Abstract

The Amazon River has the largest discharge of all rivers on Earth, and its complex plume system fuels a wide array of biogeochemical processes, across a large area of the western tropical North Atlantic. The plume thus stimulates microbial processes affecting carbon sequestration and nutrient cycles at a global scale. Chromosomal gene expression patterns of the 2.0 to 156 μm size-fraction eukaryotic microbial community were investigated in the Amazon River Plume, generating a robust dataset (more than 100 million mRNA sequences) that depicts the metabolic capabilities and interactions among the eukaryotic microbes. Combining classical oceanographic field measurements with metatranscriptomics yielded characterization of the hydrographic conditions simultaneous with a quantification of transcriptional activity and identity of the community. We highlight the patterns of eukaryotic gene expression for 31 biogeochemically significant gene targets hypothesized to be valuable within forecasting models. An advantage to this targeted approach is that the database of reference sequences used to identify the target genes was selectively constructed and highly curated optimizing taxonomic coverage, throughput, and the accuracy of annotations. A coastal diatom bloom highly expressed nitrate transporters and carbonic anhydrase presumably to support high growth rates and enhance uptake of low levels of dissolved nitrate and CO2. Diatom-diazotroph association (DDA: diatoms with nitrogen fixing symbionts) blooms were common when surface salinity was mesohaline and dissolved nitrate concentrations were below detection, and hence did not show evidence of nitrate utilization, suggesting they relied on ammonium transporters to aquire recently fixed nitrogen. These DDA blooms in the outer plume had rapid turnover of the photosystem D1 protein presumably caused by photodegradation under increased light penetration in clearer waters, and increased expression of silicon transporters as silicon became limiting. Expression of these genes, including carbonic anhydrase and transporters for nitrate and phosphate, were found to reflect the physiological status and biogeochemistry of river plume environments. These relatively stable patterns of eukaryotic transcript abundance occurred over modest spatiotemporal scales, with similarity observed in sample duplicates collected up to 2.45 km in space and 120 minutes in time. These results confirm the use of metatranscriptomics as a valuable tool to understand and predict microbial community function.

Introduction

The Amazon River discharges an average of 1.55 × 105 ± 0.13 m3 s-1 at Obidos, Brazil, ultimately resulting in a thin, fresh water layer at the surface called the Amazon River plume (ARP), which also varies seasonally and covers up to 1.3 × 106 km2 of the western tropical North Atlantic Ocean [1–4]. The ARP harbors many distinct microbial communities along the salinity gradient [5]. In lower salinity waters, where dissolved nutrients such as silica, iron, nitrate and phosphate are abundant, coastal diatom communities flourish once light can penetrate the initially turbid plume [4, 6]. Once ammonium and nitrate are depleted in the mesohaline portions of the plume, diatom-diazotroph association (DDA) blooms utilize the remaining silica while endosymbiotic cyanobacteria fix nitrogen and transfer it to the diatoms [4, 7]. There are at least 4 genera of diatoms (Hemiaulus, Rhizosolenia, Chaetocerous, Guinardia) which form partnerships, or symbioses, with nitrogen fixing heterocystous cyanobacteria (Richelia intracellularis and Calothrix rhizosoleniae) and collectively these are referred to as DDAs [8]. These DDA blooms exhibit high rates of nitrogen and carbon fixation worldwide [4, 9]. DDA blooms in the ARP sequester 1.7 Tmol of carbon annually [4], and similar distributions of DDAs have been reported in the Niger and Congo river plumes as well as the South China Sea [10, 11]. When silica and phosphate are no longer available, nitrogen-fixing Trichodesmium dominate, which have been shown to regulate their buoyancy with gas vesicles to acquire phosphorus at depth [12].

Metatranscriptomics, the collection and analysis of mRNA from a community of organisms, allows us to study fluctuations in the molecular response of natural communities to changing environmental conditions. The first report to describe an environmental metatranscriptome was that of Poretsky et al. who built primarily prokaryotic mRNA libraries derived from Sapelo Island Microbial Observatory (SIMO, a tidal creek in a salt marsh) and the Mono Lake Microbial Observatory (MLMO, a hypersaline soda lake) [13]. Metatranscriptomics can elucidate how communities respond to environmental changes, including, for example, temperature effects on eukaryotic phytoplankton metabolism [14], oil spill impacts on deep bacterioplankton [15], and differences in free-living or particle-associated habitats [16]. Although much has been published about river plume communities [6, 17–20], including some findings about individual gene expression [21], metatranscriptomic analysis of microbial eukaryotes has not yet been performed to examine the difference in gene expression as a measure of metabolic activity along a river plume salinity gradient.

Reported here are findings from part of two large, multi-investigator research programs: the River Ocean Continuum of the Amazon (ROCA) and Amazon iNfluence of the Atlantic: CarbOn export from Nitrogen fixation by DiAtom Symbioses (ANACONDAS). We have used metatranscriptomics to show how the expression of 31 genes relates to the nitrogen, silica, phosphate, and carbon gradients in the ARP. Focusing a large dataset on minimal genes is crucial to make models where the appropriate caluclations can be performed across the entirety of the tropical Atlantic. In particular, these 31 genes enable inferences to be drawn on the physiologic status of communities such as the DDAs. We also demonstrate that replicates taken up to two hours and 2.4 km apart still show similar patterns of gene expression across the 31 genes analyzed. Modeling efforts are currently using these data to expand predictive capabilities of their ARP ecological models [22].

Materials and Methods

A detailed discussion of sample collection, DNA and mRNA processing, sequencing, and metadata collection can be found in a sequence-release announcement [23]. DNA samples were taken at the same stations, but with different filters. DNA methods are fully described in the sequence-release announcement [23]. These methods and the location of the metadata used are briefly summarized below.

Sample Collection

All samples reported here were collected during the May-June 2010 ANACONDAS expedition onboard the U.S. RV Knorr (KN-197-8; http://www.bco-dmo.org/project/2097). At each of the six stations selected for metatranscript analysis, near-surface water (upper 3 m) was collected at about the same time of day (just after local sunrise) by gentle impeller pumping (modified Rule 1800 submersible pump) through 10 m of Tygon tubing (3 cm diameter) to the ship’s deck where the water was pre-filtered through a 156 μm mesh into 20 L carboys. The water was immediately taken to the shipboard laboratory, and gently filtered (using a Masterflex peristaltic pump) through a 2.0 μm pore-size, 142 mm diameter polycarbonate (PCTE) membrane filter (Sterlitech Corporation, Kent, CWA). After < 30 minutes of filtration, membranes were submerged in RNAlater (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) in sterile 50 ml conical tubes, incubated at room temperature for at least 4 hours, stored onboard at -80°C, shipped in liquid nitrogen, and archived at -80°C until RNA extraction. All filtration and fixation was completed within 30 min of water collection, and the volume of filtrate passed through each membrane was recorded. A second (duplicate) sample was collected similarly for each station in the same general area (within 2.5 km) within two hours of the first sample.

RNA Processing for Eukaryotic Metatranscriptomes

Prior to RNA extraction, filters were thawed, removed from the preservative solution, placed in Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco, Fort Artkinson, WI), and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. A lysis tube was prepared for each sample consisting of a sterile 50 ml conical tube containing 10 ml of RLT Lysis Solution and 1.5 ml of 100 μm zirconium beads (OPS Diagnostics, Lebanon, NJ, USA). The brittle filters inside the bags were broken into small pieces using a rubber mallet and transferred to the lysis tubes. Tubes were vortexed for 10 min to lyse cells, and RNA was purified from cell lysate using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Following lysis, poly(A)-tailed mRNA was isolated from total RNA using an Oligotex mRNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and mRNA was linearly amplified with one round of the MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). mRNA was converted into cDNA using the Superscript III First Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with random primers, followed by the NEBnext mRNA second strand synthesis module (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), both according to manufacturer protocols. The 3’ adenine overhang was removed with T4 polymerase and the cDNA was purified using the DNA Clean and Concentrator -25 Kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA) with five volumes of DNA binding buffer. DNA was resuspended in 100 μL of TE buffer, and stored at -80°C until sample preparation for sequencing.

Sequencing

cDNA was sheared ultrasonically to ~200–250 bp fragments and TruSeq libraries (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) were constructed for paired-end (150 x 150) sequencing using the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx, HiSeq2000, MiSeq, or HiSeq2500 platforms (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA).

Bioinformatics

Paired-end reads were joined using the She-ra program [24] with a quality metric score of 0.5. Paired reads were trimmed using Seqtrim 20 [25]. Poly(a)-RNA capture methods were not 100% successful, as some rRNA would remain in the sample, so the minimal (0.14–0.33%) rRNA were removed in silico after sequencing. Remaining rRNA reads in the metatranscriptomes were removed via a Blastn against a database containing rRNA sequences from Genbank. Reads with a bit score >50 to one of the sequences in the database were removed. Reads representing genes or transcripts of 31 selected proteins (database described below) were identified using a Blastx search with a bit score cutoff of 40 against a custom database consisting of multiple reference sequences from diverse taxa for each gene, along with their paralogs to eliminate false-positives. Sequences that hit the targeted gene database were subsequently queried against RefSeq protein database using Blastx to confirm the functional assignment of the reads and to obtain taxanomic designations.

The custom database used contained thirty-one well characterized genes representative of key biological functionality such as carbon autotrophy and heterotrophy and nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and silicon cycling. Ten to twenty amino acid sequences covering a broad range of taxonomy were used as reference sequences for each protein, and sequences representative of paralogs for the selected genes were also included in the database to eliminate false-positives. As often as possible, genes were collected directly from physiological papers where the specific sequences were originally identified and sequenced. This gene-specific reference database was tested on a subset of Amazon reads using a bit score >40, and a re-analysis of the positive reads against the RefSeq protein database was used to adjust the composition of the database.

Metagenomic sample collection and processing were performed by collaborators, and detailed methodology has been previously published [23]. True replicates were utilized at each station to collect the metagenomics samples. Metagenomic sequences were searched for 18S rDNA candidates via matching for a 18S reference covariance model using Infernal [26]. A Blastn [27] search was performed against SILVA [28] (release 115) to identify study-specific taxa to be included in the reference tree, in addition to a predefined set of core sequences representing the major eukaryotic lineages. The search was executed on a TimeLogicDeCypher system (Active Motif Inc., Carlsbad, CA) with e-value threshold ≤ 1E-100. Reference sequences were then aligned with MAFFT [29] using the G-INS-i setting for global homology. The generated multiple sequence alignment was visually inspected and manually edited and refined using JalView [30]. A maximum likelihood reference tree was inferred under the general time-reversible model with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity and an estimated proportion of invariant sites (GTR + Γ + I), implemented in RAxML [31] and the bootstrap support values assessed with the extended majority-rule consensus tree (autoMRE) criterion [32]. The predicted metagenomic 18S rDNA sequences were mapped onto the reference tree using pplacer [33] with the default settings. The counts of the sequences affiliated with the nodes on the reference tree were normalized to the total number of sequences from their corresponding samples. The normalized abundances are visualized as circles mapped on the reference tree such that the diameters of the circles are proportion to the taxonomic abundances. No corrections were applied to account for a difference in 18S copy number per species.

Nitrate transporters (NRT) were analyzed by performing hmmsearch [34] for the NCBI CDD nitrate transmembrane transporter models, PLN00028 and NarK (COG2223) for eukarya and bacteria, respectively. Similarly, hmmsearch was performed against a comprehensive reference database compiled from NCBI RefSeq [35] (release 60), microbial eukaryotic genomes from JGI (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/), and the recently released microbial eukaryotic transcriptomic libraries by MMETSP (http://marinemicroeukaryotes.org/). The sequences from the reference databases were used to infer a reference phylogenetic tree for the NRTs. Reference sequences were aligned with MAFFT [29] using the E-INS-i setting for multiple conserved domains and long gaps. The multiple sequence alignment was visually inspected and manually refined using JalView [30]. A maximum likelihood reference tree was inferred under the WAG model for amino acid substitutions [36] with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity and an estimated proportion of invariant sites (WAG + Γ + I), implemented in FastTree [37]. The branch confidence values were estimated using the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH) test [38] with 1,000 resampling replicates. The NRT environmental ORFs were mapped onto the reference tree using pplacer [33] with the default settings. The numbers of ORFs affiliated with the nodes on the reference tree were normalized to the total number of reads from the corresponding samples. The normalized expression levels are visualized as circles mapped on the reference tree such that the diameters of the circles are proportional to the expression levels.

Sequence Availability

Sequences are available from the iMicrobe (data.imicrobe.us) database under project number CAM_P_0001194. The sequences are quality controlled fasta files of joined paired-end reads following removal of rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only). Sequences are also available from NCBI under accession numbers [SRP039390] (metagenomes) and [SRP039544] (poly(A)-selected metatranscriptomes). The NCBI sequences are fastq files from which rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only) have been removed prior to deposition.

Metadata

Environmental data (temperature, salinity, beam transmittance, dissolved oxygen, pCO2, etc.) have been previously published [2, 23], as have nutrient and community structure data corresponding to the stations examined [5, 23, 39, 40]. The abundances of the diazotroph population was determined by epifluorescence microscopy as previously described [41]. ANACONDAS and ROCA project data are also available at the BCO-DMO data repository (http://www.bco-dmo.org/project/2097).

Results and Discussion

Hydrographic Conditions and Community Structure

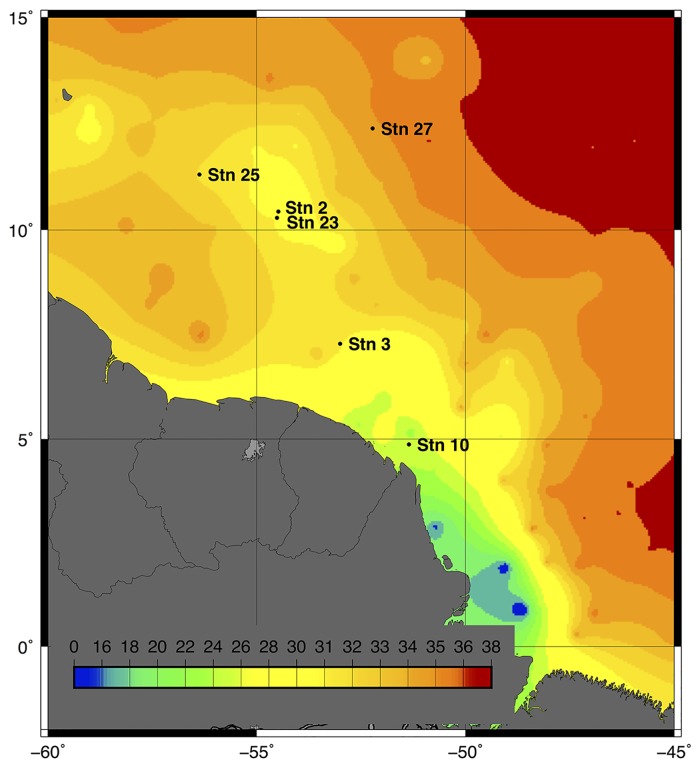

The eukaryotic population in the >2.0 μm size fractioned surface water (156 μm pre-filtered) was examined at six unique stations (duplicate samples at each location, total of 12 samples). Of the 6 stations we sampled (Fig 1; Table 1), one (Sta. 10) was in the coastal plume on the shallow continental shelf (lowest salinity of 21.7 PSU), two (Sta. 3 and 23) were in the near outer plume (salinity of 26–30 PSU), two (Sta. 2 and 25) were in the mesohaline zone (salinity of 31) expected to favor DDAs, and one (Sta. 27) was in the far outer plume or oceanic zone (salinity >35). Stations 2 (surface salinity 31.4 PSU) and 23 (surface salinity 26.2 PSU) were sampled geographically near each other, but about three weeks apart, illustrating the dynamic nature of the plume by their salinity difference.

Fig 1. Salinity map of the May/June 2010 Amazon River Plume cruise aboard the RV Knorr.

Salinity (PSU) from the underway system along the ship track was augmented with National Oceanographic Data Center profiles in regions of low coverage then interpolated and contoured.

Table 1. Metadata for stations sampled in the ARP.

Measurements taken in conjunction with the metatranscriptomes are listed here. Asterisks highlight where concentration of the variable was below limit of detection.

| Station | Latitude | Longitude | Date Sampled | Salinity | Sea Surface Temperature (°C) | Mean Phosphate (μM) | Mean Silica (μM) | Mean NO3 + NO2 | CTD Beam Transmittance | DIC | Diatom Microscope Count (cells/L) | Hemialius Microscope Count (cells/L) | Chl (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 10.29 N | 54.51 W | 5/25/10 | 31.362 | 28.87 | 0.11 | 7.34 | 0* | 89.20 | 1802 | 165,935 | 164,531 | 3.251 |

| 3 | 7.29 N | 53.00 W | 5/26/10 | 30.086 | 28.96 | 0.19 | 17.03 | 0* | 92.37 | 1846 | 125,962 | 1,049 | 0.580 |

| 10 | 4.88 N | 51.36 W | 6/5/10 | 21.721 | 29.61 | 0.39 | 38.48 | 0.188 | 46.12 | 1372 | 6,940,996 | 0* | 36.107 |

| 23 | 10.62 N | 54.40 W | 6/16/10 | 26.177 | 29.51 | 0.37 | 26.33 | 0* | 93.81 | 1575 | 26,322 | 3,210 | 0.150 |

| 25 | 11.32 N | 56.43 W | 6/18/10 | 31.310 | 29.43 | 0* | 2.81 | 0* | 85.83 | 1774 | 372,113 | 371,000 | 5.250 |

| 27 | 12.41 N | 52.22 W | 6/21/10 | 35.311 | 28.65 | 0.27 | 1.23 | 0* | 95.03 | 1992 | 1,608 | 402 | 0.129 |

Transcript counts were normalized by sample-size. Duplicates at each station were analyzed to determine variation in gene expression over distance and time sampled. A direct comparison of normalized transcript counts between duplicates were very similar (R = 0.922) over all the stations (S1 Fig). The average difference between duplicate transcript counts was 11.43%. The similarity in duplicates over space and time suggests that expression levels of microbial eukaryotic communities can be stable over distances of up to 2.45 km (station 23) and time intervals of up to 2 h (station 10), when environmental factors such as salinity, temperature, illumination, and nutrient concentrations are also similar. This is an important result, because previous work has only demonstrated a stability in transcription abundance in environmental samples within eight minutes [42]. Had there been large transcriptional differences in the 31 examined genes, without commensurate environmental change, these data would be difficult to link to biogeochemical cycling or model development. These data suggest that, for at least a subset of genes, transcripts that relate to the local environmental conditions can be used to assess the role of the eukaryotic microbial communities in biogeochemical cycles. Replicates also have been shown to provide greater transcript detection power compared to an increased sequence depth, highlighting the importance of replicates in measuring differences in transcript activity among genes with low mRNA copy number [43]. Duplicate sample values are presented as the average of the duplicates in the ensuing analysis described below.

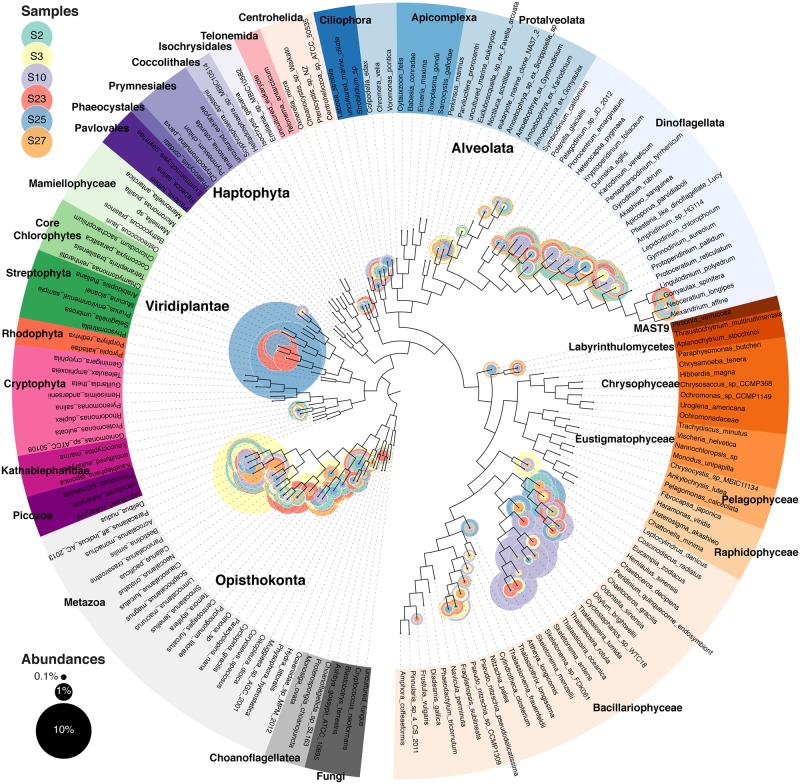

Eukaryotic community structure varied across the six stations (Fig 2, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7 Figs). Despite the 156 μm prefilter, larger cells were still observed due to the filtering process breaking chains and lysing cells. Over all six stations, the 18S rDNA recovered was 19.2% ± 2.5% diatom, 18.04% ± 4.3% dinoflagellate, and 38.50% ± 3.8% metazoan origin. Since the 18S rDNA gene has variable copy numbers per genome, relative abundance using 18S results do not represent absolute community abundance [44]. Station 10, with the lowest surface salinity and the only detectible dissolved inorganic nitrogen concentration (0.18 μmol L-1), contained a large diatom bloom consisting principally of the centric diatoms Thalassiosira and Cyclostephanos (S5 Fig), according to best Blastn hit. The thick patches of Chl a in conjunction with elevated inorganic nitrogen levels agrees that this station had a large mixed population of diatoms [5]. Hemiaulus sp., a diatom, which often forms a DDA with the endosymbiotic cyanobacteria Richelia intracellularis, was found in the 18S rDNA sequences at stations 2, 10 and 25. R. intracellularis was also confirmed in these stations due to the elevated concentrations of PE-2 phycobilipigments [5]. This Hemiaulus sp. population was confirmed by epifluorescence microscopy at only stations 2 and 25 (Table 1), suggesting that the limit of detection is lower for the metagenome and that low abundances of DDAs may occur even when inorganic nitrogen is available. Station 25 had more abundant Hemiaulus cells (3.71 x 105 cells L-1) than station 2 (1.64 x 105 cells L-1). Epifluorescence microscopy observations indicated a healthy DDA community at station 2, as the DDAs had brightly fluorescent chloroplasts and formed long chains, while DDA chains from station 25 were short and/or broken and had weak fluorescence, suggesting bloom senescence.

Fig 2. Metagenomic profiling of 18S rDNA for all six stations.

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Each circle represents one branch, and sizes are proportional to the normalized taxonomic abundances. Individual trees for each station can be found in Supplemental Materials (S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7 Figs).

Low levels of Hemiaulus were also found at stations 3 and 23, and the phytoplankton communities displayed the salinity transition from station 10 to stations 2 and 25. One exception to this is that the diatom Leptocylindrus danicus (a typically estuarine diatom)[45] was numerous as station 3 and Chaetocerous decipiens (a typically coastal diatom)[46] was most abundant at station 23. These intermediate plume stations contained the largest metazoan population, largely consisting of Bestiolina similis, a copepod known to be at high abundance in nearshore waters [47] (S3 and S5 Figs). Since this organism should have been captured in the prefiltering process, this signal is likely eggs or nauplii larvae to that passed through [48].

The 18S rDNA data at Station 25 also suggest a large embryophyte (land plants) signature (51.09% of 18S rDNA). The sequences align weakly with the Mucuna genus, which consists of climbing vine and shrub vascular plant. Rafts of terrestrial plant debris were occasionally observed in the plume, so it is possible we collected some of that material. Chlorophytes have very similar 18S rDNA sequences, however, and due to short sequence length, these “embryophytes” may have instead represented an uncultured chlorophyta.

Oceanic station 27 was the most oligotrophic station, with the highest surface salinity (35.3), undetectable dissolved inorganic nitrogen, and the lowest eukaryotic phytoplankton cell counts (Table 1). Here, the DDAs observed by epifluorescence microscopy had empty frustules. The 18S phylogenetic data suggests this station was the station with the largest proportion of dinoflagellates, with Gyrodinium rubrum and Apicoporus parvidiaboli as the most abundant species. The dinoflagellate population has been reported to exist in much smaller numbers throughout the plume compared to the other phytoplankton groups [5].

Expression of Key Biogeochemically-Relevant Genes

Station 10 had the highest number of total transcripts for 16 of 31 genes (Table 2), and also had the highest chlorophyll a concentration and the only measurable dissolved inorganic nitrogen (Table 1). This outcome is likely a function of the thriving coastal diatom bloom fueled by riverine nutrients (e.g., nitrate, phosphate, silicate). At all the stations, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH, carbon heterotrophy) was the most highly expressed in terms of transcript number of all 31 genes. At Station 10, the eukaryotic nitrate transporter (NRT) was also expressed, along with two carbon autotrophy genes (delta carbonic anhydrase and transketolase). At stations 3 and 23, NRT was less abundant than at Station 10 and the ammonium transporter (amtB) increased in its relative importance. Stations 2 and 25 were unique in their high expression of photosystem II D1 protein (psbA) and a silicon transporter (SIT). Two of the three most abundant genes at station 27 were acetoacetyl-CoA reductase and polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis (consisting of both beta-ketothiolase and NADPH-linked acetoacetyl coenzyme A reductase), and the relative contribution of autotrophic genes were minimal, signifying that at this nutrient-poor station, carbon heterotrophy was dominating.

Table 2. Sample size-normalized gene counts for the 31 biogeochemically-relevant genes.

Values are the average of the duplicate samples, per 10 million sequences. Bolded/underlined numbers highlight the highest expression for that gene.

| Gene Abbreviation | Gene Name | Station 2 | Station 3 | Station 10 | Station 23 | Station 25 | Station 27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcL_IB | RuBisCO form IB | 7 | 46 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 1 |

| rbcL_ID | RuBisCO form ID | 24 | 15 | 75 | 2 | 27 | 1 |

| psbA | Photosystem II protein D1 | 9005 | 350 | 1487 | 106 | 8493 | 78 |

| a-CA | Carbonic anhydrase (alpha) | 216 | 367 | 332 | 266 | 179 | 161 |

| d-CA | Carbonic anhydrase (delta) | 740 | 484 | 2388 | 498 | 461 | 466 |

| tkt | Transketolase | 1117 | 697 | 2082 | 269 | 620 | 180 |

| casE | Chitinase | 277 | 565 | 110 | 182 | 385 | 171 |

| Chs3p | Chitin synthase III | 2 | 17 | 552 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| bglA | Beta-glucosidase | 516 | 413 | 313 | 491 | 386 | 345 |

| GADPH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 12782 | 6869 | 16908 | 6043 | 12237 | 6931 |

| GPI | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 229 | 339 | 584 | 192 | 249 | 231 |

| metF | Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase | 379 | 148 | 175 | 106 | 287 | 130 |

| phaB | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase | 1676 | 1734 | 1883 | 1258 | 1478 | 1141 |

| phaA | Beta-ketothiolase | 1125 | 1294 | 898 | 1079 | 876 | 1063 |

| AA_Permease | Amino acid permeases | 236 | 188 | 536 | 100 | 287 | 64 |

| AAP | Alanine aminopeptidase | 106 | 116 | 236 | 62 | 70 | 54 |

| LAP | Leucine aminopeptidase | 370 | 684 | 557 | 442 | 282 | 251 |

| amtB | Ammonium transporter | 340 | 170 | 217 | 211 | 263 | 144 |

| ProAP | Proline aminopeptidase | 213 | 294 | 297 | 246 | 169 | 144 |

| UT | Eukaryotic urea transporter | 128 | 204 | 661 | 171 | 96 | 51 |

| MetAP | Methionine aminopeptidase | 417 | 503 | 613 | 456 | 363 | 355 |

| NAT | Eukaryotic nitrate transporter | 563 | 212 | 7960 | 175 | 325 | 27 |

| pitA | Low affinity phosphate transporter | 484 | 72 | 216 | 153 | 182 | 80 |

| ppk2 | Polyphosphate kinase 2 | 82 | 112 | 66 | 73 | 54 | 102 |

| cysK | Cysteine synthetase A | 294 | 353 | 447 | 278 | 246 | 217 |

| Xsc | Sulfoacetaldehyde acetyltransferase | 63 | 62 | 48 | 85 | 53 | 42 |

| SiR-beta | Sulfite reductase (beta subunit) | 118 | 104 | 370 | 68 | 137 | 37 |

| SIT | Silicon transporter family | 2046 | 400 | 1053 | 280 | 1666 | 215 |

| pdxH | Pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase | 89 | 74 | 29 | 45 | 109 | 199 |

| pdxK | Pyridoxinal (pyridoxine, vitamin B6) kinase | 30 | 10 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 22 |

| thiC | Phosphomethylpyrimidine synthase | 1 | 2 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

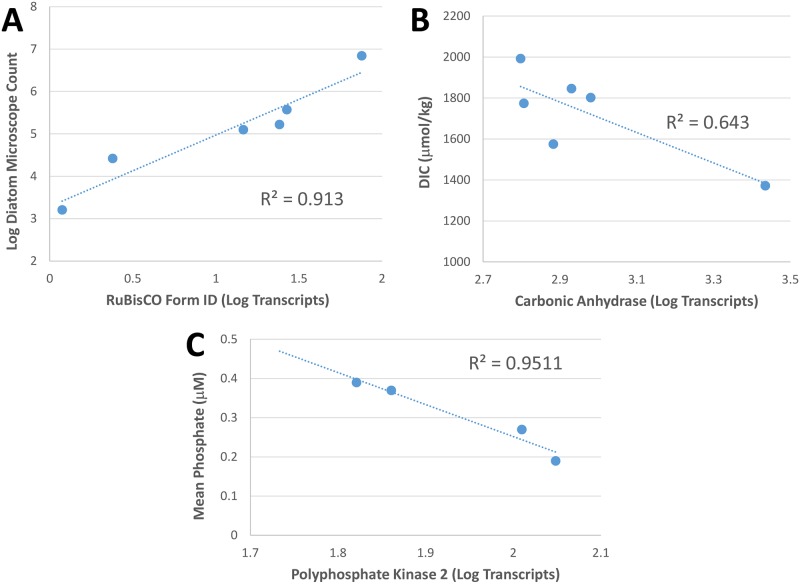

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) is a key enzyme for carbon fixation, and the different forms of RuBisCO yield important information on the carbon fixing populations present. The large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (rbcL) is a gene found in the chloroplast of many phytoplankton, where transcripts are not usually poly(A)-tailed. The poly(A)-tailed rbcL transcripts found are likely the result of post transcriptional modification, where chloroplast transcripts are polyadenylated to accelerate exoribonucleolytic degradation [49]. Form IB rbcL from Streptophyta, Chlorophyta, and Euglenozoa [50] was more strongly expressed at stations 3, 10 and 23, whereas Form ID, found in diatoms [50], and was most abundant at stations 2, 10 and 25, where diatom blooms were observed. As might be expected, a correlation occurred between diatom abundance (from microscope counts) and log RuBisCO form ID transcript abundance (R = 0.956; Fig 3A).

Fig 3. Transcriptomic versus biogeochemical data.

Panel A: The correlation between diatom microscope counts and log RuBisCO Form ID transcripts counts. Panel B: The inverse relationship of carbonic anhydrase transcript abundance to DIC concentration. Panel C: The inverse relationship between polyphosphate kinase transcript abundance and phosphate concentration. Station 2 and 25 had little or no phosphate, due to the diatom bloom, however ppk was not upregulated.

Photosystem II protein D1 (psbA) is responsible for binding chlorophylls, quinones and metal ligands in the photosystem II reaction center. This protein undergoes rapid, light-dependent turnover (the “photosystem II repair cycle”). Under illumination psbA degrades, and repair or re-synthesis of the D1 protein is necessary to limit the accumulation of photodamaged photosystem II proteins [51]. Photodegradation of the D1 protein occurs under any illumination at a rate roughly proportional to the transfer of excitation energy to the reaction center [51]. The eukaryotes at DDA stations had higher concentrations of psbA transcripts than other stations. At the mesohaline DDA stations, there was less chromophoric dissolved organic matter; with the high CDOM from the river being diluted by low-CDOM oceanic water [52, 53], increasing light transmittance (Table 1). The upregulation of psbA may be a repair mechanism for photosynthetic blooms in clearer waters to combat high incident irradiance penetration, especially for a rapidly photosynthesizing community. Bloom senescence at station 25 may explain the slightly lower psbA transcript counts recovered from that environment. We might expect to see it also expressed well at station 27, but we did not; likely this is because there are so few diatoms there.

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is responsible for the interconversion of bicarbonate and carbon dioxide and is a critical component of carbon concentrating mechanisms of photoautotrophs. Chlorophytes contains α-CA [54], which was most highly expressed at stations 3 and 10, where rbcL Form IB was also highly expressed signifying chlorophyta populations. δ-CA, which is commonly found in diatoms [55], was highly expressed at stations 2 and 10 relative to the other stations, and this same pattern was detected with rbcL Form ID, which is the form used in haptophytes, rhodophyta and heterokonts (including diatoms) [50]. There was a strong inverse correlation between DIC concentration and total CA transcripts (R = 0.802, Fig 3B). As CO2 becomes depleted due to high rates of photosynthesis, organisms expressing CA genes will be more successful in supplying CO2 to their carbon fixation machinery. Transcript abundance for transketolase (tkt), part of the reductive Calvin-Benson-Bassham Cycle, showed a similar, although weaker, inverse relationship with DIC (R = 0.58).

Available nitrogen plays a large role in determining the abundance and composition of marine phytoplankton populations globally [8]. Since ammonium requires less energy to assimilate than other forms of nitrogen in seawater, it often is the preferred nitrogen source for phytoplankton growth. Nitrate is usually used by phytoplankton if other forms of reduced nitrogen (ammonium, urea) are absent and there is an appreciable amount of nitrate to support high growth rates [56, 57]. A large phytoplankton bloom made up of chain-forming diatoms, was present at Station 10, where eukaryotic nitrate transport (NRT) expression was highest. Station 10 was also the only station with measurable dissolved nitrogen (Table 1). If an appreciable amount of ammonium is available, it strongly downregulates NRT expression [58], signifying that ammonium concentrations (not measured) were not high enough to support this diatom bloom. A phylogenetic analysis of expressed NRT genes revealed that most of the transcription was carried out by the diatom Chaetoceros and the chlorophyte Micromonas (S8 Fig), which were also observed to be highly abundant through epifluorescent microscopy. The lack of detectable nitrate at the other stations explains low abundance of NRT transcripts at these stations since slower growth rates can be supported by ammonia utilization. Cell-surface ammonium transporter (amtB) expression levels were highest at the DDA stations, where the extracellular endosymbionts (residing between the plasmalemma and silica wall) fix nitrogen and transfer it to diatoms [7], possibly in the form of ammonium [58]. Urea occurs frequently in nature as a result of release of nitrogenous wastes and is considered “recycled N”. Urease, synthesized by almost all organisms, is used to hydrolyze urea to carbon dioxide and ammonia. This conversion provides an important nitrogen source in otherwise nitrogen-limited environments. However, the Richelia and Calothrix symbionts in the DDAs lack both urease and urea transporters [59]. We observed that the urea transporter (UT) showed the highest transcript abundance at stations closest to the mouth of the river, most likely caused by the terrestrial input of urea.

The low affinity phosphate transporter (pitA) is highly expressed at station 2, consistent with a thriving phytoplankton bloom with available inorganic phosphate (Pi). PitA is expressed when Pi is plentiful, but when concentrations of Pi are low, the high affinity phosphate transporter is induced instead [60]. Station 25 was the only station without detectable Pi, and consequently had low expression of pitA. Polyphosphate kinase (ppk) catalyzes the reversible transfer of the terminal phosphate of ATP to form a long chain polyphosphate [61]. A biochemical characterization of ppk in eukaryotes has not been reported, and with the reaction being reversible, interpreting the differing levels of expression is problematic. Nonetheless, with the removal of data from the DDA stations 2 and 25, there was a correlation of ppk transcript abundance and phosphate concentration (R = 0.975, Fig 3C). These stations have little or no measureable phosphate and are likely using some other method for acquiring phosphorus. This strong correlation at the other four stations suggests that cleavage of a terminal phosphate from a polyphosphate may be a scavenging technique for microbial eukaryotes under phosphate depleted (impoverished) conditions [62].

Silica transport is required for the synthesis of diatom frustules. Diatoms need to maintain an intracellular concentration of soluble silica sufficient for complete cell wall synthesis, which generally occurs within an hour [63]. Regulation of synthesis is necessary to prevent polymerization prior to deposition [63]. Consequently, all silica transporter proteins (SIT) are induced at once, just prior to the maximum incorporation of silica into the cell wall [63]. High expression of SIT signifies a rapidly dividing diatom population, as observed at the diatom abundant stations 2, 10 and 25. Station 27, with the smallest diatom population and the lowest silica concentration had the lowest SIT expression.

The abundance of chitinase (casE) and chitin synthase (Chs3p) transcripts together can account for the fate of chitin in the microeukaryotes in the ARP. Chitin synthase can be found in both copepods and diatoms, however since copepods were only minimally represented in station 10, due to the prefilter, the measured chitin synthase expression is likely from diatoms containing this gene, such as Thalassiosira and Cyclotella [64, 65]. Diatoms produce chitin to decrease sinking rates by increasing buoyancy with extruding chitin fibers from the frustule pores [65, 66]. These chitin fibers can account for up to 40% of the total cell biomass [67]. Another role for chitin in diatoms is as a substitute constituent of cell walls during long-term silicic acid starvation [68]. However this is unlikely to be the case in our samples because the station with the highest Chs3p expression (Station 10) had the highest silica concentration (39.30 μmol L-1). Some diatoms at station 10 were very large (>150 μm), and likely were using Chs3p to decrease sinking rates. Chitinase expression was highest at Station 3, and then also relatively high in stations 2 and 25, possibly in response to metabolizing the chitin produced by the larger diatoms.

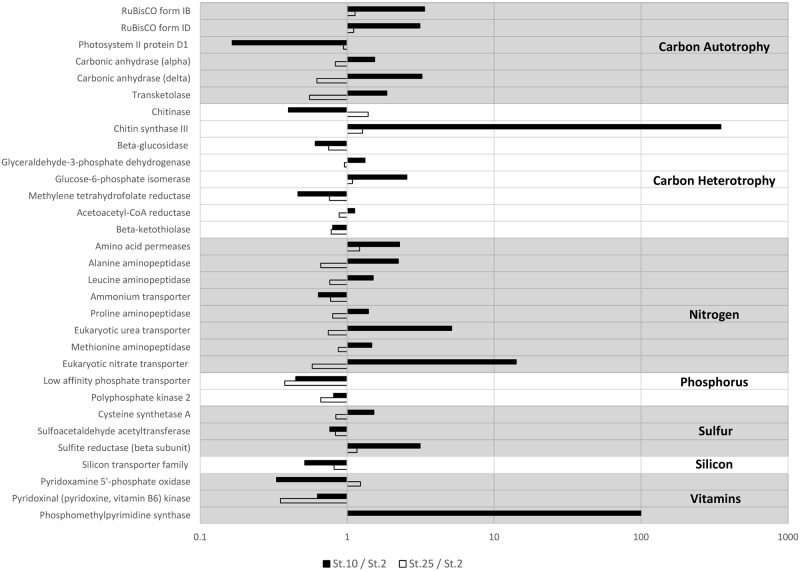

Patterns of Gene Expression

Our hypothesis is that relative magnitude of transcription of certain important biogeochemical gene functions in seawater samples often reflects or correlates with biogeochemical processes taking place at the point and time of sampling, and these data support this hypothesis. For example, high expression of psbA co-occurred in surface phytoplankton populations in clear water (Stations 2 and 25). Furthermore both SIT and Form ID rbcL are diagnostic of healthy diatom populations. High expression of NRT signified that nitrate was utalized to fuel high growth rates, as observed at station 10. Using a combination of these predictable differences of transcript abundances, or ‘patterns of gene expression’, biogeochemical processes can be related to the transcripts observed.

Direct comparisons by ratios between the patterns of gene expression at the three stations which were abundant in diatoms illustrates how these data reveal the deviations between the stations (Fig 4). Station 10 shows high expression of chitin synthase III, perhaps for buoyancy or defense [69], and NRT due to the nitrate availability. Despite being sampled 238.3 km and 25 days apart, the DDA stations 2 and 25 show very little deviation between transcript counts, with the average difference between transcript abundance being 9.33%. This evidence supports the notion that patterns of gene expression are stable in similar microbial eukaryote communities living in similar environments and thus suggests that the biogeochemistry and microbial communities are intricately linked.

Fig 4. Ratios of transcript abundance at stations 10:2 (black bars) and 25:2 (white bars).

Station 10 has very high levels of eukaryotic nitrate transporter as well as chitin synthase compared to station 2. Note log scale. Stations 2 and 25 perform similar functions in the ARP. Thus the plot of the ratio of Station 25: Station 2 has smaller values than the ratio of stations 10 and 2.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that metatranscriptomic analysis of 31 pre-selected biogeochemically-relevant genes allowed for a reliable analysis of eukaryotic planktonic communities and their physiological status in the ARP. A stability in patterns of gene expression of similar planktonic communities over space and time was demonstrated, allowing for better resolution through replicates. Phylogenetic information from 18S rDNA enabled taxa to be assigned to the short length transcript sequences collected from these environments and transcription was related to environmental conditions, supporting that a metatranscriptomic study can be used to describe the biogeochemistry. This study showed that DDA blooms are capable of upregulating expression for their photosystem II D1 protein and in acquiring silica. The small differences between their expression at exponential growth phase and senescing populations can be further explored in culture. In lower salinity, non-DDA diatom blooms, nitrate transporters are activated to use nitrate to support their high growth rates, and carbonic anhydrase (carbon concentrating mechanism) allowing these diatoms to thrive in low-CO2 waters. Finally, chitin synthase was hypothesized to be a mechanism used by diatoms in lower-salinity plume waters to decrease their sinking rates, as light is also limiting in these young plume waters. These results, in conjunction with ongoing modeling efforts, will help us understand the river plume microbial communities in this globally important ecosystem. Future research will involve sampling the ARP in different seasons, comparing the different patterns of gene expression between seasons, and using those data to ground-truth the ecosystem models.

Supporting Information

The dotted line represents the 1:1 line of identity. The 186 data points represent the 31 genes measured at 6 stations. The average difference between replicate transcripts was 11.43%.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

A maximum likelihood tree was used with the placement of metatranscriptomic predicted open-reading frames. Bootstrap support values ≥ 50% are shown. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized expression levels. Branch lengths are log10-transformed.

(TIF)

Compiled data of all the sequences obtained and analyzed at the six stations. Duplicate samples were pooled to account for variations in the data that may occur from only taking one sample.

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation as part of the River Ocean Continuum of the Amazon (ROCA) project (Grants GBMF #2293 and #2928). The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the cruise and all the supporting data (Grant NSF-OCE 0934095; RAF is funded by NSF-OCE 0929015); JPMcCrow, AEA and AM were funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Grant GBMF #3828) and the NSF (Grant OCE-1136477). We thank the captain and crew of the RV Knorr for excellent at-sea support. The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

Sequences are available from the iMicrobe (data.imicrobe.us) database under project number CAM_P_0001194. The sequences are quality controlled fasta files of joined paired-end reads following removal of rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only). Sequences are also available from NCBI under accession numbers [SRP039390] (metagenomes) and [SRP039544] (poly(A)-selected metatranscriptomes). The NCBI sequences are fastq files from which rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only) have been removed prior to deposition. Environmental data (temperature, salinity, beam transmittance, dissolved oxygen, pCO2, etc.) have been previously published (references 2, 23), as have nutrient and community structure data corresponding to the stations examined (references 5, 23, 39, 40). The abundances of the diazotroph population was determined by epifluorescence microscopy as previously described (reference 41). ANACONDAS and ROCA project data are also available at the BCO-DMO data repository (http://www.bco-dmo.org/project/2097).

Funding Statement

Funding was provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation as part of the River Ocean Continuum of the Amazon (ROCA) project (Grants GBMF #2293 and #2928). This funded BLZ EJC VJC BCC MD RAF JIG RG RRH J.P. Montoya BMS SS CBS PLY and JHP. This agency contributed to the study design and the data analysis only. They encourage publication of the data. Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation funded AEA, J.P. McCrow and AM (Grant #3828). This agency contributed to the study design and the data analysis only. They encourage publication of the data. The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the cruise and all the supporting data (Grant NSF-OCE 0934095). This funded BLZ EJC VJC BCC MD RAF JIG HRG RRH J.P. Montoya BMS SS CBS PLY and JHP. This agency had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded RAF (Grant NSF-OCE 0929015). This agency had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded AEA J.P. McCrow and AM (OCE-1136477). This agency had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Salisbury J, Vandemark D, Campbell J, Hunt C, Wisser D, Reul N, et al. Spatial and temporal coherence between Amazon River discharge, salinity, and light absorption by colored organic carbon in western tropical Atlantic surface waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans (1978–2012). 2011;116(C7). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coles VJ, Brooks MT, Hopkins J, Stukel MR, Yager PL, Hood RR. The pathways and properties of the Amazon River Plume in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2013;118(12):6894–913. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molleri GS, Novo EMdM, Kampel M. Space-time variability of the Amazon River plume based on satellite ocean color. Cont Shelf Res. 2010;30(3):342–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramaniam A, Yager PL, Carpenter EJ, Mahaffey C, Bjorkman K, Cooley S, et al. Amazon River enhances diazotrophy and carbon sequestration in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(30):10460–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goes JI, Gomes HdR, Chekalyuk AM, Carpenter EJ, Montoya JP, Coles VJ, et al. Influence of the Amazon River discharge on the biogeography of phytoplankton communities in the western tropical north Atlantic. Progress in Oceanography. 2014;120:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith WO Jr, Demaster DJ. Phytoplankton biomass and productivity in the Amazon River plume: correlation with seasonal river discharge. Cont Shelf Res. 1996;16(3):291–319. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster RA, Kuypers MM, Vagner T, Paerl RW, Musat N, Zehr JP. Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom–cyanobacterial symbioses. The ISME journal. 2011;5(9):1484–93. 10.1038/ismej.2011.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster R, O’Mullan G. Nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying symbioses in the marine environment Nitrogen in the marine environment, 2nd ed Elsevier Science; 2008:1197–218. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mague T, Weare N, Holm-Hansen O. Nitrogen fixation in the north Pacific Ocean. Marine Biology. 1974;24(2):109–19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster RA, Subramaniam A, Zehr JP. Distribution and activity of diazotrophs in the Eastern Equatorial Atlantic. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11(4):741–50. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01796.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bombar D, Moisander PH, Dippner JW, Foster RA, Voss M, Karfeld B, et al. Distribution of diazotrophic microorganisms and nifH gene expression in the Mekong River plume during intermonsoon. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2011;424:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villareal T, Carpenter E. Buoyancy regulation and the potential for vertical migration in the oceanic cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Microb Ecol. 2003;45(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poretsky RS, Bano N, Buchan A, LeCleir G, Kleikemper J, Pickering M, et al. Analysis of microbial gene transcripts in environmental samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(7):4121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toseland A, Daines SJ, Clark JR, Kirkham A, Strauss J, Uhlig C, et al. The impact of temperature on marine phytoplankton resource allocation and metabolism. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3(11):979–984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivers AR, Sharma S, Tringe SG, Martin J, Joye SB, Moran MA. Transcriptional response of bathypelagic marine bacterioplankton to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The ISME journal. 2013;7(12):2315–29 10.1038/ismej.2013.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satinsky BM, Crump BC, Smith CB, Sharma S, Zielinski BL, Doherty M, et al. Microspatial gene expression patterns in the Amazon River Plume. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014:201402782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakraborty S, Lohrenz SE. Phytoplankton community structure in the river-influenced continental margin of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2015;521:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dortch Q, Whitledge TE. Does nitrogen or silicon limit phytoplankton production in the Mississippi River plume and nearby regions? Cont Shelf Res. 1992;12(11):1293–309. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickey BM, Kudela RM, Nash J, Bruland KW, Peterson WT, MacCready P, et al. River influences on shelf ecosystems: introduction and synthesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans (1978–2012). 2010;115(C2). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilton JA, Satinsky BM, Doherty M, Zielinski B, Zehr JP. Metatranscriptomics of N2-fixing cyanobacteria in the Amazon River plume. The ISME journal. 2014;9(7):1557–69. 10.1038/ismej.2014.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.John DE, Wang ZHA, Liu XW, Byrne RH, Corredor JE, Lopez JM, et al. Phytoplankton carbon fixation gene (RuBisCO) transcripts and air-sea CO2 flux in the Mississippi River plume. Isme J. 2007;1:517–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stukel MR, Coles VJ, Brroks MT, Hood RR. Top-down, bottom-up and physical controls on diatom-diazotroph assemblage growth in the Amazon River plume. Biogeosciences. 2014;11(12):3259. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satinsky BM, Zielinski BL, Doherty M, Smith CB, Sharma S, Paul JH, et al. The Amazon continuum dataset: quantitative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic inventories of the Amazon River plume, June 2010. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8(3):186–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falgueras J, Lara AJ, Fernández-Pozo N, Cantón FR, Pérez-Trabado G, Claros MG. SeqTrim: a high-throughput pipeline for pre-processing any type of sequence read. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(22):2933–5. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology. 1990;215(3):403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(Database issue):D590–6. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution. 2013;30(4):772–80. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1189–91. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–13. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds OR, Moret BM, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Journal of computational biology: a journal of computational molecular cell biology. 2010;17(3):337–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsen FA, Kodner RB, Armbrust EV. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11:538 10.1186/1471-2105-11-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eddy SR. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7(10):e1002195 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35(Database issue):D61–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whelan S, Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Molecular biology and evolution. 2001;18(5):691–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS one. 2010;5(3):e9490 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. Multiple Comparisons of Log-Likelihoods with Applications to Phylogenetic Inference. Molecular biology and evolution. 1999;16(8):1114. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeung LY, Berelson WM, Young ED, Prokopenko MG, Rollins N, Coles VJ, et al. Impact of diatom‐diazotroph associations on carbon export in the Amazon River plume. Geophysical Research Letters. 2012;39(18). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stukel M, Coles V, Brooks M, Hood R. Top-down, bottom-up and physical controls on diatom-diazotroph assemblage growth in the Amazon River Plume. Biogeosciences Discussions. 2013;10(8). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carpenter EJ, Subramaniam A, Capone DG. Biomass and primary productivity of the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium spp. in the tropical North Atlantic ocean. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 2004;51(2):173–203. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gifford SM, Sharma S, Rinta-Kanto JM, Moran MA. Quantitative analysis of a deeply sequenced marine microbial metatranscriptome. ISME J. 2011;5(3):461–72. 10.1038/ismej.2010.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rapaport F, Khanin R, Liang Y, Pirun M, Krek A, Zumbo P, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of differential gene expression analysis methods for RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2013;14(9):R95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu F, Massana R, Not F, Marie D, Vaulot D. Mapping of picoeucaryotes in marine ecosystems with quantitative PCR of the 18S rRNA gene. Fems Microbiol Ecol. 2005;52(1):79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang L, Jian W, Song X, Huang X, Liu S, Qian P, et al. Species diversity and distribution for phytoplankton of the Pearl River estuary during rainy and dry seasons. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2004;49(7):588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaeffer BA, Kurtz JC, Hein MK. Phytoplankton community composition in nearshore coastal waters of Louisiana. Marine pollution bulletin. 2012;64(8):1705–12. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chew L-L, Chong V. Copepod community structure and abundance in a tropical mangrove estuary, with comparisons to coastal waters. Hydrobiologia. 2011;666(1):127–43. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dagg MJ, Whitledge TE. Concentrations of copepod nauplii associated with the nutrient-rich plume of the Mississippi River. Cont Shelf Res. 1991;11(11):1409–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayes R, Kudla J, Gruissem W. Degrading chloroplast mRNA: the role of polyadenylation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1999;24(5):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tabita FR, Satagopan S, Hanson TE, Kreel NE, Scott SS. Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. Journal of experimental botany. 2008;59(7):1515–24. 10.1093/jxb/erm361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouchard JN, Roy S, Campbell DA. UVB Effects on the Photosystem II-D1 Protein of Phytoplankton and Natural Phytoplankton Communities. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2006;82(4):936–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Del Vecchio R, Subramaniam A. Influence of the Amazon River on the surface optical properties of the western tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans (1978–2012). 2004;109(C11). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medeiros PM, Seidel M, Ward ND, Carpenter EJ, Gomes HR, Niggemann J, et al. Fate of the Amazon River dissolved organic matter in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem Cy. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moroney J, Bartlett S, Samuelsson G. Carbonic anhydrases in plants and algae. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2001;24(2):141–53. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts K, Granum E, Leegood RC, Raven JA. Carbon acquisition by diatoms. Photosynth Res. 2007;93(1–3):79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dortch Q. The interaction between ammonium and nitrate uptake in phytoplankton. Marine ecology progress series Oldendorf. 1990;61(1):183–201. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hildebrand M. Cloning and functional characterization of ammonium transporters from the marine diatom Cylindrotheca fusiformis (Bacillariophyceae). J Phycol. 2005;41(1):105–13. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ward B, Voss M, Bange HW, Dippner JW, Middelburg JJ, Montoya JP. The marine nitrogen cycle: recent discoveries, uncertainties. 2013;368:p.20130121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hilton JA, Foster RA, Tripp HJ, Carter BJ, Zehr JP, Villareal TA. Genomic deletions disrupt nitrogen metabolism pathways of a cyanobacterial diatom symbiont. Nature communications. 2013;4:1767 10.1038/ncomms2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muchhal US, Pardo JM, Raghothama K. Phosphate transporters from the higher plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93(19):10519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hooley P, Whitehead MP, Brown MR. Eukaryote polyphosphate kinases: is the ‘Kornberg’complex ubiquitous? Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2008;33(12):577–82. 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pick U, Weiss M. Polyphosphate hydrolysis within acidic vacuoles in response to amine-induced alkaline stress in the halotolerant alga Dunaliella salina. Plant Physiol. 1991;97(3):1234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hildebrand M, Dahlin K, Volcani B. Characterization of a silicon transporter gene family in Cylindrotheca fusiformis: sequences, expression analysis, and identification of homologs in other diatoms. Molecular and General Genetics MGG. 1998;260(5):480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLachlan J, Craigie J. Chitan fibres in Cyclotella cryptica and growth of C. cryptica and Thalassiosira fluviatilis. Some Contemporary Studies in Marine Science. 1966:511–17. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Armbrust EV, Berges JA, Bowler C, Green BR, Martinez D, Putnam NH, et al. The Genome of the Diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: Ecology, Evolution, and Metabolism. Science. 2004;306(5693):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Round FE, Crawford RM, Mann DG. The diatoms: biology & morphology of the genera: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 67.McLachlan J, McInnes A, Falk M. Studies on the chitan (Chitin: Poly-N-Acetylglucosamine) fibers of the diatom Thalassiosira fluviatilis hustedt: Production and isolation of chitan fibers. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1965;43(6):707–13. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Durkin CA, Mock T, Armbrust EV. Chitin in diatoms and its association with the cell wall. Eukaryotic cell. 2009;8(7):1038–50. 10.1128/EC.00079-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Armbrust EV, Berges JA, Bowler C, Green BR, Martinez D, Putnam NH, et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science. 2004;306(5693):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The dotted line represents the 1:1 line of identity. The 186 data points represent the 31 genes measured at 6 stations. The average difference between replicate transcripts was 11.43%.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

Nuclear small subunit 18S rDNA maximum likelihood tree with the placement of environmental sequences. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized taxonomic abundances.

(TIF)

A maximum likelihood tree was used with the placement of metatranscriptomic predicted open-reading frames. Bootstrap support values ≥ 50% are shown. Circle sizes are proportion to the normalized expression levels. Branch lengths are log10-transformed.

(TIF)

Compiled data of all the sequences obtained and analyzed at the six stations. Duplicate samples were pooled to account for variations in the data that may occur from only taking one sample.

(TIF)

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

Sequences are available from the iMicrobe (data.imicrobe.us) database under project number CAM_P_0001194. The sequences are quality controlled fasta files of joined paired-end reads following removal of rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only). Sequences are also available from NCBI under accession numbers [SRP039390] (metagenomes) and [SRP039544] (poly(A)-selected metatranscriptomes). The NCBI sequences are fastq files from which rRNA sequences (metatranscriptomes only) have been removed prior to deposition. Environmental data (temperature, salinity, beam transmittance, dissolved oxygen, pCO2, etc.) have been previously published (references 2, 23), as have nutrient and community structure data corresponding to the stations examined (references 5, 23, 39, 40). The abundances of the diazotroph population was determined by epifluorescence microscopy as previously described (reference 41). ANACONDAS and ROCA project data are also available at the BCO-DMO data repository (http://www.bco-dmo.org/project/2097).