Abstract

Purpose

Estrogen (E2)-induced transcription requires coordinated recruitment of estrogen-receptor α (ER) and multiple factors at the promoter of activated genes. However, the precise mechanism by which this complex stimulates the RNA polymerase-II activity required to execute transcription is largely unresolved. We investigated the role of bromodomain (BRD) containing bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins, in E2-induced growth and gene activation.

Methods

JQ1, a specific BET protein inhibitor, was used to block BET protein function in two different ER-positive breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 and T47D). Real-time PCR and ChIP assays were used to measure RNA expression and to detect recruitment of various factors on the genes, respectively. Protein levels were measured by western blotting.

Results

JQ1 suppressed E2-induced growth and transcription in both MCF7 and T47D cells. The combination of E2 and JQ1 down-regulated the levels of ER protein in MCF7 cells but the loss of ER was not responsible for JQ1 mediated inhibition of E2 signaling. JQ1 did not disrupt E2-induced recruitment of ER and co-activator (SRC3) at the E2-responsive DNA elements. The E2-induced increase in histone acetylation was also not altered by JQ1. However, JQ1 blocked the E2-induced transition of RNA polymerase-II from initiation to elongation by stalling it at the promoter region of the responsive genes upstream of the transcription start site.

Conclusions

This study establishes BET proteins as the key mediators of E2-induced transcriptional activation. This adds another layer of complexity to the regulation of estrogen-induced gene activation that can potentially be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Estrogen, Transcription, BET proteins, JQ1, Estrogen receptor, RNA polymerase II

Introduction

Transcriptional activation of genes by estrogen (E2; 17β-estradiol) is a highly regulated process that requires the coordinated interaction of estrogen receptor α (ER) with estrogen responsive elements (EREs), followed by the binding of co-regulators and other chromatin modifying factors [1,2]. Co-regulators, which can be co-activators or co-repressors, can recruit other cofactors with diverse enzymatic activities required for modulating the transcriptional process [3]. E2-liganded ER and the p160 family of co-activators (SRC1, SRC2, SRC3) form a dynamic transcription activation complex [1,4] that interacts with CBP and p300 co-activators [5] possessing intrinsic histone acetyl-transferase (HAT) activity [6-8]. Addition of acetyl groups specifically occurs at the lysine residues of the N-terminal histone proteins by HAT activity, resulting in enhanced accessibility of the chromatin to the transcriptional machinery [9]. These chromatin alterations eventually lead to the synthesis of the RNA of E2 responsive genes by RNA polymerase II (RNAP) [4,10]. However, the components and the events responsible for “reading” the hyper-acetylated histone chromatin that are necessary to integrate RNAP activation in the context of E2-regulated genes, are poorly understood.

Studies have established that dual bromodomain containing bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins, which include BRD2, BRD3 and BRD4, play important roles in stimulation of transcription by RNAP [11-13]. The bromodomains of the BET proteins bind to acetylated lysines of the histones, whereas the extra-terminal (ET) domain of the protein can interact independently with multiple other proteins [14]. BRD4 interacts with the positive transcription elongation factor b (PTEFb) [11], which is responsible for the transcriptional elongation by RNAP [15]. BRD2 and BRD3 also bind to hyper-acetylated histone 3 (H3) and histone 4 (H4) and permit transcriptional elongation by RNAP [13]. Interest in the BET proteins has increased recently due to the discovery of the potential therapeutic selective inhibitor of BET bromodomains, JQ1, which can block the interface of the bromodomain responsible for recognizing the acetylated lysines in histones [16]. JQ1 has been used extensively as a chemical tool to delineate the effects of BET proteins in various disease specific studies [17,18,16,19-22].

However, the roles of BET proteins in E2-induced transcription in the ER positive breast cancers have not been examined before. We studied the effect of BET protein inhibition using JQ1 on the growth and the transcriptional regulation of estrogen (E2)-stimulated genes in two distinct ER positive breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 and T47D). These cells regulate the ER differently [23]. By studying three established and well characterized E2-regulated genes namely, pS2 (TFF1) [1,2], GREB1 [24], and XBP1 [25,26], this study demonstrates the key role of the BET proteins in E2-induced transcription by ER.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

Cell culture media were purchased from Invitrogen Inc. (Grand Island, NY) and fetal calf serum (FCS) was obtained from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT). The ERα+ breast cancer cells MCF-7:WS8 (mentioned as MCF7 hereafter) were derived from MCF7 cells [27] obtained from Dr. Dean Edwards, San Antonio, Texas and T47D A:18 cells (mentioned as T47D hereafter) were derived from T47D cells as reported previously [28]. The cells were maintained in phenol red-containing RPMI media supplemented with 10% FCS. Three to four days prior to treatment the cells were cultivated in phenol red-free media containing 10% charcoal dextran treated FCS. BET protein inhibitor, JQ1 (cat # 4499) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience, (Bristol, UK) and the inactive JQ1 stereo-isomer (cat # A8181) was purchased from Apex Bio Technologies (Boston, MA). All the experiments were performed at least three times, in triplicate to confirm the results.

Cell growth assay

Cell growth assays were performed by measuring the total DNA per well in 24 well plates. Eight thousand cells were plated per well and treatment with indicated concentrations of compounds was started after 24 hours, in triplicates. Media with specific treatments were changed every 48 hours. Cells were harvested after six days of treatment in hypotonic buffer solution followed by sonication. Total DNA was measured using a fluorescent dye (Hoechst 33258) in the DNA quantitation kit (Cat # 170-2480; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA isolation and real time PCR

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) were used to isolate total RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was performed as previously described [29]. Briefly, cDNA was generated from 1 ug of total RNA in a total volume of 20 μl using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Subsequently, the cDNA was diluted to 500 μl and RT-PCR was performed using ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each well contained 10 μl SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 125 nM each of forward and reverse primers and 5 μl of diluted cDNA in 20 μl final volume. The change in expression of transcripts was determined as described previously and used the ribosomal protein 36B4 mRNA as the internal control [29]. Details of the primers used for TFF1, GREB1, XBP1, ER alpha and 36B4 genes can be found in supplementary table 1.

Western blotting

RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and phosphatase inhibitors I and II (EMD Chemicals Inc. San Diego, CA) was used to extract whole cell protein lysates. 15-20 μg of total protein was run on the gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were subsequently blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in tris-buffered saline and probed with primary and secondary antibodies. Specific bands were visualized using west-pico chemi-luminescence (Thermo-Fisher, Rockford, IL, USA). The antibodies used were: ER alpha (# sc-544; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), and beta actin (#A5441; Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed as described previously [29]. Briefly, cells were treated with the indicated treatments for 45 minutes and cross-linked using 1.25% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and subsequently cross-linking was stopped with 2 M glycine. Nuclei were isolated from cells that were re-suspended in SDS-lysis buffer followed by sonication and centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were diluted 1:10 with ChIP dilution buffer. Pre-clearing of the samples were performed by normal rabbit IgG and protein A magnetic beads (Upstate cell signaling solutions, Temecula, CA) followed by over-night incubation using specific antibodies against ER alpha(1:1 ratio of sc-7207 and sc-543; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), SRC3 (sc-13066; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), acetylated histone 4 (06-866; Upstate cell signaling solutions, Temecula, CA) and RNA polymerase II (sc-56767; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). The immuno-complexes were pulled down using protein A magnetic beads (Upstate cell signaling solutions, Temecula, CA). Beads bound to immuno-complexes were thereafter washed and precipitates were extracted twice using freshly made 1% SDS and 0.1M NaHCO3 followed by de-crosslinking. DNA fragments were purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RT-PCR was performed using 2 μL isolated DNA, using loci specific primers. Details of the primer sequences for the promoters and gene coding region can be found in the supplementary table 2. The data are represented as fold enrichment over normal IgG pull down for each treatment sample after calculating the percent input. The “traveling ratio” of the RNAP, which is a measurement of its elongation function [30], was calculated as the ratio of fold enrichment of RNAP at the promoter and the coding region for each gene.

Statistics

Statistical significance of our data was calculated using the paired Student's “t”-test wherever relevant. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

JQ1 blocks E2-induced cell proliferation and ER mediated gene activation in MCF7 and T47D breast cancer cells

Most estrogen receptor positive breast cancers depend upon estrogen for cell proliferation and growth. We examined the dose dependent effect of the BET protein inhibitor JQ1, on E2-induced growth of MCF7 and T47D breast cancer cells. JQ1 inhibited E2-induced growth of both the breast cancer cell lines in a concentration dependent manner (figure 1A and 1B). In both cell lines, 500 nM JQ1 was sufficient to block the E2-induced growth completely over a six day period. This growth inhibition was due to a reduction in proportion of the cells in “S” phase cells by JQ1 as evidenced by the cell cycle analysis (supplementary figure S1A and S1B). Basal growth of the cells in the absence of E2 was also moderately inhibited over this time period. Next, we examined the inhibitory effect of JQ1 on ER mediated transcriptional activation of representative E2-responsive genes, TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1. Expression of all these genes was up-regulated by 1 nM E2 after 6 hrs of treatment in both MCF7 and T47D cells, an effect that was almost completely inhibited by JQ1 (figures 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F, 1G, 1H). A well-defined dose-dependent inhibitory effect of JQ1 was not evident; even the lowest concentration of JQ1 (125nM) blocked E2-induced gene activation and the higher concentrations of JQ1 did not enhance this effect significantly.

Figure 1. JQ1 inhibits estrogen (E2)-induced growth and transcription of E2 responsive genes in MCF7 and T47D cells.

Total DNA was measured to assess the growth of MCF7 and T47D cells after 6 days of treatment with E2 alone or in combination with increasing concentrations of JQ1 in (A) MCF7 and (B) T47D cells. Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (C, D and E respectively) were assessed in MCF7 cells using real time PCR after 6 hours of treatment with Vehicle (Veh) or E2 or indicated concentration of JQ1 in combination with E2. Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (F, G and H respectively) were assessed in T47D cells using real time PCR after 6 hours of treatment with Vehicle (Veh), E2, JQ1 or indicated concentration of JQ1 in combination with E2. (* p<.05 versus E2 treatment alone)

Inhibition of E2-induced gene activation by JQ1 is enantiomer specific and is rapidly reversible

To investigate specificity of JQ1 mediated inhibition we used the inactive enantiomer of JQ1 ((−)-JQ1; figure 2A) that is unable to bind the acetyl-lysine binding pocket of the bromodomain [16]. (−)-JQ1 (250 nM) failed to inhibit the E2-induced gene activation of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 in both MCF7 and T47D cells (figure 2C, through 2H), when compared with the 250 nM JQ1 treatment in combination with E2. E2-induced growth over a period of six days, of both MCF7 and T47D cells also was not inhibited by (−)-JQ1 (figure 2B) unlike JQ1. To further examine if there was an extended inhibitory effect of JQ1 on E2-regulated genes, even after the withdrawal of JQ1, we treated the MCF7 cells with E2 (1 nM) +JQ1 (250 nM) for 2 hrs and then removed JQ1 from the media and maintained the cells under E2 (1 nM) treatment for 30, 60 and 120 minutes. As expected, two hours of JQ1 treatment (250 nM) in combination with E2 almost completely blocked the E2 activation of the TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 genes (figures 3A, 3B and 3C). However, withdrawal of JQ1 from the treatment rapidly (within 120 minutes) restored the hormone mediated activation of all the genes to a level comparable to E2 treatment alone after 2 hours (figures 3A, 3B and 3C). Interestingly, the kinetics of the activation of these genes after JQ1 withdrawal (figures 3A, 3B and 3C) and with E2 treatment alone (figures 4E, 4F and 4G) were the same. Thus, JQ1 mediated inhibition is not only reversible but its constant presence is necessary for its effectiveness.

Figure 2. JQ1 mediated inhibition of estrogen (E2)-induced growth and transcription in MCF7 and T47D cells is stereo-isomer specific.

(A) Chemical structures of active (+)-JQ1 and inactive (−)-JQ1 compound. (B) Total DNA was measured to assess the growth of MCF7 and T47D cells after 6 days of treatment with vehicle or E2 alone or in combination with 250 nM of active (+)-JQ1 or inactive (−)-JQ1 compound in MCF7 and T47D cells. Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (C, D and E respectively) were assessed in MCF7 cells using real time PCR after 6 hours of treatment with Vehicle (Veh), E2 or in combination with 250nM of active (+)-JQ1 or inactive (−)-JQ1 compound. Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (F, G and H respectively) were assessed in T47D cells using real time PCR after 6 hours of treatment with Vehicle (Veh), E2, or in combination with 250 nM of active (+)-JQ1 or inactive (−)-JQ1 compound.

Figure 3. Rapid reversal of JQ1 mediated inhibition of estrogen (E2)-induced transcription in MCF7 cells after JQ1 withdrawal.

Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (A, B and C respectively) were assessed in MCF7 cells using real time PCR. Cells were treated for 2 hours with Vehicle (Veh), E2, JQ1 or in combination with 250 nM of active (+)-JQ1. To assess the effect of JQ1 withdrawal JQ1+E2 containing media was replaced after two hours with E2 only media and harvested at 30, 60 and 120 minutes after the media change. (* p<.05 versus E2 + JQ1 treatment)

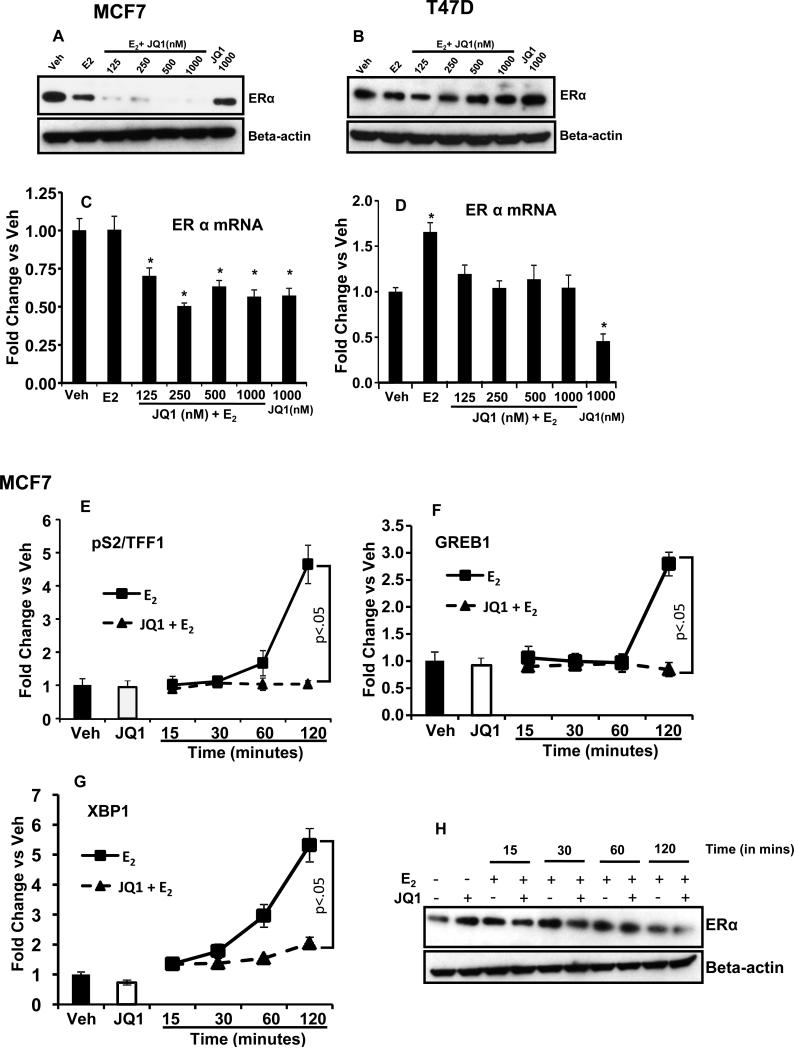

Figure 4. Differential regulation of ER alpha by JQ1+E2 in MCF7 and T47D cells.

Levels of ER alpha protein was measured by western blot after 6 hours treatment with vehicle (Veh), E2 or a combination of indicated concentration of JQ1plus E2 (10−9M) in (A) MCF7 and (B) T47D cells. The mRNA levels of ER alpha were assessed by quantitative real time PCR in (C) MCF7 and (D) T47 D cells in identically treated cells as for western blot. (* p<.05 versus vehicle treatment) Levels of TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 mRNA (E, F and G respectively) were assessed in MCF7 cells using real time PCR. Cells were treated for indicated time period (15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes) with E2 alone or in combination with (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) . The cells treated with vehicle or (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) alone were harvested after 120 minutes. (H) Level of ER alpha protein was measured by western blot in MCF7 cells treated for indicated time period (15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes) with E2 alone or in combination with (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) . The cells treated with vehicle or (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) alone were harvested after 120 minutes.

JQ1 and E2 combination drastically reduces ER levels in MCF7 cells but is not responsible for the inhibitory effect of JQ1

To examine the effect of JQ1 plus E2 combination treatment on the expression of ER, we determined the levels of ER protein and mRNA in E2+JQ1 treated MCF7 and T47D cells. Different regulation of ER protein expression was observed for the two cell lines as T47D cells did not show any remarkable change in ER protein levels after E2+JQ1 treatment for 6 hrs (figure 4B). In contrast, MCF7 cells exhibited drastic reduction of ER protein after 6 hrs of E2+JQ1 treatment (figure 4A), whereas the reduction was less evident in cells treated with E2 or JQ1 alone. Opposing regulation of ER mRNA in MCF7 and T47D cells was observed; JQ1 and E2 combination treatment suppressed the levels of ER mRNA in MCF7 (figure 4C) but not in T47D cells (figure 4D). However, treatment with JQ1 alone reduced the ER mRNA levels by 40% to 50% in both the cell lines (figures 4C and 4D). Conversely, E2 alone increased ER mRNA expression in T47D cells but no change was observed in MCF7 cells. Since ER protein levels were significantly reduced in MCF7 cells treated with JQ1 plus E2; we investigated if these changes in ER were responsible for the impairment of the E2 gene regulation. We first focused on the early time points after hormone treatment and found that E2 up-regulated TFF1 and XBP1 within 60 minutes and GREB1 within 120 minutes of treatment (figures 4E, 4F and 4G). JQ1 completely blocked this up-regulation at each time point, whereas expression of ER protein did not alter significantly during this time period (figure 4H) except for the 120 min treatment with JQ1 + E2. To determine further if exogenous ER expression can reverse the JQ1 mediated inhibition of E2-regulated genes, we over-expressed ER in MCF7 cells using a tet-off adenovirus system [31] and treated the cells with vehicle, E2, JQ1 and E2+JQ1 for 18 hrs. Exogenous ER expression (supplementary figure S2A) was unable to rescue the JQ1-mediated inhibition of E2 regulated genes (supplementary figure S2B, S2C and S2D), further confirming that the inhibitory effect of JQ1 was not dependent on the reduced ER expression in MCF7 cells.

JQ1 treatment does not disrupt E2-induced recruitment of ER, SRC3 or histone acetylation status at the promoters of genes

To understand the mechanism by which JQ1 inhibited the E2- induced transcription of responsive genes, we examined if JQ1 disrupted the recruitment of ER and/or the co-activator SRC3 at the promoters of the responsive genes after E2 treatment. Recruitment of these factors at the promoter regions of TFF1, GREB1 or XBP1 genes harboring EREs (Figure 5A, 5E, and 5I) was investigated using ChIP assays in MCF7 cells. These ERE sites have been well characterized and recruitment of ER and other factors at these sites have been associated with E2-induced transcription of these genes [25,26,32,24,33,1]. Recruitment of ER and SCR3 at these sites was evaluated after 45 minutes of treatment with vehicle, E2, JQ1 and E2+JQ1. As expected, E2 treatment induced recruitment of both ER and SRC3 at the promoter EREs of each of the TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 genes (Figure 5B, 5C, 5F, 5G, 5J, and 5K). This recruitment was associated with E2-induced hyper-acetylation of histone H4 (Figure 5D, 5H and 5L). Treatment with JQ1 alone had no effect on these parameters. Interestingly, JQ1+E2 also did not affect the E2-induced recruitment of ER and SRC3 at the TFF1 and GREB1 promoters. In the case of XBP1, a slight suppression in recruitment of ER and SRC3 was observed in the presence of JQ1. Modest reduction in E2-induced hyper-acetylation of H4 was observed by JQ1 in the TFF1 and GREB1 genes but not with XBP1 (Figure 5D, 5H, and 5L).

Figure 5. Effect of JQ1 on E2-induced recruitment of ER, SRC3 and hyper-acetylation of histone H4 protein at the promoters of E2-responsive genes in MCF7 cells.

ChIP assay followed by real-time PCR was used to assess the recruitment of ER alpha, SRC3 and histone acetylation status for the ERE promoter region of (A) TFF1 (E) GREB1 and ERE enhancer region of (I) XBP1 gene. The black bars below the ERE regions of the schematically represented genes depicts region amplified by real-time PCR. Fold enrichment versus IgG (normal rabbit) was calculated for ER alpha, SRC3 and acetylated H4 for TFF1 (B, C, and D respectively), GREB1 (F, G, and H respectively) and XBP1 (J, K, and L respectively) after 45 minutes of treatment with vehicle (0.1% ethanol), E2 (10−9M), (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) or JQ1+E2. (* p<.05 versus E2 treatment alone)

JQ1 blocks E2-induced RNA polymerase II (RNAP) advancement from the promoters to the coding region of the gene

Since E2-induced recruitment of RNAP and its elongation activity at the promoters of the responsive genes is necessary to stimulate the transcription process, we measured enrichment of the RNAP by ChIP assay followed by loci-specific qRT-PCR. To evaluate its density at the proximal promoter we designed primers for the loci that were upstream of the transcription start site. For TFF1 and GREB1, these were the same regions that contained the ERE. For XBP1, we used primers for 300bp upstream region, which recruits higher level of RNAP than the enhancer region (−13kb) containing the ERE [26]. To assess the elongation activity of the RNAP enzyme, we evaluated its enrichment (density) at the coding region of the gene body of all the three genes. The density of RNAP on the gene body positively correlates with its transcriptional elongation activity in MCF7 cells [34]. Therefore, separate primers were used to assess the RNAP recruitment in the coding region of each gene as outlined in the Figure 6A, 6E and 6I. The results revealed that JQ1 marginally (19%-35%) suppressed E2-induced RNAP recruitment at the proximal promoter of all the genes tested (Figure 6B, 6F and 6J). In contrast, RNAP recruitment was notably lower (~80%) in the coding region of the gene body for TFF1 and GREB1 in presence of JQ1 and E2. For XBP1, we observed a 45% reduction in RNAP recruitment in the gene body (Figure 6C, 6G and 6K) compared with E2 only. A measure of transitional activity from initiation to elongation of RNAP can be represented by the “traveling ratio”, which depicts the ratio of RNAP association with the promoter to the coding region [30]. Evaluation of the traveling ratio showed that E2 treatment was associated with a substantial reduction in the traveling ratio for TFF1, GREB1 and XBP1 (Figure 6D, 6H and 6L), indicating proficient transcription elongation activity. The reduction in traveling ratio by E2 was fully reversed by JQ1 treatment for TFF1 and GREB1, but only slightly for XBP1 gene (Figure 6D, 6H and 6L). Interestingly, XBP1 also showed high recruitment of RNAP at the promoter and in the coding region even in the absence of E2, which was not reversed by JQ1 alone (Figure 6J and 6K). In fact at the promoter region of XBP1 gene, JQ1 alone enhanced the recruitment of the RNAP as compared with vehicle (Figure 6J).

Figure 6. Effect of JQ1 on E2-induced recruitment of RNA polymerase-II enzyme (RNAP) at the proximal promoters and gene coding region of E2-responsive genes in MCF7 cells.

ChIP assay followed by real-time PCR was performed to assess the recruitment of RNAP at the promoter and gene coding region of (A) TFF1 (E) GREB1 and (I) XBP1 gene. The black bars below the schematically represented genes depicts region amplified by real-time PCR. Fold enrichment versus IgG (normal rabbit) was calculated for RNAP at the promoter and gene coding region TFF1 (B and C respectively), GREB1 (F and G respectively) and XBP1 (J and K respectively) after 45 minutes of treatment with vehicle (0.1% ethanol), E2 (10−9M), (+)-JQ1 (250nm) or JQ1+E2. The travel ratio of RNAP for (D) TFF1, (H) GREB1 and (L) XBP1 was calculated as mentioned in the materials and method section after 45 minutes of treatment with vehicle (0.1% ethanol), E2 (10−9M), (+)-JQ1 (250 nM) or JQ1+E2. The % numbers in B, C, F, G, J and K graphs correspond to percent decrease in RNAP enrichment in E2+JQ1treated cells compared to E2 treatment alone. (* p<.05 versus E2 treatment alone)

Discussion

Histone acetylation at the promoters of E2 induced genes is one of the key chromatin modifications required for the activation of transcription [8,10]. Based on our data we postulate (Figure 7) that the BET proteins, which can recognize the acetylated histones in the chromatin [35,36] and allow transcriptional elongation by RNAP [12,37], are essential for the E2- induced gene activation in ER positive breast cancer cells. While this manuscript was being prepared a similar study was published [38] that reported BRD4 dependent elongation activity of RNAP in estrogen-induced gene activation. Our data is consistent with the findings of the study [38], and in addition, we show that BRD2 is also recruited at the promoters of estrogen regulated genes (supplementary figure 5). These observations underscore the critical role of multiple BET proteins in estrogen regulation of genes in breast cancers and other estrogen target tissues.

Figure 7.

Schematic presentation of the proposed model for the role of BET proteins in estrogen induced transcription

JQ1, a small molecule that mimics acetylated lysine, can selectively block the bromodomains of the BET proteins, (BRD2, BRD3 and BRD4) [16]. Expression of each BET protein was confirmed in MCF7 and T47D cells (supplementary figure 4). Using JQ1 as a tool to block BET protein function we demonstrate complete inhibition of E2- induced transcription and growth (figure 1). The stereo-isomer of JQ1, ((−) JQ1), which is unable to bind to the bromodomains [16], failed to inhibit E2 induced gene activation as well as growth (figure 2). Thus, recognition of the histone acetylated lysines by the dual bromodomains of BET proteins is a key event in the E2- regulation of the genes. Furthermore, our results indicated (supplementary figure 3) a direct inhibitory role of JQ1 since de novo protein synthesis was not a pre-requisite for the inhibitory effect of JQ1 on the estrogen-regulated genes.

Our results (figure 4) on the effect of JQ1 on ER protein expression revealed opposing regulation in MCF7 and T47D cells. Differential E2 regulation of ER in these cells has been previously reported from our laboratory [23], where ER mRNA is down-regulated by E2 in MCF7 cells but up-regulated in T47D cells [23]. In addition, ER protein is known to undergo ubiquitin mediated degradation by E2 in MCF7 and other cells [39-41]. In this study we provide evidence that BET proteins are involved in maintaining the basal ER mRNA levels in both MCF7 and T47D cells as JQ1 treatment down-regulated the ER mRNA in both the cell lines (figure 4C and D). However, short term (6 hours) combination treatment of E2 and JQ1 reduced the ER protein levels in MCF7 cells only (figure 4A and B). This outcome was most likely due to the additive effect of reduced mRNA by JQ1 and E2- mediated ER protein degradation. While the loss of ER in MCF7 cells was not responsible for the inhibitory effects of JQ1 (figure 4E-G and supplementary figure 2), the contrasting regulation of ER protein in MCF7 and T47D cells in presence of JQ1+E2 indicates alternative mechanisms for the maintenance of ER protein levels in diverse breast cancer cells.

Since JQ1 did not disrupt either the E2 -induced recruitment of ER and SRC3 at the promoters or the histone hyper-acetylation in the region (Figure 5), BET protein function is not clearly essential for either the binding of ER at the ERE or formation of the initial transcription complex at the promoters, including the recruitment of RNAP (Figure 6B, F and J). In contrast, BET protein function was indispensable for the activation and advancement of the RNAP onto the coding region of the E2-regulated genes as JQ1 treatment, which blocked recruitment of BET proteins (supplementary figure 5), and stalled RNAP at the promoters upstream of the transcription start sites (Figure 6C, G and K). This establishes BET proteins as an essential component for integrating the E2-ER/co-activator complex with RNAP activation.

Phosphorylation of serine-2 at the carboxy terminal domain (CTD) of RNAP by positive transcription elongation factor b (PTEFb), a heterodimer of CDK9 and cyclin T1, precedes transcription elongation function [42,43]. BET proteins, particularly BRD4, are known to interact with PTEFb [37,11], and positively influence transcription by RNAP. Besides BRD4 other BET protein family members, BRD2 and BRD3, have also been shown to couple histone acetylation with transcription [13]. Interestingly, BRD4 protein has also been suggested to activate RNAP independent of PTEFb [44,45]. Since JQ1 can bind to all the BET protein family members [16], more than one member may play an important role in the E2-mediated transcriptional elongation by RNAP. The transcription elongation is characterized by CDK9 mediated serine-2 phosphorylation of CTD of RNAP [46,47,15] and increased density of RNAP into the coding region of the gene body [34]. Recruitment of CDK9 and subsequent activation of RNAP of the estrogen regulated genes (including TFF1 and GREB1) [48] in MCF7 cells have been previously reported [48]. The observations that BET proteins can interact with CDK9 [37,11], coupled with our data strongly suggest that BET proteins are responsible for engaging CDK9 at the promoters of the E2 responsive genes. Recent studies have underscored the importance of BET proteins; their association with CDK9 have also been reported in the context of interferon stimulated genes [49]. These observations attain clinical significance because we recently showed that constitutive high cMYC transcription mediated by CDK9 is a critical determinant of endocrine-therapy resistance breast cancers [50]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that inhibition of BET proteins may prove to be clinically beneficial for endocrine therapy refractory breast cancers. Indeed, JQ1 has been successfully used in pre-clinical studies in vivo [18,16] including for breast cancers driven by cMYC [51].

Consistent with the functional role of BET proteins, our results (Figure 6D, H and L) demonstrate that the traveling ratio of RNAP (a measure of the rate of transition from initiation to elongation) at the promoters of E2-induced genes was reversed in the presence of JQ1. The E2-induced reduction in the traveling ratio (Figure 6D, H and L) indicated a high density of RNAP at the coding region, which was consistent with high transcription activity. This effect was completely reversed to the vehicle treated levels by JQ1 treatment for TFF1 and GREB1 (Figure 6D, and H), suggesting stalling of the RNAP at the promoter region. For XBP1 (Figure 6L), very little change was observed in the traveling ratio in presence of JQ1+E2 versus E2 alone, despite ~40% decrease in RNAP association in the coding region in the presence of JQ1+E2. XBP1 gene expression may have an E2 and BET protein independent component, as evident from the high RNAP recruitment at the promoter and coding region even in the vehicle treated cells. Moreover, treatment with JQ1 alone was unable to reverse this RNAP recruitment (figure 6J and K). This emphasizes the possibility that not all E2-induced genes may be exclusively regulated in a BET protein dependent manner and other mechanisms may also play important roles. Nonetheless, JQ1 blocked the E2-induced growth of breast cancer cells (figure 1A and B) by restricting the cells in the ‘G1’ phase of the cell cycle (supplementary figure 1A and B), suggesting BET proteins as a potential therapeutic target.

The E2 liganded ER engages in a cyclic recruitment process of the receptor and other factors including the RNAP enzyme at the responsive promoters [1,4]. It is important to note that BET protein inhibition had a marginal but consistent reduction in the recruitment of RNAP at the promoter region (Figure 6A, F and J) that was also reported by another study evaluating interferon stimulated genes [49]. This effect may be due to disruption of the dynamics of the cyclic events or / and to a failure of re-initiation of transcription by RNAP. Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of BET proteins on the cyclical recruitment of the liganded ER and other factors. Nevertheless, the results indicate that the role of BET proteins is largely restricted to regulating advancement of the RNAP and the transcription elongation process without interfering with the initial recruitment of ER and other necessary factors.

In conclusion, our data revealed BET proteins as a factor integrating the ER transcriptional complex with the RNAP activation of E2 regulated genes. This study, along with a recent report [38], enriches our understanding of hormone induced ER-mediated transcriptional regulation and defines BET proteins as a critical regulator of transcriptional activation of E2-regulated genes in ER positive breast cancers. Our study further provides opportunities to explore new therapeutic targets for breast cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Defense Breast Program under Award number W81XWH-06-1-0590 Center of Excellence (VCJ), and in part by Dean's Pilot Project Award 2014 (SS), Public Health Service Awards U54-CA149147 (RC) and the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Core Grant NIH P30 CA051008. The views and opinions of the author(s) do not reflect those of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, Gannon F. Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell. 2003;115(6):751–763. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00934-6. doi:S0092867403009346 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103(6):843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. doi:S0092-8674(00)00188-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulynko YA, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coactivators: structural and functional biochemistry. Biochemistry. 2011;50(3):313–328. doi: 10.1021/bi101762x. doi:10.1021/bi101762x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metivier R, Reid G, Gannon F. Transcription in four dimensions: nuclear receptor- directed initiation of gene expression. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(2):161–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400626. doi:7400626 [pii] 101038/sj.embor.7400626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanstein B, Eckner R, DiRenzo J, Halachmi S, Liu H, Searcy B, Kurokawa R, Brown M. p300 is a component of an estrogen receptor coactivator complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(21):11540–11545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demarest SJ, Martinez-Yamout M, Chung J, Chen H, Xu W, Dyson HJ, Evans RM, Wright PE. Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature. 2002;415(6871):549–553. doi: 10.1038/415549a. doi:10.1038/415549a 415549a [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin SC, Heyman RA, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85(3):403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. doi:S0092-8674(00)81118-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MY, Hsiao SJ, Kraus WL. A role for coactivators and histone acetylation in estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transcription initiation. EMBO J. 2001;20(21):6084–6094. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6084. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.21.6084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128(4):707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. doi:S0092-8674(07)00109-2 [pii] 101016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kininis M, Chen BS, Diehl AG, Isaacs GD, Zhang T, Siepel AC, Clark AG, Kraus WL. Genomic analyses of transcription factor binding, histone acetylation, and gene expression reveal mechanistically distinct classes of estrogen-regulated promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(14):5090–5104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00083-07. doi:MCB.00083-07 [pii] 101128/MCB.00083-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, Yik JH, Chen R, He N, Jang MK, Ozato K, Zhou Q. Recruitment of P-TEFb for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by the bromodomain protein Brd4. Mol Cell. 2005;19(4):535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.029. doi:S1097-2765(05)01431-0 [pii] 101016/j.molcel.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Prakash C, Sum C, Gong Y, Li Y, Kwok JJ, Thiessen N, Pettersson S, Jones SJ, Knapp S, Yang H, Chin KC. Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) regulates RNA polymerase II serine. 2 phosphorylation in human CD4+ T cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):43137–43155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413047. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.413047 M112.413047 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeRoy G, Rickards B, Flint SJ. The double bromodomain proteins Brd2 and Brd3 couple histone acetylation to transcription. Mol Cell. 2008;30(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.018. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.018 S1097-2765(08)00157-3 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belkina AC, Denis GV. BET domain co-regulators in obesity, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(7):465–477. doi: 10.1038/nrc3256. doi:10.1038/nrc3256 nrc3256 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterlin BM, Price DH. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol Cell. 2006;23(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. doi:S1097-2765(06)00429-1 [pii] 101016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. doi:10.1038/nature09504 nature09504 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand P, Brown JD, Lin CY, Qi J, Zhang R, Artero PC, Alaiti MA, Bullard J, Alazem K, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Lemieux M, Plutzky J, Bradner JE, Haldar SM. BET bromodomains mediate transcriptional pause release in heart failure. Cell. 2013;154(3):569–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.013 S0092-8674(13)00884-2 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, Chesi M, Schinzel AC, McKeown MR, Heffernan TP, Vakoc CR, Bergsagel PL, Ghobrial IM, Richardson PG, Young RA, Hahn WC, Anderson KC, Kung AL, Bradner JE, Mitsiades CS. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146(6):904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017S0092-8674(11)00943-3 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel RR, Sengupta S, Kim HR, Klein-Szanto AJ, Pyle JR, Zhu F, Li T, Ross EA, Oseni S, Fargnoli J, Jordan VC. Experimental treatment of oestrogen receptor (ER) positive breast cancer with tamoxifen and brivanib alaninate, a VEGFR-2/FGFR-1 kinase inhibitor: a potential clinical application of angiogenesis inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(9):1537–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.018. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.018 S0959-8049(10)00145-0 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott CJ, Kopp N, Bird L, Paranal RM, Qi J, Bowman T, Rodig SJ, Kung AL, Bradner JE, Weinstock DM. BET bromodomain inhibition targets both c-Myc and IL7R in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(14):2843–2852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-413021. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-02-413021blood-2012-02-413021 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee C, Archin N, Michaels D, Belkina AC, Denis GV, Bradner J, Sebastiani P, Margolis DM, Montano M. BET bromodomain inhibition as a novel strategy for reactivation of HIV-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92(6):1147–1154. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312165. doi:10.1189/jlb.0312165 jlb.0312165 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trabucco SE, Gerstein RM, Evens AM, Bradner JE, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Zhang H. Inhibition of bromodomain proteins for the treatment of human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3346. doi:clincanres.3346.2013 [pii] 1078-0432.CCR-13-3346 [pii] 101158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pink JJ, Jordan VC. Models of estrogen receptor regulation by estrogens and antiestrogens in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996;56(10):2321–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Nawaz Z, Slingerland JM. Long-range activation of GREB1 by estrogen receptor via three distal consensus estrogen-responsive elements in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(11):2651–2662. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0082. doi:me.2007-0082 [pii] 101210/me.2007-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell. 2005;122(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.008. doi:S0092-8674(05)00453-8 [pii] 101016/j.cell.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta S, Sharma CG, Jordan VC. Estrogen regulation of X-box binding protein-1 and its role in estrogen induced growth of breast and endometrial cancer cells. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2010;2(2):235–243. doi: 10.1515/HMBCI.2010.025. doi:10.1515/HMBCI.2010.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang SY, Wolf DM, Yingling JM, Chang C, Jordan VC. An estrogen receptor positive MCF-7 clone that is resistant to antiestrogens and estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;90(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90104-e. doi:0303-7207(92)90104-E [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy CS, Pink JJ, Jordan VC. Characterization of a receptor-negative, hormone-nonresponsive clone derived from a T47D human breast cancer cell line kept under estrogen-free conditions. Cancer Res. 1990;50(22):7285–7292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta S, Obiorah I, Maximov P, Curpan R, Jordan VC. Molecular mechanism of action of bisphenol and bisphenol A mediated by oestrogen receptor alpha in growth and apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169(1):167–178. doi: 10.1111/bph.12122. doi:10.1111/bph.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wade JT, Struhl K. The transition from transcriptional initiation to elongation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.008 S0959-437X(08)00003-8 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng J, Jordan VC. Expression of estrogen receptor alpha with a Tet-off adenoviral system induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in SKBr3 breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2010;36(2):451–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fullwood MJ, Liu MH, Pan YF, Liu J, Xu H, Mohamed YB, Orlov YL, Velkov S, Ho A, Mei PH, Chew EG, Huang PY, Welboren WJ, Han Y, Ooi HS, Ariyaratne PN, Vega VB, Luo Y, Tan PY, Choy PY, Wansa KD, Zhao B, Lim KS, Leow SC, Yow JS, Joseph R, Li H, Desai KV, Thomsen JS, Lee YK, Karuturi RK, Herve T, Bourque G, Stunnenberg HG, Ruan X, Cacheux- Rataboul V, Sung WK, Liu ET, Wei CL, Cheung E, Ruan Y. An oestrogen-receptor- alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462(7269):58–64. doi: 10.1038/nature08497. doi:10.1038/nature08497 nature08497 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zwart W, Theodorou V, Kok M, Canisius S, Linn S, Carroll JS. Oestrogen receptor- co-factor-chromatin specificity in the transcriptional regulation of breast cancer. EMBO J. 2011;30(23):4764–4776. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.368. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.368 emboj2011368 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danko CG, Hah N, Luo X, Martins AL, Core L, Lis JT, Siepel A, Kraus WL. Signaling pathways differentially affect RNA polymerase II initiation, pausing, and elongation rate in cells. Mol Cell. 2013;50(2):212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.015. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.015 S1097-2765(13)00171-8 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dey A, Chitsaz F, Abbasi A, Misteli T, Ozato K. The double bromodomain protein Brd4 binds to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(15):8758–8763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1433065100. doi:10.1073/pnas.1433065100 1433065100 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vollmuth F, Blankenfeldt W, Geyer M. Structures of the dual bromodomains of the P TEFb-activating protein Brd4 at atomic resolution. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(52):36547–36556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033712. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.033712 M109.033712 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang MK, Mochizuki K, Zhou M, Jeong HS, Brady JN, Ozato K. The bromodomain protein Brd4 is a positive regulatory component of P-TEFb and stimulates RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. Mol Cell. 2005;19(4):523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.027. doi:S1097-2765(05)01432-2 [pii] 101016/j.molcel.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagarajan S, Hossan T, Alawi M, Najafova Z, Indenbirken D, Bedi U, Taipaleenmaki H, Ben-Batalla I, Scheller M, Loges S, Knapp S, Hesse E, Chiang CM, Grundhoff A, Johnsen SA. Bromodomain protein BRD4 is required for estrogen receptor-dependent enhancer activation and gene transcription. Cell Rep. 2014;8(2):460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.016. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.016 S2211-1247(14)00484-7 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alarid ET, Bakopoulos N, Solodin N. Proteasome-mediated proteolysis of estrogen receptor: a novel component in autologous down-regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(9):1522–1534. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.9.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Khissiin A, Leclercq G. Implication of proteasome in estrogen receptor degradation. FEBS Lett. 1999;448(1):160–166. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00343-9. doi:S0014-5793(99)00343-9 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wijayaratne AL, McDonnell DP. The human estrogen receptor-alpha is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially by agonists, antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(38):35684–35692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101097200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101097200 M101097200 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall NF, Peng J, Xie Z, Price DH. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(43):27176–27183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall NF, Price DH. Purification of P-TEFb, a transcription factor required for the transition into productive elongation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(21):12335–12338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devaiah BN, Lewis BA, Cherman N, Hewitt MC, Albrecht BK, Robey PG, Ozato K, Sims RJ, 3rd, Singer DS. BRD4 is an atypical kinase that phosphorylates serine2 of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(18):6927–6932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120422109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120422109 1120422109 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman S, Sowa ME, Ottinger M, Smith JA, Shi Y, Harper JW, Howley PM. The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(13):2641–2652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01341-10. doi:10.1128/MCB.01341-10 MCB.01341-10 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buratowski S. Progression through the RNA polymerase II CTD cycle. Mol Cell. 2009;36(4):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.019. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.019 S1097-2765(09)00784-9 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nechaev S, Adelman K. Pol II waiting in the starting gates: Regulating the transition from transcription initiation into productive elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809(1):34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.11.001 S1874-9399(10)00139-2 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kininis M, Isaacs GD, Core LJ, Hah N, Kraus WL. Postrecruitment regulation of RNA polymerase II directs rapid signaling responses at the promoters of estrogen target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(5):1123–1133. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00841-08. doi:10.1128/MCB.00841-08 MCB.00841-08 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel MC, Debrosse M, Smith M, Dey A, Huynh W, Sarai N, Heightman TD, Tamura T, Ozato K. BRD4 coordinates recruitment of pause release factor P-TEFb and the pausing complex NELF/DSIF to regulate transcription elongation of interferon-stimulated genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(12):2497–2507. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01180-12. doi:10.1128/MCB.01180-12 MCB.01180-12 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sengupta S, Biarnes MC, Jordan VC. Cyclin dependent kinase-9 mediated transcriptional de-regulation of cMYC as a critical determinant of endocrine-therapy resistance in breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143(1):113–124. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2789-2. doi:10.1007/s10549-013-2789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bihani T, Ezell SA, Ladd B, Grosskurth SE, Mazzola AM, Pietras M, Reimer C, Zinda M, Fawell S, D'Cruz CM. Resistance to everolimus driven by epigenetic regulation of MYC in ER+ breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2014 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2964. doi:2964 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.