Abstract

Purpose

Related donor haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation (Haplo-HCT) using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) is increasingly used in patients lacking HLA-matched sibling donors (MSD). We compared outcomes after Haplo-HCT using PT-Cy with MSD-HCT in patients with lymphoma, using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research registry.

Materials and Methods

We evaluated 987 adult patients undergoing either Haplo-HCT (n = 180) or MSD-HCT (n = 807) following reduced-intensity conditioning regimens. The haploidentical group received graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis with PT-Cy with or without a calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate. The MSD group received calcineurin inhibitor–based GVHD prophylaxis.

Results

Median follow-up of survivors was 3 years. The 28-day neutrophil recovery was similar in the two groups (95% v 97%; P = .31). The 28-day platelet recovery was delayed in the haploidentical group compared with the MSD group (63% v 91%; P = .001). Cumulative incidence of grade II to IV acute GVHD at day 100 was similar between the two groups (27% v 25%; P = .84). Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 1 year was significantly lower after Haplo-HCT (12% v 45%; P < .001), and this benefit was confirmed on multivariate analysis (relative risk, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.31; P < .001). For Haplo-HCT v MSD-HCT, 3-year rates of nonrelapse mortality (15% v 13%; P = .41), relapse/progression (37% v 40%; P = .51), progression-free survival (48% v 48%; P = .96), and overall survival (61% v 62%; P = .82) were similar. Multivariate analysis showed no significant difference between Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT in terms of nonrelapse mortality (P = .06), progression/relapse (P = .10), progression-free survival (P = .83), and overall survival (P = .34).

Conclusion

Haplo-HCT with PT-Cy provides survival outcomes comparable to MSD-HCT, with a significantly lower risk of chronic GVHD.

INTRODUCTION

Despite remarkable advances in lymphoma therapeutics, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) remains the only potentially curative treatment for patients with high-risk relapsed or refractory lymphomas, including Hodgkin and aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) failing a prior autograft.1-4 However, the inability to identify an HLA-matched sibling donor (MSD) and sometimes the prohibitive delays in matched unrelated donor (URD) availability have been major barriers.5,6 Nearly all patients have an available related HLA-haploidentical donor (ie, a donor with whom they share a single HLA haplotype). Historically, attempts to perform T-cell–replete allografts from haploidentical donors were associated with unacceptable rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), nonrelapse mortality (NRM), and graft rejection.7-9

However, contemporary GVHD prophylactic approaches, especially post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy), have reduced the morbidity of T-cell–replete haploidentical HCT (Haplo-HCT).10 PT-Cy promotes immune tolerance by depleting rapidly proliferating alloreactive host and donor T cells, while sparing nonalloreactive memory T cells, regulatory T cells, and hematopoietic progenitor cells.11 Although single-institution studies12,13 have shown encouraging results of Haplo-HCT with PT-Cy in lymphoma, and although a recent registry analysis has reported comparable outcomes of Haplo-HCT versus matched URD allo-HCT in patients with lymphoma,14 it remains unclear whether the greater degree of HLA disparity associated with haploidentical allografts results in higher NRM and inferior survival when compared with MSD-HCT, the established standard for allo-HCT. To address this question, we compared the outcomes of Haplo-HCT against MSD-HCT in patients with lymphoma, using the observational database of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Included in this analysis are adult (18 years or older) patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and NHL undergoing their first reduced-intensity or nonmyeloablative conditioning (RIC/NMA) allo-HCT between 2008 and 2013. Eligible donors included either an MSD or a haploidentical related donor (mismatched for at least two or more HLA loci). Recipients of Haplo-HCT were limited to those receiving GVHD prophylaxis with PT-Cy (with or without a calcineurin inhibitor [CNI] and mycophenolate mofetil). GVHD prophylaxis in the MSD-HCT group was limited to CNI-based approaches. Patients receiving ex vivo or in vivo graft manipulation (T-cell–depleted or CD34 selected grafts) or those undergoing a planned tandem autologous–allo-HCT were excluded (Data Supplement).

Definitions

The intensity of conditioning regimens was determined using consensus criteria.15 Complete remission (CR) before HCT was defined as complete resolution of all known areas of disease on radiographic assessments, whereas partial remission (PR) was defined as ≥ 50% reduction in the greatest diameter of all sites of known disease and no new sites of disease. Resistant disease was defined as < 50% reduction in the diameter of all disease sites or development of new disease sites. Disease risk index (DRI) was defined as reported previously.16

Study End Points

The primary end point was overall survival (OS); death from any cause was considered an event, and surviving patients were censored at last contact. NRM was defined as death without evidence of lymphoma relapse/progression; relapse was considered a competing risk. Progression/relapse was defined as progressive lymphoma after HCT or lymphoma recurrence after a CR; NRM was considered a competing risk. For progression-free survival (PFS), a patient was considered to have treatment failure at the time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. Patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. Acute GVHD17 and chronic GVHD were graded as previously described.18,19 Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 successive days with absolute neutrophil count ≥ 500/µL after post-transplantation nadir. Platelet recovery was defined as achieving platelet counts ≥ 20,000/µL for at least 3 consecutive days, unsupported by transfusion for the preceding 7 days. For neutrophil and platelet recovery, death without the event was considered a competing risk.

Statistical Analysis

The Haplo-HCT cohort was compared with an MSD-HCT group. Probabilities of PFS and OS were calculated as described previously.20 Cumulative incidence of NRM, lymphoma progression/relapse, and hematopoietic recovery were calculated to accommodate for competing risks.21 Associations among patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related variables and outcomes of interest were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Backward elimination was used to identify covariates that influenced outcomes. Covariates with a P < .05 were considered significant. The proportional hazards assumption for Cox regression was tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each risk factor and each outcome. Covariates violating the proportional hazards assumption were added as time-dependent covariates in the Cox regression model. Interactions between the main effect and significant covariates were examined. Center effect was examined using the random effect score test22 for OS, PFS, relapse, and NRM. Results are expressed as relative risks (RR). The variables considered in multivariate analysis (MVA) are shown in the Data Supplement. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline patient-, disease- and transplantation-related characteristics of the 987 patients receiving MSD-HCT (n = 807) or Haplo-HCT (n = 180) are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the MSD-HCT and Haplo-HCT cohorts in terms of sex, number of prior therapy lines, bone marrow or extranodal involvement at HCT, presence of bulky disease, HCT comorbidity index, chemotherapy sensitivity at HCT, and interval between diagnosis and allo-HCT. Compared with the MSD cohort, the Haplo-HCT group included a higher proportion of patients with advanced age (age ≥ 60 years, 24% v 35%; P < .001), African American ethnicity (4% v 15%; P < .001), and Karnofsky performance score (KPS) ≥ 90 (68% v 79%; P < .001). Although the proportion of patients with stage III and IV disease at diagnosis was higher in the MSD cohort (67% v 47%; P = .001), at the time of allo-HCT, significantly more Haplo-HCT cohort patients had intermediate or high DRI (75% v 63%; P < .001). The most common lymphoma histology in the Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT groups was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma (FL), respectively. All patients undergoing Haplo-HCT received conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and 200 cGy total body irradiation (TBI), whereas those in the MSD-HCT group received conditioning with fludarabine plus either an alkylator and/or 200-cGy TBI. The graft source was an unmanipulated bone marrow (BM) in 93% of Haplo-HCT and peripheral blood (PB) in 98% of MSD-HCT.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Lymphoma Reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research From 2008 to 2013

| Variable | Haploidentical Donors | HLA-Identical Siblings | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 180 | 807 | |

| No. of centersa | 21 | 112 | |

| No. of CRF-level data patients | 51 | 104 | |

| Age at HCT, median (range), years | 55 (18-75) | 54 (18-77) | < .001 |

| 18-30 | 22 (12) | 72 (9) | |

| 31-40 | 20 (11) | 98 (12) | |

| 41-50 | 24 (13) | 136 (17) | |

| 51-60 | 51 (28) | 309 (38) | |

| 61-70 | 51 (28) | 184 (23) | |

| > 70 | 12 (7) | 8 (< 1) | |

| Male sex | 115 (64) | 496 (61) | .54 |

| Race | < .001 | ||

| White | 146 (81) | 689 (85) | |

| Black | 27 (15) | 36 (4) | |

| Otherb | 6 (3) | 29 (4) | |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 53 (7) | |

| Karnofsky performance score ≥ 90 | 142 (79) | 548 (68) | < .001 |

| HCT comorbidity index | .008 | ||

| 0 | 77 (43) | 327 (41) | |

| 1-2 | 50 (27) | 195 (24) | |

| ≥ 3 | 53 (29) | 236 (29) | |

| Missing | 0 | 49 (6) | |

| Histology | .002 | ||

| Follicular lymphomac | 28 (16) | 204 (25) | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphomad | 65 (36) | 189 (23) | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 21 (12) | 113 (14) | |

| Mature T- and NK-cell lymphomas | 22 (12) | 123 (15) | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 44 (24) | 178 (22) | |

| Advanced stage (III/IV) at diagnosis | 23 (47) | 70 (67) | .001 |

| Interval from diagnosis to HCT, months | .12 | ||

| Median (range) | 31 (< 1-255) | 34 (1-386) | |

| Elevated lactate dehydrogenase at HCT | 16 (31) | 26 (25) | .007 |

| Unknown | 14 (27) | 11 (11) | |

| Bulky disease (> 5 cm) at HCT | 5 (10) | 8 (8) | .86 |

| Bone marrow involved at HCT | 6 (12) | 6 (6) | .31 |

| Active extranodal involvement at HCT | 18 (35) | 26 (25) | .28 |

| Lines of prior therapies, median (range) | 3 (1-7) | 3 (1-9) | .10 |

| Radiation therapy before HCT | 12 (24) | 23 (22) | .03 |

| Missing | 8 (16) | 4 (4) | |

| Remission status at HCT | .08 | ||

| Complete remission | 70 (39) | 327 (41) | |

| Partial remission | 97 (54) | 366 (45) | |

| Chemotherapy-refractory | 10 (6) | 98 (12) | |

| Untreated | 2 (1) | 9 (1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | |

| Disease risk index at HCT | < .001 | ||

| Low | 45 (25) | 302 (37) | |

| Intermediate | 122 (68) | 417 (52) | |

| High | 12 (7) | 88 (11) | |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 | |

| History of prior autologous HCT | 69 (38) | 397 (49) | .008 |

| Conditioning regimen | < .001 | ||

| Flu/Bu | 0 | 221 (27) | |

| Flu/Cy with or without rituximab | 0 | 204 (25) | |

| Flu/Cy/200 cGy TBI | 180 | 34 (4) | |

| Flu/Mel with or without rituximab | 0 | 237 (29) | |

| Flu/200 cGy TBI with or without rituximab | 0 | 111 (14) | |

| TBI in conditioning | 180 | 145 (18) | < .001 |

| Graft type | < .001 | ||

| Bone marrow | 168 (93) | 15 (2) | |

| Peripheral blood | 12 (7) | 792 (98) | |

| Female donor to male recipient | 50 (28) | 224 (28) | .76 |

| Donor/recipient CMV status | .001 | ||

| −/+ | 39 (22) | 162 (20) | |

| Other | 140 (77) | 629 (78) | |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 16 (2) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | < .001 | ||

| Post-transplant Cyf | 180 (100) | 0 | |

| CNI + MMF with or without othersg | 0 | 247 (31) | |

| CNI + MTX with or without others (except MMF)h | 0 | 444 (55) | |

| CNI ± others (except MMF/MTX)i | 0 | 116 (14) | |

| Follow-up of survivors, median (range), months | 37 (6-73) | 36 (3-76) |

NOTE. Italicized text indicates variables available in CRF-level data patients.

Abbreviations: Bu, busulfan; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; CRF, comprehensive report form; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; Mel, melphalan; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MSD, HLA-matched sibling donor; MTX, methotrexate; NK, natural killer; PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified; TBI, total body irradiation; URD, unrelated donor.

Twenty centers reported performing both haploidentical and HLA-identical sibling HCT. Ninety-two centers only reported HLA-identical sibling HCTs. Only one center reported only haploidentical HCT. This center contributed only one haploidentical HCT case.

Haploidentical: Asian (n = 5), Native American (n = 1). HLA-identical siblings: Asian (n = 24), Pacific Islander (n = 2), Native American (n = 3).

In the haploidentical versus HLA-identical sibling groups, the proportion of patients with grade 1 and 2 follicular lymphoma was 15 (54%) versus 143 (70%); grade 3 follicular lymphoma was eight (28%) versus 37 (18%), and unknown grade 5 (18%) versus 24 (12%), respectively (overall P = .33).

Transformed from indolent lymphoma: haploidentical group: n = 5, HLA-identical siblings: n = 8.

Details of mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms included in the analysis. For haploidentical group: PTCL-NOS = 7, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma = 3, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma = 4, anaplastic large cell lymphoma = 3, others = 5. For MSD group: PTCL-NOS = 42, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma = 24, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma = 11, anaplastic large cell lymphoma = 20, others = 26.

CNI/MMF/Cy (n = 172), Cy alone (n = 3), Cy/CNI (n = 4), MMF/Cy (n = 1).

CNI/MMF (n = 240), CNI/MMF/MTX (n = 7).

CNI/MTX/steroids (n = 8), CNI/MTX (n = 380), CNI/MTX/sirolimus (n = 56).

CNI/sirolimus (n = 95), CNI alone (n = 21).

Hematopoietic Recovery

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at day 28 in Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT groups was 95% versus 97%, respectively (P = .31; Table 2). The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery in Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT groups at day 28 and day 100 was 63% versus 91% (P < .001) and 94% versus 96% (P = .33), respectively.

Table 2.

Hematopoietic Recovery, GVHD, and Unadjusted Survival Outcomes

| Outcome | Haploidentical | HLA-Identical Siblings | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Evaluated | Probability (95% CI; %) | No. Evaluated | Probability (95% CI; %) | ||

| Neutrophil recovery > 500/uL | 179 | 803 | |||

| 28-day | 95 (90 to 98) | 97 (95 to 98) | .31 | ||

| 100-day | 99 (98 to 100) | 98 (97 to 99) | .07 | ||

| Platelet recovery ≥ 20/uL | 180 | 778 | |||

| 28-day | 63 (56 to 70) | 91 (89 to 93) | < .001 | ||

| 100-day | 94 (90 to 97) | 96 (94 to 97) | .33 | ||

| Acute GVHD (II-IV)* | 49 | 104 | |||

| 100-day | 27 (15 to 40) | 25 (17 to 34) | .84 | ||

| Acute GVHD (III-IV)* | 49 | 104 | |||

| 100-day | 8 (2 to 17) | 8 (3 to 14) | .92 | ||

| Acute GVHD (II-IV) | 175 | 789 | |||

| 180-day | 51 (43 to 60) | 44 (40 to 49) | .15 | ||

| Acute GVHD (III and IV) | 175 | 789 | |||

| 180-day | 10 (5 to 17) | 18 (15 to 21) | .03 | ||

| Chronic GVHD | 178 | 767 | |||

| 6-month | 5 (2 to 9) | 24 (21 to 27) | < .001 | ||

| 1-year | 12 (8 to 18) | 45 (41 to 48) | < .001 | ||

| 2-year | 15 (10 to 21) | 52 (49 to 56) | < .001 | ||

| Mild chronic GVHD | 47 | 99 | |||

| 6-month | 6 (1 to 15) | 5 (2 to 11) | .77 | ||

| 1-year | 13 (5 to 24) | 17 (10 to 25) | .56 | ||

| 2-year | 13 (5 to 24) | 20 (13 to 29) | .27 | ||

| Moderate/severe chronic GVHD | 47 | 99 | |||

| 6-month | 2 (0 to 9) | 13 (7 to 20) | .01 | ||

| 1-year | 2 (0 to 9) | 26 (18 to 36) | < .001 | ||

| 2-year | 2 (0 to 9) | 33 (24 to 43) | < .001 | ||

| Nonrelapse mortality | 180 | 804 | |||

| 1-year | 10 (6 to 15) | 9 (7 to 11) | .57 | ||

| 2-year | 14 (10 to 20) | 11 (9 to 14) | .27 | ||

| 3-year | 15 (10 to 21) | 13 (10 to 15) | .41 | ||

| Relapse/progression | 180 | 804 | |||

| 1-year | 31 (25 to 38) | 30 (27 to 33) | .78 | ||

| 2-year | 35 (28 to 42) | 37 (34 to 41) | .61 | ||

| 3-year | 37 (30 to 44) | 40 (36 to 43) | .51 | ||

| Progression-free survival | 180 | 804 | |||

| 1-year | 59 (51 to 66) | 61 (58 to 64) | .55 | ||

| 2-year | 51 (43 to 58) | 52 (48 to 55) | .78 | ||

| 3-year | 48 (40 to 56) | 48 (44 to 51) | .96 | ||

| Overall survival | 180 | 807 | |||

| 1-year | 77 (70 to 82) | 78 (75 to 81) | .64 | ||

| 2-year | 65 (57 to 72) | 68 (65 to 72) | .39 | ||

| 3-year | 61 (54 to 69) | 62 (59 to 66) | .82 | ||

NOTE. Probabilities of neutrophil and platelet recovery, platelet recovery, acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, treatment-related mortality, and progression/relapse were calculated using the cumulative incidence estimate. Progression-free survival and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimate.

Abbreviations: GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Calculated from comprehensive report form–level data only.

The median day 100 donor-cell chimerism in haplo-HCT versus MSD cohorts on unsorted assays was 100% (range, 77 to 100) versus 99% (range, 28 to 100; P = .002). The respective values for myeloid-cell–specific assays were 100% (range, 0 to 100) versus 99% (range, 13 to 100; P = .41), whereas those for T-cell–specific assay were 100% (range, 0 to 100) versus 94% (range, 15 to 100; P < .001). The proportion of patients achieving complete donor-cell chimerism (ie, ≥ 95% donor cells) by day 100 in haplo-HCT versus MSD cohorts on unsorted, myeloid-cell–specific and T-cell–specific assays was 94% versus 66% (P = .003), 80% versus 58% (P = .35), and 95% versus 48% (P = .001), respectively.

GVHD

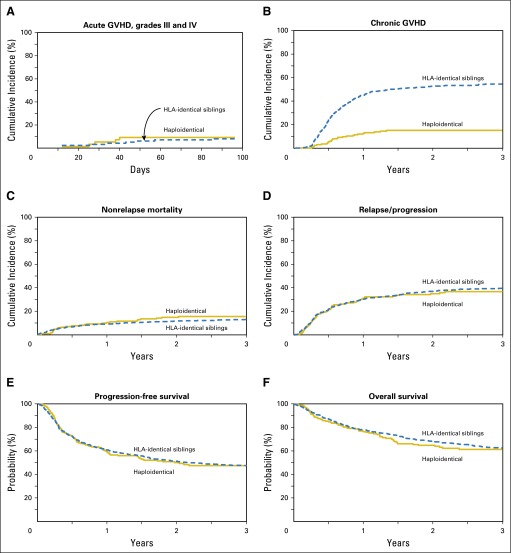

The cumulative incidence of grade II to IV acute GVHD at day 100 (Table 2) in the Haplo-HCT cohort was 27% (95% CI, 15 to 40), compared with 25% (95% CI, 17 to 34) in the MSD group (P = .84). The rates of grades III and IV acute GVHD at day 100 were 8% in both groups (Table 2; Fig 1A). On MVA, there was no significant difference in the risk of grade II to IV and grade III and IV acute GVHD between the two groups (Table 3).

Fig 1.

(A) Cumulative incidence of grade III and IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. (B) Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. (C) Cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. (D) Cumulative incidence of lymphoma relapse/progression in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. (E) Progression-free survival in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. (F) Overall survival in recipients of haploidentical donor versus HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Table 3.

Results of Multivariate Analysis for Outcomes After Haplo-HCT or MSD-HCT

| Outcome | No. | RR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Grade II-IV acute GVHD* | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 789 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 175 | 1.40 | 0.99 | 1.99 | .06 |

| Grade III and IV acute GVHD* | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 789 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 175 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.98 | .45 |

| Chronic GVHD | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 712 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 177 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.31 | < .001 |

| Moderate/severe chronic GVHD | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 99 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 47 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.42 | .005 |

| Nonrelapse mortality | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 755 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 180 | 1.52 | 0.99 | 2.34 | .06 |

| Progression/relapse | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 804 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 180 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 1.04 | .10 |

| Progression-free survival | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 804 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 180 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 1.23 | .83 |

| Overall survival | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings | 807 | 1 | |||

| Haploidentical | 180 | 1.14 | 0.87 | 1.49 | .34 |

Abbreviations: GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; MSD, HLA-matched sibling donor; RR, relative risk; URD, unrelated donor.

Acute GVHD models used logistic regression.

The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 1 year (Table 2; Fig 1B) after Haplo-HCT was 12% (95% CI, 8 to 18) compared with 45% (95% CI, 41 to 48) in the MSD cohort (P < .001). MVA showed a significantly reduced risk of any chronic GVHD (RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.31; P < .001), as well as moderate/severe chronic GVHD (RR, 0.06; P = .005) after Haplo-HCT relative to MSD-HCT (Table 3).

NRM and Relapse

Among recipients of Haplo-HCT, 1-year NRM was 10% (95% CI, 6 to 15) compared with 9% (95% CI, 7 to 11) in MSD allografts (P = .57; Table 2; Fig 1C). On MVA, compared with MSD-HCT, there was no significant difference in the risk of NRM with Haplo-HCT (RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.99 to 2.34; P = .06; Table 3). Independent of the transplant type, KPS < 90 (RR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.4 to 3.05; P = .002) and HCT comorbidity index ≥ 3 (RR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.22 to 2.90; P = .004) were associated with higher risk of NRM (Data Supplement).

The cumulative incidence of disease progression/relapse at 3 years was 37% (95% CI, 30 to 44) and 40% (95% CI, 36 to 43) in the haploidentical and MSD groups, respectively (P = .51; Table 2; Fig 1D). On MVA, relative to the MSD-HCT group, there was no significant difference in the risk of progression/relapse after Haplo-HCT (RR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.04; P = .10; Table 3). Other factors associated with higher risk of disease progression/relapse were lymphoma histology other than FL, not being in CR at allo-HCT, presence of bulky or extranodal disease at HCT, HCT performed before 2010, and intermediate or high DRI (Data Supplement).

PFS and OS

With a median follow-up of 3 years for surviving patients, the 3-year PFS was not significantly different between the Haplo-HCT (48%; 95% CI, 40 to 56) and MSD-HCT (48%; 95% CI, 44 to 51) groups (P = .96; Table 2; Fig 1E), and this was confirmed by MVA (RR of treatment failure, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.23; P = .83; Table 3). Independent of the transplant type, other predictors of higher risk of therapy failure included lymphoma histology other than FL, KPS < 90, not being in CR at allo-HCT, presence of extranodal or bulky disease, HCT performed before 2010, and intermediate or high DRI (Data Supplement).

The 3-year OS was not significantly different in the Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT groups at 61% (95% CI, 54 to 69) and 62% (95% CI, 59 to 66), respectively (P = .82; Table 2; Fig 1F), and this was confirmed by MVA (RR of mortality, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.49; P = .34; Table 3). Independent of the transplant type, other predictors of higher risk of mortality included lymphoma histology other than FL or T-cell NHL, KPS < 90, not being in CR at allo-HCT, presence of bulky disease, HCT performed before 2010, and intermediate or high DRI (Data Supplement). PFS and OS stratified according to lymphoma histologies are provided in the Data Supplement.

Causes of Death

The most common cause of death in both cohorts was recurrent/progressive lymphoma: 47% (n = 34) and 52% (n = 151) in the Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT groups, respectively (Data Supplement). Although GVHD was the cause of death in 5% (n = 13) of MSD-HCT recipients, only one death in the haploidentical group was attributed to this.

Center Effect

Haplo-HCT was performed at 21 transplant centers compared with 112 centers performing MSD-HCT. To ensure that outcomes reported in the current analysis were not driven by institutional expertise, transplant center effect was examined. We found no center effect on the hazard of OS (P = .06) and PFS (P = .15), and the cause-specific hazard of relapse (P = .77) and NRM (P = .24), using the random effect score test (Data Supplement).

Subset Analysis

Because the predominant graft source differed between the haploidentical and MSD cohorts, subset MVA of transplantation outcomes was performed in Haplo-HCT receiving BM grafts (n = 163) and MSD-HCT receiving PB grafts (n = 774). The results were in line with the outcomes of entire study population (Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

The success of allo-HCT has historically depended on grafts from donors matched with the recipient at the HLA loci with high-resolution techniques. Approximately 30% of patients have an HLA-matched sibling donor, and, in spite of millions of donors enrolled in transplant registries, HLA-matched URD availability is driven by ethnicity6 and varies widely across countries. The URD search process is also prone to logistical challenges, delays,23,24 and occasionally disease progression before transplantation, especially in aggressive malignancies.25 The use of haploidentical related donors can overcome these limitations, but in lymphoma no studies have compared this approach with the established gold standard donor source (ie, MSD-HCT). Here, we performed a registry analysis comparing outcomes of patients with lymphoma undergoing Haplo-HCT using PT-Cy–based GVHD prophylaxis with patients undergoing MSD-HCT. Our analysis suggests that survival, risk of relapse/progression, and NRM were virtually identical for Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT cohorts. Second, Haplo-HCT with PT-Cy was associated with significantly lower rates of chronic GVHD, and mortality secondary to GVHD was rare. Finally, nonengraftment was not a concern with similar neutrophil recovery kinetics in the Haplo-HCT and MSD-HCT cohorts.

The Haplo-HCT cohort in this study received uniform conditioning (fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/200-cGy TBI) and PT-Cy–based GVHD prophylaxis. To ensure a valid comparison, the eligibility in the MSD-HCT group was limited to conditioning with fludarabine plus an alkylator and/or 200 cGy TBI and GVHD prophylaxis to CNI-based approaches. Additional MVA restricted to the MSD-HCT cohort did not show any differences between individual conditioning and GVHD prophylactic regimens in terms of NRM, progression/relapse, therapy failure, and mortality risk (data not shown). This step ensured that survival outcomes among MSD-HCT recipients were not influenced by the heterogeneity of conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis approaches. Although more patients in the MSD group had chemorefractory disease and KPS < 90, significantly more patients undergoing Haplo-HCT had intermediate or high DRI, indicating that the Haplo-HCT cohort possibly had more biologically higher-risk patients. The DRI is a validated tool that stratifies patients into risk groups using type and status of disease at the time of transplantation.16,26 The delay in platelet recovery in the Haplo-HCT cohort is likely due to the application of PT-Cy and has been observed in other recent reports.27

The low incidence of chronic GVHD with Haplo-HCT using the PT-Cy platform in our analysis (12% at 1 year) is in line with published data.28 Although it is plausible that the low chronic GVHD rates observed with Haplo-HCT are in part due to the frequent use of BM as graft source in this cohort, it is important to point out that unlike myeloablative allografts, in the setting of RIC transplantation BM grafts have not been consistently shown to be associated with reduced chronic GVHD risk.29,30 Effective depletion of alloreactive donor T cells by PT-Cy along with the use of BM as the predominant graft source are likely major drivers of reduced chronic GVHD risk after Haplo-HCT in our study. However, the relative contribution of the graft source (BM v PB) and PT-Cy in reducing the risk of chronic GVHD cannot be dissected by the current analysis. The ongoing Novel Approaches for Graft-versus-Host Disease Prevention Compared to Contemporary Controls trial (BMT CTN 1203; NCT02208037) is evaluating the role of PT-Cy as GVHD prophylaxis in RIC allo-HCT recipients. On its completion, we may better understand the impact of the PT-Cy for GVHD prophylaxis relative to the standard CNI-based prophylaxis. Although our analysis did not examine quality of life and other correlates that translate the reduced chronic GVHD risk to patient-reported outcomes, such analyses are imperative given the impact of chronic GVHD on long-term survivorship and will need to be examined in the prospective setting. Despite lower chronic GVHD in the haploidentical cohort, the risk of relapse was not higher, suggesting that any graft-versus-lymphoma effects in the Haplo-HCT setting are similar to MSD-HCT and independent of clinical chronic GVHD. Data on the kinetics of post–allo-HCT immune reconstitution are not captured in the registry; however, there was no difference in terms of fatal infections between the two groups (Data Supplement).

To date, no large prospective or registry data are available to suggest that alternative donor HCT for hematologic malignancies in general and lymphoma in particular could provide outcomes comparable to MSD-HCT. Although survival and NRM rates after mismatched URD or cord blood allografts have in general been either inferior or comparable to those after matched URD,31,32 no large studies suggest that such alternative donor sources could provide outcomes comparable to MSD-HCT. The 3-year NRM and OS rates (15% and 61%, respectively) after Haplo-HCT in the current analysis not only compare favorably against prior Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research data33 for patients with lymphoma undergoing mismatched URD (3-year NRM, 44%; OS, 37%) or cord blood (3-year NRM, 37%; OS, 41%) allo-HCT, but these data for the first time demonstrate that RIC/NMA Haplo-HCT using the PT-Cy platform provides early post-HCT survival outcomes comparable to MSD-HCT, while significantly reducing the burden of chronic GVHD. It is important to note that the 3-year OS of NHL-only patients in our study (58%) seems higher than estimates reported by Kasamon et al12 (47% at 3 years). Possible reasons for this difference include older HCT era (2003 to 2013), exclusion of young patients, and inclusion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and aggressive lymphomas besides diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the prior publication.

Similar to other registry-based analyses, there are some caveats to be considered. Any observational study comparing different interventions is subject to preferences of the treating centers/physicians owing to the complex criteria for selection that underlie the choice of intervention. More frequent history of autografts in the MSD-HCT group could be reflective of institutional practice differences; however, the similar time interval between diagnosis and allo-HCT and median lines of prior therapies between the two groups suggest that no one group was overrepresented by lymphomas earlier in the disease course. Patients in this study had various histologies, and although outcomes reported here were adjusted for lymphoma subtypes, a potential benefit or lack thereof of one donor source over another for any specific lymphoma subtype cannot be confirmed. In addition, with the available data in the registry we cannot evaluate potential differences between the two cohorts in terms of health care cost effectiveness and resource use (eg secondary to infectious complications).

In summary, compared with RIC MSD-HCT, Haplo-HCT with PT-Cy significantly reduces the risk of chronic GVHD without compromising relapse and survival. RIC/NMA conditioning followed by Haplo-HCT with PT-Cy should be considered an acceptable option for patients with lymphoma without MSDs. As such, this strategy can broaden the timely applicability of allo-HCT without compromising efficacy and limit the racial barriers for receiving this potentially curative treatment option. Additional analyses in collaboration with European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation are being planned to validate these results in a larger international patient cohort. The results of our study warrant confirmation in prospective, randomized, controlled trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Morgan Geronime for administrative support and Mary Eapen for her valuable scientific input.

Footnotes

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute; contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration; two grants, N00014-13-1-0039 and N00014-14-1-0028, from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Allos Therapeutics, *Amgen, Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin, Ariad, Be the Match Foundation, *Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, *Celgene Corporation, Chimerix, Inc, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Fresenius-Biotech North America, *Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture, Genentech,*Gentium SpA, Genzyme Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, Health Research, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, HistoGenetics, Incyte Corporation, Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation, Kiadis Pharma, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Medac, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Merck & Co, Millennium: Takeda Oncology, *Milliman USA, *Miltenyi Biotec, National Marrow Donor Program, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Optum Healthcare Solutions, Osiris Therapeutics, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Perkin Elmer, *Remedy Informatics, *Sanofi US, Seattle Genetics, Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Soligenix, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics, Stemsoft Software, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, *Tarix Pharmaceuticals, *TerumoBCT, *Teva Neuroscience, *THERAKOS, University of Minnesota, University of Utah, and *Wellpoint. Asterisks denote corporate members.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration, or any other agency of the US Government.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Nilanjan Ghosh, Reem Karmali, Vanderson Rocha, Mehdi Hamadani

Collection and assembly of data: Nilanjan Ghosh, Reem Karmali, Vanderson Rocha, Kwang Woo Ahn, Alyssa DiGilio, Mehdi Hamadani

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Reduced-Intensity Transplantation for Lymphomas Using Haploidentical Related Donors Versus HLA-Matched Sibling Donors: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Nilanjan Ghosh

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, AbbVie

Reem Karmali

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pharmacyclics, Seattle Genetics

Speakers’ Bureau: Celgene

Vanderson Rocha

No relationship to disclose

Kwang Woo Ahn

No relationship to disclose

Alyssa DiGilio

No relationship to disclose

Parameswaran N. Hari

Stock or Other Ownership: Pharmacyclics

Honoraria: Celgene, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Amgen, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Onyx Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Veronika Bachanova

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seattle Genetics, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Novartis, Alopexx, Celgene

Ulrike Bacher

No relationship to disclose

Parastoo Dahi

No relationship to disclose

Marcos de Lima

No relationship to disclose

Anita D’Souza

No relationship to disclose

Timothy S. Fenske

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Sanofi

Siddhartha Ganguly

No relationship to disclose

Mohamed A. Kharfan-Dabaja

Honoraria: Incyte, Seattle Genetics, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Speakers’ Bureau: Incyte, Seattle Genetics, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Tim D. Prestidge

No relationship to disclose

Bipin N. Savani

No relationship to disclose

Sonali M. Smith

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Seattle Genetics, TG Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, Immunogenix, Pharmacyclics

Anna M. Sureda

No relationship to disclose

Edmund K. Waller

Leadership: Cambium Medical Technologies

Stock or Other Ownership: Cambium Medical Technologies

Honoraria: Novartis, Celldex Therapeutics, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Pharmaceutical Research Associates, Seattle Genetics, Mesoblast

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Celldex Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, Mesoblast

Research Funding: Novartis, Celldex

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Human fibrinogen-depleted platelet lysate

Samantha Jaglowski

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seattle Genetics

Research Funding: Pharmacyclics, Celldex, Novartis

Alex F. Herrera

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Pharmacyclics, Immune Design

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Philippe Armand

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Infinity Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck (Inst), Tensha Therapeutics (Inst), Sequenta (Inst), Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Rachel B. Salit

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Adaptive Biotechnologies

Nina D. Wagner-Johnston

Consulting or Advisory Role: Gilead Sciences, Pharmacyclics

Speakers’ Bureau: Gilead Sciences

Research Funding: Celgene

Ephraim Fuchs

No relationship to disclose

Javier Bolaños-Meade

No relationship to disclose

Mehdi Hamadani

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: MedImmune, Celerant

Research Funding: Takeda Pharmaceuticals

REFERENCES

- 1.Khouri IF, McLaughlin P, Saliba RM, et al. Eight-year experience with allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular lymphoma after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Blood. 2008;111:5530–5536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazarus HM, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al. A comparison of HLA-identical sibling allogeneic versus autologous transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A report from the CIBMTR. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16:35-45, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Peniket AJ, Ruiz de Elvira MC, Taghipour G, et al. An EBMT registry matched study of allogeneic stem cell transplants for lymphoma: Allogeneic transplantation is associated with a lower relapse rate but a higher procedure-related mortality rate than autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:667–678. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratanatharathorn V, Uberti J, Karanes C, et al. Prospective comparative trial of autologous versus allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1994;84:1050–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grewal SS, Barker JN, Davies SM, et al. Unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation: Marrow or umbilical cord blood? Blood. 2003;101:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:339–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1311707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beatty PG, Clift RA, Mickelson EM, et al. Marrow transplantation from related donors other than HLA-identical siblings. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:765–771. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanda Y, Chiba S, Hirai H, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from family members other than HLA-identical siblings over the last decade (1991-2000) Blood. 2003;102:1541–1547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szydlo R, Goldman JM, Klein JP, et al. Results of allogeneic bone marrow transplants for leukemia using donors other than HLA-identical siblings. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1767–1777. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Symons HJ, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 14:641-650, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Fuchs EJ. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for tolerance induction in HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:683–693. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasamon YL, Bolaños-Meade J, Prince GT, et al. Outcomes of nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical blood or marrow transplantation with high-dose post-transplantation cyclophosphamide in older adults. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3152–3161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raiola A, Dominietto A, Varaldo R, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical BMT following non-myeloablative conditioning and post-transplantation CY for advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:190–194. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanate AS, Mussetti A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Reduced-intensity transplantation for lymphomas using haploidentical related donors versus HLA-matched unrelated donors. Blood 127:938-947, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: Working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15:1628-1633, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Armand P, Kim HT, Logan BR, et al. Validation and refinement of the Disease Risk Index for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;123:3664–3671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man: A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Gilman A, et al. A survey of diagnosis, management, and grading of chronic GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8:32–39. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm11846354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Loberiza FR, Klein JP, et al. A SAS macro for estimation of direct adjusted survival curves based on a stratified Cox regression model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;88:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Zhang MJ. SAS macros for estimation of direct adjusted cumulative incidence curves under proportional subdistribution hazards models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;101:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Commenges D, Andersen PK. Score test of homogeneity for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1:145–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00985764. discussion 157-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kernan NA, Bartsch G, Ash RC, et al. Analysis of 462 transplantations from unrelated donors facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:593–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303043280901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGlave P, Bartsch G, Anasetti C, et al. Unrelated donor marrow transplantation therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia: Initial experience of the National Marrow Donor Program. Blood. 1993;81:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies SM, Ramsay NK, Weisdorf DJ. Feasibility and timing of unrelated donor identification for patients with ALL. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:737–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCurdy SR, Kanakry JA, Showel MM, et al. Risk-stratified outcomes of nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical BMT with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2015;125:3024–3031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-623991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bashey A, Zhang X, Jackson K, et al. Comparison of outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplants from T-replete haploidentical donors using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide with 10 of 10 HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 allele-matched unrelated donors and HLA-identical sibling donors: A multivariable analysis including Disease Risk Index. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22:125-133, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118:282–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eapen M, Logan BR, Horowitz MM, et al. Bone marrow or peripheral blood for reduced-intensity conditioning unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:364–369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagler A, Labopin M, Shimoni A, et al. Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as the stem cell source for unrelated donor allogeneic transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission: An analysis from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 18:1422-1429, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2265–2275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha V, Labopin M, Sanz G, et al. Transplants of umbilical-cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2276–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachanova V, Burns LJ, Wang T, et al. Alternative donors extend transplantation for patients with lymphoma who lack an HLA matched donor. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:197–203. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.