Abstract

Genome editing by CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas9 (CRISPR-associated gene 9) system has been transformative in biology. Originally discovered as an adaptive prokaryotic immune system, CRISPR/Cas9 has been repurposed for genome editing in a broad range of model organisms, from yeast to mammalian cells. Protist parasites are unicellular organisms producing important human diseases that affect millions of people around the world. For many of these diseases, such as malaria, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis and cryptosporidiosis, there are no effective treatments or vaccines available. The recent adaptation of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to several protist models will be playing a key role in the functional study of their proteins, in the characterization of their metabolic pathways, and in the understanding of their biology, and will facilitate the search for new chemotherapeutic targets. In this work we review recent studies where the CRISPR/Cas9 system was adapted to protist parasites, particularly to Apicomplexans and trypanosomatids, emphasizing the different molecular strategies used for genome editing of each organism, as well as their advantages. We also discuss the potential usefulness of this technology in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Chlamydomonas, CRISPR/Cas9, genome editing, protists, trypanosomes

INTRODUCTION

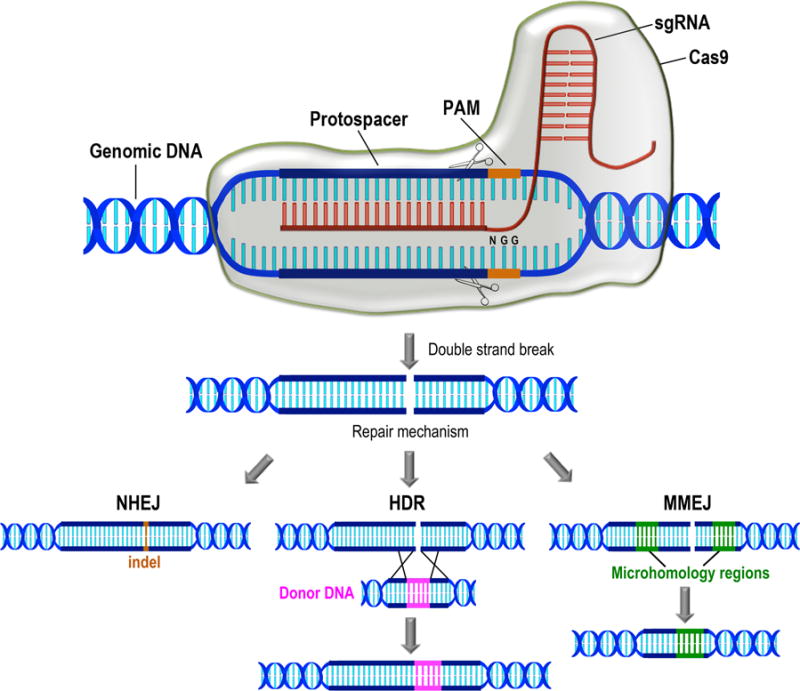

The emergence of the prokaryotic CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas9 (CRISPR-associated gene 9) system as a genome editing tool has been a revolution for the genetic manipulation of a large number of organisms, ranging from yeast to mammalian cells (Cong et al., 2013; DiCarlo et al., 2013; Gratz et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2013), and including protist parasites (Ghorbal et al., 2014; Lander et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014; Sidik et al., 2014; Sollelis et al., 2015). CRISPR/Cas9 was developed from a prokaryotic immune system used by microbes for self-defense against foreign DNA by a mechanism that efficiently records and targets viral and plasmid sequences (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010; Rath et al., 2015). Adapted for genome editing, the system consists of the prokaryotic endonuclease Cas9 and an engineered RNA chimera or single guide RNA (sgRNA) conforming a ribonucleoprotein complex able to recognize a target DNA sequence and produce double strand breaks (DSB), leading to changes in the genome sequence, which depends on the DNA repair machinery of the organism (Fig. 1) (Doudna and Charpentier, 2014). Less than four years ago, the CRISPR/Cas9 system was repurposed for sequence-specific genome editing (Jinek et al., 2012). Since then, it has been successfully used for a vast range of applications: generation of animal models (Cong et al., 2013; Gratz et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013); somatic genome editing (Schwank et al., 2013); functional genomic screening (Wang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014); regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level, either to activate genes (CRISPRa) or to repress them (CRISPRi) (Gilbert et al., 2014); correcting genetic disorders (Long et al., 2016a); treating infectious diseases (Liao et al., 2015); and more recently to edit the human germline (Liang et al., 2015), an application that has been considered by many scientists as dangerous and ethically unacceptable. Several authors have reviewed the applications of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Dominguez et al., 2016; Doudna and Charpentier, 2014; Savic and Schwank, 2016; Yang, 2015). Among the biological models where CRISPR/Cas9 has been adapted, several unicellular human pathogens such as Plasmodium falciparum, Toxoplasma gondii, Cryptosporidium parvum, Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi are particularly important, as this tool can accelerate the study of protein function and lead to the identification of chemotherapeutic targets. This is also relevant because most of these organisms lack efficient methods for reverse genetics or have been refractory to genetic manipulation (Burle-Caldas Gde et al., 2015; Docampo, 2011). Here, we review the different approaches that have been used for genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in protists, with special emphasis on human parasites.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the CRISPR/Cas9 type II system for genome editing. Cas9 and a specific sgRNA assemble together into a ribonucleoprotein complex where sgRNA targets by base pairing a specific region of the genomic DNA (protospacer). The protospacer is located immediately upstream an NGG sequence named protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Cas9 produces a double strand break at specific sites indicated by scissors on the target sequence. Further DNA repair occurs by alternative mechanisms so far described in protists. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) leads to small insertions or deletions (indels) on DNA. Homologous-directed repair (HDR) occurs in the presence of a donor DNA molecule with homology regions corresponding to sequences upstream and downstream the Cas9 cut site. Donor DNA provides a template to induce DNA repair by homologous recombination. In DNA repair by microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), end resection reveals short microhomologies on either side of the break, which are then aligned to guide repair. Repair by MMEJ always leads to deletion of the DNA sequence between the microhomologies.

CRISPR/Cas, the adaptive immune system of bacteria and archaea

CRISPR consists of a family of DNA repeats found in about 84% of archaea and 45% of bacteria according to CRISPRdb (Grissa et al., 2007; Rath et al., 2015). Although the CRISPR repeats were first observed in Escherichia coli in 1987 (Ishino et al., 1987), the acronym was used for the first time in 2002, after similar loci were found in genomic sequences from different bacteria and archaea (Jansen et al., 2002). The CRISPR array is formed by short direct repeats separated by stretches of variable sequences called spacers (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010). In 2005, three independent studies showed the existence of homology between the sequences of spacers and foreign DNA elements, such as viruses and plasmids (Bolotin et al., 2005; Mojica et al., 2005; Pourcel et al., 2005). This led for the first time to the idea that CRISPR may be a prokaryotic adaptive immune system (Mojica et al., 2005). The chronology of CRISPR discovery and its adaptation for genome editing was recently reviewed (Lander, 2016). CRISPR loci are often adjacent to CRISPR-associated (cas) genes, which encode a large protein family that carries typical domains of nucleotide-binding proteins, including nucleases (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010). CRISPR, in combination with Cas proteins, forms the CRISPR/Cas immune systems from bacteria and archaea (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010; Rath et al., 2015). The CRISPR/Cas-mediated prokaryotic immunity involves three stages: (i) Adaptation, occurs when new spacers containing foreign DNA sequences are inserted into the CRISPR locus; (ii) Expression, occurs when cas genes are expressed and the CRISPR array is transcribed into a non-processed CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA), and further processed by Cas proteins into a mature crRNA; (iii) Interference, the last stage of bacterial defense, occurs when DNA target is recognized and cleaved by a ribonucleoprotein complex conformed by crRNA and Cas proteins (reviewed by (Rath et al., 2015)). The entire process allows bacteria and archaea to get rid of foreign DNA elements in a memory-based mechanism. Three different CRISPR/Cas systems have been described based on the molecular mechanisms to achieve target DNA recognition and cleavage (Makarova et al., 2011). The type II system requires only a single Cas protein for RNA-guided DNA targeting and cleavage (Doudna and Charpentier, 2014).

The CRISPR/Cas9 type II system for genome editing

CRISPR/Cas9, a type II CRISPR system from Streptococcus pyogenes, is the most commonly used system for genome editing and has been adapted to many organisms (Doudna and Charpentier, 2014; Hsu et al., 2014; Yang, 2015). Repurposed from the prokaryotic immune system to target and cleave foreign DNA (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010; Rath et al., 2015), this system consists of an endonuclease (Cas9) and a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) duplex that targets DNA, and contains two RNA molecules: crRNA and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) (Deltcheva et al., 2011). The RNA duplex has been engineered into an RNA chimera called single guide RNA (sgRNA), for genome editing purposes (Jinek et al., 2012). The sgRNA can be programmed to target a 20-bp sequence of interest (the protospacer) by Watson-Crick base pairing (Hsu et al., 2013). The protospacer has to be located immediately upstream of a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM), an NGG sequence (where N is any nucleotide and G is the base guanine) required for S. pyogenes Cas9 recognition (Fig. 1), which represents the only constraint in the molecular design (La Russa and Qi, 2015; Zhang et al., 2014b). However, an NGG sequence can be found every 8 bp on average in the human genome (Cong et al., 2013; La Russa and Qi, 2015), making Cas9 a very flexible genetic scissors, with a specificity that does not tolerate more that 4 mismatches (Hsu et al., 2013). Two highly specific Cas9, the enhanced S. pyogenes Cas9 (eSpCa9) and the high fidelity Cas9 (Cas9-HF) that significantly reduce the possibility of producing genomic off-targeting, have been recently genetically engineered (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016) and most of the CRISPR/Cas9 systems are now being re-adapted to include such technology. The studies here reviewed involving genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in protists were performed using the original version of Cas9, as highly specific Cas9 nucleases were not available at the time.

GENOME EDITING IN APICOMPLEXANS

Apicomplexan parasites are unicellular eukaryotes characterized by the presence of an apical complex containing secretory organelles. The phylum includes causative agents of human and animal infectious diseases, such as malaria (Plasmodium spp.), toxoplasmosis (T. gondii) and cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium parvum). Malaria alone produces approximately 1 million deaths per year, while 250 million people are estimated to have this disease (Kappe et al., 2010). Cryptosporidium spp. is an important diarrhea-causing pathogen (Checkley et al., 2015), and T. gondii causes congenital disease and life-threatening infection in immunocompromised patients (Lourido and Moreno, 2015). Regarding genetic manipulation, the apicomplexan parasite for which more molecular tools have been developed is T. gondii, followed by Plasmodium spp. and most recently C. parvum, due to the adaptation of CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing to this parasite (Vinayak et al., 2015). The DSB repair mechanism exhibited by each organism is a key factor to take into account for the design of specific CRISPR/Cas9 molecular strategies. In the case of apicomplexans, the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway is present in T. gondii, but canonical components of this pathway are absent in P. falciparum, P. yoelii and C. parvum, thus DNA donor molecules to induce DSB homologous-directed repair (HDR) should be included in CRISPR/Cas9 strategies for these three organisms. In P. falciparum an alternative end-joining pathway consisting of synthesis-dependent microhomology-mediated repair was described as a mechanism involved in DSB repair (Kirkman et al., 2014). Therefore, malaria parasites utilize both homologous recombination and alternative end-joining pathways to maintain genome integrity. Here we review the experimental designs and molecular strategies used to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 system to these four Apicomplexan species. Table 1 summarizes the CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems discussed in this review.

Table 1.

Delivery systems for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in protists

| Organism | Purpose | General strategy | sgRNA transcription | DNA donor | Selective marker/reporter | DSB repair mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | Gene knockout | 2-vectors | P. falciparum U6 promoter | Yes | hdhfr or no marker | HDR | Ghorbal et al., 2014 |

| P. yoelii | Gene knockout, C-terminal tagging and insertion of point mutations | 1-vector | P. yoelii U6 promoter | Yes | hdhfr | HDR | Zhang et al., 2014 |

| P. falciparum | Gene knockout | 2-vectors | T7 promoter | Yes | T2a peptide–Renilla luciferase (T2a-RL) | HDR | Wagner et al., 2014 |

| T. gondii | Gene knockout and gene knock-in | 1-vector | T. gondii U6 promoter | Yes/No | uprt (negative selection) and GFP (Cas9 reporter), dhfr in DNA donor | NHEJ, HDR | Shen et al., 2014; Behnke et al., 2015a; Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015 |

| T. gondii | Gene knockout, C-terminal tagging and insertion of point mutations | 1-vector | T. gondii U6 promoter | Yes/No | No | NHEJ, HDR | Sidik et al., 2014 |

| T. gondii | Replacement of a complete gene tandem | 1-vector | T. gondii U6 promoter for expression of 2 sgRNAs | Yes | dhfr | HDR | Behnke et al., 2015b |

| T. gondii | Gene knockout | 1-vector | T. gondii U6 promoter | No | dhfr | NHEJ | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| C. parvum | Gene knockout and gene knock-in | 1-vector | C. parvum U6 promoter | Yes | nluc-neo | HDR | Vinayak et al., 2015 |

| T. cruzi | Single gene and multi gene family disruption; exogenous gene swapping | 1-vector | In vitro transcribed sgRNA | Yes/No | neo, bsd | MMEJ, HDR | Peng et al., 2014 |

| T. cruzi | Gene knockout (disruption and deletion) | 1-vector and 2-vectors | T. cruzi ribosomal promoter | Yes/No | neo, bsd | MMEJ, HDR | Lander et al., 2015 |

| L. major | Replacement of a complete gene tandem | 2-vectors | L. major U6 promoter | Yes | hph, pac | HDR | Sollelis et al., 2015 |

| L. donovani | Gene knockout and C-terminal tagging | 2-vectors | L. donovani ribosomal promoter | Yes/No | LdMT (negative selection) | IHR, MMEJ, HDR | Zhang et al., 2015 |

| C. reinhardtii | Gene knockout | 1-vector | Transient expression of sgRNA driven by Arabidopsis U6 promoter | No | hph and CrFKB12 (negative selection), GFP and gluc (reporters) | NHEJ | Jiang et al., 2014 |

CRISPR/Cas9 in Toxoplasma gondii

T. gondii is a human pathogen that has been extensively used as biological model within the phylum Apicomplexa for being relatively easy to culture and for the availability of molecular tools developed to genetically manipulate this organism (Sidik et al., 2014). One of the most important advances in the reverse genetics of T. gondii has been the generation of a strain deficient in the NHEJ pathway by knocking out the KU80 gene (ΔKU80 strain), thus facilitating the integration of sequences at specific loci through homologous recombination, instead of the random integration naturally observed in this parasite (Fox et al., 2009; Kirkman et al., 2014). After emerging as a tool for genome editing, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology was rapidly adapted to this organism for different purposes. In fact, the first study using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in a eukaryotic pathogen was reported in T. gondii (Shen et al., 2014), demonstrating the usefulness of this system for genetic manipulation of the laboratory RH strain and natural isolates of T. gondii bearing intact NHEJ pathway. The strategy used in this study involved a unique vector for expression of Cas9 fused to a nuclear localization signal and the green fluorescent protein (Cas9-NLS-GFP), and the specific sgRNA driven by T. gondii U6 promoter, without DNA donor, to induce DNA repair by NHEJ (see Fig. 2 for a schematic representation of different molecular strategies discussed in this review). In this work they targeted the gene encoding uracyl phosphoribosyl transferase (UPRT) in the wild-type strain RH, because its loss confers resistance to fluorodeoxyribose (FUDR). They monitored the transfection efficiency by GFP expression, finding 20–30% fluorescent cells in the population 24 h post-transfection, from which 10% were FUDR resistant, indicating inactivation of the UPRT gene. The UPRT gene from the RH strain was knocked out by replacing it with the DHFR marker through homologous recombination, by co-transfecting the plasmid carrying Cas9 and the sgRNA with linear DNA donor cassettes for gene disruption and gene replacement. The authors concluded that CRISPR/Cas9 enhances local recombination at the sgRNA target region to introduce high frequency insertions that result in gene inactivation. Finally, the authors disrupted the gene encoding ROP18 serine threonine kinase in the GT1 strain, and performed its gene complementation (gene knock-in). In this way they successfully manipulated the genome of a natural isolate of T. gondii, demonstrating the usefulness of the system in a genetic background different from that of the ΔKU80 strain.

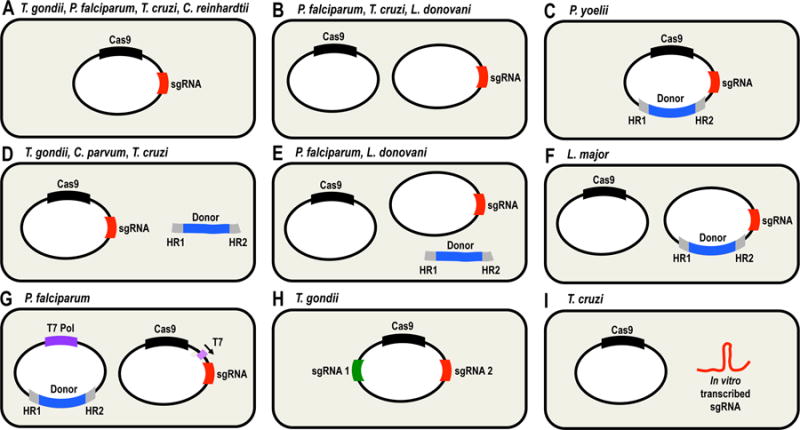

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of molecular strategies used for adapting the CRISPR/Cas9 system to different unicellular eukaryotes. A. 1-vector strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA. B. 2-vectors strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA. C. 1-vector strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA, including a DNA donor into the same vector. D. 1-vector strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA, plus a linear DNA donor. E. 2-vectors strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA, plus a linear DNA donor. F. 2-vectors strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA present in different vectors, with DNA donor included in the sgRNA vector. G. 2-vectors strategy for co-expression of T7 RNA polymerase (T7 Pol, left), Cas9 and sgRNA (right). DNA donor is included in the same vector as T7 Pol, and sgRNA transcription is driven by T7 promoter. H. 1-vector strategy for co-expression of Cas9 and two different sgRNAs. I. 1-vector strategy for expression of Cas9 and subsequent delivery of an in vitro-transcribed sgRNA. The organisms where each strategy has been used are shown on top of each panel. HR1 and HR2, homology regions present at the DNA donor cassettes to induce homologous-directed repair.

The second study where the CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used for genome editing in T. gondii was published one month later (Sidik et al., 2014). The work focused on the DNA repair mechanisms involved in the generation of mutant cell lines, and the genome editing efficiency observed depending on those mechanisms. This research group used a 1-vector strategy for cloning a Cas9-FLAG-NLS fusion protein and the specific sgRNA to transfect parasites with or without DNA donor, and induce HDR and NHEJ-mediated DNA repair, respectively. Cas9 was expressed under T. gondii tubulin promoter (pTgTUB) while sgRNA transcription was driven by TgU6 promoter. To confirm the nuclear localization of Cas9-FLAG-NLS, immunofluorescence microscopy was performed 24 h post-transfection, in parasites where the gene encoding the non-essential major tachyzoite surface protein (SAG1) was targeted. They found 20% knockout efficiency in the absence of selection while the same gene construct in ΔKU80 parasites generated 10-fold fewer knockout cells than in RH strain. When co-transfecting parasites with a DNA donor molecule, they observed 30% homologous recombination in ΔKU80 strain without selective pressure. Also, introduction of point mutations and C-terminal Ty epitope tag in TgCDPK3 gene (calcium-dependent protein kinase 3) led to 5% and 15% genome editing efficiencies in RH and ΔKU80 strain, respectively. The authors found high rates of directed genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 and were able to generate C-terminal tagged proteins in T. gondii.

Another report of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in T. gondii was published in 2015 (Zheng et al., 2015). Using a 1-vector strategy for co-expression of Cas9-FLAG-NLS fusion nuclease and a specific sgRNA to target TgLAP gene (leucine aminopeptidase) they achieved gene knockout and complementation without antibiotic selection. After these methodological reports were published, the CRISPR/Cas9 system was used in T. gondii for gene knockout and functional studies of several proteins (Behnke et al., 2015a; Behnke et al., 2015b; Long et al., 2016b; Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Behnke et al. (2015b) combined forward and reverse genetics approaches for mapping the sinefungin resistance gene (SNR1), and then they disrupted it by CRISPR/Cas9 to confirm it renders sinefungin (SFN) resistant parasites. In another work, the same group used a modified version of their T. gondii CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (Shen et al., 2014), to express two different sgRNAs that targeted regions upstream and downstream the tandem array of ROP5 genes in T. gondii genome, and completely replaced the tandem with the DHFR marker delivered in a DNA donor cassette (Behnke et al., 2015a). Wang et al. (2015) generated six knockout cell lines for calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPK4, CDPK4A, CDPK5, CDPK6, CDPK8 and CDPK9) and evaluated four phenotypic traits (invasion, egress, replication and virulence). These authors did not observe significant differences related to the parental RH strain, concluding that any of these CDPKs are essential for parasite survival. In a more recent study, genes encoding noncanonical CDPKs in type 1 and type 2 T. gondii strains, were deleted by CRISPR/Cas9 to generate 24 mutant cell lines where one or two cdpk genes have been deleted (Long et al., 2016b). Interestingly, these authors observed a phenotype in Δcdpk6 parasites, consisting in reduced ability to form plaques, a fitness defect in a competition assay, and attenuated tissue cyst formation in chronically infected mice, contrary to the absence of phenotype previously reported in Δcdpk6 parasites (Wang et al., 2015). From a methodological point of view this work (Long et al., 2016b) contributed to the improvement of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology by generating multiple cdpk gene knockouts by serial replacements through the recycling of the DHFR selectable marker, using the Cre-loxP system. This procedure led to single-drug resistant double knockout cell lines. This strategy overcomes the limited amount of selectable markers available for this organism.

Although diverse genetic tools were available for work in T. gondii before the emergence of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, genome editing using this system has significantly improved the genetic manipulation of this parasite. The fact that genome editing can be achieved in this model without DNA donor or antibiotic selection will facilitate the generation of genomic libraries for high throughput genomic screening, and we anticipate that these kind of studies will be reported soon.

CRISPR/Cas9 in Plasmodium spp

Besides the generation of conventional gene knockouts in P. falciparum, genome editing has been successfully achieved in this parasite using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology (Straimer et al., 2012). Thereafter, the first report of genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in this pathogen was published by (Ghorbal et al., 2014). In this study the authors designed a 2-vector strategy, co-transfecting asexual blood-stage parasites with an episomal vector for the expression of Cas9 (plasmid pUF1-Cas9) and a second expression vector carrying the sgRNA sequence and a DNA donor (plasmid pL7) to induce DNA repair by HDR, as P. falciparum lacks the canonical NHEJ pathway. In this molecular design, they used a P. falciparum U6 small nucleolar RNA regulatory element to transcribe the sgRNA by RNA polymerase III. In this way, they disrupted an exogenous gene (egfp) encoding the enhanced green fluorescent protein, and an endogenous non-essential gene (kharp) encoding the knob-associated histidine-rich protein. The authors tested two delivery strategies (circular and linear) for vector pL7, leading to similar results in terms of transfection efficiency. However, using linear pL7 resulted in an easier approach as it avoids the need for negative selection against parasites retaining the plasmid. Disruption of egfp and kharp with human dihydrofolate reductase (hdhfr) gene was achieved by selection of drug-resistant parasites that were recovered within 1–3 weeks post-transfection. They also introduced a single-point “shield” mutation into kharp gene without integration of a selectable marker. The shield mutation was a silent mutation at the protospacer that abolished recognition of Cas9. In this case transfectant parasites were also observed within 3 weeks, which represented a significant improvement over conventional knockout methods in P. falciparum requiring at least 2–4 months for the generation of double resistant null mutants.

A second study of genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 was performed in another member of the genus Plasmodium (Zhang et al., 2014a), where authors adapted the prokaryotic system to P. yoelii—a rodent pathogen—using a drug-resistance marker cassette to induce DNA repair by homologous recombination, and generate mutant cell lines for gene deletion, endogenous C-terminal tagging, allelic replacement, and simultaneous insertion of a point mutation plus a silent shield mutation. Here they used a 1-vector strategy, with the sequences of Cas9, sgRNA and DNA donor cloned into the same plasmid (pYC). The sgRNA sequence was transcribed by RNA polymerase III using P. yoelii U6 promoter, achieving 100% efficiency in the deletion of Pysera1 and Pysera2 genes, encoding non-essential serine proteases. They also replaced PyPDH/E1α gene, encoding the E1α subunit of P. yoelii pyruvate dehydrogenase, which is required for parasite development in the liver, leading to 100% gene deletion in mixed populations. However, in knock-in experiments to generate GFP C-terminal tagged proteins, the genome editing efficiency dropped to 22% and 44%, an observation for which they could not find an explanation. Similar results were obtained in single nucleotide replacement, where 25% editing efficiency was achieved. In general this work explored the usefulness of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for most of the applications known at that time for genome editing in other organisms.

Another group reported genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in P. falciparum (Wagner et al., 2014). This group developed a T7 promoter-driven system to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to this parasite. To achieve this goal, they designed a 2-vector strategy: plasmid pT7 RNAP-HR for expression of T7 RNA polymerase and delivery of a DNA donor cassette for DSB repair by homologous recombination; and plasmid pCas9-sgRNA-T for expression of Cas9 and sgRNA to target a specific locus. Using this system the authors observed deletion of kharp gene at day 33 post-transfection. They also performed deletion of eba-175 gene, which encodes a parasite ligand necessary for invasion of red blood cells. The overall editing efficiency achieved in this work was between 50% and 100%, confirming previous observations that genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in Plasmodium spp. is feasible and highly efficient. A similar strategy was recently used to insert point mutations in P. falciparum transporter PfMDR1 (multi drug resistance 1) and evaluate resistance to the piperazine-containing compound ACT-451840 (Ng et al., 2016).

Recently, another strategy for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in P. falciparum has been reported, in which 2 vectors where used for gene knockout/knock-in using what they called a suicide-rescue system (Lu et al., 2016). One of the vectors allows the expression of Cas9 and sgRNA driven by endogenous promoters, while a second vector was used for the transient delivery of a marker-free DNA donor to induce HDR. Using this system the authors were able to disrupt the Pfset2 gene and to insert a green fluorescent protein-renilla luciferase (gfp-ruc) fusion gene into the Pf47 locus in P. falciparum. They claimed this system requires fewer selectable markers and exhibits potential for large sequence knock-ins.

In general, the development of different strategies to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing to Plasmodium spp. represents a significant improvement in the reverse genetics of these pathogens that have been particularly refractory to genetic manipulation. The use of these methodologies for functional studies in P. falciparum is promising in terms of treatment and vaccine development against malaria.

CRISPR/Cas9 in Cryptosporidium parvum

Cryptosporidium has gained importance within the phylum Apicomplexa because recent reports identified it as the second most important pathogen causing diarrhea after rotavirus (Checkley et al., 2015; Kotloff et al., 2013; Mondal et al., 2012). There is no vaccine against this parasite and the only available treatment is not effective in immunocompromised patients (Sparks et al., 2015). In general, the development of efficient treatments or vaccines to prevent Cryptosporidium infections has been lagging behind other aplicomplexan pathogens due to the lack of culture methods, the absence of animal models to emulate its life cycle and the lack of molecular tools for its genetic manipulation. A recent study in C. parvum achieved the goal of establishing all three missing aspects necessary for laboratory research with this parasite (Vinayak et al., 2015). In this work, the authors described methods for laboratory culture, mouse infection and genetic manipulation of this pathogen, including transfection methods, selection of an efficient antibiotic resistance marker, identification of strong gene promoters, codon optimization, selection of an appropriate expression reporter and adaptation of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing to C. parvum. As the NHEJ pathway is absent in this parasite, they developed a 1-vector strategy for expression of sgRNA and Cas9 nuclease driven by C. parvum U6 RNA promoter and parasite regulatory sequences, and then co-transfected it with a DNA donor for homologous recombination. To test the system, they used a DNA template to repair the sequence of an inactive nanoluciferase (dead Nluc), thus restoring the open reading frame and the function of the reporter. In this way, the authors used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to genetically manipulate for the first time C. parvum opening up a range of possibilities for target validation and the study of physiological processes in this important pathogen.

GENOME EDITING IN TRYPANOSOMATIDS

Trypanosomatids (order Kinetoplastida) include human pathogens T. brucei and T. cruzi, the causative agents of African and American trypanosomiasis, respectively, and Leishmania spp., etiologic agents of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis. These are diseases spread all over the world. All these human pathogens are mainly diploid and lack introns, which facilitates in silico analyses of their genomic sequences (Burle-Caldas Gde et al., 2015; Docampo, 2011). Genetic manipulation of these parasites has been mainly performed in T. brucei, where the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery is present and allows downregulation of specific targets. Homologous recombination can be used for efficient gene knockout in T. brucei, although two rounds of replacement with two different resistance markers are necessary to disrupt both alleles of a gene (Docampo, 2011). However, the RNAi machinery is absent in T. cruzi and present in just a few species of Leishmania (Kolev et al., 2011), and few conventional gene knockouts have been reported in both parasites. Conditional knockouts have been generated in T. brucei, while systems for tetracycline-inducible and constitutive expression are available in all three species (Docampo, 2011). In general, the toolbox available for genetic manipulation of T. cruzi and Leishmania spp. is more limited than in T. brucei, thus reducing the functional study of proteins in these parasites. Fortunately, genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 has been recently achieved in T. cruzi, L. major and L. donovani (Lander et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015; Sollelis et al., 2015; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015), as reviewed below.

Trypanosoma cruzi

The first study involving genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in T. cruzi (Peng et al., 2015) was performed using a 1-vector strategy to generate a mutant cell line that constitutively expresses Cas9, where an in vitro transcribed sgRNA molecule was delivered by electroporation with or without a DNA donor molecule for HDR. In the absence of DNA donor, these authors demonstrated by whole-genome sequencing that DNA repair in T. cruzi was carried out by microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ). This repair mechanism was previously described in T. brucei (Glover et al., 2011; Glover et al., 2008), leading to small deletions at the DSB region, but has not been fully investigated in T. cruzi. The result is consistent with the absence of NHEJ pathway in trypanosomatids. Interestingly, they observed a cytotoxic effect of Cas9 expression in mutant parasites, which could explain the low efficiency rates for genome editing reported in this work, that were even lower when using a DNA donor molecule to induce exogenous gene exchange (0.11% and 0.069% swap of GFP for tdTomato fluorescence). Using the CRISPR/Cas9 system without DNA donor, they targeted endogenous genes encoding putative fatty acid transporter (FATP), and histidine ammonia lyase (HAL), and found a decrease in their activities when compared to wild type parasites. However, the authors did not show additional evidence of disruption of these two genes other than the activity assays. An important contribution of this work was the use of CRISPR/Cas9 to downregulate the expression of a gene family of 65 members with 93% sequence homology (β-galactofuranosyl glycosyltransferase, β-GalGT), confirmed by whole-genome sequencing. The authors found that sixty three percent of the genes exhibited a deletion in at least one out of three targeted sites. This strategy could be useful for the generation of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout libraries and for downregulation of conserved gene families.

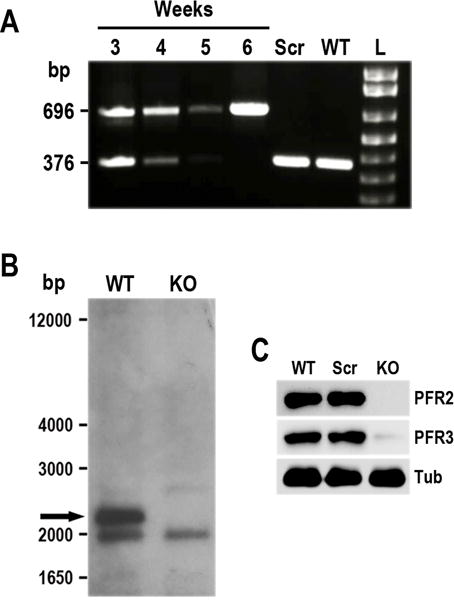

A few months later our research group reported a different approach to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 system to T. cruzi. As a proof of concept we used three different strategies to disrupt endogenous genes, for which knockout phenotypes were well described and not expected to be lethal. Using either 1-vector or 2-vector strategies for constitutive expression of sgRNA and Cas9 driven by the ribosomal promoter, or one vector containing sgRNA and Cas9 (plasmid Cas9/pTREX-n) plus a DNA donor cassette for homologous recombination, we were able to generate mutant cell lines in which paraflagellar rod proteins 1 (PFR1) and 2 (PFR2), and gp72 genes were disrupted. Phenotypic analysis revealed that all these proteins contribute to flagellar attachment to the cell body and parasite motility (See Movies 1 and 2 in Supporting Information). Additionally, PFR1 and PFR2 are involved in assembly of the paraflagellar rod structure, as evidenced by western blot analysis and transmission electron microscopy. The co-transfection of Cas9/pTREX-n vector carrying the sgRNA, and a DNA donor to induce DSB repair by homologous recombination on the PFR2 locus, increased the genome editing efficiency to 100%, leading to the generation of a homogeneous knockout population in just five weeks, a result that was not previously achieved in T. cruzi. Time course PCR analysis demonstrated the sequential replacement of both alleles by the same resistance marker along six weeks (Fig. 3A), as well as the deletion of the PFR2 gene in the entire population as shown by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 3B). We further confirmed the disassembly of the paraflagellar rod structure in PFR2-KO epimastigotes by western blot analysis using antibodies anti TcPFR2 and TcPFR3, kindly provided by Dr. Manuel C. Lopez (Egui et al., 2012). Our results indicate that PFR2 is absent in this mutant cell line, while the expression of PFR3 is significantly reduced (Fig. 3C). Our work reported for the first time the generation of a clean gene knockout by CRISPR/Cas9 in T. cruzi, as well as the induction of DSB repair by HDR using 100-bp homology arms in the DNA donor cassette, demonstrating that this length is sufficient to produce homologous recombination in this parasite. In addition, we did not observe any toxicity from Cas9 using this method. We anticipate that this method will allow the generation of endogenous C-terminal tagging and gene knock-in in this almost intractable parasite.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of PFR2-KO cell line in T. cruzi. A. Time course PCR analysis of TcPFR2-KO epimastigotes at weeks 3–6 post-transfection. Disruption of the TcPFR2 gene was verified by PCR with primers annealing outside the homology regions on the blasticidin cassette (Lander et al., 2015). A fragment of 696 bp was amplified from gDNA isolated from the TcPFR2-KO mutant, indicating disruption of the PFR2 gene. The same primer set generates a fragment of 376 bp in the original locus. Notice that the band corresponding to the intact locus (376 bp) disappears with time, being undetectable at 5 weeks post-transfection. Epimastigotes expressing Cas9 and a scrambled sgRNA (Scr), and wild type (WT) epimastigotes were included in the analysis as control cell lines. L, 1 kb plus ladder (Invitrogen). B. Southern blot analysis of wild type (WT) and TcPFR2-KO (KO) epimastigotes. gDNA was digested with StuI/XhoI restriction enzymes and then used for Southern blot analysis using a 500-bp TcPFR2 probe. The band corresponding to TcPFR2 (pointed out with black arrow) is present in WT parasites and absent in KO epimastigotes. Molecular weights (bp) are shown on the left side. C. Western blot analysis of control and TcPFR2-KO epimastigotes. Total lysates (20 μg/lane) of wild-type (WT), scrambled control (Scr), and TcPFR2-KO epimastigotes (KO) were analyzed by Western blot with polyclonal antibodies anti T. cruzi PFR2 and PFR3 (Egui et al., 2012). Anti-β-tubulin antibody (Tub) was used as loading control.

Leishmania spp.

The adaptation of CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing in Leishmania major was summarized in a recent report (Sollelis et al., 2015). These authors developed a 2-vector strategy in which one vector allowed the expression of Cas9 nuclease and the other one the sgRNA driven by the U6 promoter plus a DNA donor molecule. They targeted the entire PFR2 tandem, which exhibits three gene copies in L. major. The phenotypic analysis of the knockout cell line was performed by PCR, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), western blot analysis, fluorescence microscopy and whole genome sequencing. The last method was used to rule out the presence of off-target effects. The protein was absent in PFR2 knockout parasites and in contrast to what we observed in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015), the genome editing with DNA donor was not 100% efficient. In this regard, the authors explained that the generation of mixed populations is commonly seen in Leishmania when episomal vectors are used. This work shows strong evidence of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in L. major.

A more extensive work using the CRISPR/Cas9 system was performed in L. donovani (Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015), using a 2-vector strategy, in which one expression vector contains the sequence of Cas9 and the other one carried the sgRNA sequence transcribed by the ribosomal promoter (sRNAP). They tested two different versions of this second vector. The first one included the sequence of the Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) ribozyme downstream of the sgRNA to avoid polyadenylation of the sgRNA and ensure its proper length (plasmid pSPneogRNAH). An alternative version of this plasmid did not carry the ribozyme sequence. They used both vectors to generate knockout and endogenous C-terminal tagging (with a GFP tag) of the gene encoding miltefosine transporter (LdMT). Ablation of LdMT leads to miltefosine (MLF) resistant parasites. Miltefosine is the only available oral anti-leishmanial drug. They found that presence of the ribozyme downstream the sgRNA sequence actually increased the percentage of MLF resistant parasites after 6 weeks of transfection (12%) compared to the amount of resistant cells observed in the absence of ribozyme (6%). However, as observed in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015), a functional sgRNA could be generated in the absence of a downstream ribozyme when the expression of the sgRNA is driven by the ribosomal promoter, although the post-transcriptional processing of this sgRNA occurs through an unknown mechanism in both T. cruzi and L. donovani. They also tested a vector carrying 2 sgRNAs to increase the disruption efficiency of LdMT gene, finding that this strategy was 4-fold more efficient than using a unique sgRNA for gene knockout by MMEJ, without DNA donor. To generate LdMT-KO parasites by HDR these authors employed a different strategy, which involved the use of 61-nt oligonucleotides containing 3 stop codons flanked by 25-nt homology regions corresponding to the sequences located immediately upstream and downstream the Cas9 cut site on the LdMT ORF. All the experiments involving gene disruption by homologous recombination were performed without antibiotic selection and successfully generated knockout cell lines, demonstrating in this way the versatility of the system. Sequence analysis of disrupted genes in the absence of oligonucleotides for HDR led to the conclusion that DSBs in L. donovani are mainly repaired by interchromosomal homologous recombination and secondarily by MMEJ, while no NHEJ was detected, as occurs in other trypanosomatids. However, providing oligonucleotides to induce DSB repair by homologous recombination, significantly increased the efficiency of gene disruption, as observed in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015). In this way, the experimental design used by (Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015) provided strong evidence about the DSB repair mechanisms in L. donovani.

CRISPR/Cas9 IN THE GREEN ALGAE Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

The CRISPR/Cas9 technology has also been adapted to C. reinhardtii, a unicellular green algae that is the only non-pathogenic protist we are including in this review for being an excellent biological model to study photosynthesis, cell motility and many other metabolic pathways. Moreover, C. reinhardtii is an haploid organism easy to culture, with a fully annotated genome, for which classical tools for genetic manipulation has been developed (Jinkerson and Jonikas, 2015). Also, the presence of the RNAi machinery and the NHEJ pathway in this organism makes possible to perform gene silencing by RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing without DNA donor. However, there is only one report of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in this alga (Jiang et al., 2014). Based on the initial observation that Cas9 is cytotoxic when constitutively expressed in C. reinhardtii, in this work the authors tested the transient expression of both, a codon optimized Cas9 and sgRNA inserted into one single vector, to evaluate genome editing at 24 h post-transfection without providing a DNA donor cassette for homologous recombination. Using this system they targeted 3 exogenous genes: a hygromycin resistance gene, a mutant shifted-frame GFP gene and a mutant Gaussia luciferase Gluc gene. They also targeted an endogenous C. reinhardtii gene (FKB12) that confers sensitivity to rapamycin. The four targeted genes were used in experiments designed to test the generation of mutagenized target DNA sequences by rendering hygromycin resistance, green fluorescence, luminescence and rapamycin resistance, respectively. After selection of mutant colonies, gDNA was isolated and regions containing the sgRNA target sites were PCR amplified and analyzed by digestion with restriction enzymes and DNA sequencing. For all the genes targeted, the authors achieved the goal of generating mutant cell lines by transient expression of Cas9 and a specific sgRNA, and by repairing Cas9-induced DSBs through the NHEJ pathway. Although the authors did not perform the phenotypic characterization of mutant cell lines or explored the possibility of using a DNA donor for HDR, they showed an easy alternative for genetic manipulation of C. reinhardtii.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

The simplicity and versatility of the CRISPR/Cas9 system makes it a powerful tool for genome editing and modulation of gene expression over previously developed technologies such as TALEN (transcription activator-like effectors), ZFN (zinc finger nuclease), and RNAi. This two-component system (Cas9-sgRNA) has been easily adapted to many biological models, including protist parasites that are causative agents of important diseases affecting millions of people around the world. In this review we have described the different strategies used to adapt this technology to the most representative protist models, with the ultimate goal of studying biological processes that are absent in other eukaryotic cells, thus facilitating the search for alternative therapies to fight the diseases they produce.

Contrary to what is possible to do by RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing is not limited to loss-of-function studies (gene deletion/disruption/mutation) but could also be used for the insertion of specific exogenous sequences (gene knock-in, C-terminal tagging), genome-wide screening, and regulation of gene expression (CRISPRi, CRISPRa). Most of the studies conducted in protist parasites and the green algae C. reinhardtii have been performed to demonstrate the applicability of the technique to each model, and all of them were done to produce knockout cell lines and in some cases C-terminal tagged proteins. The generation of CRISPR libraries has not been explored yet in protists. We believe this approach is particularly feasible in organisms where the NHEJ repair pathway is present, such as T. gondii and C. reinhardtii. In the absence of NHEJ, the incorporation of a DNA donor for HDR into the system significantly increased the genome editing efficiency (Lander et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014; Sidik et al., 2014; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015). So, a more elaborated experimental design including multiple sgRNA and multiple DNA donor delivery methods has to be developed for genome-wide screening in these organisms.

The Cas9 off-targeting is defined by its tolerance to mismatches in the protospacer sequence (Doudna and Charpentier, 2014). Although several algorithms have been developed to predict optimal sgRNA sequences in protists (Peng et al., 2015; Sidik et al., 2014), the recent emergence of highly efficient Cas9 nucleases (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016) makes imperative the inclusion of either eSpCas9 or Cas9-HF into the CRISPR/Cas9 systems developed in different model organisms, including unicellular eukaryotes. This approach will avoid the need of genome screening for off-targeting sites during the design of programmable sgRNAs.

Among the CRISPR/Cas9 applications that can be achieved in protist parasite models, the development of inducible systems is very promising for the functional study of essential genes. Up to now, stable and transient expression systems have been tested in protist parasites, but there are no reports of inducible expression of either Cas9 or sgRNA in these organisms. An inducible CRISPR/Cas9 system could make feasible the generation of conditional knockouts that, except in T. gondii and T. brucei, have not been reported in most of the protist parasite models here described. Also, the use of a CRISPR/Cas9 system for RNA targeting and cleavage (O’Connell et al., 2014) would be very useful for regulation of gene expression in these organisms, particularly in trypanosomes where polycistronic transcription hampers the use of inactive Cas9 (dCas9) for regulatory purposes (CRISPRi, CRISPRa).

It is relevant to mention the importance of genome editing in protist parasites that has been historically refractory to genetic manipulation, such as P. falciparum and T. cruzi. Commonly used genetic strategies such as C-terminal tagging and conditional knockouts have not been reported in these parasites yet. The availability of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in these organisms opens a broad range of possibilities to perform genetic manipulation and functional studies on them. For example, the report of multi gene family disruption in T. cruzi (Peng et al., 2015) is a very promising approach to study surface protein families involved in host cell invasion and evasion of the immune system, such as trans-sialidases and mucin-associated surface proteins (MASP).

Finally, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology promises to change the pace and course of physiological studies in protist parasites, thus accelerating the chances of finding new drug targets, more efficient chemotherapies and the development of vaccines to overcome current mortality and morbidity rates reported for the diseases that these organisms produce.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1. Cell motility of T. cruzi wild type epimastigotes. Live imaging of T. cruzi (Y strain) wild type epimastigotes in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium was recorded during 22 s under differential interference contrast (DIC). Movie was captured in an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ charge-coupled device camera driven by DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA).

Movie 2. Cell motility of T. cruzi PFR2-KO epimastigotes. Live imaging of T. cruzi (Y strain) PFR2-KO epimastigotes in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium was recorded during 22 s under differential interference contrast (DIC). Notice the detached flagella and the defect in forward cell motility exhibited by these parasites. Movie was captured in an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ charge-coupled device camera driven by DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA).

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the Sāo Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil (2013/50624-0) and the U. S. National Institutes of Health (grant AI107663). N.L. and M.A.C. are postdoctoral fellows of FAPESP (2014/08995-4 and 2014/13148-9).

LITERATURE CITED

- Behnke MS, Khan A, Lauron EJ, Jimah JR, Wang Q, Tolia NH, Sibley LD. Rhoptry Proteins ROP5 and ROP18 Are Major Murine Virulence Factors in Genetically Divergent South American Strains of Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Genet. 2015a;11:e1005434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke MS, Khan A, Sibley LD. Genetic mapping reveals that sinefungin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii is controlled by a putative amino acid transporter locus that can be used as a negative selectable marker. Eukaryot Cell. 2015b;14:140–148. doi: 10.1128/EC.00229-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burle-Caldas Gde A, Grazielle-Silva V, Laibida LA, DaRocha WD, Teixeira SM. Expanding the tool box for genetic manipulation of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2015;203:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkley W, White AC, Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM, Fayer R, Griffiths JK, Guerrant RL, Hedstrom L, Huston CD, Kotloff KL, Kang G, Mead JR, Miller M, Petri WA, Jr, Priest JW, Roos DS, Striepen B, Thompson RC, Ward HD, Van Voorhis WA, Xiao L, Zhu G, Houpt ER. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltcheva E, Chylinski K, Sharma CM, Gonzales K, Chao Y, Pirzada ZA, Eckert MR, Vogel J, Charpentier E. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature. 2011;471:602–607. doi: 10.1038/nature09886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4336–4343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R. Molecular parasitology in the 21st century. Essays Biochem. 2011;51:1–13. doi: 10.1042/bse0510001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez AA, Lim WA, Qi LS. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:5–15. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egui A, Thomas MC, Morell M, Maranon C, Carrilero B, Segovia M, Puerta CJ, Pinazo MJ, Rosas F, Gascon J, Lopez MC. Trypanosoma cruzi paraflagellar rod proteins 2 and 3 contain immunodominant CD8(+) T-cell epitopes that are recognized by cytotoxic T cells from Chagas disease patients. Mol Immunol. 2012;52:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox BA, Ristuccia JG, Gigley JP, Bzik DJ. Efficient gene replacements in Toxoplasma gondii strains deficient for nonhomologous end joining. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:520–529. doi: 10.1128/EC.00357-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbal M, Gorman M, Macpherson CR, Martins RM, Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ. Genome editing in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:819–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, Guimaraes C, Panning B, Ploegh HL, Bassik MC, Qi LS, Kampmann M, Weissman JS. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover L, Jun J, Horn D. Microhomology-mediated deletion and gene conversion in African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1372–1380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover L, McCulloch R, Horn D. Sequence homology and microhomology dominate chromosomal double-strand break repair in African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2608–2618. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, O’Connor-Giles KM. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–1035. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W52–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science. 2010;327:167–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1179555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, Cradick TJ, Marraffini LA, Bao G, Zhang F. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5429–5433. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Brueggeman AJ, Horken KM, Plucinak TM, Weeks DP. Successful transient expression of Cas9 and single guide RNA genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13:1465–1469. doi: 10.1128/EC.00213-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Zhou H, Bi H, Fromm M, Yang B, Weeks DP. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinkerson RE, Jonikas MC. Molecular techniques to interrogate and edit the Chlamydomonas nuclear genome. Plant J. 2015;82:393–412. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappe SH, Vaughan AM, Boddey JA, Cowman AF. That was then but this is now: malaria research in the time of an eradication agenda. Science. 2010;328:862–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1184785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman LA, Lawrence EA, Deitsch KW. Malaria parasites utilize both homologous recombination and alternative end joining pathways to maintain genome integrity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:370–379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Joung JK. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolev NG, Tschudi C, Ullu E. RNA interference in protozoan parasites: achievements and challenges. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:1156–1163. doi: 10.1128/EC.05114-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Zaidi AK, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ochieng JB, Omore R, Oundo JO, Hossain A, Das SK, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Adegbola RA, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Akinsola A, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acacio S, Biswas K, O’Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Berkeley LY, Muhsen K, Sommerfelt H, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Russa MF, Qi LS. The New State of the Art: Cas9 for Gene Activation and Repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3800–3809. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00512-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 2016;164:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Li ZH, Niyogi S, Docampo R. CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Disruption of Paraflagellar Rod Protein 1 and 2 Genes in Trypanosoma cruzi Reveals Their Role in Flagellar Attachment. MBio. 2015;6:e01012. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01012-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, Lv J, Xie X, Chen Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Bai Y, Songyang Z, Ma W, Zhou C, Huang J. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2015;6:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HK, Gu Y, Diaz A, Marlett J, Takahashi Y, Li M, Suzuki K, Xu R, Hishida T, Chang CJ, Esteban CR, Young J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system as an intracellular defense against HIV-1 infection in human cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6413. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C, Amoasii L, Mireault AA, McAnally JR, Li H, Sanchez-Ortiz E, Bhattacharyya S, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016a;351:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S, Wang Q, Sibley LD. Analysis of Noncanonical Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases in Toxoplasma gondii by Targeted Gene Deletion Using CRISPR/Cas9. Infect Immun. 2016b;84:1262–1273. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01173-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourido S, Moreno SN. The calcium signaling toolkit of the Apicomplexan parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium spp. Cell Calcium. 2015;57:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Tong Y, Pan J, Yang Y, Liu Q, Tan X, Zhao S, Qin L, Chen X. A redesigned CRISPR/Cas9 system for marker-free genome editing in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:198. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1487-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Wolf YI, Yakunin AF, van der Oost J, Koonin EV. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal D, Minak J, Alam M, Liu Y, Dai J, Korpe P, Liu L, Haque R, Petri WA., Jr Contribution of enteric infection, altered intestinal barrier function, and maternal malnutrition to infant malnutrition in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:185–192. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CL, Siciliano G, Lee MC, de Almeida MJ, Corey VC, Bopp SE, Bertuccini L, Wittlin S, Kasdin RG, Le Bihan A, Clozel M, Winzeler EA, Alano P, Fidock DA. CRISPR-Cas9-modified pfmdr1 protects Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages and gametocytes against a class of piperazine-containing compounds but potentiates artemisinin-based combination therapy partner drugs. Mol Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/mmi.13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell MR, Oakes BL, Sternberg SH, East-Seletsky A, Kaplan M, Doudna JA. Programmable RNA recognition and cleavage by CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2014;516:263–266. doi: 10.1038/nature13769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D, Kurup SP, Yao PY, Minning TA, Tarleton RL. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated single-gene and gene family disruption in Trypanosoma cruzi. MBio. 2015;6:e02097–02014. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02097-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology. 2005;151:653–663. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath D, Amlinger L, Rath A, Lundgren M. The CRISPR-Cas immune system: biology, mechanisms and applications. Biochimie. 2015;117:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugarabamu G, Marq JB, Guerin A, Lebrun M, Soldati-Favre D. Distinct contribution of Toxoplasma gondii rhomboid proteases 4 and 5 to micronemal protein protease 1 activity during invasion. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97:244–262. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic N, Schwank G. Advances in therapeutic CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Transl Res. 2016;168:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, Nieuwenhuis EE, Beekman JM, Clevers H. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Brown KM, Lee TD, Sibley LD. Efficient gene disruption in diverse strains of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/CAS9. MBio. 2014;5:e01114–01114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidik SM, Hackett CG, Tran F, Westwood NJ, Lourido S. Efficient genome engineering of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker IM, Gao L, Zetsche B, Scott DA, Yan WX, Zhang F. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016;351:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollelis L, Ghorbal M, MacPherson CR, Martins RM, Kuk N, Crobu L, Bastien P, Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ, Sterkers Y. First efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Leishmania parasites. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:1405–1412. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks H, Nair G, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, White AC., Jr Treatment of Cryptosporidium: What We Know, Gaps, and the Way Forward. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s40475-015-0056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straimer J, Lee MC, Lee AH, Zeitler B, Williams AE, Pearl JR, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Llinas M, Urnov FD, Fidock DA. Site-specific genome editing in Plasmodium falciparum using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Methods. 2012;9:993–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinayak S, Pawlowic MC, Sateriale A, Brooks CF, Studstill CJ, Bar-Peled Y, Cipriano MJ, Striepen B. Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature. 2015;523:477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JC, Platt RJ, Goldfless SJ, Zhang F, Niles JC. Efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Methods. 2014;11:915–918. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Huang SY, Li TT, Chen K, Ning HR, Zhu XQ. Evaluation of the basic functions of six calcium-dependent protein kinases in Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR-Cas9 system. Parasitol Res. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Peng ED, Huang AS, Xia D, Vermont SJ, Lentini G, Lebrun M, Wastling JM, Bradley PJ. Identification of Novel O-Linked Glycosylated Toxoplasma Proteins by Vicia villosa Lectin Chromatography. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Wei JJ, Sabatini DM, Lander ES. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science. 2014;343:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1246981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome engineering. Mil Med Res. 2015;2:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-015-0038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Xiao B, Jiang Y, Zhao Y, Li Z, Gao H, Ling Y, Wei J, Li S, Lu M, Su XZ, Cui H, Yuan J. Efficient editing of malaria parasite genome using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. MBio. 2014a;5:e01414–01414. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01414-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wen Y, Guo X. CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: progress, implications and challenges. Hum Mol Genet. 2014b;23:R40–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WW, Matlashewski G. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Leishmania donovani. MBio. 2015;6:e00861. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00861-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Jia H, Zheng Y. Knockout of leucine aminopeptidase in Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhu S, Cai C, Yuan P, Li C, Huang Y, Wei W. High-throughput screening of a CRISPR/Cas9 library for functional genomics in human cells. Nature. 2014;509:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature13166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1. Cell motility of T. cruzi wild type epimastigotes. Live imaging of T. cruzi (Y strain) wild type epimastigotes in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium was recorded during 22 s under differential interference contrast (DIC). Movie was captured in an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ charge-coupled device camera driven by DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA).

Movie 2. Cell motility of T. cruzi PFR2-KO epimastigotes. Live imaging of T. cruzi (Y strain) PFR2-KO epimastigotes in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium was recorded during 22 s under differential interference contrast (DIC). Notice the detached flagella and the defect in forward cell motility exhibited by these parasites. Movie was captured in an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ charge-coupled device camera driven by DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA).