Abstract

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the master circadian oscillator encoding time-of-day information. SCN timekeeping is sustained by a cell-autonomous transcriptional–translational feedback loop, whereby expression of the Period and Cryptochrome genes is negatively regulated by their protein products. This loop in turn drives circadian oscillations in gene expression that direct SCN electrical activity and thence behavior. The robustness of SCN timekeeping is further enhanced by interneuronal, circuit-level coupling. The aim of this study was to combine pharmacological and genetic manipulations to push the SCN clockwork toward its limits and, by doing so, probe cell-autonomous and emergent, circuit-level properties. Circadian oscillation of mouse SCN organotypic slice cultures was monitored as PER2::LUC bioluminescence. SCN of three genetic backgrounds—wild-type, short-period CK1εTau/Tau mutant, and long-period Fbxl3Afh/Afh mutant—all responded reversibly to pharmacological manipulation with period-altering compounds: picrotoxin, PF-670462 (4-[1-Cyclohexyl-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl]-2-pyrimidinamine dihydrochloride), and KNK437 (N-Formyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-benzylidine-gamma-butyrolactam). This revealed a remarkably wide operating range of sustained periods extending across 25 h, from ≤17 h to >42 h. Moreover, this range was maintained at network and single-cell levels. Development of a new technique for formal analysis of circadian waveform, first derivative analysis (FDA), revealed internal phase patterning to the circadian oscillation at these extreme periods and differential phase sensitivity of the SCN to genetic and pharmacological manipulations. For example, FDA of the CK1εTau/Tau mutant SCN treated with the CK1ε-specific inhibitor PF-4800567 (3-[(3-Chlorophenoxy)methyl]-1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine hydrochloride) revealed that period acceleration in the mutant is due to inappropriately phased activity of the CK1ε isoform. In conclusion, extreme period manipulation reveals unprecedented elasticity and temporal structure of the SCN circadian oscillation.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The master circadian clock of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) encodes time-of-day information that allows mammals to predict and thereby adapt to daily environmental cycles. Using combined genetic and pharmacological interventions, we assessed the temporal elasticity of the SCN network. Despite having evolved to generate a 24 h circadian period, we show that the molecular clock is surprisingly elastic, able to reversibly sustain coherent periods between ≤17 and >42 h at the levels of individual cells and the overall circuit. Using quantitative techniques to analyze these extreme periodicities, we reveal that the oscillator progresses as a sequence of distinct stages. These findings reveal new properties of how the SCN functions as a network and should inform biological and mathematical analyses of circadian timekeeping.

Keywords: bioluminescence, casein kinase, FBXL3, organotypic slice, period, picrotoxin

Introduction

The paired suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCNs) are the principal circadian clock of mammals. Each consists of a small network of ∼10,000 neurons, and together they coordinate daily rhythms of activity and physiology that adapt individuals to the demands of the day/night cycle. In the absence of temporal cues, these rhythms free run with a circa (ca.) 24 h period, emphasizing the stability of the circadian system. The molecular clockwork of the SCN (and its subordinate clocks distributed across the body) consists of a transcriptional–translational feedback loop in which the Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry) genes are negatively regulated by their protein products (Hastings et al., 2014). The period of the oscillation is determined, inter alia, by rates of expression and degradation of PER and CRY proteins (Maywood et al., 2011b), while ultimate coordination of behavior and physiology is mediated by the circadian cycle of spontaneous electrical firing by SCN neurons, regulated by the core molecular loop (Colwell, 2011).

The molecular oscillation can be monitored in real time in organotypic SCN slices using genetically encoded reporters, e.g., the PER2-luciferase fusion protein (PER2::LUC; Yoo et al., 2004). Remarkably, SCN tissue explants maintain free-running circadian rhythms more or less indefinitely in suitable culture conditions. This stability and robustness are conferred by tight network communication, mediated through electrical activity and neuropeptidergic signaling (Yamaguchi et al., 2003; Maywood et al., 2006, 2011a; Liu et al., 2007). Thus, synchronization of neuronal subpopulations across the nucleus maintains coherent ensemble molecular and electrophysiological rhythms.

Recently, the classic GABAA-receptor antagonist picrotoxin was shown to accelerate the SCN clock, independently of its canonical role in antagonizing GABAA receptors (Freeman et al., 2013). In contrast to pharmacological acceleration, inhibition of casein kinase 1ε/δ (CK1ε/δ) by the antagonist PF-670462 (4-[1-Cyclohexyl-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl]-2-pyrimidinamine dihydrochloride) lengthens the period of explant SCN slices (Meng et al., 2010), as does KNK437 (N-Formyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-benzylidine-gamma-butyrolactam), an inhibitor of heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1; Buhr et al., 2010). Several genetic mutations also alter the period of the SCN oscillation. The Tau mutation, originally identified in Syrian hamsters, causes the SCN clock to run at 20 h (Ralph and Menaker, 1988) due to a point mutation within the CK1ε gene (Lowrey et al., 2000). The CK1εTau/Tau mutation has been genetically engineered in mice, and accelerates the clock through accelerated degradation of PER protein, thereby truncating the phase of transcriptional repression (Meng et al., 2008). In contrast, the Afterhours (Afh) mutation in the F-box/LRR-repeat protein 3 (Fbxl3Afh/Afh) slows CRY degradation and prolongs the transcriptional repression phase, driving the SCN to a ca. 28 h period (Godinho et al., 2007). Thus, Fbxl3Afh/Afh and CK1εTau/Tau have opposing actions, acting independently and additively (Maywood et al., 2011b).

The aim of this study was to combine these pharmacological and genetic manipulations to push the SCN clockwork beyond its normal period of oscillation, and by doing so reveal unanticipated cell-autonomous and emergent, circuit-level properties. To facilitate this, we developed a novel approach to analyze the profile of the PER2::LUC bioluminescent waveform, employing first derivative analysis (FDA). By conducting such a “stress test,” we anticipated three possible outcomes: complete arrhythmia; asynchrony of competent cellular oscillators in an incompetent circuit; or maintained cell-autonomous and circuit-level rhythms of extreme period, should the network contain sufficient temporal elasticity. We report that both the cell-autonomous and the circuit-level functions of the SCN are extremely robust in the face of these extreme perturbations, with an operating range of >25 h, extending from <17 h to >42 h. FDA waveform analysis at extreme periods revealed internal phase patterning to the circadian oscillation and differential phase sensitivity of the SCN to genetic and pharmacological manipulations. This was validated by examination of the interplay between the CK1εTau/Tau mutation and the specific CK1ε inhibitor PF-4800567. Thus, the SCN clock functions as a sequence of distinct stages and is remarkably robust and elastic at both cell-autonomous and circuit levels.

Materials and Methods

Slice preparation.

All animal work was licensed under the UK 1986 Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act and subject to local ethical review. SCN slices were isolated from 300-μm-thick coronal hypothalamic slices prepared from postnatal day 8 (P8) to P10 mice (either sex) and cultured on Millicell tissue culture inserts (PICMORG50, Millipore) for at least a week at 37°C, as previously described (Yamazaki et al., 2002; Hastings et al., 2005; Brancaccio et al., 2013). Slices were prepared from wild-type and circadian mutant mice, CK1εTau/Tau and Fblx3Afh/Afh, carrying the PER2::LUC reporter.

Bioluminescent recordings.

Slices were transferred to individual dishes containing DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with Glutamax, penicillin/streptomycin, FCS, B27, and beetle luciferin as described previously (Hastings et al., 2005; Brancaccio et al., 2013). Dishes were sealed with a glass coverslip and vacuum grease, placed under a photomultiplier tube (PMT; H9319–11 photon-counting head, Hamamatsu), and maintained at 37°C in a nonhumidified incubator. Bioluminescence recordings were made at 1 s intervals, binned into 6 min epochs for subsequent analysis and monitored in real-time for at least five full cycles at each condition (baseline, pharmacological manipulation, and washout). Immortalized fibroblasts produced from lungs of PER2::LUC mice (kindly provided by J. O'Neill, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology) were seeded into 33 mm dishes to confluence (O'Neill and Hastings, 2008) 24 h before entrainment. Medium was then changed to supplemented DMEM (as detailed for SCN explants), and dishes were sealed before transfer to a computer-controlled incubator (Galaxy 48R, New Brunswick Scientific) for entrainment to a temperature cycle (12 h 32°C, 12 h 37°C) over four cycles. On the final warm phase, cells were treated with either 500 μm picrotoxin or 0.5% DMSO and immediately transferred to PMTs to free run at 37°C, and continuous recordings of bioluminescence were made over 5 d.

For single SCN cell analysis, sealed dishes were transferred to the heated stage of an upright microscope, and bioluminescence was visualized by CCD camera. Time-lapse images of bioluminescent signals were taken at 1 h intervals over five cycles per condition. When 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) was applied to slices in the presence of test compounds, an additional 0.1 μm luciferin was added to the medium to attenuate the damping of the molecular oscillation that is characteristic of TTX treatment (Yamaguchi et al., 2003). After the experiment, individual ROI analysis was performed using the Semi-Automated Routines for Functional Image Analysis (SARFIA; Dorostkar et al., 2010) package in IGOR Pro as described previously (Brancaccio et al., 2013), and for each slice, >100 ROIs were identified. Center-of-luminescence (CoL) analysis was performed in IGOR Pro using custom in-house scripts to detect the frame-by-frame XY coordinates of the CoL as described previously (Brancaccio et al., 2013). Path indexes of the trajectories were calculated as total pixel excursion divided by the period of the oscillation, before normalization to the relative bioluminescent pixel area of the nucleus measured and expressed as a fraction of the baseline to account for differences in relative magnification between microscopes. All image analysis was performed in FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012) and IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics).

Drug treatments.

At least five full cycles after the start of an experiment, all applications were made as a 1:1000 to 5:1000 dilution of the compound plus vehicle directly into the baseline medium. Drugs and corresponding vehicle treatments were run simultaneously for each genotype. Picrotoxin and DMSO (final concentration, ≤0.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; PF-670462 and PF-4800567 (3-[(3-Chlorophenoxy)methyl]-1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine hydrochloride) from were purchased from R&D Systems; and KNK437, gabazine (SR-95531), and TTX citrate from were purchased from Cambridge Bioscience. Period-altering drugs were applied at maximally effective concentrations of 100 μm for picrotoxin, 1 μm for PF-670462, and 100 μm for KNK437.

Period analysis.

Period was analyzed using the Biological Rhythms Analysis Software System software running on the BioDARE platform at the University of Edinburgh (courtesy of A. Millar; http://www.biodare.ed.ac.uk/; Moore et al., 2014; Zielinski et al., 2014). The first 12 h of all recordings were ignored to remove any artifacts arising from medium change, the incubator being opened, etc. PMT data were analyzed as raw data without any detrending except in the case of fibroblast data, which were detrended with a 12 h moving average and smoothed with a centered moving average. The first 24 h of fibroblast data following entrainment were ignored, so that only free-running rhythms were analyzed. Relative amplitude error (RAE) and phase were obtained directly from the BioDARE output. All single-cell CCD data were detrended by a 12 h moving average and smoothed by a centered moving average before analysis in BioDARE to resolve low amplitude rhythms within the long-term recording. Where required, phase coherence was checked by manual calculation and resulted in comparable mean vector lengths to Rayleigh analysis performed using BioDARE-calculated values. Relative period range widths for single-cell experiments were calculated by subtracting the minimum period from the maximum period from the BioDARE-calculated values and dividing the resulting range width by the population mean period for that SCN.

Waveform analysis.

Waveform analysis was performed on individual peaks, with period and peak amplitude normalized to allow direct comparison across conditions. Peak amplitude was normalized between the 0 and 1 using unity-based normalization. The first derivative was calculated directly from the data using the Differentiate function in IGOR Pro. Data were integrated into bins of normalized period with 0.02 period bin widths to directly make comparisons across genotype and pharmacological conditions. FDA baseline subtraction (FDA-S) analysis was applied by subtracting the binned baseline values from the binned treatment values to map changes at each time point arising from vehicle or drug treatment. Peak identification was performed using GraphPad Prism to return peak coordinates from baseline-subtracted curves.

Statistical analysis.

Two-way ANOVA with Šidák's multiple comparisons test was performed on all FDA data sets to determine statistical significance within and between conditions. Where appropriate, repeated measures one-way ANOVA with the Greenhouse–Greisser correction or paired two-tailed t tests were applied to in-slice comparisons. One-way ANOVA and unpaired two-tailed t tests were applied to comparisons between different treatment populations. Where multiple comparisons were made with ANOVA, p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm–Šidák multiple comparison test. Rayleigh analyses were applied by converting phase data to circular data within Microsoft Excel, and performed on the native time base for the data sets, as determined by period analysis. Circular Rayleigh plots were produced using Oriana software (Kovach Computing Services). All statistics and data analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism, WaveMetrics IGOR Pro, and Microsoft Excel for Mac 2008.

Results

The SCN molecular clockwork can sustain extreme periods under combined genetic and pharmacological manipulations

The first aim of mapping the limits of SCN circadian period was to explore the operating range and robustness of the clock mechanism. Second, it was anticipated that pushing the SCN to extreme periods could selectively reveal critical phases in the oscillation, thereby identifying hidden aspects of its underlying structure. Using three compounds known to be efficacious in altering the period of the SCN: picrotoxin (Freeman et al., 2013); PF-670462, an inhibitor of CK1ε/δ (Meng et al., 2010); and KNK437, an inhibitor of HSF1 (Buhr et al., 2010), it was important to demonstrate the reversibility of any responses, to confirm that even at extreme periods the intrinsic mechanisms of the SCN remained fully competent and resilient to return to baseline. None of the compounds had a permanent effect on the period of PER2::LUC bioluminescence rhythms of wild-type SCNs (grouped baseline, 24.63 ± 0.10 h vs grouped washout, 24.69 ± 0.08 h; p = 0.65). Picrotoxin (100 μm) reversibly shortened the period of individual wild-type SCNs (pretreatment vs treatment, 25.07 ± 0.22 h vs 20.36 ± 0.34 h; p < 0.01; n = 8), whereas PF-670462 (1 μm) and KNK437 (100 μm) reversibly lengthened period (PF-670462, 24.51 ± 0.15 h vs 30.94 ± 0.26 h, p < 0.01, n = 8; KNK437, 24.45 ± 0.08 h vs 33.06 ± 0.21 h, p < 0.01, n = 8; Fig. 1A). The respective period changes were significantly different from the minimal effects of vehicle delivery (100 μm picrotoxin vs 0.1% DMSO, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; 1 μm PF-670462 vs 0.01% H2O, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; 100 μm KNK437 vs 0.5% DMSO, p < 0.01, n = 8/8).

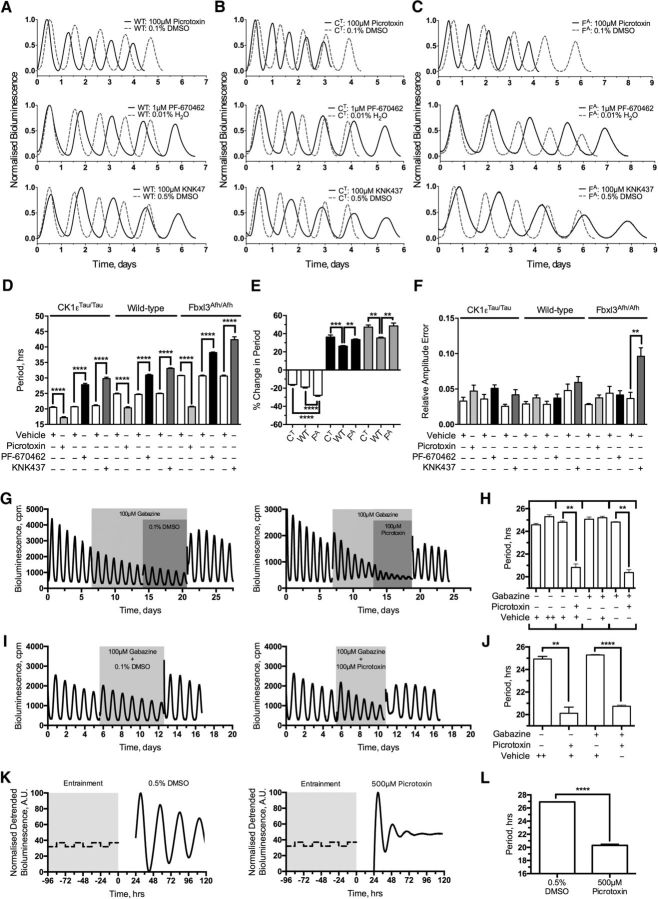

Figure 1.

Genetic and pharmacological manipulation of the SCN period greatly extends the operational range of explant SCN slices. A–C, Example PMT traces showing normalized bioluminescence for treatment intervals. Treatments are as follows: 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (top), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (middle), and 100 μm KNK437/0.5% DMSO (bottom). Treatment (solid black) is overlaid with vehicle traces (dashed gray) grouped by genotype. A, Wild-type PER2::LUC (WT). B, CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (CT). C, Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (FA). D, Summary period data expressed as mean ± SEM from each treatment condition grouped by genotype. Treatments accompanied by their specific vehicles (white) are 100 μm picrotoxin (light gray), 1 μm PF-670462 (black), and 100 μm KNK437 (dark gray), as indicated. E, Summary data expressing the proportional change in period expressed the percentage change from baseline period induced by period-altering compounds and expressed as mean ± SEM. Bars are grouped by pharmacological treatment: 100 μm picrotoxin (white), 1 μm PF-670462 (black), and 100 μm KNK437 (gray). Genotypes are identified as CK1εTau/Tau×PER2::LUC, wild-type PER2::LUC (WT) and Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC. F, Summary RAE expressed as mean ± SEM from each condition grouped by genotype. Treatments accompanied by their specific vehicles (white) are 100 μm picrotoxin (light gray), 1 μm PF-670462 (black), and 100 μm KNK437 (dark gray), as indicated. G, Example PMT traces for continuous wild-type SCN explant experiments cotreated in series with 100 μm gabazine and 100 μm picrotoxin (right) and 100 μm gabazine and 0.1% DMSO (left). Treatment intervals are indicated by gray shaded regions. H, Summary period data as mean ± SEM for series cotreatment experiment. Treatments are as indicated, and in-series treatments are grouped by brackets. I, Example PMT traces for continuous wild-type SCN explant experiments cotreated with 100 μm gabazine and 100 μm picrotoxin (right) and 100 μm gabazine and 0.1% DMSO (left). Treatment intervals are indicated by gray shaded regions. J, Summary period data as mean ± SEM for cotreated experiments. Treatments are as indicated. K, Fibroblast representative traces (detrended) for 500 μm picrotoxin treatment (right) and 0.5% DMSO treatment (left). L, Summary period data for fibroblast experiments as indicated. n values are detailed throughout the text. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Pharmacological manipulation was then applied to genetically modified SCNs, which exhibited the expected short (CK1εTau/Tau, 20.4 ± 0.28 h) and long (Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 28.67 ± 0.20 h) periods relative to wild-type slices (24.63 ± 0.10 h; Fig. 1B,C, vehicle traces). Picrotoxin (100 μm) shortened the period by ca. 4 h in CK1εTau/Tau SCNs, leading to an unprecedentedly short composite period of ca. 17 h (Fig. 1D; baseline, 20.43 ± 0.28 h vs treatment, 17.17 ± 0.31 h; p < 0.01; n = 8). The effect was fully reversed on washout, confirming that even at this extreme acceleration, the SCN maintained elasticity (pretreatment baseline, 20.22 ± 0.74 h vs washout, 20.48 ± 0.64 h; p = 0.81; n = 8). Picrotoxin accelerated the long-period mutant Fbxl3Afh/Afh by ∼8.0 h (Fig. 1C,D; baseline, 28.67 ± 0.20 h vs treatment, 20.67 ± 0.21 h; p < 0.01; n = 8). Surprisingly, this was comparable to the period of wild-type SCNs treated with picrotoxin; i.e., the effect of the mutation was completely masked (Fig. 1A,C,D; wild-type vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p = 0.46, n = 8/8). Comparison of the effects of picrotoxin across genotypes [Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 8.00 in 28.67 h (28%); wild-type, 4.71 in 25.07 h (19%); CK1εTau/Tau, 3.26 in 20.43 h (16%)] suggests that pharmacologically induced period shortening by picrotoxin was manifest neither as a simple proportional scaling across the cycle nor as a discrete reduction in solar hours (Fig. 1E).

To probe the upper limit of SCN resilience, the two period-lengthening compounds, PF-670462 and KNK437, were applied, and both slowed the circadian oscillation of SCN explants from all three genotypes (Fig. 1A–D). Application of 100 μm KNK437 caused the greatest deceleration of the clock, slowing the Fbxl3Afh/Afh oscillation by around 14 h to create SCNs with an unprecedentedly slow period of ca. 42 h (Fig. 1C,D; baseline, 28.53 ± 0.14 h vs treatment, 42.38 ± 0.93 h; p < 0.01; n = 8). Again, in comparing across genotypes the period lengthening by either PF-670462 [Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 9.36 in 28.6 h (33%); wild-type, 6.43 in 24.51 h (26%); CK1εTau/Tau, 7.40 in 20.42 h (36%)] or KNK437 [Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 13.85 in 28.53 h (49%); wild-type, 8.61 in 24.45 h (35%); CK1εTau/Tau, 9.55 in 20.24 h (47%)], it was clear that these changes were manifested neither by consistent proportional nor discrete absolute increases in period (Fig. 1E). Thus, across the three genotypes, each drug changed period in a qualitatively similar but unequal manner: the response to pharmacological treatments relied on the condition of the oscillator; i.e., period changes were manifested as an interaction between genetics and pharmacology.

Interestingly, this genetic and pharmacological interaction was most obvious with the period-lengthening compounds where both KNK437 and PF-670462 had larger effects in mutant than in wild-type SCN (Fig. 1E; wild type vs CK1εTau/Tau, 1 μm PF670462, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; 100 μm KNK437, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; wild type vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 1 μm PF670462, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; 100 μm KNK437, p < 0.01, n = 8/8). This suggests that these compounds have an upper limit of about 35 or 48% (for PF-670462 and KNK437, respectively) in proportionally extending the oscillation (Fig. 1E; CK1εTau/Tau vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 1 μm PF-670462, p = 0.18, n = 8/8; 100 μm KNK437, p = 0.70, n = 8/8). As seen for period shortening, with period lengthening there was also a significant interaction between pharmacology and genetic background that is not simply a proportional scaling. This is not wholly unexpected for the interaction between PF-670462 and the CK1εTau/Tau conditions where PF-670462 acts on the CK1-mediated axis of circadian timekeeping (Meng et al., 2010). It is, however, surprising that there is a larger proportional effect in both CK1εTau/Tau and Fbxl3Afh/Afh slices treated with KNK437, where a relationship between genetics and pharmacology would not necessarily be expected.

Thus, molecular timekeeping in the SCN, a biological clock that has evolved to operate at a period of ca. 24 h, has limits of operation that span at least between 17 and 42 h (a range of 25 h, i.e., >100% of the normal period), and even when pushed to such extremes, it retains complete elasticity. Moreover, visual inspection of the bioluminescence curves suggested that at these extreme periods, the oscillation maintained coherence. This was confirmed by the RAE, an inverse index of overall coherence (Fig. 1F). In all cases except one, RAE was unaffected by drug application when compared to baseline (data not shown) or to vehicle treatment (Fig. 1F). The exception was seen in Fbxl3Afh/Afh SCNs treated with 100 μm KNK437 (baseline RAE, 0.044 ± 0.005 vs treatment RAE, 0.096 ± 0.012; p = 0.011; n = 8; Fig. 1F). This reduced coherence at the extremely long period suggests that the upper limit of the temporal elasticity of the SCN network was near. It should be noted, however, that in genetically disrupted SCNs, for example, with combined null mutations of Per1 and Per2, or deletion of VIP or Vipr2 (which encodes the receptor for VIP), the RAE lies in the range of 0.15 to 0.20 (Maywood et al., 2011a, 2014), far beyond that seen here. Thus, the circuit-level circadian functions of the SCN are highly elastic and can sustain molecular oscillations that range in period between 17 and 42 h without a significant loss of temporal coherence.

The SCN network is predominately a GABA-ergic circuit, and picrotoxin is a classical GABAA-receptor antagonist. Although the role of GABAA-receptor antagonism in reducing period has been discounted previously (Freeman et al., 2013), the precise role of GABA in SCN timekeeping is still unknown. To further determine that period effects are due to an as yet unknown target of picrotoxin, wild-type slices were cotreated with the GABAA-receptor antagonist gabazine (SR-95531) and picrotoxin in two configurations: serial and simultaneous treatments. With serial treatment (Fig. 1G,H), slices received 100 μm gabazine for five cycles before 100 μm picrotoxin or 0.1% DMSO was applied (Fig. 1G). Preantagonism of GABAA receptors did not induce a period change (baseline, 24.60 ± 0.08 h vs 100 μm gabazine, 24.82 ± 0.04; p = 0.18; n = 3), and furthermore, this did not occlude (100 μm gabazine alone vs with 100 μm picrotoxin, p < 0.01, n = 3) or attenuate the action of picrotoxin (100 μm picrotoxin, 100 μm gabazine pretreatment vs 0.1% DMSO pretreatment; p = 0.32; n = 3/3; Fig. 1H). In the simultaneous treatment configuration (to control for any potential loss of efficacy in gabazine in the serial treatment configuration), gabazine was coapplied to slices with either picrotoxin or DMSO (Fig. 1I). Again, gabazine did not occlude (baseline, 24.50 ± 0.07 h vs 100 μm gabazine/100 μm picrotoxin, 20.74 ± 0.10 h; p < 0.01; n = 3; 100 μm gabazine coapplied, 100 μm picrotoxin vs 0.1% DMSO, p < 0.01, n = 3/3) or attenuate the picrotoxin-induced period change (100 μm picrotoxin coapplied, 100 μm gabazine vs 0.1% DMSO, p = 0.33, n = 3/3; Fig. 1J). Thus, acceleration by picrotoxin in the SCN is not induced via GABAA-receptor antagonism. To further confirm that picrotoxin affects the circadian clock directly and does not act via GABA-ergic synaptic signaling, PER2::LUC fibroblasts were treated with either 500 μm picrotoxin or 0.5% DMSO immediately following four cycles of temperature entrainment (Fig. 1K). Consistent with previous reports (Freeman et al., 2013), 500 μm picrotoxin caused a reduction of period compared to vehicle treatment (500 μm picrotoxin vs 0.5% DMSO, p < 0.01, n = 6/6; Fig. 1L). These experiments confirm that antagonism of synaptic GABAA receptors by picrotoxin is not a requisite for setting period length.

Manipulating the period alters the waveform of the circadian PER2 bioluminescence profile

Having created SCNs with extreme circadian periods, the next aim was to use them to probe the internal structure of the oscillation. Theoretically, changing the period could be achieved in one of two ways: first, by a global proportional scaling of the oscillation across all phases, and second, by a phase-specific scaling where different phases are more sensitive to particular interventions. The former would be compatible with traditional parametric models of the oscillator (Fuhr et al., 2015), whereas the latter would indicate it to be a series of distinct stages, and indeed the interaction between drug and genotype in setting SCN circadian period is supportive of the latter. To discriminate directly and quantitatively between these alternatives in genetically modified SCNs, individual cycles were peak aligned with the wild-type condition (peak PER2::LUC is circadian time 12, i.e., subjective dusk; Fig. 2A–C, top). When plotted in solar time, this revealed that CK1εTau/Tau and Fbxl3Afh/Afh produced phase-specific effects relative to peak bioluminescent activity (Fig. 2A,B, top). To test for putative global effects, the profiles were then replotted after normalization to their specific periods (Fig. 2A,B, middle), when overlapping plots would represent a global effect of the mutation. This revealed, however, that both mutations produced phase-specific shifts in the standardized waveform that deviated significantly from wild type. Whereas CK1εTau/Tau exhibited a relative increase in PER2::LUC early in circadian day compared to wild type, the Fbxl3Afh/Afh profile exhibited a relative decrease in PER2::LUC later in the circadian day. The effects of the mutations were therefore phase specific rather than global.

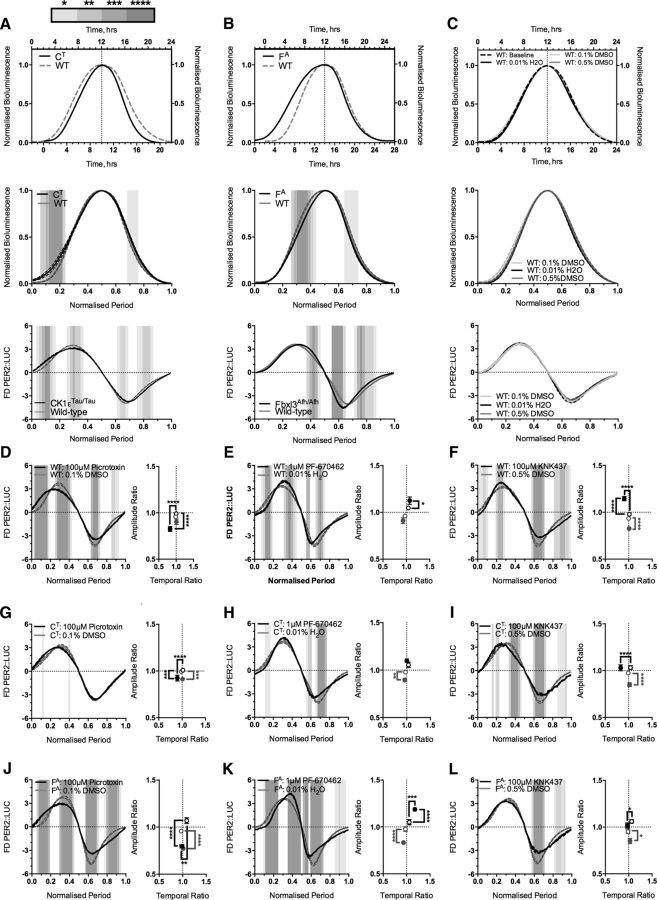

Figure 2.

Representative single peaks demonstrate alterations in waveform profile caused by genetic manipulation of explant SCN period. A–C, Top panels show composite single normalized cycles (solid black) peak aligned and overlaid with wild-type PER2::LUC traces (WT; dashed gray). The top x-axis displays time in hours for the wild-type PER2::LUC trace, and the bottom x-axis displays time in hours for the PER2::LUC trace of the aligned condition. Central panels display peak-aligned traces as in the top panel on a normalized time base (normalized period). Bottom panels display mean waveform profiles as first derivative of normalized bioluminescence (FD PER2::LUC) versus the normalized period as wild-type profile (solid gray) overlaid with period mutants (solid black). A, CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (CT). B, Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (FA). C, Wild-type PER2::LUC slices (WT) treated with vehicle, as follows: baseline (dashed black; top only), 0.1% DMSO (solid light gray), 0.01% H2O (solid black), and 0.5% DMSO (solid dark gray). D–L, Left, Mean first derivative plot of vehicle-treated (solid gray) or period-altering-compound-treated (solid black) normalized PER2::LUC bioluminescence (FD PER2::LUC). Right, Constellation plots showing mean shifts in peaks of PER2 accumulation (black) and dissipation (gray). Hollow symbols indicate vehicle treated values, and solid symbols indicate drug-treated values. Values are shown as mean ±SEM in both x (temporal ratio) and y (amplitude ratio) directions, and significance is indicated by square brackets for either accumulation (black) or dissipation (gray). Treatments are shown on different genetic backgrounds: wild-type PER2::LUC (D–F), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (D), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (E), 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (F); CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (G–I), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (G), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (H), 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (I); Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (J–L), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (J), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (K), 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (L). First derivative plots and alignments on a normalized time base are shown as mean ± SEM as error banding. For normalized period-aligned plots, gray shading indicates the level of significant difference as assessed by two-way ANOVA, graded by lightest (p < 0.05) to darkest (p < 0.0001), as indicated in the key above A. n values are detailed throughout the text. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

To examine these effects more precisely, the first derivative of the period-normalized waveform was calculated, so that the relative rate at which the reporter expression changed over time could be followed quantitatively (Fig. 2A–C, bottom). FDA of the wild-type PER2::LUC waveform revealed that circadian cycling of PER2 followed a specific, general pattern of accumulation and decline that is reproducible over the whole cycle (Fig. 2A–C, bottom). The pattern of accumulation and decline was significantly different in the mutant waveforms, compared to wild type (Fig. 2A,B, bottom). These shifts in FDA suggest that circadian time is encoded as a series of progressive phases, with differential genetic susceptibility, i.e., period changes arising from single genetic manipulations alter the dynamics of these phases selectively, perturbing the resultant profile away from the wild-type trajectory.

Alterations in waveform profile indicate phase-specific points of sensitivity within the oscillator

As FDA measures how bioluminescence changes over time, by inference it can be used to identify critical intervals where pharmacological manipulation alters peak rates of PER2 accumulation or dissipation. This was exploited across all combinations of genotype and pharmacological manipulation. Shifts in the amplitude and the temporal positions of the maximal rate of increase or decrease in PER2 levels can be expressed as two separate ratios (one for each parameter) between treatment and baseline (Fig. 2D–L, right). First, however, to ensure that the waveform arrangement is not altered by treatment with vehicle, the three different vehicle treatments were coplotted and aligned on a solar or normalized time base and as FDA plots (Fig. 2C). This revealed no significant difference (two-way ANOVA) arising either from vehicles (0.1% DMSO vs 0.01% H2O vs 0.5% DMSO, p = 0.17) or from interaction between time and vehicles (0.1% DMSO vs 0.01% H2O vs 0.5% DMSO, p = 0.59). As there were no significant changes in waveform induced by vehicle treatment, all subsequent comparisons of waveform were made between vehicle and drug.

Picrotoxin reduced the peak amplitude of PER2 accumulation across genotypes compared to vehicle (Fig. 2D,G,J; all vs DMSO, wild type, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Tau, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.01, n = 8/8). The effect increased as the underlying genetic period increased, with the Fbxl3Afh/Afh mutant producing the largest reduction in amplitude (Fig. 2J). Across all genotypes, this amplitude effect was associated with an earlier position of the accumulation peak (Fig. 2D,G,J; all vs DMSO, wild type, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Tau, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.02, n = 8/8), although it should be noted that the decrease in temporal position seen in the Fbxl3Afh/Afh was very subtle. Picrotoxin also decreased the peak amplitude of dissipation across genotypes (Fig. 2D,G,J; all vs DMSO, wild type, p = 0.031, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Tau, p = 0.0005, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.01, n = 8/8), but without shifting its temporal position. These results suggest that picrotoxin exerts a general effect of reducing the amplitude of peak PER2 accumulation and pushing it earlier in the cycle, whereas PER2 dissipation occurs at the same temporal position but again with a reduced peak rate.

PF-670462 increased the amplitude of the peak rate of accumulation across wild-type and Fbxl3Afh/Afh slices (Fig. 2E,K; all vs water, wild type, p = 0.03, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.01, n = 8/8). The effect was not significant in CK1εTau/Tau slices (Fig. 2H; PF-670462 vs water, p = 0.12, n = 8/8). PF-670462 did not affect the temporal position of the accumulation peak in either the wild type or CK1εTau/Tau conditions (Fig. 2E,H), but did delay the accumulation peak of Fbxl3Afh/Afh (Fig. 2K; PF-670462 vs water, p = 0.0002, n = 8/8). Across genotypes, PF-670462 caused a reduction in amplitude of the peak PER2 dissipation rate (Fig. 2E,H,K; PF-670462 vs water, wild type, p < 0.04, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Tau, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.01, n = 8/8), but there was no significant effect on the timing of the peak (Fig. 2E,H,K). Thus, PF-670462 generally increases the rate of PER2 accumulation and decreases the subsequent dissipation of PER2 levels, consistent with the idea that PF-670462-mediated inhibition of CK1ε/δ slows down the clock by sustaining elevated levels of PER2 protein by inhibiting its degradation (Lee et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2010).

The HSF1 inhibitor KNK47 caused an earlier peak rate of PER2 accumulation across all genotypes (Fig. 2F,I,L; all vs DMSO, wild type, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Ta, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p = 0.024, n = 8/8). In the wild-type SCNs, this shift was associated with an increase in the rate of PER2 accumulation (Fig. 2F; p < 0.01, n = 8/8) that was absent in the CK1εTau/Tau and Fbxl3Afh/Afh mutants (Fig. 2I,L). Across all genotypes, the peak amplitude of PER2 dissipation rate was also reduced (Fig. 2F,I,L; all vs DMSO, wild type, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; CK1εTau/Tau, p < 0.01, n = 8/8; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p = 0.012, n = 8/8), without any effect on the timing of the peak. These results suggest that KNK437 treatment shifts PER2 accumulation to an earlier phase of the cycle without affecting the amplitude of the peak rate of accumulation. This early burst of PER2 accumulation combined with the severe reduction of its amplitude could extend the SCN period because PER2 takes longer to accumulate to a physiologically relevant level for clock progression.

FDA therefore indicated a shared general effect of the period-altering drugs on the peaks of the waveform profile regardless of genetic background. Nevertheless, while the direction of the change is dictated principally by pharmacology, the degree of difference in the peak rate of PER2 accumulation or dissipation was again dictated by the interaction between pharmacology and genetics. These shifts in PER2 dynamics thereby indicate sensitive phases or “checkpoints” in the circadian cycle that can be differentially probed through interacting genetic and pharmacological manipulations.

Pharmacological manipulation of the SCN clockwork has a time-stamped phase effect regardless of underlying genotype

To further explore and characterize the phase-specific changes to the circadian oscillation, FDA during baseline was subtracted from the corresponding FDA during drug treatment (Fig. 3). This would cancel out any genotypic effect and thereby reveal any specific drug effect. FDA-S was validated using vehicle treatment, where there should be little difference between the baseline and treatment curves, and indeed this was the case across all genotypes (two-way ANOVA, 0.1% DMSO vs 0.01% H2O vs 0.5% DMSO, CK1εTau/Tau, p > 0.99; wild type, p > 0.99; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p > 0.99) and between the different genotypes within vehicle treatment (CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 0.1% DMSO, p = 0.99; 0.01% H2O, p = 0.95; 0.5% DMSO, p = 0.99). Thus, FDA-S was used to identify general phase-specific patterning across the cycle in response to pharmacological manipulation.

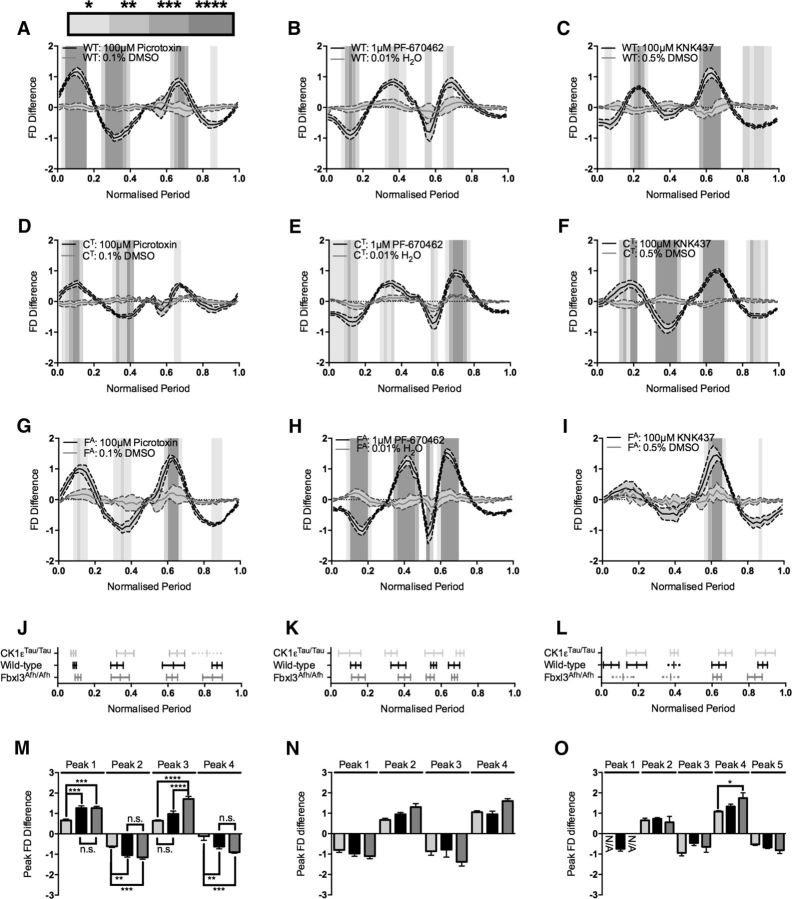

Figure 3.

Baseline subtraction (FDA-S) reveals phase-specific pharmacological patterning. A–I, Baseline-subtracted treatment cycles (FD Difference) versus normalized period ordered by genotype and treatment. Vehicle (solid gray) and treatment (solid black) are coplotted as mean ± SEM as shaded error banding. The significant differences between vehicle and treatment determined by two-way ANOVA are indicated by graded gray shading as detailed in the key above A. Treatments are as follows: wild-type PER2::LUC (WT; A–C), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (A), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (B), and 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (C); CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (CT; D–F), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (D), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (E), and 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (F); Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (FA; G–I), 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (G), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (H), 100 μm KNK/0.5% DMSO (I). J–L, Phase-specific patterning across the cycle showing the temporal alignment of CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (light gray), wild-type PER2::LUC (black), and Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (dark gray) treated with period-altering compounds. Bars show mean peak position ± SD. Solid-capped bars show phase intervals that are significantly different from vehicle in A–I. Dotted uncapped bars show phase intervals that have been identified only via automated peak identification. Treatment and vehicle identities are as follows: 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (J), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (K), and 100 μm KNK437/0.5% DMSO (L). M–O, Peak amplitudes of peak phase patterning intervals (Peak FD Difference) illustrated in J–L. Bars are mean ± SEM and indicate the difference between vehicle and treatment for particular genotypes: CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (light gray), wild-type PER2::LUC (black), and Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC (dark gray). Significant differences are noted by square brackets. Treatment and vehicle identities are as follows: 100 μm picrotoxin/0.1% DMSO (M), 1 μm PF-670462/0.01% H2O (N), and 100 μm KNK437/0.5% DMSO (O). n values are detailed throughout the text. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Picrotoxin FDA-S revealed a general time-stamped patterning of sensitive phases to treatment regardless of genetic background (Fig. 3A,D,G,J). These phases are highlighted by peaks in the FDA-S profile at which there were significant differences between vehicle and treatment. Interestingly, in the picrotoxin-treated CK1εTau/Tau FDA profile comparison, the vehicle-treated FDA profile appears to mask low-amplitude changes in the picrotoxin-treated waveform (Fig. 2G) that are revealed in the FDA-S profile at two points (Fig. 3D): toward the start of the cycle and just after the PER2 peak. Thus, FDA-S analysis was able to unmask changes in the profile undetected by the FDA approach, adding sensitivity to this analytical approach. In addition to this unmasking of sensitive phases, FDA-S revealed that the pattern of phase-specific pharmacological sensitivity across genotypes followed the same general trend in directionality, and that the temporal position of the peaks coincided in circadian time (Fig. 3J,M). The exception to this lay in the case of the final peak of CK1εTau/Tau, where the amplitude of the difference was too low to register as significant when the picrotoxin profile was compared to the vehicle profile (Fig. 3D). However, automated peak identification enabled the mapping of this peak, which registered with the phase patterning of the other genotypes (Fig. 3J) and had a severely and significantly reduced amplitude (peak 4; CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type, p < 0.01; CK1εTau/Tau vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, p < 0.01; Fig. 3M).

Interestingly, while the phases of the critical points of manipulation were approximately the same across genotypes, the amplitudes of the phase-specific changes were significantly different between different phases and genotypes (Fig. 3A,D,G,M). If these differences arose solely as a result of the pharmacological treatment, then the amplitude of difference between the three genotypes should not vary. If, however, there were differences between the genotypes, this could arise from a synergistic phase-specific genotype by pharmacology interaction. This synergistic interaction would be most informative when the difference occurred between wild-type and circadian mutants, as this could point to a mechanism where the clockwork is more or less sensitive to a particular manipulation due to genetics. Applying this analysis to 100 μm picrotoxin revealed a significant reduction in amplitude between CK1εTau/Tau and wild type during the first two peaks (CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type, peak 1, p < 0.01; peak 2, p < 0.01). This indicates that the CK1εTau/Tau mutant is less sensitive to picrotoxin treatment at these particular phases, which resulted in a smaller difference between the genotype and the pharmacological treatment.

As with picrotoxin, FDA-S revealed a unique fingerprint of phase-specific patterning in 1 μm PF-670462-treated waveforms (Fig. 3B,E,H,K). This registered to a high degree across genotypes, with the phases of all four peaks aligning across the cycle (Fig. 3K). Different from the picrotoxin-treated slices, PF-670462 also produced comparable changes in amplitude across the genotypes tested (Fig. 3N). As there was no significant difference in either amplitude or phase-sensitive patterning across genotypes, this indicates that treatment with 1 μm PF-670462 induced the same changes across genotypes. This could be due to the fact that this compound acts on both the CK1ε and CK1δ isoforms, and therefore reverses the effects of the CK1εTau/Tau mutation to an approximately wild-type level and affects CK1δ to the same degree across genotypes, causing the characteristic period-lengthening effects of this drug (Meng et al., 2010) and clamping the waveform into a particular phase pattern.

FDA-S of KNK437-induced waveforms revealed a general phase-specific patterning comprising four peaks that is visually present at low amplitude across all three genotypes (Fig. 3C,F,I), although it was too low to achieve significance (Fig. 3L). This lack of phase-specific patterning was lost between the three genotypes at the beginning of the cycle, but was observed with a high degree of registration and significance at the end of the cycle (Fig. 3C,F,I,L). Looking at the waveforms in detail, CK1εTau/Tau highlights the four canonical KNK437 phases that could still be identified across the other two genotypes, albeit at low amplitude (peaks 2–5; Fig. 3F,L). This low amplitude footprint was again mapped by automated peak identification with a high degree of registration when coplotted (Fig. 3L), but the first two canonical peaks [peaks 2 (Fbxl3Afh/Afh) and 3 (wild type and Fbxl3Afh/Afh)] could be distinguished from the vehicle waveform by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 3C,I,L). Automated peak registration revealed that although there was a low amplitude difference at the second and third peaks, there was no significant difference between the genotypes. This suggests the possibility of a functional limit to FDA-S (as the period extreme is reached), where amplitude of the oscillation is reduced and the individual waveforms become too noisy to discriminate by direct waveform comparison. This peak identification approach suggests that the four canonical peaks (peaks 2–5) comprise the central footprint for KNK437 treatment preserved across genotypes (Fig. 3L,O).

Remarkably, FDA-S revealed that pharmacological treatment generally appears to cause a phase-specific patterning of the waveform, where certain phases are revealed to be more or less sensitive to manipulation. This phase-patterned fingerprint allows the identification of synergistic interactions between genotype and pharmacology and allows the potential identification of cryptic clockwork mechanisms. Thus, the FDA/FDA-S approach reveals that manipulation of period genetically, pharmacologically, or in combination manifests as a change in waveform (Fig. 2) that is not revealed by peak alignment alone. Finally, the FDA-S approach also reveals that pharmacologically induced changes in waveform have a phase-specific pattern of manipulation. The temporal patterning of this is independent of genotype, but the amplitude of the change at sensitive phases represents a genotype by pharmacology interaction (Fig. 3).

Waveform profile does not encode network period, but can reveal phase-specific core clock mechanisms

To make an independent assessment of the validity of FDA/FDA-S to test the relationship between period and pharmacologically sensitive phases of the oscillation, CK1εTau/Tau SCNs were titrated with a range of doses of the CK1ε specific inhibitor PF-4800567 (3-[(3-Chlorophenoxy)methyl]-1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine hydrochloride) (Fig. 4), a drug that selectively lengthens the period of CK1εTau/Tau rhythms with minimal effect on wild-type slices (Meng et al., 2010). Through use of this pharmacological manipulation to oppose a genetic manipulation and reset period, in theory, the wild-type and CK1εTau/Tau SCNs should exist with identical periods but different genetics. PF-4800567 at 0.5 μm drove the CK1εTau/Tau slices to the wild-type 24 h period (Fig. 4A,B; baseline, 20.00 ± 0.10 h vs 0.5 μm PF-4800567, 23.83 ± 0.20 h; p < 0.01; n = 6). FDA comparison of CK1εTau/Tau slices treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 revealed a significant shift in the waveform profile across the cycle (two-way ANOVA; Fig. 4C). As the CK1εTau/Tau mutation accelerates the circadian clock through dysregulated phosphorylation of the PER proteins (Lowrey et al., 2000; Meng et al., 2008, 2010; Maywood et al., 2014), pharmacological attenuation of CK1ε activity should return the CK1εTau/Tau waveform to the wild-type profile if waveform is directed solely by period. To test this, two comparisons with the wild-type profile were made. First, comparison of the baseline genetic waveform (CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type; Fig. 4D) showed that the baseline profiles were significantly different in broadly the same phases as CK1εTau/Tau baseline and CK1εTau/Tau 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (Fig. 4C). Second, comparison between the wild-type baseline and CK1εTau/Tau 0.5 μm PF-4800567-treated profiles (Fig. 4E) revealed that this dose of PF-4800567 partially reversed the CK1εTau/Tau mutation, but still left a significant mismatch between profiles in the latter half of the cycle. This indicates that the CK1εTau/Tau mutation is sensitive to pharmacological inhibition in the first half of the cycle but not in the second half. From this, a reasonable conclusion is that the CK1εTau/Tau mutation exerts influence over the period of the oscillation through inappropriately phased activity at the start of the cycle.

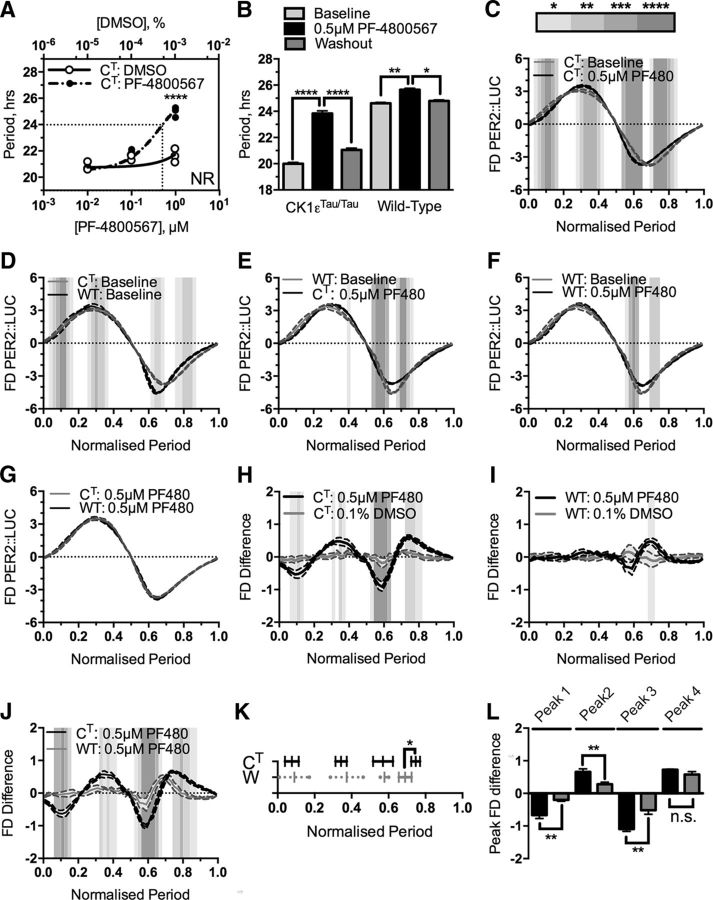

Figure 4.

First derivative plots reveal differential sensitivity of genotypes to pharmacological manipulation. A. Dose–response curve of CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC genotype titrated with increasing concentrations of the CK1ε inhibitor PF-4800567 (solid black circles) and DMSO (hollow circles). The critical dose to return CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC to the wild-type period is indicated by the dotted line. NR indicates that at 10 μM, slices become nonrhythmic. B, Summary period data for baseline (light gray), 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (black), and washout (dark gray) in CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC slices and wild-type PER2::LUC slices. Genotype is indicated below the bars. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. C–G, First derivative of normalized bioluminescence (FD PER2::LUC) versus the normalized period showing CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (CT: 0.5 μm PF480; C, black) overlaid with CK1εTau/Tau baseline (CT: Baseline; gray), wild-type PER2::LUC baseline (WT: Baseline; D, black) overlaid with CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC baseline (CT: Baseline; gray), CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (CT: 0.5 μm PF480; E, black) overlaid with wild-type PER2::LUC baseline (WT: Baseline; gray), wild-type PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (WT: 0.5 μm PF480; F, black) overlaid with wild-type baseline (WT: Baseline; gray), and CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (CT: PF480; G, black) overlaid with wild-type PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (WT: PF480; gray). Values are mean ± SEM, indicated by shaded error banding. H–J, Baseline subtraction showing (FD Difference) CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with either 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (black) or 0.1% DMSO (gray; H), wild-type PER2::LUC treated with either 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (black) or 0.1% DMSO (gray; I), and CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (black) overlaid with wild-type PER2::LUC treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (gray; J). Values are mean ± SEM, indicated as shaded error banding. K, Phase-specific patterning across the cycle showing the temporal alignment of CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (CT; black) and wild-type PER2::LUC (WT; gray) peaks from slices treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567. Bars show mean peak position ± SD. Solid capped bars show phase intervals that are significantly different from vehicle in H and I. Dotted uncapped bars show phase intervals that have been identified only via automated peak identification. L, Peak amplitudes of peak phase patterning intervals highlighted in K. Bars are mean ± SEM and indicate the absolute amplitude for either CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC (black) or wild-type PER2::LUC (gray). Significant differences are noted by square brackets. Significant differences for first derivative plots (C–G) and baseline subtractions (G–J) are indicated by graded gray shading as described in the key in C. n values are detailed throughout the text. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

The remaining mismatches between wild-type and CK1εTau/Tau slices treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 suggested two things. Either waveform profile is not a product of the period expressed, or returning the SCN clock to wild-type levels pharmacologically is more complicated than simply manipulating the period, i.e., there is a significant interaction between genotype and pharmacology that established circadian analyses do not reveal. To investigate this interaction further, wild-type slices were treated with the same dose of PF-4800567 as the CK1εTau/Tau slices (Fig. 4B,F). This caused a small but significant increase in period (Fig. 4B; baseline, 24.61 ± 0.07 h vs 0.5 μm PF-4800567, 25.65 ± 0.12 h; p = 0.002; n = 5), which differs from previous reports that PF-4800567 is ineffective on wild-type SCNs (Meng et al., 2010; Pilorz et al., 2014). Closer analysis of the waveform profile showed that there was a significant mismatch between baseline and 0.5 μm PF-4800567-treated profiles (Fig. 4F) that broadly occurred in the same phases as the mismatch between wild-type baseline and CK1εTau/Tau treated with 0.5 μm PF-4800567 (Fig. 4E). Due to the persistent mismatch in the latter half of the cycle in both treated conditions, these conditions were compared in a coplotted FDA, which showed that the profiles became completely aligned with no significant difference (Fig. 4G). These results revealed differential phases of regulation for the wild-type and Tau versions of the CK1ε enzyme, where the wild-type version predominately directs PER2 destabilization in the latter half of the cycle (Fig. 4F), while the Tau mutant becomes active at the beginning of the cycle, and it is presumably this “inappropriately phased” gain-of-function activity that causes the marked period acceleration (Fig. 4B).

This period mismatch was further backed-up by the FDA-S analysis (Fig. 3). This revealed that there were large shifts in the waveform in the first three quarters of the cycle for CK1εTau/Tau slices treated with PF-4800567 that were absent from the wild-type slices (Fig. 4H–K; CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type, peak 1, p < 0.01, n = 6/5; peak 2, p < 0.01, n = 6/5; peak 3, p < 0.01, n = 6/5). The final sensitive phase of the cycle had a shifted temporal positioning between CK1εTau/Tau and wild type (CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type, peak 4, p = 0.01, n = 6/5), but did not show any significant difference in magnitude (Fig. 4J,K; CK1εTau/Tau vs wild type, peak 4, p = 0.11, n = 6/5). Due to the very specific action of this drug on the CK1ε isoforms (Walton et al., 2009), the FDA-S also revealed an expected genotype and pharmacology interaction in CK1εTau/Tau treated slices, which is especially evident when compared to the non-responsive patterning of the wild-type treated slices (Fig. 4J,K). Together, these results indicate that the first derivative analysis is a useful tool for interrogating clock function mechanistically across the cycle and that FDA-S reveals not only pharmacological phase-specific patterning, but also significant internal phases where genotype and pharmacology interact.

Network and cell-autonomous properties of the SCN are maintained at extreme periods

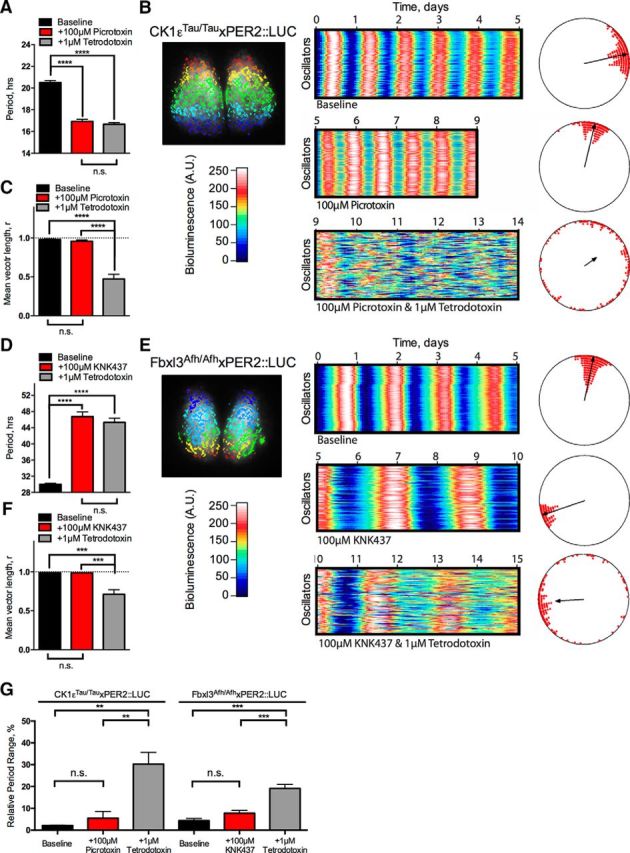

Bioluminescence recorded by PMT is the integrated product of signal across the SCN slice. At extreme periods, this may or may not mask alterations to circuit-level function. To explore the relationship between changes in waveform and period in the context of cell-autonomous and circuit-level properties of the SCN, slices oscillating at the two extreme periods were visualized directly by CCD camera to achieve cellular resolution of bioluminescence (Fig. 5). SARFIA analytical routines identified individual oscillators (presumed cells) across the network. In CK1εTau/Tau slices treated with 100 μm picrotoxin, individual oscillators maintained the characteristic pharmacologically determined period of the aggregate signal (Fig. 5A; baseline vs treatment, p < 0.01, n = 4) and remained in phase alignment with each other as assessed by raster plots and Rayleigh analysis (Fig. 5B,C; mean vector length, baseline vs treatment, p = 0.53, n = 4). In Fbxl3Afh/Afh slices treated with 100 μm KNK437, individual oscillators still sustained the extreme long period of the aggregate signal (Fig. 5D; baseline vs treatment, p < 0.01, n = 4) and maintained robust synchrony across the network (Fig. 5E,F; mean vector length: baseline vs treatment, p = 0.83, n = 4). Thus, the ability of the SCN to sustain extremely long or extremely short circadian periods is an integral property of the circuit, and the mechanisms that mediate synchrony can operate effectively over a wide range of nontypical periods that extends at least between 17 and 46 h. Importantly, the changes in waveform that accompany divergent periods are not a consequence of changes in phase synchrony across the network.

Figure 5.

Network and cell-autonomous properties of the SCN are unaffected by pushing period to short or long extremes. A–F, SARFIA single-cell imaging analysis of CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 100 μm picrotoxin (A–C) and Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC treated with 100 μm KNK437 (D–F). A, Summary period data from individual oscillators shown as mean ± SEM for baseline (black), 100 μm picrotoxin (+100 μm picrotoxin; red), and 100 μm picrotoxin/1 μm TTX cotreatment (+1 μm TTX; gray). B, Individual oscillators were assessed by SARFIA identification and analysis of ROIs, indicated as color-coded regions on the inset bioluminescent SCN image (left). Raster plots of 100 individual representative oscillators within the SCN are shown for baseline (top), 100 μm picrotoxin (middle), and 100 μm picrotoxin/1 μm TTX cotreatment (bottom). Relative bioluminescence intensity is color coded according to the color bar. Rayleigh plots are shown next to their corresponding raster plot. Phases of individual oscillators are plotted as circles, and the degree of synchrony is indicated by the length of the vector in the center. C, Summary synchrony data reported as mean vector length from individual Rayleigh analyses. Values are shown as mean ± SEM for baseline (black), 100 μm picrotoxin (red), and 100 μm picrotoxin/1 μm TTX cotreatment (gray). D, Summary period data from individual oscillators shown as mean ± SEM for baseline (black), 100 μm KNK437 (+100 μm KNK437; red), and 100 μm KNK437/1 μm TTX cotreatment (+1 μm TTX; gray). E, Individual oscillators were assessed by SARFIA identification and analysis of ROIs, indicated as color-coded regions on the inset bioluminescent SCN image (left). Raster plots of 100 individual representative oscillators within the SCN are shown for baseline (top), 100 μm picrotoxin (middle), and 100 μm KNK437/1 μm TTX cotreatment (bottom). Relative bioluminescence intensity is color coded according to the color bar. Rayleigh plots shown next to their corresponding raster plot. Phases of individual oscillators are plotted as circles, and the degree of synchrony is indicated by the length of the vector in the center. F, Summary synchrony data reported by mean vector length from individual Rayleigh analyses. Values are shown as mean ± SEM for baseline (black), 100 μm KNK437 (red), and 100 μm KNK437/1 μm TTX cotreatment (gray). G, Relative period range width from individual oscillators identified by SARFIA analysis in A and D expressed as a percentage of the overall cellular period. Values are shown as mean ± SEM for baseline (black), treatment (red), and TTX cotreatment (gray). Period-altering treatment conditions are detailed below the bars (+100 μm picrotoxin or +100 μm KNK437), and genotypes are detailed above the bars (CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC or Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC). n values are detailed throughout the text. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

To determine the relative contributions of cell-autonomous and circuit-level mechanisms to the maintenance of extreme periods in synchronized SCN, TTX was added during pharmacological treatment. TTX uncouples the SCN network by blocking action potential firing, leading to progressively damped and desynchronized SCN cellular oscillations (Yamaguchi et al., 2003; Hastings et al., 2007). In CK1εTau/Tau SCN treated with 100 μm picrotoxin (Fig. 5A–C), individual cells lost phase coherence when treated with TTX (Rayleigh mean vector, 100 μm picrotoxin alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p < 0.01, n = 4). Moreover, the coherence of individual cellular rhythms as assessed by the RAE was reduced by TTX (100 μm picrotoxin, alone, 0.08 ± 0.01 vs 1 μm TTX, 0.34 ± 0.10; p = 0.03; n = 4). Nevertheless, the overall cellular period was not significantly different from that of SCNs without TTX (100 μm picrotoxin alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p = 0.34, n = 4), demonstrating that individual SCN cells are able to sustain sub-17 h circadian periods, and even with this short period, circuit-level mechanisms are able to maintain synchronization. In the complementary, extremely long-period condition, Fbxl3Afh/Afh SCNs treated with 100 μm KNK437 and also treated with TTX (Fig. 5D–F) exhibited desynchronization of the circuit (Rayleigh mean vector, 100 μm KNK437 alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p < 0.01, n = 4) and reduction of the coherence of individual cellular rhythms (100 μm KNK437 alone 0.13 vs with 1 μm TTX, 0.22 ± 0.06, p = 0.03, n = 4). As with the short-period condition, the overall cellular period was not significantly different from that of the SCN without TTX (100 μm KNK437 alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p = 0.31, n = 4), demonstrating that individual SCN cells are also able to sustain autonomous circadian periods of over 42 h.

SCN explant cultures express a high degree of precision and coherence between individual oscillators due to the strong coupling properties of the network. If, however, this coupling is disrupted (e.g., by dispersal), these oscillators become comparatively more imprecise (Herzog et al., 2004). To determine whether pushing the period to these extremes compromises the precision of the intact network, the range of periods revealed by individual oscillators (Fig. 5A,D) was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the SCN aggregate period (Fig. 5G). In the baseline condition, neither mutation produced a significant deviation from the relative period range of wild-type SCNs (data not shown; wild type vs CK1εTau/Tau vs Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 2.74 ± 0.38% vs 2.14 ± 0.15% vs 4.36 ± 1.00%; p = 0.08; n = 4/4/4). At the short-period extreme, the precision and coherence of the oscillation were maintained (CK1εTau/Tau baseline vs 100 μm picrotoxin, p = 0.52, n = 4), consistent with RAE (Fig. 1F) and Rayleigh analyses (Fig. 5C). Additionally, the long-period extreme also maintained precision and coherence at baseline levels (Fbxl3Afh/Afh baseline vs 100 μm KNK437, p = 0.12, n = 4), consistent with previous analyses (Figs. 1F, Fig. 5F). As expected, precision and coherence were lost when SCNs were treated with TTX at both period extremes (CK1εTau/Tau, 100 μm picrotoxin alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p < 0.01, n = 4; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 100 μm KNK437 alone vs with 1 μm TTX, p < 0.01, n = 4), illustrating the power of the network properties of the SCN when oscillating at these nonphysiological, extreme periods.

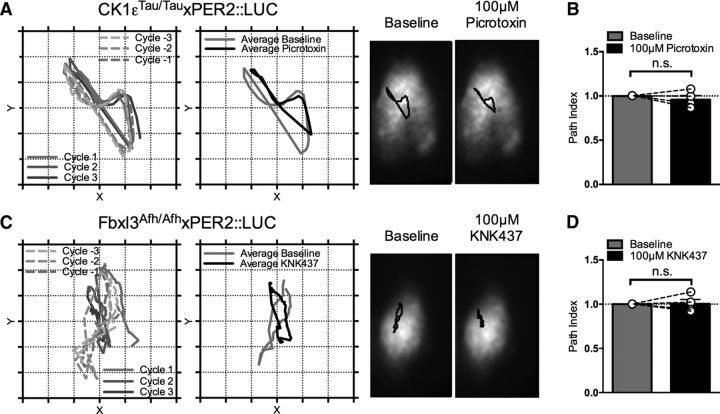

Temporal information in the SCN is not only encoded in time, but also through spatial waves of gene expression that flow across the network (Brancaccio et al., 2013). To determine whether pushing the SCN oscillation to extreme periods altered the informational content of the spatiotemporal wave, CoL analysis was applied to CCD recordings (Fig. 6A,C). The wave followed a highly repeatable orbit across the three cycles preceding pharmacological treatment and the first three cycles during pharmacological treatment. To assess whether the path length of the spatiotemporal wave differed between baseline and pharmacological treatment, a path index was calculated (Fig. 6B,D). This remained unaffected by pushing the SCN to extremely short (Fig. 6B; CK1εTau/Tau treated with 100 μm picrotoxin, baseline path index vs treatment path index, p = 0.47, n = 4) or extremely long periods (Fig. 6D; Fbxl3Afh/Afh treated with 100 μm KNK437, baseline path index vs treatment path index, p = 0.92, n = 4). Thus, single-cell analysis of the network properties of the SCN under extreme periods indicates that the effects on PER2::LUC bioluminescent waveform are dependent solely on the state of the internal oscillator, not circuit-based rearrangements. These results also prove that the isolated SCN is a remarkable biological oscillator that can reversibly maintain coherent rhythms even when pushed well outside the physiological period range.

Figure 6.

Network waveform properties of the SCN are unaffected by pushing period to short or long extremes. A–D, CoL analysis of CK1εTau/Tau × PER2::LUC treated with 100 μm picrotoxin (A, B) and Fbxl3Afh/Afh × PER2::LUC treated with 100 μm KNK437 (C, D). A, Left, Representative path vectors of center of luminescence across the slice displaying individual paths for three cycles before (dashed lines, graded gray) and during 100 μm picrotoxin application (solid lines, graded gray) and corresponding mean paths (right) showing baseline (gray) overlaid with 100 μm picrotoxin (black). Right, Representative single images of one SCN overlaid with mean path vectors (black) for baseline (left) and 100 μm picrotoxin (right). B, Summary data showing mean path index for baseline (gray) and 100 μm picrotoxin (black). Individual values are shown as hollow circles linked by dashed lines. C, Left, Representative path vectors of center of luminescence across the slice displaying individual paths for three cycles before (dashed lines, graded gray) and during 100 μm KNK437 application (solid lines, graded gray) and corresponding mean paths (right) showing baseline (gray) overlaid with 100 μm KNK437 (black). Right, Representative single images of one nucleus overlaid with mean path vectors (black) for baseline (left) and 100 μm KNK437 (right). D, Summary data showing mean path index for baseline (gray) and 100 μm KNK437 (black). Individual values are shown as hollow circles linked by dashed lines. Bars indicate mean ± SEM. n values are as detailed in text.

Discussion

In forcing the SCN to oscillate at extreme periods, we hypothesized three possible outcomes: (1) the network contains sufficient temporal elasticity to sustain extreme period oscillations; (2) the network is unable to sustain the oscillation and the slice becomes asynchronous, but cellular clock function is elastic and extreme cellular periods are retained; 3) the molecular oscillator is unable to sustain the oscillation and the slice becomes completely arrhythmic. Combined pharmacological and genetic manipulation of the SCN revealed that this structure forms a remarkable oscillator capable of maintaining coherent circadian rhythms of gene expression over an interval of between ca. 17 and 42 h. In addition, not only are these oscillations coherently maintained at the level of the aggregate signal, but they are also maintained at the cell-autonomous and spatiotemporal network levels as well as being fully reversible. These experiments demonstrate that even when faced with the need to adapt to wildly inappropriate periods, the SCN can maintain oscillations at every level of timekeeping (Brancaccio et al., 2013; Brancaccio et al., 2014); i.e., the cell-autonomous clock and the network contain sufficient temporal elasticity to maintain extreme period oscillations.

For context, in a competent wild-type SCN explant, the periods expressed by individual oscillators range from 24.51 ± 0.11 to 25.18 ± 0.13 h (n = 4; data not shown), an effective intra-SCN period range of <1 h. Between individual competent wild-type SCN explants, the period range of the aggregate signal is between 24.03 ± 0.07 and 25.26 ± 0.19 h (calculated from baseline data; Fig. 1), an effective inter-SCN period range of ∼1.5 h. These relatively small period ranges are imposed by tight interneuronal communication between oscillators (Yamaguchi et al., 2003). In other preparations that lack this degree of coupling between oscillators, the period range extends: for example, dissociated SCN neurons express periods between ∼22 and 26 h (Herzog et al., 2004), while fibroblasts oscillate between 22 and 30 h (Welsh et al., 2004), effective period ranges of 4–8 h. None of these preparations, however, approach the ranges reported here either within (CK1εTau/Tau, 12.6 h; wild-type, 12.8 h; Fbxl3Afh/Afh, 21.7 h) or between (∼25 h) genotypes, and, indeed, in a functional and coherent SCN network, this range is unprecedented.

The extreme period manipulations allowed us to reveal that the circadian oscillation of gene expression contains cryptic information. Our method of analyzing the waveform (Fig. 2) shows that the clock likely functions as a set of distinct stages, similarly to the cell cycle, with checkpoints and thresholds that need to be satisfied for the cycle to progress. This arrangement of clock progression has been hinted at before, where the clock moves through distinct transcriptional phases (Koike et al., 2012), although these phases refer to circadian output rather than direct progression of the clock per se. The FDA gives a parameter to clock analysis additional to phase, amplitude, and period of oscillations. The value of this analysis of waveform was revealed by treatment of the wild-type clock with the CK1ε inhibitor PF-4800567 (Fig. 4), a treatment previously identified as ineffective (Meng et al., 2010), but the FDA revealed a subtle effect in the second half of the circadian cycle. This indicated that the CK1ε isoform activity is most sensitive to pharmacological manipulation during the interval at which PER2 degradation occurs, consistent with the previously proposed role of CK1ε (Lowrey et al., 2000; Meng et al., 2008; Maywood et al., 2014).

Aside from revealing phase ordering of the circadian oscillation of gene expression, these experiments show that there is a strong interaction between genetics and pharmacology to different degrees across phases. It is apparent from FDA-S analysis that pharmacological manipulation of period exploits the same phase sensitivities regardless of genotype, but the magnitude of these phase sensitivities depends on genotype. In this way, FDA-S provides a useful insight into critical phases of the oscillation where a genetic mutation either sensitizes or protects against pharmacological manipulation, revealing pharmacologically specific phase patterning of the oscillation. Mechanistically, this is obvious when looking at the CK1εTau/Tau and wild-type slices treated with the CK1ε specific inhibitor PF-4800567, where specific inhibition of CK1ε highlights a significant genotype by pharmacology interaction over the first three quarters of the cycle that is attenuated toward the end of the cycle compared to the wild-type condition. This indicates critical internal phases where CK1ε alters period length in the CK1εTau/Tau mutation through inappropriately phased activity.

These analyses have been applied to the PER2::LUC waveform, which reports levels of the PER2 protein and therefore acts as a translational reporter (Yoo et al., 2004). In this way, the FDA only reports changes in PER2 dynamics and does not report causality. The changes here are likely driven by direct perturbation of other axes of the circadian oscillation that manifest as changes to the waveform of the PER2::LUC reporter. These range from direct perturbation of the PER2::LUC reporter through CK1 manipulation (CK1εTau/Tau, PF-670462, and PF-4800567) or through indirect perturbation of the PER2::LUC reporter through the CRY-mediated axis of timekeeping (Fbxl3Afh/Afh). Alternative approaches have used other circadian reporters, for example [Ca 2+]i imaging (Brancaccio et al., 2013) or transcriptional luciferase reporters (Maywood et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2015). Applying these analyses to different reporters may provide more insight into the phase arrangement of the circadian oscillation and how these different axes are interwoven. It is likely that the phase arrangement of such reporters differs from PER2::LUC, as some of these reporters have very obvious waveform differences, e.g., the narrow peak and wide trough of [Ca2+]i and AT-luciferase reporters (Brancaccio et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2015). Analysis of the waveform, for example, reveals that the peak rate of PER2 accumulation occurs between approximately circadian time 6 and circadian time 7.2 (normalized period, 0.25–0.3; Fig. 2). This coincides with the previously established peaks of calcium (Brancaccio et al., 2013) and spontaneous firing rate (Atkinson et al., 2011; Colwell, 2011). This is consistent with cAMP/Ca2+-response elements in the promoter of Per genes (Obrietan et al., 1999; Tischkau et al., 2003; O'Neill and Reddy, 2012) and illustrates one of the ways that this sort of analysis of gene expression dynamics can be used to further understand how different axes of timekeeping interact. Additionally, combination of FDA with real-time gene expression imaging in various tissues of freely moving animals (Ono et al., 2015a;b; Hamada et al., 2016) could allow pharmacologically sensitive phases of the circadian waveform to be aligned with behavioral data.

Finally, the circadian oscillator in the SCN provides a valuable natural tool to study the function of biological oscillators at both the cell-autonomous and network levels, and for this reason it has been the focus of mathematical modeling to explain these processes (Fuhr et al., 2015). Although these models have been used to great effect in combination with experimental data to study other properties of the SCN, such as intercellular coupling (DeWoskin et al., 2015; Myung et al., 2015) and phase entrainment (Bordyugov et al., 2015), few have modeled different period scales outside of 24 h. In this investigation, we present data from nine different genotype–pharmacology combinations that provide data on nine different period conditions that the SCN is able to sustain, and which reveal differential kinetics due to genotype–pharmacology interactions. Although these conditions are well outside the physiological range that the SCN would need to sustain, they are a product of SCN timekeeping in response to specific perturbations, and therefore represent behaviors of the SCN that bona fide models should be able to interrogate, replicate, and explain.

Furthermore, many biological processes exhibit oscillatory behavior on a broad range of timescales, for example, hormone cycles, dynamic calcium oscillations, and metabolic processes (Kim et al., 2010). Extending the analysis of waveforms beyond the circadian system may reveal underlying mechanisms of regulation to these oscillations. This could be especially interesting in considering how spontaneous slow-wave calcium oscillations propagate across the whole brain, what their kinetics are, and how oscillations arising from different brain areas interact at the phase-specific level. Measurements of such types of oscillation have not only been limited to normal function (Stroh et al., 2013), but have proved useful in developing an understanding of a range of different neuronal states, from neuronal maturation during development (Garaschuk et al., 2000) to disruption of long-range signals during neurodegeneration (Busche et al., 2015). Complementing these imaging tools with measurements of the kinetics of the calcium signal through circadian time could provide important information as to how networks interact across the whole brain and how these interactions are disrupted during pathogenesis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by UK Medical Research Council Grant MC_U105170643. We thank the biomedical staff at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Ares facilities for excellent technical support.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed.

References

- Atkinson SE, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Wozny C, Colwell CS, Hastings MH, Williams SR. Cyclic AMP signaling control of action potential firing rate and molecular circadian pacemaking in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms. 2011;26:210–220. doi: 10.1177/0748730411402810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordyugov G, Abraham U, Granada A, Rose P, Imkeller K, Kramer A, Herzel H. Tuning the phase of circadian entrainment. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12:20150282. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio M, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Loudon AS, Hastings MH. A Gq-Ca2+ axis controls circuit-level encoding of circadian time in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuron. 2013;78:714–728. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio M, Enoki R, Mazuski CN, Jones J, Evans JA, Azzi A. Network-mediated encoding of circadian time: the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) from genes to neurons to circuits, and back. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15192–15199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3233-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr ED, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS. Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators. Science. 2010;330:379–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1195262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, Kekuš M, Adelsberger H, Noda T, Förstl H, Nelken I, Konnerth A. Rescue of long-range circuit dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1623–1630. doi: 10.1038/nn.4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS. Linking neural activity and molecular oscillations in the SCN. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:553–569. doi: 10.1038/nrn3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWoskin D, Myung J, Belle MD, Piggins HD, Takumi T, Forger DB. Distinct roles for GABA across multiple timescales in mammalian circadian timekeeping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E3911–E3919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420753112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorostkar MM, Dreosti E, Odermatt B, Lagnado L. Computational processing of optical measurements of neuronal and synaptic activity in networks. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;188:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman GM, Jr, Nakajima M, Ueda HR, Herzog ED. Picrotoxin dramatically speeds the mammalian circadian clock independent of Cys-loop receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:103–108. doi: 10.1152/jn.00220.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr L, Abreu M, Pett P, Relógio A. Circadian systems biology: when time matters. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2015;13:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Linn J, Eilers J, Konnerth A. Large-scale oscillatory calcium waves in the immature cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:452–459. doi: 10.1038/74823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]