Abstract

Background

An obesity subphenotype, named ‘metabolically healthy obese’ (MHO) has been recently defined to characterise a subgroup of obese individuals with less risk for cardiometabolic abnormalities. To date no data are available on participants born with small weight for gestational age (SGA) and the risk of metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUHO).

Objective

Assess the risk of MUHO in SGA versus appropriate for gestational age (AGA) adult participants.

Methods

129 young obese individuals (body mass index ≥30 kg/m²) from data of an 8-year follow-up Haguenau cohort (France), were identified out of 1308 participants and were divided into 2 groups: SGA (n=72) and AGA (n=57). Metabolic characteristics were analysed and compared using unpaired t-test. The HOMA-IR index was determined for the population and divided into quartiles. Obese participants within the first 3 quartiles were considered as MHO and those in the fourth quartile as MUHO. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% CI for being MUHO in SGA versus AGA participants were computed.

Results

The SGA-obese group had a higher risk of MUHO versus the AGA-obese group: RR=1.27 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.6) independently of age and sex.

Conclusions

In case of obesity, SGA might confer a higher risk of MUHO compared with AGA.

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Homogeneous population.

High participation rate which reduces selection bias between appropriate for gestational age (AGA) and small weight for gestational age (SGA).

Participants have completed pubertal development and are not at an advanced age to confound insulin resistance development.

First study to evaluate risk of metabolically unhealthy obesity in obese young adults born SGA versus those born AGA.

Small subgroup of the population and thus might have not had enough power to detect significant differences with regard to metabolic variables.

Introduction

Obesity is a condition frequently accompanied by adverse metabolic outcomes such as hypertension,1–3 insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes4 and dyslipidaemia among others.5 6 However, studies have shown that not all obese individuals display such cardiometabolic abnormalities and a metabolically healthy obese (MHO) phenotype versus a metabolically unhealthy obese (MUHO)7–9 phenotype has been described.

Some studies showed that, unlike MUHO people, MHO particiapnts are not at increased risk of metabolic complications and some studies10–12 but not all,13 14 indicate that they do not show evidence of increased risk of type 2 diabetes, of cardiovascular diseases or even of mortality when compared with metabolically healthy normal weight individuals. The discrepancy in the results seen in different studies might stem from the absence of a precise definition of MHO which varies among studies.9 Why some obese participants can benefit from MHO phenotype is still unclear, but some reasons such as greater metabolic reserve, fitness, increased muscle mass and strength have been proposed.15

Low birth weight and smallness for gestational age (SGA) have both been associated with later higher susceptibility for development of impaired metabolic phenotype such as obesity, hypertension, IR, as well as type 2 diabetes in adulthood. This has been well documented in several studies, raising primarily nutritional inadequacies during fetal and early life.16–20

Data from the Haguenau cohort showed that participants born SGA have a sixfold increase in metabolic syndrome development at the age of 22 when compared with individuals born with appropriate weight for gestational age (AGA).21

To the best of our knowledge, there are no data available comparing metabolic outcomes of obese adults born SGA with obese adults born AGA nor on the risk of a metabolically unhealthy phenotype in the obese SGA population. We hypothesise that since SGA individuals tend to exhibit more unfavourable metabolic outcomes in adulthood, they would also not benefit from a MHO phenotype in case of obesity. On the other hand, obese AGA individuals would have a higher favourable risk of evolution towards MHO in comparison to their SGA counterparts. The objective of this study was to assess the risk of MUHO in obese SGA versus AGA individuals in the French Haguenau cohort. One of the most important interests of the Haguenau cohort is that the recruited participants are young adults who have completed body development. Studying a group of young obese adults could avoid the presence of confounding metabolic or non-metabolic factors that would be present in the case of obesity at an older age.

Methods

Study population

Data were drawn from the Haguenau cohort, a community-based cohort derived from a maternity registry of the metropolitan area of the city of Haguenau (France) with the purpose of investigating the long-term consequences of being born SGA.22 Briefly, the registry included information about all pregnancies and deliveries occurring at the Haguenau maternity hospital from 1971 to 1985 with 80% degree of completeness.

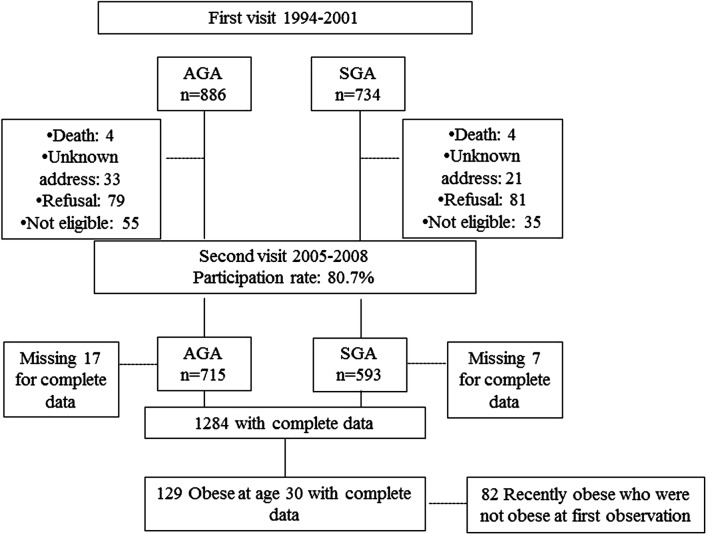

SGA and AGA individuals were all singleton births and born between 32 and 42 weeks of gestation. SGA were individuals born with body weight <10th centile with respect to local standard growth curves, and AGA individuals were born between the 25th and the 75th centiles for sex and gestational age and were selected as the next full-term singleton after the selection of a SGA individual.23 Data in the Haguenau cohort were drawn at two time points. The first visit took place when singletons were on average 22 years of age, and participants who agreed to participate were 886 AGA individuals and 734 SGA.21 The second visit was conducted between April 2005 and December 2008 with a participation rate of 80.7%. A total of 1308 participants thus agreed to participate (593 SGA and 715 AGA) in the cohort. Sensitivity analyses of the missing participants at follow-up (1308 vs 1620) did not disclose any important differences and detailed description about it is available elsewhere.23

For the purpose of this analysis, only obese SGA and AGA individuals at the second visit, when they were on average 30 years old, were included (figure 123).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for study. Adapted from Meas et al.23 AGA, appropriate for gestational age; SGA, small for gestational age.

Measurement strategy: Details about measurements are available in a previous paper.23

Anthropometrics: Weight was measured with a portable scale and height with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Participants attended two visits at the municipal hospital of Haguenau and the same nurses recorded the height and information. Weight for height was assessed as body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and categorised using the WHO classification: underweight <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; overweight 25–29.9 kg/m2 and obese ≥30 kg/m2. One hundred and thirty-two obese individuals (74 SGA and 58 AGA) were thus identified and 129 (69 women and 60 men) with complete data set were included in the analyses (figure 1). Data for waist circumference and percentage of body fat mass were available but not included in the analyses for multicollinearity purposes.

MHO phenotype was determined using the HOMA-IR index for the whole population and using the following formula: (insulin (μU/mL)×glucose (mmol)/22.5). The HOMA-IR index relies on fasting glucose and insulin with higher scores signifying greater IR. Participants were classified as MHO if they belonged to the three first lower quartiles of this index and had a BMI≥30.24

Metabolic variables: Data on fasting serum lipids such as total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), triglyceride and also on plasma glucose and insulin concentration were available and details are included elsewhere.23 Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast for the measurement of serum lipids, plasma glucose and serum insulin concentrations and at the same time of anthropometric measurements. Laboratory procedures, plasma glucose, total cholesterol, HDL-c and triacylglycerol concentrations were measured with enzymatic methods. Serum insulin concentrations were measured using an immunoradiometric method (Bi-insulin IRMA; Cisbio International, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Cross-reactivity with intact proinsulin and des-31, 32 proinsulin was <1%. The detection limit was 3.0 pmol/L and interassay CV was <6.5%. Blood pressure was measured in the right arm of seated individuals after a 30 min rest, using an automated device (Dinamap; Critikon, Neuilly-Plaisance, France) and a cuff of recommended size for the mid-upper arm circumference. Three measurements were made at 1 min intervals and the average of the last two measurements was used in the analysis. All data from blood samples were collected at the same time of anthropometric measurements.

Covariates: Age and sex were determined using the baseline questionnaire. Level of education was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Physical activity was assessed as number of hours of physical activity per week.

All participants gave written consent.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to provide characteristics of the obese SGA-born versus obese AGA-born and are presented as means±SD or percentages as appropriate. A general linear model controlling for age and sex was performed in order to explore the differences in metabolic variables of obese SGA versus AGA individuals. Residual distributions were checked for normality. To determine the relative risk (RR) of MUHO in SGA-obese versus AGA-obese individuals, the SAS Genmod procedure adjusting for age and sex was used. We chose to adjust for age and sex since they were both significant in the models for most of the metabolic variables.

All tests were two-tailed and p<0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were undertaken using SAS V.9.3 software (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study population at birth were previously described in detail.22 23 Briefly, individuals were all born full term and sex distribution did not differ between the AGA and SGA groups. According to the selection criteria, individuals born SGA were lighter (2627±296 vs 3366±274 g), shorter (47.7±2 vs 50.3±1 cm) and thinner (11.6±1.1 vs 13.3±0.8 kg/m2) at birth than individuals born AGA.

Obese AGA-born and SGA-born were similar with regard to age and sex (table 1). No significant difference was observed for physical activity between obese AGA-born and SGA-born individuals.

Table 1.

Obese AGA and SGA characteristics

| Obese AGA | Obese SGA | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 57 (4.4) | 72 (5.6) | |

| Age, years | 29.3 (4.3) | 30.6 (3.7) | 0.10 |

| Male, per cent | 45.6 | 47.2 | 0.72 |

| Socioeconomic status: high level of education, per cent | 31.0 | 24.3 | 0.26 |

| Weight, kg | 100.6 (15.5) | 97.3 (14.7) | 0.17 |

| BMI, height/m2 | 34.4 (4.8) | 34.7 (5.0) | 0.80 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 107.1 (14.2) | 108.0 (12.4) | 0.73 |

| Body fat, per cent | 35.0 (8.7) | 34.7 (9.7) | 0.73 |

| Physical activity, hours/week | 1.0 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.06 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 125.1 (12.4) | 125.0 (13.1) | 0.99 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 76.4 (8.8) | 74.1 (9.5) | 0.14 |

| Total cholesterol, mM | 5.0 (0.8) | 5.2 (1.0) | 0.19; 0.40 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mM | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.03; 0.07 |

| Triglycerides, Mm | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.5) | 0.26; 0.39 |

| Fasting glucose, g/L | 0.91 (0.08) | 0.91 (0.08) | 0.94; 0.65 |

| Fasting insulin, mIU/L | 9.4 (3.8) | 11.0 (4.5) | 0.04; 0.07 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.1 (0.9) | 2.5 (1.0) | 0.05; 0.08 |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

*p Values comparing obese AGA versus obese SGA; the second p values are further adjusted for age and sex for comparison of metabolic variables.

AGA, appropriate for gestational age; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; SGA, small for gestational age.

Significant differences were seen for fasting HDL-c and insulin levels in obese AGA-born versus obese SGA-born, but they disappeared after adjustment for age and sex. Table 2 presents results as a function of HOMA-IR quartiles for obese AGA-born and SGA-born. Quartiles 1, 2 and 3 (Q1, Q2 and Q3) are considered metabolically healthy versus quartile 4 (Q4) considered metabolically unhealthy.

Table 2.

Comparison of metabolic variables in quartiles of HOMA-IR in selected obese AGA and SGA participants at the second visit

| AGA |

SGA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1–Q3: MHO | Q4 | p Value | Q1–Q3: MHO | Q4 | p Value | p1 Value | |

| Age (years) | 28.7 (4.0) | 29.6 (4.5) | 0.45 | 30.4 (4.7) | 30.6 (4.0) | 0.87 | 0.26 |

| Male, per cent | 33.3 | 52.7 | 0.48 | 38.4 | 50 | 0.44 | 0.76 |

| Fasting glucose, g/L | 0.8 (0.08) | 0.9 (0.08) | <0.0001 | 0.8 (0.04) | 0.9 (0.08) | <0.0001 | 1.0 |

| Fasting insulin, mIU/L | 6.2 (1.0) | 11.3 (3.5) | <0.0001 | 5.5 (0.8) | 12.1 (4.1) | <0.0001 | 0.04 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.6 (0.8) | <0.0001 | 1.2 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.9) | <0.0001 | 0.06 |

| Total cholesterol, mM | 4.8 (0.8) | 5.1 (0.8) | 0.17 | 5.0 (0.8) | 5.2 (1.07) | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mM | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Triglycerides, mM | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 0.30 | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.8 (1.5) | 0.06 | 0.52 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 121.8 (9.5) | 127.0 (13.7) | 0.13 | 120.1 (8.8) | 126.1 (13.8) | 0.13 | 0.60 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 76.0 (6.4) | 76.7 (10.2) | 0.77 | 71.3 (6.8) | 74.7 (10.0) | 0.24 | 0.05 |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

p Value next to each group corresponds to a t-test of Q1–Q3 versus Q4 in each group: SGA and AGA.

p1 Value corresponds to t-test for MHO-AGA versus MHO-SGA.

Each p value corresponds to an ANOVA test for each four quartiles.

MHO corresponds to Q1–Q3 in each subgroup (AGA-obese and SGA-obese).

AGA, appropriate for gestational age; ANOVA, analysis of variance; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MHO, metabolically healthy obese; Q, quartile; SGA, small for gestational age.

A significant difference was observed for Q1–Q3 versus Q4 for fasting insulin, glucose and HOMA-IR in both obese SGA-born and AGA-born (Q4 having a higher fasting insulin and glucose levels vs Q1–Q3). However, when comparing MHO-SGA-born (Q1–Q3) versus MHO-AGA-born (Q1–Q3), no significant differences were observed except for fasting insulin which was higher in MHO-AGA-born (Q1–Q3).

Table 3 presents the univariate-adjusted and multivariate-adjusted RRs for MUHO risk in the SGA-born versus AGA-born category. Independently of sex and age, individuals who were obese at the age of 30 and born SGA had an increased risk of MUHO when compared with obese individuals born AGA (RR=1.27; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.6). In a second set of analyses, we also entered socioeconomic status and physical activity in our model as covariates; we still obtained the same results (significantly higher risk of SGA for MUHO; data shown as online supplementary data).

Table 3.

Univariate-adjusted and multivariate-adjusted RRs for MUHO in obese SGA versus obese AGA categories

| MUHO RR (95% CI) |

MUHO RR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Obese at 30 years | Univariate | Multivariate |

| AGA-obese (n=57) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| SGA-obese (n=72) | 1.30 (1.03 to 1.63) | 1.27 (1.01 to 1.60) |

Multivariate analyses adjusted for age and sex.

AGA, appropriate for gestational age; MUHO, metabolically unhealthy obesity; RR, relative risk; SGA, small for gestational age.

bmjopen-2016-011367supp.pdf (45.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

The present study showed that the risk of belonging to the metabolically unhealthy phenotype was highest among young obese adults born SGA compared with their counterparts born AGA.

A total of 66.3% of the population were of normal weight and 10% obese, which is less than the recently reported percentage of obesity (15%) among French adults.25 26

We only found a significant difference in fasting insulin while comparing MHO-SGA versus MHO-AGA showing that MHO-AGA might have a better metabolic health than MHO-SGA. No significant differences were observed for other characteristics. According to the criteria we have studied, only risk of belonging to the MUHO phenotype was statistically significant in SGA-obese versus AGA-obese, so more studies are needed to understand and identify this risk difference and complementary studies will better characterise these two phenotypes for a better preventive approach.

Previous results from the Haguenau cohort have shown that being born SGA is a significant contributor to the risk of metabolic syndrome and SGA individuals had higher levels of IR.21 This higher probability of developing the metabolic syndrome for SGA-born individuals, could be related to both an increased weight gain (catch up process), and to fetal programming itself.27 The mechanisms underlying the favourable metabolic profile of MHO versus MUHO remain unclear. Epidemiological studies showed that obese individuals with no metabolic abnormalities and good level of fitness have a very good prognosis in long-term studies, even if MHO individuals sometimes showed a slightly higher risk of morbidities compared with healthy lean normal weight controls.9 26

The idea that some obese individuals develop cardiometabolic complications but not others has been proposed by Vague28 several years ago. Since then, researchers have tried understanding what was differentiating the so-called MHO in contrast with metabolically unhealthy participants. A potential pathophysiological hypothesis has been suggested in a recent study29 where MHO individuals had a decreased capacity of adipose tissue to transport glucose. Conversion of carbohydrate precursors was associated with adverse effects on metabolic health which would lead to decreased insulin sensitivity and metabolic syndrome.29 Adiposity, which is reduced at birth in SGA infants, undergoes a catch-up growth process during infancy and might lead to a disproportionately high fat mass in relation to muscle mass which is in turn involved with higher IR. McLaughlin et al30 found that MUHO individuals have higher levels of small adipose cells and decreased expression of differentiation markers, which could contribute in an unfavourable metabolic profile in MUHO individuals compared with MHO.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no published study comparing SGA-born and AGA-born individuals for metabolically healthy or unhealthy obesity. A study carried out on obese adolescents has shown that those who had high birth weight had higher adiponectin levels and increased insulin sensitivity compared with obese adolescents with low birth weight.31 Other data23 in the literature showed differences between SGA versus AGA for cardiovascular abnormalities later in life regardless of BMI but not on the MUHO phenotype in case of obesity and after 8 years of inclusion. However, since several studies have shown that SGA individuals display unfavourable metabolic profiles when compared with AGA ones;23 the same explanations underlying the favourable metabolic profile in MHO participants from the general population could be used in the obese ones. The percentage of MHO in this study is 26%, which is in the range of what is usually found in other studies using different methods to assess metabolically healthy obesity.26 We are not aware of any study comparing MUHO phenotype in obese individuals by birth weight for gestational age. We used the HOMA-IR index to determine the metabolically unhealthy phenotype. The HOMA-IR index has been shown to be an efficient measure of health status in the obese population.26

The main strengths of the present study include the homogeneous population studied and the high participation rate which reduces the risk of selection bias between SGA-born and AGA-born adults. Individuals grew up at a time where nutritional conditions were optimal and uniform in the area of Haguenau. Besides, participants have completed their pubertal development and are not at an advanced age to confound IR development and diabetes with ageing, making it a suitable population to answer our question. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the risk of MUHO with regard to birth weight for gestational age; and the first study to highlight the importance of studying different phenotypes of at-risk populations. We adjusted for age and sex in order to minimise confounding bias. Moreover, further adjustment for physical activity and socioeconomic status did not change the results.

Our study has however some limitations. We are using a small subgroup of the population and thus might have not had enough power to detect significant differences with regard to metabolic variables; still we were able to find a difference in the risk of MUHO in SGA versus AGA participants. Besides, we have used the HOMA-IR as a definition for the MHO phenotype, because of the lack of a standard definition for MHO, other ways of classifying MHO versus MUHO might lead to different interpretations. In summary, we have shown that young obese SGA-born individuals had a higher risk of belonging to the MUHO phenotype defined by the HOMA-IR index. Those findings are specific to this homogeneous population but can however be generalised to other young obese adults born SGA. The results from this study highlight the understanding of the importance of IR as a determinant for metabolically healthy obesity as well as the importance of preventing births that are SGA. In conclusion, SGA might confer a higher risk than AGA with regard to MUHO independently of age, sex, physical activity level and socioeconomic status. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings in different populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thanks to all the participants of the Haguenau cohort, and all the members of the Haguenau cohort study team. The present study was funded by ‘la Fondation Francophone pour la Recherche sur le Diabète’.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. SC contributed to interpretation of results and revised the manuscript. CC, CLM, JB, MP, MZ, EP-G and BC edited and reviewed the manuscript. JM is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Fondation Francophone pour la Recherche sur le Diabète.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Saint Louis Medical School at the Paris Diderot, University of Paris.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rahmouni K, Correia ML, Haynes WG et al. . Obesity-associated hypertension: new insights into mechanisms. Hypertension 2005;45:9–14. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000151325.83008.b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying A, Arima H, Czernichow S et al. . Effects of blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular risk according to baseline body-mass index: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2015;385:867–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61171-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czernichow S, Castetbon K, Salanave B et al. . Determinants of blood pressure treatment and control in obese people: evidence from the general population. J Hypertens 2012;30:2338–44. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283593010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckel RH, Kahn R, Robertson RM et al. . Preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a call to action from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2006;113:2943–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB et al. . Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med 2006;355:763–78. 10.1056/NEJMoa055643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world—a growing challenge. N Engl J Med 2007;356:213–15. 10.1056/NEJMp068177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karelis AD, Faraj M, Bastard JP et al. . The metabolically healthy but obese individual presents a favorable inflammation profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4145–50. 10.1210/jc.2005-0482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karelis A, Brochu M, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Can we identify metabolically healthy but obese individuals (MHO)? Diabetes Metab 2004;30:569–72. 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70156-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Milani RV. Healthy obese versus unhealthy lean: the obesity paradox. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015;11:55–62. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marini MA, Succurro E, Frontoni S et al. . Metabolically healthy but obese women have an intermediate cardiovascular risk profile between healthy nonobese women and obese insulin-resistant women. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2145–7. 10.2337/dc07-0419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messier V, Karelis AD, Prud'homme D et al. . Identifying metabolically healthy but obese individuals in sedentary postmenopausal women. Obesity 2010;18:911–17. 10.1038/oby.2009.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Primeau V, Coderre L, Karelis A et al. . Characterizing the profile of obese patients who are metabolically healthy. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:971–81. 10.1038/ijo.2010.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2482–8. 10.1210/jc.2011-3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calori G, Lattuada G, Piemonti L et al. . Prevalence, metabolic features, and prognosis of metabolically healthy obese Italian individuals the Cremona study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:210–15. 10.2337/dc10-0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Disparate effects of metabolically healthy obesity in coronary heart disease and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1079–81. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy-Marchal C, Jaquet D. Long-term metabolic consequences of being born small for gestational age. Pediatr Diabetes 2004;5:147–53. 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy-Marchal C, Czernichow P. Small for gestational age and the metabolic syndrome: which mechanism is suggested by epidemiological and clinical studies? Hormone Res 2005;65:123–30. 10.1159/000091517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of disease. Eur J Clin Invest 1995;25:457–63. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 2001;60:5–20. 10.1093/bmb/60.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Arriba A, Domínguez M, Labarta J et al. . Metabolic syndrome and endothelial dysfunction in a population born small for gestational age relationship to growth and Gh therapy. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2012;10:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaquet D, Deghmoun S, Chevenne D et al. . Dynamic change in adiposity from fetal to postnatal life is involved in the metabolic syndrome associated with reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 2005;48:849–55. 10.1007/s00125-005-1724-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papiernik E, Bouyer J, Dreyfus J et al. . Prevention of preterm births: a perinatal study in Haguenau, France. Pediatrics 1985;76:154–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meas T, Deghmoun S, Alberti C et al. . Independent effects of weight gain and fetal programming on metabolic complications in adults born small for gestational age. Diabetologia 2010;53:907–13. 10.1007/s00125-009-1650-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS et al. . Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2906–12. 10.1210/jc.2006-0594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinnouho G-M, Czernichow S, Dugravot A et al. . Metabolically healthy obesity and the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II cohort study. Eur Heart J 2015;36:551–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu123:ehu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinnouho GM, Czernichow S, Dugravot A et al. . Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of mortality does the definition of metabolic health matter? Diabetes Care 2013;36:2294–300. 10.2337/dc12-1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neel JV. Diabetes mellitus: a “thrifty” genotype rendered detrimental by “progress”? Am J Hum Genet 1962;14:353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. 1956. Obes Res 1996;4:204–12. 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabbrini E, Yoshino J, Yoshino M et al. . Metabolically normal obese people are protected from adverse effects following weight gain. J Clin Invest 2015;125:787–95. 10.1172/JCI78425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin T, Sherman A, Tsao P et al. . Enhanced proportion of small adipose cells in insulin-resistant vs insulin-sensitive obese individuals implicates impaired adipogenesis. Diabetologia 2007;50:1707–15. 10.1007/s00125-007-0708-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouhours-Nouet N, Dufresne S, de Casson FB et al. . High birth weight and early postnatal weight gain protect obese children and adolescents from truncal adiposity and insulin resistance metabolically healthy but obese subjects? Diabetes Care 2008;31:1031–6. 10.2337/dc07-1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011367supp.pdf (45.2KB, pdf)