Abstract

Breathing is generated by a respiratory network in the brainstem. At its core, a population of neurons expressing neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1R) and the peptide somatostatin (SST) form the preBötzinger Complex (preBötC), a site essential for the generation of breathing. PreBötC interneurons generate rhythm and follower neurons shape motor outputs by activating upper airway respiratory muscles. Since NK1R-expressing preBötC neurons are preferentially inhibited by μ-opioid receptors via activation of GIRK channels, NK1R stimulation may also involve GIRK channels. Hence, we identify the contribution of GIRK channels to rhythm, motor output and respiratory modulation by NK1Rs and SST. In adult rats, GIRK channels were identified in NK1R-expressing preBötC cells. Their activation decreased breathing rate and genioglossus muscle activity, an important upper airway muscle. NK1R activation increased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity in wild-type mice, but not in mice lacking GIRK2 subunits (GIRK2−/−). Conversely, SST decreased rhythmic breathing via SST2 receptors, reduced genioglossus muscle activity likely through SST4 receptors, but did not involve GIRK channels. In summary, NK1R stimulation of rhythm and motor output involved GIRK channels, whereas SST inhibited rhythm and motor output via two SST receptor subtypes, therefore revealing separate circuits mediating rhythm and motor output.

Breathing is an autonomic behaviour generated by a complex respiratory network in the brainstem. At its core is the preBötzinger Complex (preBötC), a population of neurons generating breathing1 by rhythmically activating respiratory neurons. In the preBötC, a population of interneurons generate rhythmic activity and other populations of follower neurons shape motor outputs and drive the neural circuits that activate the diaphragm during inspiration. PreBötC neurons also project to premotor hypoglossal neurons that drive hypoglossal motoneurons and upper airway muscle activity during inspiration2,3,4,5. PreBötC neurons regulate the amplitude of hypoglossal motor output because progressive, but not selective, destruction of inspiratory preBötC neurons decreases hypoglossal motor output in addition to affecting rhythmic breathing6. The functional roles and the identity of the preBötC neurons regulating rhythmic breathing and upper airway muscle activity have not been described.

PreBötC neurons express various G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) that are critical to maintaining breathing. A subpopulation of preBötC neurons expressing excitatory neurokinin-1 receptors (NK-1R) are necessary to generate breathing and their destruction impairs rhythmic breathing7. Another subpopulation of preBötC neurons contain somatostatin (SST)8, an inhibitory peptide that reduces neuronal activity by activating cognate SST receptors9. SST inhibits rhythmic breathing10 and inhibition of SST-expressing preBötC cells abolishes respiratory activity11, but the types of SST receptors involved are unclear12. Importantly, rhythmogenic preBötC interneurons are derived from a set of precursors that express the homeobox gene Dbx14. Interestingly, Dbx1-expressing preBötC neurons also co-expressed SST2A receptors9 and regulate hypoglossal motor output3. In addition, almost all NK-1R-expressing preBötC cells co-express SST8. SST-expressing preBötC neurons project to hypoglossal premotor areas5 and may therefore regulate upper airway muscle activity. In addition to SST and NK-1Rs, μ-opioid receptors (MOR) are present in preBötC neurons13 and their activation inhibits rhythmic breathing and upper muscle activity in vivo14 and in vitro15. Although the roles of MOR have been characterized14,16, the functional roles of NK-1R, SST, and SST receptors in regulating rhythmic breathing and upper airway muscle activity, especially in vivo, are unclear.

NK-1R and MOR are GPCRs that modulate neuronal activity through various pathways including calcium channels, adenylate cyclase, and/or G-protein-gated inwardly-rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels. In the preBötC, MORs inhibit rhythmic breathing through potassium channels16, and we recently identified that GIRK channels contribute to MOR respiratory slowing17. In nucleus basalis neurons, GIRK channels contribute to neuronal excitation by the endogenous NK-1R agonist substance P18. In the preBötC region, MORs reduce rhythmic breathing by preferentially inhibiting NK-1R-expressing preBötC neurons14 which suggests that NK-1Rs and MORs may involve similar pathways. Here, we propose that GIRK channels contribute to excitation of rhythmic breathing by NK-1Rs. Although MORs, SST, and SST2A receptors are co-expressed in NK-1R-expressing preBötC cells9, activation of SST receptors inhibits glutamate release by activating potassium leak current or by inhibiting voltage-dependent calcium current19. We therefore suggest that the mechanisms underlying excitation by NK-1R and inhibition by MOR may differ from those regulating SST inhibition.

To better understand the circuitry generating rhythmic breathing and motor outputs, we aimed to establish the functional roles of GIRK-expressing preBötC neurons in mediating rhythmic breathing and hypoglossal motor activity, as well as excitation by NK-1Rs and inhibition by SST in adult rodents in vivo. Here, we propose a functional framework identifying the roles of GIRK channels, NK-1Rs, and SST receptors in rhythmic breathing and motor output.

Methods

Experimental animals

All procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and were approved by the University of Toronto Animal Care Committee. 33 adult male Wistar rats (250–350 g, Charles River, Saint-Constant, Quebec, Canada), 8 wild-type mice (4 females and 4 males), and 9 mice lacking the GIRK2 subunit (GIRK2−/−, 5 females and 4 males) were used for physiological recordings (body weight: 40–50 g). The GIRK channel subunits GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 form 4 types of tetramers and the absence of GIRK2 subunits eliminates 3 out of 4 tetramers in the brain20,21. The generation of GIRK2−/− mice was described previously20. Mice and rats were housed with free access to food and water under a 12-hour light 12-hour dark cycle (lights on at 7 am).

Microperfusion and recordings in anesthetized adult rodents

In anesthetized adult male rats, we used reverse-microdialysis to unilaterally microperfuse selected agents into the preBötC. The experimental procedures were as described previously14,22. Briefly, we recorded activities of diaphragm and genioglossus muscles in isoflurane-anesthetized (2–2.5%), tracheotomised and spontaneously breathing (50% oxygen gas mixture, balance nitrogen) adult rats. Diaphragm muscle activity was recorded using stainless steel bipolar electrodes positioned and sutured on the right side of the crural diaphragm. Genioglossus muscle activity was recorded using two stainless steel needles inserted into the muscle. Electromyography signals were amplified (CWE Inc., Ardmore, Pennsylvania, USA), band-pass filtered (100–1000 Hz), integrated and digitized at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz using CED acquisition system and Spike v6 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited, Cambridge, England). Rats were kept warm with a heating pad during the experiments. Using a dorsal approach, a microdialysis probe (CX-I-12-01, Eicom, Kyoto, Japan) of 200 μm diameter and 1 mm diffusing membrane length was inserted into the preBötC using a stereotaxic frame and micromanipulator (ASI Instruments, Warren, Michigan, USA). The probe was placed 12.2 mm posterior, 2 mm lateral, and 10.5 mm ventral to bregma according to standard rat brain atlas23. We used three criteria to accurately target the preBötC, to position the probe and to confirm its location as described previously14,22. (i) When the probe was inserted in the brain, genioglossus muscle activity showed a reduction of about 30% as it reached the vicinity of the preBötC. (ii) Microperfusion of the μ-opioid receptor agonist DAMGO 5 μM decreased respiratory rate by approximately 50%14. (iii) Post-mortem histology was used to confirm the probe location in the preBötC using anatomical markers such as the semi-compact division of nucleus ambiguus, the caudal part of the facial nucleus, and immunohistochemistry of NK-1R. In rats, we used the caudal part of the facial nucleus as a reference to identify the brain section located 11.6 mm posterior to Bregma. In mice, we used the caudal part of the facial nucleus to identify the brain section 6.5 mm posterior to Bregma. Once the coronal section where the probe was located was identified, we used the nucleus ambiguus to determine the medial-lateral and dorsal ventral coordinates. We used these three anatomical and functional criteria and experience from our previous studies to confirm that the probes were positioned in the region of the preBötC. On rare occasions (1/20 experiments), the probes damaged the preBötC and respiratory rhythm was irregular and unstable. In such an event, we did not continue the experiment. Fresh artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) was made according to the following composition (in mM): NaCl (125), KCl (3), KH2PO4 (1), CaCl2 (2), MgSO4 (1), NaHCO3 (25), and glucose (30). pH was adjusted to 7.4 by bubbling CO2 into aCSF. A microdialysis probe was perfused with aCSF and baseline levels of the physiological variables were recorded for least 30 min followed by 120 min of recordings during perfusion of the selected agents. Breathing rate, diaphragm muscle amplitude and genioglossus muscle amplitude were averaged over a 10 min period at the end of 30 min of baseline, and over a 10 min period after 30 min of drug perfusion. We applied different GPCR agonists and antagonists and channel modulators. To activate GIRK channels, we added flupirtine (200 μM) or ML-297 (50 or 200 μM) to the aCSF perfusing the preBötC as previously described (Montandon et al.17). We also perfused the NK1-R agonist GR73632 (50 μM), the SST2 receptor antagonist CYN-154806 (20 μM)24, the peptide somatostatin (200 μM)25, the SST4 receptor agonist (NNC 26–9100) and the GIRK channel blocker Tertiapin Q (1 μM). All drugs were obtained from Tocris (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

In anesthetized (isoflurane, 1.5–2%), spontaneously breathing (50% oxygen, balance nitrogen) adult mice, we also used reverse microdialysis to perfuse agents into the preBötC of wild-type and GIRK2−/− animals. We recorded diaphragm and genioglossus muscle activities using a similar approach to the rats and as previously described17. The mice were also kept warm with a heating pad. We inserted the microdialysis probe into the brainstem 6.7 mm posterior, 1.2 mm lateral, and 5.7 mm ventral to bregma according to standard mouse brain atlas26. For wild-type or GIRK2−/− mice, baseline levels were recorded for at least 30 min followed by 120 min of recordings. The anatomical and functional criteria defined in rats were also used for experiments in mice. Because of the random production of GIRK2−/− knockout animals during breeding, we did not randomize wild-type and GIRK2−/− mice. However, we alternated recordings from wild-type and knockout mice to avoid order effects or experimental conditions that may affect one group temporarily. To avoid experimenter bias, similar standard procedures, timelines for dosing, and automated analyses were used for both animal groups. Breathing rate, diaphragm muscle amplitude and genioglossus muscle amplitude were averaged over a 10 min period at the end of 30 min of baseline and over a 10 min period after 30 min of drug perfusion.

Construction of correlation maps

We constructed correlation maps to relate the location of the intervention sites with the resultant effect on respiratory activity as previously described and validated14,22. The rationale for the construction of correlation maps is that for a locus of effect of drugs (ML-297) at any particular brainstem site, the latency for the drug to diffuse through the tissue and to progressively change respiratory activity will vary as a function of the distance of the probe from the effective site. We first determined the locations of the intervention (perfusion) sites by using anatomical markers and standard brain maps23. To determine the anterior-posterior coordinates, we used the caudal end of the facial nucleus as the reference point which is located 11.6 mm posterior to bregma. The dorsal-ventral and medial-lateral coordinates were defined using the nucleus ambiguus and standard brain maps. For each animal, we then calculated the latencies to a 10% change in respiratory rate or the percentage of reduction after 30 min of drug perfusion. For every possible sets of coordinates, we then calculated the distances from the perfusion sites to the corresponding set of coordinates and correlated these distances with the latencies for the effects on respiratory activities or percentage of rate change. We first presented the correlation between distances from preBötC (coordinates −12.3 mm anterior, 2 mm medial, and 10 mm ventral to bregma) to perfusion sites and latencies or rate changes. Then, using Matlab 12 software (Mathworks, Natick, MA), the correlation coefficients (0 < R < 1) were calculated for every set of coordinates and plotted as colour pixels (blue to red) in a standard brain map 12.3 mm posterior to bregma23.

Immunohistochemistry in rats

Animals were euthanized with isoflurane, perfused with phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4), and then paraformaldehyde (PFA, 4%). Brain were harvested and fixed for 4 hours in PFA, and then transferred to sodium citrate (1%) overnight for antigen retrieval. Brains were then boiled for 4 min in sodium citrate and immersed in sucrose solution (30%) overnight. Brains were frozen at −20 °C and coronal sections (50 μm) were cut in a cryostat. Sections were then incubated with rabbit anti-GIRK2 (1:500, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) and goat anti-NK-1 (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) antibodies, and with donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 488 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and anti-goat IgG Alexa 594 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary antibodies. Sections were then incubated with DAPI (NucBlue, Life Technologies Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada) mounted on slides, and then visualized with an epifluorescence microscope (AxioScan, Leica Microsystems Inc., Concord, ON, Canada). We focused our immunofluorescence on the 300 μm-extension of the medulla around preBötC neurons (six consecutive 50 μm sections starting 150 μm caudal to the preBötC). As anatomical markers, we use the caudal part of the hypoglossal motor nucleus, the inferior olive, the nucleus ambiguus, and the facial nucleus. We counted numbers of immunopositive cells within a circle of 1 mm of diameter centered in the preBötC. To identify the location of the preBötC, we performed additional immunohistochemistry for NK-1Rs7 using the Avidin-Biotin Complex method and chromogen diaminobenzidine staining. The antibodies used were rabbit anti-NK1R (1:1000, AB-N04, Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA, USA) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Statistical Analysis

In Figures, group data are presented as mean ± standard error mean (S.E.M.) and individual data are also displayed. We used S.E.M. to improve visibility in graphs. In Results section, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For the studies in rats, we used 1-way ANOVAs with the repeated factor being treatments with aCSF or drugs. For the studies in mice, we tested for group differences using 2-way repeated measure ANOVA tests, with a factor being genotype (i.e. wild-type or GIRK2−/−) and the repeated factor being drug treatments (i.e. aCSF or drugs of choice). If the ANOVA was statistically significant, an All Pairwise Multiple Comparison Procedure (Holm-Sidak tests) was then used to determine significant differences between conditions (aCSF/baseline versus drug). When statistical tests were not significant, the power of the test was indicated to avoid interpreting non-significant tests as evidence of absence of effects. All hypothesis tests are two-tailed with the level of significance set at P < 0.05. All tests were performed with SigmaPlot version 11 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

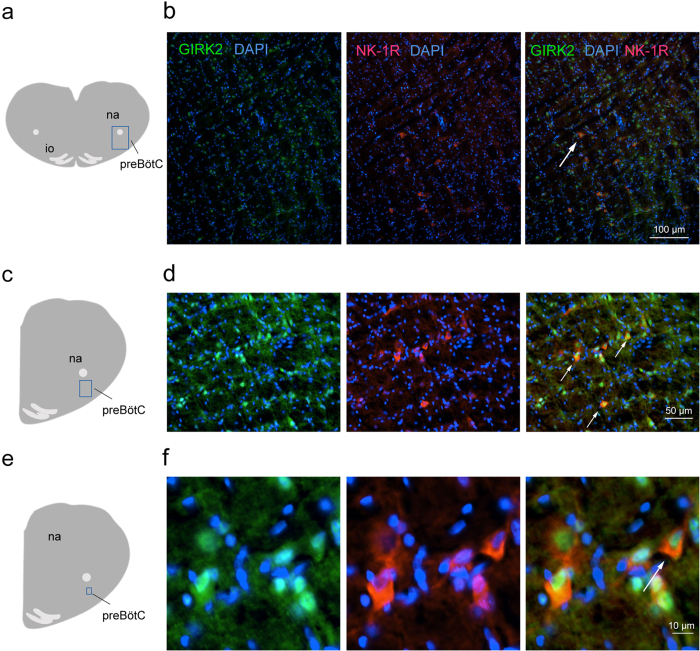

GIRK2 subunit expression in the preBötC

In neurons, the GIRK2 subunit is an integral subunit found in 3 out of 4 GIRK tetramers21. The GIRK2 subunit is expressed in the region of the preBötC and modulates rhythmic breathing in rodents17. To identify the types of preBötC cells expressing GIRK channels, we visualized the expression of GIRK2 subunits and NK-1Rs using immunohistochemistry of brainstem sections from adult rats (n = 3). GIRK2 subunits were present in the somas of small cells (diameter < 100 μm) in the preBötC (Fig. 1a), ventral to the nucleus ambiguus (anterior-posterior position: 12.3 mm posterior to bregma) and caudal to the Bötzinger Complex (Fig. 1b). Combined with the nuclear marker DAPI, we determined that GIRK2 subunits were expressed in 22.6 ± 4.2% of cells in the preBötC (n = 3, Fig. 1c,d). Cells with somas expressing NK-1R all co-expressed GIRK2 subunits (Fig. 1e,f). We counted that 15.1 ± 4.6% of GIRK2-positive cells co-expressed NK-1Rs (n = 3). These results showed that a relatively small proportion of cells in the preBötC region expressed GIRK2 subunits and NK-1Rs.

Figure 1. Expression of GIRK2 subunits and neurokinin-1 receptors in preBötC neurons of adult rats.

In the region of the preBötC ventral to the nucleus ambiguus (a), GIRK2 subunits were expressed in somas (GIRK2 green, DAPI, blue, b). Neurokinin-1 receptors were expressed in the preBötC region (red, c). All cells expressing NK-1Rs also expressed GIRK2 subunits (white arrow, d). Magnification showed perinuclear expression of GIRK2 subunits in cells of the preBötC region (e,f). NK-1Rs were found in somas and co-expressed with GIRK2 subunits. Results are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars 100, 50, and 10 μm for upper, middle and lower panels respectively. na, nucleus ambiguus. io, inferior olive.

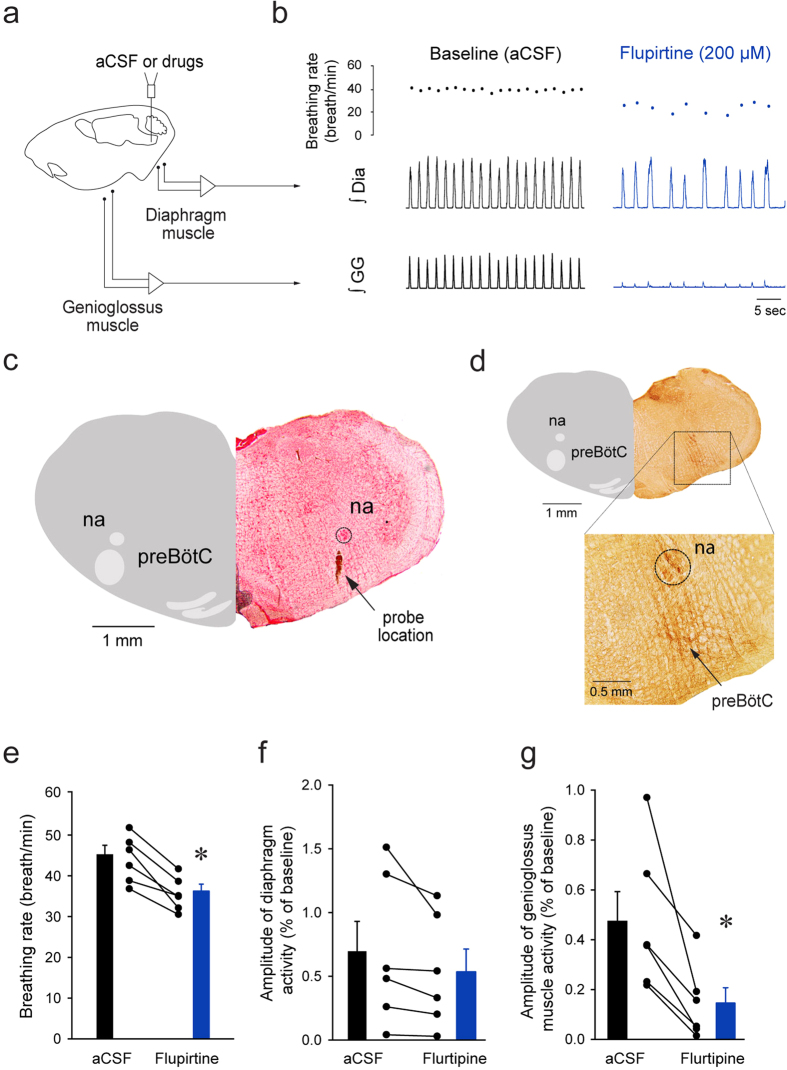

Functional role of GIRK channels in the preBötC

Activation of GIRK channels using flupirtine inhibits rhythmic breathing in rats and wild-type mice, but not in GIRK2 subunit knockout mice (GIRK2−/−)17, suggesting that flupirtine preferentially activates GIRK channels. To further establish the functional role of GIRK channels in modulating upper airway muscle activity, we replicated previous experiments17 by micro-perfusing flupirtine into the preBötC of anesthetized adult rats using reverse microdialysis while recording diaphragm and genioglossus muscle activity (Fig. 2a) as previously described17. In a representative rat, flupirtine (200 μM) decreased breathing rate when perfused into the region of the preBötC as previously demonstrated17. Interestingly, flupirtine also decreased genioglossus muscle activity (Fig. 2b) when perfused in the preBötC region (Fig. 2c) as identified by the high expression NK-1Rs, ventral to the nucleus ambiguus (Fig. 2d)7,14. Flupirtine (200 μM) significantly decreased breathing rate by 19.1 ± 7.4% (P = 0.002, n = 6, Fig. 2e), similar to our previous study17. Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not significantly affected by flupirtine (P = 0.105, n = 6, Fig. 2f). Importantly, flupirtine also significantly decreased genioglossus muscle amplitude by 72.5 ± 22.6% (P = 0.017, n = 6, Fig. 2g).

Figure 2. Activation of GIRK channels with flupirtine at the preBötC decreased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity in anesthetized rats.

Microperfusion (a) of flupirtine (200 μM) in the preBötC region reduced breathing rate and genioglossus muscle amplitude, but not diaphragm amplitude (b). Dots indicate breathing rate for each breath. The microperfusion probe was positioned in the region of the preBötC (c) identified by high expression of NK-1Rs (d). Ventral to the nucleus ambiguus, NK-1Rs were highly expressed and identified the preBötC region (see magnification). Flupirtine significantly reduced breathing rate (n = 6, e), but not diaphragm muscle amplitude (f). Flupirtine also significantly diminished genioglossus muscle amplitude (g). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Dia, diaphragm muscle. GG, genioglossus muscle.

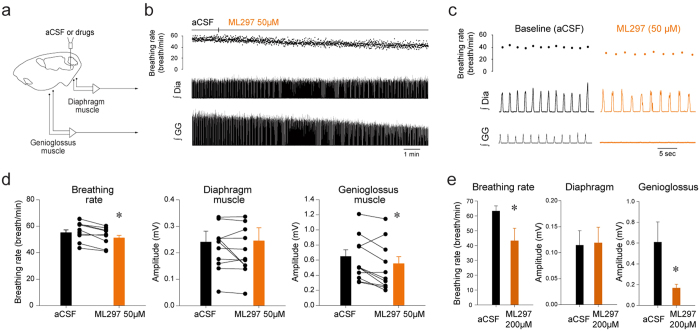

Selective activation of GIRK channels in the preBötC

In addition to modulate GIRK channels, flupirtine activates voltage-sensitive potassium channels, indirectly antagonizes NMDA receptors and modulates GABAA receptors27,28. To selectively target GIRK channels, we micro-perfused the GIRK channel activator ML29729. Microperfusion of ML297 (50 μM) into the preBötC region (Fig. 3a) decreased breathing rate and genioglossus muscle amplitude, but not diaphragm amplitude (Fig. 3b,c). ML297 (50 μM) significantly decreased breathing rate (Fig. 3d, P = 0.005, n = 11) and genioglossus muscle amplitude (P = 0.016, n = 11), but did not change diaphragm muscle amplitude (P = 0.898, n = 11). In a separate set of experiments, ML297 perfused at higher concentration (200 μM) substantially decreased breathing rate (Fig. 3e, P = 0.049, n = 4) and genioglossus muscle (P = 0.045, n = 4). Overall, these results identified that activation of GIRK channels at the preBötC level decreased breathing rate and genioglossus muscle activity.

Figure 3. Activation of GIRK channels with ML297 applied in the preBötC region decreased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude in anesthetized rats.

Microperfusion (a) the selective GIRK channel activator ML297 (50 μM) in the preBötC region reduced breathing rate and genioglossus muscle amplitude, but not diaphragm amplitude (b,c). Dots indicate breathing rate for each breath. ML297 (50 μM) significantly reduced breathing rate (n = 11, d), but not diaphragm muscle amplitude (f). ML297 also significantly diminished genioglossus muscle amplitude. ML297 at higher concentration (200 μM strongly reduced breathing rate and genioglossus muscle amplitude, but not diaphragm amplitude (e). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Dia, diaphragm muscle. GG, genioglossus muscle.

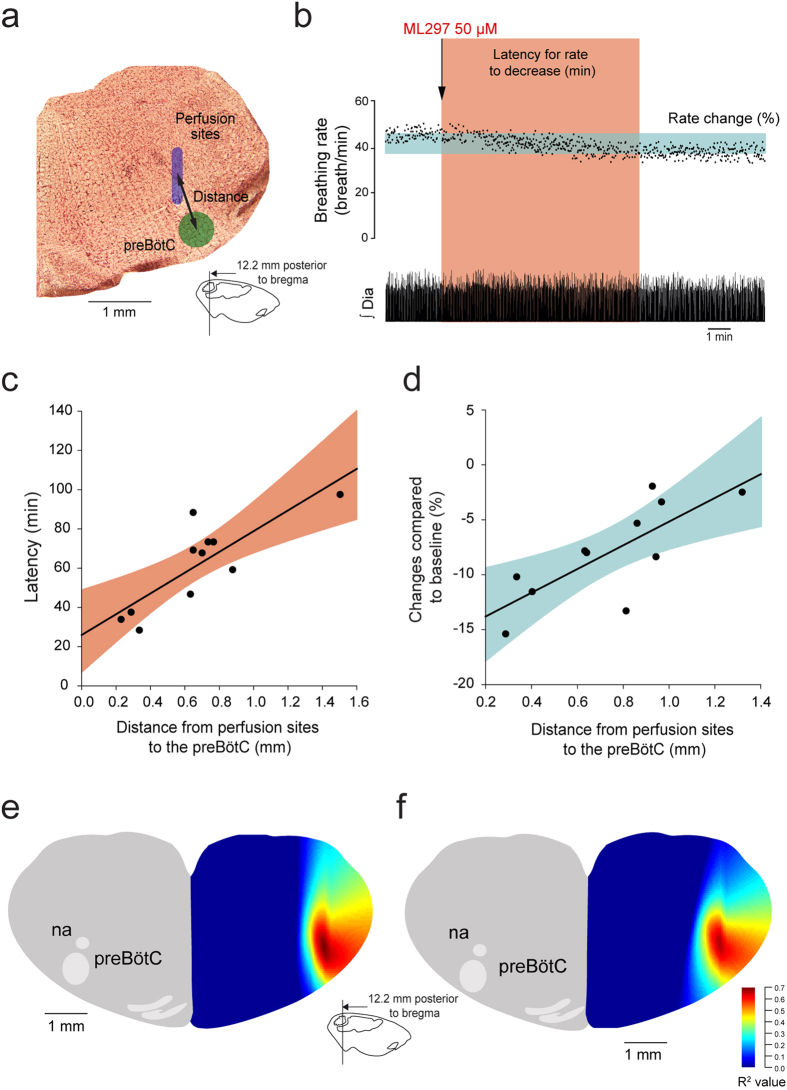

Focal activation of GIRK channels in the preBötC

To better identify the region of the ventrolateral medulla where ML297 activates GIRK channels, we quantified the relationship between the proximity of the perfusion site to the preBötC and the latency for ML297 to change breathing. If ML297 activates GIRK channels specifically at the preBötC, then the latency for the drug to perfuse through tissue and affect breathing should be shorter when the perfusion is performed close to the preBötC than when it is performed away from it. Based on this concept, we related the distance from the perfusion site to the center of the preBötC (Fig. 4a) with the latency for ML-297 to decrease breathing rate by 10% (Fig. 4b) as previously validated14,22. For each experiment, we calculated the latency for ML297 to decrease breathing rate by 10% and the distance from perfusion site to the center of the preBötC. The center of the preBötC used in this study was 12.3 mm posterior, 2 mm lateral, and 10 mm ventral to Bregma23. We then found a significant correlation between distances and latencies (R = 0.818, P = 0.002, n = 11, Fig. 4c). Similarly we related the distances with the degree of reduction induced by ML297 and found a positive significant correlation between distances and rate changes (R = 0.766, P = 0.006, n = 11, Fig. 4d). These correlations suggest that close perfusion of ML297 to the preBötC quickly and substantially decreased breathing rate compared to perfusions away from it. As examples in experiments where perfusion occurred close to the preBötC (distance < 0.4 mm), ML297 reduced breathing rate by more than 15% (Fig. 4d). To eliminate the possibility that there were other sites in the medulla that were equally sensitive to ML297 than the preBötC, we calculated the correlation coefficients for all the possible sites in the medulla and created color maps representing the area of the medulla where ML297 induced a fast and substantial decrease in breathing rate. In the region of the preBötC, correlation coefficients were above 0.6 (red spot) suggesting high correlation between latencies and distances (Fig. 4e). A similar correlation map was generated for distances and rate changes and identified a similar region with high correlation (Fig. 4f). These data therefore identified the preBötC as an area of the medulla highly sensitive to ML297 and suggest that selective activation of GIRK channels in the preBötC decreased breathing rate.

Figure 4. Relationships between proximity of perfusion sites to preBötC and changes in breathing rate induced by ML297 in anesthetized rats.

For each experiment where ML297 was perfused in the preBötC region, the distance from the perfusion site to the center of the preBötC was calculated (a). Also, the latency for ML297 (50 μM) to decrease breathing rate by 10% (red shade, b) or the change in rate after 30 min of perfusion (blue shade) was estimated. The correlation between latencies and distances for n = 11 animals was then calculated. Significant and positive correlations between distances and latencies (R = 0.818, P = 0.002, n = 11, c), and distances and rate changes (R = 0.766, P = 0.006, n = 11, d) were found suggesting that ML297 induced faster and more pronounced reductions in rate when perfused close to the preBötC. Correlation maps indicated regions of the brainstem where correlation between distances and latencies (e) or changes (f) were higher (red hot spots), and these hotspots correspond to the preBötC.

NK-1R modulates rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity through GIRK channels

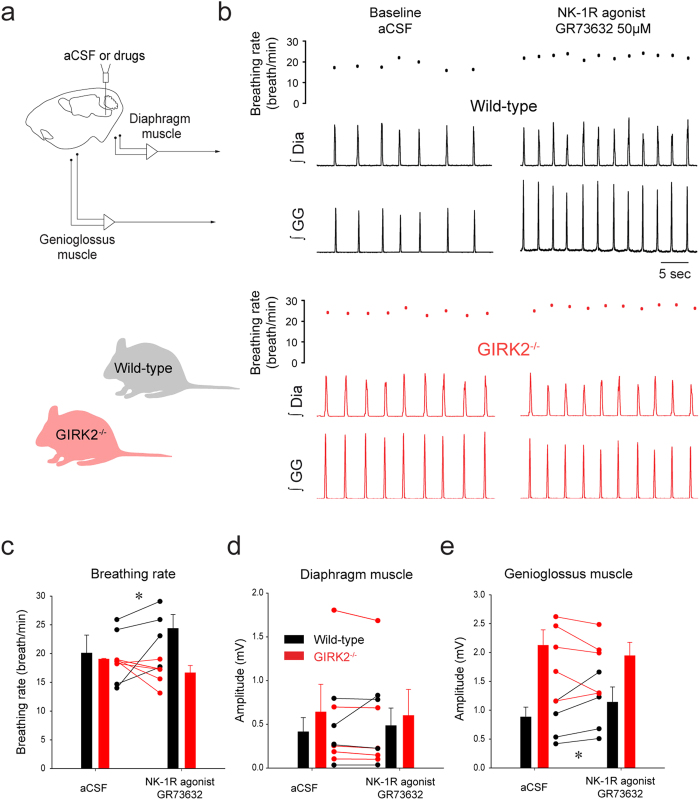

Destruction of NK-1R-expressing neurons severely disrupts rhythmic breathing7, but the functional roles of NK-1R in mediating rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity in vivo remains unclear25,30. We therefore microperfused the NK-1R agonist GR73632 into the preBötC of anesthetized wild-type mice (Fig. 5a). GR73632 (50 μM) applied to the preBötC increased rhythmic breathing in the wild-type mice by 25.7 ± 15.6% (P = 0.048, n = 4, Fig. 5b,c). Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not significantly changed by GR73632 (P = 0.885, n = 4, Fig. 5b,d). GR73632 significantly increased genioglossus muscle amplitude by 26.4 ± 9.8% in wild-type mice (P = 0.035, Fig. 5b,e).

Figure 5. Activation of NK-1Rs increased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude in the wild-type but not in the GIRK2−/− mice.

Microperfusion of the NK-1R agonist GR73632 (50 μM) into the preBötC (a) significantly increased breathing rate in wild-type mice (b), but not in GIRK2−/− mice. Dots indicate breathing rate for each breath. Mean data showed that breathing rate was increased in wild-type mice (n = 4), but not GIRK2−/− mice (n = 5, c). Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not changed by GR73632 either in wild-type nor in GIRK2−/− mice (d). Genioglossus muscle amplitude was increased by GR73632 in wild-type, but not in GIRK2−/− mice (e). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal.

NK-1R-expressing preBötC neurons are selectively inhibited by MOR in vitro14 and respiratory inhibition by MOR depends on GIRK channels17. Since NK-1R excitation inhibits GIRK channels in the nucleus basalis18, excitation of preBötC neurons by NK-1R may also involve GIRK channels. In mice lacking GIRK2 subunits, we applied GR73632 (50 μM) to the preBötC and breathing rate was unchanged unlike the stimulation elicited in the wild-type mice (2-way ANOVA, mouse genotype x drugs, P = 0.018, Fig. 5b,c). The two-way ANOVA (drugs x genotype) was not significant for diaphragm amplitude (P = 0.228, Fig. 5d). Similar to breathing rate, genioglossus muscle amplitude was increased by GR73632 in the wild-type mice but not in the GIRK2 mice (2-way ANOVA, mouse genotype x drugs, P = 0.016, Fig. 5b,e). These data identify that GIRK channels significantly contribute to the excitatory effect of NK-1R on respiratory activity.

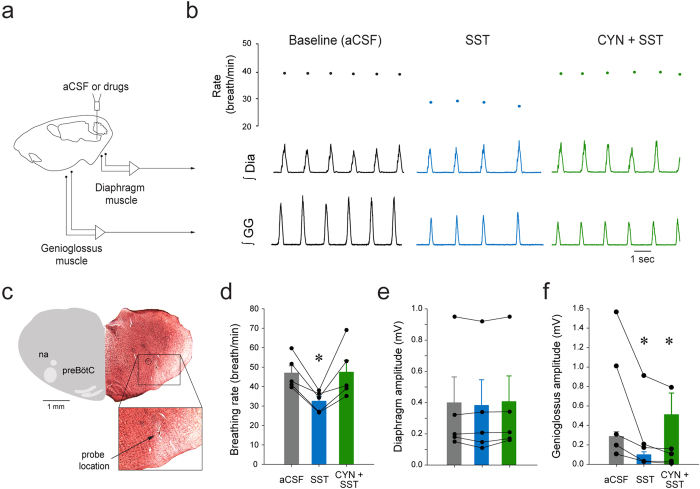

SST and respiratory activity in vivo

The inhibitory peptide SST is co-expressed with NK-1R in a large proportion of preBötC8. Inhibition of SST-expressing neurons abolishes rhythmic breathing in rats11 and application of SST in the preBötC of adult rats decreases breathing rate31. Although SST-expressing neurons project to hypoglossal premotor neurons5, their functional role in modulating genioglossus muscle amplitude has not been determined. In anesthetised rats, microperfusion of SST (200 μM) into the preBötC (Fig. 6a) decreased respiratory rate and genioglossus muscle activity (Fig. 6b). Histology confirmed that the probe was located ventral to the nucleus ambiguus and in the region of the preBötC (Fig. 6c). In 5 rats, SST slowed respiratory rate by 27.3 ± 8.8% (P = 0.014, n = 5, Fig. 6d). This inhibition was blocked by concomitant microperfusion of the SST2 receptor antagonist CYN-154806 (100 μM). Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not significantly changed by SST or CYN-154806 at the preBötC (P = 0.105, n = 5, Fig. 6e). SST decreased genioglossus muscle amplitude by 38.9 ± 25.3% (P = 0.038, n = 5, Fig. 6f), but this inhibition was unaffected by CYN-154806 at the preBötC (P = 0.732, n = 5). These results identified that SST inhibited breathing rate via SST2 receptors, whereas it decreased genioglossus muscle amplitude via another non-SST2 receptors.

Figure 6. Modulation of rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude by SST and SST2 receptors in anesthetized rats.

Microperfusion of SST (200 μM) into the preBötC (a) depressed rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude (b), reduction that were blocked by the SST2 receptor antagonist CYN-154806 (20 μM, b). Dots indicate breathing rate for each breath. The microperfusion probe was located ventral to the nucleus ambiguus in the preBötC region (c). SST decreased breathing rate (n = 5, d) and CYN-154806 blocked the inhibition by SST. Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not changed by SST or CYN-154806 (e). SST also diminished significantly genioglossus muscle amplitude and this decrease was not blocked by the SST2 receptor antagonist (f). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal. SST, somatostatin. CYN, the SST2A antagonist CYN-154806.

SST4 receptors and genioglossus muscle activity

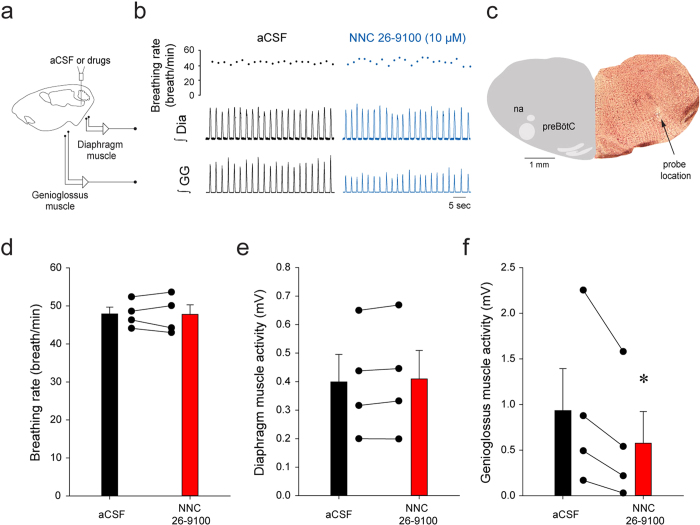

To identify the type of SST receptors regulating inhibition of genioglossus muscle activity by SST, we perfused the SST4 receptor agonist NNC 26–910032 into the preBötC (Fig. 7a). There is currently no available antagonist that is selective for SST4 receptors. NNC 26–9100 (10 μM) did not change breathing rate (Fig. 7b–d, P = 0.902) or diaphragm muscle amplitude (Fig. 7e, P = 0.092), but significantly reduced genioglossus muscle activity by 54.9 ± 27.7% (P = 0.048, Fig. 7f). These results showed that activation of SST4 receptors in the preBötC inhibited genioglossus muscle activity, without affecting breathing rate and diaphragm amplitude.

Figure 7. SST4 receptor activation at the preBötC did not change rhythmic breathing but decreased genioglossus muscle amplitude in anesthetized rats.

Microperfusion of the SST4 receptor antagonist NNC 26–9100 (10 μM) into the preBötC of anaesthetized rats (a) decreased genioglossus muscle activity but not breathing rate and diaphragm amplitude (b). The microperfusion probe was located in the preBötC ventral to the nucleus ambiguus (c). NNC 26–9100 (10 μM) into the preBötC did not significantly change breathing rate (d) or diaphragm muscle amplitude (e), but significantly reduced genioglossus muscle amplitude (n = 4, f). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal.

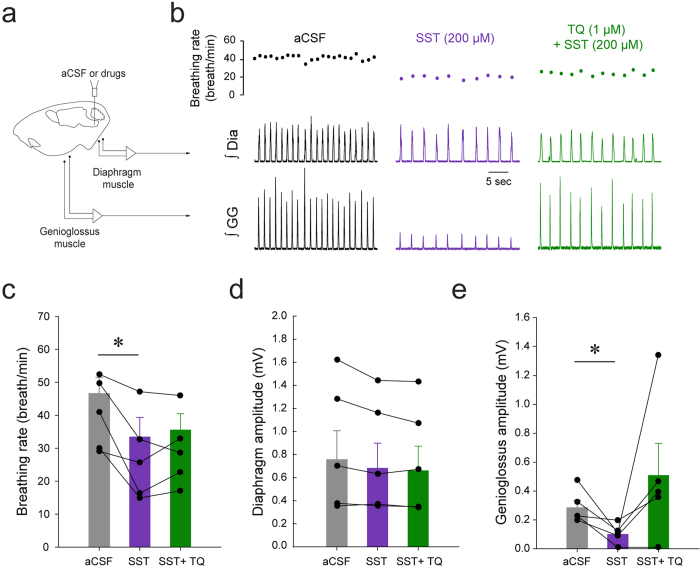

SST and GIRK channels

SST, through binding to its cognate receptors, inhibits glutamate release by activating potassium leak current or inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium current19. Because SST, MOR, and NK-1R are co-expressed in the same cells, these GPCRs may share similar mechanisms to modulate neuronal activity. We therefore tested whether GIRK channels regulate inhibition of respiratory activity by SST by blocking in the preBötC GIRK channels using the GIRK channel blocker Tertiapin Q (1 μM). Perfusion of SST to the preBötC (Fig. 8a) decreased breathing rate and genioglossus muscle amplitude, but did not affect diaphragm amplitude (Fig. 8b). In 5 rats, SST significantly decreased breathing rate (Fig. 8c, P = 0.022, n = 5), an effect that was not blocked by Tertiapin Q (P = 0.578, n = 5). Diaphragm amplitude was not affected by SST or Tertiapin Q (Fig. 8d, P = 0.055, n = 5). Genioglossus muscle amplitude was not significantly changed by SST or SST + Tertiapin Q due to the high variability of muscle amplitude (Fig. 8e, P = 0.101, n = 5).

Figure 8. Inhibition of genioglossus muscle amplitude by SST, but not inhibition of breathing rate, was blocked by the GIRK channel blocker Tertiapin Q.

Microperfusion of SST (200 μM) into the preBötC of anaesthetized rats (a) decreased breathing rate and genioglossus muscle activity, but only genioglossus muscle amplitude was reversed by Tertiapin Q (b). SST significantly decreased breathing rate, but Tertiapin Q was not able to block this inhibition (n = 5, c). SST significantly decreased genioglossus muscle amplitude and this depression was reversed by Tertiapin Q (1 μM). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal.

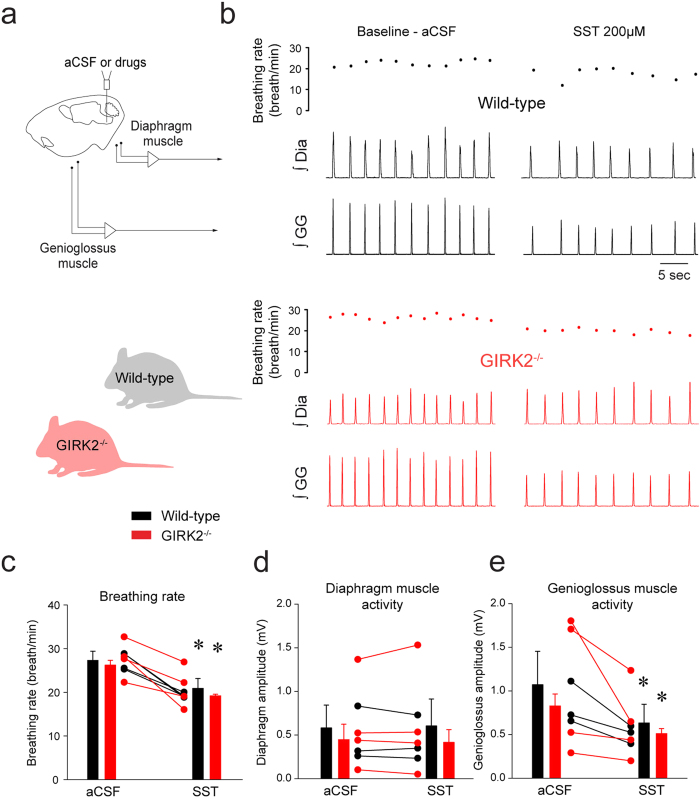

To better assess the contribution of GIRK channels to inhibition of breathing by SST, we perfused SST in wild-type and GIRK2−/− mice (Fig. 9a,b). In wild-type mice, microperfusion of SST into the preBötC decreased breathing rate by 23.3 ± 12.9% (P = 0.040, n = 4, Fig. 9c). Diaphragm muscle activity was unchanged by SST (P = 0.668, n = 4, Fig. 9d). SST did not decrease genioglossus muscle activity (P = 0.171, n = 4, Fig. 9e). In GIRK2−/− mice, SST decreased breathing rate by 26.5 ± 6.8% (P = 0.036). Two-way ANOVA showed that there was no interaction between genotype x conditions (P = 0.824, n = 4), therefore showing that SST decreased breathing rate in GIRK2−/− mice. Diaphragm muscle activity was also not differently changed by SST in wild-type and GIRK2−/− mice (P = 0.438). SST also significantly decreased genioglossus muscle activity in GIRK2−/− mice by 36.9 ± 9.4% (P = 0.021) and there was no interaction between genotype and conditions (P = 0.698). We also assessed whether breathing rate in wild-type and GIRK2−/− differed in males and females. A 2-way ANOVA showed that females, males wild-type and GIRK2−/− present similar breathing rate (genotype x sex, P = 0.648, n = 8 males and n = 9 females). In summary, these results demonstrate that reduction of respiratory activity by SST was not dependent on GIRK channels.

Figure 9. SST decreased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude in the wild-type and GIRK2−/− mice.

Microperfusion of SST (200 μM) into the preBötC (a) significantly increased breathing rate in wild-type mice (b) and in GIRK2−/− mice. Mean data showed that breathing rate was decreased wild-type (n = 4) and GIRK2−/− mice (n = 4, c). Diaphragm muscle amplitude was not changed by SST either in wild-type nor in GIRK2−/− mice (d). Genioglossus muscle amplitude was decreased by SST in wild-type, but not in GIRK2−/− mice (e). *Indicate mean values significantly different from aCSF/baseline with P < 0.05. Data are indicated as means ± S.E.M and as individual values for each animal.

Discussion

Understanding the structural and functional organization of the neural circuits generating rhythmic breathing and upper airway muscle activity is essential to comprehend how breathing is generated. At the core of the respiratory network, preBötC neurons co-express NK-1Rs, SST, and MORs, and project to hypoglossal premotor areas3,5 driving the hypoglossal motor pools and genioglossus muscle activity. Although the identities of preBötC neurons essential for rhythmic breathing have been established, the functional roles of NK-1Rs and SST receptors in regulating rhythmic breathing and upper airway muscle activity are unknown. Here, we first established that NK-1R activation in the preBötC increases rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity. Conversely, SST reduces rhythmic breathing by activating SST2 receptors. Interestingly, SST4 receptor activation decreases genioglossus muscle activity, but not breathing rate, therefore suggesting that SST4 receptors may mediate the SST-induced changes in motor output. We further explored the underlying mechanisms mediating respiratory activity in the preBötC and identified that GIRK channels modulate NK-1R stimulation of rhythmic breathing and upper airway muscle activity, but not inhibition by SST.

GIRK channels and preBötC

GIRK2 subunits, which contribute to forming 3 out of 4 types of GIRK channels, were expressed in the region of the preBötC. Importantly, a subpopulation of GIRK2-expressing neurons also expressed NK-1Rs. In mice, GIRK2 subunits were also found in the preBötC region17. Small fusiform preBötC interneurons express NK-1R and SST8 and are thought to be the site of respiratory rhythm generation in rodents7. Hence cells co-expressing GIRK2 and NK-1Rs may constitute a subpopulation of the small fusiform NK-1R/SST important for the generation of rhythmic breathing33.

Functional role of GIRK channels

The anatomical location, the identity of the cells expressing GIRK2 subunits, and our previous data17 suggests that GIRK channels in preBötC cells are essential components of the neural circuit modulating breathing. To further test this concept we manipulated GIRK channels in the preBötC region of adult rats and measured the subsequent changes in respiratory activity. Our results showed that GIRK channel activation at the preBötC decreased rhythmic breathing, a result that was previously identified17. Importantly, we further identified that GIRK channels decreased genioglossus muscle activity. Flupirtine decreased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle amplitude in wild-type, but not in GIRK2−/− mice17, suggesting that flupirtine inhibited breathing selectively through GIRK channels in vivo. In summary, we identified that activation of GIRK channels in the preBötC region diminished respiratory rhythm, and most importantly, motor output.

NK-1Rs and GIRK channels

Substance P, a peptide that binds to NK-1Rs, NK-2Rs, and NK-3Rs, increased phrenic nerve frequency in rabbits25 and rats31, but the NK-1R agonist GR73632 did not stimulate rhythmic breathing in rabbits25. These results are not consistent with the clear role of NK-1Rs in generating rhythmic breathing in vivo7,34, and our results showing that selective activation of NK-1Rs in the preBötC region increased rhythmic breathing. In addition to increase rhythmic breathing, NK-1R activation also increased genioglossus muscle activity. This result is consistent with NK-1R-expressing preBötC cells projecting directly to premotor hypoglossal neurons33. Similarly, application of substance P to the preBötC increased rhythmic breathing and hypoglossal motor output in vitro16. We then further explored the contribution of GIRK channels to NK-1R-related increase in respiratory activity. We identified that NK-1R activation did not significantly increase breathing rate and motor output in mice lacking GIRK2−/− subunits compared to wild-type animals, a result suggesting that NK-1Rs stimulate neuronal activity via inhibition of GIRK channels, although the direct link between NK-1Rs and GIRK channels remains to be specifically demonstrated.

SST receptors and respiratory activity

SST-expressing preBötC cells are essential for the generation of breathing in adult rats in vivo11 and application of SST to the medulla decreases rhythmic breathing31. PreBötC interneurons are thought to generate rhythmic breathing, but a sub-population of follower SST preBötC neurons also project to premotor hypoglossal neurons33. Rhythmogenic preBötC interneurons are derived from a set of precursors that express the homeobox gene Dbx14. Interestingly, Dbx1-expressing preBötC neurons also co-expressed SST2A receptors9 and regulate hypoglossal motor output3. The existence of subpopulations of SST preBötC neurons suggests that SST may play different functional roles in modulating respiratory rhythm and motor output. In the present study, SST into the preBötC decreased rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity. Interestingly, SST2 receptor blockade reversed the effect of SST on rhythmic breathing, but not on genioglossus muscle activity, a finding consistent with the role of SST2A receptors in vitro9. On the other hand, SST4 receptor activation only decreased genioglossus muscle activity. Due to the lack of available selective SST4 receptor antagonist, the role of SST4 receptors in mediating SST-related reduction of genioglossus muscle activity cannot be tested. Furthermore, respiratory inhibition by SST was not mediated by GIRK channels suggesting that different mechanisms may mediate respiratory inhibitions by SST and MOR17. Overall, these results highlight two receptor subtypes underlying SST-mediated inhibition of respiratory network activity. SST at the preBötC inhibits rhythmic breathing via SST2 receptors, whereas SST may inhibit genioglossus muscle activity via SST4 receptors.

NK-1R excitation and MOR inhibition

The relationship between MORs and NK-1Rs keeps the balance between nociception and analgesia, with activation of MORs inhibiting the release of neurotransmitters involved in nociception, therefore reducing neurotransmission related to pain35. Similarly, NK1-R-expressing preBötC neurons are preferentially inhibited by MOR agonists14. Activation of NK-1Rs increases rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity, whereas inhibition by MORs decreases them14,15. Importantly, GIRK channels contribute to respiratory inhibition by MORs17 and respiratory stimulation by NK-1Rs. Here we propose that GIRK channels in the preBötC maintain the balance between inhibitory and excitatory GPCRs and stabilize breathing (Montandon et al.17). When such balance is altered, for instance by opioid drugs, then breathing is depressed36,37. Likewise central apneas can occur following destruction of NK-1R-expressing preBötC cells in animals34 or in patients with multiple lateral sclerosis38. Overall, identification of GIRK channels as an important component of the respiratory circuitry that maintains stable breathing is central to understanding respiratory network function and dysfunction.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Montandon, G. et al. Contribution of the respiratory network to rhythm and motor output revealed by modulation of GIRK channels, somatostatin and neurokinin-1 receptors. Sci. Rep. 6, 32707; doi: 10.1038/srep32707 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kevin Wickman (University of Minnesota) for providing the original GIRK2 breeders. Research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP. R.L.H.) and the National Sanitarium Association (R.L.H.). G.M. was supported by a Parker B. Francis Fellowship.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Experiments were performed at the University of Toronto (Toronto, ON, Canada). G.M. designed, acquired, analysed, drafted and revised the manuscript. H.L. acquired, analysed, drafted and revised manuscript. R.L.H. designed, drafted, and revised the manuscript. All authors approved final version, agreed to the accountable, and qualified for authorship.

References

- Smith J. C., Ellenberger H. H., Ballanyi K., Richter D. W. & Feldman J. L. Pre-Botzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 254, 726–729 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi H. et al. Functional imaging, spatial reconstruction, and biophysical analysis of a respiratory motor circuit isolated in vitro. J. Neurosci. 28, 2353–2365 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill A. L. et al. Dbx1 precursor cells are a source of inspiratory XII premotoneurons. eLife 4, doi: 10.7554/eLife.12301 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Laser ablation of Dbx1 neurons in the pre-Botzinger complex stops inspiratory rhythm and impairs output in neonatal mice. eLife 3, e03427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Pagliardini S., Yang P., Janczewski W. A. & Feldman J. L. Projections of preBotzinger Complex neurons in adult rats. J Comp Neurol 518, 1862–1878 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. A., Wang X. & Del Negro C. A. Cumulative lesioning of respiratory interneurons disrupts and precludes motor rhythms in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 8286–8291 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray P. A., Janczewski W. A., Mellen N., McCrimmon D. R. & Feldman J. L. Normal breathing requires preBotzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 927–930 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta R. L. et al. A group of glutamatergic interneurons expressing high levels of both neurokinin-1 receptors and somatostatin identifies the region of the pre-Botzinger complex. J. Comp Neurol. 455, 499–512 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray P. A. et al. Developmental origin of preBotzinger complex respiratory neurons. J Neurosci 30, 14883–14895, 4883 [pii] (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. B., Hedner T. & Hedner J. Local application of somatostatin in the rat ventrolateral brain medulla induces apnea. J Appl Physiol 69, 2233–2238 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. et al. Silencing preBotzinger complex somatostatin-expressing neurons induces persistent apnea in awake rat. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 538–540 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupal S. et al. Testing the role of preBotzinger Complex somatostatin neurons in respiratory and vocal behaviors. Eur J Neurosci 40, 3067–3077 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzke T. et al. 5-HT4(a) receptors avert opioid-induced breathing depression without loss of analgesia. Science 301, 226–229 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G. et al. PreBotzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons mediate opioid-induced respiratory depression. J Neurosci 31, 1292–1301 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellen N. M., Janczewski W. A., Bocchiaro C. M. & Feldman J. L. Opioid-induced quantal slowing reveals dual networks for respiratory rhythm generation. Neuron 37, 821–826 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray P. A., Rekling J. C., Bocchiaro C. M. & Feldman J. L. Modulation of respiratory frequency by peptidergic input to rhythmogenic neurons in the preBotzinger complex. Science 286, 1566–1568 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G. et al. G-protein-gated Inwardly Rectifying Potassium Channels Modulate Respiratory Depression by Opioids. Anesthesiology, 124(3), 641–50 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajic D., Koike M., Albsoul-Younes A. M., Nakajima S. & Nakajima Y. Two different inward rectifier K+ channels are effectors for transmitter-induced slow excitation in brain neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 14494–14499 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban S. C. & Tallent M. K. Interneuron Diversity series: Interneuronal neuropeptides–endogenous regulators of neuronal excitability. Trends in neurosciences 27, 135–142 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorini S., Liao Y. J., Duncan S. A., Jan L. Y. & Stoffel M. Normal cerebellar development but susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking G protein-coupled, inwardly rectifying K+ channel GIRK2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 923–927 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C. & Slesinger P. A. Emerging roles for G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 11, 301–315 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G. & Horner R. L. State-dependent contribution of the hyperpolarization-activated Na+/K+ and persistent Na+ currents to respiratory rhythmogenesis in vivo. J Neurosci 33, 8716–8728 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. & Watson C. Paxinos and Watson’s The rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Vol. Ed. 7 (Elevier Academic Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Feniuk W., Jarvie E., Luo J. & Humphrey P. P. Selective somatostatin sst(2) receptor blockade with the novel cyclic octapeptide, CYN-154806. Neuropharmacology 39, 1443–1450 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F., Mutolo D., Cinelli E. & Pantaleo T. Neurokinin receptor modulation of respiratory activity in the rabbit. Eur.J Neurosci. 27, 3233–3243 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. F. K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th edn, (Academic Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Klinger F. et al. Concomitant facilitation of GABAA receptors and KV7 channels by the non-opioid analgesic flupirtine. Br J Pharmacol 166, 1631–1642 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne N. N. et al. Flupirtine, a nonopioid centrally acting analgesic, acts as an NMDA antagonist. General pharmacology 30, 255–263 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K. et al. ML297 (VU0456810), the first potent and selective activator of the GIRK potassium channel, displays antiepileptic properties in mice. ACS chemical neuroscience 4, 1278–1286 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong A. Y. & Potts J. T. Neurokinin-1 receptor activation in Botzinger complex evokes bradypnoea. J Physiol 575, 869–885 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. B., Engberg G., Hedner T. & Hedner J. Antagonistic effects of somatostatin and substance P on respiratory regulation in the rat ventrolateral medulla oblongata. Brain Res 556, 13–21 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J. P. et al. Drug design at peptide receptors: somatostatin receptor ligands. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN 18, 15–27, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X. Y., Zhao Y., Wong-Riley M. T., Ju G. & Liu Y. Y. Synaptic relationship between somatostatin- and neurokinin-1 receptor-immunoreactive neurons in the pre-Botzinger complex of rats. J Neurochem 122, 923–933 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay L. C., Janczewski W. A. & Feldman J. L. Sleep-disordered breathing after targeted ablation of preBotzinger complex neurons. Nat.Neurosci. 8, 1142–1144 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafton J. A., Abbadie C., Marchand S., Mantyh P. W. & Basbaum A. I. Spinal opioid analgesia: how critical is the regulation of substance P signaling? J Neurosci 19, 9642–9653 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A., Aarts L. & Smith T. W. Incidence, Reversal, and Prevention of Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression. Anesthesiology 112, 226–238 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G. & Horner R. CrossTalk proposal: The preBotzinger complex is essential for the respiratory depression following systemic administration of opioid analgesics. J Physiol 592, 1159–1162 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher S. W., Rub U. & Deller T. Neuroanatomical characteristics of the human pre-Botzinger complex and its involvement in neurodegenerative brainstem diseases. Brain: a Journal of Neurology 134, 24–35 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]