Abstract

The modern-day athlete participating in elite sports is exposed to high training loads and increasingly saturated competition calendar. Emerging evidence indicates that inappropriate load management is a significant risk factor for acute illness and the overtraining syndrome. The IOC convened an expert group to review the scientific evidence for the relationship of load—including rapid changes in training and competition load, competition calendar congestion, psychological load and travel—and health outcomes in sport. This paper summarises the results linking load to risk of illness and overtraining in athletes, and provides athletes, coaches and support staff with practical guidelines for appropriate load management to reduce the risk of illness and overtraining in sport. These include guidelines for prescription of training and competition load, as well as for monitoring of training, competition and psychological load, athlete well-being and illness. In the process, urgent research priorities were identified.

Keywords: Training, Training load, Overtraining, Overtraining and burnout, Illness

Introduction and objectives of the consensus

The modern-day elite athlete experiences an ever-increasing and congested sports calendar, and this is coupled with increased training and competition ‘load’. There is a perception among health professionals taking care of athletes that ‘excessive training load’, combined with an ‘overloaded’ or ‘congested’ competition schedule (competition load) exposes athletes in different sports to an inability to adapt optimally to the overall load. This can result in decreased performance and is also associated with an increased risk of injury (Soligard et al, 2016 IOC Injury consensus statement paper) and the development of acute illness and/or the overtraining syndrome (OTS). High-intensity and prolonged training and competition ‘load’ is associated with an increased risk of both subclinical immunological changes that may increase the risk of illness, and actual symptoms of illness or diagnosed illness.1 2 Furthermore, frequent and prolonged international travel, which is part of the modern-day congested sports calendar, may be related to increased risk of illness in athletes.3 4

Epidemiology of in competition acute illness in elite athletes

The epidemiology of acute illness in elite-level athletes during international competition has been studied in a variety of settings including the Summer5 and Winter Olympic Games,6 7 Winter Youth Olympic Games,8 Summer Paralympic Games,9 Winter Paralympic Games10 and other international competitions in a variety of sports including athletics,11 aquatic sports,12 football13 14 and rugby union (table 1).15

Table 1.

Illness incidence proportion (%) among athletes at major competitive events lasting 2–16 weeks

| Games/Competition | Season | Duration (days) | Athletes (n) | Males (n) | Females (n) | All athletes (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | Respiratory (% total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FINA 201516 | Summer | 18 | 2413 | 1151 | 1262 | 12.9 | 11.9 | 13.8 | 34 |

| Paralympics 201410 | Winter | 12 | 547 | 418 | 129 | 17.4 | 17.0 | 18.6 | 30 |

| Olympics 20146 | Winter | 18 | 2780 | 1659 | 1121 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 10.9 | 64 |

| FINA 201317 | Summer | 18 | 2223 | 1179 | 1044 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 50 |

| Paralympics 20129 | Summer | 14 | 3565 | 2347 | 1218 | 14.2 | 17.6 | 20.1 | 34 |

| Olympics 20125 | Summer | 17 | 10 568 | 5892 | 4676 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 8.6 | 41 |

| Youth Olympics 20128 | Winter | 10 | 1021 | 562 | 459 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 11.0 | 61 |

| IAAF 201118 | Summer | 9 | 1851 | 971 | 880 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 39 |

| Olympics 20107 | Winter | 17 | 2567 | 1522 | 1045 | 7.2 | 5.2 | 8.7 | 63 |

| FIFA 201013 | Winter | 30 | 736 | 736 | − | 12.1 | 12.1 | − | 40 |

| Super Rugby 201015 | Winter | 112 | 259 | 259 | − | 72.2 | 72.2 | − | 31 |

| IAAF 200911 | Summer | 9 | 1979 | 1082 | 897 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 8.4 | 36 |

| FINA 200912 | Summer | 18 | 2599 | 1306 | 1293 | 7.1 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 50 |

| CONFED Cup 200914 | Winter | 14 | 184 | 184 | − | 14.7 | 14.7 | − | 57 |

CONFED Cup, Fédération Internationale de Football Association Confederations Cup; FINA, Federation Internationale de Natation; IAAF, International Athletics Federation; n, number of registered athletes.

These data indicate that in shorter duration (<4 weeks) major international games and tournaments, 6–17% of registered athletes are likely to suffer an illness episode, with an apparently higher incidence proportion (IP—defined as the % athletes presenting with an illness during the games), of tournament or competition illness in female athletes compared with male athletes. Furthermore, the IP of illness appears to be higher in Winter6 compared with Summer Olympic Games5 and data from one study indicate that athletes with disability participating in the Paralympic Games9 appear to have a higher IP of illness than athletes competing in the Olympic Games.5 Finally, the data from one study indicate that during more prolonged competition (4 months)15 there is a higher IP of illness, as might be expected because of the longer duration of the competition.

The organ systems affected by acute illnesses in athletes show a very consistent pattern. Most studies indicate that about 50% of all acute illness in athletes during competitions and tournaments affect the respiratory tract. Other systems commonly affected by illness are the digestive system,5–9 11–15 17 skin and subcutaneous tissues9 15 and the genitourinary system.9 In the majority of studies reporting acute illness in athletes, data are either self-reported symptoms of acute illness or physician-diagnosed using clinical assessment only.5–9 11–15 17 19 20 None of these epidemiological studies used special investigations to confirm the diagnosis of an infective illness. Despite this limitation, clinically diagnosed infections are generally reported as the most common cause of acute illness, with infection being the cause of respiratory tract illness in about 75% of cases. However, it is acknowledged that athletes can develop symptoms (eg, sore throat, sinus congestion, cough) that mimic infections but are actually due to allergy or inflammation from other causes such as inhalation of cold, dry or polluted air.21 22

Performance loss and risks of acute illness in elite athletes

Acute illness presents a significant health burden to the athlete.23 Acute illness can cause reduction in exercise performance, an interruption to training and even result in missing an important international or domestic competition. Acute infective illness can affect a number of organ systems causing a reduction in exercise performance through different mechanisms including muscle wasting,24 impaired motor coordination, a decrease in muscle strength (isotonic and isometric),25 a decrease in maximal oxygen uptake and endurance capacity,24 and alterations in muscle enzyme activity and metabolic function.24 Furthermore, the presence of fever causes a decrease in the body's ability to regulate body temperature and this results in increased fluid losses. Increased fluid loss can decrease both stroke volume and cardiac output, resulting in reduced maximal oxygen consumption.26 It has also been documented that a decrease in exercise performance after full clinical recovery from an upper respiratory tract (URT) illness can last for 2–4 days,27 and recently, data from a prospective cohort study show that runners who start an endurance race with systemic symptoms of an acute illness are 2–3 times less likely to complete the race.28 It has also been reported in elite British athletes from 30 different Olympic sports (24 summer, 6 winter), that illness (most commonly of the respiratory tract) caused 33% of missed training sessions (English Institute of Sport, 2009. Injury and Illness in Great Britain Sport. Olympiad review August 2009 (personal communication; EIS website: http://www.uksport.gov.uk/news/2012/07/25/battle-against-injury-and-illness). Acute infective illness can also increase the risk of serious medical complications and even sudden death during strenuous exercise.24–27 29

There are many intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors that are associated with acute illness in athletes, and it is acknowledged that these risk factors can differ between different types of acute illness in different organ systems. However, there is also some evidence that increased training load, competition load and psychosocial stress together with international travel, as part of a congested sports calendar, may all be risk factors for illness in the elite modern-day professional athlete. Therefore, the IOC convened a consensus meeting from 24 to 27 November 2015 where experts in the field reviewed the scientific evidence for the relationship of load—including a saturated sports calendar—and health outcomes in sport. The expert group searched for, and analysed, current best evidence, aimed to reach consensus, and provided these guidelines for clinical practice and athlete management. In the process, urgent research priorities were also identified.

Terminology and definitions

A first step for the group was to reach consensus on the definition of key terms. This is important as these terms may also serve as a foundation for consistent use in research and clinical practice. The consensus group recognised that the term ‘load’ can have varied definitions. In general, ‘load’ refers to ‘a weight or source of pressure borne by someone or something’.30 Based on this broad term, and the varied usage of the term ‘load’ in the sports medicine and exercise physiology literature, the consensus group applied a broad definition of ‘load’ to describe ‘the sport and non-sport burden (single or multiple physiological, psychological or mechanical stressors) as a stimulus that is applied to a human biological system (including subcellular elements, a single cell, tissues, one or multiple organ systems, or the individual)’. Load can be applied to the individual human biological system over varying time periods (seconds, minutes, hours to days, weeks, months and years) and with varying magnitude (duration, frequency and intensity).

The term ‘external load’ is often used interchangeably with ‘load’, referring to any external stimulus applied to the athlete that is measured independently of their internal characteristics.31 32 Any external load will result in physiological and psychological responses in each individual, following interaction with, and variation in many other factors.33 34 This individual response is referred to as ‘internal load’.

The term ‘illness’ has been defined in the sports medicine literature as ‘a new or recurring illness incurred during competition or training receiving medical attention, regardless of the consequences with respect to absence from competition or training’.5 However, it is recognised that symptomatic illness can be preceded by subclinical immune system alterations that precede symptomatic illness, and not all athletes seek medical attention for early warning symptoms of illness. Therefore, in this consensus document, a broader modified definition of illness was applied as follows: ‘a new or recurring symptomatic illness, or the presence of subclinical immunological precursors of symptomatic illness, that was incurred during competition or training, and either receiving medical attention or was self-reported by athletes, regardless of the consequences with respect to absence from competition or training’. An extensive glossary of other key terms is provided in online supplementary appendix A.

Measures and monitoring

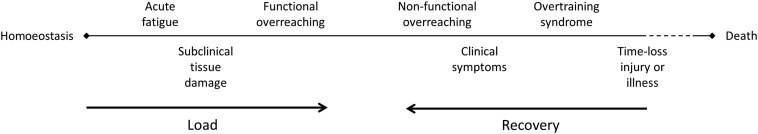

The relationship between athlete's health and loading can be seen in the context of a well-being continuum,35 where load and recovery are mutual counteragents. Sport and non-sport loads impose stress on the athletes, shifting their physical and psychological well-being along a continuum that progresses from homoeostasis to acute fatigue, over-reaching, OTS, subclinical immune changes, clinical symptoms, illness (or injury) and ultimately death. Death is rare in sport, and typically coupled with an underlying disease. For athletes, deterioration (clinically and in performance) along the continuum usually stops at time-loss injury or illness, at which point the athlete is forced to cease further loading. With adequate recovery following a load, the process is reversed, resulting in restored homoeostasis at a higher level of fitness and an improved performance potential (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Well-being continuum.35

Regular monitoring of athletes is fundamental to defining the relationship between load and risk of illness in the care of athletes and in research. This includes accurate measurement and monitoring of the sport and non-sport loads of the athletes, and their performance, how they feel (well-being and clinical symptoms) and any illness.

Monitoring of an athlete's load has many potential advantages, such as explaining changes in performance, increasing the understanding of training responses, revealing fatigue and accompanying needs for recovery, informing the planning and modification of training regimens and competition calendars, and, importantly, ensuring therapeutic levels of load to minimise the risk of maladaptations in the form of non-functional over-reaching (fatigue lasting weeks to months), injury and illness.32 36

Monitoring of external and internal loads

There are many different measures of external and internal loads, and a list or more common measurement tools is listed in online supplementary appendix B. However, the evidence for their validity as markers of adaptation and maladaptation to the load is limited. Currently there is no single marker of an athlete's response to load that consistently predicts acute illness or the OTS.32 37 Load monitoring involves measuring both external and internal loads, where tools to measure the former can be general or sports-specific, and for the latter, objective or subjective.38

Measuring the external load typically involves quantifying the training or competition load of an athlete, such as hours of training, distance run, weight lifted or number of games played; however, other external factors, such as life events, daily hassles or travel may be equally important. The internal load is measured by assessing the internal biological, physiological and psychological response to the external load34 and specific examples include measures such as heart rate (physiological/objective) or rating of perceived exertion (psychological/subjective).

Whereas measuring external load is important in understanding the work completed and capabilities and capacities of the athlete, measuring internal load is critical in determining the appropriate stimulus for optimal biological adaptation.39 40 As individuals will respond differently to any given stimulus, the load required for optimal adaptation may differ significantly from one athlete to another. For example, the ability to maintain a certain running speed or cycling power output for a certain duration may be achieved with a high or low perception of effort or heart rate, depending on numerous interindividual and intraindividual factors, such as fitness and fatigue.32

A recent systematic review on internal load monitoring concluded that subjective measures were more sensitive and consistent than objective measures in determining acute and chronic changes in an athlete's well-being in response to load.38 The following subscales may be useful: non-sport stress, fatigue, physical recovery, general health/well-being, being in shape, vigour/motivation and physical symptoms/illness.35 41–44 These variables offer the coach and other support staff essential data on the athlete's readiness to train or compete, and thus may inform individual adjustments to prescribed training.38

Finally, it has been demonstrated that athletes may perform both longer and/or more intense training,45 or perceive loads as significantly harder31 46 47 than what was intended by the coach or the prescribed training programme. This may pose a considerable problem in the long term, as it may lead to maladaptation to the load. This underscores the importance of monitoring external and internal loads in the individual athlete, rather than as a team average, as it may reveal dissociations between external and internal loads, and helps to ensure that the applied load matches that prescribed by the coach.32

Monitoring of illness and subclinical markers of illness, including immune function

The general principles and guidelines to monitor acute illness patterns in athletes during training and competition have recently been reviewed for aquatic sports48 and athletics.49 In general, in most epidemiological studies, illness monitoring is restricted to athletes presenting with symptoms and clinical signs of acute illness. However, acute infective illness is preceded by a prodromal period that is characterised by pathophysiological changes in various organ systems resulting in the development of non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, myalgia or arthralgia, headache and fever. These early warning clinical symptoms and signs may indicate acute illness, but can also be symptomatic of over-reaching and overtraining.37 There is also good evidence that markers of subclinical (asymptomatic) illness, including changes in the immune system, can occur in response to acute and chronic exercise50–53 and that some of these changes may predict the onset of acute illness.54–60 To date, recommendations for illness monitoring in epidemiological studies have not included the routine measurement of these immune system markers, and further research to determine the sensitivity, specificity and cost-effectiveness of routine testing for these markers as risk factors for illness in athletes is required.

Measures and monitoring of over-reaching (OR) and the OTS

Measures to monitor for over-reaching and overtraining have recently been reviewed in a joint consensus statement published by the European College of Sports Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM).37 There are several criteria for a reliable marker to detect the onset of the OTS in athletes:

A marker should have a high sensitivity (the proportion of people with the condition who have a positive test result) and specificity (the proportion of people without the condition who have a negative test result);

The marker should respond to the training load and ideally be unaffected by other factors (eg, diet and chronobiological rhythms);

Changes in the marker should occur before the establishment of the OTS;

A marker should be distinguishable from other chronic physiological adaptations to training;

The marker should be relatively easy to measure with a quick availability of the result;

The marker should not be too invasive (eg, repeated venous blood samplings are not well accepted) and not too expensive;

The marker should be derived at rest from submaximal or standardised exercise of relatively short duration in order to not interfere with the training process.

However, none of the currently available or suggested markers meet all of these criteria and it is suggested that strategies to monitor for the OTS should include regular recording of training load, using questionnaires, training diaries, psychological screening and direct observational methods.37 If the OTS is suspected in an athlete, a specific diagnostic algorithm, as suggested by the ECSS/ACSM consensus group, can be followed.37 Most recently, it has been suggested that a repeated (4 hours apart) maximal exercise testing protocol can be used to assess athletes for the OTS.61 62 However, there is a lack of definitive monitoring and diagnostic criteria for OR and the OTS.

Load and the risk of illness in athletes

All the members of the consensus group were asked to independently search and review the literature relating load to injury in sports and to contribute to a draft document of the results before the 3-day consensus meeting, organised in Lausanne, Switzerland, in November 2015. This meeting provided a further opportunity for the consensus group to review the literature and to finalise a draft consensus statement. The consensus group further agreed on a post hoc literature search, conducted by the first author of this consensus document after the meeting, to ensure the inclusion of all the relevant scientific information from the different sporting codes. The electronic databases of PubMed, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL and SPORTDiscus were searched from 1 January 1980 to 16 March 2016. The following terms were included in the search, in various combinations: illness, infection, immune, overtraining, sport, exercise, load, workload, recovery, volume, intensity, stress, duration, congestion, distance, mileage and exposure. Only publications in the English language, and studies involving human participants were considered.

After duplicates were eliminated, 796 studies were identified. Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed and assessed for relevance by two researchers (MS and CJVR), using the following inclusion criteria for studies:

Studies involving athletes of all levels (recreational to elite) and sports;

Studies where illness episodes were documented by either a self-report or clinical diagnosis;

Studies where illness episodes were related to training load (internal or external);

Studies where illness episodes were related to competitions, competition calendar, travel load and psychological stressors;

Studies where single (load) or multiple risk factors (load and other risk factors) for illness were studied using univariate or multivariable analyses;

Studies using one of the following research designs: systematic review (with or without a meta-analysis), randomised controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional studies and case–control studies.

In some instances, unpublished data including online manuscripts (not yet published) were included with permission. Final decisions to include publications were based on consensus, and the publications (n=30) that were included in this analysis are summarised in online supplementary appendix C.

Evidence relating absolute training load and the risk of illness

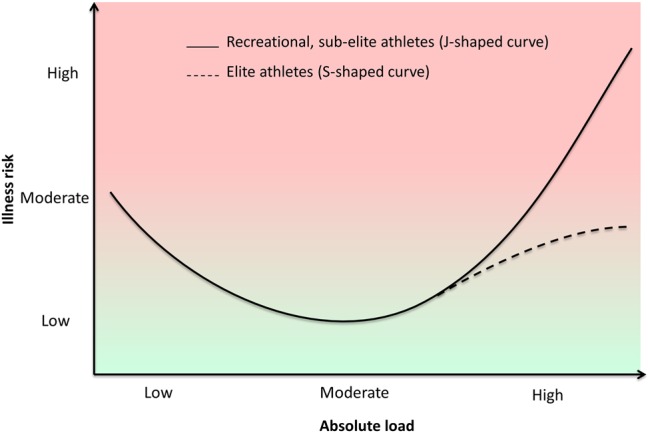

The relationship between absolute training load and risk of illness has been studied for more than three decades. These observations have led to the hypothesis that the relationship between absolute training load and risk of illness is a J-shaped curve,63 with very low or no training being associated with a higher risk of illness compared with moderate training load. Very high training loads are associated with the highest risk of illness in this model. In general, there is good evidence from a number of studies in recreational,55 56 59 64–67 subelite68 69 or national-level athletes,70–72 that higher absolute training loads are associated with an increased risk of illness. Similarly, there is some evidence that low training loads or no training is associated with an increased risk of illness compared with a moderate training load.73 74

However, recently, it has been suggested that the J-shaped relationship between absolute training load and illness is not necessarily applicable to high-level elite international athletes.75 Data from a number of recent studies show that high absolute training loads in international-level70 76 77 and medal-winning athletes3 are associated with a lower risk of illness compared with the subelite or national-level athletes. The precise reasons for this observation are not clear, but one explanation may be that it is a result of ‘self-selection’ and that to become a high-level international elite athlete one has to possess an incredible physique, including an immune system able to withstand infections even during severe physiological and psychological stress.75

In summary, there is evidence that high absolute training loads are associated with an increased risk of illness in recreational and subelite athletes (J-shaped curve). However, there is also evidence that this relationship does not necessarily apply to elite athletes on the highest level, where high training loads are not associated with an increased risk of illness (S-shaped curve)75 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The relationship between load and risk of illness in recreational and subelite athletes (J-shaped curve) versus elite athletes (S-shaped curve).63 75

Evidence relating changes in training load and the risk of illness

The relationship between risk of illness and changes (spikes or drops in intensity, duration or frequency) in training load has only been explored in a few studies. In one of the first studies where the daily training load and illness episodes were monitored in a group of recreational runners over 12 months, an increase in the volume of training was associated with an increased risk of illness.67 Similarly, in subsequent studies, increases in training volume were associated with increased risk of illness in elite junior tennis players,55 subelite basketball players68 and elite swimmers.70 71 Furthermore, in a prospective study in the elite rugby union players, periods of increased intensity of training preceded the development of URT illness symptoms,78 while in another study among elite swimmers, a 10% increase in training load was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of URT illness symptoms.70 In elite cross-country skiers, training monotony, reflecting little change in training load, was associated with a lower risk of illness,3 but this was not confirmed in another 29-week prospective study in 32 rugby league players, where training monotony, together with overall increased internal load and load strain were all associated with an increased risk for self-reported illness.79

In summary, there is some evidence that changes in external (increased volume and intensity of training) and internal training loads are associated with an increased risk of illness. However, given the current data it is not yet possible to quantify which amount of training load increase is related to increased risk of a specific illness, or in a specific sport. Training monotony as a risk factor for illness has only been studied recently in two populations, with varied results, and this requires further investigation.

Evidence relating sporting competition and risk of illness

As well as absolute and relative changes in training load, participating in single or multiple competitions (tournaments) also increases athletes’ risk of illness. Competition load can refer to a single event (race, game) or multiple events over a period of time in different venues and of different durations. The earliest studies relating competition load and risk of illness were conducted among recreational runners participating in a single prolonged and strenuous ultramarathon event. These showed that URT illness symptoms were more frequent in the 1–2 weeks after the race compared with non-running controls.66 80–82 Postrace URT illness episodes were more frequent in faster runners,66 80 81 and in runners with a history of prerace URT illness symptoms.83 However, in shorter races (5, 10 and 21 km), postrace URT illness episodes were not related to prerace URT illness symptoms.84 These early data indicated that prerace URT illness symptoms, and increased race intensity and duration were associated with an increased risk of postrace URT illness symptoms.

Competition load and risk of illness has only been documented in a few sports other than distance running. In elite tennis players, increased matches per week were associated with increased risk of URT illness symptoms,55 while more frequent training and competition periods were associated with increased URT illness symptoms in American college football players.56 Recently, a number of prospective studies confirmed that both the precompetition and the competition period are associated with an increased risk of illness. In one study with a five-season follow-up of elite track and field athletes, 50% of all illness episodes occurred in the 2 months prior to major competitions.23 In another study, elite cross-country skiers participating in an 11-day ski tour had a higher incidence of illness compared with skiers not participating in the tournament.85 Finally, competition was an independent risk factor for illness (odds ratio for illness=2.9) in a group of elite cross-country skiers that were followed over a 7–8 years period.3

In summary, the current data indicate that participation in competitions (single or multiple) is associated with an increased risk of illness, but there are too few data to quantify that risk and this requires further investigation. The factors responsible for this increased risk as a result of competition are likely to be multifactorial and also need to be explored in future studies.

Evidence relating international travel and risk of illness in athletes

The modern-day elite athlete typically competes in an increasing number of competitions and tournaments on the international circuit. This necessitates more frequent international travel for competition purposes, and for training camps. Travel medicine is a branch of medicine studying the effects of travel and risk of illness. Published data relating illness and international travel in non-athletes are limited because of a number of factors including selection bias (surveys from individuals who seek assistance at travel clinics), information bias (self-reported data on illness), recall bias (data obtained weeks after return from travel), poor response rates, failure to control for confounders86 and failure to document exposure (person days or weeks).87 Prospective cohort studies are particularly important to determine the incidence and risk factors associated with illness as a result of travel.86 88 89

The relationship between risk of illness in athletes and international travel has been investigated in very few studies. In the first study to determine the risk of illness in athletes during international travel, travelling across more than four time zones was associated with a 2–3 times increased risk of illness in elite rugby union players competing in a 16-week tournament.4 Recently, international travel was also shown to be associated with significantly more URT illness symptoms in professional rugby players travelling across 11 time zones,90 while international travel was an independent risk factor for illness in another prospective study among elite cross-country skiers.3 Although the precise mechanisms for these observations have not been investigated, monitoring air travel (eg, frequency, duration, recovery time from travel across multiple time zones and risk of illness associated with the travel destination) of elite athletes should be encouraged as an important consideration to reduce the risk of illness.

Evidence relating psychological load and risk of illness in athletes

There is evidence in the literature that the risk of illness is increased when an athlete is exposed to other non-exercise stressors to the immune system, including lack of sleep or severe psychosocial stress.91–94 In one study in young elite soccer players,95 psychosocial stress and recovery were related to the occurrence of illness, supporting the findings of other studies reporting that illness is also related to a disturbed balance between psychological stress and recovery.36 93 96

Methodological considerations

It is important to note that the quality of the data on the influence of training and competition loads and risk of illness is compromised by clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Some of the more specific methodological considerations include the following:

Most studies have been conducted in athletes participating in individual endurance sports (cross-country skiing, swimming, biathlon, distance running, cycling, orienteering) with only a few studies in team sports (Australian football, tennis, football, rugby union, rugby league, basketball) and mixed sport types (university sports).

Studies have been conducted across all sporting levels ranging from recreational to elite sports.

Studies have included athletes from all age groups and from both sexes.

In the majority of studies, illness was documented as self-reported symptoms, through the use of questionnaires.

In all studies, external training load was measured, while internal load was only measured in some studies and changes in load were documented in very few studies.

Multiple risk factors for illness were measured in most studies, but in only a few studies were these risk factors included in multiple risk factor modelling to determine the independent risk factor for illness.

Practical clinical guidelines for load management to reduce the risk of illness in athletes

The prevention of illness is a key component in athletes’ health management. Illness prevention strategies are important to optimise uninterrupted training, and to reduce the risk of illness that can prevent participation in important competitions. Furthermore, illness prevention may reduce the risk of medical complications during exercise. In one observational study, an illness prevention programme in the Norwegian Olympic Winter Games (OWG) team reduced the illness rate from 17.3% of athletes competing in the Turin OWG, to 5.1% of athletes competing in the Vancouver OWG. The authors suggested that the reduced incidence of illness contributed to the improved performance and overall results of the team at the Vancouver OWG.97

There is no single method that completely eliminates the risk of illness in athletes, but there are several effective behavioural, nutritional and training strategies that can lower exposure to pathogens and limit the extent of exercise-induced immunodepression, thereby reducing the risk of illness.98 Therefore, it is recommended that medical staff, who are responsible for individual athletes and teams, develop, implement and monitor illness prevention strategies to reduce the risk of illness.97 99 100 The general guidelines for illness prevention in athletes could include adopting behavioural, lifestyle and medical strategies to limit the transmission of infections, nutritional strategies to maintain robust immunity in athletes, measuring, monitoring and managing training and competition load, and measuring and monitoring athletes to detect early signs and symptoms of illness, over-reaching and overtraining. These general guidelines by the group, through consensus, are summarised in box 1.

Box 1. General guidelines for illness prevention in athletes.

-

Behavioural, lifestyle and medical strategies

A variety of behavioural, lifestyle and medical intervention strategies have been advocated to reduce the risk of illness in the athlete. These include advice to athletes, measures taken by medical staff and the athlete support team.

Athletes are advised to:

Minimise contact with infected people, young children, animals and contagious objects;

Avoid crowded areas and shaking hands and minimise contact with people outside the team and support staff;

Keep at distance to people who are coughing, sneezing or have a ‘runny nose’, and when appropriate wear (or ask them to wear) a disposable mask;

Cough or sneeze on to the elbow and not on the hands—always clean the hands and nose after sneezing or coughing;

Wash hands regularly and effectively with soap and water, especially before meals, and after direct contact with potentially contagious people, animals, blood, secretions, public places and bathrooms;

Use disposable paper towels and limit hand to mouth/nose contact when suffering from upper respiratory symptoms or gastrointestinal illness (putting hands to eyes and nose is a major route of viral self-inoculation);

Carry insect repellent, antimicrobial foam/cream or alcohol-based hand washing gel with them;

Not to share drinking bottles, cups, cutlery, towels, etc, with other people;

Choose beverages from sealed bottles, avoid raw vegetables and undercooked meat, wash and peel fruit before eating, while competing or training abroad;

Wear enough covered clothing (covering the arms and legs) during training sessions when travelling in tropical areas, particularly at dusk and dawn;

Wear open footwear when using public showers, swimming pools and locker rooms in order to avoid dermatological diseases;

Adopt strategies that facilitate good quality sleep such as strategic napping during the day and correct sleep hygiene practices at night;

Avoid excessive drinking and binge drinking of alcohol as this impairs immune function for several hours, particularly after strenuous training or competition;

Practice the principles of safe sex and use condoms.

Medical staff taking care of athletes is advised to consider the following:

Develop, implement and monitor illness prevention guidelines for athletes and medical and administrative support staff;

Screening for airway inflammation disturbances (asthma, allergy and other inflammatory airway conditions);

Identify the high-risk athletes and take full preventative precautions during high-risk training or competition periods;

Arrange for single room accommodation during tournaments for athletes with heavy competition load or known susceptibility to respiratory tract infections, or high performance priority athletes;

Consider protecting the airways of athletes from being directly exposed to very cold (<0°C) and dry air during strenuous exercise by using a facial mask;

Adopt measures to reduce the risk of illness associated with international travel;

Update athletes vaccines needed at home and for foreign travel and take into consideration that influenza vaccines take 5–7 weeks to take effect, intramuscular vaccines may have a few small side effects, vaccinations are performed preferably out of season and avoid vaccinating just before competitions or if symptoms of illness are present;

Update administrative and support staff vaccines needed at home and for foreign travel;

Consider zinc lozenges (>75 mg zinc/day; high ionic zinc content) at the onset of upper respiratory symptoms, as there is some evidence that the number of days with illness symptoms can be reduced.

The athlete support team can consider adopting nutritional measures to maintain robust immunity in athletes, including the following:

Introduce personalised nutrition programmes to avoid deficiencies of essential micronutrients;

Encourage athletes to ingest carbohydrate during and after exercise and to ingest both carbohydrate and protein after exercise;

Measure and monitor the vitamin D status of athletes and supplement if required;

Consider advising athletes to ingest probiotic such as Lactobacillus probiotics on a daily basis;

Consider advising athletes on the regular consumption of fruits and plants, polyphenol supplements (eg, quercetin), or foodstuffs (eg, non-alcoholic beer and green tea) that may reduce risk of illness.

-

Training and competition load management

There is evidence that poor load management with ensuing maladaptation can be a significant risk factor for acute illness and overtraining. However, data are limited to a few select sports and athlete populations, and this, combined with the unique nature of different sports, make it difficult to provide sport-specific guidelines for load management. However, the following general recommendations can be made:

Very high loads can have either positive or negative influences on risk of illness in athletes, with the athlete's level of competition (elite), load history (chronic load) and intrinsic risk factor profile being important;

Athletes should have a detailed individualised training and competition plan, including postevent recovery measures (encompassing nutrition and hydration, sleep, and psychological recovery);

The training load is monitored using measurements of external and internal load;

- Training load is managed by adopting the following principles:

- Changes in training load should be individualised as there are large intraindividual and interindividual variances in the timeframe of response and adaptation to load;

- Changes in training load should be in small increments, with data (from the injury literature) indicating that weekly increments should be <10%;

The competition load is monitored and managed;

Variation in an athlete's psychological stressors should guide the prescription of training and/or competition loads;

It is recommended that coaches and support staff schedule adequate recovery, particularly after intensive training periods, competitions and travel, including nutrition and hydration, sleep and rest, active rest, relaxation strategies and emotional support;

Sports governing bodies have the responsibility to consider the competition load, and hence the health of the athletes when planning their event calendars. This requires increased coordination between single-sport and multisport event organisers, and the development of a comprehensive calendar of all international sports events.

-

Psychological load management

Psychological load (stressors) such as negative life event stress and daily hassles can significantly increase the risk of illness in athletes. Clinical practical recommendations centre on reducing state-level stressors and educating athletes, coaches and support staff in proactive stress management, and comprise the following:43

Developing resilience strategies that help athletes understand the relationship between personal traits, negative life events, thoughts, emotions and physiological states, which, in turn, may help them minimise the impact of negative life events and the subsequent risk of illness;

Educating athletes in stress management techniques, confidence building and goal setting, optimally under supervision of a sport psychologist, to help minimise the effects of stress and reduce the likelihood of illness;

Reducing training and/or competition loads and intensities to mitigate risk of illness for athletes who appear unfocused as a consequence of negative life events or ongoing daily hassles;

Implementing periodical stress assessments (eg, hassle and uplift scale,101 LESCA102) to inform adjustment of athletes' training and/or competition loads. An athlete who reports high levels of daily hassle or stress could likely benefit from reducing the training load during a specified time period to prevent potential fatigue, illness or burnout.43

-

Measuring and monitoring for early signs and symptoms of illness, over-reaching and overtraining

The use of sensitive measures to monitor an athlete's health can lead to early detection of symptoms and signs of illness, early diagnosis and appropriate intervention. Athletes' innate tendency to continue to train and compete despite the existence of physical complaints or functional limitations, particularly at the elite level, highlight the pressing need to use appropriate illness monitoring tools. It is recommended that:

Ongoing illness (and injury) surveillance systems should be implemented in all sports;

Athletes be monitored, using sensitive tools, for subclinical signs of illness such as non-specific symptoms and signs, or selected special investigations;

Athletes be monitored for overt symptoms and signs of illness;

Athletes be monitored for early symptoms and signs of over-reaching or overtraining;

Illness monitoring should be ongoing, and long enough to detect early indicators of illness particularly during alterations in training load, travel and competitions.

Suggested areas for research to prevent illness as a result of excessive training or competition load

In general, there is a paucity of research data on the risk of illness as a result of a congested sports calendar, or an increased training or competition load. The consensus group identified that there is a need to conduct large-scale prospective cohort studies to identify the risk factors associated with illness in athletes, including the role of training and competition load as well as international travel. Once the risk factors have been identified, intervention studies, that are designed to reduce the risk of illness, can be planned and implemented. Follow-up studies to determine the effects of intervention strategies can then be planned and implemented, recognising that these studies may be difficult to conduct in elite, professional athletes. We suggest the following specific areas for future research:

Develop consistent systems to measure load and monitor the athletes;

Determine the impact of illness on individual and team sports performance;

Explore the dose–response relationship of training and competition load on risk of illness, and quantifying the risk;

Explore the dose–response relationship of recovery time on risk of illness;

Identify potential cut-off and maximum number of competitions in athletes (per age groups, and in professional athletes in different Olympic sports);

Examine, and quantify the effect of illness prevention strategies including preseason screening, management of training and competition load, early detection of subclinical illness, recovery modalities and the use of nutritional interventions;

Examine, and quantify the association (including mechanisms) between the risk of illness and international travel including jet lag, and sleep deprivation;

Examine, and quantify the effect of illness prevention strategies to minimise the risk of illness during international travel;

Determine the mechanisms by which intensified training and competition affect health parameters including immunological, oxidative stress-related and cardiovascular parameters;

Explore the individual responses of athletes to changes in training and competition load, including genetic factors.

Summary

Data on the relationship between training and competition load and the risk of illness are limited to a few select sports and athlete populations. High loads can have either positive or negative influences on risk of illness in athletes. High absolute training loads are associated with an increased risk of illness in recreational and subelite athletes (J-shaped curve). There is some evidence that this may not be the case in high-level elite athletes (S-shaped curve). Increased external (volume and intensity of training) and internal training loads are associated with an increased risk of illness, while training monotony as a risk factor for illness has only been studied in two populations, with varied results, requiring further investigation. At present, there is not enough data to quantify the risk of illness in response to absolute load or changes in load, and this requires further investigation. Regular athlete monitoring is fundamental to ensure appropriate external and internal training loads to maximise performance and minimise the risk of illness. Emerging evidence suggests that frequent and prolonged air travel across multiple time zones is associated with risk of illness in athletes but the precise mechanisms for these observations are unknown. It is prudent for sports governing bodies, concerned with athletes’ health to consider the overall competition load when planning event calendars. More research is needed on the impact of competition calendar congestion and rapid changes in training load on risk of illness in multiple sports, as well as on the interaction with other physiological, psychological, environmental and genetic risk factors.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Torbjørn Soligard at @TSoligard, Juan Manuel Alonso at @DrJuanMAlonso, Benjamin Clarsen at @benclarsen and Hendrik Dijkstra at @DrPaulDijkstra

Contributors: MS and TS made substantial contributions to overall and detailed conception, planning, drafting and critically revising the paper. J-MA, RBa, BC, HPD, TJG, MG, MH, MRH, CJVR, RM, JWO, BMP and MR made substantial contributions to drafting and critically revising the paper. LE and RBu made substantial contributions to overall conception and planning of the paper.

Funding: The consensus meeting was funded by the IOC.

Competing interests: TS works as Scientific Manager in the Medical and Scientific Department of the IOC. JWO is Chief Medical Officer for Cricket Australia and was the Chief Medical Officer of the International Cricket Council Cricket World Cup 2015. BMP is Chief Medical Officer of the Royal Dutch Lawn Tennis Association and member of the International Tennis Federation (ITF) Sport Science and Medicine Commission. She is Editor of the British Journal of Sports Medicine. LE is Head of Scientific Activities in the Medical and Scientific Department of the IOC, and Editor of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, et al. Position statement. Part one: immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev 2011;17:6–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleeson M, Pyne DB. Respiratory inflammation and infections in high-performance athletes. Immunol Cell Biol 2016;94:124–31. 10.1038/icb.2015.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svendsen IS, Taylor IM, Tonnesen E, et al. Training- and competition-related risk factors for respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections in elite cross-country skiers. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:809–15. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwellnus MP, Derman WE, Jordaan E, et al. Elite athletes travelling to international destinations >5 time zone differences from their home country have a 2–3-fold increased risk of illness. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:816–21. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:407–14. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soligard T, Steffen K, Palmer-Green D, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses in the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:441–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engebretsen L, Steffen K, Alonso JM, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the Winter Olympic Games 2010. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:772–80. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.076992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruedl G, Schobersberger W, Pocecco E, et al. Sport injuries and illnesses during the first Winter Youth Olympic Games 2012 in Innsbruck, Austria. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:1030–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derman W, Schwellnus M, Jordaan E, et al. Illness and injury in athletes during the competition period at the London 2012 Paralympic Games: development and implementation of a web-based surveillance system (WEB-IISS) for team medical staff. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:420–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derman W, Schwellnus MP, Jordaan E, et al. The incidence and patterns of illness at the Sochi 2014 Winter Paralympic Games: a prospective cohort study of 6564 athlete days. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 9 May 2016 doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096215 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso JM, Tscholl PM, Engebretsen L, et al. Occurrence of injuries and illnesses during the 2009 IAAF World Athletics Championships. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1100–5. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.078030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mountjoy M, Junge A, Alonso JM, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses in the 2009 FINA World Championships (Aquatics). Br J Sports Med 2010;44:522–7. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.071720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dvorak J, Junge A, Derman W, et al. Injuries and illnesses of football players during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:626–30. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theron N, Schwellnus M, Derman W, et al. Illness and injuries in elite football players—a prospective cohort study during the FIFA Confederations Cup 2009. Clin J Sport Med 2013;23:379–83. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31828b0a10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwellnus M, Derman W, Page T, et al. Illness during the 2010 Super 14 Rugby Union tournament—a prospective study involving 22 676 player days. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:499–504. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prien A, Mountjoy M, Miller J, et al. Injury and illness in aquatic sport: how high is the risk? A comparison of results from three FINA World Championships. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 16 June 2016. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096075 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mountjoy M, Junge A, Benjamen S, et al. Competing with injuries: injuries prior to and during the 15th FINA World Championships 2013 (aquatics). Br J Sports Med 2015;49:37–43. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso JM, Edouard P, Fischetto G, et al. Determination of future prevention strategies in elite track and field: analysis of Daegu 2011 IAAF Championships injuries and illnesses surveillance. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:505–14. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarsen B, Rønsen O, Myklebust G, et al. The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:754–60. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjørneboe J, Kristenson K, Waldén M, et al. Role of illness in male professional football: not a major contributor to time loss. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:699–702. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwellnus MP, Lichaba M, Derman EW. Respiratory tract symptoms in endurance athletes—a review of causes and consequences. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;23:52–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bermon S. Airway inflammation and upper respiratory tract infection in athletes: is there a link? Exerc Immunol Rev 2007;13:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raysmith BP, Drew MK. Performance success or failure is influenced by weeks lost to injury and illness in elite Australian Track and Field athletes: a 5-year prospective study. J Sci Med Sport 2016. Jan 7. pii: S1440-2440(15)00764-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.515. [Epub ahead of print] 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friman G, Wesslén L. Special feature for the Olympics: effects of exercise on the immune system: infections and exercise in high-performance athletes. Immunol Cell Biol 2000;78:510–22. 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2000.t01-12-.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidner TG, Sevier TL. Sport, exercise, and the common cold. J Athl Train 1996;31:154–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exercise and febrile illnesses. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12:885–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwellnus MP, Jeans A, Motaung S, et al. Exercise and infections. In: Schwellnus MP, ed. The Olympic textbook of medicine in sport. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008:344–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Tonder A, Schwellnus M, Swanevelder S, et al. A prospective cohort study of 7031 distance runners shows that 1 in 13 report systemic symptoms of an acute illness in the 7-day period before a race, increasing their risk of not finishing the race 1.9 times for those runners who started the race: SAFER study IV. Br J Sport Med 2016;50:939–45. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng GS, Hsieh CY, Hsu CT, et al. Myopericarditis and exertional rhabdomyolysis following an influenza A (H3N2) infection. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:283 10.1186/1471-2334-13-283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oxford Dictionaries. ’Load‘. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/load (accessed 24 May 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace LK, Slattery KM, Coutts AJ. The ecological validity and application of the session-RPE method for quantifying training loads in swimming. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:33–8. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181874512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halson SL. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med 2014;44(Suppl 2):S139–47. 10.1007/s40279-014-0253-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Impellizzeri FM, Rampinini E, Marcora SM. Physiological assessment of aerobic training in soccer. J Sports Sci 2005;23:583–92. 10.1080/02640410400021278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borresen J, Lambert MI. The quantification of training load, the training response and the effect on performance. Sports Med 2009;39:779–95. 10.2165/11317780-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fry RW, Morton AR, Keast D. Overtraining in athletes. An update. Sports Med 1991;12:32–65. 10.2165/00007256-199112010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster C. Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:1164–8. 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45:186–205. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saw AE, Main LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring the athlete training response: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2015;50:281–91. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth FW, Thomason DB. Molecular and cellular adaptation of muscle in response to exercise: perspectives of various models. Physiol Rev 1991;71: 541–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viru A, Viru M. Nature of training effects. In: Garrett WE, Kirkendall DT, eds. Exercise and sport science. 1st edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000:67–96. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hooper SL, Mackinnon LT. Monitoring overtraining in athletes. Recommendations. Sports Med 1995;20:321–7. 10.2165/00007256-199520050-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kentta G, Hassmen P. Overtraining and recovery. A conceptual model. Sports Med 1998;26:1–16. 10.2165/00007256-199826010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivarsson A, Johnson U, Podlog L. Psychological predictors of injury occurrence: a prospective investigation of professional Swedish soccer players. J Sport Rehabil 2013;22:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuipers H. Training and overtraining: an introduction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:1137–9. 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res 2001;15:109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brink MS, Frencken WGP, Jordet G, et al. Coaches’ and players’ perceptions of training dose: not a perfect match. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2014;9:497–502. 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy AP, Duffield R, Kellett A, et al. Comparison of athlete-coach perceptions of internal and external load markers for elite junior tennis training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2014;9:751–6. 10.1123/ijspp2013-0364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mountjoy M, Junge A, Alonso JM, et al. Consensus statement on the methodology of injury and illness surveillance in FINA (aquatic sports). Br J Sports Med 2016;50:590–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timpka T, Alonso JM, Jacobsson J, et al. Injury and illness definitions and data collection procedures for use in epidemiological studies in Athletics (track and field): consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:483–90. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simpson RJ, Kunz H, Agha N, et al. Exercise and the regulation of immune functions. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2015;135:355–80. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh NP, Oliver SJ. Exercise, immune function and respiratory infection: an update on the influence of training and environmental stress. Immunol Cell Biol 2015;94:132–9. 10.1038/icb.2015.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown WM, Davison GW, McClean CM, et al. A systematic review of the acute effects of exercise on immune and inflammatory indices in untrained adults. Sports Med Open 2015;1:35 10.1186/s40798-015-0032-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gleeson M. Immunological aspects of sport nutrition. Immunol Cell Biol 2016;94:117–23. 10.1038/icb.2015.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gleeson M, McDonald WA, Pyne DB, et al. Salivary IgA levels and infection risk in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31:67–73. 10.1097/00005768-199901000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Novas AM, Rowbottom DG, Jenkins DG. Tennis, incidence of URTI and salivary IgA. Int J Sports Med 2003;24:223–9. 10.1055/s-2003-39096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fahlman MM, Engels HJ. Mucosal IgA and URTI in American college football players: a year longitudinal study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:374–80. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000155432.67020.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Dumke CL, et al. Relationship between salivary IgA secretion and upper respiratory tract infection following a 160-km race. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2006;46:158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neville V, Gleeson M, Folland JP. Salivary IgA as a risk factor for upper respiratory infections in elite professional athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:1228–36. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816be9c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gleeson M, Bishop N, Oliveira M, et al. Respiratory infection risk in athletes: association with antigen-stimulated IL-10 production and salivary IgA secretion. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012;22:410–17. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanstock HG, Walsh NP, Edwards JP, et al. Tear fluid SIgA as a noninvasive biomarker of mucosal immunity and common cold risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48:569–77. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meeusen R, Piacentini MF, Busschaert B, et al. Hormonal responses in athletes: the use of a two bout exercise protocol to detect subtle differences in (over)training status. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004;91:140–6. 10.1007/s00421-003-0940-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meeusen R, Nederhof E, Buyse L, et al. Diagnosing overtraining in athletes using the two-bout exercise protocol. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:642–8. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.049981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shephard RJ, Shek PN. Exercise, immunity, and susceptibility to infection: a j-shaped relationship? Phys Sportsmed 1999;27:47–71. 10.3810/psm.1999.06.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gleeson M, Bishop N, Oliveira M, et al. Influence of training load on upper respiratory tract infection incidence and antigen-stimulated cytokine production. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013;23:451–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novas A, Rowbottom D, Jenkins D. Total daily energy expenditure and incidence of upper respiratory tract infection symptoms in young females. Int J Sports Med 2002;23:465–70. 10.1055/s-2002-35075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peters EM, Goetzsche JM, Grobbelaar B, et al. Vitamin C supplementation reduces the incidence of postrace symptoms of upper-respiratory-tract infection in ultramarathon runners. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:170–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heath GW, Ford ES, Craven TE, et al. Exercise and the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991;23:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moreira A, Arsati F, Lima-Arsati YB. Monitoring stress tolerance and occurrences of upper respiratory illness in basketball players by means of psychometric tools and salivary biomarkers. Stress Health 2011;27:e166–72. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matthews A, Pyne D, Saunders P, et al. A self-reported questionnaire for quantifying illness symptoms in elite athletes. Open Access J Sports Med 2010;1:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hellard P, Avalos M, Guimaraes F, et al. Training-related risk of common illnesses in elite swimmers over a 4-year period. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:698–707. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rama L, Teixeira AM, Matos A, et al. Changes in natural killer cell subpopulations over a winter training season in elite swimmers. Eur J Appl Physiol 2013;113:859–68. 10.1007/s00421-012-2490-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spence L, Brown WJ, Pyne DB, et al. Incidence, etiology, and symptomatology of upper respiratory illness in elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:577–86. 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802e851a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matthews CE, Ockene IS, Freedson PS, et al. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and risk of upper-respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1242–8. 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Austin MD, et al. Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:987–92. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malm C. Susceptibility to infections in elite athletes: the S-curve. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:4–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Veugelers KR, Young WB, Fahrner B, et al. Different methods of training load quantification and their relationship to injury and illness in elite Australian football. J Sci Med Sport 2016;19:24–8. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mårtensson S, Nordebo K, Malm C. High training volumes are associated with a low number of self-reported sick days in elite endurance athletes. J Sports Sci Med 2014;13:929–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cunniffe B, Griffiths H, Proctor W, et al. Mucosal immunity and illness incidence in elite rugby union players across a season. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:388–97. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ef9d6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thornton HR, Delaney JA, Duthie GM, et al. Predicting self-reported illness for professional team-sport athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2016;11:543–50. 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters EM, Bateman ED. Ultramarathon running and upper respiratory tract infections. An epidemiological survey. S Afr Med J 1983;64:582–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters EM. Altitude fails to increase susceptibility of ultramarathon runners to post-race upper respiratory tract infections. S Afr J Sports Med 1990;5:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nieman DC, Johanssen LM, Lee JW, et al. Infectious episodes in runners before and after the Los Angeles Marathon. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1990;30:316–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ekblom B, Ekblom O, Malm C. Infectious episodes before and after a marathon race. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:287–93. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nieman DC, Johanssen LM, Lee JW. Infectious episodes in runners before and after a roadrace. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1989;29:289–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Svendsen IS, Gleeson M, Haugen TA, et al. Effect of an intense period of competition on race performance and self-reported illness in elite cross-country skiers. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015;25:846–53. 10.1111/sms.12452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel D. Occupational travel. Occup Med (Lond) 2011;61:6–18. 10.1093/occmed/kqq163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Newman-Klee C, D'Acremont V, Newman CJ, et al. Incidence and types of illness when traveling to the tropics: a prospective controlled study of children and their parents. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007;77:764–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Talbot EA, Chen LH, Sanford C, et al. Travel medicine research priorities: establishing an evidence base. J Travel Med 2010;17:410–15. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leder K, Wilson ME, Freedman DO, et al. A comparative analysis of methodological approaches used for estimating risk in travel medicine. J Travel Med 2008;15:263–72. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fowler PM, Duffield R, Lu D, et al. Effects of long-haul transmeridian travel on subjective jet-lag and self-reported sleep and upper respiratory symptoms in professional Rugby League players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2016. Jan 18. 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0542 [Epub ahead of print] 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nieman DC, Pedersen BK. Exercise and immune function. Recent developments. Sports Med 1999;27:73–80. 10.2165/00007256-199927020-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nieman DC. Special feature for the Olympics: effects of exercise on the immune system: exercise effects on systemic immunity. Immunol Cell Biol 2000;78:496–501. 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2000.t01-5-.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Main LC, Landers GJ, Grove JR, et al. Training patterns and negative health outcomes in triathlon: longitudinal observations across a full competitive season. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2010;50:475–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kellmann M. Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20(Suppl 2):95–102. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brink MS, Visscher C, Coutts AJ, et al. Changes in perceived stress and recovery in overreached young elite soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012;22:285–92. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Putlur P, Foster C, Miskowski JA, et al. Alteration of immune function in women collegiate soccer players and college students. J Sports Sci Med 2004;3:234–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hanstad DV, Ronsen O, Andersen SS, et al. Fit for the fight? Illnesses in the Norwegian team in the Vancouver Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:571–5. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.081364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Pyne DB, et al. Position statement. Part two: maintaining immune health. Exerc Immunol Rev 2011;17:64–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dijkstra HP, Pollock N, Chakraverty R, et al. Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:523–31. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Palmer-Green D, Elliott N. Sports injury and illness epidemiology: Great Britain Olympic Team (TeamGB) surveillance during the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:25–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:486–95. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Petrie TA. Psychosocial antecedents of athletic injury: the effects of life stress and social support on female collegiate gymnasts. Behav Med 1992;18:127–38. 10.1080/08964289.1992.9936963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]