Abstract

The characterization of the distribution of mutational effects is a key goal in evolutionary biology. Recently developed deep-sequencing approaches allow for accurate and simultaneous estimation of the fitness effects of hundreds of engineered mutations by monitoring their relative abundance across time points in a single bulk competition. Naturally, the achievable resolution of the estimated fitness effects depends on the specific experimental setup, the organism and type of mutations studied, and the sequencing technology utilized, among other factors. By means of analytical approximations and simulations, we provide guidelines for optimizing time-sampled deep-sequencing bulk competition experiments, focusing on the number of mutants, the sequencing depth, and the number of sampled time points. Our analytical results show that sampling more time points together with extending the duration of the experiment improves the achievable precision disproportionately compared with increasing the sequencing depth or reducing the number of competing mutants. Even if the duration of the experiment is fixed, sampling more time points and clustering these at the beginning and the end of the experiment increase experimental power and allow for efficient and precise assessment of the entire range of selection coefficients. Finally, we provide a formula for calculating the 95%-confidence interval for the measurement error estimate, which we implement as an interactive web tool. This allows for quantification of the maximum expected a priori precision of the experimental setup, as well as for a statistical threshold for determining deviations from neutrality for specific selection coefficient estimates.

Keywords: experimental design, experimental evolution, distribution of fitness effects, mutation, population genetics

MUTATIONS provide the fuel for evolutionary change, and their fitness effects critically influence the course and dynamics of evolution. The distribution of fitness effects (DFE) lies at the heart of many evolutionary concepts, such as the genetic basis of complex traits (Eyre-Walker 2010) and diseases (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2010), the rate of adaptation to a new environment (Gerrish and Lenski 1998; Orr 1998, 2005b), the maintenance of genetic variation (Charlesworth et al. 1995), and the relative importance of selection and drift in molecular evolution (Ohta 1977, 1992; Kimura 1979). Unsurprisingly, considerable effort has been devoted, both empirically (e.g., Sawyer et al. 2003; Sousa et al. 2012; Gordo and Campos 2013; Bernet and Elena 2015) and theoretically (e.g., Gillespie 1983; Orr 2005a; Martin and Lenormand 2006b; Connallon and Clark 2015; Rice et al. 2015), to assess the fraction of all possible mutations that are beneficial, neutral, or deleterious. Until recently, the two main approaches for assessing the DFE have been based either on the analysis of polymorphism and divergence data (Jensen et al. 2008; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2010; Schneider et al. 2011) or on laboratory evolution studies in which spontaneously occurring mutations are followed for many generations (Imhof and Schlötterer 2001; Rozen et al. 2002; Halligan and Keightley 2010; Frenkel et al. 2014). However, the complex action and interaction of evolutionary forces within and between individuals and the environment make accurate estimation of fitness effects of single mutations difficult (Orr 2009).

Recently, an alternative option to study mutational effects on a large scale has emerged from the field of biophysics: deep mutational scanning (DMS; Fowler et al. 2010; Hietpas et al. 2011; Fowler and Fields 2014). This approach is typically focused on a specific region of the genome for which a large library of mutants is created, through either random or systematic mutagenesis. The effects of the mutants are subsequently assessed by sequencing, with the readout yielding the relative frequencies of each mutant through time (obtained either directly or via sequence tags). This results in a high-precision snapshot of local mutational effects without the influence of genome-wide interactions (e.g., epistasis) and environmental fluctuations.

DMS provides various advantages over traditional approaches of deriving DFEs from polymorphism and laboratory-evolution data. First, it is not confounded by sampling bias (i.e., lethal mutations can also be observed) because the entire spectrum of preengineered or random mutations is introduced into a controlled and identical genetic background rather than waiting for mutations to appear and survive stochastic loss (Rokyta et al. 2005; Orr 2009). Second, the short timeframe of the experiment and the large library size minimize the influence of secondary mutations, which eliminates the challenges imposed by epistasis and linked selection. Finally, bulk competition ensures that all mutants experience the same environment.

A DMS approach termed EMPIRIC (Hietpas et al. 2011, 2012) has been most prevalently studied with respect to estimation of the DFE and its application to evolutionary questions. EMPIRIC allows simultaneous estimation of the fitness of systematically engineered mutations in a given protein region. Mutants are constructed by transformation of preconstructed plasmid mutant libraries, each representing one of all total point mutations from the focal protein region; these then undergo bulk competition for a number of generations. Fitness is determined by assessing relative growth rates from the relative abundance of each mutant, which is obtained from deep sequence data for a number of time points.

To date, EMPIRIC has been applied to yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) to illuminate the DFE of all point mutations in Ubiquitin (Roscoe et al. 2013) and Hsp90 (Hietpas et al. 2011) across different environments, to quantify the amount and strength of epistatic interactions within a region of Hsp90 (Bank et al. 2015), and to assess a large intragenic fitness landscape in Hsp90. Recently, this approach has been extended to human influenza A virus to study the DFE in a region of the Neuraminidase protein containing a known drug-resistant locus. This opens the door for studying the mechanistic features underlying drug resistance and for determining potential future resistance mutations in viral populations (Jiang et al. 2015).

It has been demonstrated that the EMPIRIC approach is highly reproducible across replicate experiments and shows strong correspondence with selection coefficient estimates from binary competitions (Hietpas et al. 2011, 2013), resulting in precise estimates of selection coefficients (Bank et al. 2014). However, the attainable precision strongly depends on the experimental setup, in particular on the number of mutants considered, the number of time samples taken, and the sequencing depth. Furthermore all these factors need to be determined before the experiment and are constrained by the scientific question at hand and additional limitations imposed by time and budget. The aim of this article is to provide a statistical framework for a priori optimization of the experimental setup for future DMS studies (for an alternative approach see Kowalsky et al. 2015).

Our model was originally inspired by the EMPIRIC approach, but our predictions can be readily applied to any experiment that meets the following requirements (see Table 1 for further examples):

Table 1. List of published DMS studies assessing mutant growth rates in accordance with our statistical model, arranged by number of time points sampled.

| Reference | No. of time points | No. of mutants | Total no. of sequence reads (millions) | Reproducibility (if reported) | Summary of reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hietpas et al. (2013) | 6 or 7 | 568 | 30 | for full replicates | Beneficial single substitutions in Hsp90 of yeast under altered environments |

| Jiang et al. (2013) | 6 or 7 | 568 | 34 | for full replicates | Interaction of expression and single substitutions on DFE of yeast Hsp90 |

| Puchta et al. (2016) | 5–7 | ≈60,000 | 545.7 | Network of epistatic interactions in yeast small nucleolar RNA | |

| Roscoe et al. (2013) | 6 | 1,530 | 21 | for full replicates | Functional biophysics of single substitutions in ubiquitin of yeast |

| Hietpas et al. (2011) | 3 or 7 | 568 | 26 | for full replicates | DFE of single substitutions for a short region of Hsp90 in yeast |

| Bank et al. (2015) | 5 | 1,015 | 21.6 | Credibility intervals (figure 6B) | DFE of epistatic substitutions in Hsp90 of yeast |

| Wu et al. (2013) | 3 | >400 | >0.002 | NA | Compensatory single substitutions for neuraminidase mutant of influenza |

| Li et al. (2016) | 2 | 65,537 | 685.5 | mean across 15 pairs of biological replicates | Fitness landscape of a transfer RNA gene in yeast |

| Jiang et al. (2015) | 2 | 475 | 20.5 | for full replicates | Biophysics of single substitutions in influenza neuraminidase with antiviral |

| Roscoe and Bolon (2014) | 2 | 1,617 | 30 | for full replicates | Biophysics of single ubiquitin substitutions on E1 activity and yeast fitness |

| Melnikov et al. (2014) | 2 | 4,993 | 33.2 | for full replicates | Biophysics of single substitutions in APH(3′)II in Escherichia coli with antibiotics |

| Kim et al. (2013) | 2 | 29,708 | 90.2 | NA | Biophysics of single substitutions in yeast Deg1 protein degradation signal |

| Melamed et al. (2013) | 2 | 110,745 | 186.5 | NA | Biophysics of single and multiple substitutions in Pab1 RRM of yeast |

| Klesmith et al. (2015) | 2 | 9,219 | 5.8 | Reproducibility plot | Biophysics of levoglucosan consumption rate in E. coli |

All studied mutants are present at large copy number at the beginning of the experiment (such that all mutants will be sampled sufficiently at later time points; usually on the order of ).

The population size is always kept smaller than the carrying capacity (e.g., through serial dilution or in a chemostat), such that mutants grow approximately exponentially (i.e., log-linearly) throughout the experiment.

Population size and sample size (for sequencing or in case of serial passaging) are large compared with the number of mutants and sequencing depth.

Populations are sampled by deep sequencing (or fluorescence counting) at two or more time points, and individual mutant frequencies are assessed either directly or via sequence tags.

Thus, the statistical guidelines derived in the following can in principle be directly applied to experiments, using new genome-editing approaches based on CRISPR/Cas9 (Jinek et al. 2012), ZFN (Chen et al. 2011), and TALEN (Joung and Sander 2013), which constitute particularly exciting and promising new means for assessing the selective effects of new mutations (i.e., the DFE), but equally pertain to traditional binary competition experiments to assess relative growth rates. Note however, that DMS studies in which the functional capacity of a (mutant) protein (i.e., the protein fitness) cannot be directly related to organismal fitness (for a recent review on the topic see Boucher et al. 2016) do not adhere to the statistical framework presented here. Examples include recent DMS studies, which were based on fluorescence (as in Sarkisyan et al. 2016), antibiotic resistance (e.g., Jacquier et al. 2013; Firnberg et al. 2014), and binding selection using protein display technologies (Fowler et al. 2010; Whitehead et al. 2012; Olson et al. 2014).

Here, we derive analytical approximations for the variance and the mean squared error (MSE) of the estimators for the selection coefficients obtained by (log-)linear regression. We describe how measurement error decreases with the number of sampling time points and the number of sequencing reads and how increasing the number of mutants generally increases the MSE. Based on these results, we derive the length of the -confidence interval as an a priori measure of maximum attainable precision under a given experimental setup. Furthermore, we demonstrate that sampling more time points together with extending the duration of the experiment improves the achievable precision disproportionately compared with increasing the sequencing depth. However, even if the duration of the experiment is fixed, sampling more time points and clustering these at the beginning and the end of the experiment increases experimental power and allows for efficient and precise assessment of selection coefficients of strongly deleterious as well as nearly neutral mutants. When applying our statistical framework to a data set of 568 engineered mutations from Hsp90 in S. cerevisiae, we find that the experimental error is well predicted as long as the experimental requirements (see above) are met. To ease application of our results to future experiments, we provide an interactive online calculator (available at https://evoldynamics.org/tools).

Model and Methods

Experimental setup

We consider an experiment assessing the fitness of K mutants that are labeled by . Each mutant is present in the initial library at population size and grows exponentially at constant rate Consequently, the number of mutants of type i at time t is given by For convenience, we measure time in hours. Growth rates can easily be rescaled to where denotes the growth rate per generation. At each sampling time point sequencing reads are drawn from a multinomial distribution with parameters D (sequencing depth) and where is the relative frequency of mutant i in the population at time t. Accordingly, τ and denote the number of samples and the duration of the experiment, respectively. Note that for notational convenience, we omit the subscript in t to denote any element in t. For illustrative purposes, we present our results under the assumption that T equally spaced time points are sampled, such that and in particular and Note that, with this definition, increasing the number of sampling time points (T) increases the actual numbers of samples taken (τ) and the duration of the experiment (). The separate effects of τ and will be discussed subsequently (notation and definitions in Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of notation and definitions.

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| K | No. of mutants |

| D | Total no. of reads per sampling time point (sequencing depth) |

| Initial population size of mutant i | |

| (Exponential) growth rate of mutant i | |

| No. of mutants of type i at time t | |

| Vector of the observed no. of sequencing reads sampled at time t | |

| Relative frequency of mutant i at time t | |

| τ | No. of samples taken |

| Duration of the experiment | |

| T | No. of sampling time points |

| Selection coefficient of mutant i |

Furthermore, let denote the random vector of the number of sequencing reads sampled at time t. Without loss of generality, we denote the wild-type reference (or any chosen reference type) by and set its growth rate to 1 (i.e., ). Thus, mutant growth rates are measured relative to that of the wild type. Accordingly, the selection coefficient of mutant i with respect to the wild type is given by

Estimators for the selection coefficients are then obtained from linear regression, based on log ratios of the number of sequencing reads over the different sampling time points (but see Bank et al. 2014, for a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo approach). The corresponding linear model can then be written as

| (1) |

where is the (transformed) observation variable, C is a constant (i.e., the intercept), and denotes the regression residual.

In the following, we derive an estimator that uses the log ratios of the number of reads of mutant i over the number of reads of the wild type as dependent variables in a linear regression. We call this method the wild-type (WT) approach. In Supplemental Material, File S2, we derive and analyze an alternative selection coefficient estimator that is based on log ratios of the number of mutant reads with respect to the total number of sequencing reads, which we call the total (TOT) approach. This estimator has previously been used for detecting outliers within the experimental setup considered in Bank et al. (2014).

Estimation of selection coefficients

Ultimately, we want to calculate the mean of the log ratios of the number of sequencing reads for mutant i over the number of wild-type sequencing reads, By noting that is binomially distributed [for every mutant ] and using the Delta method (for derivation see File S1; see also Hurt 1976; Casella and Berger 2002), we derive

| (2) |

such that an estimator for can be obtained by applying the ordinary least-squares (OLS) method on the linear regression model

| (3) |

where denotes the regression residual using the WT approach (as opposed to the TOT approach; see also File S2). Note that the additive term within the logarithm ensures that the logarithm is always well defined and was added solely for mathematical convenience.

Simulation of time-sampled deep sequencing data

To validate analytical results, we simulated time-sampled deep sequencing data (implemented in C++; available upon request). We assumed that mutant libraries were created perfectly, such that the initial population size was identical for all mutants and, accordingly, for all Selection coefficients were independently drawn from a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 0.1. To test the robustness of these assumptions we performed additional simulations where initial population sizes were drawn from a log-normal distribution [i.e., ] reflecting empirical distributions of inferred initial population sizes. Furthermore, selection coefficients were also drawn from a mixture distribution

| (4) |

where (Figure S1). For a given number of sampling time points T and sequencing depth D, the number of mutant sequencing reads was drawn from a multinomial distribution with parameters D and for each sampling point. Selection coefficient estimates were then obtained by fitting the linear model by means of OLS. Finally, the accuracy of the parameter estimates was assessed by computing the MSE,

| (5) |

and the deviation (DEV)

| (6) |

Note that we have omitted the hat over the MSE and DEV for notational convenience. If not stated otherwise, statistics were calculated over simulated experiments for each set of parameters.

Data availability

The empirical data used in Figure 4 have been downloaded from Dryad, DOI: 10.5061/dryad.nb259 (data from Hietpas et al. 2013).

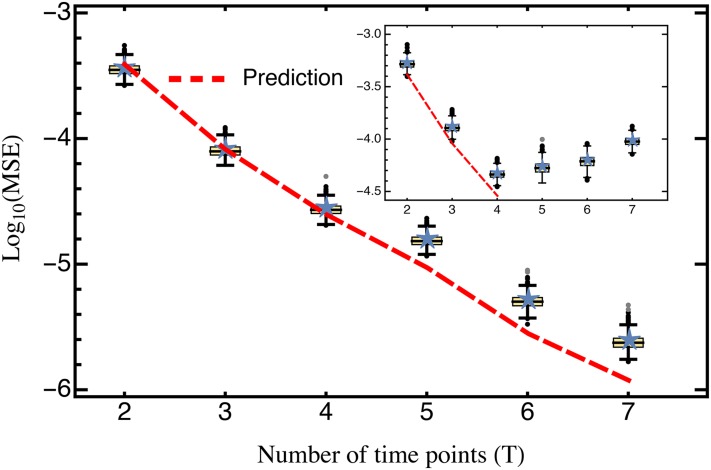

Figure 4.

Comparison of the predicted mean squared error (Equation 10; red) against the average mean squared error (blue stars) obtained from cross-validation data sets. Only mutants with an estimated selection coefficient larger than the intermediate between the estimated mean synonym and the estimated mean stop codon selection coefficient were considered. The inset shows the MSE calculated for all mutants. The MSE is presented on log scale. Other parameters: Alternatively, in the presence of strongly deleterious mutants a Poisson regression may be used for estimating growth rates (see Figure S7).

Results and Discussion

The aim of this article is to provide a statistical framework for a priori optimization of the experimental setup for future DMS studies. As such, our primary interest lies in the quantification of the MSE and its dependence on the experimental setup. We first deduce analytical approximations for the variance and the MSE of the estimators for the selection coefficient and compare these with simulated data. We then derive approximate formulas for the length of the confidence interval of the estimates and the mean absolute error (MAE), which can be used to assess the expected precision of the estimates. For each of these steps, we discuss the consequences of relaxing some of the above assumptions along with potential extensions of the model. Finally, we apply our statistical framework to experimental evolution data of 568 engineered mutations from Hsp90 in S. cerevisiae and show that our model indeed captures the most prevalent source of error (i.e., error from sampling).

Approximation of the mean squared error

Generally, the MSE of an estimator (for parameter θ) is given by

(see section 7.3.1 of Casella and Berger 2002). Since (i.e., the mean of the regression residual is zero, implying that is an unbiased estimator; Figure S2), it is sufficient to analyze to assess For ease of notation, and since all results in the main text are derived using the wild-type approach, we omit the WT index from here on. Taking the variance of Equation 3 implies

| (7) |

which, by applying the Delta method (see File S1) and using Equation S5 in File S1 together with Equations S4 and S6 in File S1 can be approximated by

| (8) |

Note that the residuals are heteroscedastic [i.e., their variance is time dependent; the relative mutant frequencies change during the course of the experiment]. Hence, there is no general closed-form expression of the variance of However, by making the simplifying assumption of homoscedasticity [i.e., and for all t], we obtain

| (9) |

where the dependence on time has been dropped for ease of notation. Note that omitting the covariance term implicitly assumes that the number of mutants K is sufficiently large (i.e., and are small). We discuss the effect of assuming homoscedastic error terms below. Equation 9 shows that decreases monotonically with increasing sequencing depth and increasing relative proportions of the wild-type and focal mutants.

Using existing theory on variances of slope coefficients in a linear regression framework with homoscedastic error terms (e.g., see section 11.3.2 in Casella and Berger 2002), the variance of the selection coefficient estimate is given by

| (10) |

which is our first main result.

Using that sampling times are assumed to be equally spaced, Equation 10 can further be rewritten as

| (11) |

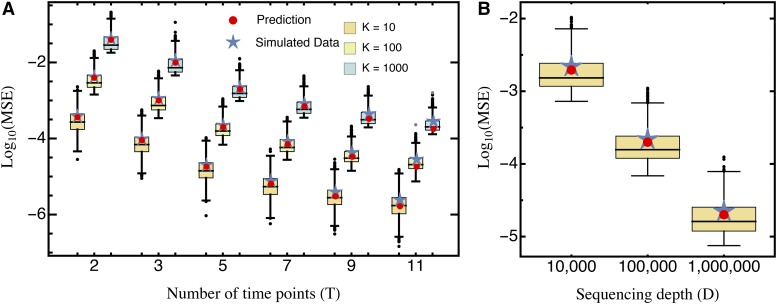

which shows that the MSE decreases cubically with the number of time points T (Figure 1). Thus, sampling additional time points (i.e., taking more samples and thereby extending the duration of the experiment) drastically increases the precision of the measurement.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the predicted mean squared error (Equation 10; red circles) and the average mean squared error (blue stars), obtained from simulated data sets for (A) different numbers of sampling time points T and mutants K, for sequencing depth and (B) different sequencing depth D, with fixed Boxes represent the interquartile range (i.e., the 50% C.I.), whiskers extend to the highest/lowest data point within the box 1.5 times the interquartile range, and black and gray circles represent close and far outliers, respectively. Results are presented on log scale.

Our approximation generally performs very well across the entire parameter space. Although we assumed that the relative abundance of all mutants remains roughly constant with time (i.e., neglecting that error terms are heteroscedastic), the (small) absolute error of our approximation remains constant across time points (Figure S3A). Deviations from homoscedasticity increase as more and later time points are sampled, as shown by the relative error (Figure S3B). This is also reflected by the deviation between the predicted MSE and the true average MSE obtained from the simulated data (Figure 1). For realistic experimental durations, however, compared to the experimental error (due to sampling) this approximation error is negligible.

Uneven sampling schemes:

To obtain a closed formula for the decay in the measurement error with the number of time samples T (Equation 11), we assumed equally spaced sampling times. The observed decay remains cubic relative to the number of time points also when samples are not taken at equally spaced time points. Furthermore, Equation 10 informs about the optimal sampling scheme to use to minimize measurement error: For fixed sequencing depth and number of mutants, the MSE is minimized when the sum of squared deviations of the sampling times from their mean is maximized. In other words, to minimize the measurement error one should sample in two sampling blocks, one at the beginning and another at the end of the experiment instead of sampling throughout the experiment, or, if time and resources allow, create full two-time-point replicates [e.g., is better than see also the interactive demonstration tool provided online].

Duration and sampling density of the experiment:

Equation 11 implies that the MSE decreases cubically when both more samples are taken and the duration of the experiment is extended. However, extending the experiment indefinitely is impossible, both because of experimental constraints and because secondary mutations will begin to affect the measurement. Hence, the possible duration of an experiment under a given condition may be a (fixed) short time (e.g., <20 yeast generations for EMPIRIC). To separate the effects of taking more samples τ from those of extending the duration of the experiment —which are combined in T in the normal model setup (see Model and Methods)—Equation 11 can be rewritten as

| (12) |

Thus, when the duration of the experiment is held constant, measurement error decays linearly as τ (i.e., the number of sampling points) increases. Conversely, when extending the duration of experiment, the MSE decreases quadratically. This result suggests that the experimental duration should always be maximized under the constraints that mutants grow exponentially and population size is much smaller than the carrying capacity. How long both of these assumptions are met depends on each individual mutant’s selection coefficient (or growth rate) and its initial frequency. Accordingly, there is no universal “optimal” duration of the experiment. For example, the frequency of strongly deleterious mutations in the population generally decreases quickly, such that the phase where they show strict exponential growth is short and does not span the entire duration of the experiment. Furthermore, mutations might be lost from the population before the experiment is completed. Thus, when sampling two time points that extend over a long experimental time, growth rates for strongly deleterious mutations can be substantially overestimated (see also Contribution of additional error: Data application).

Conversely, for mutations with small (i.e., wild-type-like) selection coefficients, increasing the duration of the experiment considerably improves the precision of the estimates. Specifically, to infer deviations from the wild type’s growth rate the (expected) log ratio of the number of mutant sequencing reads over the number of wild-type sequencing reads (i.e., the ratio of relative frequencies between mutant and wild-type abundance) needs to change consistently with time (i.e., either increase or decrease; Equation 2). However, changes in the log ratios will be small if the duration of the experiment is short, and even if there are slight shifts, sequencing depth D needs to be large enough such that they are not washed out by sampling.

Thus, beyond the linear improvement on the MSE that comes with increasing τ, sampling more time points can be an efficient strategy to capture the entire range of selection coefficients (i.e., strongly deleterious and wild-type-like mutants). Specifically, sampling in two blocks (one at the beginning and another at the end of the experiment as suggested above) would allow using different depending on the underlying selection coefficient, which could be determined by a bootstrap leave-p-out cross-validation approach (for details see Contribution of additional error: Data application). For example, the first sampling block could be used for strongly deleterious mutations, whereas all sampled time points could be used for the remaining mutations, reducing error due to overestimation of strongly deleterious selection coefficients and increasing statistical power to detect differences from wild-type-like growth rates.

Library design and the number of mutants:

Increasing the number of mutants K reduces the number of sequencing reads per mutant and hence which explains the approximately linear increase of the MSE with K (Figure 1). Crucially, we assumed that the initial mutant library was balanced, such that all mutants were initially present at equal frequencies. In practice this is hardly ever the case and previous analyses have shown that initial mutant abundances instead follow a log-normal distribution (Bank et al. 2014). Taking this into account, we find that unbalanced mutant libraries, as expected from Equation 9, introduce an error due to the higher variance terms resulting from the generally lower (Figure S5). This error can be avoided by using the estimated relative mutant abundance, in Equation 9 (Figure S5).

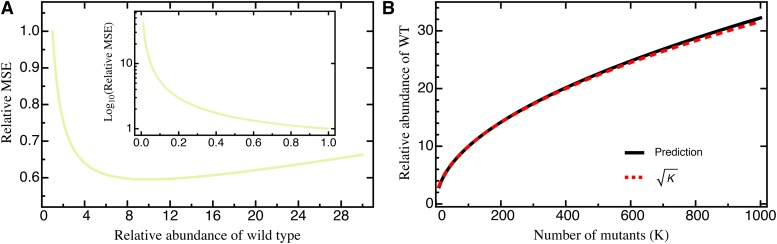

The additional—although practically inevitable—error introduced by variance in mutant abundance indicates that library preparation is an important first step for obtaining precise estimates. In fact, Equation 9 suggests that the measurement precision increases with the relative abundance of the wild type (such that the second term in Equation 9 decreases). However, this results in a trade-off because increasing wild-type abundance results in a decrease of the abundance of all other mutants, which leads to an increase of the first term in Equation 9. Assuming that increasing the relative abundance of the wild type reduces the relative abundance of all mutants equally (i.e., for all ), we find that precision is maximized by increasing the wild-type abundance by a factor proportional to (analytical result not shown; Figure 2). This way, the MSE can be reduced by compared to the MSE with equal proportions of all mutants. Most importantly, however, if wild-type abundance is low (i.e., ), the error increases substantially (i.e., >10-fold; see Figure 2A, inset).

Figure 2.

(A) The relative MSE as a function of the relative abundance of the wild type, i.e., for The inset shows results for where the y-axis has been put on log scale. The abundance of all other (except the wild type) is assumed to scale proportionally. (B) The relative wild-type abundance that minimizes the MSE as a function of the number of mutants K. An explicit formula (given by the black line) is not shown due to complexity, but can well be approximated by Either prediction is based on Equation 10. Other parameters:

Sequencing depth and its fluctuations:

The MSE decreases approximately linearly with the sequencing depth D (Figure 1), because the number of reads per mutant increases. As long as D is independent of the number of mutants K in the actual experiment, it can simply be treated as a rescaling parameter; hence, qualitative results are independent of the actual choice of D. Similarly, the variance of the estimated MSE decreases approximately quadratically with sequencing depth and increases quadratically as the number of mutants increases (Figure 1).

Although we here treat the sequencing depth D as a constant parameter, it will in practice vary between sampling time points. Thus, D should rather be interpreted as the (expected) average sequencing depth taken over all time points. In particular, compared to a fixed sequencing depth, variance in D introduces an additional source of error (due to increased heteroscedasticity), although deviations from the predicted to the observed mean MSE remain roughly identical (Figure S6). Our model can also account for other forms of sampling. For example, if the sample taken from the bulk competition is known to be smaller than the sequencing depth, its size should be used as D in the precision estimates.

Shape of the underlying DFE:

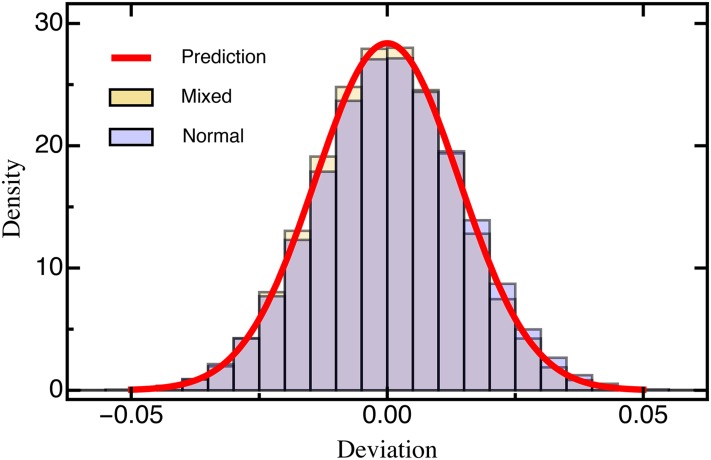

Our results remain qualitatively unchanged when selection coefficients are drawn from differently shaped DFEs. The assumed normally distributed DFE corresponds to theoretical expectations derived from Fisher’s geometric model [assuming that the number of traits under selection is large (Martin and Lenormand 2006a; Tenaillon 2014)]. DFEs inferred from experimental evolution studies, however, are typically characterized by an approximately exponential tail of beneficial mutations and a heavier tail of deleterious mutations (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Bank et al. 2014) that roughly follows a (displaced) gamma distribution (Martin and Lenormand 2006a; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2010). To account for this expected excess of deleterious mutations in the DFE (reviewed by Bataillon and Bailey 2014), we used a mixture distribution that resulted in a highly skewed DFE. For this, beneficial mutations () were drawn from an exponential distribution and deleterious mutations were given by the absolute value drawn from a Gaussian distribution (Figure S1; see Model and Methods for details). Even with this highly skewed DFE, we did not find changes in either the MSE (Figure S4) or the deviation (Figure 3), indicating that our results are robust across a range of realistic DFEs.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the deviation (Equation 6) between the estimated and true selection coefficients drawn from either a normal distribution or a mixture distribution (for details see Model and Methods) based on simulated data sets each. The red line is the prediction based on Equation 10. Other parameters:

An alternative normalization:

In File S2, we analyze and discuss an alternative estimation approach based on the log ratios of the number of mutant reads over the sequencing depth D (as opposed to a single reference/wild type) that was proposed in Bank et al. (2014) and called the TOT approach. Although the TOT approach can improve results for very noisy data (i.e., if T or D is small; File S2, Figures A–D), its estimates are generally biased. The bias increases with the number of time points and overrides the smaller variance in residuals (see Equation 9 and File S2, Equation S8). Thus, application of the TOT approach is recommended only under special circumstances, e.g., under the suspicion of outlier measurements in the wild type (as in the case of Bank et al. 2014).

Confidence intervals, precision, and hypothesis testing

One way of quantifying the precision of the estimated selection coefficient is obtained using Jensen’s inequality (see section 6.6 of Williams 1991), which yields an upper bound for the MAE,

| (13) |

where, in the last line, we have again assumed that sampling times are equally spaced. Thus, the MAE is simply the square root of the MSE.

Alternatively, using central limit theorem arguments (Rice 1995), it can be shown that for a fixed mutant i the estimated selection coefficient asymptotically follows a normal distribution (Figure 3 and Figure S2). The upper and lower bounds of the -confidence interval with significance level α for are then given by

| (14) |

where denotes the quantile of the standard normal distribution. The length of the -confidence interval, can be used as an intuitive a priori measure for the precision of the estimated selection coefficient. Formally, let denote the length of the -confidence interval. Setting and using Equation 10, we obtain the approximation

| (15) |

where we assumed Equation 15 shows that the sequencing depth D and the number of mutants K are inversely proportional. Similar to Equation 10, the number of time points T enters cubically.

Furthermore, Equation 14 can be used to define the upper and lower bounds of the region of rejection of a two-sided Z-test with, for instance, null hypothesis (or more generally any other null hypothesis ). The Z-statistic is then given by

| (16) |

(see Chap. 8 in Sprinthall 2014). This statistic can be applied to existing data to test whether a mutant has an effect different from the wild type. In addition, we can use this statistic to determine the maximum achievable statistical resolution of a planned experiment.

Optimization of experimental design

Equation 10 suggests that the measurement error modeled here could in theory be eliminated entirely by sampling (infinitely) many time points. In practice, the attainable resolution of the experiment is also limited by technical constraints imposed by the experimental details and by sequencing error and by the available manpower and budget. To further improve the experimental design taking the latter two factors into account, we can integrate our approach into an optimization problem, using a cost function As an example, we define

| (17) |

where denotes the personnel costs over the duration of the experiment, denotes the sequencing costs per sampled time point, and α and β scale the associated error costs given by Equation 12 (Boyd and Vandenberghe 2004). The optimization problem is solved by minimizing

| (18a) |

under constraints

| (18b) |

| (18c) |

| (18d) |

| (18e) |

which yields the maximum tolerable error while minimizing the total experimental costs. An illustrative example is given in File S3.

Contribution of additional error: Data application

An important limitation of our model is that it does not consider additional sources of experimental error. Therefore, any results presented here should be interpreted as upper limits of the attainable precision. In particular, sequencing error (dependent on the sequencing platform and protocol used) is expected to affect the precision of measurements. However, if the additional error is nonsystematic (i.e., random), it will not change the results qualitatively, but solely add an additional variance to the measurement.

To assess the influence of additional error sources on the validity of our statistical framework, we reanalyzed a data set of 568 engineered mutations from Hsp90 in S. cerevisiae grown in standard laboratory conditions (i.e., 30°; for details see Bank et al. 2014). We estimated the initial population size and the selection coefficient for each mutant, using the linear-regression framework discussed here. With respect to the experimental parameters (i.e., number and location of sampling points, sequencing depth) and our proposed model, we simulated bootstrap data sets. We assessed the accuracy of our selection coefficient estimates by calculating the MSE between the selection coefficient estimates obtained from the bootstrap data sets and those obtained from the experimental data, which serve as a reference for the “true” (but unknown) selection coefficient. To quantify the effect of the number of sampling time points, we used a leave-p-out cross-validation approach, successively dropping sampling time points (Geisser 1993).

For the complete data set, our prediction holds only when the number of time points considered is small. Conversely, with more than four time samples, the MSE even slightly increases with the number of sampling points (Figure 4, inset). However, when strongly deleterious mutations (i.e., those with a selection coefficient closer to that of the average stop codon than to the wild type; see also Bank et al. 2014) are excluded from the analysis, the MSE is very well predicted by Equation 10 for any number of time points (Figure 4). Two model violations may well explain the observed pattern when deleterious mutations are included. First, the frequency of strongly deleterious mutations in the population decreases quickly and does not show strictly exponential growth (figure S2 in Bank et al. 2014), especially for later time points. Second, these mutations might not be present in the population over the entire course of the experiment. Sequencing error will then create a spurious signal, feigning and extending their “presence,” thus biasing the results. The bootstrap approach utilized here could in principle be used to determine the time points that should be considered for the estimation of strongly deleterious mutations and to generally test for model violations. Indeed, Figure 4 demonstrates that our model captures the most prevalent source of error (i.e., error from sampling) when strongly deleterious mutations are excluded.

Conclusion

The advent of sophisticated biotechnological approaches on a single-mutation level, combined with the continual improvement and reduction in costs of sequencing, presents us with an unprecedented opportunity to address long-standing questions about mutational effects and the shape of the distribution of fitness effects. An additional step toward optimizing results receives little attention: By systematically invoking statistical considerations ahead of empirical work, it is possible to quantify and maximize the attainable experimental power while avoiding unnecessary expenses, regarding both financial and human resources. Here, we present a thorough statistical analysis that results in several straightforward, general predictions and rules of thumb for the design of DMS studies, which can be applied directly to future experiments using a free interactive web tool provided online (https://evoldynamics.org/tools). We emphasize here three important and general rules that emerged from the analysis:

Increasing sequencing depth and the number of replicate experiments is good, but adding sampling points together with increasing the duration of the experiment is much better for accurate estimation of small-effect selection coefficients.

Preparation of a balanced library is the key to good results. The quality of selection coefficient estimates strongly depends on the abundance of the reference genotype: Always ensure that the frequency of the reference genotype is — “less is a mess.”

Clustering sampling points at the beginning and the end of the experiment increases experimental power and allows the efficient and precise assessment of the entire range of the distribution of fitness effects.

Although the statistical advice presented here is limited to experimental approaches that fulfill the requirements listed in the Introduction and focuses on the error introduced through sampling, our work highlights the promises that lie in long-term collaborations between theoreticians and experimentalists compared to the common practice of post hoc statistical consultation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivo Chelo, Inês Fragata, Isabel Gordo, Kristen Irwin, Adamandia Kapopoulou, and Nicholas Renzette for helpful discussion and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This project was funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and a European Research Council starting grant (to J.D.J.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: D. M. Weinreich

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.190462/-/DC1.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Literature Cited

- Bank C., Hietpas R. T., Wong A., Bolon D. N., Jensen J. D., 2014. A Bayesian MCMC approach to assess the complete distribution of fitness effects of new mutations: uncovering the potential for adaptive walks in challenging environments. Genetics 196: 841–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank C., Hietpas R. T., Jensen J. D., Bolon D. N., 2015. A systematic survey of an intragenic epistatic landscape. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32: 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataillon T., Bailey S. F., 2014. Effects of new mutations on fitness: insights from models and data. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1320: 76–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet G. P., Elena S. F., 2015. Distribution of mutational fitness effects and of epistasis in the 5′ untranslated region of a plant RNA virus. BMC Evol. Biol. 15: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, J. I., D. N. A. Bolon, and D. S. Tawfik, 2016 Quantifying and understanding the fitness effects of protein mutations: Laboratory vs. nature. Protein Sci. 25(7): 1219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S., and L. Vandenberghe, 2004 Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK/London/New York. [Google Scholar]

- Casella, G., and R. L. Berger, 2002 Statistical Inference, Vol. 2. Duxbury Press, Pacific Grove, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D., Charlesworth B., Morgan M. T., 1995. The pattern of neutral molecular variation under the background selection model. Genetics 141: 1619–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Pruett-Miller S. M., Huang Y., Gjoka M., Duda K., et al. , 2011. High-frequency genome editing using ssDNA oligonucleotides with zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Methods 8: 753–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connallon T., Clark A. G., 2015. The distribution of fitness effects in an uncertain world. Evolution 69: 1610–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., 2010. Genetic architecture of a complex trait and its implications for fitness and genome-wide association studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 1752–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Keightley P. D., 2007. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firnberg E., Labonte J. W., Gray J. J., Ostermeier M., 2014. A comprehensive, high-resolution map of a gene’s fitness landscape. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31: 1581–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D. M., Fields S., 2014. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nat. Methods 11: 801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D. M., Araya C. L., Fleishman S. J., Kellogg E. H., Stephany J. J., et al. , 2010. High-resolution mapping of protein sequence-function relationships. Nat. Methods 7: 741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel E. M., Good B. H., Desai M. M., 2014. The fates of mutant lineages and the distribution of fitness effects of beneficial mutations in laboratory budding yeast populations. Genetics 196: 1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S., 1993 Predictive Inference (Chapman & Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics & Applied Probability). Taylor & Francis. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish P. J., Lenski R. E., 1998. The fate of competing beneficial mutations in an asexual population. Genetica 102/103: 127–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. H., 1983. A simple stochastic gene substitution model. Theor. Popul. Biol. 23: 202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordo I., Campos P. R. A., 2013. Evolution of clonal populations approaching a fitness peak. Biol. Lett. 9: rsbl20120239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan D. L., Keightley P. D., 2010. Spontaneous mutation accumulation studies in evolutionary genetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40: 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hietpas R., Roscoe B., Jiang L., Bolon D. N. A., 2012. Fitness analyses of all possible point mutations for regions of genes in yeast. Nat. Protoc. 7: 1382–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietpas R. T., Jensen J. D., Bolon D. N. A., 2011. Experimental illumination of a fitness landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 7896–7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietpas R. T., Bank C., Jensen J. D., Bolon D. N. A., 2013. Shifting fitness landscapes in response to altered environments. Evolution 67: 3512–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt J., 1976. Asymptotic expansions of functions of statistics. Appl. Math. 21: 444–456. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof M., Schlötterer C., 2001. Fitness effects of advantageous mutations in evolving Escherichia coli populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 1113–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier H., Birgy A., Le Nagard H., Mechulam Y., Schmitt E., et al. , 2013. Capturing the mutational landscape of the beta-lactamase tem-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 13067–13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. D., Thornton K. R., Andolfatto P., 2008. An approximate Bayesian estimator suggests strong, recurrent selective sweeps in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Mishra P., Hietpas R. T., Zeldovich K. B., Bolon D. N. A., 2013. Latent effects of hsp90 mutants revealed at reduced expression levels. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Liu P., Bank C., Renzette N., Prachanronarong K., et al. , 2015. A balance between inhibitor binding and substrate processing confers influenza drug resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 428: 538–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., et al. , 2012. A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung J. K., Sander J. D., 2013. TALENS: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14: 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D., Eyre-Walker A., 2010. What can we learn about the distribution of fitness effects of new mutations from DNA sequence data? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 365: 1187–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I., Miller C. R., Young D. L., Fields S., 2013. High-throughput analysis of in vivo protein stability. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12: 3370–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M., 1979. Model of effectively neutral mutations in which selective constraint is incorporated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76: 3440–3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesmith J. R., Bacik J.-P., Michalczyk R., Whitehead T. A., 2015. Comprehensive sequence-flux mapping of a levoglucosan utilization pathway in E. coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 4: 1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalsky C. A., Klesmith J. R., Stapleton J. A., Kelly V., Reichkitzer N., et al. , 2015. High-resolution sequence-function mapping of full-length proteins. PLoS ONE 10: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Qian W., Maclean C. J., Zhang J., 2016. The fitness landscape of a tRNA gene. Science 352: 837–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G., Lenormand T., 2006a A general multivariate extension of Fisher’s geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60: 893–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G., Lenormand T., 2006b The fitness effect of mutations in stressful environments: a survey in the light of fitness landscape models. Evolution 60: 2413–2427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed D., Young D. L., Gamble C. E., Miller C. R., Fields S., 2013. Deep mutational scanning of an rrm domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(a)-binding protein. RNA 19: 1537–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov A., Rogov P., Wang L., Gnirke A., Mikkelsen T. S., 2014. Comprehensive mutational scanning of a kinase in vivo reveals substrate-dependent fitness landscapes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T., 1977. Molecular Evolution and Polymorphism. National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T., 1992. The nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23: 263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Olson C. A., Wu N. C., Sun R., 2014. A comprehensive biophysical description of pairwise epistasis throughout an entire protein domain. Curr. Biol. 24: 2643–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. A., 1998. The population genetics of adaptation: the distribution of factors fixed during adaptive evolution. Evolution 52: 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. A., 2005a The genetic theory of adaptation: a brief history. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6: 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. A., 2005b Theories of adaptation: what they do and don’t say. Genetica 123: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. A., 2009. Fitness and its role in evolutionary genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta O., Cseke B., Czaja H., Tollervey D., Sanguinetti G., et al. , 2016. Network of epistatic interactions within a yeast snoRNA. Science 352: 840–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D. P., Good B. H., Desai M. M., 2015. The evolutionarily stable distribution of fitness effects. Genetics 200: 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, J., 1995 Mathematical Statistics and Data Analysis (Duxbury Advanced Series, Ed. 1.). Duxbury Press. Belmont, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Rokyta D. R., Joyce P., Caudle S. B., Wichman H. A., 2005. An empirical test of the mutational landscape model of adaptation using a single-stranded DNA virus. Nat. Genet. 37: 441–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe B. P., Bolon D. N. A., 2014. Systematic exploration of ubiquitin sequence, e1 activation efficiency, and experimental fitness in yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 426: 2854–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe B. P., Thayer K. M., Zeldovich K. B., Fushman D., Bolon D. N. A., 2013. Analyses of the effects of all ubiquitin point mutants on yeast growth rate. J. Mol. Biol. 425: 1363–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen D. E., de Visser J. A. G. M., Gerrish P. J., 2002. Fitness effects of fixed beneficial mutations in microbial populations. Curr. Biol. 12: 1040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisyan K. S., Bolotin D. A., Meer M. V., Usmanova D. R., Mishin A. S., et al. , 2016. Local fitness landscape of the green fluorescent protein. Nature 533: 397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. A., Kulathinal R. J., Bustamante C. D., Hartl D. L., 2003. Bayesian analysis suggests that most amino acid replacements in Drosophila are driven by positive selection. J. Mol. Evol. 57: S154–S164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A., Charlesworth B., Eyre-Walker A., Keightley P. D., 2011. A method for inferring the rate of occurrence and fitness effects of advantageous mutations. Genetics 189: 1427–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa A., Magalhaes S., Gordo I., 2012. Cost of antibiotic resistance and the geometry of adaptation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29: 1417–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinthall R. C., 2014. Basic Statistical Analysis, Ed. 9 Pearson; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon O., 2014. The utility of Fisher’s geometric model in evolutionary genetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45: 179–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead T. A., Chevalier A., Song Y., Dreyfus C., Fleishman S. J., et al. , 2012. Optimization of affinity, specificity and function of designed influenza inhibitors using deep sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 30: 543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D., 1991 Probability with Martingales (Cambridge Mathematical Textbooks). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK/London/New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wu N. C., Young A. P., Dandekar S., Wijersuriya H., Al-Mawsawi L. Q., et al. , 2013. Systematic identification of h274y compensatory mutations in influenza A virus neuraminidase by high-throughput screening. J. Virol. 87: 1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The empirical data used in Figure 4 have been downloaded from Dryad, DOI: 10.5061/dryad.nb259 (data from Hietpas et al. 2013).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the predicted mean squared error (Equation 10; red) against the average mean squared error (blue stars) obtained from cross-validation data sets. Only mutants with an estimated selection coefficient larger than the intermediate between the estimated mean synonym and the estimated mean stop codon selection coefficient were considered. The inset shows the MSE calculated for all mutants. The MSE is presented on log scale. Other parameters: Alternatively, in the presence of strongly deleterious mutants a Poisson regression may be used for estimating growth rates (see Figure S7).