Abstract

The sclerotic ring consists of several bones that form in the sclera of many reptiles. This element has not been well studied in squamates, a diverse order of reptiles with a rich fossil record but debated phylogeny. Squamates inhabit many environments, display a range of behaviours, and have evolved several different body plans. Most importantly, many species have secondarily lost their sclerotic rings. This research investigates the presence of sclerotic rings in squamates and traces the lineage of these bones across evolutionary time. We compiled a database on the presence/absence of the sclerotic ring in extinct and extant squamates and investigated the evolutionary history of the sclerotic ring and how its presence/absence and morphology is correlated with environment and behaviour within this clade. Of the 400 extant species examined (59 families, 214 genera), 69% have a sclerotic ring. Those species that do not are within Serpentes, Amphisbaenia, and Dibamidae. We find that three independent losses of the sclerotic ring in squamates are supported when considering both evolutionary and developmental evidence. We also show that squamate species that lack, or have a reduced, sclerotic ring, are fossorial and headfirst burrowers. Our dataset is the largest squamate dataset with measurements of sclerotic rings, and supports previous findings that size of the ring is related to both environment occupied and behaviour. Specifically, scotopic species tend to have both larger inner and outer sclerotic ring apertures, resulting in a narrower ring of bone than those found in photopic species. Non‐fossorial species also have a larger sclerotic ring than fossorial species. This research expands our knowledge of these fascinating bones; with further phylogenetic analyses scleral ossicles could become an extremely useful character trait for inferring the behaviour of fossil squamates.

Keywords: morphology, scleral ossicles, skeleton

Introduction

The vertebrate ocular skeleton is an important part of the craniofacial skeleton that is present in many lineages (Walls, 1942; Franz‐Odendaal & Hall, 2006). It is composed of a cartilaginous component, called scleral cartilage and/or a bony component, called the scleral ossicles, that when present in reptiles forms a sclerotic ring (Walls, 1942). Several lineages have only the cartilaginous component (i.e. chondrichthyans, crocodiles, some basal mammals, and most actinopterygians) whereas others have both scleral cartilage and scleral ossicles (i.e. testudines, avians, most squamates, and many teleosts and dinosaurs) (Walls, 1942; Franz‐Odendaal & Hall, 2006; Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a). In extant reptiles [i.e. Curtis & Miller, 1938 (birds); Underwood, 1970, 1984 (lizards); Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a; (turtles); Hall, 2008a,b, 2009 (birds and lizards)], the scleral cartilage is present as a cup that forms around the posterior portion of the eye, whereas the scleral ossicles are positioned at the corneal‐scleral limbus (the anterior portion of the eye) and form the sclerotic ring (Fig. 1, de Beer, 1937). Walls (1942) suggested that the sclerotic ring is important for accommodation (i.e. visual acuity); however, it may additionally prevent distortion of the posterior portion of the eye when the cornea changes shape to focus light on the retina (Walls, 1942).

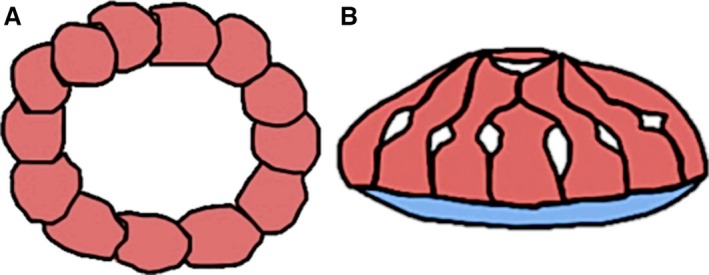

Figure 1.

The ocular skeletal morphology in reptiles. (A) The sclerotic ring (red) showing individual ossicles in the chicken. (B) The ocular skeleton in the European green lizard with the sclerotic ring and the scleral cartilage (blue). Figure modified from Franz‐Odendaal (2011).

Several authors have demonstrated that ocular skeletal morphology is a good indicator of behaviour in many species (e.g. Curtis & Miller, 1938; Caprette et al. 2004; Fernández et al. 2005; Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a; Hall, 2008a,b, 2009; Pilgrim & Franz‐Odendaal, 2009; Schmitz & Motani, 2011a). For example, presence or absence of scleral ossicles in teleost fish appears to correlate with activity level and environment (Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a). Relatively inactive teleosts (e.g. Gasterosteiformes and Lophiiformes), as well as those living in deep‐sea habitats, tend to lack scleral ossicles, whereas more active fish (e.g. Salmoniformes and Cypriniformes) have one or two scleral ossicles per eye (Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a). In birds, similar patterns exist, for example, diving birds have more robust (e.g. heavier and more rigid) rings compared with other species, and both diving birds and rapid fliers have a steeper sclerotic ring slope than other species as a consequence of their tubular eye shape (Curtis & Miller, 1938). More significant for this study, it has been shown that soft tissue morphology in birds and squamates is correlated with the environment in which the animal lives (e.g. Hall, 2008a,b, 2009). Hall (2008a,b, 2009) showed that the corneal diameter could be used to distinguish between photopic (smaller apertures) and scotopic (larger apertures) birds and squamates. For example, scotopic lizards active in low‐light conditions, such as nocturnal lizards, have larger corneal diameters than squamates in photopic habitats (Hall, 2008a). Furthermore, Schmitz & Motani (2011a) showed using phylogenetic discriminate analysis that the sclerotic ring aperture is a reliable method of inferring diel activity in extinct archosaurs (e.g. dinosaurs and pterosaurs).

In this study, we investigate and measure the hard tissue of the eye, specifically the sclerotic ring, in order to deterrmine whether it is a good measure of inferring diel activity within extant squamates. While the studies of Hall (2008a,b, 2009) measured the corneal diameters in extant squamates and avians, Schmitz & Motani (2011a) measured fossil archosaurs. Thus neither provides a clear representation of the distribution of sclerotic rings among extant and fossil squamates. Squamates (i.e. snakes, lizards, and their relatives) are a large clade with over 9000 species (Pyron et al. 2013). This clade has evolved several different body plans, inhabits many environments (e.g. fossorial, terrestrial, arboreal) and displays a range of behaviours. In addition, some species do not have a sclerotic ring. Here, we compiled a database with over 400 extant and 19 fossil squamate species documenting the presence/absence of the sclerotic ring. In total, our analysis increases the existing dataset by at least 178 species. Secondly, we investigated the evolutionary history of the sclerotic ring by plotting our data on both morphological and molecular phylogenies for this clade. Finally, to assess how sclerotic ring presence/absence and morphology are correlated with environment and behaviour within squamates, we measured 100 extant specimens from seven different families.

Methods

A database of presence and absence of the sclerotic ring in extinct and extant species was compiled by surveying available literature, online databases, and museum collections at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of Natural History (UK). To determine the presence of the sclerotic rings in a taxon, we only assessed specimens that had complete eyes (i.e. they were not removed during the preparation process). In total, data was obtained on 400 extant species, representing 214 genera and 59 families (Table 1). Although these data do not represent all of Squamata, which has over 9000 species, we have representatives from every lineage and in many cases have sampled all the known genera in a family.

Table 1.

Summary of all extant families (n = 59) and genera (n = 214) assessed

| Higher taxonomic classification | Family | Genera | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iguania | Agamidae | Acanthocercus, Agama, Calotes, Draco, Leiolepis, Moloch, Physignathus, Pogona, Uromastyx | Present (1) |

| Chamaeleonidae | Brookesia, Chamaeleo, Rhampholeon | Present (1) | |

| Corytophanidae | Basiliscus, Corytophanes | Present (1) | |

| Crotaphytidae | Crotaphytus, Gambelia | Present (1) | |

| Dactyloidea | Anolis | Present (1) | |

| Hoplocercidae | Enyalioidea, Hoplocercus, Morunasaurus | Present (1) | |

| Iguanidae | Anisolepis, Brachylophus, Cophosaurus, Cyclura, Dipsosaurus, Sauromalus | Present (1) | |

| Leicephalidae | Leiocephalus | Present (1) | |

| Leiosauridae | Leiosaurus, Pristidactylus, Urostrophus | Present (1) | |

| Liolaemidae | Liolaemus, Phymaturus | Present (1) | |

| Opluridae | Chalarodon, Oplurus | Present (1) | |

| Phrynsomatidae | Holbrookia, Callisaurus, Petrosaurus, Phrynosoma, Sceloporus, Uma, Uta | Present (1) | |

| Polychrotidae | Polychrus | Present (1) | |

| Tropiduridae | Plica, Stenocercus, Tropidurus, Uranoscodon | Present (1) | |

| Gekkota | Diplodactylidae | Nephrurus | Present (1) |

| Eublepharidae | Hemitheconyx | Present (1) | |

| Gekkonidae | Aristelliger, Cosymbotus, Gehyra, Gekko, Hemidactylus, Heteronota, Hoplodactylus, Lepidodactylus, Lucasius, Naultinus, Oedura, Pachydactylus, Perochirus, Peropus, Phelsuma, Phyllurus, Pseudogekko, Rhacodactylus, Rhynchoedura, Saltuarius, Strophurus, Teratoscincus | Present (1) | |

| Pygopodidae | Lialis, Pletholax, Pygopus | Present (1) | |

| Sphaerodactylidae | Gonatodes, Sphaerodactylus | Present (1) | |

| Lacertoidea | Lacertidae | Acanthodactylus, Adolfus, Gallotia, Holaspis, Lacerta, Latastia, Meroles, Mesalina, Ophisops, Philochortus, Podarcis, Psammodromus, Pseuderemias, Takydromus, Zootoca | Present (1) |

| Teiidae | Aspidoscelis, Ameiva, Callipistes, Cnemidophorus, Kentropyx, Neusticurcus, Teius, Tupinambis | Present (1) | |

| Gymnophthalmidae | Alexandrasaurus, Bachia, Colobosaura, Gymnophthalmus, Pholidobolus | Present (1) | |

| Xantusiidae | Cricosaura, Lepidophyma, Xantusia | Present (1) | |

| Scincoidea | Acontidae | n/a | Present (1) |

| Cordylidae | Chamaesaura, Cordylus, Platysaurus | Present (1) | |

| Feylinidae | n/a | Present (1) | |

| Gerrhosauridae | Angolosaurus, Cordylosaurus, Gerrhosaurus, Tracheloptychus, Zonosaurus | Present (1) | |

| Scelotidae | n/a | Present (1) | |

| Scincidae | Ablepharus, Acontias, Amphiglossus, Brachymeles, Carlia, Chalcides, Cordylosaurus, Corucia, Cryptoblepharus, Emoia, Egernia, Eugongylus, Eumeces, Feylinia, Lamprolepis, Lampropholis, Lepininia, Mabuya, Plestiodon, Ristella, Scincella, Scincus, Sphenomorphus, Tiliqua, Trachylepis | Present (1) | |

| Anguimorpha | Anguidae | Abronia, Anguis, Barisia, Celestus, Diploglossus, Dopasia, Elgaria, Gerrhonotus, Ophiodes, Ophisaurus, Pseudopus | Present (1) |

| Anneillidae | Anniella | Present (1) | |

| Helodermatidae | Heloderma | Present (1) | |

| Lanthanotidae | Lanthanotus | Present (1) | |

| Shinisauridae | Shinisaurus | Present (1) | |

| Varanidae | Varanus | Present (1) | |

| Xenosauridae | Xenosaurus | Present (1) | |

| Amphisbaenia + Dibamidae | Amphisbaenidae | Amphisbaena, Ancylocranium, Anops, Aulura, Baikia, Chirindia, Cynisca, Dalophia, Geocalamus, Leposternon, Loveridgea, Mesobaena, Monopeltis, Zygaspis | Present (1) |

| Bipedidae | Bipes | Present (1) | |

| Blanidae | Blanus | Present (1) | |

| Cadeidae | Cadea | Present (1) | |

| Dibamidae | Anelytropsis, Dibamus | Absent (0) | |

| Rhineuridae | Rhineura | Absent (0) | |

| Trogonophidae | Agamodon, Diplometopon, Pachycalamus, Trogoniphis | Present (1) | |

| Serpentes | Aniliidea | Anilius | Absent (0) |

| Anomalepididae | Liotyphlops, Typhlophis | Absent (0) | |

| Anomochilidae | Anomoschilus | Absent (0) | |

| Boidae | Boa, Eryx, Lichanura | Absent (0) | |

| Bolyeriidae | Casarea | Absent (0) | |

| Colubridae | Amphiesma, Coluber, Diadophis, Heterodon, Homalopsis, Lycophidion, Natrix, Sonora, Thamnophis, Trimorphodon, Xenochrophis | Absent (0) | |

| Cylindeophiidae | Cylindrophis | Absent (0) | |

| Elapidae | Laticauda, Micrurus, Naja | Absent (0) | |

| Leptyphlopidae | Leptotyphlops | Absent (0) | |

| Loxocemidae | Loxocemus | Absent (0) | |

| Pythonidae | Python | Absent (0) | |

| Tropidophiidae | Tropidophis, Ungaliophis | Absent (0) | |

| Typhlopidae | Typhlops | Absent (0) | |

| Uropeltidae | Uropeltis | Absent (0) | |

| Xenopeltidae | Xenopeltis | Absent (0) | |

| Viperidae | Agkistrodon, Bothropoides, Bothrops, Calabaria, Causus, Lachesis | Absent (0) |

Fossil specimens are often fragmentary and/or poorly preserved (Conrad, 2008), making it difficult to obtain accurate and complete morphological information. Therefore, we scanned the literature to identify well‐preserved specimens with reasonably complete skeletons or skulls. In total, 167 fossil specimens that could potentially be useful were identified; however, only 19 fossil species were complete enough to assess presence/absence confidently (Supporting Information Table S1). We therefore only include these 19 species in our analyses.

To map the gains and losses of sclerotic rings on the squamate phylogeny, the literature was surveyed for well‐cited and supported phylogenies. We used the most recent morphological phylogenetic analysis, conducted by Gauthier et al. (2012), who assessed 192 species for 610 morphological characters. We also used the most recent molecular phylogenetic study, conducted by Pyron et al. (2013), who assessed 4161 species using 12 genes (seven nuclear loci and five mitochondrial genes). To map the presence/absence of the sclerotic ring, we mapped this trait on the maximum parsimony Adams consensus from Gauthier et al. (2012) and the maximum likelihood from Pyron et al. (2013).

To assess whether the loss of the sclerotic ring is correlated with environment and/or behaviour in squamates, we (i) conducted a literature review of diel activity and fossorial habitat for the families examined here (Supporting Information Table S2), (ii) assessed the literature for lineages with reduced limbs, as species that lack a sclerotic ring and/or have a fossorial lifestyle belong to lineages that are known to also have reduced limbs (e.g. Kearney, 2003; Wiens et al. 2010), and (iii) measured sclerotic ring diameters, as these measurements have been used to assess diel activity in previous studies either in conjunction with soft tissue analyses (e.g. Hall, 2008a, 2009) or in extinct archosaurs (Schmitz & Motani, 2011a). Specifically, we measured the inner diameter (aperture) and the outer maximum diameter of the sclerotic ring. The inner diameter has been shown to be representative of the corneal diameter (e.g. Hall, 2008a,b). For most specimens, these measurements were taken using a dissecting microscope fitted with an ocular micrometer and rounded to the nearest micrometer. Some larger specimens required the use of digital calipers for measurements. In total, we measured 100 dry and alcohol‐preserved specimens from the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USA) and the Museum of Natural History (UK) (Supporting Information Table S3). These specimens represent seven families and 31 genera in Gekkota and Scincomorpha. As the data were not normally distributed, Mann–Whitney tests (to compare between families) and Kruskal–Wallis tests (to compare species with different behaviours/habitats) were used with a 95% confidence interval. We performed analyses between species that were scotopic (either active during low‐light conditions or fossorial species that live in low‐light conditions) vs. photopic (active during light conditions, e.g. during the day), and fossorial vs. non‐fossorial, for both the inner and outer sclerotic ring diameters. Finally, we plotted the log10 transformation of the inner and outer measurements and performed a Spearman correlation between the two measurements using Microsoft excel and minitab 16.

Results

Overview of the presence and absence of the sclerotic ring in squamates

The presence/absence data collected was plotted on a morphological phylogeny (Fig. 2) and a molecular phylogeny (Fig. 3). According to morphological data, Squamata has five extant lineages: Iguania, Gekkota, Scincomorpha, Anguimorpha (into which the limbless Amphisbaenia and Dibamidae are grouped), and Serpentes. Of these lineages, only Anguimorpha and Serpentes have families that lack a sclerotic ring (Table 1). All families (n = 29) and species (n = 285) examined in Iguania, Gekkota, and Scincomorpha have a sclerotic ring, whereas all the Serpentes families (n = 16) and species examined (n = 41) lack a sclerotic ring (Table 1). Within Anguimorpha families (n = 14), 12 families (37 species) have a sclerotic ring, whereas in Dibamidae (six species from two genera) and Rhineuridae (one species from one genera) all members lack a sclerotic ring (Table 1). The sclerotic ring is therefore present in the majority of squamate families (69%, 41 of 59 sampled) and all of the species that lack a sclerotic ring are found within Serpentes, amphisbaenians, and dibamids (Table 1). Note that these groups are all within Gauthier et al.'s (2012) ‘Krypteia’, although ‘Krypteia’ is not well‐supported by morphological or molecular data (e.g. Conrad, 2008; Gauthier et al. 2012; Pyron et al. 2013). These researchers and others are of the opinion that ‘Krypteia’ is frequently recovered in morphological phylogenies due to their shared absence of many identifying skeletal characters (e.g. Lee, 1998; Kearney, 2003; Conrad, 2008; Wiens et al. 2010; Gauthier et al. 2012; Pyron et al. 2013). ‘Krypteia’ is not recovered using molecular phylogenetics and is statistically weakly supported in morphological phylogenies.

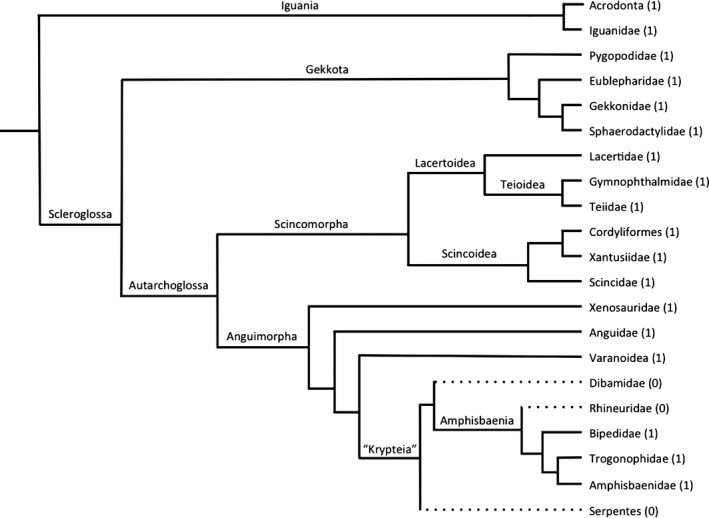

Figure 2.

Family level morphology‐based phylogeny of extant squamates modified from the maximum parsimony Adams consensus from Gauthier et al. (2012). Solid lines (1) indicate lineages where the sclerotic ring is present and broken lines (0) indicate lineages where the sclerotic ring is absent.

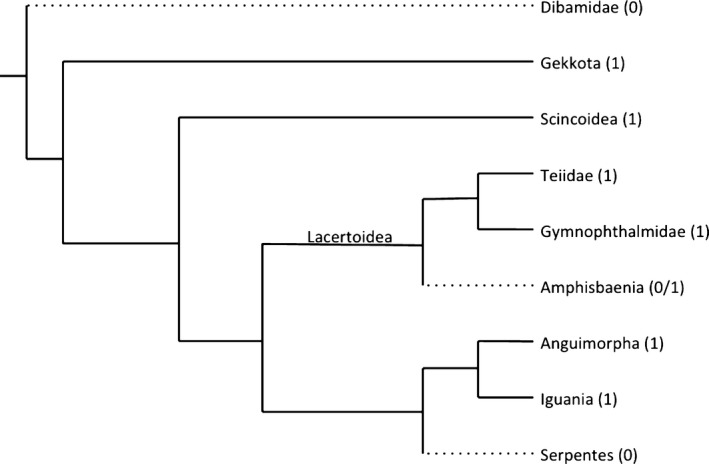

Figure 3.

Molecular phylogeny modified from the maximum likelihood phylogeny from Pyron et al. (2013). Solid lines (1) indicate lineages where the sclerotic ring is present and broken lines (0) indicate lineages where the sclerotic ring is absent in some species.

To better understand sclerotic ring evolution, we also assessed presence/absence of the sclerotic ring in fossil squamates (n = 19 species) in which the sclerotic ring was either reported or the specimen was sufficiently well‐preserved and articulated to make an accurate assessment (Table S1). About 84% of the fossil specimens that were complete enough to assess (i.e. 16 of 19), have a sclerotic ring or a remnant thereof (Supporting Information Fig. S1 shows the phylogenetic distribution of these fossils). Sclerotic rings are present in fossil Iguanidae (n = 1), Mosasauria (an extinct group of marine reptiles, n = 6), Gekkota (n = 1), Lacertoidea (n = 1), and Anguimorpha (n = 4). Three species (Jucaraseps grandipes, Scandensia cievensis, and Yabeninosaurus tenuis) have a remnant of a sclerotic ring. These three taxa are considered stem scleroglossans (see Evans & Barbadillo, 1998; Evans et al. 2005; Evans & Wang, 2010; Bolet & Evans, 2012), a group that is recovered using morphological data (e.g. Conrad, 2008; Gauthier et al. 2012); the other is Iguania. Interestingly, when using molecular data Scleroglossa is not recovered (e.g. Pyron et al. 2013). The remaining three species examined, lack a sclerotic ring; two of those species are in Amphisbaenia (in Rhineuridae) and one is a fossil snake. Despite the relatively small numbers of fossil specimens examined, these results are in agreement with our extant data and indicate that the loss of the sclerotic ring is a derived trait.

Environment, behaviour, and limb morphology of extant squamates

To assess whether the loss of the sclerotic ring is correlated with environment and/or behaviour in squamates, we conducted a literature review into the diel activity, fossorial habitat, and limbless morphology (Table S2). In the lineages that have lost the sclerotic ring (namely Dibamidae, Rhineuridae, and Serpentes), only the diel activity of Serpentes is certain. Both scotopic and photopic species of snakes exist, and the diel activity of dibamids and rhineurids is currently unresolved. The ancestral state for diel activity in squamates is photopic, with scotopic activity evolving in several lineages (Hall, 2008a).

A fossorial (burrowing) lifestyle has also been correlated with a simplification of the body plan, including the loss of limbs (e.g. Gans, 1978; Kearney, 2003; Wiens et al. 2006). In our dataset, nine of 21 families (43%) have a reported fossorial lifestyle, and 11 of 21 (52%) are limbless (Table S2). The fossorial species in our dataset are those species belonging to ‘Krypteia’ (shorthand for an unresolved group that consists of Dibamidae, Amphisbaenia, and Serpentes; Gauthier et al. 2012), Pygopodidae (in Gekkota) and some species in Gymnophthalmidae and Scincidae (both in Scincomorpha). The limbless species are also those found in ‘Krypteia’, Pygopodidae, Gymnophthalmidae, Anguidae, as well as some Cordyliformes. These data indicate that both a fossorial lifestyle and limb reduction have evolved several times in Squamata and this has occurred in Gekkota, Scincomorpha, Anguimorpha, and Serpentes; all groups within Scleroglossa. These traits may therefore have co‐evolved with sclerotic ring reduction or complete absence within Anguimorpha and Serpentes but curiously not within Gekkota or Scincomorpha. It follows that while absent or reduced sclerotic rings are always correlated with reduced limbs and a fossorial lifestyle, the opposite is not always the case.

Sclerotic ring measurements

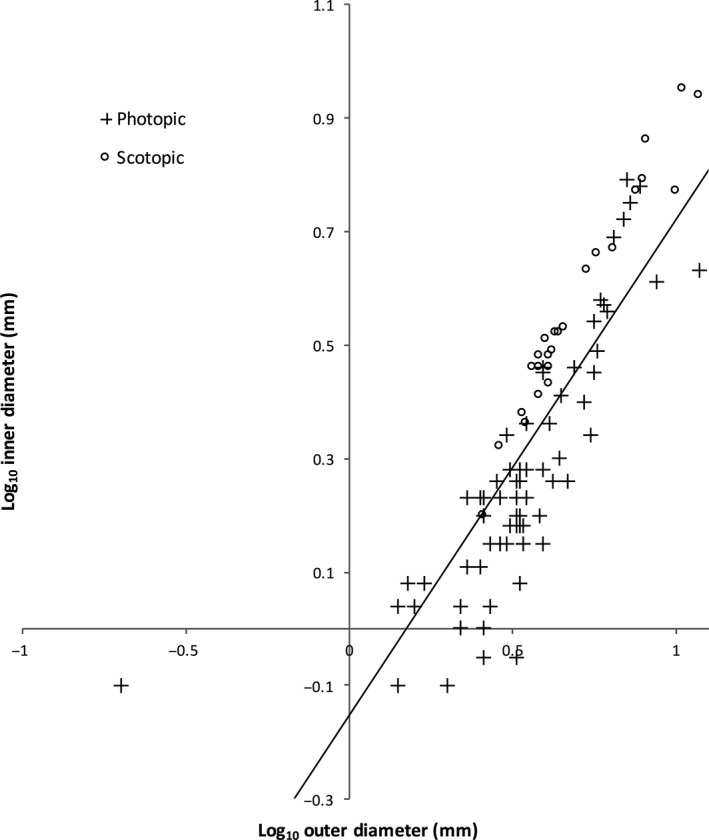

To better understand the morphological differences between families and genera with different ecological niches, statistical analyses were performed on measurements of the maximum inner and outer diameters of the sclerotic ring. The average maximum inner diameter was 2.6 ± 1.7 mm and the maximum outer diameter was 4.3 ± 2.4 mm (average ± SD). First, we plotted the inner and outer diameters against each other using the log10‐transformed values of our measurements (Fig. 4). Then, a correlation test was performed that determined that the inner and outer diameter measurements are highly related (r 2 = 0.712, P < 0.001), indicating that there is a positive relationship between the two diameters (i.e. larger inner diameters also mean larger outer diameters; Fig. 4). This indicates that larger sclerotic rings tend to be narrow, whereas smaller sclerotic rings are comparatively wider. Additionally, the inner and outer diameters were significantly different between families (P < 0.001), and also between known scotopic and known photopic species (P < 0.001), and between fossorial and non‐fossorial species (P < 0.001), even when taking into account body size. These measurements are given in Table 2. Under conservative testing procedures using a Bonferroni correction (α = 0.003), all tests were still statistically significant. This suggests that body size is not a factor in how large or small a sclerotic ring is, but rather the environment in which the animal lives correlates with ring size. Interestingly, photopic species tend to have smaller sclerotic rings (both aperture, or inner diameter, and outer diameter of the ring) than scotopic species (Fig. 4), and fossorial species have smaller sclerotic rings than non‐fossorial species. Therefore, we can conclude that photopic or fossorial species have smaller eyes (and smaller sclerotic rings) than scotopic or non‐fossorial species.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between the outer diameter and the inner diameter of the sclerotic line. Log10 values were taken of all the measurements and plotted. The line of best fit for photopic (n = 75) and scotopic (n = 25) specimens is shown. A correlation test indicated a positive relationship between the two measurements (r 2 = 0.712).

Table 2.

Average inner and outer sclerotic ring measurements (mm) with standard deviations for scoptic, photopic, fossorial, and non‐fossorial specimens

| Average inner diameter (mm) | Average outer diameter (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Scotopic | 4.1 ± 2.0 | 5.5 ± 2.6 |

| Photopic | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 1.6 |

| Fossorial | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| Non‐fossorial | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 1.9 |

Discussion

To determine how many losses of the sclerotic ring occurred over the course of squamate evolution, we have considered the most recent and comprehensive morphological and molecular phylogenies, as well as developmental and evolutionary evidence. We have also considered the shared derived traits of the species that lack a sclerotic ring, as well as behaviour and ecological niches that may have contributed to the loss of the sclerotic ring in these species. We start with an evo‐devo perspective of squamate scleral ossicles and conclude with presenting our data on the scotopic past and environmental (ecological) data.

An evolutionary perspective: morphological vs. molecular

The morphology‐based phylogeny from Gauthier et al. (2012) considers both extant and fossil species. This phylogeny supports the traditional division between Scleroglossa and Iguania, and Amphisbaenia, Dibamidae, and Serpentes (Fig. 2). Using this phylogeny, the most parsimonious scenario supports one loss (at the base of ‘Krypteia’, which encompasses Serpentes, Amphisbaenia, and Dibamidae) and one secondary gain at the base of the clade that encompasses Trogonophidae, Bipedidae, and Amphisbaenidae (Fig. 2).

The molecular‐based phylogeny by Pyron et al. (2013) considers only extant squamates. In this phylogeny, Dibamidae diverged from the other squamate lineages very early on its evolutionary history (Fig. 3). Amphisbaenia and Serpentes are not closely related; Amphisbaenia is nested within Lacertoidea and Serpentes is the sister group to Iguania and Anguimorpha. Importantly, Gauthier et al.'s (2012) ‘Krypteia’ is not recovered in this molecular phylogeny. Using this molecular phylogeny, the most parsimonious scenario is three individual losses of the sclerotic ring, one in Dibamidae, one in Serpentes, and one in Amphisbaenia (Fig. 3).

From a phylogenetic perspective, it has been speculated by many researchers (e.g. Lee, 1998; Conrad, 2008; Wiens et al. 2010; Gauthier et al. 2012) that the close relationships recovered between the limbless families that are found using morphological evidence are the result of the shared absence of traits in these groups. It is therefore quite likely that the families in ‘Krypteia’ are not actually closely related; their relationships are also not supported using molecular phylogenetic methods (e.g. Pyron et al. 2013). Therefore, it seems more likely that multiple losses of the sclerotic ring occurred over evolution in this clade (one each in Dibamidae, Serpentes, and Rhineuridae), which is in keeping with the results from the molecular analyses.

Research conducted by Wiens et al. (2006) showed that extant limbless groups differ significantly in their body morphology. For example, members of the family Bipedidae have forelimbs, whereas all other amphisbaenians do not. Wiens et al. (2006) found two morphologies, limb‐reduced species with long tails that are commonly surface dwellers, and limb‐reduced species with short tails that tend to be burrowers. Interestingly, amphisbaenians, dibamids, and snakes all fall into the short‐tailed burrower group (Wiens et al. 2006), along with several species that have a sclerotic ring (e.g. species in Scincidae and Gekkota, see Table 1). We therefore hypothesize that short‐tailed burrowers are more likely to lack or have reduced sclerotic rings; however, further research into the sclerotic ring of short‐tailed burrowers is required.

Independent evolution of limblessness and fossorial lifestyles has occurred at least 25 times in Squamata in every lineage except Iguania (Wiens et al. 2006; Urben et al. 2014). Müller et al. (2011) suggested, based on the fossil specimen Cryptolacerta hassiaca that, in amphisbaenians, skull modification preceded body elongation and limb reduction. This hypothesis differs from that which is commonly accepted for snakes, where limbs were lost before cranial modifications evolved (e.g. Gans, 1978; Greer, 1991; Wiens et al. 2001). Müller et al. (2011) suggests that amphisbaenians and snakes may have independently evolved reduced limbs and skull modifications associated with a fossorial lifestyle, and that their shared ecological characters may be masking different character evolutionary histories. This theory has also been suggested by Lee (1998) and others studying morphological characters (e.g. Conrad, 2008; Wiens et al. 2010; Gauthier et al. 2012). The independent evolution of limblessness and movement into fossorial habitats supports this theory. Furthermore, it has also been suggested that the sclerotic ring has been independently lost several times in placental mammals, snakes, and some teleosts (Edinger, 1929; Walls, 1942; Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a,b). Therefore, based on the evidence presented here and the weakly supported close relationships between dibamids, rhineurids, and snakes, we conclude that multiple losses of the sclerotic ring within Squamata are similarly likely.

A developmental perspective

Developmentally, the only investigations that have been conducted on the mechanisms of ossicle loss or gain have been conducted in the chicken. In this organism, it has been shown that the ossicles are induced by specializations of the epithelium above the sclera (Coulombre et al. 1962). These regions are known as conjunctival papillae and they are induced to form in a complex, sequential order across the eye (Franz‐Odendaal, 2008a,b). This inductive sequence appears conserved among reptilians (Franz‐Odendaal, 2011) and is the mechanism by which all reptilian scleral ossicles are induced (Franz‐Odendaal, 2006, 2008b). Studies have shown that individual scleral ossicle losses can occur via removal of the inducing epithelial tissue either manually or chemically (Coulombre et al. 1962; Franz‐Odendaal, 2008b; Duench & Franz‐Odendaal, 2012). Significantly, complete loss of an entire sclerotic ring has not been achieved experimentally to date. Additionally from the existing developmental data, we know that the only way a sclerotic ring can be acquired in a species is via the development of a series of conjunctival papillae (Murray, 1943; Coulombre et al. 1962; Jourdeuil & Franz‐Odendaal, 2012). Experimentally inducing a single or even multiple conjunctival papillae to form de novo in a species without ossicles has not been achieved. Induction of the ring of papillae would require not only the presence of the correct as yet unknown induction factors, but would also require competency of the epithelium to respond to these factors and the complex system of sequential induction to be in place. This is in contrast to knocking out an ossicle, or potentially an entire sclerotic ring, which would require either the loss of a single factor (as demonstrated experimentally already) or loss of tissue competency. Indeed, several studies have shown that a single mutation can knock out an entire skeletal element in vertebrates (e.g. Neuhauss et al. 1996; Hall, 2014), and others have found that in many cases, loss of gene function drives adaptation (e.g. Cutter & Jovelin, 2015). Thus it appears that sclerotic ring loss could occur more readily in nature (e.g. via genetic mutation over the course of evolution) than gains, which would involve the establishment of a complex inductive system.

A scotopic past?

It was first suggested by Walls (1942) that scotopic vision might be correlated with the loss of the sclerotic ring and it is certainly true that fossorial species inhabit low‐light environments. Walls (1942) observed a correlation between species that live in scotopic environments, and their lack of sclerotic rings (e.g. crocodiles and mammals). In reptiles, sclerotic rings likely play a role in visual accommodation by preventing distortion of the retina (Edinger, 1929; Walls, 1942); therefore, lineages that have lost the sclerotic ring must, at some point in their past, have gone through a stage where accommodation was not essential. A fossorial lifestyle meets these requirements, as the laterally positioned eyes found in squamates are not particularly useful for an underground lifestyle as they would be in surface‐dwelling species (Walls, 1942). Similarly, Synapsida, a lineage that includes mammal‐like reptiles and mammals, have sclerotic rings, whereas extinct and extant placental mammals do not (Rowe, 1988; Castanhinha et al. 2013). Furthermore, the earliest known mammal, Juramaia, is thought to have been nocturnal (see the review from Gerkema et al. 2013). Therefore, it is likely that as dibamids, amphisbaenians, and possibly snakes moved in to occupy low‐light environments, there was selection pressure to conserve vision and the eye, and therefore the sclerotic ring was progressively lost. Dibamids and rhineurids are examples of lineages that are fossorial and have reduced visual acuity, and perhaps low‐light environments contributed to the loss of the sclerotic ring in dibamids, rhineurids, and snakes.

It has also been suggested that the lack of sclerotic rings in some lineages (e.g. snakes and placental mammals) is the result of differing modes of accommodation. For examples, mammals lack the corneal accommodation seen in reptiles with a sclerotic ring (Ott, 2005). Snakes also lack corneal accommodation, and although some research suggests they accommodate via lens displacement, this area needs re‐evaluation (Walls, 1942; Ott, 2005). Therefore, it is possible that non‐corneal modes of accommodation may also drive the loss of the sclerotic ring during evolution in addition to a nocturnal or fossorial behaviour.

Here, we show that scotopic species (those that live in low‐light environments, such as nocturnal species and fossorial species who spend most of their life underground) have sclerotic rings with large inner and outer ring diameters (Fig. 4). Even when comparing photopic and scotopic sclerotic rings of similar outer diameters, scotopic species tend to have larger inner diameters, resulting in a narrower ring of bone (Fig. 4). A narrow and thin sclerotic ring likely would provide little structural support, and bone is also metabolically expensive to make. Therefore this trend may have become more extreme in the scotopic lineages that subsequently evolved to lose the sclerotic ring. There is recent evidence that nocturnal behaviour is present at the base of Synapsida (e.g. Angielczyk & Schmitz, 2014), and further investigation into the robustness of the sclerotic ring in this lineage may indicate that nocturnal behaviour is the first step towards losing the sclerotic ring.

The morphology of the sclerotic ring as an indicator of environment and behaviour

Even after accounting for body size, scotopic species have significantly larger sclerotic rings than photopic species, and non‐fossorial species have significantly larger sclerotic rings than fossorial species. This result was not unexpected, as both Hall (2008a,b, 2009) and Schmitz & Motani (2011a) have shown that scotopic birds, lizards, and archosaurs have comparatively larger apertures than photopic species. This is probably because, as has been shown (e.g. Hall, 2009), the aperture measurement is associated with the corneal diameter, and the cornea is larger in scotopic species. Importantly, Hall (2008a, 2009) only measured the corneal diameter (soft tissues) and not the sclerotic ring itself. Schmitz & Motani (2011a), on the other hand, examined extinct and extant species of archosaurs (only), to infer diel activity in extinct species. Our study strictly considers the relationship between the inner and outer diameters of the hard tissue of the ossicle itself, something that has not been done to date in squamates. Here, we measured the inner and outer aperture of the sclerotic ring in 30 extant squamate genera (100 specimens). We found that our results agree with both Hall (2008a,b, 2009)'s analysis of soft tissues in squamates and Schmitz & Motani (2011a)'s hard tissue analysis in archosaurs. Although there has been some argument in the literature on whether or not the sclerotic ring is a valid measurement for discerning diel activity (e.g. Hall, 2009; Hall et al. 2011; Schmitz & Motani, 2011a,b), through our analyses we have clearly shown that although there is some overlap between photopic and scotopic species (also shown by Hall, 2008a, 2009), the size of the ring is significantly different between scotopic and photopic species, and between fossorial and non‐fossorial species. It is currently unknown whether those species with a wider range of diel activities (e.g. cathemeral species) will follow similar trends.

Using only two simple measurements of the sclerotic ring (i.e. the inner and outer diameter alone and omitting orbital length), our results show that it may be possible to draw inferences about the diel activity of fossil species with intact sclerotic rings using similar methods to Schmitz & Motani (2011a). Paleontologists faced with disarticulated skeletons are more likely able to obtain these two measures of the ossicle ring itself rather than the previously used three measures that include orbital length. Further research (e.g. using phylogenetically informed statistics) is needed to explore more fully the scleral ossicle trait in squamates.

Concluding remarks

The distribution of sclerotic rings among squamates supports the loss or reduction of the sclerotic ring via convergent evolution in dibamids, amphisbaenians, and snakes (Figs 2 and 3). These lineages share many derived morphological traits that are thought to be the result of a head‐first burrowing lifestyle, such as the reduction or loss of limbs, elongation of the body, reinforcement and simplification of the skull bones, and miniaturization (Lee, 1998; Coates & Ruta, 2000; Gauthier et al. 2012). The current developmental evidence also supports the loss of scleral ossicles. Regardless of the selection pressures driving the evolution of headfirst burrowing, a decreased reliance on vision may indirectly result in the loss and/or reduction of the sclerotic ring in these lineages. Furthermore, we show that scotopic species have larger sclerotic rings that are often comparatively narrower than those of photopic species, and non‐fossorial species have larger sclerotic rings than fossorial species. The evo‐devo evidence presented above provides support for three individual losses of the sclerotic ring within squamates. With this large dataset established, further research can now be conducted using phylogenetically informed statistics to examine the potential correlation between the scleral ossicle trait and the ecology of squamates.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Family and higher‐level morphology‐based phylogeny of extant squamates modified from Gauthier et al. (2012), and Mo et al. (2010).

Table S1. Summary of fossil species complete enough to assess for presence of the sclerotic ring (n = 19).

Table S2. Lineages that are photopic or scotopic, and lineages have fossorial and limbless members.

Table S3. Genus and species for each specimen measured at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History (USNM) and the Museum of National History (UK) (NMHUK).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tim Fedak, Ron Russell and Susan Meek for their guidance while J.A. completed her studies. Additional thanks to Wynn Addison of The National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution and Patrick Campbell of the Museum of Natural History (UK) for granting J.A. access to these museum collections. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers who provided helpful insights that improved this manuscript. We would also like to thank Saint Mary's University's Faculty of Graduate Studies, Faculty of Biology and Student Association for funding J.A.'s attendance to the Canadian Society of Zoology's Annual Meeting in 2014. This research was funded by a grant awarded to T.F.O. by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

References

- Angielczyk KD, Schmitz L (2014) Nocturnality in synapsids predates the origin of mammals by over 100 million years. Proc R Soc B 281, 20141642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer G (1937) The Development of the Vertebrate Skull. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolet A, Evans SE (2012) A tiny lizard (Lepidosauria, Squamata) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain. Palaeontology 55, 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Caprette CL, Lee MSY, Shine R, et al. (2004) The origin of snakes (Serpentes) as seen through eye anatomy. Biol J Linnean Soc 81, 469–482. [Google Scholar]

- Castanhinha R, Araújo LCJ, Angielczyk KD, et al. (2013) Bringing dicynodonts back to life: paleobiology and anatomy of a new emydopoid genus from the Upper Permian of Mozambique. PLoS One 8, e80974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates MI, Ruta M (2000) Nice snake, shame about the legs. Trends Ecol Evol 15, 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad JL (2008) Phylogeny and systematics of Squamata (Reptilia) based on morphology. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 310, 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- Coulombre AJ, Coulombre JL, Mehta H (1962) The skeleton of the eye. I. Conjunctival papillae and scleral ossicles. Dev Biol 5, 382–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis EL, Miller RC (1938) The sclerotic ring in North American birds. Auk 55, 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter AD, Jovelin R (2015) When natural selection gives gene function the cold shoulder. BioEssays 37, 1169–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duench K, Franz‐Odendaal TA (2012) BMP and Hedgehog signaling during the development of scleral ossicles. Dev Biol 365, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger T (1929) Uber knocherne Scleralringe. Zool Jb 51, 163–226. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Barbadillo LJ (1998) An unusual lizard (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Early Cretaceous of Las Hoyas, Spain. Zool J Linn Soc 124, 235–265. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Wang Y (2010) A new lizard (Reptilia: Squamata) with exquisite preservation of soft tissue from the Lower Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China. J Syst Palaeontol 8, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Wang Y, Li C (2005) The early Cretaceous lizard genus Yabeinosaurus from China: resolving an enigma. J Syst Palaeontol 3, 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández MS, Archuby F, Talevi M, et al. (2005) Ichthyosaurian eyes: paleobiological information content in the sclerotic ring of Caypullisaurus (Ichthyosauria, Ophthalmosauria). J Vert Paleontol 25, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Franz‐Odendaal TA (2006) Intramembranous ossification of scleral ossicles in Chelydra serpentina . Zoology 109, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz‐Odendaal TA (2008a) Scleral ossicles of Teleostei: evolutionary and developmental trends. Anat Rec 291, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz‐Odendaal TA (2008b) Toward understanding the development of scleral ossicles in the chicken, Gallus gallus . Dev Dynam 237, 3240–3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz‐Odendaal TA (2011) The ocular skeleton through the eye of evo‐devo. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 316B, 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz‐Odendaal TA, Hall BK (2006) Skeletal elements within teleost eyes and a discussion of their homology. J Morphol 267, 1326–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C (1978) The characteristics and affinities of the Amphisbaenia. J Zool 34, 347–416. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier JA, Kearney M, Maisano JA, et al. (2012) Assembling the squamate tree of life: perspectives from the phenotype and the fossil record. Bull Peabody Mus Nat Hist 53, 3–308. [Google Scholar]

- Gerkema M, Davies WIL, Foster RG, et al. (2013) The nocturnal bottleneck and the evolution of activity patterns in mammals. Proc R Soc B 280, 4115–4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer AE (1985) The relationships of the lizard genera Anelytropsis and Dibamus . J Herpetol 19, 116–156. [Google Scholar]

- Greer AE (1991) Limb reduction in squamates: Identification of the lineages and discussion of the trends. J Herp 25, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI (2008a) Comparative analysis of the size and shape of the lizard eye. Zoology 111, 62–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI (2008b) The anatomical relationships between the avian eye, orbit and sclerotic ring: implications for inferring activity patterns in extinct birds. J Anat 212, 781–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI (2009) The relationship between the lizard eye and associated bony features: a cautionary note for interpreting fossil activity patterns. The Anat Rec 292, 798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI, Kirk EC, Kamilar JM, Carrano MT (2011) Comment on Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology. Science 334, 1641–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK (2014) Bones and Cartilage: Developmental and Evolutionary Skeletal Biology. London: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdeuil K, Franz‐Odendaal TA (2012) Vasculogenesis and the induction of skeletogenic condensations in the avian eye. Anat Rec 295, 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M (2003) Systematics of the Amphisbaenia (Lepidosauria: Squamata) based on morphological evidence from recent and fossil forms. Herpetol Monogr 17, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MSY (1998) Convergent evolution and character correlation in burrowing reptiles: towards a resolution of squamate relationships. Biol J Linnean Soc 65, 369–453. [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Hipsley CA, Head JJ, et al. (2011) Eocene lizard from Germany reveals amphisbaenian origins. Nature 473, 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PDF (1943) The development of the conjunctival papillae and of the scleral bones in the embryo chick. J Anat 77, 225–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhauss SC, Solnica‐Krezel L, Schier AF, et al. (1996) Mutations affecting craniofacial development in zebrafish. Development 123, 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M (2005) Visual accommodation in vertebrates: mechanisms, physiological response and stimuli. J Comp Physiol A 192, 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim BL, Franz‐Odendaal TA (2009) A comparative study of the ocular skeleton of fossil and modern chondrichthyans. J Anat 214, 848–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyron RA, Burbrink FT, Wiens JJ (2013) A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes. BMC Evol Biol 13, 1–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe TB (1988) Definition, diagnosis, and origin of Mammalia. J Vert Paleontol 8, 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz L, Motani R (2011a) Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology. Science 332, 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz L, Motani R (2011b) Response to comment on ‘Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology’. Science 334, 1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood G (1970) The eye In: Biology of the Reptilia: Morphology B. (eds Gans C, Parsons TS.), pp. 1–97, New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood G (1984) Scleral ossicles in lizards: An exercise in character analysis In: The Structure, Development and Evolution of Reptiles (ed. Ferguson MWJ.), pp. 483–502. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Urben CC, Daza JD, Cadena C, et al. (2014) The homology of the pelvic elements of Zygaspis quadrifrons (Squamata: Amphisbaenia). Anat Rec 297, 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls GL (1942) The Vertebrate Eye and its Adaptive Radiation. Bloomfield Hills: Cranbrook Institute of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Brandley MC, Reeder TW (2006) Why does a trait evolve multiple times within a clade? Repeated evolution of snakeline body form in squamate reptiles. Evolution 60, 123–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Kuczynski CA, Townsend TM, et al. (2010) Combining phylogenomics and fossils in higher‐level squamate reptile phylogeny: molecular data change the placement of fossil taxa. Syst Biol 59, 674–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Family and higher‐level morphology‐based phylogeny of extant squamates modified from Gauthier et al. (2012), and Mo et al. (2010).

Table S1. Summary of fossil species complete enough to assess for presence of the sclerotic ring (n = 19).

Table S2. Lineages that are photopic or scotopic, and lineages have fossorial and limbless members.

Table S3. Genus and species for each specimen measured at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History (USNM) and the Museum of National History (UK) (NMHUK).