Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the major pathogen of tuberculosis, which affects approximately one-third of the world’s population. The 6 kDa early secreted antigenic target (ESAT6) and the 10 kDa culture filtrate protein (CFP10), which are secreted by the ESX-1 system in M. tuberculosis, can contribute to mycobacterial virulence.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to research the effects of M. tuberculosis ESAT6-CFP10 protein on macrophages during a host’s was first and second exposures to M. tuberculosis.

Materials and Methods

In this study, the ESAT6 and CFP10 genes were amplified to create a fusion gene (ESAT6-CFP10) and cloned into the pET-32a(+) and pEGFP-N1 expression vectors, respectively. The recombinant pET-32a(+)-ESAT6-CFP10 plasmid was transformed into the Escherichia coli Origami strain, and the fusion protein was expressed and confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The recombinant pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10 plasmid was transfected into rat alveolar macrophage cells (NR8383). The cell line expressing the ESAT6-CFP10 protein was selected with RT-PCR and designated as NR8383-EC. Finally, the effects of the ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein on the NR8383 cell line, as well as on the newly constructed NR8383-EC cells, were further assessed.

Results

The recombinant ESAT6-CFP10 protein was expressed in E. coli and in NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages. This protein affected the proliferation and nitric oxide (NO) generation of the NR8383 and NR8383-EC cells. Although NO generation was inhibited in both cell lines, proliferation was inhibited in NR8383 while it was increased NR8383-EC.

Conclusions

The data indicate that ESAT6-CFP10 could support the survival of M. tuberculosis in the host through altering the host immune response. It also indicates that the host may gain some level of protection from a second exposure to M. tuberculosis, as evidenced by increased proliferation of NR8383-EC.

Keywords: ESAT6-CFP10 Fusion Protein, Macrophages, Cell Proliferation, Immune Protection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

1. Background

Despite attempts to understand and control Mycobacterium tuberculosis for more than a century, this pathogen remains a pressing public health threat, infecting more than one-third of the world’s population and causing almost two million deaths yearly (1). Understanding the molecular mechanism of the host/pathogen interaction is believed to be vital for controlling M. tuberculosis infections.

Previous research showed that vaccines constructed based on ESAT6 and CFP10 could reduce the M. tuberculosis burden in guinea pigs and non-human primates (2, 3). However, substantial evidence indicates that ESAT6 and CFP10 are also virulence factors. The Rv3875 gene that encodes ESAT6 is located within the region of difference 1 (RD1), which is present in all pathogenic mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, but not in attenuated M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Gue’rin (BCG) (4). ESAT6 and CFP10 are secreted as 1:1 dimers through a specific secretion system, ESX-1 (5-7). Studies of M. bovis BCG and RD1-complemented M. bovis BCG have demonstrated that the secretion of ESAT6 and CFP10 are required for the virulence, pathogenicity, and growth of M. bovis in macrophages and in mice (8, 9). In addition, ESAT6 and CFP10 are produced in the lungs of infected mice (10). The mechanisms by which ESAT6 and CFP10 contribute to virulence are not fully defined, but are believed to be involved in the cytolysis of alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages (11), favoring the intercellular spread of M. tuberculosis (12).

Nitric oxide (NO) is formed when the guanidine nitrogen of L-arginine is oxidized by a family of isoenzymes known as NO synthases. The high expression of NO in response to cytokines or to pathogen-derived molecules is important for host defense against intracellular microorganisms, such as Toxoplasma gondii, Listeria monocytogenes, Ectromelia virus, and M. tuberculosis (13-15). Recent studies showed that exposure of M. tuberculosis to NO at low concentrations killed more than 99% of the bacteria in culture (16), indicating that NO may induce macrophage apoptosis. In a TB-infection murine model, NO played an essential role in the mononuclear phagocyte killing of M. tuberculosis (17).

2. Objectives

Considering that understanding the interactions between M. tuberculosis and macrophages may be propitious for controlling tuberculosis (TB), we discussed the different effects of the recombinant ESAT6-CFP10 protein on macrophages with the host’s first and second exposures to M. tuberculosis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Expression and Purification of Recombinant ESAT6-CFP10 Protein

The recombinant fusion ESAT6-CFP10 gene was generated using overlap PCR. First, the CFP10 and ESAT6 genes were amplified from the genome of M. bovis strain C68201 (provided by Dr. Ding Jiabo, China institute of veterinary drug control) with two pairs of gene-specific primers (Table 1 (P1 and P2, P3 and P4, respectively)), which was synthesized by BGI Tech (China). The two resultant PCR products were gel-purified, then used as templates for the fusion gene ESAT6-CFP10, which was created with overlap PCR using the gene-specific primers P1 and P4. The PCR amplified ESAT6-CFP10 gene product was then cloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of the pET-32a(+) expression vector. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) host cells for histidine (His)-tagged ESAT6-CFP10 protein expression.

Table 1. Primer Sequences for ESAT6-CFP10 PCR Amplification.

| Primer | Sequence (5’- 3’) | Restriction Sites |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | ccGGATCCatggcagagatgaagac | BamH I |

| P2 | GCTGCCGCCACCGCCGCTTCCGCCACCGCCGCTTCCACCGCCACCgaagcccatttgcgaggacagcgcct | - |

| P3 | GGTGGCGGTGGAAGCGGCGGTGGCGGAAGCGGCGGTGGCGGCAGCatgacagagcagcagtggaatttcgcgg | - |

| P4 | ccAAGCTTtgcgaacatcccagtga | Hind III |

| P5 | ccAAGCTTgccaccatggcagagatgaagac | Hind III |

| P6 | ccGGATCCcgtgcgaacatcccagtga | BamH I |

The expression of the His-tagged ESAT6-CFP10 protein was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-D-l-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The expression of the His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein was detected by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining. The recombinant fusion protein was purified using a His-bind purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The contaminating endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) was removed from the purified recombinant protein using a ProteoSpinTM Endotoxin Removal Micro kit (Norgen Biotek Corporation, Canada) following the standard protocols provided by the manufacturer. The purified proteins were quantified with the Enhanced BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, China).

3.2. Western Blotting

The His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein was verified by Western blotting. In brief, the purified protein was electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE, then electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated at room temperature for 2 hours in PBST containing 5% skimmed milk to block non-specific membrane binding. This was followed by probing the membranes with bovine serum raised against M. bovis at room temperature for 2 hours. The membranes were then washed 3 times with PBST and subsequently incubated at room temperature for 2 hours with horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-bovine IgG (Sigma, USA) as the secondary antibody. The membranes were then washed again in PBST and signals were detected using super signal west pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.3. Construction of Recombinant Eukaryotic Expression Vector pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10

The ESAT6-CFP10 gene was amplified with gene-specific primers (Table 1 (P5 and P6)) synthesized by BGI Tech (China), then cloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of the pEGFP-N1 expression vector to generate the recombinant eukaryotic plasmid designated as pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10, containing a green fluorescent protein (GFP). The plasmid was confirmed by restriction analysis and gene sequencing.

3.4. Generation of the Rat Alveolar Macrophage Cell Line Expressing ESAT6-CFP10 Protein

NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages (purchased from Life and science research institute of Shanghai) were used in these experiments. The NR8383 cells were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 100 μg/mL of penicillin and streptomycin. In order to obtain NR8383 cells expressing ESAT6-CFP10, the NR8383 cells were transfected with the recombinant eukaryotic plasmid pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10. One day before transfection, 2.0 × 105/mL cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The transfections were performed with Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the transfected cells were cultured with complete RPMI-1640 medium for 18 hours. The transfected cells were selected using 10 μg/mL of G418 (Gibco, USA) until a stable NR8383 cell line expressing ESAT6-CFP10 was obtained. In addition, to further confirm and characterize the stable cell line, green fluorescence signals were detected with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan). The stable NR8383 cell line expressing ESAT6-CFP10 protein was named NR8383-EC.

3.5. Detection of ESAT6-CFP10 mRNA in NR8383-EC Cells by RT-PCR

The total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). To avoid contamination with genomic DNA, the total RNA samples were treated with RNase-Free DNase I (Takara, Japan). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Using the cDNA as a template, the ESAT6-CFP10 mRNA was amplified by PCR with gene-specific primers P1 and P4 (Table 1). The PCR products were run on a 1.0% (w/v) agarose gel and detected with ethidium bromide under UV light.

3.6. Cell Proliferation Assay

The proliferation of NR8383 or NR8383-EC in response to recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 was determined with a WST-1 assay using a WST-1 Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assay kit (Beyotime, China). In brief, the NR8383 or NR8383-EC cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and stimulated with recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 at concentrations of 10 μg/mL. At the same time, the purified product from the BL21 (DE3) (pET-32a) vector was used as a control. The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 10 μL of WST-1 for 1 hour. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm using an automatic microplate reader (Biotech, USA). The relative proliferation rate was calculated as ODtreated cells/ODuntreated cells × 100%. The experiments were conducted in triplicate, at least 3 times.

3.7. Measurement of NO Synthesis

The effect of recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 on NO generation by NR8383 and NR8383-EC cells was determined with the NO assay kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the NR8383 and NR8383-EC cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well, and pre-treated with or without LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 hours. The cells were then stimulated with or without purified recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Subsequently, Griess reagent I and Griess reagent II were added into the cell supernatants, and the optical density was measured at 540 nm using an automatic microplate reader. Sodium nitrite (NaNO2) was used to generate a standard cure. The experiments were conducted in triplicate, at least 3 times.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with a two-tailed Student’s t test. Significant differences were assigned P values of < 0.05, < 0.01, and < 0.001, which were denoted by *, **, and ***, respectively. All statistical values were calculated with SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Expression and Purification of Recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 Protein

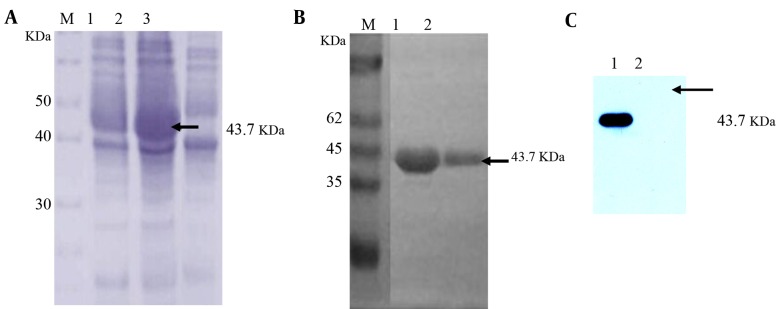

The ESAT6-CFP10 fusion gene was generated from the genome of M. bovis strain c68201 by overlap PCR amplification. It was then inserted into a pET-32a(+) expression vector, thereby generating a recombinant expression plasmid pET-32a-ESAT6-CFP10. The recombinant expression plasmid vector was confirmed by gene sequencing. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for His-ESAT6-CFP10 production. Expression of the His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein was induced with the addition of 1 mM IPTG. The expressed proteins were analyzed with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Figure 1). A Coomassie Blue-stained protein band was observed migrating with a molecular weight of about 43.7 KDa, which was consistent with the expected molecular weight (Figure 1A), indicating that the ESAT6-CFP10 gene was successfully expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Western blotting analysis with bovine positive serum raised against M. bovis further validated the expression of the recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein (Figure 1C). The His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein was purified, and SDS-PAGE showed that a high-purity recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 was obtained (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting Analysis of Recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 Fusion Protein Expression.

A, the SDS-PAGE analysis of the recombinant protein. M, middle-range protein marker; lane 1, BL21(DE3)(pET-32a-ESAT6-CFP10) in the absence of IPTG; lane 2, BL21(DE3)(pET-32a-ESAT6-CFP10) induced by IPTG; lane 3, BL21(DE3)(pET-32a) induced by IPTG. B, the purified His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein analyzed by SDS-PAGE. M, unstained protein molecular weight marker; lanes 1 - 2, purified His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein; C, the Western blotting analysis of recombinant protein using bovine positive serum raised against M. bovis; lane 1, purified recombinant fusion His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein; lane 2, His protein. Arrows indicate the positions of the target proteins.

4.2. Generation of Rat Alveolar Macrophage Cell Line NR8383-EC Expressing ESAT6-CFP10 Protein

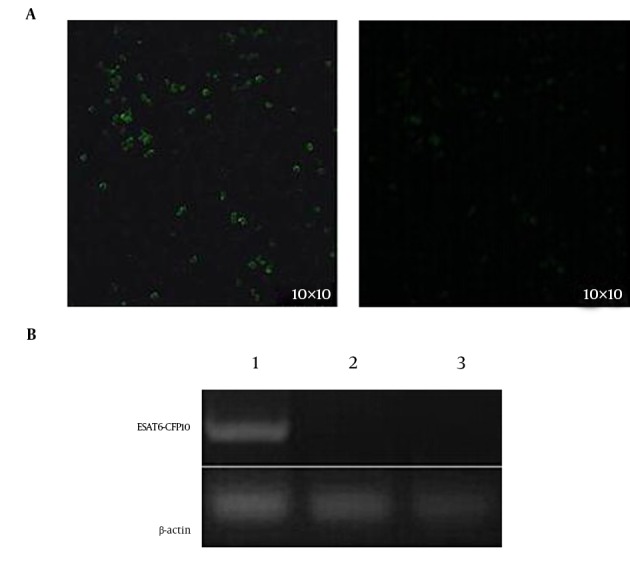

The recombinant eukaryotic expression plasmid pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10 was constructed, then confirmed by restriction analysis and gene sequencing. The ESAT6-CFP10 gene was fused to the N terminal of GFP in the recombinant plasmid. For generating the NR8383 rat alveolar macrophage cell line expressing the ESAT6-CFP10 protein, the NR8383 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10 using Lipofectamine 2000, and were screened with 10 μg/mL of G418. The green fluorescence signals were detected in NR8383-EC rat alveolar macrophages transfected with recombinant pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10 plasmid, but not in the non-transfected NR8383 macrophages (Figure 2A), which indirectly showed the expression of the ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein in the NR8383-EC cells. The expression of ESAT6-CFP10 mRNA in NR8383-EC cells was analyzed by RT-PCR. PCR products of predicted sizes for ESAT6-CFP10 (630 bp) were obtained from the NR8383-EC cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Identification of the NR8383-EC Cell Line Expressing the ESAT6-CFP10 Protein With Fluorescence and RT-PCR.

The ESAT6-CFP10 was fused to the N terminal of GFP of the pEGFP-N1 expression vector. A, the expression of the fusion protein was detected with fluorescence signals, using a fluorescence microscope; 1, NR8383 transfected with the recombinant eukaryotic plasmid pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10; 2, NR8383 non-transfected with the recombinant eukaryotic plasmid pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10; B, the mRNA level of ESAT6-CFP10 was analyzed with RT-PCR using total RNA extracted from cells; lane 1, the gene amplified from the NR8383-EC cells; lane 2, the gene amplified from NR8383 cells transfected with pEGFP-N1 plasmid; Lane 3, the gene amplified from non-transfected NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages.

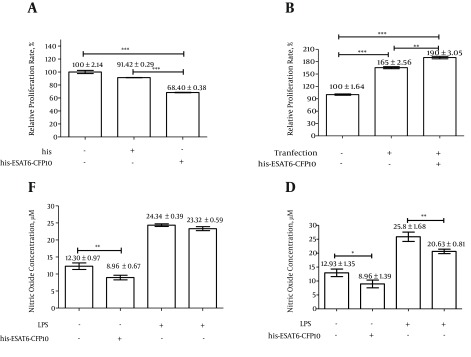

4.3. Cell Proliferation and NO Production Capacity Assays

The NR8383-EC cell line and NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages were stimulated using His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein and His protein, respectively. WST-1 analysis and Griess reactions showed that recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 affected the cell proliferation and NO generation, respectively. The ESAT6-CFP10 protein inhibited the proliferation of NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages (Figure 3A), but promoted the proliferation of NR8383-EC cells (Figure 3B). However, it also inhibited the NO generation of both NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages (Figure 3C) and NR8383-EC cells (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Cell Proliferation and NO Production Capacity Assays.

A, the proliferation of NR8383 or B, NR8383-EC in response to recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 was determined by WST-1 assay. The cells were stimulated with recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 at concentrations of 10 μg/mL, then proliferation was determined. At the same time, the purified product from BL21(DE3) (pET-32a) was used as a control. The NO generation effect of recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 on C, NR8383 or D, NR8383-EC was determined by the NO assay kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were pre-treated with or without LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 hours, and were then stimulated with or without purified recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours. NO generation was then determined. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The experiment was repeated three times.

5. Discussion

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the primary causative agent of human tuberculosis, which remains a major global health problem. M. tuberculosis is a typical intracellular pathogen that resides within the host macrophages and dendritic cells. Invasion of macrophages by M. tuberculosis is a critical step in the establishment of tuberculosis (TB) infections. Macrophage apoptosis is a host defense mechanism against M. tuberculosis infection (18, 19). On the other hand, M. tuberculosis could survive in the host macrophages by inhibiting their apoptosis. Some researchers have indicated that avirulent mycobacterial species, such as the attenuated M. bovis BCG, cause considerably higher rates of macrophage apoptosis than do the virulent M. tuberculosis species (20). Comparative analyses of the genomic sequences of M. tuberculosis (21) and M. bovis (22) with that of the attenuated M. bovis BCG strain have identified a number of proteins deleted in BCG. These include the small secreted ESAT6 and CFP10, which are known to contribute to microbial virulence. Therefore, the effects of ESAT6 and CFP10 on macrophage apoptosis are very important for studying and understanding the mechanisms of tuberculosis.

In this study, the His-ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein was expressed in an E. coli system, which was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the successful production of the fusion protein in soluble form. This form was thought to be the best condition for the test, because of its complete natural structure. The Western blot analysis confirmed that the immunogenicity of the fusion protein was in good condition. These results also indicated that the fusion expression of ESAT6 and CFP10 has no negative effect on the biological activity of these key proteins involved in tuberculosis virulence.

Obtaining a cell line that expresses the ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein is very important for the study of the interactions between these proteins and macrophages during M. tuberculosis infections. In this study, using a eukaryotic expression plasmid pEGFP-N1-ESAT6-CFP10, a NR8383-EC rat alveolar macrophage cell line that expresses ESAT6-CFP10 protein was constructed. It was verified by RT-PCR and fluorescence assay. The ESAT6-CFP10 gene was amplified from the NR8383-EC cDNA by RT-PCR, and fluorescence was detected in the NR8383-EC cells. Hence, these combined results showed that the NR8383-EC cell line expressing the ESAT6-CFP10 protein was constructed successfully.

To understand the effects of M. tuberculosis on macrophages when the host is challenged with M. tuberculosis the first and second times, the His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein was used to stimulate the response of the NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages and the NR8383-EC macrophage cell line that expressed ESAT6-CFP10 protein. The effects of recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein on NR8383 and NR8383-EC were then determined by measuring the cell proliferation and NO generation.

The results of NO generation showed that the recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein inhibited the NO generation of both the NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages and the NR8383-EC cell line. However, the cell proliferation results showed that the recombinant protein His-ESAT6-CFP10 inhibited the proliferation of NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages, but promoted the proliferation of the NR8383-EC cell line. Therefore, these results indicated that M. tuberculosis could escape the host immune defense by continuous inhibition of NO generation, but it could promote or inhibit the apoptosis of macrophages in order to regulate the number of cells by some responses or interactions (23) when the host is first infected by M. tuberculosis or when it again comes into contact M. tuberculosis. This was evidenced by differences in proliferation between the NR8383-EC cell line, which carried the ESAT6-CFP10 fusion protein, and NR8383, which did not. These findings lead us to believe that significantly different responses protect the host from M. tuberculosis infections between the first and second M. tuberculosis exposures.

In conclusion, the NR8383-EC cell line and recombinant His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein were successfully constructed. The His-ESAT6-CFP10 protein stimulation of the NR8383-EC cell line and of the NR8383 rat alveolar macrophages showed different effects. These results provide novel valuable information and new ideas for studying the mechanisms of infection and the diagnostic methods for tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ding Jiabo from the China institute of veterinary drug control, Beijing, China, for provision of heat-killed Mycobacterium bovine isolates.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:The core idea of this work came from Hongjun Yang. Xiaoli Xie and Liang Zhang were advisors on the project and contributed to the analysis of the data. Meng Han collected the data, cultured the cells, and performed the molecular tests, and also wrote the manuscript in collaboration with Xiaoli Xie. Laixing Liu and Zuye Gu assisted in the molecular tests. Mei Yang assisted in culturing the cells.

Funding/Support:This work was financed by the natural science foundation of Shandong province (NO.ZR2015YL069) and the natural high technology research and development program of China (NO.2012AA101302-6).

References

- 1.Raviglione MC, Snider DJ, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA. 1995;273(3):220–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen AW, Williams A, Okkels LM, Hatch G, Andersen P. Protective effect of a tuberculosis subunit vaccine based on a fusion of antigen 85B and ESAT-6 in the aerosol guinea pig model. Infect Immun. 2004;72(10):6148–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6148-6150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langermans JA, Doherty TM, Vervenne RA, van der Laan T, Lyashchenko K, Greenwald R, et al. Protection of macaques against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by a subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85B and ESAT-6. Vaccine. 2005;23(21):2740–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker HG, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1996;64(1):16–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.16-22.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champion PA, Cox JS. Protein secretion systems in Mycobacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(6):1376–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behr MA, Sherman DR. Mycobacterial virulence and specialized secretion: same story, different ending. Nat Med. 2007;13(3):286–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0307-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdallah AM, Gey van Pittius NC, Champion PA, Cox J, Luirink J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, et al. Type VII secretion--mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(11):883–91. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, et al. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(21):12420–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pym AS, Brodin P, Brosch R, Huerre M, Cole ST. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46(3):709–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majlessi L, Brodin P, Brosch R, Rojas MJ, Khun H, Huerre M, et al. Influence of ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (RD1) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on the interaction between mycobacteria and the host immune system. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3570–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao LY, Guo S, McLaughlin B, Morisaki H, Engel JN, Brown EJ. A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(6):1677–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, et al. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell. 2007;129(7):1287–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo RS, Bloom BR. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175(4):1111–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(16):8841–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang FC. Perspectives series: host/pathogen interactions. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-related antimicrobial activity. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(12):2818–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI119473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long R, Light B, Talbot JA. Mycobacteriocidal action of exogenous nitric oxide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(2):403–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMicking JD, North RJ, LaCourse R, Mudgett JS, Shah SK, Nathan CF. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(10):5243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fratazzi C, Arbeit RD, Carini C, Remold HG. Programmed cell death of Mycobacterium avium serovar 4-infected human macrophages prevents the mycobacteria from spreading and induces mycobacterial growth inhibition by freshly added, uninfected macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;158(9):4320–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keane J, Shurtleff B, Kornfeld H. TNF-dependent BALB/c murine macrophage apoptosis following Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection inhibits bacillary growth in an IFN-γ independent manner. Tuberculosis. 2002;82(2-3):55–61. doi: 10.1054/tube.2002.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keane J, Remold HG, Kornfeld H. Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains evade apoptosis of infected alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164(4):2016–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393(6685):537–44. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joung SM, Jeon SJ, Lim YJ, Lim JS, Choi BS, Choi IY, et al. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Korea, the Korean vaccine strain for substantial production. Genome Announc. 2013;1(2):e00069–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi HH, Shin DM, Kang G, Kim KH, Park JB, Hur GM, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response is involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein ESAT-6-mediated apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(11):2445–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]