Abstract

3-Nitrotyrosine (3NT) in liver proteins of mice treated with hepatotoxic doses of acetaminophen (APAP) has been postulated to be causative in toxicity. Nitration is by a reactive nitrogen species formed from nitric oxide (NO). The source of the NO is unclear. iNOS knockout mice were previously found to be equally susceptible to APAP toxicity as wildtype mice and iNOS inhibitors did not decrease toxicity in mice or in hepatocytes. In this work we examined the potential role of nNOS in APAP toxicity in hepatocytes using the specific nNOS inhibitor NANT (10µM)(N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]pentyl]-N'-nitroguanidinetris (trifluoroacetate)). Primary hepatocytes (1 million/ml) from male B6C3F1 mice were incubated with APAP (1mM). Cells were removed and assayed spectrofluorometrically for reactive nitrogen and oxygen species using diaminofluorescein (DAF) and Mitosox red, respectively. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release into media. Glutathione (GSH, GSSG), 3NT, GSNO, acetaminophen-cysteine adducts, NAD, and NADH were measured by HPLC. APAP significantly increased cytotoxicity at 1.5–3.0 h. The increase was blocked by NANT. NANT did not alter APAP mediated GSH depletion or acetaminophen-cysteine adducts which indicated that NANT did not inhibit metabolism. APAP significantly increased spectroflurometric evidence of reactive nitrogen and oxygen formation at 0.5 and 1.0 h, respectively, and increased 3NT and GSNO at 1.5–3.0 h. These increases were blocked by NANT. APAP dramatically increased NADH from 0.5–3.0 h and this increase was blocked by NANT. Also, APAP decreased the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR), decreased ATP production, and caused a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which were all blocked by NANT.

Keywords: Nitric Oxide, Reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, hepatotoxicity, 3-nitrotyrosine, S-nitrosoglutathione, mitochondria, acetaminophen

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Acetaminophen (paracetamol, APAP; N-acetyl-p-aminophenol) is the most widely used analgesic/antipyretic drug in the world. APAP is believed to be safe at therapeutic doses but produces hepatic centrilobular necrosis when an overdose occurs [1]. In the United States approximately 500 deaths occur annually from APAP overdose [2]. The initial metabolic events in APAP toxicity have been well described. Hepatic metabolism of APAP by cytochrome P450 to the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) is the initial event [3]. Glutathione (GSH) efficiently detoxifies NAPQI after a therapeutic dose but when an overdose occurs GSH is depleted [4, 5] and the metabolite covalently binds with hepatic cellular proteins to form 3-(cystein-S-yl)-acetaminophen (APAP-Cys) adducts [6]. The covalent binding of the hepatic proteins correlates with hepatic toxicity. The mode of cell death induced by APAP toxicity is necrosis. Previously, we reported the presence of nitrated tyrosine (3-nitrotyrosine) in hepatic proteins of APAP-treated mice, which coincided with the presence of APAP-Cys adducts in centrilobular hepatocytes and developing necrosis [7]. It was postulated that 3-nitrotyrosine was formed by nitration of tyrosine by peroxynitrite, a highly reactive species generated from superoxide and nitric oxide (NO) [8–10]. Peroxynitrite is a nitrating and oxidizing agent. Peroxynitrite is detoxified by GSH [11] which is depleted in APAP toxicity [4]. A number of major proteins have been reported to be nitrated in murine APAP toxicity, including MnSOD [12], mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, glutathione peroxidase, ATP synthase, and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase [13]. Importantly, Abdelmegeed et al., found that inhibition of APAP toxicity by N-acetylcysteine treatment decreased protein nitration [13].

Kon et al. [14] and Reid et al. [15] reported that mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) occurs in APAP toxicity in hepatocytes. MPT is an abrupt increase in the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane to ions and small molecular weight solutes. It is promoted by oxidative stress as well as nitrosative stress. It results in the inability of the mitochondria to produce adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) and is a lethal event for cells [16, 17]. APAP induced MPT has been postulated to be mediated by increased peroxynitrite resulting in nitration of proteins [18]. Since inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; NOS2) is present in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, [19] it was initially postulated to be the source of NO. However, both iNOS knockout and wild-type mice were found to be equally sensitive to APAP toxicity [20, 21]. Decreased APAP hepatotoxicity was not observed in mice treated with pharmacological inhibitors of iNOS [18, 22], suggesting iNOS was not involved in APAP toxicity. However, the neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS; NOS1) inhibitor 7-nitroindazole did inhibit APAP toxicity and nitration when added in the late phase of toxicity and nNOS has been previously reported to be present in hepatocytes [23].

In this work experiments were performed to develop a greater understanding of early events important in APAP toxicity in hepatocytes. A highly selective inhibitor of nNOS (Ki = 120nM), N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]pentyl]-N’-nitroguanidinetris(trifluoroacetate) (NANT) was utilized to determine its effect on APAP toxicity. The chemical structure of NANT suggested that it would not inhibit CYP (cytochrome P450), enabling reactive nitrogen formation as it relates to APAP toxicity to be examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and suppliers

Acetaminophen (APAP; 4-acetamidophenol), Hepes, heparin sodium salt grade I-A from porcine intestinal mucosa, penicillin G sodium salt, RPMI-1640 modified media with L-glutamine and without sodium bicarbonate and phenol red, Percoll, 0.4% trypan blue solution, GSH, GSSG, GSNO, 3NT, NAD, NADH were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA). N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino] pentyl]-N’- nitroguanidinetris (trifluoroacetate) (NANT) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Collagenase A from Clostridium histolyticum was obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA). 4-Amino-5-Methylamino-2',7'-Difluorofluorescein Diacetate (DAF-FM), MitoSOX red and JC1 were purchased from Life technologies (Eugene, OR, USA). Cytotoxicity detection kit (LDH) was obtained from Roche Diagnostic Corporation (Indianapolis, IN, USA). ATP Bioluminescent Assay kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals

Male six-week old B6C3F1 mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All animal experimentation and protocols were approved by University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Mice were acclimated one week prior to the experiments and fed ad libitum until the time of sacrifice.

Hepatocyte isolation and incubations

Freshly isolated hepatocytes were obtained from mice by collagenase perfusion as previously described [18]. Hepatocytes yielding >40 million cells and cell viability >90% as determined by Trypan blue exclusion were used for the experiments. The hepatocytes were incubated at a concentration of 1 million cells/ml in RPMI 1640 media (supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 10 IU heparin/ml, and 500 IU penicillin G/ml) in 125 ml Erlenmeyer flasks at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% O2-5% CO2. APAP (1 mM) was added to experimental hepatocytes [18]; no APAP was added to the control flasks. Other experimental and control flasks contained 10 µM NANT. The toxicity data were obtained from three to four separate incubations that were performed on separate mice on different days.

Toxicity assays

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a stable cytoplasmic enzyme present in all cells. It is rapidly released into the cell culture supernatant upon damage of the plasma membrane. Briefly, the hepatocytes were separated from the media by centrifugation. To each sample media (100 µl), reaction mixture from the kit (100 µl) was added followed by incubation in a heating bath at 37°C for 30 mins. During this incubation period the mixture was protected from light. The absorbance of samples was determined spectrophotometrically in a Bio-rad 550 plate reader at a wavelength of 490 nm and cytotoxicity values determined.

Fluorescence assays

Increased fluorescence of MitoSOX Red was used as an assay for reactive oxygen as previously described [24]. Even though the increased fluorescence is commonly used as an assay for superoxide, the assay is not specific. The increased fluorescence may also be catalyzed by hydrogen peroxide plus a peroxidase, or other intracellular processes [25]. Thus, the increased fluorescence is an assay for reactive oxygen. 4-Amino-5-Methylamino-2',7'-Difluorofluorescein Diacetate (DAF-FM) was used to assay for reactive nitrogen (NO) [25]. Briefly, 1 ml aliquots of hepatocytes were centrifuged at 140 g for 2 min and supernatant discarded. The hepatocytes were resuspended with DAF-FM (10µM) or MitoSOX (5µM) in 2ml of phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 20 min at 37°C in atmosphere of 95% O2-5% CO2. Following incubation, cells were centrifuged and washed free of excess of dye, resuspended in 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, and excited/emitted at 495/515 nm for DAF-FM and 510/580 nm for MitoSOX respectively using SpectraMax M2e fluorescence spectrophotometer.

HPLC assays

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to quantify the reduced as well as oxidized glutathione, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT). Approximately 2 million hepatocytes were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. To precipitate proteins, 10% metaphosphoric acid was added to the homogenate and incubated for 30 min on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 18,000 g at 4°C for 15 min, and 20 µl of the resulting supernatants were injected into the HPLC column for metabolite quantification, while the pellet was used for protein analysis using BCA protein assay. The methodological details for HPLC elution and electrochemical detection of free unbound GSH, GSSG, GSNO and 3-NT in proteins (hydrolyzed by 6N HCl treatment) have been described previously described [26]. NAD+ and NADH were measured utilizing a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC-UV system [27]. APAP covalently bound to proteins in hepatocytes was measured by protease treatment of hepatocyte homogenates followed by high performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical analysis for APAP-cysteine as previously described [28].

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in hepatocytes

The Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured at 37°C using an XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA, USA) as previously described with minor modifications from Pathak et al. [29]. Briefly, 8,000 freshly isolated hepatoyctes/well were plated in CellTak coated plates, using unbuffered DMEM supplemented with 4 mM Glutamate and incubated in a non-CO2 incubator for 1 h at 37°C. Three baseline measurements were acquired before sequential injection of NANT (10 µM) and APAP (1 mM). Oxygen consumption rates were calculated by the Seahorse XF-96 software and represent an average of 20–32 measurements on two different days (10–16 wells per mouse per day) [29].

Mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production

A mitochondrial membrane specific cationic dye JC1 was used to determine the relative mitochondrial membrane potential. Based on high negative membrane potential, JC1 enters mitochondria. JC1 emits fluorescence as monomer at 535 nm indicating a low membrane potential, whereas when it aggregates at 590 nm a high membrane potential is indicated. Briefly, hepatocytes of 2ml aliquots were centrifuged at 140 g for 2 min and supernatant discarded. Cells were resuspended with 6.5 µM JC1 in 3 ml JC1 buffer and incubated for 25 min at 37°C in atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Following incubation, cells were centrifuged and washed of excessive dye and resuspended in 2 ml JC1 buffer and excited at 490nm and emitted at 530 and 590 nm. The ratio of the reading at 590 nm to reading at 530 nm (590:530 ratio) was considered as the relative mitochondrial membrane potential [15, 30].

Adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) production in isolated hepatocytes was measured following the manufacturer’s protocol, using a TD20/20 luminometer (Turner Design, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Quantification of ATP was made by interpolation from an ATP standard curve.

Statistical analyses

Analysis of variance was performed with a Bonferroni post hoc test using the Prism GraphPad 6.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, Ca, USA). Statistical significance was defined as experimental being p < 0.05 from control.

RESULTS

Effect of NANT on APAP toxicity and metabolic activation

NANT has been reported to be a highly specific inhibitor of nNOS [31, 32]. The effect of NANT on freshly isolated hepatocytes was investigated to determine the role of nNOS in APAP toxicity. As shown in Figure 1A, toxicity significantly increased in APAP treated hepatocytes, as determined by the increase in LDH in the media at 1.5–3 h compared to control hepatocytes. Addition of 10 µM NANT eliminated toxicity produced by APAP.

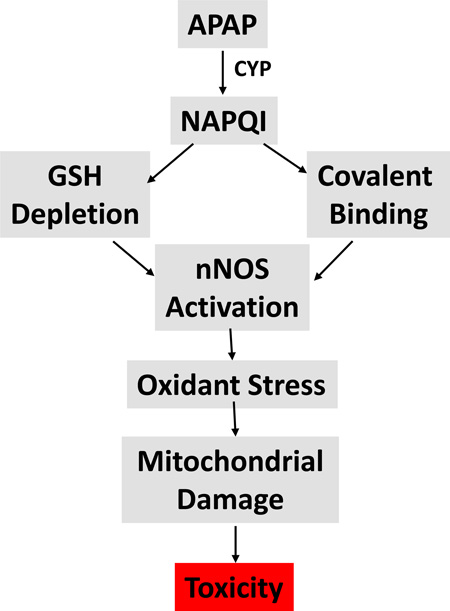

Figure 1.

Effect of NANT on APAP-induced toxicity, glutathione, and covalent binding in freshly isolated hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were incubated with APAP (1 mM), APAP plus NANT (10 uM), NANT alone or with media alone (Con) for 0–3h. Time points were taken, (A) relative toxicity was measured using LDH release, (B) GSH, (C) APAP-Cys, and (D) GSSG in the hepatocytes. Significant increase was indicated by * (p≤0.05) from control group. Samples were n=3 from 3 separate mice and hepatocytes isolated on 3 different days. The data are presented as mean ± SE.

The importance of APAP metabolism by CYP enzymes to the reactive metabolite NAPQI and its role in GSH depletion and covalent binding are well described [1]. Since CYP inhibition of APAP metabolic activation is known to decrease toxicity, the effect of NANT on GSH depletion and covalent binding was determined. As anticipated, GSH levels were depleted by 70% in the APAP treated hepatocytes by 0.5 h (Figure 1B). NANT did not significantly alter the APAP mediated GSH depletion. The finding that GSSG levels were not highly increased compared to the total amount of GSH in the hepatocytes (Figure 1D) is consistent with the previous report that the mechanism of GSH depletion in APAP toxicity is coupled with the reactive metabolite NAPQI and not oxidative stress [33]. The reactive metabolite NAPQI covalently binds to cysteine groups on proteins forming APAP-Cys adducts. As shown in Figure 1C, NANT did not alter covalent binding of APAP to protein. These data, in addition to the GSH depletion results, indicate that the mechanism by which NANT decreased APAP toxicity in hepatocytes was not through inhibition of CYP metabolism to NAPQI and its subsequent role in GSH depletion and APAP-Cys adduct formation.

Effect of NANT on formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species

To further understand the role of nNOS mediated NO formation in APAP toxicity, 3-nitrotyrosine in hepatocyte proteins was quantified. As shown in Figure 2A, 3-nitrotyrosine levels in proteins were significantly increased at 1.5 h in APAP treated hepatocytes compared to control hepatocytes. NANT significantly decreased the formation of 3-nitrotyrosine in the hepatocyte proteins treated with APAP compared to APAP only treated hepatocytes.

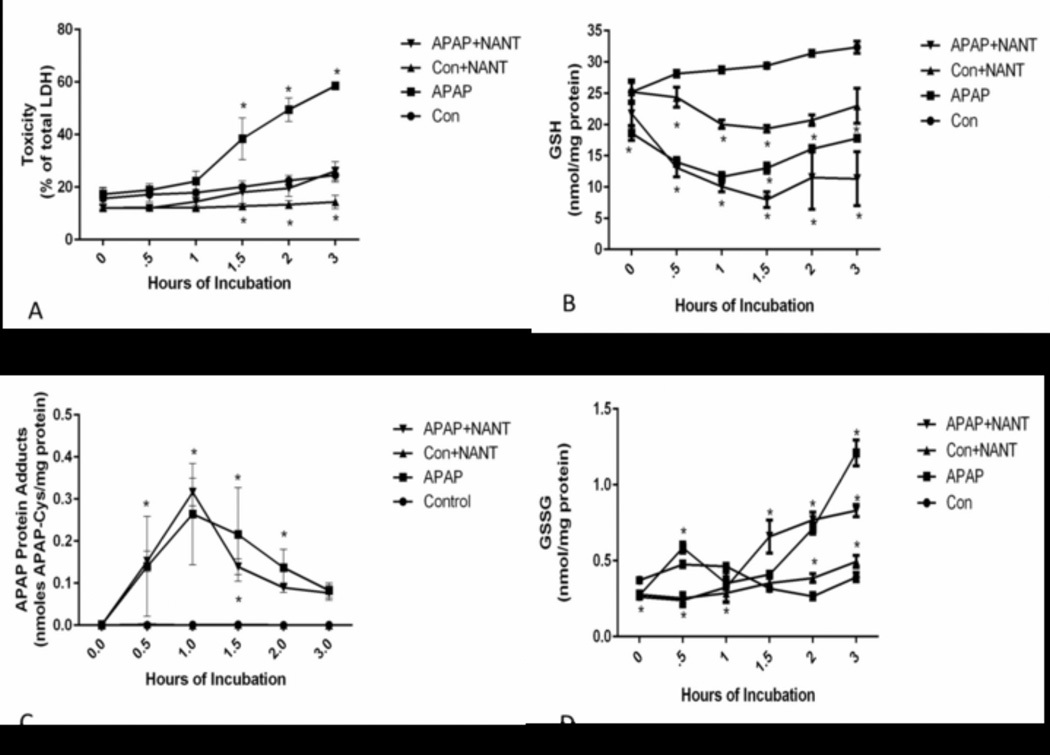

Figure 2.

Effect of NANT on APAP-induced reactive oxygen and nitrogen formation in freshly isolated hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were incubated with APAP (1mM), APAP plus NANT (10uM), NANT alone or with media alone (Con) for 0–3 h. Time points were taken, (A) 3-NT in proteins, (B) Nitric Oxide production (C) Reactive Oxygen production, and (D) GSNO in the hepatocytes. Significant increase was indicated by * (p≤0.05) from control group. Samples were n=3 from 3 separate mice and hepatocytes isolated on 3 different days. The data are presented as mean ± SE

Subsequently, the effect of APAP treatment on reactive nitrogen (NO) levels was examined in hepatocytes. NO levels remained at base line levels for 0–3 h in freshly isolated control hepatocytes. Treatment of hepatocytes with APAP caused a dramatic increase in NO at 0.5 h, returning to control levels at 1 h, and persisting at control levels for the duration. NANT subsequently decreased the APAP induced increase in NO to control levels at 1–3 h. (Figure 2B).

The effect of NANT on formation of reactive oxygen (superoxide anion plus other reactive oxygen species) was also examined using increase in Mitosox fluorescence. Mitosox fluorescence was found to be significantly higher in the APAP treated hepatocytes at 1 h compared to control hepatocytes (Figure 2C) and decreased to control levels at 1.5–3 h. Interestingly, in the presence of NANT, mitosox fluorescence was significantly inhibited in the APAP treated hepatocytes.

The formation of GSNO was also quantified in the hepatocytes. This species is a nitrosylating agent; nitrosylation is believed to be a post-translational protein modification important in cell signaling [34]. As shown in Figure 2D, GSNO was significantly increased in the APAP treated hepatocytes at 1.5–3 h. Its formation was significantly reduced by NANT.

Effect of NANT on NAD+ and NADH

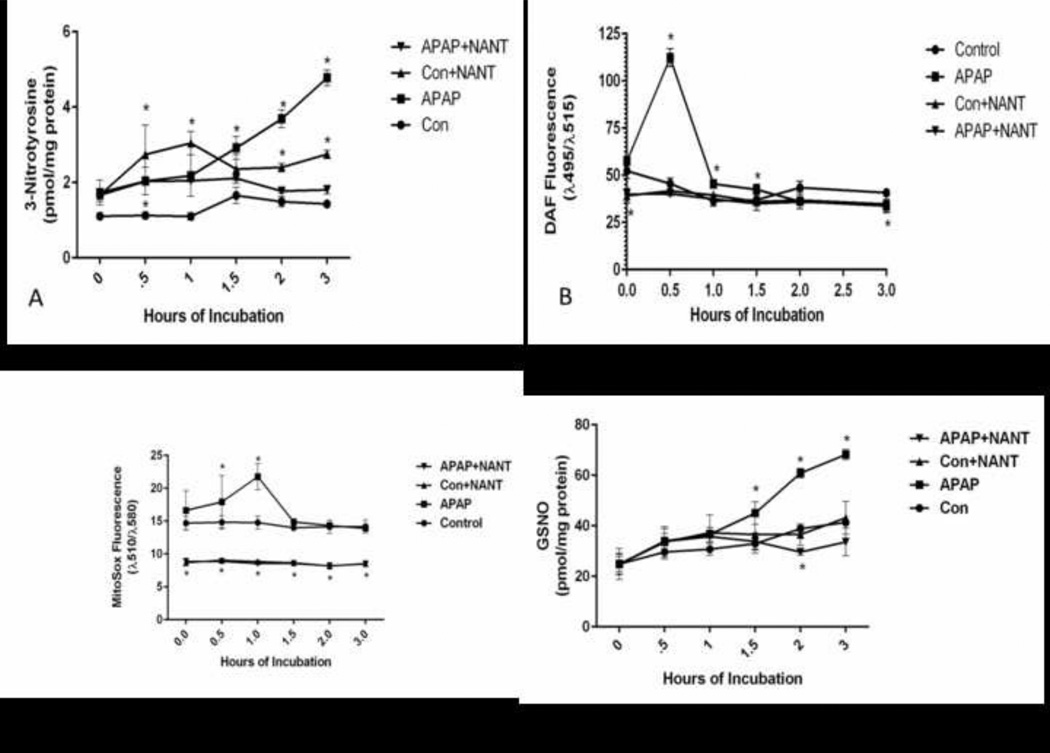

The effect of APAP on NADH and NAD+ levels in the hepatocytes was examined. Hepatocytes treated with APAP were found to have significantly higher levels of NADH at 0.5 h. The higher levels continued through the 3 h incubation period (Figure 3A). NANT blocked the APAP induced increase in NADH levels at 0–3 h. NANT caused significantly lower levels of NAD+ in control hepatocytes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of NANT on APAP-induced NAD and NADH levels in freshly isolated hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were incubated with APAP (1 mM), APAP plus NANT (10 uM), NANT alone and with media alone (Con) for 0–3h. Time points were taken, (A) NADH and (B) NAD+ in the hepatocytes. Significant increase was indicated by * (p≤0.05) from control group. Samples were n=3 from 3 separate mice and hepatocytes isolated on 3 different days. The data are presented as mean ± SE.

Effect of NANT on Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR), mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production

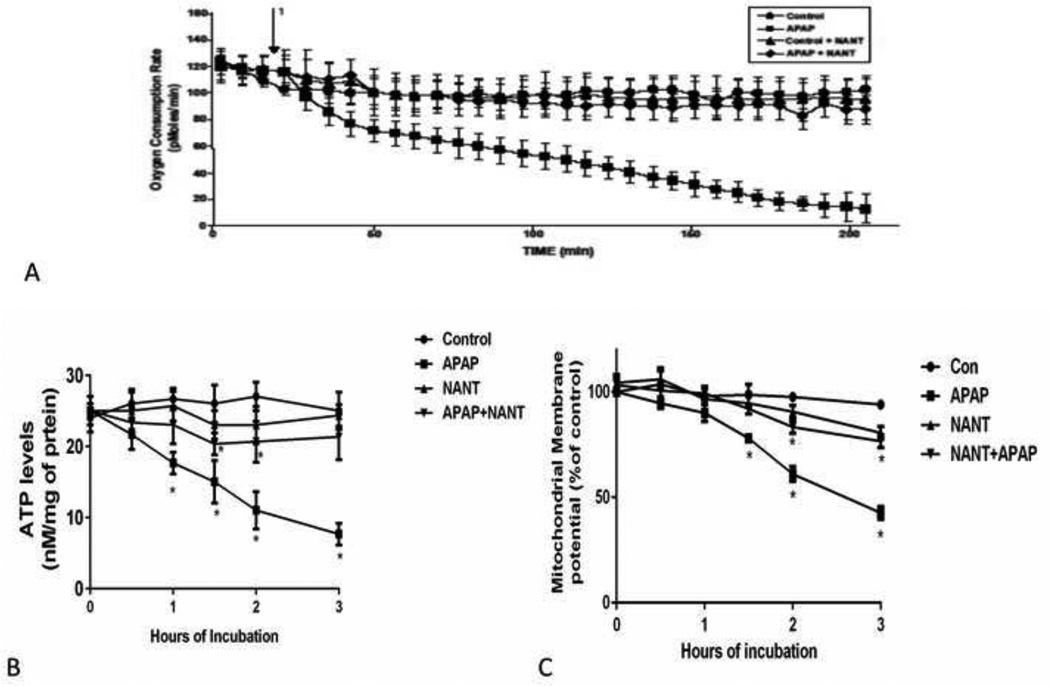

The effect of APAP on OCR was determined using an extracellular flux analyzer. A considerable decrease in OCR was observed between 0 and 0.5 h in both control and APAP treated hepatocytes. APAP treated hepatocytes had a gradual decrease in OCR between 1 and 3 h (Figure 4A), which was blocked by NANT treatment. The decreased OCR corresponds with the development of toxicity in hepatocytes (Figure 1A), which is blocked by nNOS inhibition.

Figure 4.

Effect of NANT on APAP-induced alterations of oxygen consumption, mitochondrial membrane potential, and ATP levels in freshly isolated hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were incubated with APAP (1 mM), APAP plus NANT (10 uM), NANT alone and with media alone (Con) for 0–3 h. OCR (A) in the above mention groups were measured using Seahorse XF96 analyzer 1 in the graph represent the time at which APAP is injected in the groups and NANT in the groups. Time points were taken, (B) relative mitochondrial membrane potential and (C) ATP production in the hepatocytes. Significant increase was indicated by * (p≤0.05) from control group. Samples were n=3 from 3 separate mice and hepatocytes isolated on 3 different days. The data are presented as mean ± SE.

Since OCR was decreased during APAP toxicity in hepatocytes, we examined mitochondrial membrane potential in the hepatocytes. Mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly reduced in hepatocytes treated with APAP between 1.5–3 h (Figure 4B) compared to control hepatocytes. Inhibition of nNOS blocked the APAP induced mitochondrial membrane potential changes. The decreases in OCR and mitochondrial membrane potential indicate dysfunction of mitochondria. Also we examined the effect of APAP on ATP levels in the hepatocytes. ATP levels were decreased from 0.5 to 3 h in hepatocytes treated with APAP (Figure 4C), compared to control hepatocytes. NANT blocked the decrease in ATP production.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the mechanism contributing to reactive nitrogen formation and its relationship to toxicity in the early stages of APAP hepatotoxicity was the primary goal of this study. Treatment of freshly isolated hepatocytes with APAP showed increased 3NT compared to control hepatocytes. Increased levels of 3NT indicate a role for NO in APAP toxicity. Previously our laboratory reported that the nNOS inhibitor 7-nitroindazole blocked APAP toxicity in hepatocytes, whereas iNOS inhibitors had no effect [18]. Also, several laboratories, including our laboratory, showed that iNOS knockout mice were equally sensitive to APAP hepatotoxicity as wild type mice [20, 21]. In addition, we determined that pharmacological inhibitors did not decrease APAP hepatotoxicity in mice [18, 22]. In the present work, we were particularly interested in the early events occurring in APAP toxicity in hepatocytes. Previously, we examined 7-nitroindazole as a nNOS inhibitor in the late stages of APAP toxicity. This nNOS inhibitor has been reported to inhibit cytochrome P-450 [35]. Thus it cannot be utilized to investigate the early events important in APAP induced reactive nitrogen formation because it may inhibit NAPQI formation and subsequent NAPQI mediated GSH depletion and covalent binding. The specific inhibitor of nNOS, NANT, was added to the incubations at time 0. Based on the chemical structure of NANT, we hypothesized that it would not inhibit CYP activity or alter APAP induced GSH depletion and covalent binding. It was determined that NANT did not inhibit APAP induced GSH depletion (Figure 1B) or covalent binding (Figure 1C) in hepatocytes. Thus, the data indicate that NANT did not prevent toxicity through alterations in metabolic activation.

The levels of 3NT in APAP treated hepatocytes significantly increased from 1.5–3 h compared to the control hepatocytes (Fig 2A). The time dependent increase in nitration and the relative rate of nitration correlated with increases in toxicity as measured using LDH (Fig 1A). NANT’s prevention of APAP toxicity (Figure 1A) and protein nitration (Figure 2A) strongly support previous findings [18] that nNOS is an important mediator for protein nitration and toxicity. Even though 3-nitrotyrosine formation has been postulated to occur by a peroxynitrite, no definitive evidence has been presented for this pathway and, nitration may occur by other mechanisms. For example, Fenton chemistry may be important. Thomas et al. [36] showed that in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and sodium nitrate, hemin catalyzed the nitration of bovine serum albumin.

The time required for the formation of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species was of particular interest. In isolated hepatocytes, reactive nitrogen (NO) levels were increased significantly at 0.5 h as evidenced by increased DAF fluorescence and subsequently decreased to basal levels (Figure 2A). In the presence of NANT there was a blockage of NO production. These data further support the postulation that NO is synthesized from nNOS.

In addition to NO, we assayed for the effect of APAP on increased reactive oxygen formation utilizing Mitosox red. Mitosox red is converted to a fluorescent product by superoxide, but increased fluorescence may also be catalyzed by hydrogen peroxide plus a peroxidase, or other intracellular processes [25]. Mitochondria are believed to be a significant source of the reactive oxygen species superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which leak from the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Using Mitosox red we examined its increased fluorescence in isolated hepatocytes in the presence of APAP to determine the effect of NANT treatment. H epatocytes incubated with APAP had significantly higher levels of Mitosox red fluorescence by 1 h (Figure 2C) and then fluorescence returned to basal levels. Surprisingly, NANT decreased APAP induced fluorescence below basal levels. Moreover the basal level of fluorescence observed in control hepatocytes was also reduced by NANT. Thus, NO appears to be an important mediator leading to increased reactive oxygen as assayed by Mitosox red fluorescence.

Further insight into the mechanism of how NO could lead to APAP toxicity was gained by examination of the NADH/NAD levels (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3A, a large APAP mediated increase in NADH levels was observed in the hepatocytes beginning at 0.5 h and continuing through the incubation period. This increase was blocked by NANT. These data suggest that mitochondrial electron flow is blocked, resulting in an accumulation of NADH in APAP toxicity.

Other investigators have examined hepatic mitochondrial complex activities in APAP toxicity both in vitro and in vivo. In freshly isolated mouse hepatocytes Burcham and Harmon [37] found that by 1 h, 5 mM APAP significantly inhibited respiration at complexes 1 and 2 but not at complex 3. Thus, there was a significant APAP mediated decrease in oxygen utilization using glutamate plus malate plus NADH as substrates by 1 h and also a significant decrease in oxygen utilization using succinate as the substrate. Ascorbate plus TMPD (N,N,N,N-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine) did not decrease respiration. Also, they observed a time dependent decrease in cytosolic ATP levels. These events occurred before toxicity as determined by plasma membrane rupture. Similarly, respiration of mitochondria isolated from APAP treated mice showed significant decreases in the activities of Complex I and Complex II before toxicity [38].

Increased levels of NADH in APAP treated hepatocytes support the hypothesis that a dysfunctional complex I occurs in hepatocytes treated with APAP. Moreover, the data presented in this manuscript support the hypothesis that inhibition of complex I is mediated by a reactive nitrogen species. Natalia et al.[39] previously postulated that complex I is selectively sensitive to reactive nitrogen. In isolated rat liver, mitochondria in the presence of NO displayed a significant decreased rate of oxygen consumption and the inactivating mechanism was postulated to be peroxynitrite. A similar trend of decreased OCR in isolated hepatocytes incubated with APAP is consistent with a dysfunction of mitochondrial complex I. NO has been reported to induce mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen [39–41]. In our experiments NANT was able to inhibit the production of reactive oxygen in the hepatocytes treated with APAP.

The mechanism of how increased reactive nitrogen and oxygen species may produce APAP induced toxicity is unknown. Nitration of proteins is a correlate of toxicity, but specific nitrated proteins causing the toxicity have not been identified [7]. Alternatively, oxidation events may be important in toxicity. It has been hypothesized that reactive nitrogen formed in APAP toxicity may oxidize ubiquinol leading to altered mitochondrial electron flow, but no data have been presented to support this mechanism [42]. Lastly, nitrosylation may play a role in toxicity. GSNO was identified as an intermediate formed in APAP toxicity. GSNO has been reported to inhibit complex I as well as increase superoxide production from complex I. Moreover this inhibition is reversible in the presence of GSH and GSH is depleted in APAP toxicity [43]. Chang and co-workers [44] showed in isolated brain mitochondria that in presence of GSNO, S-Nitrosylation of mitochondrial protein occurs at 75 kDa which was decreased in presence of high levels of GSH. In addition, adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) and voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC-1), major components of the MPT pore complex, have been identified as two of the nitrosylated proteins [44, 45]. The importance of nitrosylation, nitration, or oxidation in APAP toxicity remains to be determined.

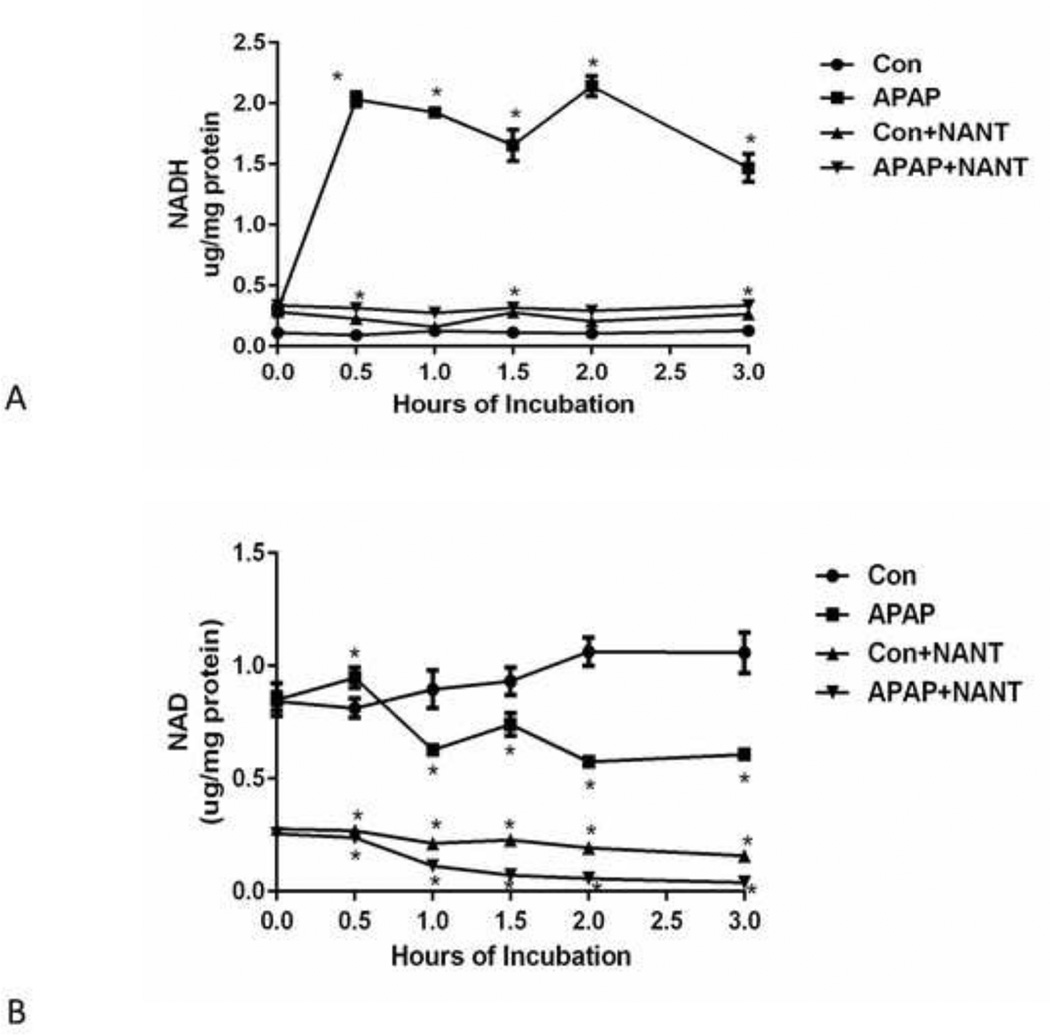

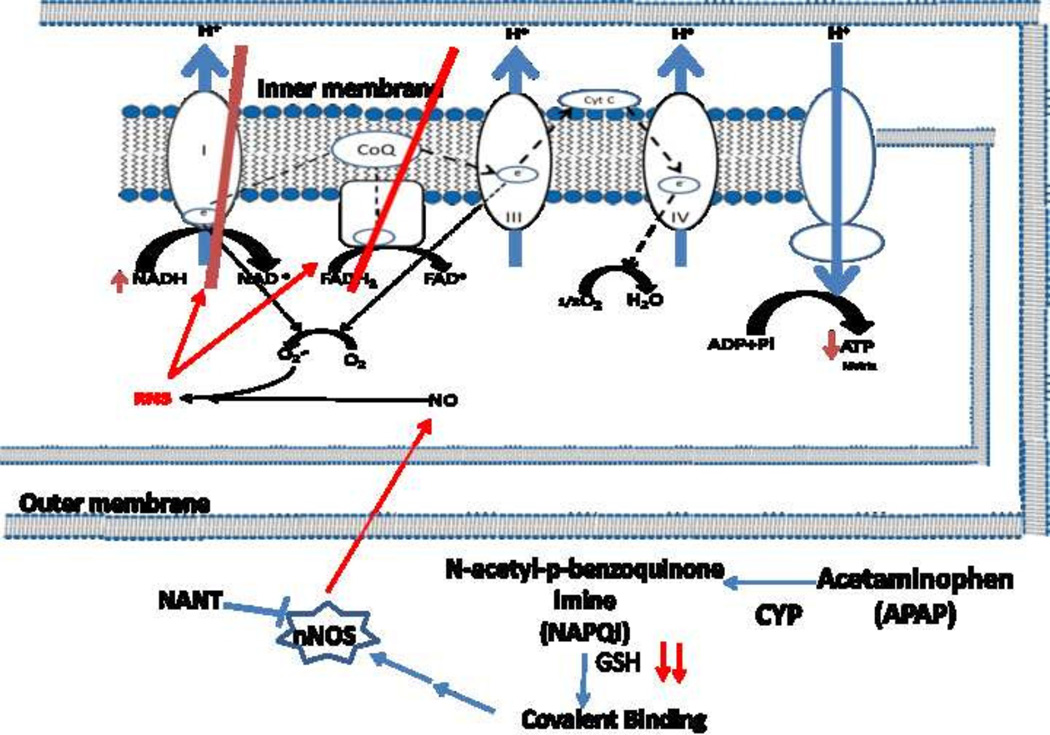

The data presented in this manuscript strongly suggest a role for nNOS in APAP mediated hepatotoxicity. However, the mechanism of how nNOS is activated is unclear. Available data indicate that a critical step in toxicity is metabolic activation of APAP to NAPQI leading to GSH depletion and covalent binding. Covalent binding occurs to a large number of proteins but covalent binding to nNOS has not been reported. However, calcium is known to activate nNOS and alteration of calcium levels in hepatocytes, possibly as a result of covalent binding, has been reported to occur in APAP toxicity [46]. Thus, alteration of calcium may be a key step between APAP metabolism and nNOS activation. The proposed mechanism of APAP toxicity mediated by nNOS is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Postulated mechanism of APAP mediated mitochondrial toxicity by RNS.

CONCLUSION

The toxicity of APAP (acetaminophen) in freshly isolated hepatocytes occurs with depletion of GSH, increased covalent binding, increased reactive nitrogen and reactive oxygen formation, and decreased mitochondrial function. The nNOS (NOS1) inhibitor NANT (N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]pentyl]-N'-nitroguanidinetris (trifluoroacetate)) blocks the increased toxicity, the increased reactive nitrogen and oxygen formation, and the loss of mitochondrial function, but does not alter the GSH depletion or the covalent binding. These data suggest that activation of nNOS is a critical step in APAP toxicity.

Highlights.

APAP hepatoxicity occurs with increased reactive nitrogen and oxygen formation.

The nNOS inhibitor NANT blocks toxicity and the increased RNS/ROS formation

Toxicity occurs with decreased oxygen consumption and ATP, and increased NADH

nNOS inhibition blocks decrease in oxygen consumption and ATP and restores NADH.

In APAP toxicity RNS/ROS is postulated to inhibits mitochondrial complex I

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to JAH [Grant R01-DK079008]. A part of the work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant R15 ES022781], National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant P20 GM109005] and Arkansas Science and Technology Authority [ASTA 15-B-19] to NAB and KJK.

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Hinson and James are part-owners of Acetaminophen Toxicity Diagnostics, LLC and have a patent pending for the development of a rapid assay for the measurement of 3-(cystein-S-yl)-acetaminophen (APAP-Cys) adducts in human samples.

Abbreviations

- APAP

Acetaminophen

- NAPQI

N-Acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine

- GSH

Reduced glutathione

- APAP-cys

3-(cystein-S-yl)-acetaminophen

- NO

Nitric Oxide

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2)

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1)

- GSNO

S-Nitrosoglutathione

- GSSG

Oxidized glutathione

- NANT

N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl) amino] pentyl]-N’-nitroguanidinetris (trifluoroacetate)

- MPT

Mitochondrial Permeability Transition

- LDH

Lactate Dehydrogenase

- OCR

Oxygen Consumption Rate

- 3-NT

3-Nitrotyrosine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.James LP, Mayeux PR, Hinson JA. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(12):1499–1506. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM, et al. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1401–1415. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlin DC, et al. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine: a cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(5):1327–1331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell JR, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. I. Role of drug metabolism. J. Pharmcol. Exp. Ther. 1973a;187:185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jollow DJ, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. VI. Metabolic disposition of toxic and nontoxic doses of acetaminophen. Pharmacology. 1974;12(4–5):251–271. doi: 10.1159/000136547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann KJ, et al. Identification of the major covalent adduct formed in vitro and in vivo between acetaminophen and mouse liver proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 1985;27(5):566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinson JA, et al. Nitrotyrosine-protein adducts in hepatic centrilobular areas following toxic doses of acetaminophen in mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11(6):604–607. doi: 10.1021/tx9800349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckman JS. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9(5):836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pryor WA, Squadrito GL. The chemistry of peroxynitrite: a product from the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(5 Pt 1):L699–L722. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L699. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiter CD, Teng RJ, Beckman JS. Superoxide reacts with nitric oxide to nitrate tyrosine at physiological pH via peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(42):32460–32466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910433199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sies H, et al. Glutathione peroxidase protects against peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations. A new function for selenoproteins as peroxynitrite reductase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(44):27812–27817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal R, MacMillan-Crow LA, Rafferty T, Saba H, Hinson JA. Acetaminophen-induced alterations in hepatic mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase MnSOD; SOD2) activity in mice. Experimental Biology 2010 Abstracts. 2010;C45:225. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelmegeed MA, et al. Robust protein nitration contributes to acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and acute liver injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;60:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kon K, et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;40(5):1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/hep.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid AB, et al. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial permeability transition in freshly isolated mouse hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(2):509–516. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne AM, Lemasters JJ, Nieminen AL. Contribution of increased mitochondrial free Ca2+ to the mitochondrial permeability transition induced by tert-butylhydroperoxide in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1999;29(5):1523–1531. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorov DB, et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1001–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke AS, MacMillan-Crow LA, Hinson JA. Reactive nitrogen species in acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial damage and toxicity in mouse hepatocytes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(7):1286–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx1001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stolz DB, et al. Peroxisomal localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36(1):81–93. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourdi M, et al. Role of IL-6 in an IL-10 and IL-4 double knockout mouse model uniquely susceptible to acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20(2):208–216. doi: 10.1021/tx060228l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michael SL, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase activity. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5(5):432–441. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinson JA, et al. Effect of inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Nitric Oxide. 2002;6(2):160–167. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schild L, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase controls enzyme activity pattern of mitochondria and lipid metabolism. FASEB J. 2006;20(1):145–147. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3898fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudin AP, et al. Characterization of superoxide-producing sites in isolated brain mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):4127–4135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson KM, et al. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):15038–15043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601945103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McQuade LE, Lippard SJ. Fluorescent probes to investigate nitric oxide and other reactive nitrogen species in biology (truncated form: fluorescent probes of reactive nitrogen species) Curr Opin Chem Biol. 14(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melnyk S, et al. A new HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of oxidized and reduced plasma aminothiols using coulometric electrochemical detection. J Nutr Biochem. 1999;10(8):490–497. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(99)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muldrew KL, et al. Determination of acetaminophen-protein adducts in mouse liver and serum and human serum after hepatotoxic doses of acetaminophen using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(4):446–451. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pathak R, et al. Characterization of transgenic Gfrp knock-in mice: implications for tetrahydrobiopterin in modulation of normal tissue radiation responses. Antioxid Redox Signal. 20(9):1436–1446. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reers M, et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential monitored by JC-1 dye. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:406–417. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hervera A, et al. The role of nitric oxide in the local antiallodynic and antihyperalgesic effects and expression of delta-opioid and cannabinoid-2 receptors during neuropathic pain in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(3):887–896. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hervera A, et al. Peripheral effects of morphine and expression of mu-opioid receptors in the dorsal root ganglia during neuropathic pain: nitric oxide signaling. Mol Pain. 2011;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaeschke H. Glutathione disulfide formation and oxidant stress during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice in vivo: the protective effect of allopurinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255(3):935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burwell LS, et al. Direct evidence for S-nitrosation of mitochondrial complex I. Biochem J. 2006;394(Pt 3):627–634. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitcheva V, Simeonova R, Mitcheva M. Experimental study on the effects of 7-nitroindazol, a selective inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), on some brain and hepatic biochemical parameters. FARMACIA. 2011;59(6):803–808. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas DD, et al. Protein nitration is mediated by heme and free metals through Fenton-type chemistry: an alternative to the NO/O2-reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(20):12691–12696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202312699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burcham PC, Harman AW. Effect of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity on hepatic mitochondrial and microsomal calcium contents in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 1988;44(1–2):91–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(88)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnelly PJ, Walker RM, Racz WJ. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration in vivo is an early event in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 1994;68:110–118. doi: 10.1007/s002040050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riobo NA, et al. Nitric oxide inhibits mitochondrial NADH: ubiquinone reductase activity through peroxynitrite formation. Biochem J. 2001;359(Pt 1):139–145. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan LJ. Pathogenesis of chronic hyperglycemia: from reductive stress to oxidative stress. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:137919. doi: 10.1155/2014/137919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pou S, et al. Generation of superoxide by purified brain nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(34):24173–24176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinson JA. Mechanisms of Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Disease. In: Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, editors. Drug Induced Liver Disease. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keszler A, Zhang Y, Hogg N. Reaction between nitric oxide, glutathione, and oxygen in the presence and absence of protein: How are S-nitrosothiols formed? Free Radic Biol Med. 48(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang AH, et al. Respiratory substrates regulate S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial proteins through a thiol-dependent pathway. Chem Res Toxicol. 2014;27(5):794–804. doi: 10.1021/tx400462r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beutner G, et al. Complexes between hexokinase, mitochondrial porin and adenylate translocator in brain: regulation of hexokinase, oxidative phosphorylation and permeability transition pore. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25(1):151–157. doi: 10.1042/bst0250151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boobis AR, et al. Evidence for a direct role of intracellular calcium in paracetamol toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39(8):1277–1281. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]