Abstract

Objective

To investigate the length of hospital stay (LOS) after stroke using the database of the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service.

Methods

We matched the data of patients admitted for ischemic stroke onset within 7 days in the Departments of Neurology of 12 hospitals to the data from the database of the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. We recruited 3,839 patients who were hospitalized between January 2011 and December 2011, had a previous modified Rankin Scale of 0, and no acute hospital readmission after discharge. The patients were divided according to the initial National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score (mild, ≤5; moderate, >5 and ≤13; severe, >13); we compared the number of hospitals that admitted patients and LOS after stroke according to severity, age, and sex.

Results

The mean LOS was 115.6±219.0 days (median, 19.4 days) and the mean number of hospitals was 3.3±2.1 (median, 2.0). LOS was longer in patients with severe stroke (mild, 65.1±146.7 days; moderate, 223.1±286.0 days; and severe, 313.2±336.8 days). The number of admitting hospitals was greater for severe stroke (mild, 2.9±1.7; moderate, 4.3±2.6; and severe, 4.5±2.4). LOS was longer in women and shorter in patients less than 65 years of age.

Conclusion

LOS after stroke differed according to the stroke severity, sex, and age. These results will be useful in determining the appropriate LOS after stroke in the Korean medical system.

Keywords: Length of stay, Stroke, Database, Patient acuity

INTRODUCTION

Korean stroke patients in the acute stage tend to delay discharge or request transfer to another hospital instead of home discharge [1,2]. The increased length of hospital stay (LOS), which is based on socio-economic factors (such as caregiver burden) rather than medical conditions, could hamper home and societal reintegration and increase the disease burden on society. To implement adequate medical service delivery policy after stroke, a thorough analysis of LOS from admission in acute care hospitals to home discharge is necessary. Although a population-based study reported that the mean LOS after stroke was 191.5 days, the authors analyzed only 77 community-dwelling survivors after brain disease who were registered in the Korean registry for persons with disabilities [3]. Additionally, the authors did not report the LOS according to the severity of stroke.

Because the admission period including rehabilitation could vary considerably depending on the severity of stroke, stroke severity should be considered when investigating LOS [4,5,6]. In this study, we investigated the LOS and the number of hospitals that admitted patients after onset according to the severity of the stroke, which was classified according to the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [7].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

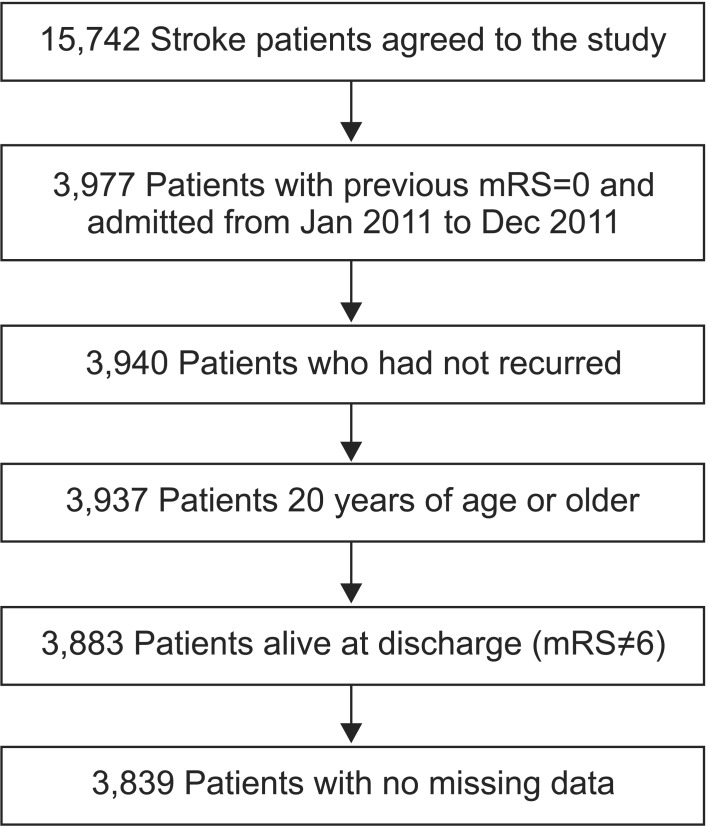

We utilized the prospective cohort dataset used in the Multicenter Prospective Observational Study about Recurrence and its Determinants after Acute Ischemic Stroke (MOSAIC) study. The dataset was prepared by neurologists from 12 university hospitals in Korea from 2009, and hospitalized patients admitted for ischemic stroke onset within 7 days were included in the dataset. Between January 2009 and November 2013, 15,742 patients who were admitted for ischemic stroke in the hospitals and who agreed to be enrolled in the study were registered. We recruited 3,839 patients who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) hospitalization between January 2011 and December 2011, (2) first stroke (i.e., previous modified Rankin Scale [mRS] of 0), (3) no experience of acute hospital readmission after discharge, (4) age >19 years, and (5) survival after stroke (i.e., mRS at discharge from the first hospital ≠6) (Fig. 1). The variables extracted from the database were registration identification number; registered hospital identification number; sex; age; onset date; discharge date; initial mRS score and evaluation date; previous mRS score; discharge mRS score and evaluation date; initial and discharge NIHSS scores and evaluation dates; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision code for stroke (from I60–I69); and occurrence of cardiovascular disease including stroke and myocardial infarction after registration. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Bundang Seoul National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea (IRB No. B-1508/310-114).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of subject recruitment. mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Data linkage

Extracted data from MOSAIC were linked with the database of the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Researchers can only access the outputs in a secure environment, which has restricted access. Linked variables from the database of the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service were hospital numbers after stroke, LOS in each hospital, and characteristics of the hospitals (tertiary hospital, general hospital, convalescent hospital, or others).

Data analyses

The patients were divided into three groups according to the initial NIHSS score (mild, ≤5; moderate, >5 and ≤13; and severe, >13), and we compared the number of hospitals that admitted patients and the LOS between the groups [7]. We used the Mann–Whitney U test for age and sex, and the Kruskal–Wallis test and Bonferroni's method for severity of the stroke, to examine the differences among or between groups. A multiple regression analysis was used to determine variables that had significant effects on the LOS and the number of hospitals. Because the distribution of the LOS was skewed to the right, the results of the analysis are described as the median and 25th and 75th percentile values.

RESULTS

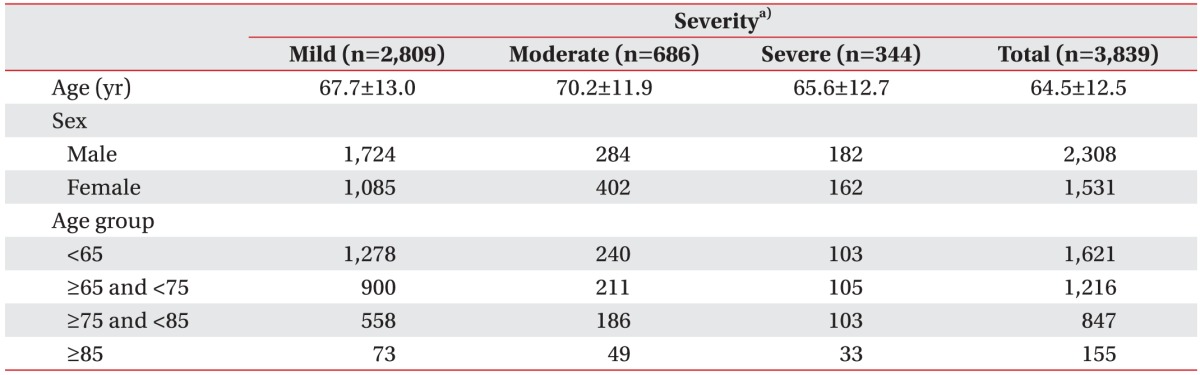

Demographic data

The demographic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1. Of the 3,839 patients (1,724 males and 1,085 females), 2,809 were included in the mild group, 686 in the moderate group, and 344 in the severe group. The patients were classified into four groups according to age (>65; ≥65 and <75; ≥75 and <85; ≥85); mean age was 65.6±12.7 years [8].

Table 1. Demographics of the patients.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number.

a)According to the initial National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score (mild, ≤5; moderate, >5 and ≤13; severe, >13).

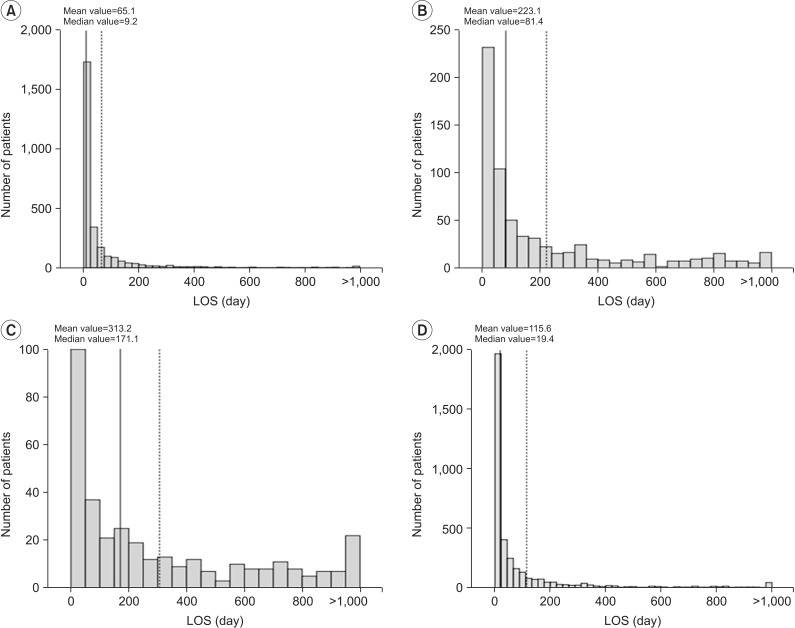

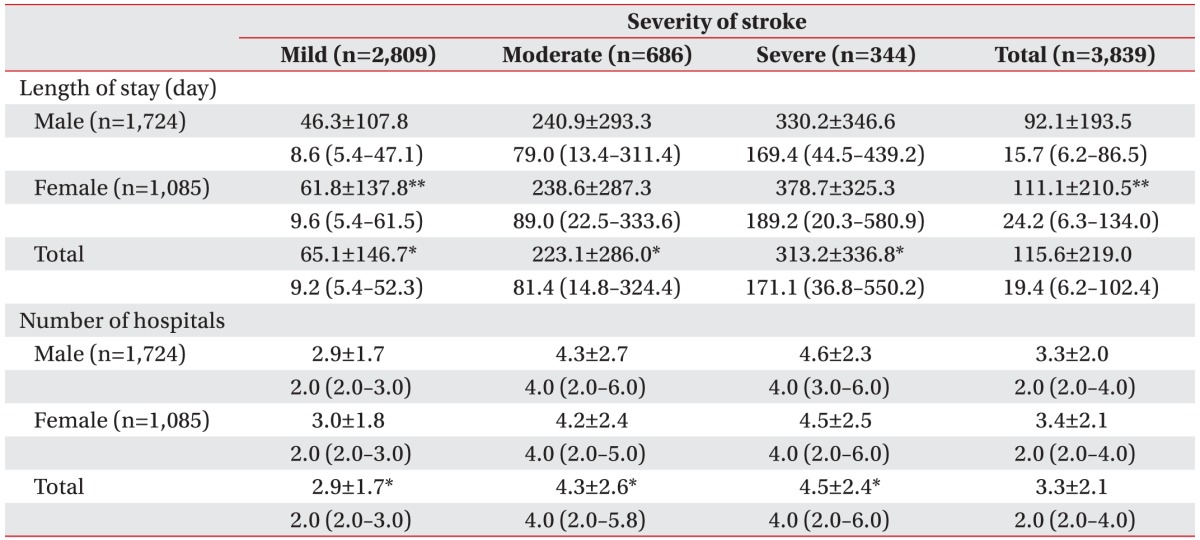

LOS according to the severity of stroke

The mean LOS was 115.6±219.0 days (median, 19.4 days) and the mean number of hospitals that admitted patients after stroke was 3.3±2.1 (median, 2.0). As the severity of the stroke increased the LOS and the number of hospitals also increased (Fig. 2). In the mild group, the mean LOS was 65.1±146.7 days (median, 9.2 days) and the mean number of hospitals was 2.9±1.7 (median, 2.0). In the moderate group, the mean LOS was 223.1±286.0 days (median, 81.4 days) and the mean number of hospitals was 4.3±2.6 (median, 4.0). In the severe group, the mean LOS was 313.2±336.8 days (median, 171.1 days) and the mean number of hospitals was 4.5±2.4 (median, 4.0) (Table 2).

Fig. 2. Length of hospital stay (LOS) according to the severity of stroke. The number of patients and length of hospital stay according to the stroke severity. (A) mild group, (B) moderate group, (C) severe group, and (D) total group. The dashed and solid line shows the average and median value LOS, respectively.

Table 2. Length of hospital stay according to severity of stroke.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range 25th–75th percentile).

*p<0.01, **p<0.05.

LOS according to sex

The mean LOS was longer in women than men (Table 2). However, only the women in the mild group, rather than those in the moderate and severe groups, had a longer LOS compared with that in the men in the corresponding group. There was no significant difference between male group and female group in every age group.

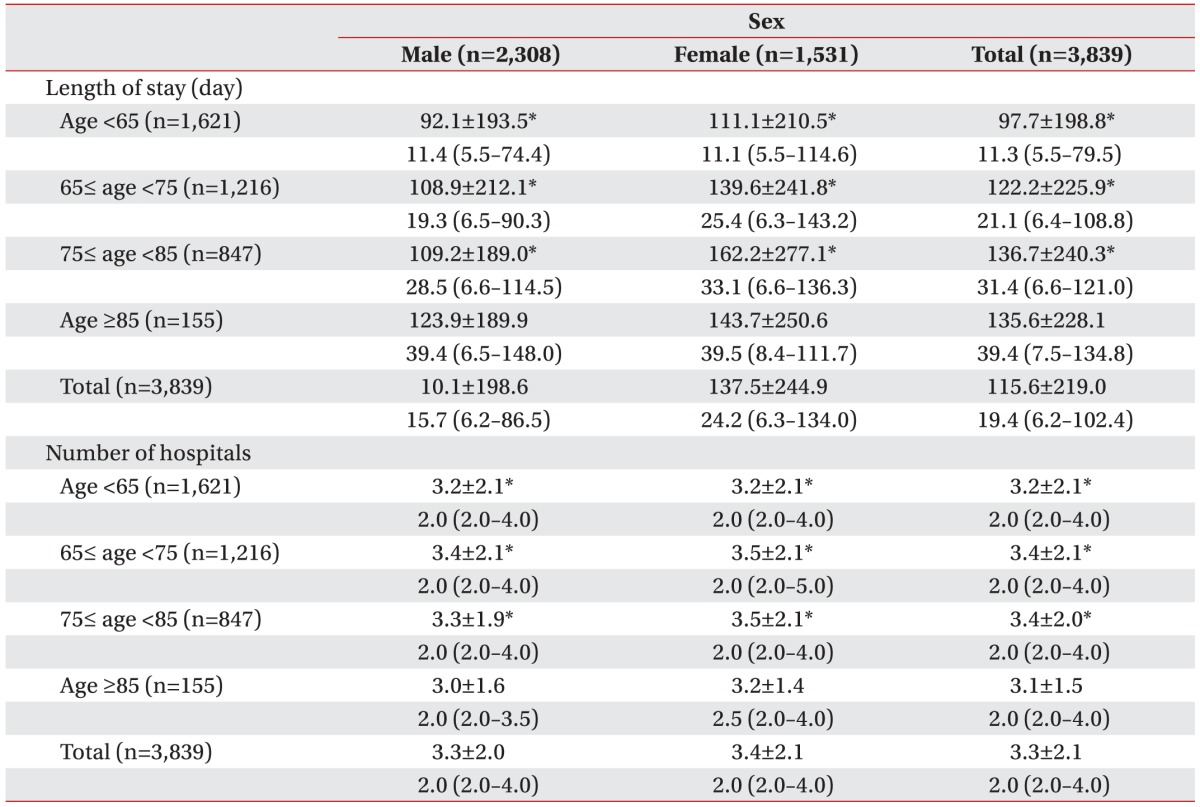

LOS according to age

In total, male, and female groups, the mean LOS was shorter and the mean number of hospitals was smaller in those <65 years of age compared to those between 65 and 75 years of age, and those between 75 and 85 years of age (Table 3).

Table 3. Length of hospital stay according to age and sex.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range 25th–75th percentile).

*p<0.01.

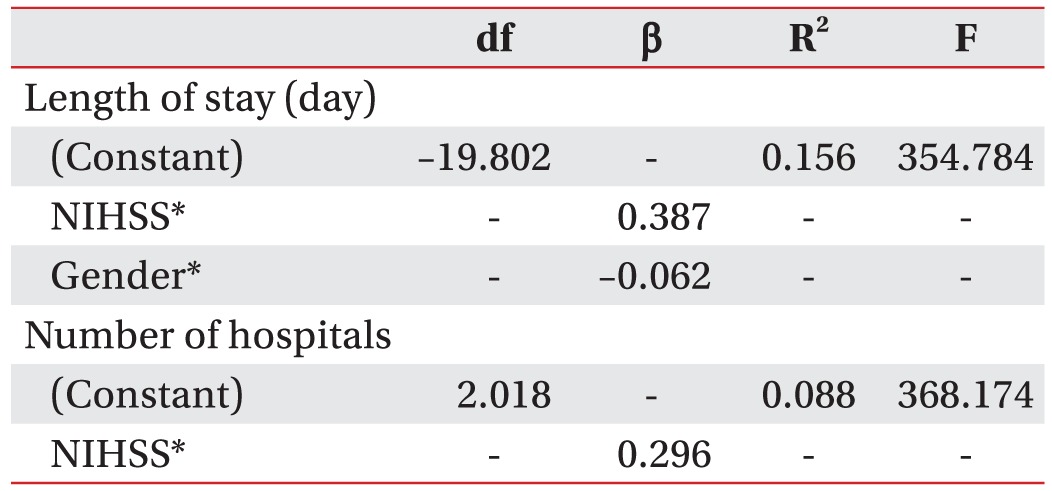

Regression analysis

The results of stepwise multiple regression analysis for LOS and number of hospitals after acute stroke are summarized in Table 4. We used the backward elimination method with three independent variables (NIHSS, age, and sex), and the highest explained variance for LOS after acute stroke was shown in the model when NIHSS and sex were included (R2=0.156). The most significantly correlated factors of the model were shown to be NIHSS (β=0.387, p<0.001) and sex (β=−0.062, p<0.001). NIHSS was the only significant factor for number of hospitals after acute stroke (R2=0.088, β=0.296, p<0.001).

Table 4. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis of length of stay after stroke.

NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

*p<.001.

DISCUSSION

The mean LOS was 115.6±219.0 days (median, 19.4 days) and the mean number of hospitals that admitted patients after stroke was 3.3±2.1 (median, 2.0). As the severity of the stroke increased, LOS and the number of hospitals also increased. The mean LOS was longer and the mean number of hospitals were larger for older patients compared to younger patients.

The distribution of the mean LOS was positively skewed, similar to the results observed in previous studies [5,9,10,11]. The LOS in this study was shorter than that of a previous Korean study, in which the LOS was 191.5 days after stroke [3]. In that study, the researchers collected data of stroke survivors who were listed in the Korean disability registration system. Therefore, the previously surveyed population might have included more severely affected stroke survivors compared with those included in this study. Another previous study in Korea reported 83.6 days as the LOS, but only patients admitted to a tertiary hospital were included [1]. The mean LOS of stroke patients in this study is much longer than that observed in Japan (74.7 days) [12]. Prolonged LOS in Korea may be attributable to socio-economic factors, such as the high level of burden of care owing to the lack of social infrastructure and services, and low medical fees in the national medical insurance system [3]. Studies have reported LOS after stroke in Denmark (13.0 days), Singapore (30.8 days), England (74.9 days in males; 74.7 days in females), Taiwan (11.0 days), the Netherlands (28.0 days), and Sweden (29.0 days) [4,5,10,11,13,14]. However, LOS was analyzed only in tertiary hospitals in these studies. Two studies in the United States (16.5 days) and Japan (74.7 days) reported the LOS only in rehabilitation facilities after discharge from tertiary hospitals, rather than the total LOS from emergency room to home discharge [12,15]. Therefore, it is difficult to directly compare the results of those reports with the results of this study.

LOS was much longer in women than in men, in contrast to the findings of previous foreign studies [5,9,10,14]. In Korea especially, there is a socially accepted idea of family-centered caregiving owing to filial piety and familism, and the burden of caring for stroke patients generally falls on the female caregivers [16]. Therefore, in Korea, male stroke patients might have a better opportunity to secure the support of their caregivers (i.e., spouses) compared with female stroke patients. In this study, age significantly influenced the median LOS, and this result did not correspond with the results of previous studies [4,5,9,10,17]. However, the prior studies classified subjects into two age groups, at or above 75 years vs. less than 75 years [5,10] or at or above 65 years vs less than 65 years [9]. These binary classification of age groups and the difference in criteria for younger vs. older age group could at least partially explain the difference of the results of this study compared to previous reports.

There are several limitations of this study. First, although social support on discharge as well as economic status are significant predictors of increased LOS [1,3,18,19], we could not investigate these variables because only medical information was available in the MOSAIC database. Second, the effect of rehabilitation was not analyzed owing to the lack of data. Inpatient rehabilitation services are a well-known determining factor for cost and LOS after stroke, and stroke survivors who receive rehabilitation might have shorter LOS than those who do not [20,21,22]. Third, the type of stroke was limited to ischemic lesions. Of the 3,839 patients, 3,340 were included in the ischemic group (87.0%), 47 in the ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation group (1.2%), and 454 in the transient ischemic attack group (11.8%). The influence of the type of stroke is still controversial. While one study reported there was no significant difference in the LOS between the hemorrhagic and ischemic groups, another reported that the median LOS was longer for hemorrhagic patients [9,10].

In conclusion, there was an apparent difference in the LOS and the number of hospitals that admitted patients after stroke according to the stroke severity based on the NIHSS. This result could supply evidence for suggesting the appropriate LOS after stroke in the Korean medical system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a 2012 grant from the Korean Academy of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Rhie KS, Rah UW, Lee IY, Yim SY, Kim KM, Moon DJ, et al. The discharge destination of rehabilitation inpatients in a tertiary hospital. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2005;29:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang EK, Kim WS, Jeong SH, Shin HI, Han TR. Desire for rehabilitation services of stroke patients admitted in post-acute rehabilitation facilities. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2007;31:404–409. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung SH, Lee KM, Park SW, Chun MH, Jung HY, Kim IS, et al. Inpatient course and length of hospital stay in patients with brain disorders in South Korea: a population-based registry study. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36:609–617. doi: 10.5535/arm.2012.36.5.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelros P. Prediction of length of stay for stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:15–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang KC, Tseng MC, Weng HH, Lin YH, Liou CW, Tan TY. Prediction of length of stay of first-ever ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:2670–2674. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000034396.68980.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Acute stroke care and rehabilitation: an analysis of the direct cost and its clinical and social determinants. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 1997;28:1138–1141. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.6.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlegel D, Kolb SJ, Luciano JM, Tovar JM, Cucchiara BL, Liebeskind DS, et al. Utility of the NIH Stroke Scale as a predictor of hospital disposition. Stroke. 2003;34:134–137. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000048217.44714.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zizza CA, Ellison KJ, Wernette CM. Total water intakes of community-living middle-old and oldest-old adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:481–486. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxena SK, Koh GC, Ng TP, Fong NP, Yong D. Determinants of length of stay during post-stroke rehabilitation in community hospitals. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan WS, Heng BH, Chua KS, Chan KF. Factors predicting inpatient rehabilitation length of stay of acute stroke patients in Singapore. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svendsen ML, Ehlers LH, Andersen G, Johnsen SP. Quality of care and length of hospital stay among patients with stroke. Med Care. 2009;47:575–582. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195f852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyai I, Sonoda S, Nagai S, Takayama Y, Inoue Y, Kakehi A, et al. Results of new policies for inpatient rehabilitation coverage in Japan. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:540–547. doi: 10.1177/1545968311402696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Straten A, van der Meulen JH, van den Bos GA, Limburg M. Length of hospital stay and discharge delays in stroke patients. Stroke. 1997;28:137–140. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakim EA, Bakheit AM. A study of the factors which influence the length of hospital stay of stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12:151–156. doi: 10.1191/026921598676265330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granger CV, Reistetter TA, Graham JE, Deutsch A, Markello SJ, Niewczyk P, et al. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation: report of patients with hip fracture discharged from comprehensive medical programs in 2000-2007. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:177–189. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31820b18d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JS, Lee EH. Cultural and noncultural predictors of health outcomes in Korean daughter and daughter-in-law caregivers. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20:111–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feigenson JS, McDowell FH, Meese P, McCarthy ML, Greenberg SD. Factors influencing outcome and length of stay in a stroke rehabilitation unit. Part 1. Analysis of 248 unscreened patients: medical and functional prognostic indicators. Stroke. 1977;8:651–656. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monane M, Kanter DS, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Variability in length of hospitalization for stroke. The role of managed care in an elderly population. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:875–880. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550090073013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena SK, Ng TP, Yong D, Fong NP, Gerald K. Total direct cost, length of hospital stay, institutional discharges and their determinants from rehabilitation settings in stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner-Stokes L, Sutch S, Dredge R. Healthcare tariffs for specialist inpatient neurorehabilitation services: rationale and development of a UK casemix and costing methodology. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:264–279. doi: 10.1177/0269215511417467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner-Stokes L, Scott H, Williams H, Siegert R. The Rehabilitation Complexity Scale: extended version. Detection of patients with highly complex needs. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:715–720. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.615880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner-Stokes L, Sutch S, Dredge R, Eagar K. International casemix and funding models: lessons for rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:195–208. doi: 10.1177/0269215511417468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]