Abstract

Background/aim

Diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) is defined as a separation of the 2 muscle bellies of rectus abdominis. To date there is scant knowledge on prevalence, risk factors, and consequences of the condition. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of DRA during pregnancy and post partum, presence of possible risk factors, and the occurrence of lumbopelvic pain among women with and without DRA.

Methods

This prospective cohort study followed 300 first-time pregnant women from pregnancy till 12 months post partum. Data were collected by electronic questionnaire and clinical examinations. DRA was defined as a palpated separation of ≥2 fingerbreadths either 4.5 cm above, at or 4.5 cm below the umbilicus. Women with and without DRA were compared with independent samples Student's t-test and χ2/Fisher exact test, and OR with significance level >0.05.

Results

Prevalence of DRA was 33.1%, 60.0%, 45.4%, and 32.6% at gestation week 21, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post partum, respectively. No difference in risk factors was found when comparing women with and without DRA. OR showed a greater likelihood for DRA among women reporting heavy lifting ≥20 times weekly (OR 2.18 95% CI 1.05 to 4.52). There was no difference in reported lumbopelvic pain (p=0.10) in women with and without DRA.

Conclusions

Prevalence of mild DRA was high both during pregnancy and after childbirth. Women with and without DRA reported the same amount of lumbopelvic pain 12 months post partum.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Risk factor, Abdomen, Pelvic, Lower back

Introduction

Diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) is defined as a separation of the two muscle bellies of rectus abdominis.1 DRA is often described in relation to pregnancy, but occurs both in postmenopausal women2 and in men.3 4 Search on PubMed revealed only few studies on DRA prevalence during pregnancy and in the postpartum period,2 5–9 and the prevalence rates varied in the identified studies. To date, there is also scant knowledge about risk factors, but factors such as high age, multiparity, caesarean section, weight gain, high birth weight, multiple pregnancy, ethnicity, and childcare have been proposed.2 8–11 There are few studies investigating risk factors for having DRA in a timespan of >6 months post partum and there is scant knowledge on the consequences of DRA. It has been claimed that DRA may change posture and give more back strain due to reduced strength and function, leading to low back pain.12 13 However, some studies also contradict this hypothesis.5 14 In addition, there is increasing focus on how women can regain a ‘flat tummy’ after childbirth. The sparse scientific knowledge in this area is in great contrast to the information and opinions women are exposed to in social media regarding abdominal exercise related to DRA. Hence, there is a need for studies on prevalence, risk factors, possible consequences, and the effects of abdominal training in prevention and treatment of the condition.15

The aims of the present study were: (1) to investigate the prevalence of DRA among nulliparous pregnant women during pregnancy and the first year post partum; (2) to investigate the presence of possible risk factors among women with and without DRA 12 months post partum and (3) to investigate report of lumbopelvic pain among women with and without DRA 12 months post partum.

Methods

The study was part of a cohort study at Akershus University Hospital (Ahus), Norway. All first-time mothers with planned birthplace at the hospital in the period from January 2010 to April 2011 were invited to participate in the study.16 17 Data were collected by electronic questionnaire at gestation week 21 in addition to 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post partum. At these four assessment points, clinical examinations were carried out by two physiotherapists. Data on delivery mode and the baby’s birth weight were collected from the women's electronic medical journal at the hospital. The cohort study was approved by the Regional Medical Ethics Committee (2009/170), and the Data Protection Officer at Ahus (2799026). All women gave written informed consent before entering the study and procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (2008). The study followed the STROBE reporting guidelines.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

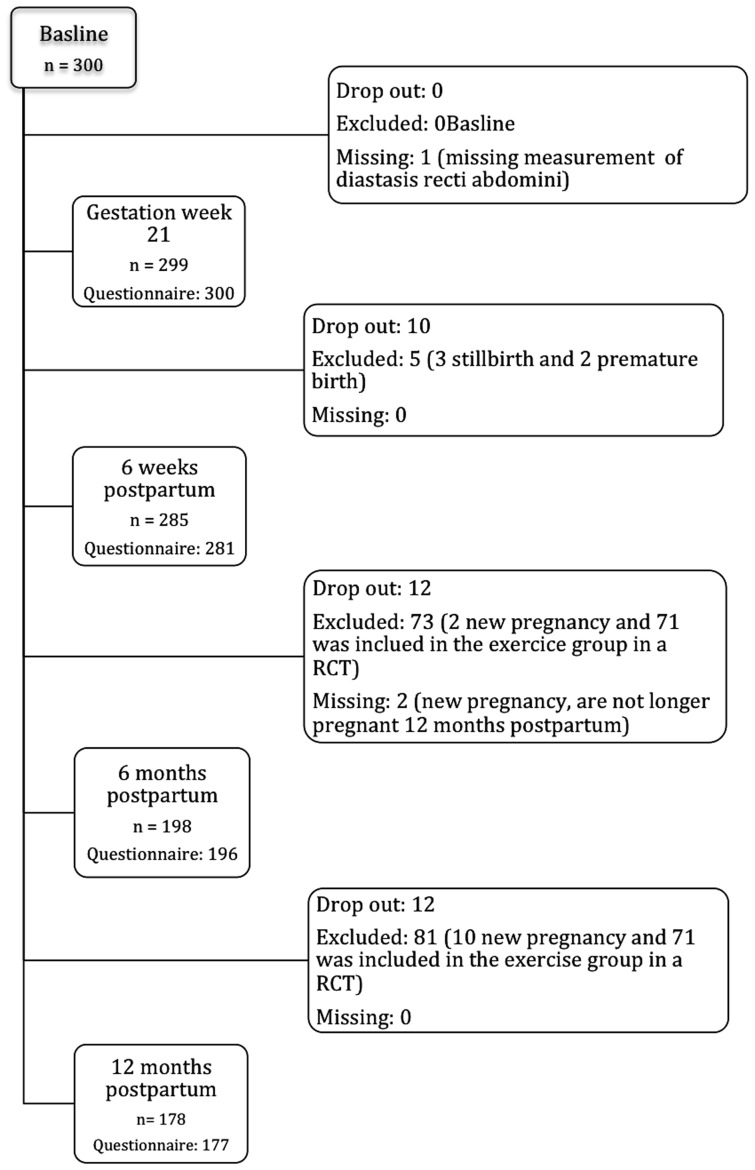

The inclusion took place in conjunction with the routine ultrasound examination at gestation week 18–22. Inclusion criteria were women aged ≥18 years, and the ability to understand and speak a Scandinavian language. Exclusion criteria at baseline were serious illnesses, multiple pregnancies, and history of a previous pregnancy lasting >16 weeks. During the study period women with spontaneous abortion, stillbirth or premature birth before gestation week 32 were excluded and women included in the training group in a parallel randomised controlled trial (RCT) on pelvic floor muscles training starting 6 weeks post partum were excluded.18 Additionally, data from women with a new pregnancy of >6 weeks gestation were excluded from the analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Power calculation

The study was a planned part of a project addressing several questions related to the pelvic floor during pregnancy and after childbirth. Whereas the power calculation for the cohort study was based on expected changes in the levator hiatus area, assessed by ultrasound,19 there was no a priori power calculation for the present study on DRA.

Measurement of DRA and cut-off value

All clinical examinations were performed by two physiotherapists blinded to data collected through the questionnaire. Owing to practical reasons the physiotherapist did not necessarily follow the same women throughout the study period. DRA was measured by palpation 4.5 cm above, at and 4.5 cm below the umbilicus.6 The women were tested in a standardised supine crock-lying position with arms crossed over the chest. They were instructed to perform an abdominal crunch till the shoulder blades were off the bench. Palpation of DRA in postpartum women has shown to have good intrarater reliability (Kw>0.70) and moderate inter-rater reliability (Kw=0.53).20

The women were classified into four categories depending on the largest measured inter-recti distance among the three locations: (1) non-DRA was set as a separation <2 fingerbreadths, (2) mild diastasis as a separation of 2–3 fingerbreadths, (3) moderate diastasis as 3–4 fingerbreadths and (4) severe diastasis as a separation of 4 or more fingerbreadths. Observed protrusion along the linea alba was categorised as DRA even if the palpated distance was <2 fingerbreadths. The categorising was based on the study by Candido et al.8 Prevalence of DRA was analysed as yes/no and mild, moderate and severe grade of DRA were merged in the main analysis.

Risk factors

Selection of risk factors was based on existent literature and clinical reasoning. The chosen variables were: age, height, mean weight before this pregnancy, weight gain during pregnancy, delivery mode, baby's birth weight, benign joint hypermobility syndrome, heavy lifting, and level of abdominal and pelvic floor muscle exercise training and general exercise training 12 months post partum.

Hypermobility was assessed with Beighton score, including nine subtests: trunk flexion with palms flat on the floor, hyperextension of left/right elbow past 10°, hyperextension of left/right knee past 10°, passive movement of left/right thumb up to the forearm, and passive extension of fifth left/right metacarpophalangeal joint past 90°.21 Each subtest is graded zero or one. Maximum test score is 9 points and cut-off for hypermobility was set to 5/9.22–26 Beighton test has shown good intrarater (Spearman r 0.86) and inter-rater (Spearman r 0.87) reliability examined in women 15–45 years of age.22

Lumbopelvic pain

Pain related to the low back and pelvic girdle was recorded by using an electronic questionnaire. Two yes/no questions were used: ‘Are you bothered with pain in the low back?’ and ‘Are you bothered with pain in the pelvis?’ If answering ‘yes’ on pelvic girdle pain, participants were further asked to localise the pain with the following alternatives: (1) right posterior pelvic pain, (2) left posterior pelvic pain, (3) bilateral posterior pelvic pain and/or (4) anterior pelvic pain. Pelvic girdle syndrome was defined as having anterior and bilateral posterior pain.27 In the main analysis, low back pain and/or pelvic girdle pain were conflated into lumbopelvic pain. Additionally, subanalysis of either pelvic girdle pain or low back pain was performed independently.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (V.21, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Background variables were reported as means with SDs or frequencies, and percentages. Women with and without DRA were compared in relation to risk factors with independent sample Student's t-test for numeric data and χ2/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to calculate ORs for the different risk factors reported as OR with 95% CI. Spearman’s correlation between variables was used to investigate the basis for adjustments for possible confounding factors. Differences in report of lumbopelvic pain were compared with Fisher’s exact test. Missing data were excluded. The significance level was set to >0.05.

Results

In total, 2621 women were scheduled for delivery at Ahus during the inclusion period. The cohort consisted of 300 primiparous women of European ethnicity (96%), and between 19 and 40 years of age (table 1). The prevalence of DRA was 33.1% at gestation week 21, 60.0% 6 weeks post partum, 45.5% 6 months post partum, and 32.6% 12 months post partum (table 2). The location with the highest prevalence of DRA was at the umbilicus for all the time points.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of 300 nulliparous women with planned birthplace at Akershus University Hospital, Norway

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (±SD) | 28.7±4.3 |

| Weight before this pregnancy (kg) (±SD) | 67.2±12.1 |

| BMI before this pregnancy (m/kg2) (±SD) | 23.9±3.9 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabitant (n (%)) | 287 (95.7) |

| Single or divorced (n (%)) | 13 (4.3) |

| Educational level | |

| College/university (n (%)) | 226 (75.3) |

| Primary school, high school or other (n (%)) | 74 (24.7) |

| Smoking before this pregnancy | |

| Yes, daily (n (%)) | 33 (11.0) |

| Yes, sometimes (n (%)) | 44 (14.7) |

| No (n (%)) | 223 (74.3) |

| General cardio exercise before this pregnancy (n (%)) | |

| <20 min 3 times weekly high or 30 min 5 times weekly moderate intensity | 183 (61) |

| ≥20 min 3 times weekly high or 30 min 5 times weekly moderate intensity | 117 (39) |

| General strength exercise before this pregnancy (n (%)) | |

| <2 times weekly | 245 (81.7) |

| ≥2 times weekly | 55 (18.3) |

| Working before this pregnancy (n (%)) | |

| Yes (including the women who were on sick leave, n=11) | 277 (92.3) |

| No (homemaker, job seeker or student) | 23 (7.7) |

Numbers with percentages (%), mean with SD.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis categorised as normal, mild, moderate and severe

| Classification of diastasis recti abdominis | Gestation week 21 n=299 |

6 weeks post partum n=285 |

6 months post partum n=198 |

12 months post partum n=178 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 200 (66.9) | 114 (40) | 108 (54.6) | 120 (67.4) |

| Mild | 91 (30.4) | 154 (54) | 88 (44.4) | 56 (31.5) |

| Moderate | 8 (2.7) | 16 (5.6) | 2 (1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Numbers (n) with percentages (%).

Table 3 showed no significant difference in evaluated risk factors when comparing women with and without DRA 12 months post partum. There were three borderline values: height, heavy lifting and participation in strength exercise training. The OR for DRA was twice as high among women reporting heavy lifting 20 times a week or more than that for women reporting less weight lifting (table 4). No other significant risk factors were found.

Table 3.

Possible risk factors compared between women with and without diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) 12 months post partum

| Variable | DRA n=57 |

No DRA n=120 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (±SD) | 28.0±4.3 | 29.1±4.3 | 0.11 |

| Height (cm) (±SD) | 169±5.7 | 167.2±6.3 | 0.05 |

| Mean weight before this pregnancy (kg) (±SD) | 66.1±11.9 | 67.3±12,1 | 0.55 |

| Weight gain from prepregnancy to gestation week 37 (kg) (±SD) | 15.3±5.6 | 15.0±4.5 (n=108) | 0.80 |

| Baby's birth weight (g) (±SD) | 3537±508 | 3454±527 | 0.32 |

| Delivery mode | |||

| Vaginal (n (%)) | 45 (78.9) | 98 (81.7) | 0.69 |

| Caesarean section (n (%)) | 12 (21.1) | 22 (18.3) | |

| Hypermobility | |||

| Hypermobility (n (%)) | 13 (22.8) | 14 (11.7) | 0.07 |

| No hypermobility (n (%)) | 44 (77.2) | 106 (88.3) | |

| General cardio exercise 12 months post partum (n (%)) | |||

| <20 min 3 times weekly high or 30 min 5 times weekly moderate intensity | 41 (71.9) | 91 (75.8) | 0.58 |

| ≥20 min 3 times weekly high or 30 min 5 times weekly moderate intensity | 16 (28.1) | 29 (24.2) | |

| General strength exercise 12 months post partum (n (%)) | |||

| <2 times weekly | 54 (94.7) | 97 (80.8) | 0.05 |

| ≥2 times weekly | 3 (5.3) | 23 (19.2) | |

| Abdominal exercise 12 months post partum (n (%)) | |||

| Never/seldom | 41 (71.9) | 75 (62.5) | 0.09 |

| 1 time per week | 10 (17.5) | 15 (12.5) | |

| 2 times per week | 3 (5.3) | 21 (17.5) | |

| ≥3 times per week | 3 (5.3) | 9 (7.5) | |

| Pelvic floor muscle exercise 6–12 months post partum (n (%)) | |||

| Never/when needed | 41 (71.9) | 75 (62.5) | 0.07 |

| 1 time per week | 10 (17.5) | 17 (14.2) | |

| 1–2 times per week | 3 (5.3) | 12 (10.0) | |

| ≥3 times per week | 3 (5.3) | 16 (13.3) | |

| Heavy lifting (n (%)) | |||

| <20 times per week | 39 (68.4) | 99 (82.5) | 0.05 |

| ≥20 times per week | 18 (31.6) | 21 (17.5) | |

Numbers (n) with percentages (%), mean with SD.

Table 4.

OR with 95% CI for risk factors compared between women with and without diastasis recti abdominis 12 months post partum

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.02) | 0.11 |

| Height (cm) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) | 0.05 |

| Mean weight before this pregnancy (kg) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) | 0.54 |

| Weight gain from prepregnancy to gestation week 37 (kg) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.80 |

| Baby's birth weight (g) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.32 |

| Caesarean section (elective and acute) | 1.19 (0.54 to 2.61) | 0.69 |

| Hypermobility (yes/no) | 2.24 (0.97 to 5.14) | 0.06 |

| General cardio exercise 12 months post partum | 1.23 (0.60 to 2.50) | 0.58 |

| General strength exercise 12 months post partum | 0.30 (0.08 to 1.04) | 0.06 |

| Abdominal exercise 12 months post partum (n (%)) | ||

| Never/seldom | ||

| 1 time per week | 1.64 (0.42 to 6.39) | 0.48 |

| 2 times per week | 2.00 (0.43 to 9.26) | 0.38 |

| ≥3 times per week | 0.43 (0.72 to 2.54) | 0.35 |

| Pelvic floor muscle exercise 6–12 months post partum (n (%)) | ||

| Never/when needed | ||

| 1 time per week | 2.91 (0.80 to 10.61) | 0.16 |

| 1–2 times per week | 3.14 (0.73 to 13.5) | 0.13 |

| ≥3 times per week | 1.33 (0.23 to 7.80) | 0.75 |

| Heavy lifting ≥20 times per week | 2.18 (1.05 to 4.52) | 0.04 |

Table 5 showed no difference in lumbopelvic pain among women with and without DRA 12 months post partum. Four women had pelvic girdle syndrome, and one woman had pain in the front and back on one side.

Table 5.

Report of low back pain and pelvic girdle pain among women with and without diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) 12 months post partum

| Variable | DRA n=57 |

No DRA n=120 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbopelvic pain | |||

| Yes (n (%)) | 26 (45.6) | 39 (32.5) | 0.10 |

| No (n (%)) | 31 (54.4) | 81 (67.5) | |

| Low back pain and pelvic girdle pain | |||

| Yes, both (n (%)) | 5 (8.8) | 11 (9.2) | 1.00 |

| No, or just one of them (n (%)) | 52 (91.2) | 109 (90.8) | |

| Low back pain only | |||

| Yes (n (%)) | 22 (38.6) | 33 (27.5) | 0.17 |

| No (n (%)) | 35 (61.4) | 87 (72.5) | |

| Pelvic girdle pain only | |||

| Yes (n (%)) | 9 (15.8) | 17 (4.2) | 0.82 |

| No (n (%)) | 48 (84.2) | 103 (85.8) | |

Numbers (n) with percentages (%).

Lumbopelvic pain, low back pain and/or pelvic girdle pain.

Discussion

At gestation week 21, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post partum, the prevalence of DRA was 33.1%, 60.0%, 45.4% and 32.6%, respectively. There was a greater likelihood for DRA among women reporting to be exposed to heavy lifting 20 times a week or more calculated with OR, but no other risk factors were found to be statistically significant. Women with DRA were not more likely to report lumbopelvic pain compared with women without DRA.

Prevalence of DRA

There is no universal agreement about the definition of DRA,15 28 and variance in prevalence rates between studies can be explained by use of different cut-off values and locations along the linea alba,11 29 degree of abdominal muscle activation during the measurement,30 31 use of different measurement tools,20 parity,2 9–11 29 and populations studied. The chosen cut-off value for DRA in the present study is in accordance with several studies investigating similar populations,6–8 10 and the chosen measurement location is used frequently.6 14 32 33

We have only identified two studies investigating the prevalence of DRA during pregnancy.5 6 Our result of 33.1% is in accordance with Boissonnault and Blaschak’s6 results of a prevalence of 27% in the second trimester. They assessed DRA with palpation at the same three locations along linea alba, and with similar cut-off values as the present study. Mota et al5 measured DRA with ultrasound during gestational week 35, and reported a prevalence of 100%. The difference in measurement method, assessment-time, and the use of 1.6 cm as cut-off value makes direct comparison between studies difficult. To the best of our knowledge, Mota et al5 is the only study reporting prevalence of DRA 6 weeks and 6 months post partum. Their results of 52.4% and 39% are lower than our result of 60% and 45.4% at the same time points. Boissonnault and Blaschak’s,6 who measured DRA 5 weeks to 3 months post partum, reported a prevalence of 36%.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the only one assessing DRA 1 year post partum. Turan et al9 examined DRA with palpation minimum 6 months post partum and reported a prevalence of 19.7% when applying a cut-off of 2 fingerbreadths or more 3–4 cm above the umbilicus. Using the same location, the present study found a prevalence of 10.2% measured 1 year post partum (data not shown), and among all three measurement locations our result was 32.6%.

Possible risk factors for DRA 12 months post partum

Our data shows no clear risk factors for DRA 12 months post partum. The wide CI for the OR on heavy lifting indicates that this result should be interpreted with caution. In support, the same variable was only on the borderline using Fisher’s exact test and due to the multiple variables investigated in this study, the risk of a type I error is increased.34 Data on heavy lifting was collected through the questionnaire, and was neither defined nor measured directly. Some authors have discussed how frequent lifting and carrying children may cause increased strain on the abdominal wall and DRA, without providing any direct data for this hypothesis.8 Hence, this proposed risk factor needs further investigation. There was no correlation between possible confounding factors and DRA or investigated risk factors; therefore, it was considered to be of no basis for calculating adjusted OR.

When comparing women with and without DRA in the present study, no difference was found in the number of women fulfilling the recommendations for general exercise, strength training or specific pelvic floor muscle training 1 year post partum. With a prevalence of DRA of above 30% at 12 months post partum, preventive and treatment strategies are likely to develop. As we did not perform a RCT we cannot, based on our data, advice women on how to prevent or treat the condition. A recent systematic review concluded that, as for now, there are no high-quality RCTs on the effect of abdominal training programmes to guide clinical practice in this area.15 Further high-quality studies regarding this prevalent condition within women's health and exercise training are therefore warranted.

In accordance with Mota et al,5 our study showed no association between report of regular exercise and DRA. Discordantly, Candido et al8 found that women with mild or no DRA were more often engaged in regular vigorous exercise three times a week or more, and in regular walking exercise during pregnancy as compared with women with moderate or severe DRA. In our sample, there were only two women with moderate DRA and none with severe DRA 12 months post partum. The fact that the majority of women had a mild DRA could be a reason for not seeing any differences between the groups regarding all the risk factors. The use of different categories of exercise may also explain the disparate results. We used the American College of Sports Medicine's guidelines for exercise when setting cut-off value for frequency of exercise.35 Other factors that may be protective against more severe diastasis in our population is the inclusion of only primiparous women carrying a single fetus. Lo et al10 found that twin pregnancy was a risk factor for DRA; however, this was not supported by the study of Candido et al.8

Lumbopelvic pain 12 months post partum

Several authors have postulated a relationship between DRA and low back pain,9 12 13 36–38 but the evidence for such an association is scant.14 Our result showed no difference between women with and without DRA, and prevalence of low back and/or pelvic girdle pain. This is in accordance with Mota et al5 and Parker et al.14 However, the latter study found an association between DRA and abdominal and pelvic region pain, and argued that the observation of no associations between DRA and low back pain might be due to inclusion of women with non-severe DRA. The maximal separation in their study was 5.02 cm, which is comparable to our result where only one woman had a separation greater than 4 fingerbreadths. Another explanation for the result of no association may be the small sample size in our study.

Strengths and limitations

The longitudinal design and blinding of assessors to symptoms and risk factors can be considered strengths of the study. In addition, we had a large sample size compared with other published studies in the postpartum period,5 6 and also investigated a sample of homogeneous primiparous women. Furthermore, two trained physiotherapists who were aware of the pitfalls of the palpation method conducted the study.

Palpation has been found to have moderate inter-rater reliability, and may be considered a limitation of the study.20 Today, ultrasound is recommended as a more responsive and reliable method to assess inter-recti distance.20 39 However, Van de Water and Benjamin40 argued that palpation may be a sufficient method for detecting presence of DRA. This was the main purpose of our study in addition to comparing risk factors and lumbopelvic pain in women with and without diastasis. Palpation is the most commonly used method in clinical practice,41 and the results may therefore be considered clinically understandable and relevant for most practitioners. However, we support the recommendations for use of ultrasound for more details of DRA in future studies.20

Another limitation of the present study is the lack of data on the normal width of linea alba before pregnancy. However, earlier studies have shown no prevalence of DRA among nulliparous women using similar cut-off values.6 9 Furthermore, the use of questionnaire to diagnose low back and pelvic girdle pain may be a limitation as the diagnosis pelvic girdle pain is recommended to be confirmed through specific clinical tests.42 The use of questionnaire for exercise data is also a potential source of bias as the questions related to exercise may be prone to recall bias43 and overestimation.44 However, the recall bias in the present study was highest for prepregnancy data, and it is considered that use of questionnaires can help separate between participants fulfilling recommendations for exercise and not.43 The questions used regarding exercise are similar to those developed for the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.45 In general, there has to be caution in determining risk factors from questionnaire data; however, questionnaires are a commonly used, easy and cost-effective way of collecting information.43 Regarding the weight-related data, one weakness is that there was no direct measure of the strain on the abdominal wall. Furthermore, abdominal circumference and symphysis fundus measurements could have been relevant.

Generalisability of the present study is limited because of the homogeneity of the participants included. There were no a priori power calculation for the investigated variables, but the study is one of the few longitudinal studies in the peripartum period and future power calculations can be based on results from the present study. Given the high prevalence of DRA post partum, and the concern and focus on the abdominal muscle after childbirth, there is a need for more scientifically based knowledge on consequences, prevention, and treatment of the condition. Our study did not confirm that mild diastasis caused lumbopelvic pain. However, to date, there is little knowledge on women with larger separation. Further investigation using a validated questionnaire on low back and pelvic pain in conjunction with more objective testing is required to conclusively prove this association.

Conclusion

Prevalence of mild DRA was high both during pregnancy and after childbirth. No obvious risk factors were found, and there was no difference in report of lumbopelvic pain between the group with and without DRA 12 months post partum. There is a need for more research on the influence of DRA on abdominal strength and lumbopelvic pain, and the effect of preventative and treatment programmes.

What are the findings?

Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) among first-time pregnant Scandinavian women were 33.1%, 60.0%, 45.4% and 32.6% at gestation week 21, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post partum, respectively.

Age, height, mean weight before this pregnancy, weight gain during pregnancy, caesarean section, baby's birth weight, benign joint hypermobility syndrome, and level of abdominal and pelvic floor muscle exercise training and general exercise training 12 months post partum were not found to be risk factors for DRA.

Women with DRA were not more likely to report lumbopelvic pain compared with women without DRA 12 months after childbirth.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the future?

Given the high prevalence of mild diastasis recti abdominis, coaches and healthcare providers should assess whether the condition is present in post partum women.

This study indicates that mild diastasis is not associated with lumbopelvic pain, which is important information to give to women with this condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank professor of biostatistics, Ingar Holme, Department of Sports Medicine, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, for valuable advice on statistical analyses; gynaecologist Cathrine Reimers for cleaning of data and data entry; physical therapist Kristin Gjestland, and midwife Tone Breines Simonsen for recruiting participants, clinical testing, and data entry; and gynaecologists Jette Stær-Jensen and Franziska Siafarikas for clinical testing and data entry.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have contributed to the reporting of the work described in the article. JBS and KB are guarantors.

Funding: The study was funded by the South-Eastern Regional Health Authority and the Research Council of Norway.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Regional Medical Ethics Committee (2009/170).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Venes D, Taber CW. Taber's cyclopedic medical dictionary. 20 edn Philadelphia: Davis, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spitznagle TM, Leong FC, Van Dillen LR. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:321–8. 10.1007/s00192-006-0143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockwood T. Rectus muscle diastasis in males: primary indication for endoscopically assisted abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:1685–91; discussion 92–4 10.1097/00006534-199805000-00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, et al. Laparoscopic repair of diastasis recti using the ‘Venetian blinds’ technique of plication with prosthetic reinforcement: a retrospective study. Hernia 2009;13:287–92. 10.1007/s10029-008-0464-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mota P, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Man Ther 2015;20:200–5. 10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boissonnault JS, Blaschak MJ. Incidence of diastasis recti abdominis during the childbearing year. Phys Ther 1988;68:1082–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bursch SG. Interrater reliability of diastasis recti abdominis measurement. Phys Ther 1987;67:1077–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candido G, Lo T, Janssen PA. Risk factors for diastasis of the recti abdominis. J Assoc Chart Physiother Womens Health 2005;97:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turan V, Colluoglu C, Turkyilmaz E, et al. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekol Pol 2011;82:817–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo T, Candido G, Janssen P. Diastasis of the recti abdominis in pregnancy: risk factors and treatment. Physiother Can 1999;51:32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rett MT, Braga MD, Bernardes NO, et al. Prevalence of diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles immediately postpartum: comparison between primiparae and multiparae. Rev Bras De Fisioterapia 2009;13:275–80. 10.1590/s1413-35552009005000037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boissonnault JS, Kotarinos KR. Diastasis recti I. In: Wilder E. ed. Obstetric and gynecologic physical therapy. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1988:63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noble E. Essential exercises for the childbearing year: a guide to health and comfort before and after your baby is born. 4th edn Harwich: New Life Images, 1995:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker MA, Millar AL, Dugan SA. Diastasis rectus abdominis and lumbo-pelvic pain and dysfunction—are they related? J Womens Health Phys Ther 2009;33:15–22. 10.1097/01274882-200933020-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin DR, van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2014;100:1–8. 10.1016/j.physio.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilde G, Staer-Jensen J, Ellstrom Engh M, et al. Continence and pelvic floor status in nulliparous women at midterm pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1257–63. 10.1007/s00192-012-1716-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staer-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Hilde G, et al. Postpartum recovery of levator hiatus and bladder neck mobility in relation to pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:531–9. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilde G, Staer-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, et al. Postpartum pelvic floor muscle training and urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:1231–8. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stær-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Hilde G, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of pelvic organ support during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(Pt 1):329–36. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318299f62c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mota P, Pascoal AG, Sancho F, et al. Reliability of the inter-rectus distance measured by palpation. Comparison of palpation and ultrasound measurements. Man Ther 2013;18:294–8. 10.1016/j.math.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beighton P, Solomon L, Soskolne CL. Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 1973;32:413–18. 10.1136/ard.32.5.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle KL, Witt P, Riegger-Krugh C. Intrarater and interrater reliability of the Beighton and Horan Joint Mobility Index. J Athl Train 2003;38:281–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulbena A, Duro JC, Porta M, et al. Clinical assessment of hypermobility of joints: assembling criteria. J Rheumatol 1992;19:115–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junge T, Jespersen E, Wedderkopp N, et al. Inter-tester reproducibility and inter-method agreement of two variations of the Beighton test for determining generalised joint hypermobility in primary school children. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:214 10.1186/1471-2431-13-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quatman CE, Ford KR, Myer GD, et al. The effects of gender and pubertal status on generalized joint laxity in young athletes. J Sci Med Sport 2008;11:257–63. 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Giessen LJ, Liekens D, Rutgers KJ, et al. Validation of Beighton score and prevalence of connective tissue signs in 773 Dutch children. J Rheumatol 2001;28:2726–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG. Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2831–4. 10.1097/00007632-200212150-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akram J, Matzen SH. Rectus abdominis diastasis. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2014;48:163–9. 10.3109/2000656X.2013.859145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiarello CM, McAuley JA. Concurrent validity of calipers and ultrasound imaging to measure interrecti distance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43:495–503. 10.2519/jospt.2013.4449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbosa S, de Sa RA, Coca Velarde LG. Diastasis of rectus abdominis in the immediate puerperium: correlation between imaging diagnosis and clinical examination. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:299–303. 10.1007/s00404-013-2725-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pascoal AG, Dionisio S, Cordeiro F, et al. Inter-rectus distance in postpartum women can be reduced by isometric contraction of the abdominal muscles: a preliminary case-control study. Physiotherapy 2014;100:344–8. 10.1016/j.physio.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilleard WL, Brown JM. Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Phys Ther 1996;76:750–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiarello CM, Falzone LA, McCaslin KE, et al. The effects of an exercise program on diastasis recti abdominis in pregnant women. J Womens Health Phys Ther 2005;29:11–16. 10.1097/01274882-200529010-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laake P, Olsen BR, Benestad HB. Forskning i medisin og biofag. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2008:264–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:1423–34. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stark B, Emanuelsson P, Gunnarsson U, et al. Validation of Biodex system 4 for measuring the strength of muscles in patients with rectus diastasis. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2012;46:102–5. 10.3109/2000656X.2011.644707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boxer S, Jones S. Intra-rater reliability of rectus abdominis diastasis measurement using dial calipers. Aust J Physiother 1997;43:109–14. 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60405-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalal K, Kaur A, Mitra M. Correlation between diastasis rectus abdominis and lumbopelvic pain and dysfunction. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther 2014;8:210–14. 10.5958/j.0973-5674.8.1.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mota P, Pascoal AG, Sancho F, et al. Test-retest and intrarater reliability of 2-dimensional ultrasound measurements of distance between rectus abdominis in women. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012;42:940–6. 10.2519/jospt.2012.4115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Water AT, Benjamin DR. Measurement methods to assess diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM): a systematic review of their measurement properties and meta-analytic reliability generalisation. Man Ther 2016;21:41–53. 10.1016/j.math.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keeler J, Albrecht M, Eberhardt L, et al. Diastasis recti abdominis: a survey of women's health specialists for current physical therapy clinical practice for postpartum women. J Womens Health Phys Therapy 2012;36:131–42. 10.1097/JWH.0b013e318276f35f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, et al. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J 2008;17:794–819. 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shephard RJ, Aoyagi Y. Measurement of human energy expenditure, with particular reference to field studies: an historical perspective. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012;112:2785–815. 10.1007/s00421-011-2268-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport 2000;71(2 Suppl):S1–14. 10.1080/02701367.2000.11082780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, et al. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1146–50. 10.1093/ije/dyl170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]