Abstract

BACKGROUND

Few efficacious topical therapies exist for chronic rhinosinusitis. The lack of a reproducible mouse model of CRS limits the pilot testing of potential novel anti-inflammatory therapies. Although the ovalbumin induced mouse model of sinonasal inflammation is commonly used, it is difficult to reproduce and can generate variable histologic results. In this study, we explore a variation of this model in different strains of mice and explore various inflammatory cytokines as reproducible molecular markers of inflammation.

METHODS

Allergic sinonasal inflammation was generated in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice using intraperitoneal high dose injections of Ova followed by 10 days of high dose intranasal sensitization. Real-Time PCR for eotaxin, IL4, and IL13 were measured from sinonasal mucosa. We also pilot tested a known topical budesonide to characterize the anti-inflammatory response. Histological sections were analyzed for epithelial thickness and eosinophilia.

RESULTS

Both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice consistently showed increases in Th2 cytokines after sensitization with high dose Ova (p<0.0001) when compared to controls. There were also significant increases in epithelial thickening in Ova sensitized mice and eosinophilia in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 strains.In addition, topical budesonide significantly reduced anti-inflammatory cytokines, eosinophilia, and epithelial thickness.

CONCLUSION

Our variation of the ovalbumin induced mouse model of sinonasal inflammation in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice provides an efficacious model for testing potential topical anti-inflammatory therapies for CRS. The utilization of sinonasal mucosal Th2 cytokines along with histologic markers provides a consistent and quantifiable marker of inflammation in assessing the efficacy of candidate drugs.

Background

Sinus disease represents one of the most common healthcare problems in the United States, affecting approximately 16% of the population1,2, with a cost exceeding $8 billion per year, and causing a significant adverse effect on the quality of life3. The underlying pathologic cause of persistent inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) remains poorly understood4. As a result, the few available medical therapies generally concentrate on decreasing mucosal inflammation and eliminating sources of infection.

In order to study the cellular and molecular basis of rhinosinusitis, model systems have been developed in animal species5. The murine model has been commonly used due to the availability and ease of manipulation of gene expression experimentally6. Using a mouse model, however, presents multiple challenges. While multiple models have been used to produce inflammation, a mouse model specific for CRS does not yet exist. The ovalbumin-induced mouse model of sinonasal inflammation is the most commonly used model, but the induced inflammatory response can be difficult to reproduce7.

The histologic results in mouse models of mucosal inflammation often generate variable results. Determination of tissue eosinophil counts in histologic sections is a common approach to reporting tissue inflammation. Calculation of tissue eosinophils for statistical comparisons, however, carries a high inherent variability8. Real time PCR, on the other hand, is a more quantitative method that may provide a consistent measure of tissue inflammation9. Therefore, this study will explore a variation of a high dose ovalbumin-induced sinonasal inflammation model, while utilizing real-time PCR for levels of known inflammatory markers from sinonasal mucosal cDNA, to quantify the sinonasal inflammatory response in mice. This study will also compare the use of sinonasal lavage cytokine measurements and histologic analysis, including eosinophil counts.

Methods

Animals

BALB/c (Total n=11, controls=4, Ova treated=7) and C57BL6/J (Total n=19, Controls=4, Ova treated= 15) mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility with single ventilated cages and received OVA-free diet. All animal experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ovalbumin Sensitization

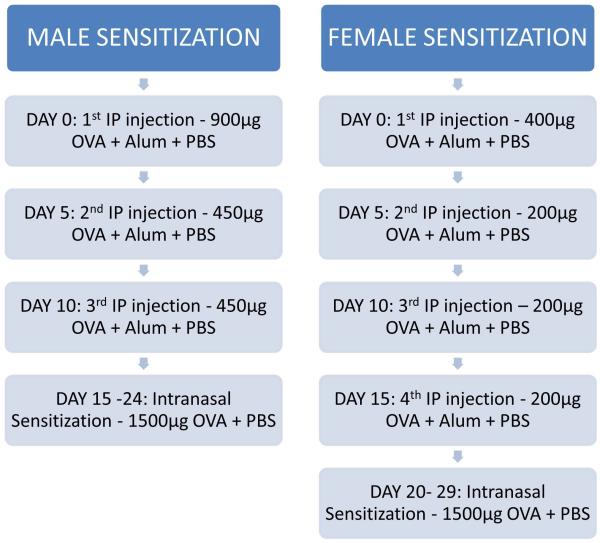

Ovalbumin (Ova, grade V; Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO) was used in BALB/c and C57 BL6/J mice. Mice received different sensitization protocols based on sex primarily due to whole body weight (Figure 1). Male mice were sensitized on day 0 by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of approximately 900μg of Ova in 76.9μL of Alum adjuvant and 103.1μL of PBS. On days 5 and 15 these mice received additional IP injections of approximately 450μg of Ova in 76.9μL of Alum adjuvant and 103.1μL of PBS. Female mice were sensitized on day 0 by IP injection of approximately 400μg of Ova in 76.9μL of Alum adjuvant and 103.1μL of PBS. On days 5, 15, and 20 these mice received additional IP injections of approximately 200μg of Ova in 76.9μL of Alum adjuvant and 103.1μL of PBS. Males on day 20, and females on day 25, began nasal sensitization via intranasal challenges of approximately 1500μg of Ova in 20μL of PBS distributed equally between the two nostrils. Control groups of mice were sensitized similarly with IP injections, but were challenged intranasally with equivalent volumes of PBS.

Figure 1.

A diagram of our modified ovalbumin sensitization protocol for male and female mice

Anti-Inflammatory Intervention with Sinonasal Topical Budesonide

The ovalbumin sensitization protocol can be modified to measure drug efficacy. In this study, both Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal Ova in a standard fashion. Intranasal challenges with ova were extended for 10 extra days with the Ova dissolved in an equivalent volume of budesonide (10 μM) instead of saline.

Harvesting of Sinonasal Mucosa

Sinonasal mucosa was extracted from mouse heads as previously described6. In brief, mice were heavily sedated with an intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine per our standard protocol. Incisions along the abdomen to the rib cage were made to expose the inner organs and heart. A catheter was then inserted into the left ventricle of the heart to perfuse the circulatory system with phosphate buffered saline. Perfusions were continued until the intercostal veins were cleared of blood and the liver became pale in color. Mice were then decapitated and the lower jaw and tongue were removed. The pharynx was located and a flexible catheter was inserted into the opening and 800 microliters of phosphate buffered saline was flushed through both nares as previously described. 6 Next, the skull was split in half slightly off-center in order to preserve one side of the nasal cavity in its entirety. To harvest nasal tissues for mRNA extraction, the skull was bisected in a sagittal orientation, and septal and turbinate mucosa were removed and placed in 1 ml of RNAlater solution (Ambion, Inc). The other half of the head was used for histology.

Histologic Analysis

For nasal histology, mouse heads were fixed with paraformaldehyde and decalcified for 2 days before embedment in paraffin. Coronal paraffin sections were cut on a microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or alcian blue/periodic acid schiff. Images were acquired using the Zeiss Axio Imager.A2 microscope and measurements made using the Axiovision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss Micro-imaging, Thornwood, NJ). To demonstrate mucosal remodeling, epithelial thickness was measured at the same respiratory turbinate locations, from the basement membrane to the nasal lumen.

Confocal Microscopy

Immunohistological staining was performed on 12μm sections. Briefly, sections were blocked in 10% Normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X 100 in PBS. After incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, the slides were washed in PBS and then incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488/568 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Sections were then washed, counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen). Primary antibodies used in this study include rabbit anti-Krt5 (Covance, 1:500, PRB-160P) and Goat anti-Eosinophilic major basic protein (EMBP) (Santa Cruz, 1:200, sc-33938). Confocal images were collected with a LSM700 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). EMBP+ cells in sections of respiratory epithelium were counted. Data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically and absorbance ratios at 260/280 nm were >1.80 for all samples studied. Five hundred nanograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a 20 μl volume with random hexamer primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen) under conditions provided by the manufacturer.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Real-time PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus machine (Foster City, CA) under standard cycling parameters. The Taqman gene expression system (Applied Biosystems) was used to measure Th2 cytokine mRNA levels of IL-4, IL-13, and CCL-11 (mouse eotaxin-1). The reaction mix consisted of 0.5 μg total RNA for target genes or 0.05 ng total RNA for 18S, 10 μl of TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix, 1.5–5 mol/L probe target genes or 1.0 mol/L probe 18S, in a total volume of 20 μl. Each PCR run was accompanied by housekeeping gene 18S as an internal control. Amplicon expression in each sample was normalized to its 18S RNA content and the level of expression of target mRNA was determined as the delta Ct, the difference in threshold cycles for each target and housekeeping gene. Relative gene expression was calculated by the 2−ΔCt.

Enzyme-Linked Immuno Assay (ELISA) for Eotaxin-1

Nasal lavages were spun down cells at 14000rpm for 10 minutes. Supernatants were then used to assess concentrations of eotaxin-1 (CCL11) by ELISA (R & D Systems).

Statistical analysis

All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation of the mean. Total cell and differential cells count in three groups were compared with two-way ANOVA test. The expression of inflammatory mediator mRNA between genetically matched groups was compared with non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney test). Statistical significance was considered to be P<0.05. Results were analyzed with the use of the statistical software Prism 4 (GraphPad, Inc).

Results

Ovalbumin Sensitization is Associated with Increases in Eotaxin-1, IL-4, and IL-13 mRNA Expression

Overall, both C57BL/6 (BL6) and BALB/c strains of mice that underwent ovalbumin sensitization resulted in significant increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression from mouse sinonasal mucosa. On average, sensitization created a 4-5 cycle increase (16-32 fold increase) in expression of eotaxin-1 when compared to saline challenged mice (p<0.0001), (Figure 2). Saline challenged mice did not express any IL-4 or IL-13, however ovalbumin challenge resulted in statistically significant increases (p<0.0001), (Figure 3). In addition, ovalbumin challenges also induced increased in mRNA expression of the mucin gene MUC5AC, with a 12 fold increase in BALB/c mice and a 3 fold increase in C57BL/6 mice (data not shown).

Figure 2.

mRNA Expression of Eotaxin-1 in C57BL/6 (n=11, control=4, Ova=7, all male) and BALB/c (n=19, control=4, Ova=15, all male) mice measured by RT-PCR of sinonasal mucosal membranes. All values are normalized to 18S.

Figure 3.

mRNA Expression of IL-4and IL-13 in C57BL/6 (n=11, control=4, Ova=7, all male) and BALB/c (n=19, control=4, Ova=15, all male) mice measured by RT-PCR of sinonasal mucosal membranes. All values are normalized to 18S

Both C57BL/6 and BALB/c Mice Create Similar Levels of Allergic Inflammation assessed by RT-PCR

When the sinonasal mucosal mRNA expression was compared between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice challenged with ovalbumin, there appear to be no statistically significant differences in expression of the Th2 associated inflammatory cytokines eotaxin, IL-4, IL-13, or MUC5AC mucin gene expression.

Sinonasal Lavages show increased levels of Eotaxin measured through ELISA

Since eotaxin-1 was the most robustly expressed cytokine by RT-PCR, ELISA was performed on lavages to measure protein concentrations of eotaxin-1. Sinonasal lavages collected at the time of sacrifice demonstrated significant increases in eotaxin-1 when challenged with ovalbumin. Both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice demonstrated statistically significant increases in eotaxin when compared to saline challenged mice (Figure 4). In comparing eotaxin levels between ovalbumin challenged mice amongst the different strains, BALB/c mice had a statistically significant increase when compared to C57BL/6 mice (p=0.02).

Figure 4.

Measurement of Eotaxin-1 levels in sinonasal lavages measured by ELISA (pg/mL). Both C57BL/6 (n=11, control=4, Ova=7, all male) and BALB/c (n=19, control=4, Ova=15, all male) mice individually showed statistically significant increases after ovalbumin sensitization.

Ovalbumin sensitization is associated with consistent increases in epithelial thickness and tissue eosinophilia

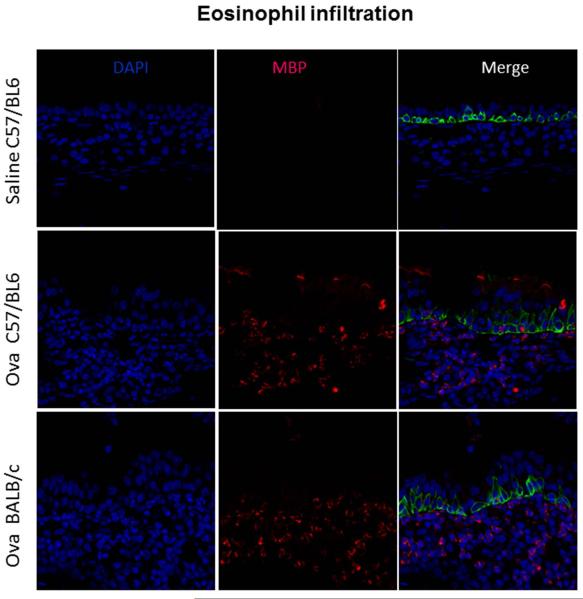

Sectioned mouse head were stained with hematoxylin and eosin at the level of the septum and mid-turbinate (Figure 5). Histology demonstrates increased epithelial thickness in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice after ovalbumin sensitization quantified by measurements taken 3-3.5 mm from the tip of the nose (Figure 6, P<0.001). In addition BL6 ova challenged mice demonstrate goblet cell hyperplasia and enhanced mucus production. Tissue eosinophilia, quantified by measuring EMBP via confocal microscopy, also shows robust eosinophil counts in both BALB/c and C57BL/6. BALB/c mice did have a statistically significant increase in tissue eosinophils when compared to C57BL/6 mice, p<0.001 (Figures 7-8)

Figure 5.

Hematoxylin & Eosin Staining. A. BALB/c Maxilloturbinate OVA intranasal challenge (10X), B. BALB/c Septum OVA intranasal challenge (10X), C. C57BL/6 Maxilloturbinate OVA intranasal challenge (10X), D. C57BL/6 Septum OVA intranasal challenge (10X), Note mucosal surfaces with inflammatory infiltrates and increased epithelial thickening. Sample Size: C57BL/6 (n=11, control=4, Ova=7, all male) and BALB/c (n=19, control=4, Ova=15, all male)

Figure 6.

Measurement of epithelial thickness at the level of the maxilloturbinate and nasal septum taken at 3-3.5 mm from the tip of the nose. Reported as μM measured at 10X. There is a statistically significant increase between saline and ovalbumin challenged C57BL/6 (n=11, control=4, Ova=7, all male) and BALB/c (n=19, control=4, Ova=15, all male) mice, p<0.001.

Figure 7.

Confocal microscopy at 40X, all male mice. Blue Cells= DAPI, all viable cells, Red Cells= MBP (major basic protein specific for eosinophils), Green Cells= Krt5, epithelial cells. The top row is a saline challenged C57BL/6 mouse, middle row is an Ova challenged C57BL/6 mouse, bottom row is an Ova challenges Balb/c mouse. Note the significant increase in red cells (positive for eosinophilic major basic protein) in the merged panels in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. The saline challenged BALB/c mice also demonstrate no eosinophils (not shown). Sections were cut from half of the total number of control and Ova challenged mice in each strain, C57BL/6 (n=6, control=2, Ova=4, all male) and BALB/c (n=9, control=2, Ova=7, all male).

Figure 8.

Comparison of tissue eosinophil counts at 40X, cells per μm of tissue in control (saline) versus Ova challenged C57BL/6 mice (A) and BALB/c mice (B). BALB/c mice have statistically significant increases in tissue eosinophilia compared to C57BL/6, p<0.001. Samples Size: C57BL/6 (n=6, control=2, Ova=4, all male) and BALB/c (n=9, control=2, Ova=7, all male).

Therapeutic intervention with budesonide results in decreased sinonasal inflammation

Treatment of both C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice for an additional 10 days with budesonide following Ova challenges was associated with statistically significant reduction in eotaxin, IL-4, and IL-13 mRNA expression (p<0.003) in C57BL/6 mice. There was also decreased epithelial thickness (p<0.005), in addition to a reduction in tissue eosinophilia when compared to Ova challenges alone (p<0.001) in BALB/c mice (Figures 9-11).

Figure 9.

mRNA Expression of eotaxin, IL-4, and IL-13 in Ova sensitized C57BL/6 (n=4, male) and BALB/c (n=4, male) mice combined before and after topical budesonide treatment measured by RT-PCR of sinonasal mucosal membranes. All values are normalized to 18S, p<0.003 for all cytokines.

Figure 11.

Epithelial layer thickness measurement at the level of the maxilloturbinate and nasal septum in Ova challenged C57BL/6 mice before and after budesonide treatment, 10 μM. Taken at 3-3.5 mm from the tip of the nose. Reported as μM measured at 10X. There is a statistically significant increase between budesonide treated and untreated mice, p<0.005. Sample Size: C57BL/6 (n=4, male) and BALB/c (n=4, male)

Discussion

The lack of a true mouse model of sinonasal inflammation has impeded the development of novel topical therapies for the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Currently there are no reliable genetic mouse models of rhinitis or sinusitis. The most popular non-genetic mouse models of allergic sinonasal inflammation are based on modifications of previously well characterized lower airway models using various concentrations and sensitization protocols with ovalbumin, aspergillus, or common allergens such as house dust mite 10-12.

The primary purpose of this study is to standardize a sensitization protocol and determine which molecular markers best consistently and reliably assess the sinonasal inflammatory response. In our unique sensitization protocol, all mice received significantly higher concentrations of ovalbumin during intraperitoneal injections compared to other studies which routinely use 100 ug. In our protocol, we routinely use 3 injections (900 ug, followed by 2 doses of 450 ug) for male mice and a reduced dose spread over 4 injections for females (400 ug, followed by 3 doses of 200ug) (Figure 1). Our protocol also anesthetizes mice during the intranasal challenges to ensure that allergen stays in the nose for longer.

Since this type of mouse model is non-genetic and requires meticulous experimental techniques, there can be varying levels of sinonasal inflammation. Unlike the lower airway models of inflammation that use intra-tracheal instillations of ovalbumin, the sinonasal model uses an intranasal route which can be technically challenging as mice can easily aspirate or swallow the ovalbumin. In addition, research groups utilize different sensitization protocols, varying both the dosage and timing of ovalbumin administration. Some protocols administer intraperitoneal doses of ovalbumin or allergen followed by intranasal challenges while others only give intranasal challenges.11,13,14 Lastly, the experimental techniques used to assess levels of sinonasal inflammation also vary greatly. While some groups rely heavily on qualitative measures such as histology and the presence of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and behavioral changes such as nasal rubbing and sneezing, others measure cytokine levels in sinonasal lavage fluid or sinonasal mucosal tissue.12,14-16 Clearly, there can be a high degree of variability in both the creation and characterization of the allergic sinonasal mouse model.

Our data demonstrates that ovalbumin sensitization using our protocol results in statistically significant increases in mucosal eotaxin, IL-4, and IL-13 mRNA expression with minimal variation between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (Figures 2-3). This result is significant as we are not aware of another group that has been able to successfully create allergic sinonasal inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. Numerous studies have suggested that ovalbumin induced allergic inflammation in the lung may be mouse strain dependent, favoring enhanced airway inflammation via activation of the transcription factor NF-kB in BALB/c mice. 17-19 As a result, most ovalbumin induced sinonasal allergic inflammation models utilize BALB/c mice. The ability to generate allergic sinonasal inflammation in C57BL/6 mice saves time as many genetically modified knock-out and transgenic mice targeting genes involved in chronic sinusitis are often only available on the C57BL/6 background. Alternatively, these genetically modified mice can also be back-crossed onto the BALB/c background.

Measurement of eotaxin in the sinonasal lavages by ELISA also demonstrates a statistically significant increase between saline and ovalbumin challenged C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (Figure 4). BALB/c mice did have a more robust response compared to C57BL/6 mice. Since sinonasal lavages are performed through the pharyngeal inlet and out the nose, these specimens can also take into account the cytokines that are generated in the pharynx, likely also from ovalbumin sensitization that dribbles down the nose.

The other measures of successful allergic sensitization such as histology and measurements of epithelial thickness also demonstrated increases after ovalbumin sensitization specifically in the area of the maxilloturbinate (Figure 5-6). Lastly, a hallmark of allergic inflammation is tissue eosinophilia. Traditionally, most groups use hematoxylin and eosin staining to identify eosinophils which can generate significant inter-observer variability. In this study, we utilized a monoclonal antibody for eosinophilic major basic protein (EMBP) followed by confocal imaging to quantify eosinophils. We demonstrate robust eosinophilia in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice with a significant increase in BALB/c mice, p<0.001 (Figure 8). We feel that these more qualitative measures are supportive adjunctive rather than primary assessments.

The primary application of using the allergic model of sinonasal inflammation is testing of novel topical or systemic drugs to reverse inflammation. 8,13,14,16,20,21 In order to determine the most sensitive and reliable measure of drug efficacy, we pilot tested a common topical anti-inflammatory drug used in treating CRS, budesonide, in the allergic mouse model. We demonstrate significant reduction in eotaxin, IL-4, and IL-13 mRNA expression after 10 days of budesonide treatment as well as histologic changes focused on a reduction in epithelial thickness and tissue eosinophilia.

In this study, we demonstrate that measuring Th2 cytokine mRNA expression in the sinonasal mucosa of sensitized mice is robust and reproducible when using our high dose ovalbumin protocol. Other parameters such as sinonasal lavage cytokine measurements and histologic analysis, although more variable, may still be valuable in confirming mucosal mRNA cytokine measurements.

In conclusion, our variation of the ovalbumin induced mouse model of sinonasal inflammation in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice provides an excellent model for testing potential topical anti-inflammatory therapies for CRS. To our knowledge, this is the first report of generating a successful allergic sinonasal inflammation model in C57BL/6 mice. The utilization of sinonasal mucosal eotaxin, IL4, and IL13 levels in conjunction with other parameters such as confocal microscopy using a monoclonal antibody specific for eosinophilic major basic protein provides a consistent and quantifiable marker of inflammation in assessing the efficacy of topical candidate drugs to reverse sinonasal inflammation.

Figure 10.

Confocal imaging at 40X: A) BALB/c mouse challenged with Ova, B) BALB/c mouse challenged with Ova followed by treatment with budesonide 10 μM, Green: krt5, Blue: DAPI, Red: EMBP. C) Comparison of tissue eosinophil counts at 40X, cells per μm of tissue, Statistical significance between Ova challenge and Ova + Budesonide, p<0.00. Sample Size: C57BL/6 (n=4, male) and BALB/c (n=4, male)

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIEHS/NIH K23ES020859 Career Development Award

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any disclosures

References

- 1.Anand VK. Epidemiology and economic impact of rhinosinusitis. The Annals of otology, rhinology & laryngology Supplement. 2004;193:3–5. doi: 10.1177/00034894041130s502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, et al. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2003;129:S1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(03)01397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya N. Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2011;120:423–7. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Crombruggen K, Zhang N, Gevaert P, Tomassen P, Bachert C. Pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: inflammation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;128:728–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naclerio R, Blair C, Yu X, Won YS, Gabr U, Baroody FM. Allergic rhinitis augments the response to a bacterial sinus infection in mice: A review of an animal model. American journal of rhinology. 2006;20:524–33. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho SH, Oh SY, Zhu Z, Lee J, Lane AP. Spontaneous eosinophilic nasal inflammation in a genetically-mutant mouse: comparative study with an allergic inflammation model. PloS one. 2012;7:e35114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi Y, Kagawa Y, Izawa K, Ono R, Akagi M, Kamei C. Effect of histamine H4 receptor antagonist on allergic rhinitis in mice. International immunopharmacology. 2009;9:734–8. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SW, Kim JH, Jung MH, et al. Periostin may play a protective role in the development of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in a mouse model. The Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1075–81. doi: 10.1002/lary.23786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramanathan M, Jr., Turner JH, Lane AP. Technical advances in rhinologic basic science research. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2009;42:867–81. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.07.008. x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mo JH, Park SW, Rhee CS, et al. Suppression of allergic response by CpG motif oligodeoxynucleotide-house-dust mite conjugate in animal model of allergic rhinitis. American journal of rhinology. 2006;20:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalid AN, Woodworth BA, Prince A, et al. Physiologic alterations in the murine model after nasal fungal antigenic exposure. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2008;139:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KY, Nam SY, Shin TY, Park KY, Jeong HJ, Kim HM. Bamboo salt reduces allergic responses by modulating the caspase-1 activation in an OVA-induced allergic rhinitis mouse model. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 2012;50:3480–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren J, Deng Y, Xiao B, Wang G, Tao Z. Protective effects of exogenous surfactant protein A in allergic rhinitis: a mouse model. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2013;122:240–6. doi: 10.1177/000348941312200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Zhang W, Shang J, Yang J, Zhang L, Bachert C. Immunomodulatory effects of IL-23 and IL-17 in a mouse model of allergic rhinitis. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013;43:956–66. doi: 10.1111/cea.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin JH, Kim SW, Park YS. Role of NOD1-mediated signals in a mouse model of allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;147:1020–6. doi: 10.1177/0194599812461999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung HW, Jung JK, Park YK. Comparison of the efficacy of KOB03, ketotifen, and montelukast in an experimental mouse model of allergic rhinitis. International immunopharmacology. 2013;16:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K, Haczku A, Lee JJ, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW. Strain dependence of airway hyperresponsiveness reflects differences in eosinophil localization in the lung. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2001;281:L394–402. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewer JP, Kisselgof AB, Martin TR. Genetic variability in pulmonary physiological, cellular, and antibody responses to antigen in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;160:1150–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9806034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alcorn JF, Ckless K, Brown AL, et al. Strain-dependent activation of NF-kappaB in the airway epithelium and its role in allergic airway inflammation. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2010;298:L57–66. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mo JH, Lee SE, Wee JH, et al. Anti-allergic effects of So-Cheong-Ryong-Tang, a traditional Korean herbal medicine, in an allergic rhinitis mouse model. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies. 2013;270:923–30. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2152-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JH, Park HR, Kim SW, et al. The effect of topical FK506 (tacrolimus) in a mouse model of allergic rhinitis. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2012;26:e71–5. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]