Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite recognized disparities in child health outcomes associated with sleep, the majority of research has been based on small, homogeneous samples. Using a nationally-representative sample of US children and adolescents, we examined trends and social determinants of inadequate sleep across age groups.

Study design

Comparison of cross-sectional studies.

Methods

Our study used the 2003 (n=68,418), 2007 (n=63,442), and 2011/12 (n=65,130) waves of the National Survey of Children’s Health, a nationally-representative survey of 6-17-year-olds. Parents reported whether the child had inadequate sleep (0-6 days of not getting enough sleep versus 7 days).

Results

From 2003 through 2011/12, inadequate sleep increased from 23 to 36% among 6-9-year-olds, 30 to 41% among 10-13-year-olds, and 41 to 49% among 14-17-year-olds. Among 10-17-year-olds, those from households with more than a high school degree were more likely to have inadequate sleep (adjusted ORs 1.19-1.22). Although for 10-13-year-olds there was a gradient in inadequate sleep across income (aOR 1.20-1.34), for 14-17-year-olds, only those from the two highest income levels were more likely to have inadequate sleep (aOR 1.28-1.37). Parent report that neighbors did not watch out for other’s children was associated with an increased risk for inadequate sleep across all ages (aORs 1.13-1.26).

Conclusions

Inadequate sleep occurred as young as age 6 years and increased with age, became more prevalent, and was socially patterned. In order to prevent inadequate sleep across the life course, surveillance and monitoring is needed across all age groups to identify critical periods for intervention

Keywords: sleep, adolescent, child, epidemiology, social determinants of health

Introduction

With mounting evidence on the detrimental effects of inadequate sleep on physical and mental health outcomes in children and adolescents,1-5 increasing the amount and quality of sleep have become public health priorities in the US. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention endorse recommendations by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute that school-aged children get at least 10 hours and adolescents get 9-10 hours of sleep daily.6 ‘Sleep Health’ is a new Healthy People 2020 topic with a target to increase the proportion of adolescents who get sufficient sleep, defined as 8 or more hours of sleep on an average school night, from 30.9% to 33.2%.7 As of 2013, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), a national school-based survey of US high school students, found that only 32% of students reported getting 8 or more hours of sleep during the school week and there was no significant change since 2007 when sleep data were first collected.8

Age is the most well-established determinant of sleep duration, with total sleep time decreasing from infancy through adulthood.9 However, the Healthy People 2020 target7 is for adolescents overall and sleep patterns may vary within the teenage years.10 While 40% of US students in 9th grade (approximately 14-15 years old) reported 8 or more hours of sleep on an average school night, this decreased to 23% of 12th grade students (approximately 17-18 years old).8 Furthermore, the sleep target does not include younger children and there are no national data for this age group using the same measurement of sleep.11 Thus, there is little known about the age that sleep issues may begin and whether the prevalence of sleep issues may be changing over time.

Despite recognized disparities in many of the health outcomes associated with sleep, such as obesity,12 the majority of research on sleep has been based on small sample sizes that are often homogenous in their socio-demographic composition. Only a few studies have examined the social determinants of sleep in children and adolescents. From 1991 through 2011, Knutson identified five studies that each examined socioeconomic and/or racial/ethnic differences in sleep.5 Together with other research, the overall patterns suggest that children from more disadvantaged circumstances have lower sleep quality and shorter duration than those from more advantaged backgrounds, while Black children have shorter sleep duration and nap more than white children.5, 13, 14 More recently, based on the YRBS data, Black high school students were less likely to report getting at least 8 hours of sleep during the school week (28%) than white (33%) and Hispanic (33%) students.8 Representative surveys of 15-19-year-olds in Brazil found that insufficient sleep duration increased from 2001 through 2011 and was associated with higher family income only in the more recent cohort.15

There is a developing body of research on the role of the neighborhood context, including the physical and social environments, on children’s sleep. Using census data to construct a measure of neighborhood social fragmentation, Pabayo and colleagues demonstrated that those adolescents living in neighborhoods with moderate to high social fragmentation were less likely to obtain at least 8.5 hours of sleep per night.16 A study among Mexican American adolescents found that those whose parents reported more neighborhood crime had fewer hours of nightly sleep and youth in higher crime neighborhoods napped more.17 Using nationally-representative US data from 2007, Singh and colleagues reported that parents living in more deprived neighborhoods were more likely to report their child having insufficient sleep than parents living in more advantaged neighborhoods.18

An overarching gap in the literature remains—monitoring sleep and identifying disparities across the life course at the population-level. Past studies of sleep patterns in children and adolescents have not typically investigated both race and multiple indicators of socioeconomic status (SES). This paper helps fill the void by assessing the combined associations among race, SES, and other physical and social factors in sleep patterns among children and adolescents over time. We used data from three waves of a nationally-representative survey of US children aged 6-17 years from 2003 through 2011/12 to examine trends in inadequate sleep and social determinants of inadequate sleep across children’s age groups.

Methods

Data source

Over the past decade there have been three cross-sectional waves (2003, 2007, 2011/12) of the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), a nationally-representative telephone survey of children and adolescents aged 0-17 years and their families.19 In the first “2003 survey”, 102,353 interviews were conducted from January 2003 to July 2004 (55% response rate).20 In the second “2007 survey”, 91,642 interviews were conducted from April 2007 to July 2008 (47% response rate).21 In the third “2011/12 survey”, 95,677 interviews were conducted from February 2011 to June 2012 (54% response rate for landline sample and 41% for cell phone sample).22 For each survey, a parent or guardian (referred to as “parent”) was interviewed about one randomly-selected child in the household on his/her physical and mental health, family, and social context.19 At each contact, at least 70% of the survey respondents were mothers.

Among the 289,672 children and adolescents from all three surveys, the measure of sleep was asked only to parents of 6-17-year-olds. We further excluded surveys with missing information on the sleep question (1,797). This resulted in a final sample of 196,990 children and adolescents: 68,418 from 2003, 63,442 from 2007, and 65,130 from 2011/12.

Outcome measure

At each survey, a parent answered the following question about their child’s sleep: During the past week, on how many nights did [child] get enough sleep for a child his/her age? Responses were 0-7 days. If the interviewer was prompted, he/she was told to say that ‘enough sleep’ is whatever the parent defines it as for this child. We defined inadequate sleep as no (7 days per week) versus yes (0-6 days per week).18 Our definition implies that the child had at least 1 day during the past week of inadequate sleep. This study assesses parental perceptions of inadequate sleep, which may not correspond to actual sleep quality or quantity. We have used the phrase ‘sleep inadequacy’ throughout to indicate parent-reported sleep inadequacy.

Covariates

Parents provided information on a range of socio-demographic characteristics on their child and family as well as information on their physical and social environments. They reported on the child’s age, gender, and whether anyone in the household was employed at least 50 out of the past 52 weeks. A derived family structure variable was included in each dataset, which combined the: (a) number of parents or parent figures and (b) relationships of parents or other adults in the household (two parent, single mother, other family types). Parents were asked whether the child was of Hispanic or Latino origin and, separately, to report all race categories that apply from seven options. We combined these two questions to create a four category race/ethnicity variable (white, Hispanic, Black, Other/Multiple race). Parents reported the highest level of education attained by anyone in the household (2003 survey) or separately on the child’s mother, father, or the respondent (2007 & 2011/12 surveys). We derived a three-category measure of the highest education in the household (< high school, high school, > high school) for each survey. Parents were asked whether their child had any kind of health care coverage and, separately, whether the coverage was Medicaid or the state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). We combined these two questions to create a three-category insurance status variable (none, Medicaid/CHIP, private). A derived measure of household poverty level with imputed missing values was included in each dataset, which was created from both the number of people residing in a household and the total household income during the past year prior to taxes.20-22 A household’s percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) was based on the US Department of Health and Human Services Federal Poverty Guidelines. Parents reported how safe they felt their child was in their community or neighborhood, which was coded as safe (usually/always) versus unsafe (never/sometimes). Parents also reported on the degree to which they felt that “we watch out for each other’s children in this neighborhood” was coded as yes (definitely/somewhat agree) versus no (somewhat/definitely disagree).

Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses in Stata SE version 13.1 (College Station, TX, US) and the ‘svy’ and ‘subpop’ commands were used to account for the complex sampling design and compute standard errors.20-22 All percentages and regression models included survey sampling weights for the results to represent the population of non-institutionalized children aged 6-17 years.

Since sleep duration decreases from childhood through adolescence,9 all analyses were conducted separately for each age group (6-9 years, 10-13 years, 14-17 years). We first examined survey year trends and socio-demographic characteristics associated with inadequate sleep (defined as 0-6 days per week of not getting enough sleep) using Pearson’s chi-squared tests. All variables were subsequently included in unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models. Significance levels of P ≤ 0.05 were used for all analyses.

Results

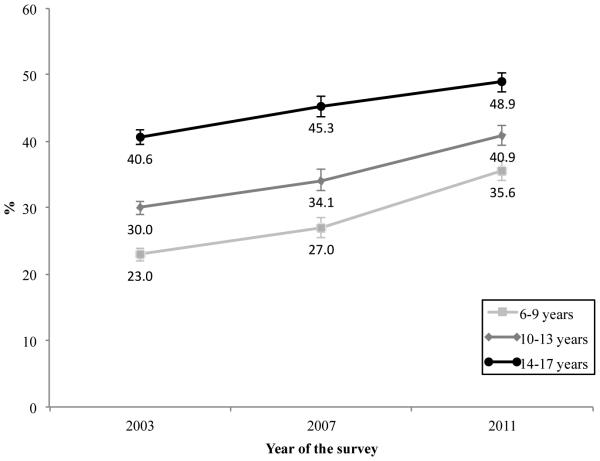

Figure 1 illustrates that there was a gradient in inadequate sleep across children’s age groups for all three survey periods, meaning that 6-9-year-olds had the lowest levels of inadequate sleep, followed by 10-13-year-olds, and 14-17-year-olds had the highest levels of inadequate sleep. However, the gap between age groups narrowed from 2003 through 2011/12. Parents reporting inadequate sleep increased from 23 to 36% among 6-9-year-olds, 30 to 41% among 10-13-year-olds, and 41 to 49% among 14-17-year-olds.

Figure 1.

Trends in inadequate sleep (defined as 0-6 days per week of not getting enough sleep) by children’s age groups across three surveys of the National Survey of Children’s Health (n = 196,990)

Note: For each age group, there was a significant increase in inadequate sleep across the three surveys (P ≤ 0.05).

The social determinants for inadequate sleep were relatively consistent across age groups in unadjusted analyses (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1). For all ages, inadequate sleep varied by children’s race/ethnicity, household education level, poverty level, and insurance status. Inadequate sleep also varied by parent report that neighbors did not watch out for other’s children among 6-13-year-olds only, household employment and perceived safety among children age 10-17 years, and by family structure only among older adolescents.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics of inadequate sleep (defined as 0-6 days per week of not getting enough sleep) by children’s age groups for all years of the National Survey of Children’s Health (2003, 2007, 2011) (n = 196,990)

| 6-9 years (n = 58,541) |

10-13 years (n = 64,139) |

14-17 years (n = 74,310) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variables | n (%a) | %a

Inadequate sleep |

n (%a) | %a

Inadequate sleep |

n (%a) | %a

Inadequate sleep |

|

| ||||||

| Year | ||||||

| 2003 | 20,182 (32.8) | 23.0b | 22,678 (34.1) | 30.0b | 25,558 (32.5) | 40.6b |

| 2007 | 18,099 (33.2) | 27.0 | 20,100 (32.7) | 34.1 | 25,243 (34.0) | 45.3 |

| 2011 | 20,260 (34.0) | 35.6 | 21,361 (33.3) | 40.9 | 23,509 (33.5) | 48.9 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 30,002 (51.6) | 28.0 | 32,935 (50.7) | 34.6 | 38,903 (51.1) | 44.8 |

| Female | 28,465 (48.4) | 29.3 | 31,116 (49.3) | 35.4 | 35,328 (48.9) | 45.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 38,110 (55.6) | 29.8b | 43,307 (57.7) | 37.5b | 53,185 (60.3) | 49.1b |

| Hispanic | 7,942 (20.7) | 26.0 | 7,797 (19.4) | 30.9 | 7,290 (17.3) | 35.7 |

| Black | 5,749 (14.3) | 29.4 | 6,385 (14.5) | 33.3 | 6,977 (15.1) | 39.3 |

| Other/Multiple race | 5,659 (9.4) | 26.4 | 5,524 (8.4) | 32.1 | 5,708 (7.4) | 45.9 |

| Highest education in household | ||||||

| < High school | 3,316 (9.5) | 29.3b | 3,557 (9.6) | 32.5b | 3,724 (9.1) | 32.7b |

| High school | 9,719 (22.7) | 26.0 | 11,745 (23.9) | 30.1 | 13,415 (24.0) | 39.7 |

| > High school | 44,776 (67.8) | 29.4 | 48,094 (66.5) | 37.1 | 56,475 (66.9) | 48.7 |

| Household poverty level | ||||||

| 0-99% FPL | 7,718 (19.7) | 27.4b | 8,036 (18.7) | 29.8b | 7,720 (16.1) | 36.0b |

| 100-199% FPL | 11,127 (21.6) | 26.8 | 11,779 (21.4) | 33.4 | 12,383 (21.2) | 40.3 |

| 200-299% FPL | 10,557 (17.1) | 29.8 | 11,768 (17.5) | 34.9 | 13,187 (17.8) | 43.8 |

| 300-399% FPL | 9,380 (13.9) | 28.0 | 10,172 (14.3) | 37.6 | 11,938 (14.0) | 48.6 |

| 400%+ FPL | 19,759 (27.6) | 30.5 | 22,384 (28.0) | 38.2 | 29,082 (31.0) | 51.9 |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| None | 3,809 (7.9) | 24.7b | 4,423 (8.1) | 30.0b | 5,296 (9.1) | 37.3b |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 14,341 (31.2) | 26.9 | 14,290 (29.0) | 31.3 | 13,407 (24.8) | 38.1 |

| Private | 39,750 (60.9) | 29.9 | 44,736 (62.9) | 37.2 | 54,898 (66.0) | 48.7 |

| Anyone in household employed at least 50 weeks |

||||||

| No | 5,371 (12.2) | 28.8 | 6,269 (12.3) | 32.7b | 7,130 (12.3) | 41.1b |

| Yes | 52,278 (87.8) | 28.7 | 56,921 (87.7) | 35.4 | 66,243 (87.7) | 45.7 |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Two parent | 44,000 (73.6) | 28.4 | 46,880 (72.3) | 34.8 | 54,248 (70.2) | 46.1b |

| Single mother | 10,064 (20.2) | 29.6 | 11,816 (21.4) | 36.7 | 13,684 (22.4) | 43.6 |

| Other family types | 3,608 (6.3) | 27.8 | 4,421 (6.3) | 33.3 | 5,264 (7.5) | 39.1 |

| Perceived safety | ||||||

| Safe | 51,014 (85.0) | 28.7 | 56,510 (86.0) | 34.6b | 66,905 (86.9) | 45.8b |

| Unsafe | 6,658 (15.0) | 27.9 | 6,729 (14.0) | 38.0 | 6,569 (13.1) | 40.6 |

| Neighbors watch out for other’s children |

||||||

| Yes | 52,023 (89.6) | 28.4b | 57,248 (89.7) | 34.9b | 65,681 (88.5) | 45.3 |

| No | 5,065 (10.4) | 31.6 | 5,339 (10.3) | 37.9 | 6,910 (11.5) | 45.6 |

FPL, Federal Poverty Level.

Missing values: gender (241), race (3,357), highest education (2,169), insurance status (2,040), employment (2,778), family structure (3,005), perceived safety (2,605), watch out for other’s children (4,724).

Weighted percentage.

P ≤ 0.05.

However, adjusted logistic regression models revealed that these relationships were quite dynamic across age groups from childhood through adolescence (Table 2). Although the largest increase in inadequate sleep over time was for children age 6-9 years old, overall differences across household education and income became more pronounced across the two older age groups. Among 10-17-year-olds, those who lived in households with more than a high school degree were 1.19-1.22 times more likely to have inadequate sleep than those who lived in households with only a high school degree. Among households with less than a high school degree, 10-13-year-olds were also 1.24 times more likely to have inadequate sleep. Although for children age 10-13 years there was a gradient in inadequate sleep across all four income levels (adjusted ORs [aOR] 1.20-1.34), for adolescents’ age 14-17 years, only those from the two highest income levels were more likely to have inadequate sleep (aORs 1.28-1.37).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of inadequate sleep (defined as 0-6 days per week of not getting enough sleep) according to socio-demographic characteristics by children’s age groups for all years of the National Survey of Children’s Health (2003, 2007, 2011) (n = 186,249)

| 6-9 years (n = 55,282) |

10-13 years (n = 60,573) |

14-17 years (n = 70,394) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variables | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

|

| |||

| Year | |||

| 2003 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2007 | 1.25 (1.13-1.38) | 1.28 (1.17-1.40) | 1.28 (1.18-1.39) |

| 2011 | 1.89 (1.73-2.07) | 1.76 (1.62-1.91) | 1.50 (1.39-1.63) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.04 (0.96-1.13) | 1.05 (0.97-1.12) | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 0.81 (0.71-0.94) | 0.75 (0.66-0.86) | 0.69 (0.60-0.79) |

| Black | 0.98 (0.86-1.11) | 0.82 (0.73-0.91) | 0.76 (0.68-0.85) |

| Other/Multiple race | 0.78 (0.66-0.91) | 0.74 (0.64-0.86) | 0.89 (0.77-1.03) |

| Highest education in household | |||

| < High school | 1.19 (0.96-1.47) | 1.24 (1.03-1.48) | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) |

| High school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| > High school | 1.07 (0.95-1.19) | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | 1.19 (1.09-1.31) |

| Household poverty level | |||

| 0-99% FPL | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 100-199% FPL | 1.00 (0.85-1.16) | 1.20 (1.05-1.39) | 1.09 (0.95-1.25) |

| 200-299% FPL | 1.12 (0.93-1.35) | 1.21 (1.03-1.41) | 1.09 (0.94-1.27) |

| 300-399% FPL | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) | 1.35 (1.13-1.60) | 1.28 (1.09-1.50) |

| 400%+ FPL | 1.12 (0.94-1.33) | 1.34 (1.15-1.58) | 1.37 (1.18-1.59) |

| Insurance status | |||

| None | 1.01 (0.82-1.25) | 1.02 (0.87-1.21) | 1.03 (0.87-1.20) |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Private | 1.17 (1.03-1.32) | 1.18 (1.05-1.33) | 1.21 (1.08-1.35) |

| Anyone in household employed at least 50 weeks |

|||

| No | 1.00 (0.86-1.15) | 0.95 (0.83-1.08) | 1.11 (0.98-1.26) |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family structure | |||

| Two parent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Single mother | 1.18 (1.05-1.32) | 1.34 (1.21-1.48) | 1.15 (1.05-1.27) |

| Other family types | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) | 1.09 (0.93-1.28) | 0.83 (0.71-0.96) |

| Perceived safety | |||

| Safe | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unsafe | 1.02 (0.89-1.16) | 1.35 (1.19-1.54) | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) |

| Neighbors watch out for other’s children |

|||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 1.26 (1.09-1.47) | 1.20 (1.06-1.37) | 1.13 (1.00-1.28) |

CI, confidence interval; FPL, Federal Poverty Level; OR, odds ratio Significant findings are in bold.

Models are mutually adjusted for all covariates

Associations between inadequate sleep and children’s race/ethnicity, insurance status, and family structure were similar across age groups (Table 2). Overall, Hispanic (aORs 0.69-0.81) and Black children (aORs 0.76-0.82) and children of Other/Multiple race (aORs 0.74-0.78) were less likely have inadequate sleep than white children. Children and adolescents with private insurance (aOR 1.17-1.21) or from single mother households (aOR 1.15-1.34) were more likely to have inadequate sleep than those with Medicaid/CHIP or from two-parent families, respectively. There were no differences in inadequate sleep by gender or household employment status across age groups.

Examining the role of the neighborhood context, parent report that neighbors did not watch out for other’s children was associated with an increased risk for inadequate sleep across all ages (aORs 1.13-1.26). In contrast, parents’ perceiving they lived in an unsafe community/neighborhood was associated with a 1.35 higher odds of inadequate sleep only among children age 10-13 years.

Discussion

Using nationally-representative data of US children and adolescents, we found that inadequate sleep occurred as young as age 6 years and increased with age, became more prevalent over time, and was socially patterned. In 2011/12, between one-third and one-half of parents reported their child age 6-17 years did not get enough sleep on 0-6 days out of the past week. Differences in inadequate sleep across household education and income also became more pronounced with age, such that parents of 14-17-year-olds from the most advantaged households had the highest likelihood of reporting inadequate sleep. Parent report that neighbors did not watch out for other’s children--a measure of the social environment--was also associated with an increased risk for inadequate sleep across all groups. Considering the strong gradients in sleep, our findings suggest that national monitoring and surveillance of sleep needs to extend to all age groups.

A developing evidence base1 has shown that children and adolescents with sleep issues are more likely to have poor performance in school,2 daytime sleepiness and inattention,3 and be obese.4 However, research suggests that sleep quantity and quality may both matter.2, 3 For example, poor sleep quality23 and shorter sleep duration24, 25 have been independently associated with motor vehicle accidents and unintentional injuries in adolescents. The Healthy People 2020 target to increase the proportion of high school students who get sufficient sleep is measured by the proportion of adolescents who self-report getting at least 8 hours of sleep on an average school night in the YRBS.7 While this question measures sleep duration, it does not capture sleep quality. In contrast, the NSCH asks parents to report on sleep quality, but not sleep duration. We believe that the clinical and public health benefits of more fully understanding both sleep quantity and quality would outweigh the potential economic cost and time burden to participants of including at a minimum one additional question to these surveys. However, if time and resources allow, using a validated survey, such as the Sleep Habits Survey,26 or assessing multiple dimensions, such as difficulties initiating sleep, sleep disturbances, and daytime sleepiness,10 would provide a more comprehensive assessment of sleep.

Our findings add to the limited number of studies on the social determinants of sleep in children and adolescents. Although there were no differences in inadequate sleep by household education and income for children age 6-9 years, they emerged and strengthened across the teenage years. Adolescents from households with higher levels of education and income were more likely have inadequate sleep than children from more disadvantaged households. While prior research has found that children from more disadvantaged circumstances had lower sleep quality and shorter sleep duration,5, 13, 14 a recent study in Mexican American adolescents showed that higher levels of parental income and education were associated with fewer hours of nightly sleep.17 Hoefelmann and colleagues also found that Brazilian adolescents from high income families had poorer sleep quality and shorter duration in 2011, but not in the survey administered a decade prior.15 Although it is not possible to test potential mechanisms in the NSCH, such as higher SES parents over-reporting inadequate sleep or their children using more technology at bedtime, this is an area for future research. Consistent with other studies, we have shown that sleep issues increase with age9, 10 and are becoming more prevalent,15 suggesting that differences in findings may be explained by time and cohort effects. Due to increased awareness of the importance of sleep, there is also the potential for reporting bias and an under-reporting of inadequate sleep.

Only a few studies have examined racial/ethnic differences5 and recent studies have shown that Black students were less likely to obtain the recommended amount of sleep than their white and Hispanic peers.8, 27 We found that parents of Hispanic children across all age groups were less likely to report inadequate sleep than white children and parents of Black children were also less likely to report inadequate sleep in the two older age groups. As racial differences in sleep issues reflect the social conditions of life, it is imperative to consider socioeconomic circumstances in conjunction with race. It is possible, for example, that the advantages that accrue around race, income and education, may provide more opportunities and resources like computers, video games, and social gatherings that actually lead to inadequate sleep especially during childhood and adolescence.

More recent evidence indicates that both the physical and social environments may impact children’s sleep. Consistent with other studies examining the role of crime and neighborhood disadvantage17, 18 we found that parents’ perceived safety of their neighborhood/community was associated with inadequate sleep, but only for children age 10-13 years. The resources individuals’ access through their involvement in a neighborhood or community is referred to as social capital.28 We found that children whose parents reported that neighbors did not watch out for other’s children were at an increased risk for inadequate sleep and these results were consistent across all age groups. This question measures the social environment, and potentially the level of neighborhood cohesion, which is different to a measure of the physical environment. While Pabayo and colleagues found that adolescents who lived in neighborhoods with moderate to high social fragmentation, indicating greater residential instability, were less likely to obtain at least 8.5 hours of sleep per night,16 our results suggest that children’s sleep may be impacted by lower social capital even at younger ages. Additional research is needed to understand different measures of social capital and how they impact sleep across the life course.

The Institute of Medicine’s 2006 report, Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem recommended additional surveillance and monitoring of sleep patterns and sleep disorders (recommendation 5.3).1 We reviewed the major national health surveys in the US to identify those that included a question on sleep for children and adolescents as well as the years of data collection, ages, and reporting method. Table 3 highlights that only three national questionnaires ask about sleep, it is not monitored in children younger than age 6, and there is little consistency in the sleep questions, responses, and reporting methods. Furthermore, sleep health in children and adolescents was not monitored nationally prior to 2003. As we have shown, from 2003 through 2011/2012, the proportion of 6-9-year-olds with inadequate sleep increased from 23 to 36%. Although this suggests that insufficient sleep is likely developing between infancy and childhood, there are currently no nationally-representative surveys in the US capturing these changes in sleep patterns. Collecting information on multiple dimensions of sleep,10 consistently across surveys, and across the life course is essential to help prevent sleep issues and the associated physical and mental health consequences.

Table 3.

Overview of US national health surveys with questions on sleep for children and adolescents

| Name of survey | Years of data |

Ages | Reporting method |

Sleep questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Survey of Children’s Health |

2003, 2007, 2011/12 |

6-17 years |

Parental report |

During the past week, on how many nights did [child] get enough sleep for a child his/her age? (Parental response: 0-7 days) |

| Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015 |

14-18 years |

Self-report | On an average school night, how many hours of sleep do you get? (Self-report response: 4 or less hours, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 or more hours) |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

2005- 2006, 2007- 2008, 2009- 2010, 2011- 2012, 2013- 2014 |

16+ years |

Self-report | From sleep disorders questionnaire: How much sleep do you usually get at night on weekdays or workdays? (Self-report response: hours and minutes) In the past month, how often did you not get enough sleep? (Self-report response: never, rarely, sometimes, often, almost always) |

Despite the NSCH being nationally representative, there are limitations to the dataset. In the NSCH, children’s sleep was assessed by only one question and answered by parents. Although objective measures of sleep, such as actigraphy,29 more accurately capture multiple dimensions of sleep than subjective measures, most national surveys use parental-or self-report of sleep due to cost and time constraints. A few studies have evaluated the accuracy of data collection between objective and subjective measures. Dayyat and colleagues showed that parents of 3-10-year-olds reported significantly longer sleep duration compared to actigraphic estimates.30 Similarly, Short and colleagues found that parents of adolescents age 13-17 years estimated significantly earlier bedtimes and more sleep than either adolescent self-report or actigraphic estimates.31 Together, these studies suggest that the NSCH may actually under-estimate the true prevalence of inadequate sleep. An additional limitation is that the NSCH assesses parental perceptions of inadequate sleep and not actual sleep quality or quantity. It is possible that parents from different income groups or racial/ethnic backgrounds may have different perceptions about how much sleep their children need to adequately function. Since parental-and/or self-report measures will likely continue in national studies, further research is needed on how to reduce discrepancies between objective and subjective measures and maximize the generalizability of the findings.

Although the aim of our study was to examine trends in and the social determinants of inadequate sleep, more research is needed to examine the mechanisms, particularly during the transition from childhood through adolescence. For example, the rise in media use over the past decade has been identified as a potential risk factor.32 However, an ecological systems approach examining individual (i.e. sports participation, media in the bedroom), family (i.e. SES, media rules), and neighborhood factors (i.e. crime, social cohesion) may help identify potential explanations and areas for intervention.

As of 2011/12, parents reported that up to one half of children and adolescents had inadequate sleep on at least one night during the past week. This places a substantial portion of the US population at higher risk for the physical and mental health consequences of poor sleep.1-5 In order to prevent inadequate sleep across the life course, surveillance and monitoring is needed across all age groups to identify critical periods for intervention. Enquiring about sleep could be integrated into routine clinical care during well-child visits from birth through adolescence. National surveys also need to enquire about sleep using consistent questions and reporting methods to allow for comparability. Although recognizing ‘Sleep Health’7 as a national priority is an important advancement in public health for adolescents and adults, recognizing that sleep is critical at all ages is essential to improving population-level health across the life course.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

From 2003 through 2011/12, inadequate sleep increased across childhood

Inadequate sleep occurred as young as age 6 years

Inadequate sleep was socially patterned by household education and income

In order to prevent inadequate sleep across the life course, surveillance and monitoring is needed across all age groups to identify critical periods for intervention

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00HD068506 to Dr. Hawkins. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funder had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CHIP

Children’s Health Insurance Program

- FPL

federal poverty level

- NSCH

National Survey of Children’s Health

- OR

odds ratio

- SES

socioeconomic status

- YRBS

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethical approval

The Boston College Institutional Review Board reviewed the study and considered it exempt.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Colton HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkof GA, Bogels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beebe DW. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):649–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen LS, Danielsen KV, Sorensen TI. Short sleep duration as a possible cause of obesity: critical analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Obes Rev. 2011;12(2):78–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knutson KL. Sociodemographic and cultural determinants of sleep deficiency: implications for cardiometabolic disease risk. Soc Sci Med. 2013;79:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute How much sleep is enough? Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sdd/howmuch.html. Accessed on May 27, 2014.

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services Sleep health. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. Available from: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/TopicsObjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=38. Accessed on May 20, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl 1):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MW. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 2011;12(2):110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sleep and sleep disorders: data and statistics. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.htm. Accessed on May 6, 2014.

- 12.Dixon B, Pena MM, Taveras EM. Lifecourse approach to racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):73–82. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Drotar D, Rosen CL, Kirchner LH, Benham H, et al. Sleep behavior in an urban US sample of school-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(10):988–94. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrin DC, McGrath JJ, Quon EC. Objective and subjective socioeconomic gradients exist for sleep in children and adolescents. Health Psychol. 2014;33(3):301–5. doi: 10.1037/a0032924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoefelmann LP, Lopes Ada S, da Silva KS, Moritz P, Nahas MV. Sociodemographic factors associated with sleep quality and sleep duration in adolescents from Santa Catarina, Brazil: what changed between 2001 and 2011? Sleep Med. 2013;14(10):1017–23. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pabayo R, Molnar BE, Street N, Kawachi I. The relationship between social fragmentation and sleep among adolescents living in Boston, Massachusetts. J Public Health. 2014;36(4):587–98. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHale SM, Kim JY, Kan M, Updegraff KA. Sleep in Mexican-American adolescents: social ecological and well-being correlates. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40(6):666–79. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9574-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh GK, Kenney MK. Rising prevalence and neighborhood, social, and behavioral determinants of sleep problems in US children and adolescents, 2003-2012. Sleep Disord. 2013;2013:394320. doi: 10.1155/2013/394320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) 2003, 2007 & 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health Indicator Data Sets. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. www.childhealthdata.org.

- 20.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel MR, Osborn L, Srinath KP, Giambo P. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2003. Vital Health Stat 1. 2005;(43):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumberg SJ, Foster EB, Frasier AM, Satorius J, Skalland BJ, Nysse-Carris KL, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1. 2012;(55):1–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health Frequently Asked Questions. 2013 Apr; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.

- 23.Pizza F, Contardi S, Antognini AB, Zagoraiou M, Borrotti M, Mostacci B, et al. Sleep quality and motor vehicle crashes in adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(1):41–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam LT, Yang L. Short duration of sleep and unintentional injuries among adolescents in China. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(9):1053–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martiniuk AL, Senserrick T, Lo S, Williamson A, Du W, Grunstein RR, et al. Sleep-deprived young drivers and the risk for crash: the DRIVE prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):647–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Seifer R, Fallone G, Labyak SE, et al. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep. 2003;26(2):213–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong WW, Ortiz CL, Lathan D, Moore LA, Konzelmann KL, Adolph AL, et al. Sleep duration of underserved minority children in a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:648. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social Epidemiology. Second Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meltzer LJ, Montgomery-Downs HE, Insana SP, Walsh CM. Use of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep research. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(5):463–75. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dayyat EA, Spruyt K, Molfese DL, Gozal D. Sleep estimates in children: parental versus actigraphic assessments. Nat Sci Sleep. 2011;3:115–23. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S25676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright H, Carskadon MA. The discrepancy between actigraphic and sleep diary measures of sleep in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2012;13(4):378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cain N, Gradisar M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. Sleep Med. 2010;11(8):735–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.