Abstract

Background and objectives

Interdialytic weight gain in patients on hemodialysis is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and increased mortality. The degree of interdialytic weight gain is influenced by sodium intake. We evaluated the effects of tenapanor (AZD1722 and RDX5791), a minimally systemically available inhibitor of the sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3, on interdialytic weight gain in patients with CKD stage 5D treated with hemodialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This phase 2, randomized, double–blind study (NCT01764854; conducted January to September of 2013) enrolled adults on maintenance hemodialysis with interdialytic weight gain ≥3.0% of postdialysis weight and ≥2 kg. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive tenapanor or placebo. The primary end point was change in mean interdialytic weight gain (percentage of baseline postdialysis weight) from baseline (mean across a 2-week run-in period) to week 4. In a subgroup of inpatients, 24-hour stool sodium and stool weight were assessed for 1 week.

Results

Sixteen patients received 1 week of inpatient treatment (tenapanor, eight; placebo, eight), and 72 patients received 4 weeks of treatment in an outpatient setting (tenapanor, 37; placebo, 35; completers: tenapanor, 31; placebo, 33). In the outpatient cohort, no significant effect on interdialytic weight gain was detected; least squares mean changes in relative interdialytic weight gain from baseline to week 4 were tenapanor, −0.26% (95% confidence interval, −0.57% to 0.06%) and placebo, −0.23% (95% confidence interval, −0.54% to 0.07%; P=0.46). During week 1 (inpatient cohort only), compared with placebo, tenapanor treatment resulted in higher stool sodium content (mean [±SD]: tenapanor, 36.6 [±21.8] mmol/d; placebo, 2.8 [±2.7] mmol/d; P<0.001) and higher stool weight (tenapanor, 172.5 [±68.1] g/d; placebo, 86.3 [±30.0] g/d; P<0.01). A similar safety profile was observed across treatment groups with the exception of diarrhea, which occurred more frequently with tenapanor treatment.

Conclusions

Tenapanor treatment increased stool sodium and weight over placebo in patients undergoing hemodialysis. However, over 4 weeks of treatment, there was no difference in interdialytic weight gain between patients treated with tenapanor and those receiving placebo.

Keywords: tenapanor; sodium/hydrogen antiporter; end-stage renal disease; chronic kidney disease stage 5D; Body Weight; Humans; Renal Dialysis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Sodium; Sodium-Hydrogen Antiporter; Weight Gain

Introduction

Patients with CKD stage 5D generally have minimal to no urine production, leading to fluid retention between dialysis sessions. This retention is quantified as interdialytic weight gain (IDWG). High IDWG is associated with hypertension (1), intradialytic hypotension (2), and adverse cardiovascular outcomes (3,4), including increased all–cause mortality (5). It is well accepted that the degree of IDWG is influenced by dietary sodium intake (6,7), and for this reason, guidelines suggest that individuals with CKD restrict dietary sodium intake (8,9). Studies of patients with CKD stage 5D suggest that restricting dietary sodium can improve left ventricular hypertrophy and reduce intradialytic hypotension (6,10). Although a reduction in dietary intake of sodium is recommended as an important intervention for patients with CKD, the ubiquitous addition of table salt to processed foods in conjunction with many patients being at a socioeconomic disadvantage means that it is difficult for patients to maintain an effective reduction in dietary sodium intake. Therefore, a therapeutic intervention that can reduce sodium absorption could be of potential benefit to these patients.

In the gastrointestinal tract, the sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) plays an important role in sodium and fluid homeostasis (11–13). Tenapanor (AZD1722 and RDX5791) is a small molecule inhibitor of NHE3 being developed for the treatment of patients with CKD. Tenapanor acts locally in the gut, and it has minimal systemic availability. In healthy volunteers, tenapanor treatment over 7 days reduced sodium absorption, resulting in increases in stool sodium of up to 50 mmol/d (corresponding to about 2.9 g table salt per day) with concomitant reductions in urinary sodium of a similar magnitude (14). Tenapanor may, therefore, have a role as a potential treatment for sodium and fluid overload in patients with CKD stage 5D. We evaluated these and other pharmacodynamic effects, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of tenapanor in patients with CKD stage 5D treated with hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a phase 2, randomized, double–blind, placebo–controlled, parallel design, multicenter study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier no. NCT01764854) conducted at 14 sites in the United States between January 29, 2013 and September 20, 2013. All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (Puyallup, WA) and the Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (Durham, NC). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

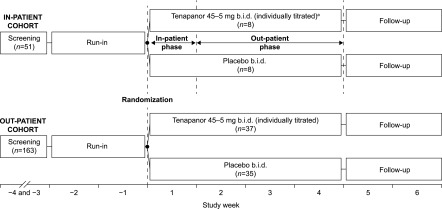

The study was initially designed to include a 1-week inpatient treatment phase for all participants followed by a 3-week outpatient treatment phase (Figure 1, inpatient cohort). After a protocol amendment after the first 16 individuals had been assigned to treatment, all subsequent patients were enrolled according to a modified study design with a 4-week outpatient treatment period only (outpatient cohort). These two cohorts were analyzed separately, and most data are presented for the larger outpatient cohort only.

Figure 1.

Study design. The inpatient cohort spent the first week in clinic for stool collection and the rest of treatment period under outpatient conditions. The outpatient cohort had no stool collection, and all 4 weeks were under outpatient conditions. aStarting dose reduced from 60 to 45 mg twice a day (b.i.d.) after reports of diarrhea.

Participants

Eligible participants had CKD stage 5D, were ages 18–80 years old, had body mass index 18–50 kg/m2, and were on stable three times weekly hemodialysis for at least 2 months. Patients were also required to have had a mean postdialysis weight variability of ≤2.0% during the 2-week run-in period before randomization, a mean IDWG of at least 3.0% of the postdialysis weight and at least 2 kg during the run-in period, a stable dialysate sodium and bicarbonate prescription during the 4 weeks before screening, and bowel movements at least twice weekly during the run-in period. If on antihypertensive agents, patients must have been on stable doses for at least 2 weeks before randomization.

Key exclusion criteria were urine production of ≥200 ml/d; predialysis systolic BP (SBP) >200 mmHg or diastolic BP >110 mmHg; predialysis SBP<110 mmHg; predialysis serum bicarbonate levels <18 mmol/L before randomization; signs of hypovolemia, inflammatory bowel disease, or other gastrointestinal diseases; and diarrhea or loose stools during the week before randomization (defined as the Bristol Stool Form Scale [BSFS] score ≥6 [15] and a daily stool frequency of three or more for ≥2 days).

Study Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned using a computer-generated schedule to receive either tenapanor hydrochloride capsules or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Patients were instructed to take the study drug twice daily immediately before morning and evening meals on days 1–28. If the dialysis session was scheduled early in the morning, patients were instructed to take the study drug after the dialysis session. The starting dose was 60 mg twice daily; however, owing to initial reports of diarrhea, the protocol was subsequently amended so that the starting dose was reduced to 45 mg twice daily, with all participants in the outpatient cohort receiving this starting dose. On the basis of tolerability and patient request, twice daily doses could be decreased stepwise as follows: 45 → 30 → 15 → 5 mg. Hemodialysis was performed three times weekly according to a stable schedule throughout the study.

Individuals in the inpatient cohort were admitted on the morning of the day before randomization and remained in the center for a total of 8 days. Inpatients received a diet with a sodium content on the basis of the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines (9) (per day, approximately 2.0 g sodium, 87 mmol, 5.1 g table salt) while in the study center. All patients were advised to maintain a similar low–sodium diet in the outpatient setting.

Study End Points and Methods of Assessment

The primary end point was change in mean relative IDWG from baseline to week 4. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg before and after each dialysis session. The same weighing scale was used for each patient at all visits, and the patient was instructed to wear light clothing consistently. Other end points included absolute IDWG, pre– and postdialysis mean sitting SBP and diastolic BP, interdialytic BP (self-monitoring at home before breakfast, lunch, and dinner on days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 42) and bioimpedance (total body and extra- and intracellular water; Quantum IV Bioimpedance Machine, RJL Systems, Clinton Township, MI), and 24-hour stool sodium and stool weight (inpatient cohort only; days 1–8 [days when stool measurements available]). Patient-reported assessments included daily reporting of stool consistency (according to the BSFS) (15), the 6-minute walk test, postdialysis recovery time, perceived thirst, and the patient–reported outcome instruments Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI), Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (SBQ), and Global Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Tablet compliance was calculated as the percentage of dispensed capsules tablets that was taken.

During the first week of treatment, blood samples for measurement of plasma tenapanor concentrations were collected predose on day 1 (both cohorts); postdose on days 1 and 7 after 1, 2, and 4 hours (inpatient cohort) or days 1 and 8 after 1 and 2 hours (outpatient cohort); and predialysis on days 3, 5, and 29 (the day after the last day of treatment; both cohorts).

Stool sodium was determined by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (RTI International). Plasma levels of tenapanor were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (MicroConstants Inc., San Diego, CA).

Statistical Analyses

The primary end point was analyzed as the change in mean relative IDWG from baseline to week 4. Baseline IDWG was determined by calculating the mean of the weight gains measured over six consecutive interdialytic intervals over the 2-week run-in period, with each interval starting immediately after a dialysis session (postdialysis weight) and ending before the next dialysis session (predialysis weight); each week consisted of two 2-day intervals and one 3-day interval. Week 4 IDWG was similarly determined by calculating the mean of the weight gains measured over three consecutive intervals during that week. The change in IDWG from baseline to week 4 was expressed as a percentage of the mean of the postdialysis weights over the 2-week run-in period. If any pre– or postdialysis weight values were missing in either week during run in, the week with nonmissing weight values was used for the baseline IDWG calculation. If there were missing values in both weeks during run in, consecutive interdialytic intervals with nonmissing values were used to construct a complete week of two 2-day interdialytic intervals and one 3-day interdialytic interval. For patients without complete data for week 4 (two 2-day IDWG measurements and one 3-day IDWG measurement), the data from week 3 were used; if week 3 data were also incomplete, the patient was excluded from the primary analysis.

Comparison of tenapanor with placebo treatment was performed using an analysis of covariance model with treatment group as a factor and baseline relative IDWG included as a covariate. A sample size of 35 patients per treatment group was calculated to yield 86% power, assuming a true treatment effect of 0.6% and an SD of 0.9% for change in relative IDWG (primary end point) using a one–sided significance level of 0.05. As a sensitivity analysis, a mixed model repeated measures analysis of change in IDWG was performed using an unstructured analysis of covariance model with fixed factors for treatment, study week, treatment by study week interaction, and adjustments for baseline IDWG, with testing at the two–sided significance level of 0.05. Post hoc analyses of differences between treatment groups were conducted for stool sodium and stool weight during week 1 (inpatient cohort only) using a t test at a two–sided significance level of 0.05. All other end points are presented with descriptive statistics without statistical inference testing.

Results

Study Participants

Figure 1 shows patient allocation for the inpatient and outpatient cohorts. Across both the inpatient and outpatient cohorts, the main reasons for screen failures were IDWG measurements <3% of postdialysis body weight during run in (57%), urine output of >200 ml/d during screening or run in (9%), and unstable dry weight during run in (>2% variation in postdialysis weights; 5%).

Baseline demographic and medical characteristics of all patients enrolled in the study are shown in Table 1. Baseline characteristics were generally similar in the two treatment groups for both cohorts. In the inpatient cohort, all 16 patients completed the study. For the outpatient cohort, 64 (89%) patients overall completed the study (tenapanor, 31; placebo, 33). Reasons for discontinuation in the tenapanor group were withdrawal of consent (one patient; 3%), adverse event (one patient; 3%), relocation (two patients; 6%), protocol violation (one patient; 3%), and unknown (one patient; 3%). In the placebo group, two patients (6%) withdrew from the study, both owing to a protocol violation.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Inpatient Cohort | Outpatient Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenapanor, n=8 | Placebo, n=8 | Tenapanor, n=37 | Placebo, n=35 | |

| Men, n (%) | 6 (75.0) | 5 (62.5) | 24 (64.9) | 20 (57.1) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 3 (8.1) | 0 |

| Black | 6 (75.0) | 6 (75.0) | 14 (37.8) | 19 (54.3) |

| White | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 18 (48.6) | 16 (45.7) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 13 (35.1) | 10 (28.6) |

| Age, yr | 47.9±8.3 | 54.4±6.5 | 51.5±11.5 | 49.3±11.8 |

| Range | 38–64 | 47–65 | 24–75 | 25–72 |

| Cause of CKD stage 5D, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 11 (29.7) | 11 (31.4) |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 14 (37.8) | 12 (34.3) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) |

| GN, primary and secondary | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) |

| Other | 2 (25.0) | 5 (62.5) | 5 (13.5) | 8 (22.9) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Time on dialysis, yr, median | 9.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Interquartile range | 6.0–19.5 | 2.5–9.5 | 3.0–9.0 | 3.0–9.0 |

| Baseline dialysis parameters | ||||

| Ultrafiltration rate, ml/h per kga | 12.0±5.0 | 7.1±6.7 | 12.6±4.3 | 12.3±3.0 |

| Dialysis session length, mina | 240±19 | 237±29 | 235±24b | 236±27c |

| Dialysis sodium concentration difference,d mmol/L | −4.8±5.0e | −3.0±6.5f | −4.8±5.5g | −4.8±5.4h |

| Predialysis weight, kga | 88.3±26.1 | 98.1±39.1 | 84.6±21.3 | 91.8±27.6 |

| Postdialysis weight, kga | 84.8±25.7 | 94.0±38.0 | 81.2±20.7 | 88.3±26.7 |

| IDWG, kgi | 3.5±0.6 | 4.1±1.1 | 3.4±1.1 | 3.7±1.1 |

Unless otherwise noted, values are mean±SD. IDWG, interdialytic weight gain.

Mean over up to six dialysis sessions during the 2-week run-in period.

n=36.

n=34.

(Predialysis serum sodium concentration [mean over up to six sessions]) − (dialysate sodium concentration).

n=6.

n=7.

n=34.

n=33.

Mean over up to six interdialytic intervals during the 2-week run-in period.

The mean dose of tenapanor was 32 mg twice daily in the outpatient cohort; 18 of 37 patients had a dose reduction from the starting dose because of gastrointestinal side effects (11 patients reduced to 30 mg, five patients reduced to 15 mg, and two patients reduced to 5 mg; all twice daily). The median length of treatment with study drug was 28 days in both treatment groups. Mean tablet compliance was higher in the placebo group (92%) than in the tenapanor group (83%).

IDWG

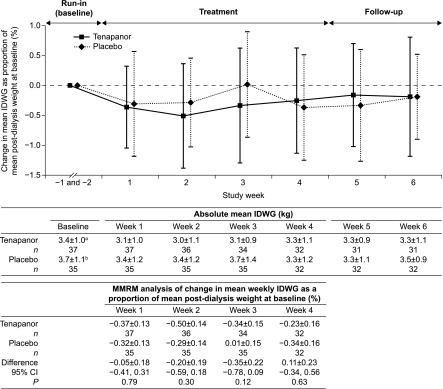

For the inpatient cohort, IDWG was relatively unchanged throughout the treatment and follow-up periods with both tenapanor and placebo treatment (Supplemental Material 1). All patients receiving placebo in the outpatient cohort were included in the analysis of the primary end point; for those patients receiving tenapanor, three had missing values at weeks 3 and 4 because of discontinuation in week 1 or 2 and were, thus, excluded from the primary analysis. At week 4, least squares mean changes in IDWG as a percentage of the mean postdialysis weight at baseline were −0.26% (95% confidence interval, −0.57% to 0.06%) and −0.23% (95% confidence interval, −0.54% to 0.07%) for the tenapanor and placebo groups, respectively (P=0.46 [one sided]; primary end point). Mean weekly absolute IDWG was similar in both treatment groups in the outpatient cohort as were the changes from baseline as percentages of mean postdialysis weight at baseline, with the mixed model repeated measures analysis showing no statistical differences between the groups during weeks 1–4 (Figure 2). Similar proportions of patients in both treatment groups achieved reductions in IDWG of at least 0.25 kg (tenapanor, 51%; placebo, 43%), 0.5 kg (tenapanor, 32%; placebo, 29%), and 0.75 kg (tenapanor, 22%; placebo, 26%) (Supplemental Material 2).

Figure 2.

Interdialytic weight gain (IDWG; primary end point) across the study period for the outpatient cohort. The least squares mean difference between tenapanor and placebo in the change in IDWG from baseline to week 4 as a proportion of mean baseline postdialysis weight is not significant (primary analysis; P=0.46 [one sided]). Values in the line graph are means±SD (offset for clarity). Absolute mean weekly IDWG is shown as mean±SD. Values in the mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis are shown as least squares means±SEM, with fixed factors for treatment, study week, and treatment by study week interaction and adjustments for baseline IDWG and testing at the two–sided 0.05 significance level. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. aMean postdialysis weight was 81.2±20.7 kg. bMean postdialysis weight was 88.3±26.7 kg.

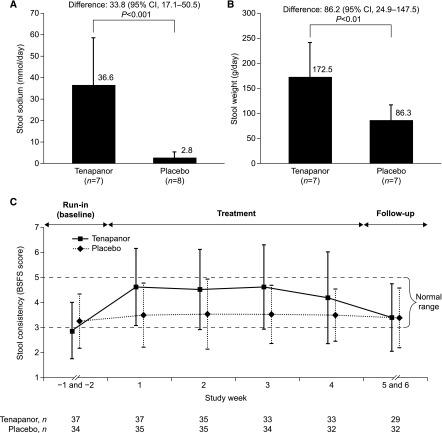

Other End Points

In the inpatient cohort stool collection period (week 1), tenapanor treatment resulted in higher stool sodium content over placebo (mean [±SD] over 7 days: tenapanor, 36.6 [±21.8] mmol/d; placebo, 2.8 [±2.7] mmol/d; P<0.001) (Figure 3A) and higher stool weight (tenapanor, 172.5 [±68.1] g/d; placebo, 86.3 [±30.0] g/d; P<0.01) (Figure 3B). Patients administered tenapanor had softer stools than those given placebo as measured by the BSFS (shown for the outpatient cohort in Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Effect of tenapanor to increase stool sodium, stool weight and stool consistency. Mean daily (A) stool sodium content and (B) stool weight during week 1 of treatment with tenapanor or placebo (inpatient cohort). (C) Patient–reported stool consistency according to the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) score over study duration (outpatient cohort). Values are means with one error bar showing 1 SD; statistical analyses were on the basis of post hoc t tests at a two–sided significance level of 0.05 in A and B. Values are means±SD (offset for clarity) in C. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

As expected for patients on hemodialysis, there was large variability in predialysis BP, with no apparent effects of tenapanor on predialysis BP (Table 2), interdialytic (home) BP, or total body and extracellular water as measured by bioimpedance (Table 2). There were no apparent differences between treatment groups in the 6-minute walk distance, postdialysis recovery time, perceived thirst, and patient-reported outcomes according to the DSI, SBQ and GHQ instruments (data not shown).

Table 2.

BP, body water, and serum electrolyte levels

| Characteristic | Inpatient Cohort: Baselinea | Outpatient Cohort: Tenapanor | Outpatient Cohort: Placebo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenapanor, n=8 | Placebo, n=8 | Baseline,a n=37 | Change from Baseline to End of Treatment,b n=35 | Baseline,a n=35 | Change from Baseline to End of Treatment,b n=34 | |

| Predialysis SBP, mmHg | 156.0±17.1 | 145.1±23.9 | 142.9±25.6 | −1.1±24.6c | 148.4±22.7 | −1.3±22.9 |

| Predialysis DBP, mmHg | 86.5±7.9 | 77.3±16.1 | 76.8±13.8 | −1.6±10.7c | 81.6±16.2 | −0.1±11.2 |

| Total body water, L | 48.0±14.7 | 50.1±16.8 | 47.4±10.5d | 0.3±5.6e | 46.9±13.8c | 1.9±5.8f |

| Extracellular water, L | 22.3±8.1 | 22.7±6.8 | 22.4±4.8d | 0.0±2.9e | 21.7±6.2c | 0.7±3.2f |

| Calcium, mg/dlg | 8.9±0.6 | 9.3±0.7 | 8.9±0.6 | 0.2±0.7 | 8.7±0.6 | 0.0±0.7 |

| Potassium, mEq/Lg | 4.8±0.5 | 4.9±0.5 | 5.0±0.6 | −0.1±0.8 | 5.4±1.0 | −0.2±0.6 |

| Sodium, mEq/Lg | 136.0±3.1 | 136.4±3.0 | 135.0±3.7 | −0.8±3.6 | 135.5±2.5 | 0.3±2.7 |

| Phosphate, mg/dlg | 6.1±1.8 | 5.4±1.3 | 5.2±1.8 | −0.8±1.5 | 6.3±1.9 | −0.4±1.6 |

| Carbon dioxide, mEq/Lg | 24.1±5.3 | 24.5±5.2 | 20.4±3.0 | −0.8±2.7 | 19.3±2.8 | 1.1±3.3 |

Values are means±SD. SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP.

Taken on day 1.

Taken on day 29.

n=34.

n=36.

n=33.

n=31.

Taken before dialysis.

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma tenapanor levels were below the limit of quantification (0.5 ng/ml) in all but three of the 390 (>99%) samples taken from individuals receiving tenapanor. These three samples were from two patients who received tenapanor at a dose of 45 mg twice daily, with tenapanor plasma concentrations ranging from 0.54 to 0.96 ng/ml.

Safety and Tolerability

A summary of adverse events for the outpatient cohort is shown in Table 3. A similar safety profile was observed across treatment groups with the exception of diarrhea, which occurred more frequently in the tenapanor group. All events of diarrhea were mild or moderate in severity, except for those in four patients receiving tenapanor who experienced severe diarrhea. Serious adverse events were reported by three patients in the outpatient cohort. These consisted of pneumonia (placebo), urinary tract infection (tenapanor), and syncope in combination with humerus fracture (tenapanor), with the latter resulting in treatment discontinuation. All serious adverse events were judged as unrelated to treatment and resolved after follow-up. No clinically relevant laboratory or physical examination findings, vital signs, or electrocardiogram abnormalities were seen in tenapanor-treated patients. Serum electrolyte levels were largely unchanged from baseline after treatment with tenapanor or placebo (Table 2). The safety profile for the inpatient cohort was similar to that of the outpatient cohort. Three patients, all in the placebo group, experienced a total of four serious adverse events; these comprised local neck swelling, syncope, anemia, and acute respiratory failure.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events (outpatient cohort)

| Adverse Event Category | Tenapanor, n=37 | Placebo, n=35 |

|---|---|---|

| At least one adverse event | 33 (89.2) | 25 (71.4) |

| Treatment–related adverse eventa | 17 (45.9) | 4 (11.4) |

| Serious adverse eventb | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) |

| Adverse event leading to discontinuation | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Adverse event by system organ class (preferred term)c | ||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 23 (62.2) | 7 (20.0) |

| Diarrhea | 21 (56.8) | 3 (8.6) |

| Nausea | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Vomiting | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Investigations | 7 (18.9) | 6 (17.1) |

| Blood carbon dioxide decreased | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) |

| Blood parathyroid hormone increased | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.7) |

| Blood potassium increased | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Blood sodium decreased | 2 (5.4) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 6 (16.2) | 7 (20.0) |

| Muscle spasms | 6 (16.2) | 5 (14.3) |

| Vascular disorders | 6 (16.2) | 6 (17.1) |

| Hypotension | 5 (13.5) | 6 (17.1) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 6 (16.2) | 4 (11.4) |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 (8.1) | 0 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) |

| Metabolic acidosis | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Hypocalcemia | 0 | 2 (5.7) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 5 (13.5) | 5 (14.3) |

| Procedural hypotension | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 5 (13.5) | 4 (11.4) |

| Chest pain | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) |

| Catheter site pain | 2 (5.4) | 0 |

| Malaise | 1 (2.7) | 3 (8.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 5 (13.5) | 3 (8.6) |

| Dizziness | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.7) |

| Headache | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) |

| Dyspnea | 2 (5.4) | 0 |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) |

| Cardiac failure congestive | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

Values are n (%).

As judged by the investigator.

Pneumonia (placebo: n=1), urinary tract infection (tenapanor: n=1), and syncope in combination with humerus fracture (tenapanor: n=1).

Any adverse event reported by at least two participants.

Discussion

This proof of concept study evaluated whether tenapanor, a minimally systemically available inhibitor of NHE3 that reduces absorption of dietary sodium, could reduce IDWG in patients with CKD stage 5D treated with hemodialysis. It was anticipated that, through a reduction of intestinal sodium absorption, tenapanor treatment would lead to reductions in fluid uptake and IDWG. Consistent with findings in healthy volunteers (14), stool collection during the 1-week inpatient component of our study showed that tenapanor treatment increased stool sodium in patients with CKD stage 5D as shown by an increase over placebo in mean stool sodium of 33.8 mmol/d (Figure 3A). This is representative of a reduction of sodium absorption equivalent to that contained in about 2 g table salt per day. Increased stool sodium was accompanied by an increase in mean stool weight, which is representative of increased fluid excretion via the gut (Figure 3B). However, despite achieving the expected pharmacodynamic effects with regard to both stool sodium and weight, we were unable to detect a difference between patients treated with tenapanor or placebo in the primary end point of change in mean relative IDWG over 4 weeks of treatment (Figure 2).

There are several possible reasons why tenapanor treatment did not result in detectable IDWG reductions from baseline relative to placebo. Despite the long duration on dialysis of the patients in the trial, it is possible that reductions in sodium and subsequently, fluid uptake provided by tenapanor were partially compensated for by reductions in urine volume. The volume of fluid diverted to stool may have been associated with the high rates of diarrhea observed in the tenapanor group, which may be expected to result in increased thirst. Being largely an outpatient study, food and fluid intake could not be controlled; however, our thirst questionnaire did not provide evidence of increased thirst. Factors associated with the dialysis setting, such as dialysate sodium concentrations, may also have influenced results. Dialysate sodium concentrations used during the study were typically around 5 mmol/L higher than predialysis serum sodium concentrations (Table 1). This practice can lead to postdialysis hypernatremia that contributes to volume overload and increased BP (16). An increase of 0.17% of body weight for each additional 2 mmol/L dialysate sodium concentration has been reported (17). Reducing or individualizing dialysate sodium is now recommended as a means of improving control of sodium balance, volume, and BP in hypertensive patients on hemodialysis (16,18), and it has been shown to reduce IDWG and BP (19). Emerging data from investigations of patients on hemodialysis using magnetic resonance imaging suggest that osmotically inactive sodium is stored in body tissues (20). The potential mobilization of tissue sodium or the effects on whole–body sodium balance caused by reduced uptake of sodium from the gut during tenapanor treatment were not investigated as part of our study. Therefore, reductions in fluid overload after tenapanor treatment may have been mitigated by these potentially confounding factors related to sodium and fluid balance. Collectively, these factors highlight the difficulties associated with using IDWG as a clinical end point.

Although this study was not designed to evaluate BP effects, there were no major changes in predialysis BP (Table 2) or interdialytic BP after tenapanor treatment. A recent review (21) discusses the difficulties of measuring BP in patients on dialysis, especially when using pre- and postdialysis measurements. Notwithstanding these considerations, the absence of any major effects on BP after tenapanor treatment in our study is in line with the lack of effect on IDWG.

Consistent with results in healthy volunteers (14), the pharmacokinetic measurements in this study confirmed that tenapanor had minimal systemic exposure in patients with CKD stage 5D. The most common adverse event with tenapanor was diarrhea, which was expected from the pharmacodynamic effect on stool sodium. Starting doses of tenapanor were reduced according to gastrointestinal tolerability: it is not known whether maintenance of higher doses throughout the study would have resulted in effects on IDWG. Additional evaluation of the safety profile of tenapanor is required.

In conclusion, this placebo-controlled study in patients with CKD stage 5D undergoing hemodialysis showed that tenapanor treatment increased stool sodium and increased stool weight. However, the study failed to meet the primary end point of a reduction in relative IDWG for reasons that are unknown. The clinical benefits of increasing intestinal sodium excretion via inhibition of NHE3 require additional investigation.

Disclosures

G.A.B. is an adviser for Ardelyx Inc. (Fremont, CA), and he and his practice have received equity ownership interest in Ardelyx Inc. D.P.R. is an employee of and has ownership interests in Ardelyx Inc. M.L.-Z., B.V.S., and M.K. are employees of AstraZeneca R&D (Mölndal, Sweden). T.R.-B., P.J.G., S.A.J., and B.C.C. are employees of and have ownership interests in AstraZeneca R&D.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, the study centers, and the clinical teams.

This study was funded by AstraZeneca R&D (Mölndal, Sweden). Medical writing support was provided by Richard Claes and Steven Inglis from Oxford PharmaGenesis (Oxford, United Kingdom) and funded by AstraZeneca R&D.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.09050815/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Inrig JK, Patel UD, Gillespie BS, Hasselblad V, Himmelfarb J, Reddan D, Lindsay RM, Winchester JF, Stivelman J, Toto R, Szczech LA: Relationship between interdialytic weight gain and blood pressure among prevalent hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 108–118, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefánsson BV, Brunelli SM, Cabrera C, Rosenbaum D, Anum E, Ramakrishnan K, Jensen DE, Stålhammar NO: Intradialytic hypotension and risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2124–2132, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmberg B, Stegmayr BG: Cardiovascular conditions in hemodialysis patients may be worsened by extensive interdialytic weight gain. Hemodial Int 13: 27–31, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MJ, Doh FM, Kim CH, Koo HM, Oh HJ, Park JT, Han SH, Yoo TH, Kim YL, Kim YS, Yang CW, Kim NH, Kang SW: Interdialytic weight gain and cardiovascular outcome in incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 39: 427–435, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Van Wyck D, Bunnapradist S, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC: Fluid retention is associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis. Circulation 119: 671–679, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayikcioglu M, Tumuklu M, Ozkahya M, Ozdogan O, Asci G, Duman S, Toz H, Can LH, Basci A, Ok E: The benefit of salt restriction in the treatment of end-stage renal disease by haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 956–962, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maduell F, Navarro V: Dietary salt intake and blood pressure control in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 2063, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anonymous: Chapter 3: Management of progression and complications of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 3: 73–90, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.K/DOQI Workgroup : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 45[Suppl 3]: S1–S153, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozkahya M, Toz H, Qzerkan F, Duman S, Ok E, Basci A, Mees EJ: Impact of volume control on left ventricular hypertrophy in dialysis patients. J Nephrol 15: 655–660, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broere N, Chen M, Cinar A, Singh AK, Hillesheim J, Riederer B, Lünnemann M, Rottinghaus I, Krabbenhöft A, Engelhardt R, Rausch B, Weinman EJ, Donowitz M, Hubbard A, Kocher O, de Jonge HR, Hogema BM, Seidler U: Defective jejunal and colonic salt absorption and alteredNa(+)/H (+) exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity in NHE regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) adaptor protein-deficient mice. Pflugers Arch 457: 1079–1091, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlowski J, Kandasamy RA, Shull GE: Molecular cloning of putative members of the Na/H exchanger gene family. cDNA cloning, deduced amino acid sequence, and mRNA tissue expression of the rat Na/H exchanger NHE-1 and two structurally related proteins. J Biol Chem 267: 9331–9339, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tse CM, Brant SR, Walker MS, Pouyssegur J, Donowitz M: Cloning and sequencing of a rabbit cDNA encoding an intestinal and kidney-specific Na+/H+ exchanger isoform (NHE-3). J Biol Chem 267: 9340–9346, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer AG, Labonte ED, Rosenbaum DP, Plato CF, Carreras CW, Leadbetter MR, Kozuka K, Kohler J, Koo-McCoy S, He L, Bell N, Tabora J, Joly KM, Navre M, Jacobs JW, Charmot D: Intestinal inhibition of the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 prevents cardiorenal damage in rats and inhibits Na+ uptake in humans. Sci Transl Med 6: 227ra36, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW: Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 32: 920–924, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos SF, Peixoto AJ: Revisiting the dialysate sodium prescription as a tool for better blood pressure and interdialytic weight gain management in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 522–530, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecking M, Karaboyas A, Saran R, Sen A, Inaba M, Rayner H, Hörl WH, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Sunder-Plassmann G, Port FK: Dialysate sodium concentration and the association with interdialytic weight gain, hospitalization, and mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 92–100, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner DE, Brunelli SM, Hunt A, Schiller B, Glassock R, Maddux FW, Johnson D, Parker T, Nissenson A: Improving clinical outcomes among hemodialysis patients: A proposal for a “volume first” approach from the chief medical officers of US dialysis providers. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 685–695, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz Mendoza J, Bayes LY, Sun S, Doss S, Schiller B: Effect of lowering dialysate sodium concentration on interdialytic weight gain and blood pressure in patients undergoing thrice-weekly in-center nocturnal hemodialysis: A quality improvement study. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 956–963, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahlmann A, Dörfelt K, Eicher F, Linz P, Kopp C, Mössinger I, Horn S, Büschges-Seraphin B, Wabel P, Hammon M, Cavallaro A, Eckardt KU, Kotanko P, Levin NW, Johannes B, Uder M, Luft FC, Müller DN, Titze JM: Magnetic resonance-determined sodium removal from tissue stores in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 87: 434–441, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal R, Flynn J, Pogue V, Rahman M, Reisin E, Weir MR: Assessment and management of hypertension in patients on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1630–1646, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.