Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate and compare the characteristics of court verdicts on medical errors allegedly harming patients in Spain and Massachusetts from 2002 to 2012.

Design, setting and participants

We reviewed 1041 closed court verdicts obtained from data on litigation in the Thomson Reuters Aranzadi Westlaw databases in Spain (Europe), and 370 closed court verdicts obtained from the Controlled Risk and Risk Management Foundation of Harvard Medical Institutions (CRICO/RMF) in Massachusetts (USA). We included closed court verdicts on medical errors. The definition of medical errors was based on that of the Institute of Medicine (USA). We excluded any agreements between parties before a judgement.

Results

Medical errors were involved in 25.9% of court verdicts in Spain and in 74% of those in Massachusetts. The most frequent cause of medical errors was a diagnosis-related problem (25.1%; 95% CI 20.7% to 31.1% in Spain; 35%; 95% CI 29.4% to 40.7% in Massachusetts). The proportion of medical errors classified as high severity was 34% higher in Spain than in Massachusetts (p=0.001). The most frequent factors contributing to medical errors in Spain were surgical and medical treatment (p=0.001). In Spain, 98.5% of medical errors resulted in compensation awards compared with only 6.9% in Massachusetts.

Conclusions

This study reveals wide differences in litigation rates and the award of indemnity payments in Spain and Massachusetts; however, common features of both locations are the high rates of diagnosis-related problems and the long time interval until resolution.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, FORENSIC MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Patient safety has been developed from several perspectives: health, economic, ethics and legal issues. However, there is wide variation in how different countries implement patient safety policies in healthcare, and how the legal system is involved in the patient safety setting.

This is the first study that evaluates and compares the relationship between court verdicts in different healthcare and judicial systems involving medical errors.

In both locations, only a small proportion of court verdicts involved injury-producing medical errors.

The probability of receiving economic compensation for a medical error adjudicated in court was markedly higher in Spain than in Massachusetts, and the number of providers involved in Massachusetts was higher than in Spain.

The main limitation of our study is the research of the outcomes of closed verdicts in court involving injury-producing medical errors. Therefore, we did not investigate any agreements or settlements.

Introduction

When something goes wrong in healthcare, the event is occasionally litigated, resulting in a final verdict.1–4 Several studies underscore the need for new approaches to patient safety through the legal-judicial setting.5–7 One interpretation of patient safety involves understanding how the tort law works in order to comprehensively identify malpractice lawsuits, the size of indemnity payments or the effectiveness of litigation as a mechanism for dispute resolution. Consequently, various strategies could improve healthcare safety and limit litigation while decreasing the economic and social costs resulting from medical errors.8–12

Currently, under administrative compensation for medical injuries, lawsuits need to prove that there is damage and that it was causally related to medical care because a standard of care was breached in the healthcare setting. This type of system is often called the ‘no fault system’ because the claimant must prove that the injury was caused by factors related to the health setting rather than by the provider's negligence. Examples of geographical regions with this model are Denmark, Sweden and Spain, and recently the states of Florida and Virginia in the USA for serious injuries.13 In contrast, most medical injury suits in the USA are assessed in the civil court and, to receive compensation, the plaintiff must prove that the health provider was negligent. This system focuses on the actions of health professionals rather than the health setting, not taking into account factors determining the safety of the healthcare system such as institutional context, organisation and management or work environment. For this reason, the law demands the exercise of due care consistent with any contractual relationship between parties such as providers and patients and factors related to the organisation, such as a lack of procedures or human resource, are not involved in the review of the process.14–16

The patient safety movement has been developed from distinct perspectives, covering health, economic, ethical and legal issues. However, there is wide variation in how different countries implement patient safety policies in healthcare, and how the legal system is involved in the patient safety setting.17–20 The systems in Spain (Europe) and Massachusetts (USA) differ with respect to patient safety policies in their respective health and legal settings. Massachusetts, under federal and state court, resolves malpractice suits in civil court for all settings where the injury was caused by negligent medical management. Mandatory reporting systems, medication education programmes, or leadership quality and safety committees are crucial for advancing quality and safety efforts in healthcare. In contrast, Spain recently developed patient safety policies in its healthcare system, with no specific regulation on safety, and has a voluntary reporting system for adverse events, assessing medical injury associated with the taxpayer-funded health system by using an administrative compensation model or ‘no fault system’. Consequently, the occurrence of medical errors in these health systems and their assessment by the legal-justice settings can be compared, providing a wealth of information that is relevant to understanding patterns of error, patient injury and their impact on health policies.21–24 It could know how the civil court in Massachusetts and ‘no fault system’ in Spain resolved medical errors according to severity and, main causes of injuries, and the time between medical error and the verdict or numbers of patients, health professionals implicated or the economic compensation awarded. Policymakers, providers, patients and lawyers could thus identify many of the elements of their countries' systems that could advance patient safety challenges.25 26

The aim of this study was to assess and compare the characteristics and outcomes of medical errors leading to lawsuits being resolved in courts in Spain (no fault system) and Massachusetts (civil court) between 2002 and 2012.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

To obtain data on litigation in Spain, we used the Thomson Reuters Aranzadi Westlaw databases, which provide records on all closed claims adjudicated in court nationwide. Hence, these data provide information on lawsuits resolved in a courtroom setting by ‘no fault system’. This database includes 1041 closed verdicts involving the health system between 2002 and 2012. For Massachusetts, data were obtained from the Controlled Risk Insurance Company and Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions (CRICO/RMF) in Cambridge (Massachusetts, USA). CRICO/RMF represents the largest medical professional liability carrier in Massachusetts and provides industry-leading medical professional liability coverage, claims management and patient safety resources to the Harvard medical community. We identified 370 closed verdicts in this database involving the health system by the civil court.

After reviewing the methods used in previous studies related to medical malpractice research,1 2 14 for this study medical errors were defined according to the Institute of Medicine as ‘the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim, as an error of execution or as an error of planning’.27

Verdicts were reviewed by one researcher, first to identify those that could have involved a medical error and second to determine whether a medical error had occurred. If so, the researcher analysed the characteristics and outcomes of the error. The following variables were collected: number and date of the court verdict, date of medical injury, number of plaintiffs and defendants (no data on demographic characteristics were available), characteristics of the medical error and the compensation awarded by the court. The Clinical Coding of Risk Management Foundation of Harvard Medical Institutions in Cambridge (Massachusetts, USA) was used, which includes information on injury severity and contributory factors. A severity rating scale of the outcomes of the alleged injury was derived from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, which contains a scale from 0 to 9. The contributory factors represented the reason for the injury and were coded by using three categories (low, medium and high) and nine subcategories (emotional, temporary insignificant, temporary minor, temporary major, permanent minor, permanent significant, permanent major, permanent grave and death).

Exclusion criteria

For the present study, we excluded verdicts on injuries occurring in prisons, work-related accidents in health centres and failures of the informed consent process, and we did not include any agreements between parties before a judgement.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of the medical errors identified was conducted, stratified by severity, the main causes and the locations studied. The prevalence and percentages of court verdicts on injury-producing medical errors in Spain and Massachusetts, as well as their 95% CIs, were calculated. Prevalence and percentages were compared with the χ2 test. We also calculated the percentage ratio and 95% CI by location (Spain vs Massachusetts) of high-severity medical errors according to cause. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Software V.18.

Results

Characteristics of court verdicts involving medical errors

Closed court verdicts involving medical errors represented 25.9% of 1041 closed court verdicts in Spain versus 75% of 370 closed court verdicts in Massachusetts.

As shown in table 1, the severity and contributory factors differed significantly between the two locations, although most medical errors were rated as medium or high severity (87.4% in Spain and 96.8% in Massachusetts). The most frequent cause was a diagnosis-related problem (25.1%; 95% CI 20.7% to 37.1% in Spain and 35%; 95% CI 29.4% to 40.7% in Massachusetts). The number of medical errors associated with surgical and medical treatment was higher in Spain than in Massachusetts.

Table 1.

Severity level and main causes of medical errors resolved by court in Spain and Massachusetts

| Spain | Massachusetts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % (95%CI) | % (95%CI) | p-value | |

| n=270 | n=274 | ||

| Severity | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 12.6 (8.6 to 16.6) | 3.3 (1.2 to 5.4) | |

| Medium | 28.5 (23.1 to 33.9) | 29.6 (24.2 to 35.0) | |

| High | 58.9 (53.0 to 64.8) | 67.2 (61.6 to 72.8) | |

| Contributory factors | 0.001* | ||

| Medical treatment | 19.3 (14.6 to 24.0) | 10.6 (6.9 to 14.2) | |

| Obstetrics-related treatment | 15.9 (11.6 to 20.3) | 11.7 (7.9 to 15.5) | |

| Surgical treatment | 22.2 (17.3 to 27.2) | 21.9 (17.0 to 26.8) | |

| Anaesthesia-related treatment | 1.8 (0.2 to 3.5) | 4.0 (1.7 to 6.3) | |

| Diagnosis-related | 25.2 (20.7 to 31.1) | 35.0 (29.4 to 40.7) | |

| Medication-related | 4.4 (2.0 to 6.9) | 7.7 (4.5 to 10.8) | |

| Others | 10.0 (6.4 to 13.6) | 9.1 (5.7 to 12.5) |

*χ2 Test.

As shown in table 2, the percentage of medical errors rated as high severity differed significantly in the two locations (54.4% in Spain and 82.2% in Massachusetts; percentage ratio: 0.66; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.96). In Spain, the percentage of medical errors due to diagnosis-related problems (failure, delay or mistaken diagnosis) that were rated as high severity was 34% lower than in Massachusetts. For other causes, the percentage of high-severity medical errors was 15% lower in Spain than in Massachusetts, but this difference was not statistically significant. The distribution of medical errors rated as high severity in the remaining causes was similar between the two locations (all percentage ratios were near unity).

Table 2.

High severity in according to causes of medical errors adjudicated in court

| Causes | Spain |

Massachusetts |

Both |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 95% CI | n (%) | 95% CI | PR* | 95% CI | |

| Obstetrics-related treatment | 33 (76.7) | 64.1 to 89.4 | 24 (75.0) | 60.0 to 90.0 | 1.02 | 0.61 to 1.80 |

| Surgical treatment | 30 (50.0) | 37.3 to 62.7 | 29 (48.3) | 35.7 to 60.9 | 1.03 | 0.62 to 1.75 |

| Medical treatment | 36 (69.2) | 56.7 to 81.8 | 19 (65.5) | 47.9 to 82.5 | 1.05 | 0.63 to 1.98 |

| Diagnosis-related | 37 (54.4) | 42.3 to 65.9 | 79 (82.3) | 75.4 to 90.4 | 0.66 | 0.43 to 0.96 |

| Others | 23 (48.9) | 34.6 to 63.2 | 33 (57.9) | 45.1 to 70.7 | 0.85 | 0.48 to 1.42 |

*PR, prevalence ratio.

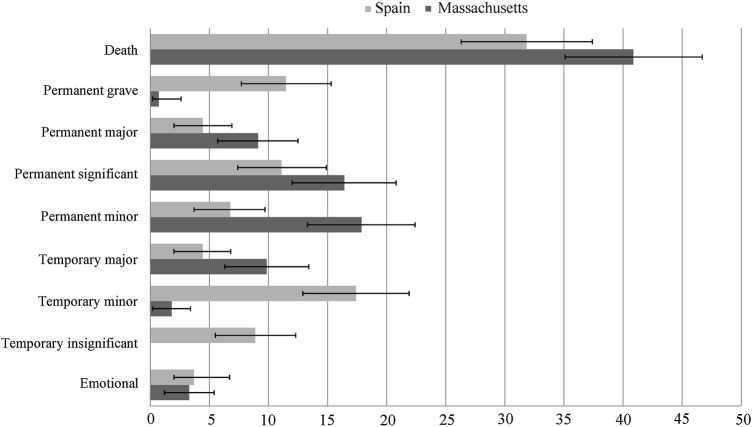

As shown in figure 1, a high percentage of medical errors had a fatal outcome in both locations (31.8% in Spain and 40.8% in Massachusetts, p<0.001). There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to permanent grave adverse outcome (11.4% vs 0.7%), temporary minor adverse outcome (17.4% vs 1.8%) and temporary insignificant adverse outcomes (8.8% vs 0%) in Spain versus Massachusetts, respectively. Temporary minor and permanent minor adverse outcomes were rated as medium severity, but their consequences are starkly different: a temporary minor severity adverse outcome is equivalent to an infection, fracture or delayed recovery, whereas a permanent minor severity adverse outcome means loss or damage to organs.

Figure 1.

Percentage of medical errors resolved by court.

Surgical treatment was associated with 56.6% of medical errors in Spain and with 53.3% in Massachusetts. Improper management of surgical patients was associated with 30% and 33.3% of medical errors, respectively. In Spain, improper management of pregnancy was associated with 55.8% of medical errors, and improper performance of operative delivery with 32.5% of medical errors (p=0.550). In Massachusetts, the main cause of obstetrics-related problems was delay in the treatment of fetal distress (43.7%).

Characteristics of medical errors according to the judicial system

Economic compensation was awarded in 98.5% of court verdicts involving the health system in Spain but in only 6.9% of verdicts in Massachusetts (p<0.001). In Massachusetts, 93.1% of court verdicts on medical errors awarded no compensation. In addition, 24.1% of medical errors rated as high severity in Spain led to payments of <€50 000; of these, payments of >€200 000 were awarded in 23.1%.

As shown in table 3, the mean time interval between the occurrence of the medical error and the final verdict was 7.90 years (SD 3.39; range 1.62–21.7) in Spain and 7.21 years (SD 2.17; range 2.74–19.31) in Massachusetts (p=0.005). The number of plaintiffs (patients or their families) filing a claim for a medical error adjudicated at court was 368 in Spain and 274 in Massachusetts. The number of defendants involved in a medical error adjudicated at court (providers or health institutions) was 276 (mean 1.02) in Spain and was 621 (mean 2.27) in Massachusetts.

Table 3.

Average time, institution, plaintiff and defendant by locations stated

| Spain | Massachusetts | |

|---|---|---|

| Time interval between medical error and the verdict | ||

| Frequency | 257 | 274 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.90 (3.39) | 7.21 (2.17) |

| Median | 7.24 | 7.01 |

| Minimum | 1.62 | 2.74 |

| Maximum | 21.7 | 19.31 |

| Institution | ||

| Frequency | 279 | 123 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.09 (0.41) | 3.00 (0) |

| Median | 1 | 3.00 |

| Minimum | 1 | 3 |

| Maximum | 3 | 3 |

| Plaintiff | ||

| Frequency | 368 | 274 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.36 (0.67) | 1 (0) |

| Median | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 4 | 1 |

| Defendant | ||

| Frequency | 276 | 621 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.02 (0.17) | 2.27 (1.66) |

| Median | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 3 | 12 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that compares court verdicts involving medical errors in two different locations. Over an 11-year period, most court verdicts involving the health system were related to medical errors in Massachusetts. In Spain, the proportion was lower, representing one-fourth of court verdicts involving the health system.

These findings support those of other studies investigating the relationship between claims and medical errors in the USA. For example, one of the first studies showed that 28% of 46 closed malpractice claims over a 1-year period involved an adverse event.1 A study performed at Harvard on medical malpractice suggested that nearly 40% of claims were not associated with medical errors and only 15% of all claims were resolved by court verdicts.1 4 Both these studies evaluated the medical malpractice system in the USA, but did not compare medical errors litigated in distinctly different healthcare and judicial systems such as Spain and Massachusetts.

Our study shows that most court verdicts involved high-severity adverse outcomes, with statistically significant differences between the two locations. Our data indicated many similarities in the factors contributing to medical errors in the two healthcare systems.27–30 Most medical errors were caused by diagnosis-related problems, with statistically significant differences. Diagnosis and medical and surgical treatment could be improved by training using simulations to replicate important aspects of the real world and to change inappropriate medical attitudes.5 31–33 Healthcare stakeholders should consider diagnosis in healthcare a critical health policy issue.34

The probability of receiving economic compensation for a medical error adjudicated in court is markedly higher in Spain than in Massachusetts (98.5% vs 6.9%, respectively). However, unequal compensation was awarded in Spain for events with the same degree of injury. These economic data only reflect compensation awarded by court verdicts and not disputes over medical errors resolved through settlements, mediation or arbitration. Moreover, a study in the USA showed that a substantial minority of physicians were not required to make an indemnity payment after a claim, probably because patients would have difficulty finding an attorney in the tort system because the expected award would not justify his or her investment in the litigation.2 Reforms are therefore needed in the system such that healthcare organisations provide compensation that is fair to equally harmed patients, and a deep sense of individual and institutional accountability for safety, with an emphasis on fairness as providers and patients alike.

The number of providers involved in medical errors adjudicated in court in Massachusetts was higher than in Spain. This was because of the type of judicial system, in which the harmed patient usually sues the provider but not the healthcare institution (an administrative justice model is used in Spain and a civil justice model is used in Massachusetts). Projections from a study in the USA showed that nearly all physicians in high-risk specialties would face at least one malpractice claim during their careers.2 Although these rates are low, they suggest that the risk of being sued alone may create a tangible fear among physicians who work in Massachusetts that is higher than in Spain.2 35 36 For liability insurance, it is possible to use other strategies to promote safety, such as offering financial incentives to physicians and nurses who follow safe practices.26

Finally, the time lapse between the injury and the verdict was excessive in both locations (7.90 years in Spain and 7.21 years in Massachusetts). An unreasonable amount of time and expense was required to deliver compensation and to instigate measures to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare.37 Data from previous studies1 28 suggested an average time interval between the occurrence of the injury and the closure of the claim of 5 years, but the data were not limited to those from court verdicts. In this regard, reforms could improve patient safety through strategies aimed at improving the effectiveness of the judicial system for providers and patients alike.26 38 39

Our study has several limitations. First, we used different databases to collect information on closed court verdicts. In Spain, we used a nationwide database that provides closed court verdicts from a ‘no fault system’, whereas in Massachusetts we used a database from an insurance company that represents a large proportion of all institutional healthcare in Massachusetts and which shows closed court verdicts from civil court. Second, our study investigated the outcomes of closed verdicts in court involving injury-producing medical errors. Therefore, we investigated only a small number of medical errors occurring in the healthcare setting, and even lesser than studies evaluating the outcome of medical errors resolved by agreement or settlement. Third, we evaluated the occurrence of medical errors in two health systems and legal-justice setting with vast differences. Therefore, we used different variables related to effective of both settings, as related to health system (occurrence, main causes, factors contributing, severity) as variables related to legal-justice setting (time interval between medical error and the verdict, numbers of plaintiff and defendants involved or the economic compensation awarded). Fourth, the closed courts verdicts were reviewed by a single researcher, which may have introduced bias in the selection of the files. Fifth, in both locations, patients may have different reasons for filing a claim for possible medical errors occurring during their care. On the other hand, in both locations, the lawsuits resulting in the court verdicts reviewed were filed based on the litigants' expectation of receiving economic compensation. However, given the time interval between filing a claim and the award of compensation, as well as the variability in the amounts awarded, other methods of dispute resolution such as arbitration and mediation should be encouraged.

In conclusion, our estimates provide a glimpse into medical errors leading to litigation in different locations. The information gathered on the low rate of medical errors leading to court files, the high number of diagnosis-related problems, variability in indemnity payments and the time required for resolution could be used to design new approaches to instigate change.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Allen Kachalia for his commentaries of this manuscript and the staff of the Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions, especially Ann Doherty and Kyle Bergquist, for the knowledge and support that they contributed to this project research.

Footnotes

Contributors: PG and XC conceived the study. LS, JMM-S, MC, MS, KD, XC and PG contributed to the design and coordination of the study. PG analysed the data. PG, LS and JMM-S drafted the first manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to the interpretation of the data and successive revisions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version. PG is the principal researcher for the project.

Funding: This project was funded by the Ignacio Larramendi Research Grants 2013 MAPFRE-Foundation, for which PG is the principal researcher. This research was supported by Grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER (RD13/0001/0013).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Mar Medical Research Institute from Barcelona (Spain).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA et al. Claims, errors, and compensations payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:19 10.1056/NEJMsa054479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med 2011;365:629–36. 10.1056/NEJMsa1012370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane C. Policy research perspectives-medical liability claim frequency: a 2007–2008 snapshot of physicians. Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan TA, Sox CM, Burstin HR. Relation between negligent adverse events and the outcomes of medical-malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1963–7. 10.1056/NEJM199612263352606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen K, Oppenheimer C, Leape LL et al. Envisioning patient safety in the year 2025: eight perspectives. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches (Vol. 1: assessment). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43618/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berlinguer N, Wu A. Subtracting insult from injury: addressing cultural expectation in the disclosure of medical error. J Med Ethics 2005;31:106–8. 10.1136/jme.2003.005538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis RQ, Fletcher M. Implementing a national strategy for patient safety: lessons from the National Health Service in England. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:135–9. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boothman RC, Imhoff SJ, Campbell DA Jr.. Nurturing a culture of patient safety and achieving lower malpractice risk trough disclosure: lessons learned and future directions. Front Health Service Manage 2012;28:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murtagh L, Gallagher TH, Andrew P et al. Disclosure-and-resolution programs that include generous compensation offers may prompt a complex patient response. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2681–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mello MM, Boothman RC, McDonald T et al. Communication and resolution programs: the challenges and lessons learned from six early adopters. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:20–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allué N, Chiarello P, Bernal-Delgado E et al. Assessing the economic impact of adverse events in Spanish hospitals by using administrative data. Gac Sanit 2014;28:48–54. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Den Bos J, Rustagi K, Gray T et al. The $17.1 billion problem: the annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:596–603. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mello MM, Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Administrative compensation for medical injuries: lessons from three foreign systems. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2011;14:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pegalis SE, Bal S. Closed medical negligence claims can drive patient safety and reduce litigation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:1398–404. 10.1007/s11999-012-2308-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giraldo P, Castells X. Responsibility for reporting adverse events: can notifying health professional be assured? Med Clin (Barc) 2012;139:109–11. 10.1016/j.medcli.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wachter RM, Provonost PJ. Balancing “no blame” with accountability in patient safety. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1401–6. 10.1056/NEJMsb0903885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM et al. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:216.–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kachalia A, Mello MM. New directions in medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1564–72. 10.1056/NEJMhpr1012821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantor MD, Barach P, Derse A et al. Disclosing adverse events to patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2005;31:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López L, Weissman JS, Schneider EC et al. Disclosure of hospital adverse events and its association with patients’ ratings of the quality of care. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1888–94. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budetti PP. Tort reform, and the patient safety movement: seeking common ground. JAMA 2005;293:2660–2. 10.1001/jama.293.21.2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scurr JR, Brigstocke JR, Shields DA et al. Medicolegal claims following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the UK and Ireland. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:286–91. 10.1308/003588410X12664192076214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovit RL, Simon AS, Drew J et al. Neurosurgical experience with malpractice litigation: an analysis of closed claims against neurosurgeons in New York State, 1999 through 2003. J Neurosurg 2007;106:1108–14. 10.3171/jns.2007.106.6.1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osman NI, Collins GN. Urological litigation in the UK National Health Service (NHS): an analysis of 14 years of successful claims. BJU Int 2011;108:162–5. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R et al. Liability claims and cost before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:213–21. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mello MM, Gallagher TH. Malpractice reform—opportunities for leadership by health care institutions and liability insurers. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1353–6. 10.1056/NEJMp1001603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips RL, Bartholomew LA, Dovey SM et al. Learning from malpractice claims about negligent, adverse events in primary care in the United States. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:121–6. 10.1136/qshc.2003.008029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aranaz-Andrés JM, Aibar-Remón C, Vitaller-Burillo J et al. Impact and preventability of adverse events in Spanish public hospitals: results of the Spanish National Study of Adverse Events (ENEAS). Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:408–14. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arriaga AF, Bader AM, Wong JM et al. Simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. N Engl J Med 2013;368:246–53. 10.1056/NEJMsa1204720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzano D, Hammoud M, Smith R et al. Implementing new clinical practice guidelines: an ideal use of simulation. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:19 10.1097/01.AOG.0000447274.20508.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballangrud R, Hall-Lord ML, Hedelin B et al. Intensive care unit nurses’ evaluation of simulation used for team training. Nurs Crit Care 2014;19:175–84. 10.1111/nicc.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh H, Graber L. Improving diagnosis in health care. The next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2493–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1512241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baltic S. Tort reform. While some states have taken action to cap damages, fear of litigation still drives defensive medicine. Med Econ 2013;90:20–2, 24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kachalia A, Mello MM. Defensive medicine—legally necessary but ethically wrong? Inpatient stress testing for chest pain in low-risk patients. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1056–7. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson WG, Brennan TA, Newhouse JP et al. The economic consequences of medical injuries. Implications for a no-fault insurance plan. JAMA 1992;267:2487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mello MM, Brennan TA. The role of medical liability reform in federal health care reform. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1–3. 10.1056/NEJMp0903765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sloan FA, Mergenhagen PM, Bovbjerg RR. Effects of tort reforms on the value of closed medical malpractice claims: a microanalysis. J Health Polit Policy Law 1989;14:663–89. 10.1215/03616878-14-4-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]