Abstract

Biatractylolide was isolated from ethyl acetate extract of dried Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma root by multistep chromatographic processing. Structure of biatractylolide was confirmed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR. The IC50 on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was 6.5458 μg/mL when the control IC50 value of huperzine A was 0.0192 μg/mL. Molecular Docking Software (MOE) was used to discover molecular sites of action between biatractylolide and AChE protein by regular molecular docking approaches. Moreover, biatractylolide downregulated the expression of AChE of MEF and 293T cells in a dose-dependent manner. These results demonstrated that the molecular mechanisms of inhibitory activities of biatractylolide on AChE are not only through binding to AChE, but also via reducing AChE expression by inhibiting the activity of GSK3β.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disease, which is the most frequent and predominant cause of dementia in the elderly, provoking progressive cognitive decline, psychobehavior disturbances, memory loss, the presence of senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and the decrease in cholinergic transmission [1, 2]. Many risk factors have participated in AD pathogenesis, but studies have demonstrated that GSK3β played the most critical role in this disease conditions [3, 4]. Abnormal activity of GSK3β not only led to Aβ generation and aggregation [5], tau protein phosphorylation, and high mitochondrial dysfunction [6], but also upregulated the expression of AChE in AD [7]. Recently, two major hypotheses: the cholinergic hypothesis and the amyloid cascade hypothesis, have been proposed to elucidate the molecular mechanism of AD pathogenesis. In order to treat and prevent AD, most pharmacological research has focused on AChE inhibitors to alleviate cholinergic deficit and improve neurotransmission. AChE plays a significant role in the termination of nerve impulse transmission at the cholinergic synapses by rapid hydrolysis of acetylcholine (ACh). AChE inhibitors can increase the cholinergic transmission by blocking the degradation of ACh and are therefore considered to be a promising approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease [8]. The roots of Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma have been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine due to their antioxidative and preventive effects of AD. Biatractylolide is an active component existing in Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizome. This small molecule has a symmetrical structure which has a novel double sesquiterpene esters. Reference [9] reported that biatractylolide could slow down the isolated guinea pig right atrium heart rate and reduce shrinkage force. However, this effect could be offset by atropine, indicating that biatractylolide might inhibit cholinesterase effect. Our previous study showed that biatractylolide can significantly reduce the activity of AChE in mice brain and improve the syndrome of mouse dementia induced by aluminum trichloride [10]. However, the molecular mechanisms of biatractylolide on anti-AD remained unclear. In this study, extracted biatractylolide from Chinese traditional medicine Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizome was applied to explore its molecular mechanisms of inhibiting AChE, providing a theoretical basis for of its clinical application on anti-AD syndrome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Biatractylolide was isolated from ethyl acetate extract of dried Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma root by multistep chromatographic processing. Structure of biatractylolide was confirmed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR. Lithium chloride was purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-AChE antibody (H-134), anti-GSK3β (H-76) antibody, and GAPGH (FL-335) antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and were diluted by 1 : 1000 when used. Complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding full-length human AChE-S (hAChE-S) and human AChE-R (hAChE-R) cloned into the pL5CA expression vector were gifts from Dr. Hermona Soreq at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The correct sequences of all cDNA clones were verified by automated DNA sequencing analysis.

2.2. Extraction and Isolation

The air-dried Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma (15 kg) were extracted with EtOAc at room temperature for 7 days three times. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain a dark green extract (275 g). The extract was dissolved and partitioned between petroleum ether and ethyl acetate. The petroleum ether portion was subjected to a silica gel column and eluted with a petroleum ether–ethyl acetate gradient system (PE–EtOAc 20 : 1, 10 : 1, 10 : 2, 10 : 3). The portion of 10 : 1 was subjected to repeated column chromatography with silicagel (petroleum ether-acetone, 20 : 1 to 5 : 2) and further purification by preparative TLC to obtain biatractylolide (480 mg).

2.3. Molecular Docking Studies

We drew out biatractylolide dimensional structure by ChemDraw software and then imported structure into Chem3D, and biatractylolide molecules energy optimized by MM2 force field, saved as mol2 format; finally, biatractylolide molecules had the hydrogenation and energy optimization by MOE software. We searched three-dimensional structure of AChE targets from the protein database and then found the key of active amino acid residues for molecular docking into MOE software. We had analyzed the relationship between active amino acid residues and biatractylolide, predicted interaction between biatractylolide and AChE protein target, and elucidated chemical structural foundation of biatractylolide as AChE inhibitor.

2.4. Determination of AChE Inhibition Activities

AChE inhibitory activity was measured by using an assay described by Ellman et al. [11] along with the modifications described by Hostettmann et al. [12]. Briefly, the sample (20 µL) (biatractylolide was dissolved in DMSO and diluted with PBS to 12 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, 8 μg/mL, 6 μg/mL, 4 μg/mL, 3 μg/mL, 2 μg/mL, and 1 μg/mL; huperzine A was dissolved in methyl alcohol and diluted with PBS to 0.065 μg/mL, 0.050 μg/mL, 0.035 μg/mL, 0.025 μg/mL, 0.020 μg/mL, 0.015 μg/mL, 0.010 μg/mL, and 0.005 μg/mL), along with the buffer (140 µL) and 0.28 U/mL AChE (15 µL), and the mixture were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The time at which the first enzyme addition was performed was considered as time zero. After the 15 min incubation, 2 mM DTNB (10 µL) and 15 mM ATCI (10 µL) were added, and the final mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 402 nm by using a microplate reader (Synergy H4 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). A control mixture was prepared by using 20 µL of PBS instead of the biatractylolide sample, with all other procedures similar to those used in the case of the sample mixture. The percentage inhibition of enzyme activity was calculated by comparison with the negative control: % = [(A 0 − A 1)/A 0] × 100, where A 0 was the absorbance of the blank sample and A 1 was the absorbance of the sample. Tests were carried out in triplicate. The inhibition of the enzyme activity was expressed as IC50 (the concentration of the sample required to inhibit 50% of enzyme), which was calculated by a curve fitting analysis of the dose-effect relationship, used by OriginPro 9.0.

2.5. Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293T cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Sigma, Louis. MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA) and nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin. Cells were trypsinized and reseeded in culture plates one day before transfection. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. HEK293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 when cell confluency was 70%. Mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 15% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific) and 4 mM L-glutamine and nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen). Cells were trypsinized and reseeded in culture plates 1 day before transfection. Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine LTX and PlusTM reagent (Invitrogen) when cell confluency was 70% according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.6. Western Blotting

Cultured cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped off the plate, centrifuged at 1500 rpm, and cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Cell lysates (100 mg protein each) were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) electrophoresis and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked in TBST containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Blotted membranes were probed with their respective primary antibodies rotating at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed three times in TBST buffer and probed with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG or IRDye 800-conjugated Affinity Purified Anti-Mouse IgG, resp.) at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were then washed three times in TBST buffer and direct infrared fluorescence detection was performed with a Licor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System [13]

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and significant differences between treatment groups were determined using the unpaired Student's t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction and Separation

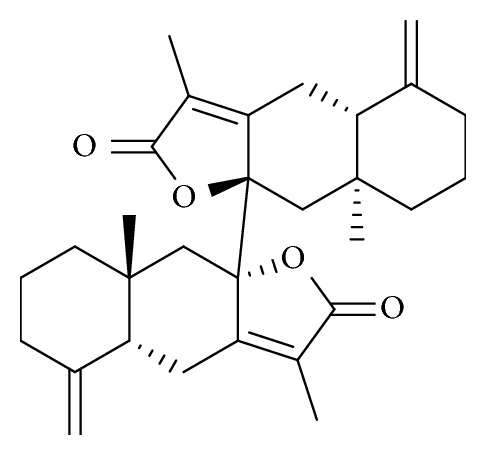

Biatractylolide was isolated from ethyl acetate extract of dried Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma root by multistep chromatographic processing. Chemical structure of biatractylolide was confirmed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR. The spectral data is in agreement with the literature [14] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of biatractylolide. Biatractylolide is a kind of internal symmetry double sesquiterpene novel ester compound.

3.2. Molecular Docking Studies

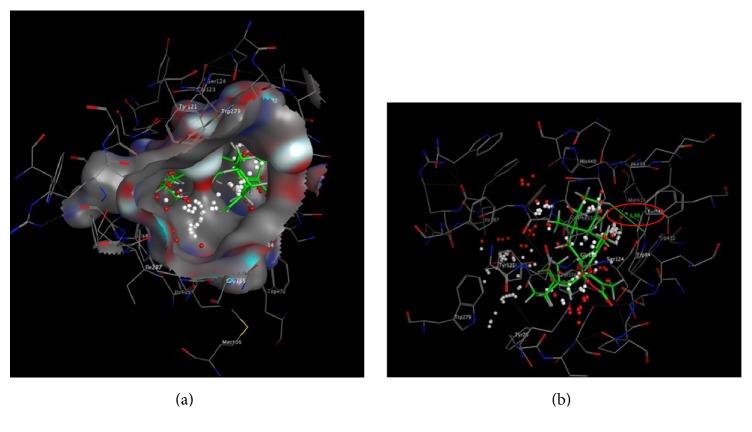

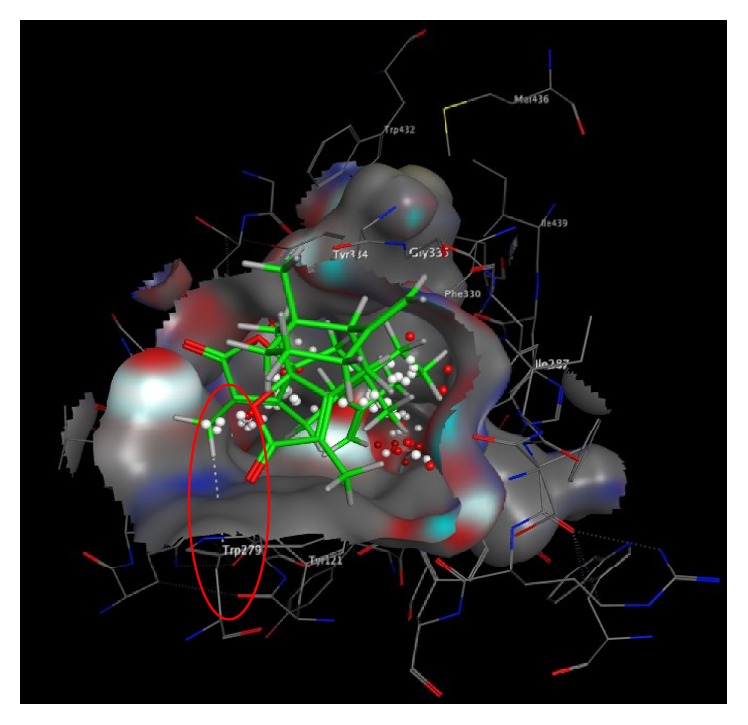

We found a number of important active amino acid residues on PAS and CAS activity center: PAS: Trp279, Tyr70, and Tyr334; CAS: Trp84, IIe439, IIe287, and Tyr121. MOE molecular docking showed that biatractylolide combined with AChE protein important active amino acid residues Trp279 (PAS active site) by H-π (3.31 Å) (see Figure 2). Biatractylolide entire molecule passed through the narrow “aromatic gorge” into the AChE protein activity pocket bottom (Figure 3(a)). Biatractylolide also combined with Trp84 (CAS active site amino acid residues) by H-π (3.88 Å) (Figure 3(b)). The results indicated that biatractylolide could be combined with AChE protein by a dual target binding. However, it bound the CAS active site with more stabilities.

Figure 2.

Molecular docking between biatractylolide and PAS active site. The figure showed biatractylolide combined with AChE protein important active amino acid residues Trp279 (PAS active site) by H-π (3.31 Å).

Figure 3.

Molecular docking between biatractylolide and CAS active site. (a) showed biatractylolide entire molecule passed through the narrow “aromatic gorge” into the AChE protein activity pocket bottom. (b) showed biatractylolide also combined with Trp84 (CAS active site amino acid residues) by H-π (3.88 Å).

Biatractylolide molecule is a large molecule with steric hindrance. It has much chiral carbon, and it has no conjugate rigid structure such as aromatic ring, so biatractylolide molecular after conformation twisting could smoothly pass through the AChE aromatic gorge into interior of the protein activity pocket and then it had effect with Trp84 and Trp279, two active amino acid residues, which may be the reason it has AChE inhibition.

3.3. Determination of AChE Inhibitory Activities

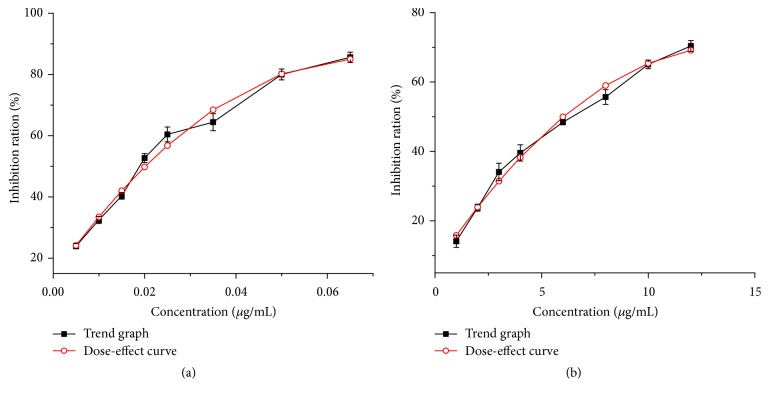

In our ongoing search for biatractylolide AChE inhibitors, it was found that biatractylolide mildly inhibited the AChE activity with an IC50 value of 6.5458 μg/mL (see Figure 4) when huperzine A showed AChE inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 0.0192 μg/mL.

Figure 4.

Different concentrations of huperzine A and biatractylolide corresponding AChE inhibition. The curve fitting of huperzine A was y = −15411.47x 2 + 2092.92x + 14.09 (R 2 = 0.9824, IC50 = 0.0192 μg/mL = 0.0793 μM). The curve fitting of biatractylolide was y = −0.33x 2 + 9.14x + 6.99 (R 2 = 0.9874, IC50 = 6.5458 μg/mL = 14.1685 μM).

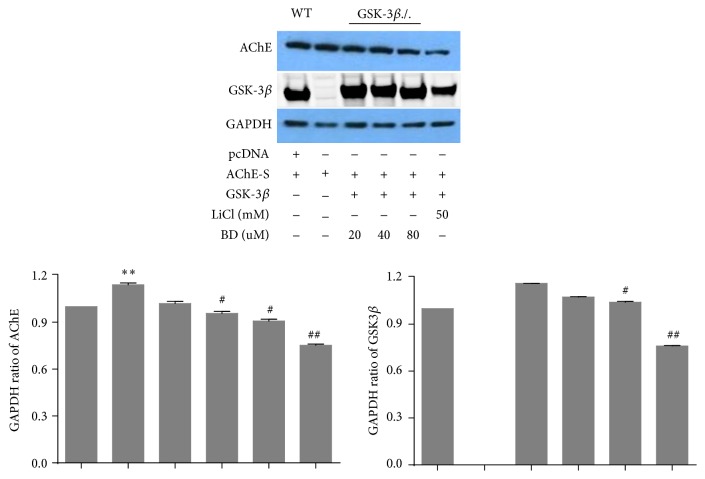

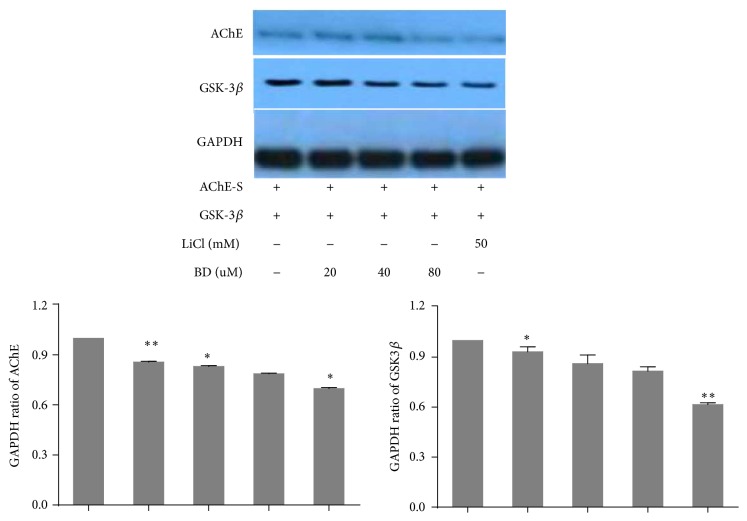

3.4. AChE Protein Characterization

Figure 5 showed wild type MEF cells which was transfected with the AChE-S expressed AChE protein, and so did knocked out GSK3β gene MEF cells, indicating the success of the transfection. We added different concentrations of biatractylolide and 50 mM LiCl (a kind of specific inhibitor for GSK3β which is reported to stop the expression of AChE-S in apoptosis process [3] by inhibiting GSK3β) after MEF cells which knocked out GSK3β transfected heterologous gene GSK3β and AChE-S. The result showed that AChE expression gradually reduced with increased biatractylolide concentrations. Moreover, AChE had low expression after adding LiCl. However, the expression levels of AChE are still not high after being transfected with AChE-S in MEF cells. In order to further confirm our results, we chose 293T cell whose transfection efficiency is higher than MEF cells; we transfected AChE-S and GSK3β into 293T cells directly (Figure 6). As the biatractylolide concentration increased, we observed that biatractylolide Control Group had high expression of GSK3β and AChE. However, the expression of AChE was gradually reduced, so we hypothesized that biatractylolide downregulated expression levels of AChE by inhibiting GSK3β.

Figure 5.

AChE protein characterization of MEF. The figure represents western blotting of AChE and GSK-3β after MEF cell lines were treated by BD (biatractylolide) and LiCl. GAPDH was included as a loading control. The ratio of different proteins to GAPDH was calculated by the band density of western blots of each cell line using Image J software. # p < 0.05 versus Control Group, ## p < 0.01 versus Control Group, ∗ p < 0.05 versus WT Group, and ∗∗ p < 0.01 versus WT Group.

Figure 6.

AChE protein characterization of 293T. The figure represents western blotting of AChE and GSK-3β after MEF cell lines were treated by BD (biatractylolide) and LiCl. GAPDH was included as a loading control. The ratio of different proteins to GAPDH was calculated by the band density of western blots of each cell line using Image J software. ∗ p < 0.05 versus Control Group; ∗∗ p < 0.01 versus Control Group.

The incidence of AD is increasing with the acceleration of global ageing. It is estimated that the world will have at least 48 million AD patients in 2024, while China is one of the countries most affected by aging. Thus, the development of new anti-AD drugs is of great significance.

AChE inhibitors combined with AChE to inhibit the hydrolysis of AChE activity, increasing ACh content between synapses in the brain, and then improving the cognitive ability of patients with AD. Currently most of available anti-AD drugs are AChE inhibitors, such as donepezil and rivastigmine, but they have severe side effects which limited the clinical application [15]. The fact that naturally occurring compounds from plants are considered to be a potential source of new inhibitors has led to the discovery of an important number of secondary metabolites and plant extracts with the ability of inhibiting the enzyme AChE. Sepsova et al. [16] separated N-methyl shiva alkali from lotus which was a noncompetitive inhibitor of AChE with an IC50 value of 1.5 μg/mL. Barak et al. [17] obtained six berberine compounds from the Chinese traditional medicine Coptis which had the function of the nerve protection and improvement of cognition and confirmed strong AChE inhibitory activity with an IC50 value 1.44~1.80 μg/mL. Berg et al. [18] isolated Macluraxanthone from Maclura pomifera which was a noncompetitive AChE inhibitor with IC50 value 8.47 μg/mL. All these results have shown a strong prospect using plant sources to extract and develop anti-AD drugs.

Molecular docking is widely used in the development of AChE inhibitors [19]. Amino acid residues Trp 279, Tyr 70, and Tyr 334 are negatively charged and located in PAS [20, 21]. Compounds profenamine, BW284C5, and fasciculin could have effects with PAS active site [22]. The occupation and mutation of Trp279 site seriously affected the affinity of enzyme and substrate, and the enzyme activity. Our molecular docking studies showed biatractylolide to interact with Trp279 via H-π (3.31 Å) role, indicating that biatractylolide could affect enzyme activity by occupying the site.

Trp84 located in CAS catalytic center; study has shown that ACh quaternary ammonia nitrogen atoms could have effect with Trp84 ring benzene on the amino acid residues, and the distance between them is 4.8 Å [23]. Biatractylolide lactone ring methyl hydrogen atom interacts with Trp84 ring benzene on the amino acid residues, so biatractylolide is a two-site AChE inhibitor.

The apoptosis rate of nerve cells in AD patients' brains is higher and so is AChE activity in pathologic region. In addition, AChE facilitates the poisonousness precipitation of Aβ sample. Among the three AChE subtypes, only AChE-S is capable of hydrolyzing AChE [24]. Transgenic mouse overexpressing AChE-S bears apparently more dynamic activity in catalyzing the hydrolyzation of ACh. The obvious increase in expressing caspase-3 and apoptotic protein in nerve cells justifies that the overexpression of AChE-S facilitates the apoptosis of nerve cells [25]. Studies [26] have showed that transfecting N-terminal AChE-S to cortical neurons can lead to apoptosis, mitochondria damage, overexpression of caspase-3 and GSK3β activation, and accelerating highly phosphorylation of tau. Moreover, by inhibiting GSK3β and having apoptosis inhibitory protein Bcl2 overexpressed, survival rate of nerve cells improves. These facts demonstrated that AChE-S could be used as a target spot in developing anti-AD drugs. Our previous study proved that biatractylolide cures AD model rats. In this study, we are interested in investigating the molecular mechanism underlying inhibition of AChE expression. These results have showed that biatractylolide inhibits the expression of AChE, where AChE-S and GSK3β genes are transfected to two kinds of engineering cell aiming at directly exploring the effects of biatractylolide on the expression of AChE.

MEF cells are one of the mouse embryonic fibroblasts stem cell lines with properties of easy working on and physiological relevance with AD. Therefore, we used MEF as a working cell model to investigate foreign gene function and cell signaling pathway along with determining the effects of this compound. We transfected foreign AChE-S genes and GSK3β genes to MEF cells during the course of adding 50 mM LiCl and various concentrations of biatractylolide. Biatractylolide reduces the expression of AChE by inhibiting GSK3β.

4. Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that biatractylolide can inhibit the enzyme activity of AChE and downregulate the expression of AChE in a dose-dependent manner. Biatractylolide has a great potential to be used as an anti-AD drug.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Provincial Science and Technology Plan of Hunan, China (no. 2014SK3238), and Traditional Chinese Medicine of Hunan Province, China (no. 201204), to Xing Feng and Advanced Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (no. 15A117) and Xiaoxiang Endowed University Professor Fund of Hunan Normal University (no. 840140-008) to Xiao-Ping Yang.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Yong-Chao Xie and Ning Ning contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Li Z., Mu C., Wang B., Jin J. Graveoline analogs exhibiting selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity as potential lead compounds for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Molecules. 2016;21(2):p. 132. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou T., Zu G., Zhang X., et al. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in both in vivo and in vitro models of Parkinson's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101(5):480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DaRocha-Souto B., Coma M., Pérez-Nievas B. G., et al. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta mediates β-amyloid induced neuritic damage in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2012;45(1):425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W., Yang Y., Ying C., et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β protects dopaminergic neurons from MPTP toxicity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52(8):1678–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du J., Wei Y., Liu L., et al. A kinesin signaling complex mediates the ability of GSK-3β to affect mood-associated behaviors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(25):11573–11578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King T. D., Bijur G. N., Jope R. S. Caspase-3 activation induced by inhibition of mitochondrial complex I is facilitated by glycogen synthase kinase-3β and attenuated by lithium. Brain Research. 2001;919(1):106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jing P., Jin Q., Wu J., Zhang X.-J. GSK3β mediates the induced expression of synaptic acetylcholinesterase during apoptosis. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;104(2):409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anekonda T. S., Reddy P. H. Can herbs provide a new generation of drugs for treating Alzheimer's disease? Brain Research Reviews. 2005;50(2):361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pu H., Wang Z., Huang Q., et al. Biatractylolide of guinea pigs in vitro atrial muscle function. Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. 2000;16(5):60–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng X., Wang Z. L., Lin Y.-C., et al. Biatractylolide's effect on Aβ 1–40-induced dementia model rats. Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. 2009;25(7):949–951. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellman G. L., Courtney K. D., Andres V., Jr., Featherstone R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1961;7(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hostettmann K., Borloz A., Urbain A., Marston A. Natural product inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. Current Organic Chemistry. 2006;10(8):825–847. doi: 10.2174/138527206776894410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z.-D., Zhang X., Du J., et al. An aporphine alkaloid from Nelumbo nucifera as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and the primary investigation for structure-activity correlations. Natural Product Research. 2012;26(5):387–392. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.487188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung H. A., Min B.-S., Yokozawa T., Lee J.-H., Kim Y. S., Choi J. S. Anti-Alzheimer and antioxidant activities of coptidis rhizoma alkaloids. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2009;32(8):1433–1438. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan M. T. H., Orhan I., Şenol F. S., et al. Cholinesterase inhibitory activities of some flavonoid derivatives and chosen xanthone and their molecular docking studies. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2009;181(3):383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sepsova V., Karasova J. Z., Korabecny J., et al. Oximes: inhibitors of human recombinant acetylcholinesterase. A structure-activity relationship (SAR) study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(8):16882–16900. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barak D., Kronman C., Ordentlich A., et al. Acetylcholinesterase peripheral anionic site degeneracy conferred by amino acid arrays sharing a common core. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(9):6296–6305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg L., Da Andersson C. D., Artursson E., et al. Targeting acetylcholinesterase: identification of chemical leads by high throughput screening, structure determination and molecular modeling. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026039.e26039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann M. Neuronal AChE splice variants and their non-hydrolytic functions: redefining a target of AChE inhibitors? British Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;170(5):953–967. doi: 10.1111/bph.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. E., Zimmerman G., Melamed-Book N., Friedman A., Dori A., Soreq H. Transgenic inactivation of acetylcholinesterase impairs homeostasis in mouse hippocampal granule cells. Hippocampus. 2008;18(2):182–192. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore C. B., Allen I. C. Primary ear fibroblast derivation from mice. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1031(5):65–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-481-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei Y. Generation and culture of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1031(15):59–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-481-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toiber D., Berson A., Greenberg D., Melamed-Book N., Diamant S., Soreq H. N-acetylcholinesterase-induced apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003108.e3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orhan I., Şener B., Choudhary M. I., Khalid A. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of some Turkish medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;91(1):57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sternfeld M., Ming G.-L., Song H.-J., et al. Acetylcholinesterase enhances neurite growth and synapse development through alternative contributions of its hydrolytic capacity, core protein, and variable C termini. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(4):1240–1249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01240.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang X., Gao J.-S., Guan Y.-J., et al. Acetylation-dependent signal transduction for type I interferon receptor. Cell. 2007;131(1):93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]