Abstract

Objective

To examine the health and functional characteristics of Mexican and Mexican American adults aged ≥80.

Method

Data came from Wave I (2001) and Wave III (2012) of the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), and Wave IV (2000–2001) and Wave VII (2010–2011) of the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (HEPESE).

Results

In 2000–2001, diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, and stroke were higher in the HEPESE than in the MHAS. In the HEPESE, activities of daily living (ADL) difficulties and all health conditions, except heart attack, were greater in 2010–2011 than in 2000–2001. In the MHAS, hypertension and ADL difficulties were greater, and arthritis was lower in 2012 compared with 2001. In 2010–2011, all self-reported health conditions were higher in the HEPESE compared with the 2012 observation of the MHAS.

Discussion

The observed differences may reflect worse health for Mexican Americans, health care access, reporting bias, and more selective survival to very old age in Mexico.

Keywords: Hispanic health, aging, Mexico, Mexican Americans

Introduction

The population of Mexico is aging rapidly. The percentage of the population 65 years of age and older in Mexico has increased from 5% in the year 2000 to 6.4% in 2010 and is projected to reach 18.9% in 2050 (United Nations, 2015). This increase in the older adult population has been largely attributed to the significant reduction in mortality since the 20th century (Palloni, Pinto-Aguirre, & Pelaez, 2002). While the number of adults who reach old age has increased, there are substantial inequalities throughout Mexico in living conditions, employment opportunities, and income (Hoffman & Angel Centeno, 2003; Moreno-Brid & Krozer, 2014). These inequalities have contributed to a unique epidemiological transition in Mexico, in which the country is experiencing not only a high disease burden from diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic non-communicable diseases but also a high burden of non-communicable diseases, especially in the underdeveloped southern region of Mexico (Stevens et al., 2008). This has important implications for public health in Mexico because older adults may have been exposed to both infectious and chronic disease factors, which can negatively affect health during old age (Wong & Palloni, 2009).

The demographic and epidemiologic transitions in Mexico have coincided with an increase in the Hispanic population in the United States (Colby & Ortman, 2015). The majority of Hispanics living in the United States are of Mexican origin (Gonzalez-Barrera & Lopez, 2013). Immigrants from Mexico to the United States do not represent a random subset of the general population in Mexico. Rather, immigrants are positively selected for health and behavioral characteristics, and Mexican immigrants tend to be in better overall health compared with Mexicans who do not immigrate to the United States (Breslau et al., 2011; Riosmena, Wong, & Palloni, 2013). The overall better health and health behaviors, in particular smoking, of immigrants are contributing factors to the greater life expectancy among Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic Whites in the United States (Lariscy, Hummer, & Hayward, 2015), especially among foreign-born Mexican Americans (Markides & Eschbach, 2005; Palloni & Arias, 2004).

However, Hispanics are more likely to engage in negative health behaviors consistent with U.S. culture (e.g., poor diet, smoking) the longer they live in the United States (Abraido-Lanza, Chao, & Florez, 2005; Ayala, Baquero, & Klinger, 2008). The adoption of poor health behaviors by Hispanic immigrants contributes to an overall decline in health (Antecol & Bedard, 2006) and to the high prevalence of diabetes (Selvin, Parrinello, Sacks, & Coresh, 2014), hypertension (Flegal, Carroll, Kit, & Ogden, 2012), and other chronic health conditions in this population. Previous research indicates that there are important differences in the health of older Mexican and Mexican American adults. Using data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (HEPESE) and Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), Patel, Peek, Wong, and Markides (2006) observed that Mexicans aged ≥65 had slightly higher percentage of disability as determined by difficulty in one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) compared with Mexican Americans aged 65 and above (16.3% vs. 13.1%). However, Mexican Americans were more likely to report having been diagnosed with arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart attack, and stroke compared with older Mexican adults (Patel et al., 2006).

The increased life expectancy in Mexico (World Health Organization, 2014) and among Mexican Americans (Arias, 2010) highlights the importance of studying the health characteristics of adults from these populations who survive to very old age. The present study uses data from participants of the HEPESE and MHAS aged ≥80 to examine the self-reported health and ADL characteristics of very old Mexican and Mexican Americans. Given the increase in the prevalence of chronic health conditions in Mexico and the United States, we hypothesize that the percentage of self-reported health conditions and ADL difficulty would have increased from Wave IV (2000–2001) to Wave VII (2010–2011) of the HEPESE, and from Wave I (2001) to Wave III (2012) of the MHAS.

Method

HEPESE and MHAS Cohorts

The HEPESE and MHAS are two ongoing longitudinal studies of Mexican American and Mexican adults, respectively. Detailed descriptions of the sampling techniques and methods of data collection for the HEPESE (Markides, Rudkin, Angel, & Espino, 1997) and MHAS (Wong, Michaels-Obregon, & Palloni, 2015) have been provided. Briefly, the HEPESE is a representative study of Mexican Americans age ≥65 residing in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California. More than half of the Mexican American population in the United States live in these five states (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). A total of 3,050 participants were interviewed during the baseline wave in 1993–1994, and eight waves have been completed as of 2013. During Wave V (2004–2005), a new cohort of 902 Mexican Americans age ≥75 was added to the original cohort. The MHAS is a nationally representative study of Mexican adults age ≥50 in 2001 (Wave I). A total of 15,186 participants were interviewed during Wave I, and follow-up observations were completed in 2003 (Wave II) and 2012 (Wave III).

For the present analysis, we selected all participants with available measures for self-reported health conditions and ADLs from Wave I (2001) of the MHAS and Wave IV (2000–2001) of the HEPESE who were age ≥80 (hereafter referred to as 2000–2001 observation period), as well as all participants age ≥80 from Wave III (2012) of the MHAS and Wave VII (2010–2011) of the HEPESE (hereafter referred to as 2010–2012 observation period). A total of 62 participants from the HEPESE and 73 participants from the MHAS who were missing data for health conditions and ADLs were excluded from the final sample. The 2000–2001 observation period included 761 participants of the MHAS and 666 participants of the HEPESE (n = 1,427), and the 2010–2012 observation period included 1,426 participants of the MHAS and 979 participants of the HEPESE (n = 2,405). The greater number of participants in the 2010–2012 observation period compared with the 2000–2001 observation period is due to the replenishing of the HEPESE cohort during Wave V (2004–2005) and because participants who were below 80 years of age in 2000–2001 became eligible to be included in the analysis during the 2010–2012 observation period.

Assessment of Health and Disability

The MHAS and HEPESE include self-reported measures for having ever been told by a physician or other health/medical professionals that he or she has arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, heart attack, and stroke. The MHAS and HEPESE both asked participants about their ability to walk across a small room, bathe, get dressed, eat, move from a bed to a chair, and use a toilet. Specifically, the MHAS participants were asked, “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty with …?” with potential responses being yes, no, can’t do, doesn’t do, don’t know, and refused. HEPESE participants were asked, “At the present time, do you need help from a person or special equipment or device for …?” with potential responses being need help, don’t need help, unable to do, don’t know, and refused. For our analysis, MHAS participants who responded yes or can’t do were categorized as being unable to independently perform the ADL activity, and HEPESE participants who responded need help or unable to do were categorized as being unable to independently perform the ADL.

Statistical Analysis

The sociodemographic and health characteristics during the study observation periods (2000–2001 and 2010–2012) stratified by study groups (MHAS and HEPESE) were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons between the MHAS and HEPESE for age, gender, education, marital status, and self-reported health conditions were made using independent t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression models fitted by generalized estimating equations were used to estimate the adjusted percentage of participants with each health condition in the 2000–2001 and 2010–2012 observation periods for the MHAS and HEPESE. Because some participants could be observed in 2000–2001 and 2010–2012, these models accounted for the potential dependence of observations by using a sandwich estimator to correct the standard error of the estimated regression coefficients. All models included age, gender, education, marital status, study group (MHAS and HEPESE), study observation period (2000–2001–2010–2012), and an interaction term between study group and study observation period. The interaction term was included to examine statistically significant changes in the adjusted percentage of self-reported health conditions and ADL difficulties from 2000–2001 to 2010–2012 within the MHAS and HEPESE, while controlling for participant characteristics (age, gender, education, and marital status). All tests of statistical significance were two sided with significance being p < .05. Analyses were performed with R version 3.1 (R Core Team, 2014) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

A summary of the sociodemographic, self-reported health, and ADL characteristics of participants in the MHAS and HEPESE for the 2000–2001 and 2010–2012 observation periods is presented in Table 1. The HEPESE included a significantly higher percentage of women in both the 2000–2001 and 2010–2012 observation periods, and participants of the HEPESE reported having completed significantly more years of education compared with participants of the MHAS. The age distributions were similar between the MHAS and HEPESE for the 2000–2001 observation period, but during the 2010–2012 observation period, participants of the HEPESE were 1 year older on average than participants of the MHAS (p < .01). Also, participants of the HEPESE were significantly more likely to be widowed compared with participants of the MHAS but only during the 2010–2012 observation period.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Mexicans and Mexican Americans Aged 80 and Above During 2000–2001 and 2010–2012.

| Characteristic | 2000–2001 cohort | 2010–2012 cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| MHAS (n = 761) | HEPESE (n = 666) | MHAS (n = 1,426) | HEPESE (n = 979) | |

| Age, M (SD) | 84.7 (4.5) | 84.9 (4.4) | 84.8 (4.4) | 85.8 (4.0) |

| L | ||||

| Male | 329 (43.2) | 237 (35.6) | 619 (43.4) | 343 (35.0) |

| Female | 432 (56.8) | 429 (64.4) | 807 (56.6) | 636 (65.0) |

| Education, n (%)* | ||||

| 0 years | 354 (46.5) | 134 (20.1) | 549 (38.5) | 159 (16.2) |

| 1–6 years | 337 (44.3) | 374 (56.2) | 726 (50.9) | 533 (54.4) |

| 7+ years | 70 (9.2) | 158 (23.7) | 151 (10.6) | 287 (29.3) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 273 (35.9) | 220 (33.0) | 501 (35.1) | 324 (33.1) |

| Not married | 81 (10.6) | 71 (10.7) | 150 (10.5) | 65 (6.6) |

| Widowed | 407 (53.5) | 375 (56.3) | 775 (54.3) | 590 (60.3) |

| Arthritis, n (%)* | ||||

| No | 541 (71.1) | 292 (43.8) | 1,130 (79.2) | 336 (34.3) |

| Yes | 220 (28.9) | 374 (56.2) | 296 (20.8) | 643 (65.7) |

| Diabetes, n (%)* | ||||

| No | 650 (85.4) | 485 (72.8) | 1,192 (83.6) | 626 (63.9) |

| Yes | 111 (14.6) | 181 (27.2) | 234 (16.4) | 353 (36.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%)* | ||||

| No | 433 (56.9) | 331 (49.7) | 728 (51.1) | 252 (25.7) |

| Yes | 328 (43.1) | 335 (50.3) | 698 (48.9) | 727 (74.3) |

| Heart attack, n (%) | ||||

| No | 713 (93.7) | 611 (91.7) | 1,351 (94.7) | 882 (90.1) |

| Yes | 48 (6.3) | 55 (8.3) | 75 (5.3) | 97 (9.9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | ||||

| No | 725 (95.3) | 621 (93.2) | 1,354 (95.0) | 875 (89.4) |

| Yes | 36 (4.7) | 45 (6.8) | 72 (5.0) | 104 (10.6) |

| ADL disability, n (%) | ||||

| No | 476 (62.5) | 427 (64.1) | 799 (56.0) | 493 (50.4) |

| Yes | 285 (37.5) | 239 (35.9) | 627 (44.0) | 486 (49.6) |

Note. Not married includes participants who were divorced, separated, or single/never married. Percentages based on column total. ADL = activities of daily living; MHAS = Mexican Health and Aging Study; HEPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.

p < .05.

Table 2 presents the adjusted odds ratios for self-reported health conditions for participants of the HEPESE compared with the MHAS during 2000–2001 and 2010–2012. In 2000–2001, HEPESE participants had significantly higher odds of reporting a diagnosis of diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, and stroke but not heart attack. During the 2010–2012 observation period, participants of the HEPESE had significantly higher odds for all self-reported health conditions compared with participants of the MHAS. Female respondents had significantly higher odds than males to have self-reported diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension, whereas males had significantly higher odds to report having experienced a heart attack. Advancing age was associated with greater odds for stroke, but the odds for self-reported diabetes and hypertension decreased with age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios From a Logistic, Multivariable Analysis Estimating Percentages of Specific Health Condition and ADL Disability.

| Variables | Diabetes | Arthritis | Heart attack | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.94* | [0.93, 0.96] | 0.99 | [0.98, 1.01] | 0.98 | [0.95, 1.01] |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 0.79* | [0.66, 0.95] | 0.67* | [0.57, 0.79] | 1.38* | [1.06, 1.79] |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Widow | 1.01 | [0.77, 1.31] | 0.96 | [0.75, 1.23] | 1.54 | [0.93, 2.54] |

| Married | 0.91 | [0.69, 1.21] | 0.80 | [0.62, 1.05] | 1.29 | [0.76, 2.17] |

| Education (years) | ||||||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1–6 | 1.16 | [0.95, 1.40] | 0.94 | [0.79, 1.11] | 1.03 | [0.76, 1.39] |

| ≥7 | 1.09 | [0.85, 1.40] | 0.83 | [0.66, 1.05] | 1.31 | [0.90, 1.92] |

| Study Cohort I | ||||||

| MHAS | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| HEPESE | 2.20* | [1.70, 2.86] | 3.16* | [2.52, 3.96] | 1.31 | [0.87, 1.97] |

| Study Cohort II | ||||||

| MHAS | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| HEPESE | 3.55* | [2.76, 4.57] | 4.85* | [3.91, 6.02] | 1.58* | [1.09, 2.30] |

| HEPESE | ||||||

| Study Cohort I | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Study Cohort II | 1.61* | [1.32, 1.97] | 1.54* | [1.26, 1.87] | 1.21 | [0.85, 1.71] |

| MHAS | ||||||

| Study Cohort I | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Study Cohort II | 1.19 | [0.95, 1.50] | 0.64* | [0.53, 0.78] | 0.82 | [0.56, 1.19] |

| Variables | Hypertension | Stroke | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.97* | [0.95, 0.98] | 1.03* | [1.00, 1.06] |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 0.64* | [0.55, 0.74] | 1.11 | [0.83, 1.48] |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Widow | 1.29* | [1.02, 1.62] | 1.10 | [0.68, 1.77] |

| Married | 1.16 | [0.91, 1.49] | 1.04 | [0.63, 1.73] |

| Education (years) | ||||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1–6 | 1.14 | [0.98, 1.33] | 0.78 | [0.58, 1.05] |

| ≥7 | 1.03 | [0.83, 1.27] | 0.65* | [0.43, 0.97] |

| Study Cohort I | ||||

| MHAS | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| HEPESE | 1.27* | [1.03, 1.58] | 1.59* | [1.02, 2.50] |

| Study Cohort II | ||||

| MHAS | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| HEPESE | 3.67* | [2.97, 4.53] | 2.64* | [1.77, 3.94] |

| HEPESE | ||||

| Study Cohort I | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Study Cohort II | 2.88* | [2.36, 3.52] | 1.65* | [1.15, 2.38] |

| MHAS | ||||

| Study Cohort I | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Study Cohort II | 1.26* | [1.06, 1.50] | 1.09 | [0.73, 1.64] |

Note. These models include participant characteristics, study cohort, study group, and the interaction between study cohort and study group. The adjusted odds ratios for study group are reported separately for Study Cohorts I and II. The adjusted odds ratios for study cohort are reported separately for HEPESE and MHAS. ADL = activities of daily living; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; MHAS = Mexican Health and Aging Study; HEPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.

p < .05.

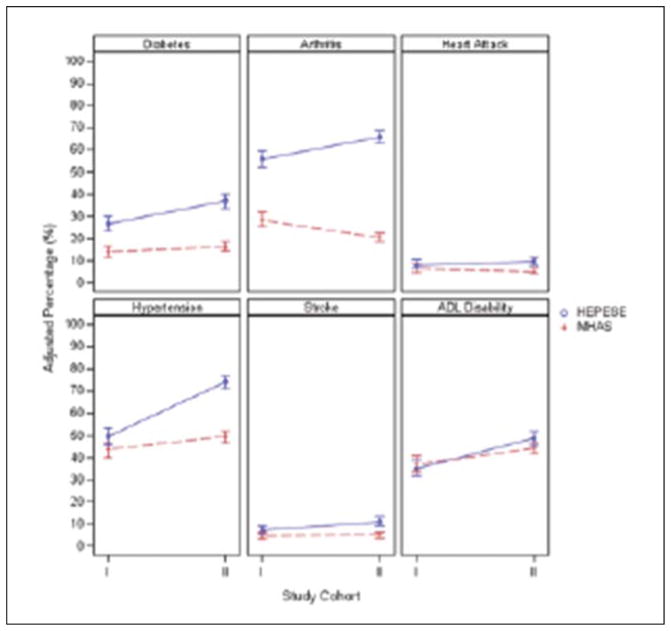

The changes in the adjusted percentage for self-reported health conditions and ADL difficulty from 2000–2001 to 2010–2012 in the MHAS and HEPESE are presented in Figure 1. Overall, the HEPESE exhibited greater increases in the percentage for self-reported health conditions and ADL difficulties from the 2000–2001 to 2010–2012 observation periods compared with the MHAS. In the HEPESE, the adjusted percentage for diabetes increased from 26.6% to 36.9% (p < .01). Furthermore, the adjusted percentage in the HEPESE for arthritis increased from 55.8% to 66.0% (p < .01), hypertension increased from 49.7% to 74.0% (p < .01), stroke increased from 6.9% to 10.9% (p = .01), and ADL difficulties increased from 35.1% to 48.9% (p < .01). The adjusted percentage for heart attack did not change significantly in the HEPESE (8.1% 2000–2001 to 9.6% 2010–2012).

Figure 1.

Adjusted percentage for self-reported health conditions and disability in the HEPESE and MHAS during 2000–2001 (Study Cohort I) and 2010–2012 (Study Cohort II).

Note. Adjusted percentages estimated from multivariable logistic regression model that controlled for age, gender, education, and marital status. Solid lines represent the MHAS cohort, and dashed lines represent the HEPESE cohort. HEPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly; MHAS = Mexican Health and Aging Study.

Significant increases in the adjusted percentage for hypertension and ADL difficulty were observed in the MHAS. The adjusted percentage of hypertension increased from 43.7% to 49.5% (p = .01), and ADL difficulty increased from 37.2% to 44.3% (p < .01). Conversely, the adjusted percentage for arthritis in the MHAS decreased from 28.5% to 20.4% (p < .01). Additional analyses revealed that of the 120 MHAS participants who were interviewed in Wave I and survived to Wave III, 23 participants reported that they had been diagnosed with arthritis during the 2001 Wave but reported that they had not been diagnosed with arthritis during the 2012 Wave. The percentage of arthritis in the MHAS from 2000–2001 to 2010–2012 observation periods did not change substantially when these 23 participants were excluded from the analysis (25.9% 2000–2001 to 21.3% 2010–2012). No significant changes in the adjusted prevalence for diabetes (14.1% 2000–2001 to 16.4% 2010–2012), heart attack (6.3% 2000–2001 to 5.2% 2010–2012), or stroke (4.5% 2000–2001 to 4.8% 2010–2012) were observed in the MHAS.

Discussion

This study presents new evidence that there are significant differences between very old Mexican and Mexican American adults for self-reported health conditions. In 2000–2001, HEPESE participants had significantly greater odds of reporting having been diagnosed with diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, and stroke compared with MHAS participants. In 2010–2012, participants of the HEPESE had significantly higher odds to report having been diagnosed with all health conditions compared with participants of the MHAS. Also, the adjusted percentage of diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, stroke, and ADL difficulty increased among Mexican Americans from 2000–2001 to 2010–2012. The adjusted percentage of hypertension and ADL difficulty increased significantly over the same time period for Mexican adults, but the percentage of diabetes and stroke remained consistent, and the percentage of arthritis decreased. No significant changes in the percentage of heart attack were detected in the HEPESE or MHAS.

The higher odds for self-reported health conditions among Mexican Americans compared with Mexicans may be due to the disparities in health care access in Mexico. According to the World Health Organization, the physician density in Mexico is 20 physicians per 10,000 people, which is consistent with the 26 physicians per 10,000 people in the United States (World Health Organization, 2009). However, in the 1990s the poorest regions of Mexico had fewer than five physicians per 10,000 people and 1 hospital bed per 10,000 people, whereas the wealthiest regions of Mexico had an estimated 20 physicians per 10,000 people and 15 hospital beds per 10,000 people (Lozano et al., 2001). The substantial health care reform in Mexico has begun to reduce these disparities, but nearly 50% of the Mexican population in 2012 had no effective access to health care services (Gutierrez, Garcia-Saiso, Dolci, & Hernandez Avila, 2014). The limited access to health care in Mexico, especially in poor regions of Mexico, may contribute to an underreporting of health conditions because older adults with an underlying health condition who have not seen a physician in several years will not have received a diagnosis even though they may have the disease. The differences in access to health care may also result in Mexican Americans living longer with chronic health conditions compared with older Mexicans with the same condition. This may contribute to the differences in life expectancy after age 65, which in Mexico are 16.7 years for males and 18.5 years for females (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2013) compared with 18.8 years for male Mexican Americans and 22.0 years for female Mexican Americans (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). However, survival differences between the MHAS and HEPESE could not be assessed in the present study because the HEPESE cohort was replenished in 2004–2005, and these participants were included in the final sample.

In 2004, Mexico implemented a substantial reform in their health care system, and more than 50 million Mexicans who were previously uninsured gained health insurance by 2012 (Knaul et al., 2012). The health care reform has contributed to an increase in the treatment for hypertension (Bleich, Cutler, Adams, Lozano, & Murray, 2007) and diabetes (Sosa-Rubi, Galarraga, & Lopez-Ridaura, 2009), a reduction in health care spending for families (Knaul et al., 2006), and greater access to health care throughout Mexico (Doubova, Perez-Cuevas, Canning, & Reich, 2015). The greater access to health care may contribute to an increase in the incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and similar chronic diseases because existing cases that had previously been undiagnosed may now be detected.

A second factor that may contribute to the higher odds for self-reported health conditions among Mexican Americans is differences in the patterns of care and diagnostic rates for chronic health conditions between Mexico and the United States. For example, low diagnostic rates among physicians in Mexico would result in an underreporting of chronic health conditions by participants in the MHAS. Conversely, high diagnostic rates for chronic health conditions among Mexican Americans would contribute to an overestimation of self-reported health conditions in the HEPESE.

The greatest difference between participants of the MHAS and HEPESE in the adjusted percentage of self-reported health conditions was for arthritis. This may reflect actual differences in the prevalence of arthritis in these populations, but it is important to note the influence that cultural differences, in the expectations for what type of health changes will occur with advancing age, may have on the prevalence of self-reported arthritis. Older Mexican adults may be less likely to report joint pain or soreness to a physician because these are believed to be normative changes that occur with advancing age. This will result in an underdiagnosis of arthritis in this population and may have contributed to the substantially higher prevalence of arthritis reported by participants of the HEPESE compared with the MHAS. The observed decline for arthritis from the 2000–2001 and 2010–2012 observation periods in the MHAS may be due, in part, to participants who were 71 to 79 years of age during the 2000–2001 observation who survived past 80 years of age having a low prevalence of arthritis. It should also be noted that the decrease in self-reported arthritis is similar to what is observed in the full MHAS cohort over the same time period. During Wave I, 19.5% of participants reported having been diagnosed with arthritis compared with 13.5% during Wave III. This provides evidence that a decrease in self-reported arthritis between Wave I and Wave III is not only among adults aged 80 and older. Data collection for the fourth Wave of the MHAS is ongoing, and these data can be used to conduct continued research on trends in self-reported arthritis in Mexico.

Considerable differences in the adjusted percentage of self-reported diabetes between participants of the MHAS and HEPESE were also detected. Prior research using data from the HEPESE has revealed that the prevalence of self-reported diabetes among Mexican Americans aged ≥75 has increased from 20.3% in 1993–1994 to 37.2% in 2004–2005 (Beard, AlGhatrif, Samper-Ternent, Gerst, & Markides, 2009). The International Diabetes Foundation has reported that the estimated prevalence of diabetes in Mexico among adults aged 20 to 79 in 2014 was 11.9% (Florencia et al., 2014). This prevalence estimate is similar to the adjusted percentage of self-reported diabetes for very old Mexican adults observed in the present study during the 2000–2001 and 2010–2012 observation periods. The increase in the prevalence of self-reported diabetes among older Mexican Americans may be due to better disease management and increased survival with chronic health conditions (Markides & Gerst, 2011). This may also contribute to the significantly higher adjusted prevalence of self-reported diabetes among very old participants of the HEPESE compared with the MHAS in the present study. Mexico has a high prevalence of pre-diabetes and undiagnosed cases of diabetes (Kumar, Wong, Ottenbacher, & Al Snih, 2016), and the recent expansion of the health care system in Mexico may result in an increase in the prevalence of self-reported diabetes because previously undiagnosed cases can be detected. Increased survival among older adults diagnosed with diabetes due to a greater proportion of the population receiving medical care may also contribute to an increase in the prevalence of self-reported diabetes in this population.

This study has important limitations that require discussion. First, health conditions were ascertained in both studies by self-report. This required a participant to have received a diagnosis from a physician or other health professionals. Therefore, estimated percentages for health conditions may have been underestimated because undiagnosed cases will be incorrectly classified. The HEPESE has ascertained direct measures for systolic and diastolic blood pressure during all observation waves, and Wave III of the MHAS collected blood samples from a subgroup of participants to ascertain HbA1c concentrations. These measures could have been used to identify additional cases of hypertension and diabetes. However, we chose to use only the self-reported measure for hypertension and diabetes as direct measures to identify undiagnosed cases were not collected consistently between the HEPESE and MHAS. In addition, participants may not correctly recall if he or she had received a diagnosis of a specific medical condition. This is particularly true for arthritis, which may be more prone to incorrect classification because this health condition is not as significant of a medical event as a stroke or heart attack.

A second limitation is that the MHAS and HEPESE were not initially designed to study differences between older Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The design and implementation of both studies were based on the social and cultural contexts of the sample populations, which may have contributed to differences in question wording and phrasing between the two studies. This is particularly true for how ADLs were measured in the MHAS and HEPESE. Question wording and phrasing can influence a participant’s responses to questions about ADL performance (Chan, Kasper, Brandt, & Pezzin, 2012; Wiener, Hanley, Clark, & Van Nostrand, 1990). MHAS participants were asked if they had difficulty completing an ADL because of a health problem, whereas HEPESE participants were asked if they needed help to complete an ADL and did not specify if the need for assistance was because of a health problem. Thus, the question wording of the MHAS may contribute to an underreporting of ADL difficulty in this cohort because participants who were unable to independently perform an ADL for a reason other than a health condition may respond no to the survey question. In addition, the threshold for ADL difficulty in the MHAS is less severe than in the HEPESE because the MHAS only required participants to have difficulty completing the activity, whereas the HEPESE requires participants to need help from a person or assistive device. This difference in the severity of ADL difficulty prevented us from directly comparing the percentage of participants who were identified as having ADL difficulties between the two cohorts.

Finally, participants with missing data for measures of self-reported health and ADLs were excluded from the final sample. This may influence how representative the final sample was of adults aged ≥80 in Mexico and Mexican Americans aged ≥80 in the United States and may limit the generalizability of the study findings. However, the number of participants excluded because of missing data is small and is unlikely to have a substantial effect on the final results. Also, differences in the socioeconomic, health, and functional characteristics of the replenished HEPESE cohort in 2004–2005 compared with participants in the 2000–2001 observation period may affect the representativeness of the final sample and generalizability of the study findings.

In summary, Mexican American adults aged ≥80 are more likely to report having been diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, heart attack, and stroke compared with Mexican adults aged ≥80. In addition, self-reported diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, stroke, and ADL difficulties have increased in the HEPESE, whereas hypertension and ADL difficulties have increased and self-reported arthritis has decreased in the MHAS. The differences in self-reported health between the HEPESE and MHAS may reflect overall poorer health among very old Mexican Americans compared with Mexicans, but the role that cultural factors, reporting biases, differences in access to health care, and the representativeness of the sample populations need to be considered. Additional research is necessary to determine whether the increased access to health care due to the considerable health care reform in Mexico will contribute to an increase in the detection of diabetes, hypertension, and related chronic conditions among very old Mexican adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (5T32AG000270-17, 2R01AG010939-21, and 5R1AG018016-10).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: Why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography. 2006;43:337–360. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E. United States Life Tables by Hispanic Origin. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: Implications for future research. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108:1330–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard HA, AlGhatrif M, Samper-Ternent R, Gerst K, Markides KS. Trends in diabetes prevalence and diabetes-related complications in older Mexican Americans from 1993–1994 to 2004–2005. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2212–2217. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Cutler DM, Adams AS, Lozano R, Murray CJ. Impact of insurance and supply of health professionals on coverage of treatment for hypertension in Mexico: Population based study. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.617616.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Borges G, Tancredi DJ, Saito N, Anderson H, Kravitz R, … Mora ME. Health selection among migrants from Mexico to the U.S.: Childhood predictors of adult physical and mental health. Public Health Reports. 2011;126:361–370. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KS, Kasper JD, Brandt J, Pezzin LE. Measurement equivalence in ADL and IADL difficulty across international surveys of aging: Findings from the HRS, SHARE, and ELSA. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67:121–132. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Doubova SV, Perez-Cuevas R, Canning D, Reich MR. Access to healthcare and financial risk protection for older adults in Mexico: Secondary data analysis of a national survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007877. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florencia A, Alex B, Ho Nam C, Gisela D, Sheree D, Trisha D, … David W. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6. Basel, Switzerland: International Diabetes Federation; 2014. Retrieved from https://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/EN_6E_Atlas_Full_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez MH. A demographic portrait of Mexican-origin Hispanics in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Research Hispanic Center; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/05/2013-04_Demographic-Portrait-of-Mexicans-in-the-US.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JP, Garcia-Saiso S, Dolci GF, Hernandez Avila M. Effective access to health care in Mexico. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:186. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Angel Centeno M. The Lopsided Continent: Inequality in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, Arreola-Ornelas H, Mendez-Carniado O, Bryson-Cahn C, Barofsky J, Maguire R, … Sesma S. Evidence is good for your health system: Policy reform to remedy catastrophic and impoverishing health spending in Mexico. Lancet. 2006;368:1828–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, Gonzalez-Pier E, Gomez-Dantes O, Garcia-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Llorens M, … Frenk J. The quest for universal health coverage: Achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Wong R, Ottenbacher KJ, Al Snih S. Prediabetes, undiagnosed diabetes, and diabetes among Mexican adults: Findings from the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2016;26:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariscy JT, Hummer RA, Hayward MD. Hispanic older adult mortality in the United States: New estimates and an assessment of factors shaping the Hispanic paradox. Demography. 2015;52:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0357-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Zurita B, Franco F, Ramirez T, Hernandez P, Torres J. Mexico: Marginality, need and resource allocation at the county level. In: Evans T, editor. Challenging inequities in health: From ethics to action. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 272–295. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60(Spec No 2):68–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Gerst K. Immigration, aging and health in the United States. In: Settersen R, Angel J, editors. Handbook of sociology of aging. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Rudkin L, Angel RJ, Espino DV. Health status of Hispanic elderly. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, editors. Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. pp. 285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Brid JC, Krozer A. Inequality in Mexico. World Economics Association Newsletter. 2014;4:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus11.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at age 65 Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: Explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41:385–415. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Pinto-Aguirre G, Pelaez M. Demographic and health conditions of ageing in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:762–771. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel KV, Peek MK, Wong R, Markides KS. Comorbidity and disability in elderly Mexican and Mexican American adults: Findings from Mexico and the Southwestern United States. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:315–329. doi: 10.1177/0898264305285653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. Available from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Riosmena F, Wong R, Palloni A. Migration selection, protection, and acculturation in health: A binational perspective on older adults. Demography. 2013;50:1039–1064. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0178-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvin E, Parrinello CM, Sacks DB, Coresh J. Trends in prevalence and control of diabetes in the United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2010. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160:517–525. doi: 10.7326/M13-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa-Rubi SG, Galarraga O, Lopez-Ridaura R. Diabetes treatment and control: The effect of public health insurance for the poor in Mexico. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87:512–519. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Dias RH, Thomas KJ, Rivera JA, Carvalho N, Barquera S, … Ezzati M. Characterizing the epidemiological transition in Mexico: National and subnational burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:e125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Volume 1: Comprehensive Tables. 2015 Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2015_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic Population: 2010. Washington, DC: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener JM, Hanley RJ, Clark R, Van Nostrand JF. Measuring the activities of daily living: Comparisons across national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1990;45:S229–S237. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.s229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R, Michaels-Obregon A, Palloni A. Cohort profile: The Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu263. First published online: January 27, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R, Palloni A. Aging in Mexico and Latin America. In: Uhlenberg P, editor. International handbook of population aging. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2009. 2009 (97892-4-156381-9). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS09_Full.pdf.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2014. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112738/1/9789240692671_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]