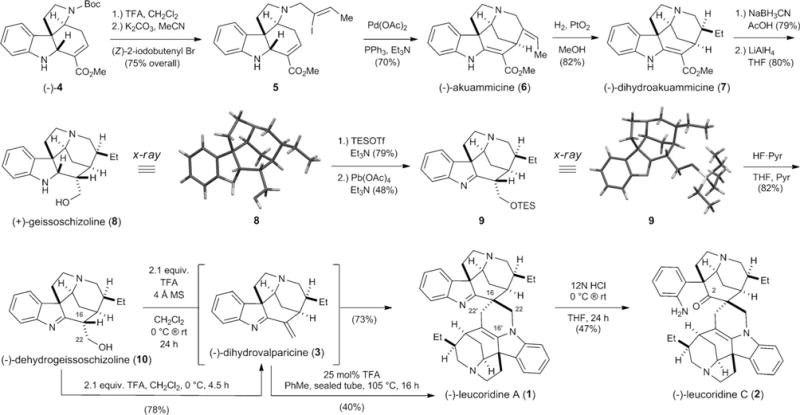

To test our biogenetic hypothesis, we focused on an expedient synthesis of dihydrovalparicine (3). Accordingly, we began with tetracycle (−)-4, which was prepared in four operations from commercial N-tosyl indole 3-carboxaldehyde (Scheme 2).[5e] Removal of the N-Boc group in 4 with TFA followed by site-selective N-alkylation with (Z)-2-iodo-2-butenyl bromide[9] afforded 5 in 75% yield over two steps.[5d] To install the fifth ring in 3, we employed a tactic developed by Rawal,[10] namely the intramolecular Heck reaction, which furnished (−)-akuammicine (6)[5d] in 70% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3) and its biomimetic dimerization to form (−)-leucoridines A (1) and C (2).

At this stage, stereoselective hydrogenation of the ethylidene moiety in 6 under the agency of Adams’s catalyst delivered (−)-dihydroakuammicine (7)[11] in 82% yield. With 7 in hand, we made use of Kuehne’s conditions (i.e., NaBH3CN in AcOH) to reduce the vinylogous carbamate, which afforded a separable mixture of C16 diastereomers (α/β = 7:1) in 79% yield.[12] Reduction of the carbomethoxy group in the requisite major diastereomer with LiAlH4 gave the known indole alkaloid (+)-geissoschizoline (8) in 80% yield.[13] Moreover, we were able to obtain a single-crystal X-ray structure of 8 to confirm the stereochemical course of both reduction reactions.

The conversion of (+)-geissoschizoline (8) into (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3) required 1) chemoselective indoline-to-indolenine oxidation in the presence of the primary C22 hydroxyl group and 2) dehydration of the latter to install the C16–C22 olefin. Execution of the first task proved problematic and TES protection of the C22 carbinol with TESOTf and Et3N had to be employed (79% yield). Screening various oxidation conditions revealed Pb(OAc)4 buffered with Et3N to be the best approach, furnishing indolenine 9 in 48% yield.[14] Gratifyingly, we were able to perform single-crystal X-ray analysis on 9 to unambiguously confirm its structure. The second task began with removal of the TES group with HF·Pyr in 82% yield, which gave the known alkaloid (−)-dehydrogeissoschizoline (10).[13] Dehydration of the C16 carbinol was best realized with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), a tactic initially reported by Vanderwal and co-workers.[15] In the event, we obtained a 78% yield of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3) following careful purification over neutral alumina.

With (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3) in hand, we proceeded to test our biogenetic hypothesis. Attempts to effect the dimerization reaction under neutral conditions by heating solutions of 3 in various solvents (e.g., THF, 1,4-dioxane, toluene, DMF, diglyme) at temperatures up to 145°C (sealed tube) for 16–48 h resulted in either decomposition or recovered starting material. We reasoned that the dimerization reaction would proceed more readily under acidic conditions (i.e., electrophilic activation) through protonation of the indolenine nitrogen. To this end, we screened a variety of conditions and ultimately found that heating a solution of 3 in toluene at 105°C for 16 h in the presence of 25 mol% TFA afforded (−)-leucoridine A (1) in 40% yield of isolated product (Scheme 2). While we were delighted to have prepared the targeted natural product, a more efficient process for the dimerization of 3 was sorely needed. The sensitive nature of 3 suggested that bypassing its isolation would surely increase the yield of 1; moreover, sequestration of water would drive the equilibrium toward dimerization. After extensive experimental optimization, we discovered that when (−)-dehydrogeissoschizoline (10) was treated with 2.1 equivalents of TFA and 4 Å molecular sieves in CH2Cl2 for 24 h, we obtained (−)-leucoridine A (1) in a satisfactory 73% yield (Scheme 2).[16]

Finally, we found that the addition of 12N HCl to a solution of 1 in THF for 24 h resulted in ring-opening of the indolenine to deliver (−)-leucoridine C (2) in 47% yield. Spectroscopic data for synthetic (−)-1 and (−)-2 (e.g., 1H and 13C NMR, IR, HRMS, optical rotation) were in complete agreement with those reported by Kam and co-workers.[2,17] In summary, we have accomplished the first asymmetric total syntheses of the Strychnos-Strychnos alkaloids (−)-leucoridines A (1) and C (2) by employing a biomimetic dimerization reaction of (−)-dihydrovalparicine (3). We optimized the syntheses of 1 and 2 by preparing 3 in situ by dehydrating (−)-dehydrogeissoschizoline (10) with TFA in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieves. Finally, we employed DFT calculations to elucidate the mechanism of dimerization, and the results suggest that a stepwise aza-Michael/spirocyclization sequence is operative as opposed to the alternative hetero-Diels–Alder pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from NSF (CHE-1111558) and the Welch Foundation (A-1775) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Charles DeBrosse (Director of NMR Facilities at Temple Chemistry) for assistance with NMR experiments and Dr. Richard Pederson (Materia, Inc.) for catalyst support, as well as the Texas A&M Supercomputing Facility for computational resources.

Footnotes

In memory of Grant R. Krow

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201505198.

Contributor Information

Praveen Kokkonda, Department of Chemistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (USA).

Keaon R. Brown, Department of Chemistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (USA)

Trevor J. Seguin, Department of Chemistry, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX 77843 (USA)

Dr. Steven E. Wheeler, Department of Chemistry, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX 77843 (USA)

Dr. Shivaiah Vaddypally, Department of Chemistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (USA)

Dr. Michael J. Zdilla, Department of Chemistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (USA)

Dr. Rodrigo B. Andrade, Department of Chemistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (USA).

References

- 1.a) Somei M, Yamada F. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:73–103. doi: 10.1039/b316241a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ishikura M, Abe T, Choshi T, Hibino S. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:694–752. doi: 10.1039/c3np20118j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ishikura M, Yamada K, Abe T. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1630–1680. doi: 10.1039/c005345g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ishikura M, Yamada K. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:803–852. doi: 10.1039/b820693g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan CY, Etoh T, Hayashi M, Komiyama K, Kam TS. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1107–1111. doi: 10.1021/np1001187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim KH, Low YY, Kam TS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:5037–5039. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonjoch J, Casamitjana N, Quirante J, Rodriguez M, Bosch J. J Org Chem. 1987;52:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Sirasani G, Andrade RB. Org Lett. 2009;11:2085–2088. doi: 10.1021/ol9004799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sirasani G, Paul T, Dougherty W, Jr, Kassel S, Andrade RB. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3529–3532. doi: 10.1021/jo100516g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sirasani G, Andrade RB. Org Lett. 2011;13:4736–4737. doi: 10.1021/ol202056w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sirasani G, Andrade RB. In: Strategies and Tactics in Organic Synthesis. Harmata M, editor. Vol. 9. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2013. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]; e) Zhao SZ, Sirasani G, Vaddypally S, Zdilla MJ, Andrade RB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:8309–8311. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2013;125:8467–8469. [Google Scholar]; f) Munagala S, Sirasani G, Kokkonda P, Phadke M, Krynetskaia N, Lu PH, Sharom FJ, Chaudhury S, Abdulhameed MDM, Tawa G, Wallqvist A, Martinez R, Childers W, Abou-Gharbia M, Krynetskiy E, Andrade RB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:1148–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Teijaro CN, Munagala S, Zhao SZ, Sirasani G, Kokkonda P, Malofeeva EV, Hopper-Borge E, Andrade RB. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10383–10390. doi: 10.1021/jm501189p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzuya K, Mori N, Watanabe H. Org Lett. 2010;12:4709–4711. doi: 10.1021/ol101846z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tietze LF, Kettschau G. Stereoselective Heterocyclic Synthesis I. 1997;189:1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theo Chem Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin WY, Kabir MS, Wang ZJ, Rallapalli SK, Ma J, Cook JM. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3339–3349. doi: 10.1021/jo100279w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawal VH, Michoud C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1695–1698. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amat M, Coll MD, Bosch J, Espinosa E, Molins E. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:935–948. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehne ME, Xu F. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9427–9433. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele JCP, Veitch NC, Kite GC, Simmonds MSJ, Warhurst DC. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:85–88. doi: 10.1021/np0101705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenkert E, Pestchanker MJ. J Org Chem. 1988;53:4875–4877. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin DBC, Nguyen LQ, Vanderwal CD. J Org Chem. 2012;77:17–46. doi: 10.1021/jo2020246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shortly after publication of this article as an Angewandte Chemie Early View, it was brought to our attention that leucoridine A had been prepared earlier this year via semisynthesis from natural geissoschizoline by Evanno and co-workers by using TFA:; Benayad S, Beniddir MA, Evanno L, Poupon E. Eur J Org Chem. 2015:1894–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proton chemical shift differences for H3 in synthetic and isolated 2 (i.e., 3.75 and 3.79 ppm, respectively) are likely the result of concentration differences or protonation states. We thank the reviewers for pointing this out.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.