Abstract

Aryliodonium salts have become precursors of choice for the synthesis of 18F-labelled tracers for nuclear imaging. However little is known on the reactivity of these precursors with heavy halogenides, i.e. radioiodide and astatide at the radiotracer scale. Herein, we report the first comparative study of radiohalogenation of aryliodonium salts with [125I]-iodide and [211At]-astatide. Initial experiments on a model compound highlight a higher reactivity of astatide compared to iodide that could not be anticipated from the trends previously observed within the halogen series. Kinetic studies indicate a significant difference in activation energy (Ea = 23.5 and 17.1 kcal/mol with 125I− and 211At−, respectively). Quantum chemical calculations support the hypothesis of a monomeric iodonium-astatide intermediate whereas radio-iodination occurs in a dimeric environment. The good to excellent regioselectivity of halogenation and high yields achieved with diversely substituted aryliodonium salts indicates that this class of compounds is a promising alternative to the stannane chemistry currently used for radiohalogen labeling of tracers in nuclear medicine.

Keywords: Astatine, Radioiodine, Diaryliodonium salts, Nucleophilic Substitution, Radiopharmaceuticals

Graphical abstract

Radiohalogenation of diaryiodonium salts has been investigated and a significantly higher reactivity of astatide has been observed. Regioselectivity and reaction kinetics can be controlled by varying the nature of substituents. The high reactivity of these precursors makes them an attractive alternative to the conventional arylstannane chemistry for radiolabeling with iodine and astatine.

Introduction

Aryliodonium salts are attractive precursors for arylation of nucleophiles thanks to their low toxicity, the high regioselectivity they confer and the mild reaction conditions they require compared to conventional methods.[1,2] Halogens were amongst the first nucleophiles to be closely investigated for the nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) of aryliodonium salts more than 50 years ago,[3,4] and they are still considered for new methodologies in conventional organic synthesis.[5] Yet, it is only recently that applications related to halogenation with these precursors have been developed, especially in the field of radiochemistry with the radiolabeling of arenes with fluorine-18 for positron emission tomography (PET),[6–9] and improved preparation of important 18F-labeled radiotracer such as [18F]flumazenil[10] or [18F]mGlu5,[11] both for brain imaging.

In contrast to 18F, the other halogens have received limited attention for use of this reaction with aryliodonium salts at the radiotracer level. For instance, only one study to date has been reported on the reactivity of radiochloride[12], or with radioiodide in a patent[13] and to our knowledge, no reports exist regarding the reactivity of radioactive bromide, and astatide. Yet, a number of radioisotopes of the two heaviest halogens play important roles in nuclear medicine (123I, 124I, 125I, 131I and 211At as the most relevant radionuclides for use in imaging and/or therapy).[14] Many of the radioiodinated and astatinated compounds of interest are aromatic. They are generally obtained by conventional methods such as SNAr by halogen exchange, or electrophilic approaches such as halodemetallation or direct substitution.[15,16] However, these reactions are often associated with issues related to low radiochemical yields (RCYs), low specific activity, or concerns about the toxicity of the precursors and side products when considering human use. Consequently, the development of novel methodologies to improve the radiolabeling of arenes with heavy halogens remains an active area of research.[17,18]

Compared to iodine, the chemistry of astatine remains largely unexplored despite more than 70 years since the discovery of this element.[19] Its chemical behavior is not well understood and can differ significantly from the trends observed with the other halogens. Good reasons exist for this deficiency and are primarily due to the fact that no stable isotope exists, (the most stable, 210At has a T1/2 = 8.1 h), making difficult the characterization of species using conventional chemical and spectroscopic methods. For instance, the first ionization potential of At was only very recently determined accurately by using laser ionization spectroscopy, allowing refinement of previous estimations.[20] Nonetheless, despite noticeable divergences between iodine and astatine chemical behaviors, most of the organic reactions applicable to iodine such as electrophilic and nucleophilic substitutions has migrated to being performed with astatine. This partial understanding of astatine chemistry has successfully allowed the preparation of various molecules of biological interest and has led to a number of pre-clinical and clinical trials which demonstrated over the last 20 years the high potential of the 211At isotope (T1/2 = 7.2 h) for the treatment of cancers by targeted α-particle therapy.[16,21,22]

Latest advances in astatination methodologies show that electrophilic substitution of arylstannane remains the preferred method because of the RCYs generally obtained under smooth conditions.[23,24] However, since astatine can potentially exist in several oxidation states (−I, +I, +III, +V and +VII), obtaining pure At+ for electrophilic reactions is difficult to control, and partial over-oxidation to unwanted species can be difficult to avoid. This difficulty is mostly due to the extremely high dilution of 211At (cyclotron produced and distilled from a bismuth target) available in solution (generally available at picomolar or sub-picomolar concentrations), with tiny traces of impurity being able to perturb its reactivity and lead to side reactions and inconsistent reaction yields.[25] Additionally, it was shown that the +I oxidation state was not stable over time due to the inherent radiation arising from the decay of 211At to which it is exposed in solution, leading progressively to changes in its oxidation state, suggested by Pozzi et al to be At−.[26]

In contrast, formation of astatine as pure At− in reducing media is considerably easier since only one reduced species of the halogen exists.[27] This is why it appears necessary to have access to alternative methods of astatination that involve preferably the use of At−. Complementary to this status, the SNAr of aryliodonium salts appears to be an interesting alternative to explore.

In this study, we aimed to probe the comparative reactivity of iodide and astatide towards aryliodonium salts. 125I− and 211At− were investigated in parallel and their reactivity compared, with the additional purpose of expanding the understanding of the enigmatic chemistry of the heaviest of the halogens. We unveiled an unexpectedly higher reactivity of astatide over iodide that nucleophilicity difference alone cannot explain, but which involves two possible intermediates as supported by quantum chemical calculations.

Results and Discussion

Reaction parameters

Starting from the model compound bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium tosylate (Scheme 1a), influence of essential parameters were investigated, by adaptation from radiofluorination of aryliodonium.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of radioiodination and astatination of bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium tosylate (a), and formation of [211At]-4-tert-butylastatobenzene using the conventional astatodestannylation approach (b).

DMF is generally the preferred solvent for radiofluorination, although the use of acetonitrile (ACN) is also largely reported. This choice is dictated by the necessity of an aprotic polar solvent to perform the SNAr reaction. The reactivity of the fluoride ion being dramatically reduced in the presence of water,[28] it is usually necessary to perform the reaction in anhydrous media to obtain satisfactory radiochemical yields, a parameter that requires additional drying steps of the radionuclide.

In contrast, the nucleophilicity of the larger halogenides iodide and astatide was expected to be considerably less affected by the presence of polar protic solvents such as water due to the lower strength of hydrate shell of larger anions. Consequently, available aqueous [125I]NaI and [211At]NaAt were used without drying to avoid loss of activity during the process. Radiolabeling was performed by heating a 95% vol. mixture of a 5 mM iodonium salt in the desired solvent (ACN, DMF, MeOH or a 4:1 mixture of H2O/ACN), with 5% vol. of the aqueous radioiodide solution from 20 to 140 °C for 30 min. All reactions were analyzed chromatographically (HPLC), using the UV trace of 4-tert-butyliodobenzene as reference for comparison with the radioactive trace of the reaction solutions (Figure S1 in ESI). The retention time of the astatination product was nearly identical to 4-tert-butyliodobenzene, suggesting formation of the expected [211At]-4-tert-butylastatobenzene. To further confirm the identity of the astatinated product, [211At]-4-tert-butylastatobenzene was also prepared orthogonally by electrophilic astatodestannylation of (4-tert-butylphenyl)tributylstannane with 211At oxidized in the +I oxidation state by N-chlorosuccinimide (Scheme 1b), giving a congruent HPLC retention time (Figure S1).

Results of temperature and solvent impact studies show a clearly distinct difference in reactivity between iodide and astatide (Figure 1a–b). In the case of radioiodination, use of ACN was by far the more optimal choice as this solvent provided RCYs up to 93 % at 120 °C, whereas the other solvents resulted in RCYs below 25%, even up to 140 °C. In contrast, all solvent conditions gave high RCYs > 80 % for the astatination reaction, MeOH being even better than ACN whereas this solvent gave poor RCYs for radio-iodination.

Figure 1.

Influence of solvent and temperature on the radiochemical yield of [125I]-iodination a) and [211At]-astatination b) of bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium tosylate after 30 min reaction, and influence of counterion in ACN (c and d). Reactions were performed with a 5 mM iodonium salt concentration and 1.5 MBq of 125I− or 5 MBq 211At− (n = 3).

An important parameter that can dramatically influence the reactivity of iodonium salts is the nature of the counter-ion. In radiofluorination reactions, sulfonates have been generally preferred since they are good leaving groups and are also inert as compared to halogenides which are able to react with the iodonium by thermal decomposition. We chose to study the influence of the counterion for radioiodination and astatination using the same symmetric iodonium as above associated to sulfonates (tosylate and triflate) or halogenides (chloride and bromide). Radioiodination performed at 90 °C indicated a significantly higher kinetic of reaction with sulfonate salts with RCYs ≈ 70% after 45 min compared to the halogenide salts which gave RCYs ≈ 45 % (Figure 1c). In the case of astatination, the same reactivity sequence was observed, but with a smaller gap between the counter-ion types and with excellent reactivity. For instance, the kinetic was too fast at 90 °C to distinguish differences between anions, with all iodonium salts giving RCYs > 95 % within less than 10 min. When performing the reaction at a lower temperature (65 °C) the sequence OTs ≈ OTf > Cl > Br was observed with all compounds giving RCYs > 50 % after 15 min and nearly quantitative RCYs with all counterions by 45 min (Figure 1d).

Overall, this preliminary study guided us to the selection of ACN as the preferred solvent to continue the comparative study between astatide and iodide, with tosylate as counterion.

Influence of the substitution pattern of unsymmetrical iodonium salts

To demonstrate the potential of this reaction, we investigated the reactivity of unsymmetrically substituted iodonium salts. Unsymmetrical aryliodonium salts are generally preferred for radiohalogenation and other synthetic purposes since they are generally easier and more economical to synthesize, especially if complex aromatic structures are desired. In the context of radioiodination for biomedical use, it also appears essential to avoid the use of symmetrical iodonium salts since each aryliodonium molecule involved in the SNAr would release an unseparable cold equivalent of the radioiodinated compound of interest by reductive elimination and which would contribute to decreasing the specific activity.

The regioselectivity for SNAr towards non-equivalent aryl on diaryliodonium salts can be controlled by different factors, including the difference in electron density and steric hindrance between the two rings[29,30] or the presence of a catalyst such as copper salts.[31]

As a model, the electron rich 4-methoxyphenyl was chosen as directing group since it was shown to provide high regioselectivity toward the opposite aromatic ring with a large panel of electron-rich and electron deficient aryl counterpart in previous studies with 18F.[32,33] A similar preference of radioiodide and astatide for the most electron deficient ring was thus also expected. The 4-methoxyphenyl moiety was also chosen for its simplicity in this exploratory study although new directing groups have emerged such as the electron rich 2-thienyl[7] or highly sterically hindered cyclophane derivative.[34] A selection of variously substituted aryl-4-methoxyphenyl iodonium tosylates were consequently prepared (synthetic details in ESI) and investigated in radioiodination and astatination reactions. As expected, higher RCYs (RPhX + MeOPhX combined) were obtained when electron withdrawing groups were present with RCYs varying from 46 to 99% in a 30 min reaction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Influence of the substituent R on the RCY and the selectivity for target product of the radioiodination (n = 3).

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125I | 211At | |||

| R | RCY(I + II)a (%) | (I)/(II) ratio | RCY(I + II)a (%) | (I)/(II) ratio |

| H | 57 +/− 2 | 4.8 : 1 | 97 +/− 1 | 4.2 : 1 |

| 4-Me | 46 +/− 6 | 1.5 : 1 | 97 +/− 1 | 2 : 1 |

| 3-Me | 61 +/− 1 | 4.4 : 1 | 99 +/− 1 | 3.7 : 1 |

| 2-Me | 98 +/− 1 | 24 : 1 | 98 +/− 1 | 8.1 : 1 |

| 4-Cl | 68 +/− 2 | 10 : 1 | 98 +/− 1 | 5.3 : 1 |

| 4-CO2Et | 92 +/− 1 | 38 : 1 | 98 +/− 1 | 8.2 : 1 |

| 4-CN | 97 +/− 1 | > 50 : 1 | 99 +/− 1 | 16 : 1 |

| 3-NO2 | 67 +/− 4b | 28 : 1 | 99 +/− 1 | 24 : 1 |

| 4-NO2 | 90 +/− 2 | > 50 : 1 | 99 +/− 1 | 29 : 1 |

Decay corrected.

Presence decomposition products

In the case of astatination, the reactivity was so high that RCYs were quantitative with all substituents under these reaction conditions. The regioselectivity also clearly correlated with the electronic effects with high selectivity towards the formation of the product of interest (RPhX) when R substituents were the most electron-withdrawing. Additionally, the effect of steric hindrance was evaluated when R was a methyl group in ortho position. Similarly to what is usually observed in fluorination reactions, halogenation was favored on the ortho-substituted moiety in both radio-iodination and astatination, which can be explained by the transition states formed as demonstrated in previous studies.[8] It is noteworthy that regioselectivity was higher for iodination than for astatination especially with stronger electron withdrawing substituents. In order to rationalize the observed impact of the substituents a kinetic study was performed. The reaction was pseudo-first order considering the concentration variation of iodonium salt in large excess was negligible during the reaction course (Table S1). Results were then plotted in a Hammet diagram using σ value for each substituent and their reaction kinetics ki (Figure 2). An excellent linear correlation between the Hammet constants and kinetics was obtained with both radiohalogenides. The reaction constants (ρ) values were in line with the significant difference in the influence of the substituents observed between iodination and astatination (ρ = 1.82 and 1.34, respectively) considering that the higher the ρ, the more the reaction is sensitive to the electronic effect of the substituent. A comparison of the regioselectivities for the SNAr of the lighter radiohalogenides (18F− and 38/39Cl−) described in literature on identical iodonium salts shows a globally decreasing regioselectivity with increasing halogenide size (Table S2).[12,28] Consequently, it can be foreseen from our observations that the design of unsymmetrical iodonium salts for radiohalogenation will require more optimization with heavier radiohalogens to obtain optimal regioselectivity and consequently high RCYs and specific activities, particularly when electron rich products are desired.

Figure 2.

Hammett diagram for the [125I]-iodination (at 90°C) and [211At]-astatination (at 65°C) of unsymmetrical iodonium tosylates in ACN (n = 3).

Thermochemical and quantum chemical studies

To better understand the gap in reactivity between the two halogens, we investigated the reaction further in terms of kinetics and thermodynamics. Using the experimental conditions determined above on the symmetric iodonium model, the kinetic constants of the radiohalogenation reactions were determined at various temperatures (Figure S2 in ESI). Kinetic constants ki’ differed significantly between the two halogens. For instance, astatination occurred nearly 50-fold faster than iodination at 80 °C (Table 2), illustrating the higher reactivity of astatide.

Table 2.

Pseudo-first order reaction rates of the 125I and 211At-substitution on bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium tosylate in ACN (n = 3).

| Temperature (°C) |

ki’ (min−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| 125I | 211At | |

| 45 | - | 0.0231 +/− 0.0030 |

| 50 | - | 0.0368 +/− 0.0015 |

| 55 | - | 0.0494 +/− 0.0038 |

| 60 | - | 0.0742 +/− 0.0072 |

| 65 | - | 0.0992 +/− 0.0097 |

| 70 | - | 0.1498 +/− 0.0109 |

| 75 | - | 0.2226 +/− 0.0349 |

| 80 | 0.0082 +/− 0.0011 | 0.3770 +/− 0.0281 |

| 82.5 | 0.0122 +/− 0.0009 | - |

| 85 | 0.0160 +/− 0.0047 | - |

| 90 | 0.0225 +/− 0.0015 | - |

| 95 | 0.0355 +/− 0.0021 | - |

| 100 | 0.0535 +/− 0.0040 | - |

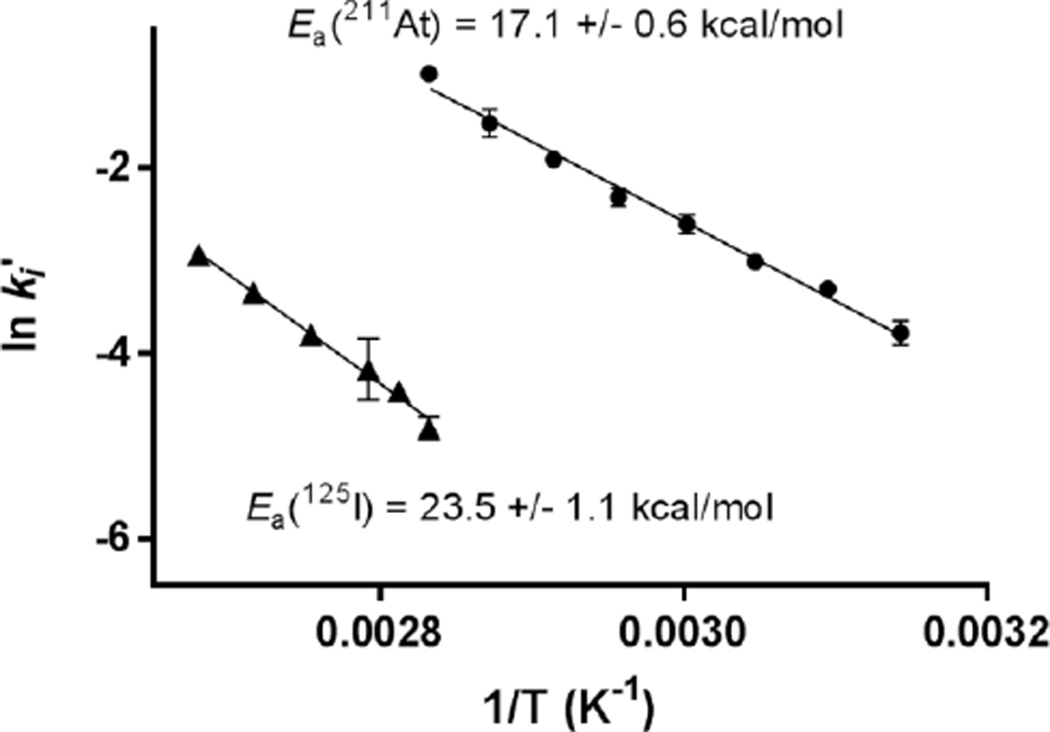

These kinetic constants were then used in the Arrhenius plot for determination of Ea (Figure 3). An Ea of 23.5 kcal/mol was obtained for the radioiodination whereas astatination occurred with a significantly lower Ea of 17.1 kcal/mol. The higher nucleophilicity of the astatide anion is not sufficient to explain the sharp increase in reactivity observed as compared to iodide. Whereas nucleophilicity increases in SNAr reactions with increasing size of halogenide, this was previously shown to have little influence on the Ea of halogenation of bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium (Cl− = 32.1, Br− = 32.2 and I− = 32.2 kcal/mol in DMF).[4]

Figure 3.

Arrhenius plot for the determination of Ea of the 125I (▲) and 211At-substitution (●) on bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium tosylate in ACN (n = 3)

Despite the lack of spectroscopic methods to probe possible mechanisms with astatine species at the radiotracer level, we tested several hypotheses to provide a rationale for the difference in reactivity. Several potential reaction courses reported in the literature have been considered and tested. This included the presence of metallic impurities in the astatine solution that could catalyze the reaction, as seen in the enhanced reactivity of fluoride on aryliodonium salts in the presence of copper salts.[9] However this possibility was excluded based on our observation that the outcome of the radioiodination reaction (kinetics and RCY) was unaffected when performed in the presence of astatine stock solution after the decay of the 211At activity. This test also excludes the sulfite ion as a potential cause of the reactivity change, Na2SO3 being otherwise absent in radioiodination solution, whereas astatine stock solution contains this reducing agent to produce the reactive 211At− species. The formation of a benzyne intermediate is a well known pathway of aryliodonium salt reactivity in the presence of a strong base. While the formation of benzyne in the presence of the basic fluoride anion has been reported,[35] iodide and astatide are such weak bases that they cannot be invoked as able to form such benzyne intermediates.

A more plausible explanation for the reactivity difference is the possibility of a radical mechanism, as previously given in a similar reaction with the astatination of diazonium salts.[36] On the other hand, radical pathways have also been pointed in reactions involving iodonium with nucleophiles such as 2-nitropropanate anion via a single electron transfer mechanism.[37] It has also been pointed out that under specific conditions, aryliodonium iodide decomposed in part via a radical pathway.[13,38] However, the hypothesis of a free radical reaction was ruled out by comparing the reaction rate in the presence of atmospheric oxygen (standard conditions of this study), in the absence of oxygen (solvent degassed under argon) and in the presence of a radical scavenger (TEMPO). In all three cases, reaction rates and products formed were essentially identical (Table S3). This indicates that if ever occurring, such a radical mechanism pathway is only a minor pathway in our reaction conditions to influence significantly the reaction at the radiotracer scale. Consequently, given the Hammet correlation obtained above, the reaction for both halogenides essentially follows a mechanism of the SNAr type.

On the other hand, iodonium salts are known to exist as dimers in the solid and gaseous phase, as well as in solution.[39,40] Similarly, we found that bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium iodide ((Ar2I)-I) exhibits a dimeric structure in the solid state (Figure S3).[41] Thus, we aimed to probe the influence of the monomeric and dimeric intermediates on the reaction by quantum chemical calculations. The X-Ray structure of iodonium iodide was used to construct the monomeric (Ar2I)-I, (Ar2I)-At, and (Ar2I)-OTs as well as the homodimeric [(Ar2I)-OTs]2. Given the extremely low concentrations of radioiodide (nanomolar to picomolar) or astatide (picomolar to femtomolar) involved in the reaction at radiotracer level, the probability for the iodonium radiohalogenide (125I or 211At) to form a homodimer is extremely low. Rather, given the much higher concentration of Ar2I-OTs in solution (5 mM), it would be as a heterodimer (Ar2I-X)(Ar2I-OTs) as shown in equation (1).

| (1) |

Energy calculations (see ESI) indeed indicate that (Ar2I)-OTs is more stable in its dimeric form by ΔG = −0.7 kcal/mol. Our calculations also indicate that the exchange of a tosylate in [(Ar2I)-OTs]2 with iodide from NaI or with astatide from NaAt to form the heterodimeric structures is thermochemically favorable by ΔG = −14.0 kcal/mol and −15.1 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure S4).

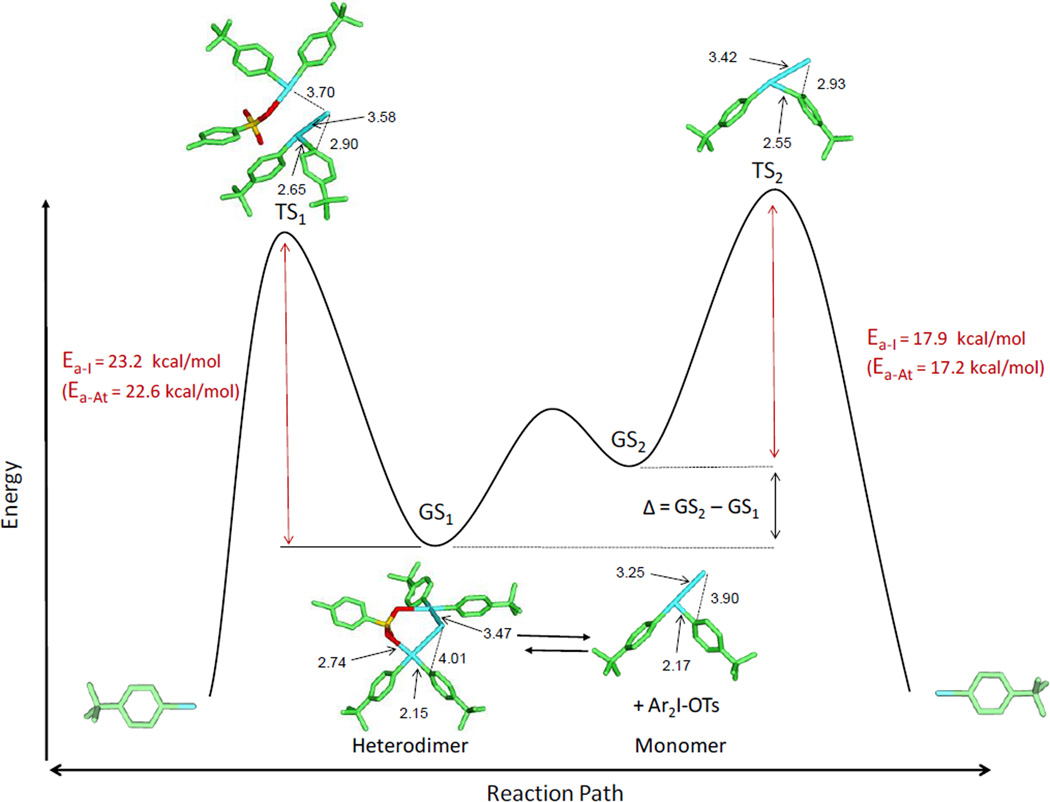

Ground states (GS) and transition states (TS) were then calculated taking into account two possible pathways: either from the heterodimer, or from the monomer in equilibrium (exemplified for iodination in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reaction diagram of radioiodination depicting both possible transition states (TS), either via a monomeric iodonium iodide or by a heterodimeric intermediate. The heterodimer exists in equilibrium with its monomers, and the interconversion between the two is likely much faster than the iodination. Accordingly, depending on the energy barrier of TS1 and TS2, the reaction follows either a dimeric or a monomeric pathway. The TS of the monomeric Ar2I-I is characterized by the sp3 hybridization of the Cipso due to the incoming iodide. The distance between the two atoms at the TS is considerably shorter (2.93 Å) as compared to that (3.90 Å) in the ground state (GS). I-Cipso distances of the heterodimer are 2.90 Å in the TS, and 4.01 Å in the GS, respectively. Note that the TS2 represents the sum of the Ea of the monomer and the dimerization energy (Δ), which is the energy difference between the monomers (GS2) and its dimer (GS1). Atoms are colored as follows: green, carbon; red, oxygen; yellow, sulfur; dark green, iodine. Hydrogen atoms are not shown. All distances are in Å. A similar diagram can be constructed for astatination. Ea-Ats are provided for comparison and optimized structures with bond length are available in Figure S5.

The calculated Ea, corresponding to the difference of the sum of the electronic energy and zero-point vibrational energy between the GS and the TS, is 17.9 kcal/mol for iodination and 17.2 kcal/mol for astatination from the monomeric complex, whereas it is 23.2 kcal/mol and 22.6 kcal/mol from the dimeric complex for iodination and astatination, respectively. The extra charge interaction provided by Ar2I-OTs is likely responsible for the increase of Ea in the dimer pathway. For example, the nucleophilic iodide in the GS1 has to overcome the charge attraction provided by the central iodine atom of Ar2I-OTs to form a bond with the Cipso. The good agreement between the calculated Ea for iodination via the heterodimer (23.2 kcal/mol) and the experimental Ea (23.5 kcal/mol) suggests that the radioiodination occurs in a dimeric environment. In contrast, the calculated Ea for astatination via the monomer (17.2 kcal/mol) agrees with the experimental Ea (17.1 kcal/mol) which indicates that the astatination likely occurs in a monomeric environment. It is noted that the calculated difference of Ea for iodination and astatination is only 0.6 to 0.7 kcal/mol in both monomeric and heterodimeric form, which suggests that the difference in nucleophilicity between astatide and iodide plays a minor role in the reaction. The proposed mechanism (Figure 4), another representation of the Curtin-Hammet principle,[42] further indicates that the relative stability of monomers over dimers modulates the energy barrier of halogenation in a monomer, which in turn dictates whether iodination or astatination occurs within a monomeric or a dimeric complex.

The ΔG for dimerization (−2.0 kcal/mol at 298.15K) in both cases calculated by subtracting the sum of the free energy of each monomer from that of the dimer favors the formation of the heterodimers. However, the contribution of translational and rotational entropy of each monomer to dimerization in the liquid phase is known to be much lower than in the gas phase due to solvent-restricted movement of monomers[43]. Accordingly, the above ΔG, including both translational and rotational entropy based on the ideal gas approximation, can be more negative than −2.0 kcal/mol. Therefore, this ΔG alone may not be a reliable marker for determining whether the reaction follows either a dimeric or a monomeric pathway.

In the case of astatination, it is likely that due to its higher polarizability, astatide forms a stronger complex than iodide with the iodonium, similarly to the reported case of diazonium which also exhibits greatly enhanced reactivity with astatide as compared to iodide.[36] The higher polarizability of astatide induces a higher delocalization of the charge from the halogenide to the iodonium compared to lighter halogens, leading to a tighter ion pair by virtue of electrostatic interactions. In this context, it can be expected that the extra charge interaction of Ar2I-OTs with astatide is considerably lower than with iodide, resulting in a thermodynamically less favorable heterodimeric structure. Further investigation will be necessary to corroborate this point.

Conclusions

In summary we have explored the reactivity of heavy halogenides towards aryliodonium salts at the radiotracer scale. We unveiled an unexpected and significantly higher reactivity of astatide as compared to the trend observed within other halogens. Quantum chemical calculations led us to propose that astatination occurs via the monomeric form of an iodonium complex whereas iodination occurs via a more stable heterodimeric iodonium intermediate. Overall, it appears that iodonium salts are a promising alternative class of precursor to organotin based chemistry for radioiodination and astatination. Iodonium salts achieved more consistent and nearly quantitative astatination RCYs in smooth conditions due to the use of the −I oxidation state which is simpler to control in organic media at the radiotracer level than the +I oxidation state needed for electrophilic substitutions. As expected, we observed that regioselectivity of SNAr of non-symmetrical diaryliodonium salts is governed by electronic and steric effects. However, the lower regioselectivity that is observed in iodination, and to a greater extent in astatination, as compared to the radiofluorinations described in literature, suggests that carefully designed diaryliodonium salts will be required for efficient synthesis and optimal specific activity of aryl radioiodide and arylastatide compounds, especially in the case of aryl substituted by electron donating groups. Ultimately, we anticipate that this radiolabeling approach will become a highly used tool for the radiolabeling of biomolecules with heavy radiohalogens with applications in nuclear imaging and targeted radiotherapy. Through the development of specifically designed iodonium salts, such efforts are underway in our laboratory.

Experimental Section

Radiochemistry

[125I]NaI was obtained commercially in 10−5 M NaOH solution with a volumic acitivity of 50 µCi/µL (1.85 MBq/µL) and was diluted 12 times in deionized water before use. 211At was produced using the 209Bi(α,2n)211At reaction by bombarding a disposable internal bismuth target with α-particles from the Cyclotron Corporation CS-30 cyclotron in the National Institutes of Health Positron Emission Tomography Department. 211At was recovered from the irradiated target in acetonitrile using the dry-distillation procedure described previously.[44] Before use, the 211At solution was diluted twice in a 10 mg/mL aqueous solution of Na2SO3, resulting in a 1:1 ACN/water solution of sodium astatide. Iodonium salts were obtained commercially, or synthesized as described in ESI.

Reaction of iodonium salts with [125I]-iodide and [211At]-astatide

To 950 nmol of iodonium salt in 190 µL of the selected solvent equilibrated at the appropriate temperature of reaction was added 10 µL (typically 1.5 MBq) of [125I]NaI or [211At]NaAt prepared as described above. At desired times, aliquots were withdrawn and deposited on a silica gel TLC plate and eluted with the appropriate solvent, and/or diluted in a 1/1 mixture of water/ACN and analyzed by reverse phase HPLC using the appropriate elution system. Retention indexes and elution systems used for all compounds of this study are given in ESI. Aromatic 125I and 211At species were identified by comparison of the retention index of authentic samples of the non-radioactive iodinated compound.

Astatination via electrophilic destannylation

To 20µL 2.5 mg/mL tributyl(4-tert-butylphenyl)-stannane in ACN/AcOH (99:1) was added 5 µL of 2 mg/mL N-chlorosuccinimide in ACN, followed by 75 µL of the 211At activity (5 MBq) in ACN. The solution was heated for 30 min at 60°C and after cooling down to room temperature, the solution was diluted with 100µL of water, and an aliquot was analyzed by HPLC using the same chromatographic system as described above.

Quantum Chemistry

The X-ray structure of Bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium iodide was used as a template to construct both the monomeric and hetero-dimeric structures of Ar2I+ complexed with iodide or astatide. Quantum chemical calculations were carried out with the density functional theory at the level of B3LYP with the small-core pseudopotentials[45] for the I and At atoms with the cc-pVDZ basis set for their 25 valence electrons together with the all electron cc-pVDZ basis set for the rest of the atoms. All calculations were carried out in the reaction field of ACN with the polarizable continuum model together with the UAKS parameters set as implemented in Gaussian 09 software[46]. For each TS, a single imaginary frequency was obtained. Coordinates of calculated structures are available in Table S4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and Center for Information Technology and in part by grants from the French National Agency for Research, called “Investissements d’Avenir” IRON Labex n° ANR-11-LABX-0018-01 and ArronaxPlus Equipex n°ANR-11-EQPX-0004. The quantum chemical study utilized PC/linux clusters at the center for Molecular Modeling of the National Institutes of Health (http://cit.nih.gov). Lawrence Szajek, NIH, CC is thanked for his cyclotron operations and irradiation of bismuth targets for the production of 211At. Pr Vanelle is thanked for the input on radical mechanism investigations.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.Merritt EA, Olofsson B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9052–9070. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhdankin VV, Stang PJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:5299–5358. doi: 10.1021/cr800332c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beringer FM, Geering EJ, Kuntz I, Mausner M. J Phys. Chem. 1956;60:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beringer FM, Mausner M. J Am. Chem. Soc. 1958;80:4535–4536. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu B, Miller WH, Neumann KD, Linstad EJ, DiMagno SG. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015;21:6394–6398. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tredwell M, Gouverneur V. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:11426–11437. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross TL, Ermert J, Hocke C, Coenen HH. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8018–8025. doi: 10.1021/ja066850h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun J-H, Lu S, Lee Y-S, Pike VW. J Org. Chem. 2010;75:3332–3338. doi: 10.1021/jo100361d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichiishi N, Brooks AF, Topczewski JJ, Rodnick ME, Sanford MS, Scott PJH. Org. Lett. 2014;16:3224–3227. doi: 10.1021/ol501243g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon BS, Kil HS, Park JH, Kim JS, Park J, Chi DY, Lee BC, Kim SE. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:8346–8355. doi: 10.1039/c1ob06277h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telu S, Chun J-H, Siméon FG, Lu S, Pike VW. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:6629–6638. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05555k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M-R, Kumata K, Takei M, Fukumura T, Suzuki K. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2008;66:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimagno S, Hu B. WO2015147950 (A2) Radioiodinated Compounds. 2015

- 14.Adam MJ, Wilbur DS. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:153–163. doi: 10.1039/b313872k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coenen HH, Moerlein SM, Stöcklin G. Radiochim. Acta. 1983;34:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guérard F, Gestin J-F, Brechbiel MW. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013;28:1–20. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cant AA, Champion S, Bhalla R, Pimlott SL, Sutherland A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:7829–7832. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan R, Sander K, Galante E, Rajkumar V, Badar A, Robson M, El-Emir E, Lythgoe MF, Pedley RB, Årstad E. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:703–709. doi: 10.1021/ja307926g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilbur DS. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:246–246. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothe S, Andreyev AN, Antalic S, Borschevsky A, Capponi L, Cocolios TE, De Witte H, Eliav E, Fedorov DV, Fedosseev VN, et al. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1835. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y-S, Brechbiel MW. Tumor Biol. 2012;33:573–590. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0286-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. Curr. Radiopharm. 2008;1:177–196. doi: 10.2174/1874471010801030177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajerison H, Faye D, Roumesy A, Louaisil N, Boeda F, Faivre-Chauvet A, Gestin J-F, Legoupy S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:2121–2126. doi: 10.1039/c5ob02459e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aneheim E, Gustafsson A, Albertsson P, Bäck T, Jensen H, Palm S, Svedhem S, Lindegren S. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016;27:688–697. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visser GW. Radiochim. Acta. 1989;47:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pozzi OR, Zalutsky MR. J Nucl. Med. 2007;48:1190–1196. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sergentu D-C, Teze D, Sabatié-Gogova A, Alliot C, Guo N, Bassal F, Silva ID, Deniaud D, Maurice R, Champion J, et al. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016;22:2964–2971. doi: 10.1002/chem.201504403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chun J-H, Telu S, Lu S, Pike VW. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:5094–5099. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40742j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill DE, Holland JP. Comp. Theor. Chem. 2015;1066:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malmgren J, Santoro S, Jalalian N, Himo F, Olofsson B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013;19:10334–10342. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichiishi N, Canty AJ, Yates BF, Sanford MS. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5134–5137. doi: 10.1021/ol4025716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chun J-H, Pike VW. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:9921–9923. doi: 10.1039/c2cc35005j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chun J-H, Pike VW. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:6300–6306. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41353e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B, Graskemper JW, Qin L, DiMagno SG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4079–4083. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitamura T, Yamane M, Inoue K, Todaka M, Fukatsu N, Meng Z, Fujiwara Y. J Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11674–11679. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer GJ, Roessler K, Stoecklin G. J Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:3121–3123. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh PR, Khanna RK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:5355–5358. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ermolenko MS, Budylin VA, Kost AN. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1978;14:752–754. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcock NW, Countryman RM. J Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1977:217–219. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y-S, Hodošček M, Chun J-H, Pike VW. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010;16:10418–10423. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CCDC-1452802 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data%5Frequest/cif

- 42.Seeman JI. Chem. Rev. 1983;83:83–134. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu YB, Privalov PL, Hodges RS. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1632–1642. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75817-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindegren S, Bäck T, Jensen HJ. Appl Rad Isot. 2001;55:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(01)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson KA, Figgen D, Goll E, Stoll H, Dolg M. J Chem. Phys. 2003;119:11113–11123. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch J, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, revision A.02. Wallingford CT: Gaussian Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.