Abstract

Background and objectives

Older patients reaching ESRD have a higher risk of adverse health outcomes. We aimed to determine the association of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse health outcomes in patients reaching ESRD. Understanding these associations could ultimately lead to prediction models to guide tailored treatment decisions or preventive interventions.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, CENTRAL, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and COCHRANE for original studies published until February 8, 2016 reporting on the association of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty with adverse health outcome after follow-up in patients reaching ESRD either with or without RRT.

Results

Of 7451 identified citations, we included 30 articles that reported on 35 associations. Mean age was >60 years old in 73% of the studies, and geriatric conditions were highly prevalent. Twenty-four studies (80%) reported on functional impairment, seven (23%) reported on cognitive impairment, and four (13%) reported on frailty. Mortality was the main outcome measure in 29 studies (97%), and one study assessed functional status trajectory. In 34 of 35 (97%) associations reported, functional or cognitive impairment or frailty was significantly and independently associated with adverse health outcomes. The majority of studies (83%) were conducted in selected patient populations, mainly patients on incident dialysis.

Conclusions

Functional and cognitive impairment and frailty in patients reaching ESRD are highly prevalent and strongly and independently associated with adverse health outcomes, and they may, therefore, be useful for risk stratification. More research into their prognostic value is needed.

Keywords: end stage renal disease; dialysis; functional impairment; cognitive impairment; frail elderly; Cognition Disorders; Follow-Up Studies; Humans; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Outcome Assessment (Health Care); renal dialysis; Renal Replacement Therapy

Introduction

The number of older patients with ESRD is increasing rapidly worldwide (1,2). In the United States, patients >65 years of age now represent 38% of the ESRD population (1). When patients reach ESRD, different treatment options emerge: RRT (dialysis or kidney transplantation) or conservative kidney management (CKM). Older patients with ESRD are known to have a higher risk of adverse health outcomes after RRT initiation, including mortality, cognitive and functional decline, and loss of quality of life (QOL) (3–6). The risk of poor outcome, however, differs greatly in older patients with ESRD because of substantial heterogeneity with respect to the presence of comorbidities and geriatric conditions, such as functional and cognitive impairment and frailty (7,8). Establishing which of these conditions independently associates with poor outcome may ultimately help to better identify those patients at highest risk and thus, guide informed treatment decisions or preventive interventions.

In the past years throughout different fields of medicine, there is growing evidence for the usefulness of measuring functional and cognitive impairment and frailty to risk stratify older individuals and guide treatment decision making (9–11). However, it is also unknown whether, in patients with ESRD, functional and cognitive impairment and frailty associate with poor outcome. Burden of comorbidities (12–14), peripheral vascular disease (15), and laboratory values, such as albumin (16,17), are known risk factors for poor outcome in patients reaching ESRD. Some of these risk factors are also associated with a higher risk of functional or cognitive decline or frailty; therefore, it is unknown whether a potential association between functional or cognitive impairment or frailty and adverse health outcomes is independent of these risk factors.

In this systematic review, we, therefore, aimed to determine the association of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse health outcomes in patients reaching ESRD, independent of known risk factors.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We set out to identify longitudinal studies in patients reaching ESRD in which the association between a measurement of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty before or at treatment initiation and adverse health outcome after follow-up was examined. The decision for a specific treatment modality, including RRT or CKM, is made if the renal function of a patient reaches end stage. We, therefore, chose to search for studies of patients with eGFR<20 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and before or within 60 days after initiation of RRT (hereafter referred to as patients reaching ESRD). As baseline measurement, we assessed the presence of functional impairment (including assessment of functional performance, mobility, and objectively measured physical performance; e.g., gait speed or grip strength), cognitive impairment (including assessment of cognition, dementia diagnosis, and a clinical diagnosis of depression), and frailty. We determined adverse health outcomes of mortality, hospitalization, functional or cognitive decline, and reduced QOL occurring after initiation of RRT or CKM. We did not apply an age or follow-up cutoff.

The search strategy was implemented on February 8, 2016 and restricted to human studies in the English language, and it used synonyms of the different domains of geriatric assessments combined with synonyms of the selected ESRD study population (a full Medline search is in Supplemental Material). A tailored search was extended to the following electronic databases: Embase, Web of Science, CENTRAL, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and COCHRANE.

Article Selection

The eligibility of all studies identified by the search was independently evaluated by two reviewers (M.H.K. and H.A.K.). For any article that seemed potentially relevant on the basis of title and abstract, full text was retrieved and screened. The reference list of the included publications was used for final crossreferencing. Studies were included if the full text contained original data on the association of any measurement of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty in patients reaching ESRD with adverse outcomes after initiation of RRT or CKM. In case of disagreement between the two reviewers, consensus was reached after discussion with a third reviewer (S.P.M.).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Items extracted from each study included publication data, study design and setting, patient characteristics (sample size, mean age, and treatment modality), measurement of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty, outcome measure, and results of the association of geriatric impairments with outcome. To assess the methodologic quality and risk of bias of the included studies, we adapted the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (18) to the purpose of this review (Supplemental Material).

Data Presentation

Study characteristics are tabulated per individual study. Sample size aggregate of the included studies is expressed as median and interquartile range. Main findings of the studies with respect to the association of measurement of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty with outcome are tabulated. The reported hazard ratios (HRs), odds ratios (ORs), and relative risks are adjusted for age and sex in multivariate analysis unless otherwise specified. We assessed whether the reported estimate changed when using a fully adjusted model controlling for all possible confounders, including multiple known risk factors for poor outcome, such as comorbidity burden.

Results

Search Results and Study Selection

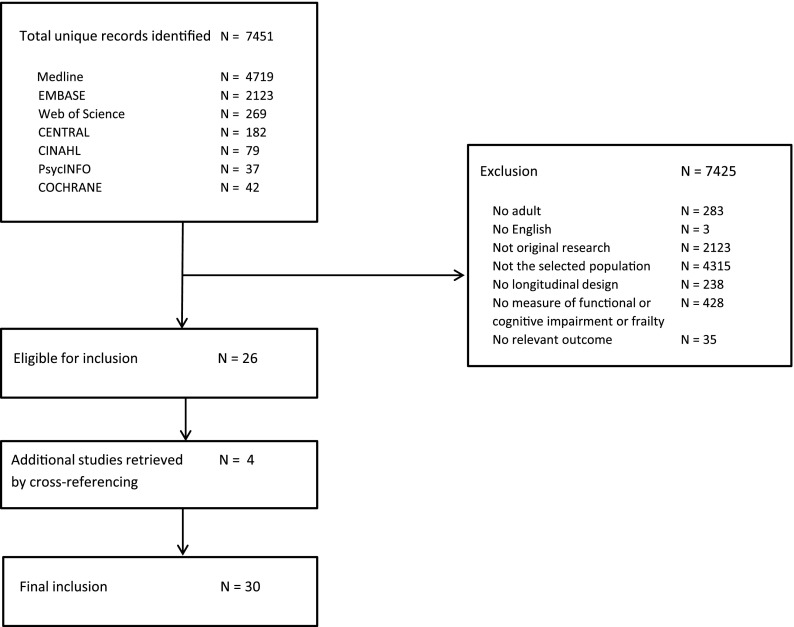

The database searches identified 7451 unique citations (Figure 1). After the initial screening by title and abstract, 309 articles were considered potentially eligible. After full-text review, another 283 were excluded; the remaining 26 articles were included. Crossreferencing yielded an additional four relevant articles, which adds up to a total of 30 studies that were included in this review.

Figure 1.

Search results and study selection.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 shows an overview of the study characteristics for the 30 included studies. The median sample size of all 30 studies was 1219 (interquartile range, 294–13,186), and the mean age was >60 years old in 22 studies (73%). Seventeen studies (57%) were published in the past 5 years, and 25 studies (83%) were conducted in Europe or the United States. Twenty-four studies (80%) selectively studied patients on incident dialysis, four (13%) studied patients reaching ESRD irrespective of treatment modality, which could consist of RRT or CKM, and one exclusively studied patients treated with CKM. Only one study included three patients who underwent preemptive kidney transplantation in addition to patients on dialysis, but it did not separately report on their outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Publication | Patients | Study Setting | Treatment Modality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Year | Country | No. of Patients | Mean Age, yr | ||

| Alfaadhel et al. (47) | 2015 | Canada | 390 | 63 | Patients on incident dialysis at a single center | HD, PD |

| Arai et al. (35) | 2014 | Japan | 202 | 80.4 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥75 yr old at a single center | HD, PD |

| Bao et al. (46) | 2012 | United States | 1576 | 59.6 | Patients on incident dialysis from the Comprehensive Dialysis Study of US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Bowling et al. (31) | 2015 | United States | 27,913 | 80.8 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥75 yr old; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Carlson et al. (23) | 1987 | United States | 979 | 52 | Patients on incident dialysis at 27 renal units | HD, PD |

| Chandna et al. (19) | 1999 | United Kingdom | 292 | 61.3 | Patients on incident dialysis at a single center | HD, PD |

| Couchoud et al. (36) | 2009 | France | 2500 | 80.9 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥75 yr old; data from the French REIN Registry | HD, PD |

| Couchoud et al. (37) | 2015 | France | 12,500 | 81.1a | Patients on incident dialysis ≥75 yr old; data from the French REIN Registry | HD, PD |

| Decourt et al. (38) | 2016 | France | 1459 | 72.3a | Patients on incident dialysis with ESRD caused by monoclonal gammopathies, data from the French REIN Registry | HD, PD |

| Doi et al. (29) | 2015 | Japan | 688 | 69a | Patients on incident dialysis at 21 renal units | HD |

| Dusseux et al. (34) | 2015 | France | 8955 | 78a | Patients on incident dialysis ≥70 yr old; data from the French REIN Registry | HD, PD |

| Glaudet et al. (33) | 2013 | France | 557 | 71.3 | Patients on incident dialysis; data from the French REIN Registry | HD, PD |

| Hussain et al. (28) | 2013 | United Kingdom | 441 | NA | Predialysis patients (eGFR<20 ml/min per 1.73 m2) ≥70 yr old at a single center | HD, PD, CKM |

| Isoyama et al. (41) | 2014 | Sweden | 330 | 53 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥75 yr old at a single center | HD, PD |

| Johansen et al. (45) | 2007 | United States | 2275 | 58.2 | Patients on incident dialysis from US Renal Data System Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study Wave 2 cohort | HD, PD |

| Joly et al. (21) | 2003 | France | 144 | 83.4 | Predialysis patients (eGFR<10 ml/min per 1.73 m2) ≥80 yr old at a single center | HD, CKM |

| Kurella et al. (32) | 2007 | United States | 83,996 | 84.2 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥80 yr old; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Kurella Tamura et al. (43) | 2009 | United States | 3702 | 73.4 | Nursing home residents initiating dialysis; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Krishnan et al. (39) | 2015 | United States | 45,357 | NA | Patients on incident dialysis ≥66 yr old; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Lopez Revuelta et al. (24) | 2004 | Spain | 318 | 60.2 | Patients on incident dialysis at 34 renal units | HD, PD |

| Mauri et al. (20) | 2008 | Spain | 3445 | 64.6 | Patients on incident dialysis; data from Renal Registry of Catalonia | HD |

| McClellan et al. (25) | 1991 | United States | 294 | 56.6 | Patients on incident dialysis at 37 renal units | HD, PD |

| Meulendijks et al. (48) | 2015 | The Netherlands | 65 | 75a | Predialysis patients (eGFR<20 ml/min per 1.73 m2) ≥65 yr old at a single center | HD, PD, CKM |

| Murtagh et al. (22) | 2011 | United Kingdom | 74 | 80.7 | Predialysis patients (eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) managed conservatively at three renal units | CKM |

| Park et al. (44) | 2015 | Korea | 24,738 | 57.9 | Patients on incident dialysis; data from the Korean Health Insurance database | HD |

| Rakowski et al. (40) | 2006 | United States | 272,024 | 62.6 | Patients on incident dialysis; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

| Shum et al. (27) | 2013 | China | 199 | 73.8 | Predialysis patients (eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) ≥65 yr old at a single center | PD, CKM |

| Soucie et al. (26) | 1996 | United States | 15,245 | 56.8 | Patients on incident dialysis; data from ESRD registry | HD, PD |

| Stenvinkel et al. (42) | 2002 | Sweden | 206 | 52 | Predialysis patients (eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) at a single center | HD, PD, KT |

| Thamer et al. (30) | 2015 | United States | 52,796 | 76.9 | Patients on incident dialysis ≥67 yr old; data from US Renal Data System | HD, PD |

HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; REIN, Renal Epidemiology and Information Network; NA, not available; CKM, conservative kidney management; KT, kidney transplantation.

Median.

Table 2 shows an overview of the association of measures of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse health outcomes after follow-up. The 30 studies reported on a total of 35 associations. Twenty-four studies (80%) reported on measurements of functional impairment. Seven studies (23%) examined the association of a clinical diagnosis of dementia or depression before dialysis initiation with outcome. None of the included studies addressed neuropsychologic measurements of cognition in patients reaching ESRD. Four studies reported on frailty (13%). Mortality was the main outcome measure of interest in 29 studies (97%); the remaining study assessed functional status trajectory during follow-up. In addition, hospitalization risk was addressed as a secondary outcome measure in five studies. No studies were found reporting on QOL or cognitive decline after initiation of RRT or CKM.

Table 2.

Association of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse health outcomes

| Authors | No. of Patients | Treatment Modality | Geriatric Assessment | Outcome | Associationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfaadhel et al. (47) | 390 | HD, PD | CFS | Mortality | Frailty at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk with each 1-point increase in CFS (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.52) |

| Arai et al. (35) | 202 | HD, PD | Mobility (ability or lack of ability to walk without assistance) | 6-mo Mortality | Impaired mobility at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 6-mo mortality risk (aHR, 4.94; 95% CI, 1.42 to 17.1) |

| Bao et al. (46) | 1576 | HD, PD | Modified version of Fried criteria for frailty | Mortality, time to first hospitalization | Frailty at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.25 to 1.97) and time to first hospitalization (aHR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.45) |

| Bowling et al. (31) | 27,913 | HD, PD | Functional impairment (inability to walk or transfer or requiring assistance with daily activities) | Mortality | Functional impairment at dialysis initiation was associated with a higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.31) |

| Carlson et al. (23) | 979 | HD, PD | KPS | Mortality | KPS scores at dialysis initiation in patients still alive after 2 yr of follow-up were higher compared with those in patients who died (KPS=65.6 versus 53.6, respectively; P<0.001) |

| Chandna et al. (19) | 292 | HD, PD | KPS | Mortality | Lower KPS at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97 to 0.99 per KPS point) |

| Couchoud et al. (36) | 2500 | HD, PD | Mobility (walk without help, assistance with or total dependency for transfers); severe behavioral disorders (including dementia) | 6-mo Mortality | Total dependency for transfers at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 6-mo mortality risk (aOR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.0) compared with assistance or no help needed; presence of severe behavioral disorders was associated with higher 6-mo mortality (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2 to 1.8) |

| Couchoud et al. (37) | 12,500 | HD, PD | Mobility (walk without help, assistance with or total dependency for transfers); severe behavioral disorders (including dementia) | 3-mo Mortality | Impaired mobility at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 3-mo mortality risk: requiring assistance for transfers aOR, 2.47; 95% CI, 2.10 to 2.91 and total dependency for transfers aOR, 6.53; 95% CI, 5.38 to 7.92 compared with no help needed; presence of severe behavioral disorders was associated with higher 3-mo mortality (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.85) |

| Decourt et al. (38) | 1459 | HD, PD | Mobility (inability to walk without help) | Mortality | Impaired mobility at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.58 to 2.36) |

| Doi et al. (29) | 688 | HD | WHO performance score | 1-yr Mortality | Higher WHO performance score at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 1-yr mortality risk: WHO scores 1 and 2 aOR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.45 to 9.13 and WHO scores 3 and 4 aOR, 6.75; 95% CI, 1.51 to 30.1 |

| Dusseux et al. (34) | 8955 | HD, PD | Mobility (walk without help, assistance with or total dependency for transfers); severe behavioral disorders (including dementia) | 3-yr Mortality | Impaired mobility at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 3-yr mortality risk: requiring assistance for transfers aOR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.47 to 1.90 and total dependency for transfers aOR, 2.99; 95% CI, 2.34 to 3.83 compared with no help needed; presence of severe behavioral disorders was associated with higher 3-yr mortality (aOR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.62 to 2.84) |

| Glaudet et al. (33) | 557 | HD, PD | Mobility (walk without help, assistance with or total dependency for transfers) | 4-yr Mortality | Impaired mobility at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 4-yr mortality risk in patients >75 yr old: requiring assistance for transfers aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.74 and total dependency for transfers aHR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.96 compared with no help needed |

| Hussain et al. (28) | 441 | HD, PD, CKM | WHO performance score | Mortality | Higher WHO performance score was associated with lower survival after both dialysis initiation and CKM (univariate analysis without reported estimate; P<0.001) |

| Isoyama et al. (41) | 330 | HD, PD | HGS | Mortality | Lower HGS (<20 kg in women, <30 kg in men) at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.94) |

| Johansen et al. (45) | 2275 | HD, PD | Modified version of Fried criteria for frailty | Mortality, hospitalization | Frailty at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.60 to 3.15) and combined outcome of death or hospitalization (aHR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.36 to 1.79 |

| Joly et al. (21) | 144 | HD, CKM | KPS; documented clinical diagnosis of dementia | Overall and 1-yr mortality | Functional dependency at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 1-yr mortality (aHR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.00 to 5.50) but not with >12-mo mortality (aHR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.42 to 2.36); presence of dementia was not significantly associated with mortality (no estimate reported) |

| Krishnan et al. (39) | 45,357 | HD, PD | Mobility (inability to ambulate from at least one claim for a wheelchair or wheelchair accessories) | 1-yr Mortality | Impaired mobility before dialysis initiation was associated with higher 1-yr mortality risk: impaired mobility from Medical Evidence Report aHR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.84 to 2.00 and claims aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.31 |

| Kurella et al. (32) | 83,996 | HD, PD | Nonambulatory status (inability to walk or transfer) | Mortality | Nonambulatory status at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk in octo- and nonagenarians (aRR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.49 to 1.58) |

| Kurella Tamura et al. (43) | 3702 | HD, PD | Documented clinical diagnosis of dementia | Functional status trajectory | Presence of dementia at dialysis initiation was associated with lower odds of maintained functional status 12 mo after start of dialysis (aOR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9) |

| Lopez Revuelta et al. (24) | 318 | HD, PD | Modified version of the KPS | Mortality, hospitalization days | Lower KPS score at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.44 to 1.97 per 10 points lower on KPS score) and no. of hospitalization days (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.48 per 10 points lower on KPS score) |

| Mauri et al. (20) | 3445 | HD | Modified version of the KPS | 1-yr Mortality | Functional dependency at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 1-yr mortality risk: requiring special care for daily living aOR, 3.83; 95% CI, 2.84 to 5.16 and having limited functional autonomy aOR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.45 to 2.43 compared with patients with normal functional independence |

| McClellan et al. (25) | 294 | HD, PD | KPS; clinical diagnosis of depression | Mortality | Lower KPS score at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality: cumulative 1-yr survival was 94.5% in the highest quartile and 55.7% in the lowest quartile of functional status (P<0.001); depression diagnosed before dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality: cumulative 1-yr survival was 58.3% versus 81.9% in patients without a history of depression (P=0.01) |

| Meulendijks et al. (48) | 65 | HD, PD, CKM | Groningen Frailty Indicator | 1-yr Mortality, hospitalization | 1-yr Mortality risk was higher in frail patients compared with nonfrail patients (30% versus 9%; P=0.04); hospitalization risk within 1 yr was higher in frail patients compared with nonfrail patients (90% versus 53%; P<0.01) |

| Murtagh et al. (22) | 74 | CKM | KPS | Mortality | Functional status at study entry was lower in patients on CKM who died during follow-up versus those still alive at study end (KPS score 60% versus 70%; P=0.01) |

| Park et al. (44) | 24,738 | HD | Documented diagnosis of dementia (on the basis of coding in Health Insurance database) | Mortality | Dementia diagnosed before dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.34 to 1.46) |

| Rakowski et al. (40) | 272,024 | HD, PD | Documented diagnosis of dementia (on the basis of coding in Medicare system); nonambulatory status (inability to walk or transfer) | Mortality | Dementia diagnosed before dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality (aHR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.77 to 1.98); nonambulatory status at dialysis initiation was associated with higher mortality risk: inability to walk aHR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.43 and inability to transfer aHR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.43 to 1.52 |

| Shum et al. (27) | 199 | PD, CKM | Basic Activities of Daily Living | Mortality, hospitalization, hospital days | Impairment in basic activities of daily living at PD initiation was associated with higher mortality risk (aHR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.28 to 3.46) as well as emergency hospitalization (β=0.20; P<0.01) and hospital days (β=0.22; P<0.01) after log transformation |

| Soucie et al. (26) | 15,245 | HD, PD | Modified version of the KPS; clinical diagnosis of depression | Mortality | Impaired functional status at dialysis initiation was associated with a higher risk of early mortality within 90 d (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9 to 2.3 for moderate impairment and aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.4 to 3.6 for severely impaired functional status); depression diagnosed before dialysis initiation was associated with a higher risk of early mortality within 90 d after dialysis initiation (aOR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.6) |

| Stenvinkel et al. (42) | 206 | HD, PD, KT | HGS | Mortality | Higher HGS at RRT initiation was significantly associated with lower mortality compared with those with HGS below the median (log rank =7.2; P<0.01) |

| Thamer et al. (30) | 52,796 | HD, PD | Assistance with daily living (requiring assistance with daily living, inability to ambulate, or has an amputation); documented diagnosis of dementia | 3-mo Mortality | Requiring assistance with daily living or walking at dialysis initiation was associated with higher 3-mo mortality risk (aOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.34 to 1.53) compared with no help needed; patients who died within 3 mo were more likely to have dementia compared with patients who did not die (8% versus 5.6%; P<0.001) |

HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; WHO, World Health Organization; CKM, conservative kidney management; HGS, handgrip strength; aRR, adjusted relative risk; KT, kidney transplantation.

All reported hazard ratios, odds ratios, and relative risks are adjusted for at least age and sex.

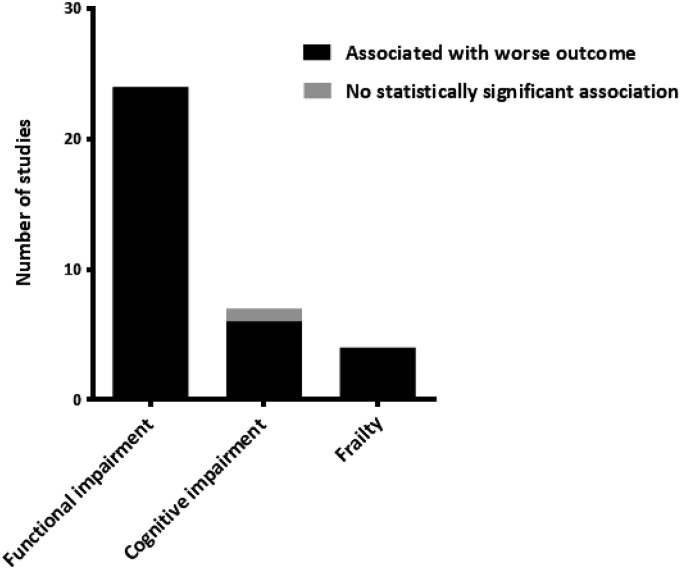

Association of Functional or Cognitive Impairment and Frailty with Outcome

In 34 of 35 (97%) associations reported in the 30 included studies, functional or cognitive impairment and frailty were significantly associated with a higher risk of adverse health outcomes, independent of calendar age (Figure 2). In all studies that used multivariate analysis (n=24), the reported associations remained statistical significant in multivariate models that included other known risk factors of poor outcome in patients with ESRD, such as cardiovascular disease and laboratory results.

Figure 2.

Associations of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with risk of adverse health outcomes in patients reaching ESRD. No studies reported functional and cognitive impairment or frailty to be associated with a lower risk of adverse health outcomes.

Functional Impairment.

Twenty-four studies reported on measurements of functional impairment, including 13 on overall functional performance, nine on mobility, and two on handgrip strength (HGS) (Table 2).

Overall functional performance was assessed in 13 studies, with eight using the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) (19–26), one using the basic Activities of Daily Living scale (27), two using the World Health Organization performance scale (28,29), and two using a composite variable for assistance with daily living (30,31). Eight studies reported on the prevalence of functional impairment in patients reaching ESRD measured as impaired overall functional performance, which ranged from 21% to 85% (19,20,23,25–27,29,30). In all 13 studies, reduced functional performance was associated with a higher risk of adverse health outcomes, both after starting dialysis and CKM. In the study by Chandna et al. (19), median survival after dialysis initiation in dependent patients (KPS=10–40) was 7.2 months, and patients requiring assistance (KPS=50–70) was 44.3 months. Every 10 points lower on the KPS score was associated with a 21% higher mortality risk (19).

The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients reaching ESRD was 7%–34% among the included studies (32–39). Nine studies addressed mobility, and all nine reported immobility to be significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality, independent of sex and calendar age (32–40). Mobility status was assessed in all studies by using data on whether the patient was dependent for transfers and walking without objectifying actual mobility (for instance, by measuring gait speed). Three large studies, in which a national registry database was used to develop and validate a prognostic screening tool for survival in older patients initiating dialysis, found mobility to be a strong predictor for early as well as 3-year mortality (34,36,37). Couchoud et al. (37) reported the overall 3-month mortality to be 10.4% among 12,500 patients on incident dialysis ≥75 years old. Impaired mobility was found to be the strongest indicator for early mortality among all clinical risk factors, including calendar age and comorbidity, with total dependency for transfers being independently associated with 3-month mortality (adjusted OR, 6.53; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 5.38 to 7.92) (37).

Only two studies used more objective assessment of physical performance by measuring HGS (41,42). In 330 patients, lower HGS (<20 kg in women and <30 kg in men) at dialysis initiation was found to be significantly associated with a higher mortality risk compared with those with appropriate HGS (adjusted HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.94) (41).

Cognitive Impairment.

Four of five studies (80%) that reported on a clinical diagnosis of dementia before dialysis initiation found dementia to be significantly associated with adverse health outcomes (30,40,43,44). In addition, three studies assessed the presence of severe behavioral disorders in patients initiating dialysis, which could include dementia, but they did not separately report on dementia in association with the outcome (34,36,37). A large study in 272,024 patients on incident dialysis showed that, in patients with dementia, the 2-year survival rate was 24% versus 66% for patients without dementia (P<0.001) (40). Kurella Tamura et al. (43) assessed functional status trajectory after dialysis initiation in nursing home residents, and they found that, by 12 months, 58% had died and that functional status had been maintained in only 13%. The presence of dementia at dialysis initiation was independently associated with lower odds of maintained functional status 12 months after start of dialysis (adjusted OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9) in a fully adjusted model (43). Only one study, in 144 octogenarians, did not find an association between dementia and poor outcome (21).

Two studies addressed depression, and both found a history of clinical depression to be significantly associated with a higher mortality risk after dialysis initiation (25,26).

Frailty.

Four studies assessed frailty and reported a high prevalence of frailty among patients on incident dialysis ranging from 32% to 79% (45–48). Frailty was measured using different instruments, including two studies using (modified) Fried criteria for frailty (45,46), one using the Clinical Frailty Scale (47), and one using the Groningen Frailty Indicator (48). All four studies found a positive association of the presence of frailty with adverse health outcomes. Frailty at dialysis initiation was associated with a higher risk of mortality (45–48) and hospitalization (45,46,48), independent of age and other possible risk factors for poor outcome. In the largest study in 2275 patients on incident dialysis of all ages, frailty as measured using a modification of Fried criteria for frailty was associated with higher risk of death within 1 year in a fully adjusted model (adjusted HR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.60 to 3.15) (45).

Quality Assessment

The overall study quality assessed by the modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale was moderate to good (Table 3). Overall, there were few concerns regarding the validity of the geriatric assessment tools used, the determination of outcome, or the reporting of the duration of follow-up. In 25 studies (83%), the association between a geriatric impairment at baseline and outcome was examined in a preselected population, in which the decision for a certain treatment modality had already been made (e.g., patient on incident dialysis or patients with CKM).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included studies on the basis of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (18)

| Publication | Selection | Comparability of Cohorts | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Representativeness of the Exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Outcome Not Present at Start of Study | Assessment of Outcome | Sufficient Duration of Follow-Up | Adequacy of Follow-Up | |

| Alfaadhel et al. (47) | 2015 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Arai et al. (35) | 2014 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bao et al. (46) | 2012 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Bowling et al. (31) | 2015 | +/− | + | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Carlson et al. (23) | 1987 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Chandna et al. (19) | 1999 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Couchoud et al. (36) | 2009 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Couchoud et al. (37) | 2015 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Decourt et al. (38) | 2016 | +/− | +/− | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Doi et al. (29) | 2015 | +/− | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Dusseux et al. (34) | 2015 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Glaudet et al. (33) | 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hussain et al. (28) | 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + |

| Isoyama et al. (41) | 2014 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Johansen et al. (45) | 2007 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | ? | ? |

| Joly et al. (21) | 2003 | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + |

| Krishnan et al. (39) | 2015 | +/− | − | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Kurella et al. (32) | 2007 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Kurella Tamura et al. (43) | 2009 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | − |

| Lopez Revuelta et al. (24) | 2004 | +/− | + | + | NA | + | + | − |

| Mauri et al. (20) | 2008 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| McClellan et al. (25) | 1991 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Meulendijks et al. (48) | 2015 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Murtagh et al. (22) | 2011 | + | + | + | − | + | + | ? |

| Park et al. (44) | 2015 | +/− | +/− | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Rakowski et al. (40) | 2006 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Shum et al. (27) | 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Soucie et al. (26) | 1996 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | ? |

| Stenvinkel et al. (42) | 2002 | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| Thamer et al. (30) | 2015 | + | +/− | + | NA | + | + | + |

For a detailed description of the separate items, please see the Supplemental Material. +, present or adequate; −, absent or inadequate; NA, not available; ?, no description.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 30 studies that addressed 35 associations of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty with adverse health outcomes in patients reaching ESRD. Functional and cognitive impairment and frailty were highly prevalent and in 34 of 35 (97%) associations, significantly associated with adverse health outcomes after initiation of RRT or CKM. The associations were independent of calendar age and other known risk factors for poor outcome.

Although the number of studies that we identified was limited, the vast majority of studies reported on a significant association of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse outcomes. These associations have repetitively been shown in nonrenal patients as well as community–dwelling older people (9–11,49–53). Although older age has been associated with decreased survival in patients on dialysis (54–57), other studies found that age alone was not an independent predictor of outcome (58,59). In this review, all reported associations of functional or cognitive impairment or frailty with adverse outcomes were independent of calendar age.

Patients with ESRD behave like a much older cohort in the general population (47), reflecting a higher biologic age. This aging is highlighted by the included studies reporting on the high prevalence of frailty (32%–79%) in patients on incident dialysis compared with studies in the community–dwelling older population, in which only 7% of people >65 years old were shown to be frail (60). The high prevalence of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty in this review is consistent with previous findings among patients with early-stage CKD and patients on dialysis (5,6,61), and it has been suggested to result from renal disease–associated changes, including protein-energy wasting, inflammation, and metabolic disturbances (62). In addition, cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension) that often play a role in the etiology of ESRD can also contribute to the development of frailty and other geriatric conditions (63). However, the fact that we found the associations of geriatric conditions with outcome to be independent of calendar age and other risk factors implies that these conditions not only result from known risk factors for poor outcome. Therefore, there may be added value for risk stratification on the basis of measuring these parameters in patients reaching ESRD, because they may be more reliable markers of biologic age.

Calendar age may not be a contraindication for starting RRT, whereas in the presence of functional or cognitive impairments or frailty, the benefits of RRT are less clear, and conservative nondialysis care may be an alternative (36,64), although a formal comparative trial has never taken place. This is consistent with recent guidelines from the Renal Physicians Association Working Group regarding the decision for renal treatment modality, which included functional impairment (e.g., KPS score <40) as one of the factors supporting the decision to withhold or withdraw dialysis (65). Nevertheless, practice guidelines do not recommend routine assessment of functional or cognitive impairments or frailty yet, even in high–risk older patients with ESRD.

The results of this review support the need for a geriatric assessment including measurements of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty in older patients when considering dialysis. Information obtained by this geriatric assessment could be useful for risk stratification and thereby, lead to more realistic expectations in patients and families of the different treatment options, which is crucial for shared decision making about whether to start dialysis. Finally, identifying functional and cognitive impairments or frailty in patients reaching ESRD gives the opportunity for rehabilitation interventions aimed at mitigating the identified geriatric impairment, which might consequently reduce the risk of poor outcome (56).

Several well established geriatric measurements were very infrequently reported in the studies in this review. Objective measures of physical performance, such as gait speed, have firmly been established as predictors of poor outcome in older adults in general (11). Furthermore, cognitive impairment and mood disturbances are common in patients with ESRD and known to associate with survival in patients on dialysis (66). Because studies of patients reaching ESRD are limited, these measurements are candidates for more research into their predictive values in prospective cohorts.

Mortality was the main outcome measure in 97% of the studies. No studies were identified reporting on QOL or cognitive decline as outcome measures, and only one study assessed functional status trajectory (43). Nevertheless, tailoring treatment goals in older patients is necessary (67). Therefore, future studies should focus on not only mortality but also, QOL and patient-related outcomes.

To accurately compare outcomes with different treatment modalities (RRT or CKM), a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal but is not likely to ever be conducted because of ethical reasons and feasibility. Therefore, research on prediction models using multiple geriatric measurements and end points in large, unselected populations of patients reaching ESRD would be of great clinical value. Extended (inter–)national predialysis registries including these patients could provide a solid basis for this data collection.

Most included studies were published recently, but seven studies were published more than a decade ago. Although demographics of patients with ESRD have changed over time, the independent association of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with adverse health outcomes in itself would probably not have been different. Substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, especially with respect to the geriatric measure that was used, the reported measure of association (HR, OR, and relative risk), outcome measures, and covariate adjustments, made it impossible to compare outcomes of studies in a meta-analysis.

This study has several limitations. First, interpretation of the results may be hampered by possible publication bias, because negative associations in multivariate analyses may not have been reported in the studies. Second, because of the inclusion of patients on incident dialysis in the majority of the studies, patients opting for CKM are under-represented. Therefore, the reported associations could potentially be different in an unselected population of patients reaching ESRD. However, selection bias would only be a concern when comparing outcomes between RRT and CKM.

Strengths of this review include the systematic search that we performed in several databases assessing all potentially relevant associations of functional and cognitive impairment and frailty with outcome in patients reaching ESRD. Furthermore, quality assessment of the studies was undertaken to identify potential factors hampering external validity.

Functional and cognitive impairment and frailty in patients reaching ESRD are highly prevalent and associate strongly and independently with adverse health outcomes. These measurements may, therefore, be useful for risk stratification and preventive interventions, although more research into their prognostic value is needed to firmly establish clinical usability.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Schoones for his support in the database searches.

The Institute for Evidence-Based Medicine is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health and Welfare and supported by ZonMw project 62700.3002.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13611215/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, Ayanian J, Balkrishnan R, Bragg-Gresham J, Chen JT, Cope E, Gipson D, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Jacobsen SS, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Leichtman AB, Lu Y, Molnar MZ, Morgenstern H, Nallamothu B, O'Hare AM, Pisoni R, Plattner B, Port FK, Rao P, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Selewski DT, Shahinian V, Sim JJ, Song P, Streja E, Kurella Tamura M, Tentori F, Eggers PW, Agodoa LY, Abbott K: US Renal Data System 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 66[1 Suppl 1]: Svii–S305, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Pippias M, Stel VS, Abad Diez JM, Afentakis N, Herrero-Calvo JA, Arias M, Tomilina N, Bouzas Caamaño E, Buturovic-Ponikvar J, Čala S, Caskey FJ, Castro de la Nuez P, Cernevskis H, Collart F, Alonso de la Torre R, García Bazaga ML, De Meester J, Díaz JM, Djukanovic L, Ferrer Alamar M, Finne P, Garneata L, Golan E, González Fernández R, Gutiérrez Avila G, Heaf J, Hoitsma A, Kantaria N, Kolesnyk M, Kramar R, Kramer A, Lassalle M, Leivestad T, Lopot F, Macário F, Magaz A, Martín-Escobar E, Metcalfe W, Noordzij M, Palsson R, Pechter Ü, Prütz KG, Ratkovic M, Resić H, Rutkowski B, Santiuste de Pablos C, Spustová V, Süleymanlar G, Van Stralen K, Thereska N, Wanner C, Jager KJ: Renal replacement therapy in Europe: A summary of the 2012 ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report. Clin Kidney J 8: 248–261, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella Tamura M: Incidence, management, and outcomes of end-stage renal disease in the elderly. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 252–257, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M: Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 361: 1612–1613, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, Gilbertson DT, Pederson SL, Li S, Smith GE, Hochhalter AK, Collins AJ, Kane RL: Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology 67: 216–223, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh P, Germain MJ, Cohen L, Unruh M: The elderly patient on dialysis: Geriatric considerations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 990–996, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swidler MA: Geriatric renal palliative care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 1400–1409, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowling CB, O’Hare AM: Managing older adults with CKD: Individualized versus disease-based approaches. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 293–302, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, Bild DE, Mittelmark MB, Polak JF, Robbins JA, Gardin JM: Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 279: 585–592, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, Roth C, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG, Sloss EM, Wenger NS: The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 49: 1691–1699, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, Brach J, Chandler J, Cawthon P, Connor EB, Nevitt M, Visser M, Kritchevsky S, Badinelli S, Harris T, Newman AB, Cauley J, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J: Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305: 50–58, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miskulin DC, Meyer KB, Martin AA, Fink NE, Coresh J, Powe NR, Klag MJ, Levey AS; Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study : Comorbidity and its change predict survival in incident dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 149–161, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried L, Bernardini J, Piraino B: Comparison of the Charlson Comorbidity Index and the Davies score as a predictor of outcomes in PD patients. Perit Dial Int 23: 568–573, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beddhu S, Zeidel ML, Saul M, Seddon P, Samore MH, Stoddard GJ, Bruns FJ: The effects of comorbid conditions on the outcomes of patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Am J Med 112: 696–701, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ: Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 72–79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ifudu O, Paul HR, Homel P, Friedman EA: Predictive value of functional status for mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol 18: 109–116, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen WF Jr., Lew NL, Liu Y, Lowrie EG, Lazarus JM: The urea reduction ratio and serum albumin concentration as predictors of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 329: 1001–1006, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P: The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis, 2012 Available at: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed August 1, 2015

- 19.Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ 318: 217–223, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauri JM, Clèries M, Vela E; Catalan Renal Registry : Design and validation of a model to predict early mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1690–1696, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, Nguyen AT, Touam M, Grünfeld JP, Jungers P: Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: Cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1012–1021, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall JM, Higginson IJ: End-stage renal disease: A new trajectory of functional decline in the last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 59: 304–308, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson DM, Johnson WJ, Kjellstrand CM: Functional status of patients with end-stage renal disease. Mayo Clin Proc 62: 338–344, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López Revuelta K, García López FJ, de Alvaro Moreno F, Alonso J: Perceived mental health at the start of dialysis as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease (CALVIDIA Study). Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 2347–2353, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClellan WM, Anson C, Birkeli K, Tuttle E: Functional status and quality of life: Predictors of early mortality among patients entering treatment for end stage renal disease. J Clin Epidemiol 44: 83–89, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soucie JM, McClellan WM: Early death in dialysis patients: Risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2169–2175, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shum CK, Tam KF, Chak WL, Chan TC, Mak YF, Chau KF: Outcomes in older adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease: Comparison of peritoneal dialysis and conservative management. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 308–314, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L: Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med 27: 829–839, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doi T, Yamamoto S, Morinaga T, Sada KE, Kurita N, Onishi Y: Risk score to predict 1-year mortality after haemodialysis initiation in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease under predialysis nephrology care. PLoS One 10: e0129180, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thamer M, Kaufman JS, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Cotter DJ, Bang H: Predicting early death among elderly dialysis patients: Development and validation of a risk score to assist shared decision making for dialysis initiation. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 1024–1032, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowling CB, Zhang R, Franch H, Huang Y, Mirk A, McClellan WM, Johnson TM 2nd, Kutner NG: Underreporting of nursing home utilization on the CMS-2728 in older incident dialysis patients and implications for assessing mortality risk. BMC Nephrol 16: 32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glaudet F, Hottelart C, Allard J, Allot V, Bocquentin F, Boudet R, Champtiaux B, Charmes JP, Ciobotaru M, Dickson Z, Essig M, Honoré P, Lacour C, Lagarde C, Manescu M, Peyronnet P, Poux JM, Rerolle JP, Rincé M, Couchoud C, Aldigier JC; REIN Limousin : The clinical status and survival in elderly dialysis: Example of the oldest region of France. BMC Nephrol 14: 131, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dusseux E, Albano L, Fafin C, Hourmant M, Guérin O, Couchoud C, Moranne O: A simple clinical tool to inform the decision-making process to refer elderly incident dialysis patients for kidney transplant evaluation. Kidney Int 88: 121–129, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai Y, Kanda E, Kikuchi H, Yamamura C, Hirasawa S, Aki S, Inaba N, Aoyagi M, Tanaka H, Tamura T, Sasaki S: Decreased mobility after starting dialysis is an independent risk factor for short-term mortality after initiation of dialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 227–233, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, Allot V, Esnault V, Frimat L, Stengel B; French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry : A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1553–1561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Couchoud CG, Beuscart JB, Aldigier JC, Brunet PJ, Moranne OP; REIN registry : Development of a risk stratification algorithm to improve patient-centered care and decision making for incident elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 88: 1178–1186, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decourt A, Gondouin B, Delaroziere JC, Brunet P, Sallée M, Burtey S, Dussol B, Ivanov V, Costello R, Couchoud C, Jourde-Chiche N: Trends in survival and renal recovery in patients with multiple myeloma or light-chain amyloidosis on chronic dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 431–441, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnan M, Weinhandl ED, Jackson S, Gilbertson DT, Lacson E Jr.: Comorbidity ascertainment from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report and Medicare claims around dialysis initiation: A comparison using US Renal Data System data. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 802–812, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakowski DA, Caillard S, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC: Dementia as a predictor of mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1000–1005, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isoyama N, Qureshi AR, Avesani CM, Lindholm B, Bàràny P, Heimbürger O, Cederholm T, Stenvinkel P, Carrero JJ: Comparative associations of muscle mass and muscle strength with mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1720–1728, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenvinkel P, Barany P, Chung SH, Lindholm B, Heimbürger O: A comparative analysis of nutritional parameters as predictors of outcome in male and female ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1266–1274, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JY, Kim MH, Han SS, Cho H, Kim H, Ryu DR, Kim H, Lee H, Lee JP, Lim CS, Kim KH, Joo KW, Kim YS, Kim DK; Clinical Research Center for End Stage Renal Disease (CRC for ESRD) Investigators : Recalibration and validation of the Charlson comorbidity index in Korean incident hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 10: e0127240, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG: Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2960–2967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL: Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 172: 1071–1077, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alfaadhel TA, Soroka SD, Kiberd BA, Landry D, Moorhouse P, Tennankore KK: Frailty and mortality in dialysis: Evaluation of a clinical frailty scale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 832–840, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meulendijks FG, Hamaker ME, Boereboom FT, Kalf A, Vögtlander NP, van Munster BC: Groningen frailty indicator in older patients with end-stage renal disease. Ren Fail 37: 1419–1424, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodin MB, Mohile SG: A practical approach to geriatric assessment in oncology. J Clin Oncol 25: 1936–1944, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, Skovlund E, Audisio RA, Johannessen HO, Bakka A, Wyller TB: Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 76: 208–217, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, Newman AB, Colbert LH, Bauer DC, Satterfield S, Pavon J, Kritchevsky SB; Health, Aging and Body Composition Study : Physical performance and subsequent disability and survival in older adults with malignancy: Results from the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 76–82, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giantin V, Valentini E, Iasevoli M, Falci C, Siviero P, De Luca E, Maggi S, Martella B, Orrù G, Crepaldi G, Monfardini S, Terranova O, Manzato E: Does the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), predict mortality in cancer patients? Results of a prospective observational trial. J Geriatr Oncol 4: 208–217, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng MA, McMillan DT, Crowell K, Muss H, Nielsen ME, Smith AB: Geriatric assessment in surgical oncology: A systematic review. J Surg Res 193: 265–272, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lamping DL, Constantinovici N, Roderick P, Normand C, Henderson L, Harris S, Brown E, Gruen R, Victor C: Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs in the North Thames Dialysis Study of elderly people on dialysis: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 356: 1543–1550, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Mittleman MA, Levin R, Pliskin JS, Avorn J: Comparing mortality of elderly patients on hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: A propensity score approach. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2353–2362, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Dekker FW, Stengel B, Simpson K, Briggs JD; ERA-EDTA Registry Committee : The epidemic of aging in renal replacement therapy: An update on elderly patients and their outcomes. Clin Nephrol 60: 352–360, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Létourneau I, Ouimet D, Dumont M, Pichette V, Leblanc M: Renal replacement in end-stage renal disease patients over 75 years old. Am J Nephrol 23: 71–77, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villar E, Remontet L, Labeeuw M, Ecochard R: Effect of age, gender, and diabetes on excess death in end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2125–2134, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 32[Suppl 3]: S112–S119, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group : Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: M146–M156, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smyth A, Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Mulqueen J, Canavan M, Reddan DN, O’Donnell M: Mild chronic kidney disease and functional impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing 42: 488–494, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JC, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD: Frailty and protein-energy wasting in elderly patients with end stage kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 337–351, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker SR, Wagner M, Tangri N: Chronic kidney disease, frailty, and unsuccessful aging: A review. J Ren Nutr 24: 364–370, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K: Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2002–2009, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Renal Physicians Association : Shared Decision Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA: Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int 74: 930–936, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mooijaart SP, Broekhuizen K, Trompet S, de Craen AJ, Gussekloo J, Oleksik A, van Heemst D, Blauw GJ, Muller M: Evidence-based medicine in older patients: How can we do better? Neth J Med 73: 211–218, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.