Abstract

Objective

To determine whether an induction-maintenance strategy of combined therapy (methotrexate (MTX)+tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (TNFi)) followed by withdrawal of TNFi could yield better long-term results than a strategy with MTX monotherapy, since it is unclear if the benefits from an induction phase with combined therapy are sustained if TNFi is withdrawn.

Methods

We performed a meta-analysis of trials using the initial combination of MTX+TNFi in conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA). A systematic literature search was performed for induction-maintenance randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where initial combination therapy was compared with MTX monotherapy in patients with clinically active early RA. Our primary outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved low disease activity (LDA; Disease Activity Score (DAS)28<3.2) and/or remission (DAS28<2.6) at 12–76 weeks of follow-up. A random-effects model was used to pool the risk ratio (RR) for LDA and remission and heterogeneity was explored by subgroup analyses.

Results

We identified 6 published RCTs, 4 of them where MTX+adalimumab was given as initial therapy and where adalimumab was withdrawn in a subset of patients after LDA/remission had been achieved. 2 additional trials used MTX+infliximab as combination therapy. The pooled RRs for achieving LDA and clinical remission at follow-up after withdrawal of TNFi were 1.41 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.89) and 1.34 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.89), respectively. There was significant heterogeneity between trials due to different treatment strategies, which was a limitation to this study.

Conclusions

Initial therapy with MTX+TNFi is associated with a higher chance of retaining LDA and/or remission even after discontinuation of TNFi.

Keywords: Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, Anti-TNF, Treatment, Methotrexate, Disease Activity

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

A possible strategy in treating early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is to intensively initiate with combined tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) and methotrexate (MTX), followed by withdrawal of TNFi. However, studies investigating this principle have yielded somewhat conflicting results.

What does this study add?

This is the first meta-analysis showing that early intensive treatment of RA with MTX+TNFi followed by discontinuing the TNFi in an ‘induction-maintenance’ approach has clinical benefits for patients during the combined treatment as well as later when the TNFi is discontinued.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

If these results are confirmed, treating early RA with MTX+TNFi followed by maintenance with MTX alone may be a reasonable strategy despite high initial costs.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the therapeutic landscape for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has changed dramatically, especially due to the introduction of biological disease-modifying drugs (bDMARDs) such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi).1 2 There are currently five approved TNFi (adalimumab (ADA), etanercept, infliximab (IFX), golimumab and certolizumab pegol.3 Although they all target the same cytokine, there are differences in their molecular structure, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, which make them not identical. The main goal of RA treatment today is to achieve remission4 or at least low disease activity (LDA) when remission is not feasible. Treating to target is a strategy that aims to achieve a desirable disease state and change the treatment accordingly in order to reach the desired target. The rheumatologist as well as the patient should be involved in this process.5

Recommended by EULAR,6 the most commonly prescribed first-line conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) for RA therapy is methotrexate (MTX), as part of an initial strategy. However, in several randomised controlled trials (RCTs), combination therapy (MTX+TNFi) has been shown to yield improved response compared with MTX monotherapy7–11 and, if initiated very early, achieving and maintaining remission is more likely.12 It is still unclear whether discontinuation of TNFi is possible after LDA or remission is achieved. In order to answer this question, ‘induction-maintenance’ trials have been performed, where patients discontinue TNFi after a limited treatment period. Induction-maintenance trials use an intensive combination therapy (MTX+TNFi) early in the course of the disease as the first-line treatment (induction period) and then withdraw the biological agent (maintenance period).13 Some studies have suggested that the initial induction with intensive combination treatment may increase the possibility to sustain functional and quality of life benefits and maintain LDA after withdrawal of TNFi.14–16 We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to summarise the proportion of patients who achieve LDA and/or remission with combination therapy versus MTX monotherapy after a period of induction with TNFi and then withdrawal. The aim was to assess whether an induction-maintenance strategy of MTX+TNFi followed by discontinuation of TNFi could yield better long-term results than a strategy with MTX monotherapy.

Methods

This study was developed according to the Cochrane collaboration guidelines (http://www.cochrane.org) and followed a protocol that prespecified study selection, eligibility criteria, quality assessment, data abstraction and statistical analysis. The findings are reported according to the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)’.17

Search strategy

The search strategy was performed according to the ‘Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcome and Study design (PICOS)’ statement17 (table 1). In order to find RCTs, where the induction maintenance of combination therapy is tested, a systematic review of records was done using four databases from their inception until 9 May 2016; MEDLINE (Ovid, PubMed), EMBASE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL; which includes unpublished trials) and Clinicaltrials.gov. Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms included RA: rheumatoid arthritis, Methotrexate, antirheumatic agent, Adalimumab, Golimumab, Certolizumab pegol, Etanercept, Infliximab, tumor necrosis factor α, monoclonal antibody, biological product, limited to clinical trials in humans (see online supplementary table S1 for detailed search).

Table 1.

PICOS used to outline the research question

| Participants | Biologics and methotrexate-naïve adult patients with clinically active early rheumatoid arthritis with a disease duration ≤1 year or symptom duration ≤2 years |

| Intervention | Initial combination therapy (methotrexate+tumour necrosis factor inhibitor) and then discontinuation of the tumour necrosis factor inhibitor |

| Comparison | Methotrexate monotherapy |

| Outcome | Proportion of patients achieving low disease activity (DAS28<3.2) at follow-up after discontinuation of tumour necrosis factor inhibitor or achieving remission (DAS28<2.6) after discontinuation of tumour necrosis factor inhibitor |

| Study design | Randomised controlled trials |

DAS, Disease Activity Score.

rmdopen-2016-000323supp_tables.pdf (138.5KB, pdf)

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We selected studies (abstracts, published manuscripts and unpublished trials with results) that met the following criteria: (1) RCTs where initial combination therapy (MTX+TNFi) was compared with MTX monotherapy in adult patients with clinically active early RA, defined as disease duration <1 year or symptom duration <2 years; (2) discontinuation of the TNFi that had 3 months as the minimal initial duration of MTX plus TNFi; and (3) trials that reported disease activity at the end of the induction and maintenance periods. We required that the studies report information on our outcomes of interest. Our primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients achieving LDA (Disease Activity Score (DAS)28<3.2) or remission (DAS28<2.6) after the maintenance period. The secondary outcome was the proportion of patients achieving LDA or remission at induction. Studies were excluded if they were designed to evaluate patients with conditions other than early RA, had non-randomised study designs (ie, observational studies, non-comparative studies, case reports), non-English or were preclinical (animal) studies. Studies were excluded if the patients with RA were not on biologics and MTX naïve at the start of the trial and if the DAS was not reported.

Data extraction and study selection

The records were screened by title and abstract, first by one researcher (SE) and finally the potentially relevant RCTs were read thoroughly by two researchers (SE and EVA). Any differences were discussed until agreement was reached. Data on study year, type of TNFi, symptom/disease duration at baseline, age, per cent of female, DAS28 (C reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate), DAS/Health Assessment Questionnaire Disease Index (DAS/HAQ) at baseline, per cent of LDA/remission before discontinuation of TNFi (at induction), per cent of patients who reach remission at induction out of those who have already achieved LDA, required LDA before discontinuation (DAS-driven design), number of participants randomly assigned into the treatment arms, geographical region, number of weeks of induction therapy, number of weeks after discontinuation of TNFi, dosages of MTX/TNFi, additional therapy, blinding and per cent in LDA/remission after discontinuation were entered independently into standardised extraction forms. Quality assessment of the RCTs were evaluated with Jadad Quality Scale, which is a three-item, five-point quality scale to rate the quality of the trials; two points are given for descriptions of randomisation, two points for description of double-blinding and one point for description of withdrawal.18

Statistical analysis

Outcomes were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. For each trial, the risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI of the effects of combination therapy compared with MTX monotherapy were calculated. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to pool the data, allowing for within-study and between-study variation. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic and χ2 test where a p value <0.10 was considered to be statistically significant. A value of above 50% for I2 was considered to be high.19 The pooled RR represents an estimate of the increased chance of maintaining remission or LDA when using MTX+TNFi as initial therapy compared with MTX monotherapy. In addition, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the influence of individual studies. To examine potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted by stratifying on the basis of method of MTX administration (oral or subcutaneous), use of intra-articular glucocorticoid (GC) injections, type of blinding (blinded vs non-blinded), requirement of LDA at induction, induction period (12, 24–26 and 48–54 weeks) and type of TNFi. Statistical analyses were performed with ‘Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA)’ V.3. Publication bias was investigated using Begg's funnel plot and evaluated using Egger's regression test.20 21

Results

Literature search

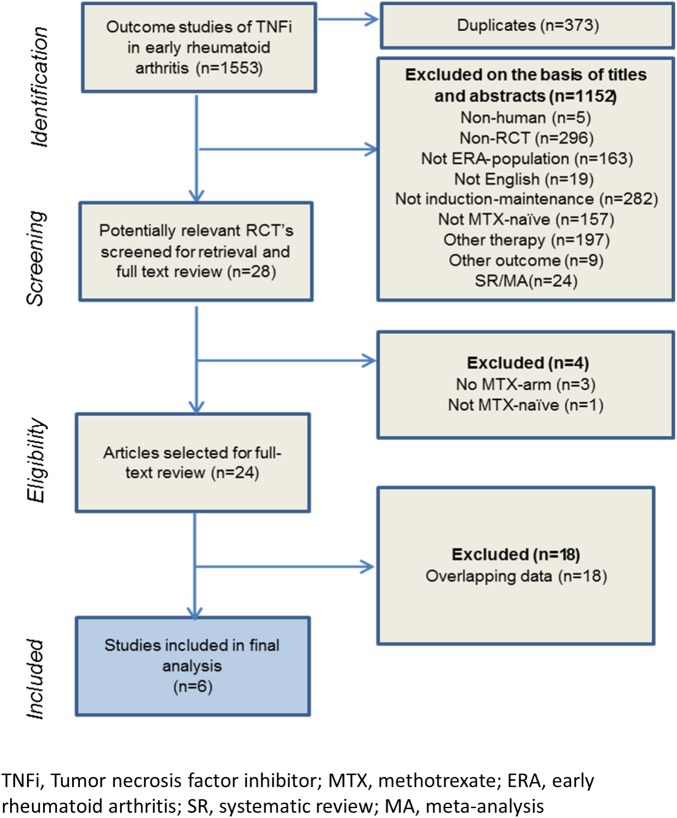

We identified 509 records in MEDLINE, 221 records in EMBASE, 780 records in CENTRAL and 43 records at clinicaltrials.gov (figure 1). Of the potentially relevant studies retrieved, the majority were excluded because they were not RCTs and/or they were not induction-maintenance trials. In one of the induction-maintenance trials, the patients were treated with MTX prior to the introduction of the TNFi, that is, the patients were not MTX naïve; therefore, the study was excluded.22 Another study was excluded because there was no MTX arm in the trial.23 In the end, a total of six studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (figure 1) where induction maintenance in early RA was tested using ADA24–27 and IFX.14 28 For two of the studies, we obtained the original data from the authors.26 27 The studies included involved 1723 csDMARD-naïve patients where 861 were randomised to MTX monotherapy and 862 were randomised to initial combination therapy followed by TNFi withdrawal.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection. ERA, early rheumatoid arthritis; MA, meta-analysis; MTX, methotrexate; RCT, randomised controlled trial; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; SR, systematic review.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are displayed in table 2. The trials included had been published between 2004 and 2014 and performed at 198 sites across the world. The LDA outcome was reported by all six included studies and the clinical remission outcome at maintenance was reported by all included studies except the BeST trial. All of the studies were investigator-initiated except for OPTIMA. Two out of five trials had a Jadad score of 3 because of the non-double blindness (see online supplementary table S2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study, year of publication | TNFi (dosage) | Dosage of MTX per trial arm, application route | Female (%), per trial arm | Age ±SD, years per trial arm | Blinding | Disease/symptom duration mean±SD, per trial arm at BL, months | Indicators of disease activity, per trial arm, mean ±SD | HAQ, mean±SD, per trial arm HAQ at BL±SD | Patients per trial arm | Added therapy (corticosteroids) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

T20 2004 |

Infliximab (3 mg/kg given at BL, 2 wks, 6 wks and at 8-wk intervals until 46 wks). | Both arms: 7.5 mg/wk at BL, 15 mg/wk at wk14 | Combo: 60 Mono: 60 |

Combo: 51±10 Mono: 53±14 |

54 wks double-blinded, then observational | Combo: 6(3–12)*/7±5† Mono: 5(3–11)*/6±4† |

DAS28-ESR by default Combo: 6 Mono: 7 |

Combo: 1±1 Mono: 1±1 |

Combo: 10 Mono:10 |

Glucocorticoids were not permitted for the first 14 wks of study. Thereafter (intra-articular or intramuscular) glucocorticoids were permitted if clinically required (maximum dose: 120 mg methylprednisolone in 3-month study periods). |

|

BeST 2005 |

Infliximab (3 mg/kg, adjusted after 3 months depending on DAS) Infliximab was increased from 3, 6, 7.5 to 10 mg/kg over 8 wks if persistent DAS over LDA) | Combo: 25–30 mg/wk Mono:15 mg/wk (was increased if LDA) |

Combo: 66 Mono: 68 |

Combo: 54±14 Mono: 54±13 |

Blinded joint assessors | Combo: median 0.5/6(3–12)* Mono: median 0.5/6(4–14)* |

DAS44-ESR by default Combo: 4±1 Mono: 5±1 |

Combo: 1±1 Mono: 1±1 |

Combo: 128 Mono:126 |

22% received intra-articular glucocorticoid injections in mono, while 13% received it in combo. |

|

GUEPARD 2009 |

Adalimumab (40 mg eow) | Both arms: maximum 20 mg/wk, orally | Combo:79 Mono: 81 |

Combo: 46 ±16 Mono: 49±15 |

Not blinded | Combo: ≤6/4(3–5)* Mono: ≤6/4(3–5)* |

DAS28-ESR by default Combo: 6±1 Mono: 6 ±1 |

Combo: 2±1 Mono: 1±1 |

Combo: 33 Mono: 32 |

A single intra-articular glucocorticoid injection was allowed during the trial. |

|

HIT HARD 2012 |

Adalimumab (40 mg eow) | Both arms: 15 mg/wk, sc | Combo: 70 Mono: 67 |

Combo: 47±12 Mono: 53±14 |

Double-blinded | Combo: 2±2/<4 Mono: 2±2/<4 |

DAS28-ESR by default Combo: 6(±1) Mono: 6(±1) |

Combo: 1±1 Mono: 1±1 |

Combo: 87 Mono: 85 |

Maximum ≤10 mg/day prednisone |

|

OPERA 2014 |

Adalimumab (40 mg eow) | Both arms: maximum 20 mg/wk, orally | Combo: 63 Mono: 69 |

Combo: 56 (26–78)* Mono: 54 (28–77)* |

Double-blinded during 12 months | Combo: <3/not stated Mono: <3/not stated |

DAS28-CRP Combo: 6(4–8)* Mono: 6(4–7)* |

Combo: 1 (0.2–3)* Mono: 1 (0.2–2)* |

Combo: 89 Mono: 91 |

Swollen joints injected with triamcinolone when required |

|

OPTIMA 2014 |

Adalimumab (40 mg eow) | Both arms: maximum 20 mg/wk, orally | Combo: 73 Mono: 67 |

Combo: 50±15 Mono: 49±13 |

Double-blinded | Combo: 4(3)/not stated Mono: 4(3)/not stated |

DAS28-CRP combo: 6±1 mono: 6±1 |

Combo: 2 (1) † Mono: 1 (1)† |

Combo: 515 Mono: 517 |

Co-therapy with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or prednisone or equivalent (≤10 mg/day), could continue at a stable dose for 4 wks or more before BL. |

*Median (IQR).

†Mean (SD).

BL, baseline; combo, combination arm; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS28, disease activity score by 28 joints; DAS44, disease activity score by 44 joints; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; LDA, low disease activity, eow, every other week; mono, MTX monotherapy arm; MTX, methotrexate; sc, subcutaneously; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; wk, week.

During maintenance, the LDA response after discontinuing the biologic in the MTX+TNFi group ranged from 33% to 83% and the remission rates ranged from 27% to 66%.

The largest trial included in the analysis, OPTIMA, tested the induction-maintenance strategy and showed that the patients in the trial maintained a stable LDA target on initial MTX+ADA even after withdrawal of ADA. The disease activity criterion for discontinuation of ADA was LDA, which had to be achieved at two visits spaced with 1 month. Following a year of maintenance treatment with MTX, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved remission who were started on combination therapy other than monotherapy (27% vs 15%; p<0.0001). In OPTIMA, more than 40% of patients were treated with systemic GCs at baseline.24

The two smaller studies (Guépard and HIT HARD26 27) also investigated the discontinuation of ADA. Both Guépard and the HIT HARD trial observed a higher proportion of patients achieving remission during maintenance (30% vs 22%; p=0.44) and (41% vs 33%; p=0.25), respectively, between those who had started with MTX+ADA versus those who started with MTX. Regarding LDA, the smaller Guépard trial revealed numerical but statistically non-significant differences in LDA response during maintenance (39% vs 22%; p=0.18), respectively, between those who had started with MTX+ADA versus those who started with MTX. In Guépard, the disease activity criterion for discontinuation of ADA was LDA. The same trend was observed in HIT HARD (51.7% vs 45.9%; p=0.44). In HIT HARD, ADA was discontinued regardless of disease activity.

The Opera trial showed no difference in achieving remission or LDA during maintenance between the two arms MTX+ADA (66% vs 69%; p=0.67) and MTX (83% vs 83%; p=0.94), respectively.29 After induction, LDA response in the MTX alone group was highest in Opera (76%) as well as the initial remission rates (49%). After induction, the initial remission rates in the MTX+TNFi group were also the highest in Opera (75%). This may have to do with the baseline DAS28 which was slightly lower in Opera, and moreover Opera used an aggressive intra-articular Triamcinolone treatment strategy which was added to MTX+ADA.30

Two trials were included that studied IFX. In Quinn et al,14 10 patients were randomised to receive MTX+IFX for a year followed by a maintenance treatment of MTX and standard clinical care, and another 10 patients received MTX monotherapy. During maintenance (50% vs 30%; p=0.36) and (70% vs 50%; p=0.36) achieved remission and LDA, respectively, between those who had started with MTX+ADA versus those who started with MTX. However, the study was very small. Additional therapies (sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine) were used in the MTX group and those patients also received more MTX than did the MTX+IFX arm in the second year of the study.

The BeST trial tested four different treatment strategies, of these we examined arm 4, induction maintenance with MTX+IFX, and compared with arm 1, MTX monotherapy. Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months depending on the DAS28; however, LDA had to be sustained for at least 6 months in order to withdraw IFX.31 More patients in arm 4 (56% at 2 years) could remain on MTX monotherapy with persistent LDA than patients who had initially started with MTX monotherapy (32% at t=2 years) with a significant difference (p<0.05).32

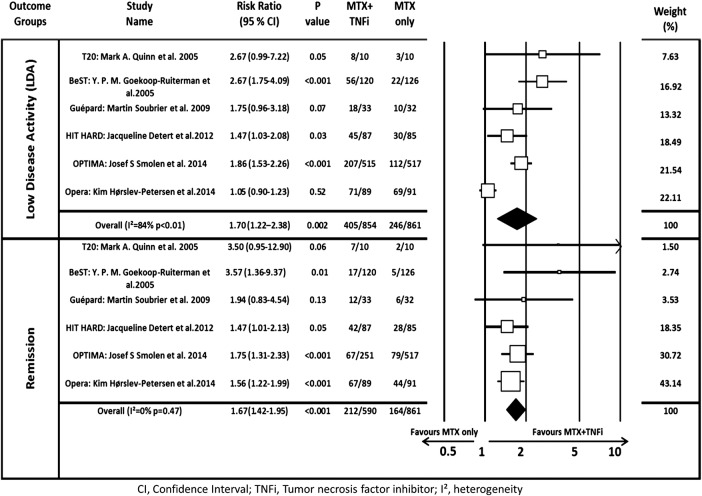

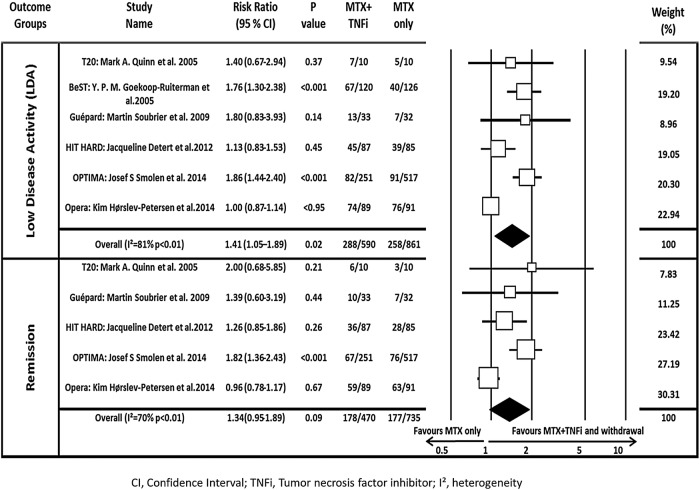

Data synthesis

At the end of the induction phase, the pooled RR for achieving LDA and remission was 1.70 (95% CI 1.21 to 2.38) and 1.67 (95% CI 1.42 to 1.95), respectively, confirming that combined therapy was significantly more effective than MTX monotherapy (figure 2). After discontinuing TNFi, the pooled RR for LDA and remission was 1.41 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.89) and 1.34 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.89), respectively, indicating that initial induction therapy was associated with better outcome even after discontinuing the biologic. Heterogeneity among these trials was high at 81% and 70% (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the risk ratio of attaining LDA or remission using combination therapy versus monotherapy at induction. The I² and p values for heterogeneity are shown (remission=DAS28<2.6; LDA=DAS28<3.2). DAS28, disease activity score by 28 joints; LDA, low disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the risk ratio of attaining LDA or remission using combination therapy versus monotherapy during maintenance. The I² and p values for heterogeneity are shown (remission=DAS28<2.6; LDA=DAS28<3.2). Note: for BeST, only LDA could be assessed. DAS28, disease activity score by 28 joints; LDA, low disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

The subgroup analysis showed that the Opera study appeared to change the heterogeneity dramatically (table 3). After exclusion of the Opera trial, due to the usage of GC as part of a treatment strategy, the pooled RR for LDA was 1.56 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.96; I2=41%, p=0.15) and the pooled RR for clinical remission was 1.59 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.99; I2=0%, p=0.48). The induction period of 12 weeks has the highest RR of 1.76 (95% CI 1.33 to 2.34; I2=0%, p=0.96), indicating that the induction period of 12 weeks is the most beneficial, compared with an induction period of 24–26 or 48–54 weeks. The sensitivity analyses examined the influence of each trial on the meta-analysis. Opera was the only study that had a large effect on the RR and heterogeneity. By excluding OPTIMA, BeST, Guépard and T20 one at a time, the RR and heterogeneity ranged from only 1.29 to 1.41 and 70% to 85%, respectively.

Table 3.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

| Variable | No of trials in the meta-analysis | RR (95% CI) LDA | I2 (p value) | No of trials in the meta-analysis | RR (95% CI) remission | I2 (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup analysis | ||||||

| Required LDA | 3 | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | 0% (0.54) | 3 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.44) | 32% (0.23) |

| Did not require LDA | 3 | 1.81 (1.50 to 2.19) | 96% (<0.001) | 2 | 1.76 (1.34 to 2.32) | 0% (0.55) |

| Induction period 12 weeks | 2 | 1.76 (1.33 to 2.34) | 0% (0.96) | 1 | NA | NA |

| Induction period 24–26 weeks | 2 | 1.46 (0.89 to 2.38) | 83% (0.02) | 2 | 1.55 (1.08 to 2.21) | 54% (0.14) |

| Induction period 48–54 weeks | 2 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.14) | 0% (0.37) | 2 | 1.14 (0.62 to 2.09) | 43% (0.19) |

| TNFi: adalimumab | 4 | 1.32 (0.93 to 1.90) | 84% (0.01) | 4 | 1.30 (0.90 to 1.87) | 76% (<0.01) |

| TNFi: infliximab | 2 | 1.70 (1.29 to 2.25) | 0% (0.58) | 1 | NA | NA |

| Double-blinded | 4 | 1.28 (0.91 to 1.82) | 83% (0.01) | 4 | 1.34 (0.91 to 1.98) | 78% (0.004) |

| No double-blinded | 2 | 1.76 (1.33 to 2.34) | 0% (0.96) | 1 | NA | NA |

| MTX subcutaneously | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA |

| MTX orally | 5 | 1.49 (1.03 to 2.16) | 85% (<0.001) | 4 | 1.39 (0.88 to 2.21) | 78% (0.004) |

| GC as part of a treatment strategy | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA |

| GC not part of a treatment strategy | 5 | 1.56 (1.25 to 1.96) | 41% (0.15) | 4 | 1.59 (1.28 to 1.99) | 0% (0.48) |

| Sensitivity analysis | ||||||

| Exclusion of OPTIMA | 5 | 1.29 (0.97 to 1.72) | 70% (0.009) | 4 | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.34) | 12% (0.33) |

| Exclusion of BeST | 5 | 1.33 (0.96 to 1.84) | 79% (<0.001) | NA | NA | NA |

| Exclusion of Guépard | 5 | 1.37 (1.00 to 1.88) | 84% (<0.001) | 4 | 1.34 (0.91 to 1.98) | 78% (0.004) |

| Exclusion of T20 | 5 | 1.41 (1.02 to 1.94) | 85% (<0.001) | 4 | 1.30 (0.90 to 1.87) | 76% (0.005) |

GC, glucocorticoids; I², heterogeneity; LDA, low disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; no, number; RR, risk ratio; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Egger's test was non-significant (p=0.20). A visual inspection of the funnel plot also showed no evidence of publication bias (see online supplementary table S3).

Discussion

Our study is the first to examine whether an advantage is seen even after withdrawal and during maintenance with MTX alone. Using a systematic literature review followed by a meta-analysis, we examined whether initial combination therapy is associated with a higher chance of retaining LDA and/or remission, even after discontinuation of TNFi. The pooled RR of LDA and remission after the maintenance phase showed that there is a 34–41% higher risk of achieving remission and LDA when using initial MTX+TNFi.

It has been shown earlier that combination therapy with a biological agent is superior to MTX monotherapy for remission in early RA. Whether remission can be maintained after withdrawal of TNFi therapy was systematically reviewed by Navarro-Millán et al,33 who concluded that discontinuation of TNFi(s) seemed possible when using an intensive initial treatment. In contrast to the current study, Navarro-Millán et al also included non-randomised trials and did not meta-analyse the results in terms of remission or LDA. Our study is more up to date, including the Guépard and Opera trials which were conducted in the past 5 years.

Strengths and limitations

The treatment effects in the six trials were inconsistent since the overall response rates at maintenance for the MTX-TNFi group varied from 33% to 83% and 27% to 66% for LDA and remission, respectively. The disease duration in the HIT HARD trial was very short with a mean of 1.6–1.8 months and the administration of MTX was performed subcutaneously as opposed to orally in the other trials. The two trials aforementioned and OPTIMA only allowed a maximum of one intra-articular injection of prednisolone, and fixed or oral prednisolone up to 10 mg daily. In the Opera trial, intra-articular GC use was consistent and mandatory throughout the study as part of the treat-to-target strategy where a total of 1710 injections were administered. The mean age within the patients in the Opera trial was to some extent higher, whereas the baseline DAS28 mean was slightly lower compared with the other trials.25 34 35

The studies included were not identical, and the details in the strategies differed; different induction and maintenance periods were used, in T20 additional therapies (csDMARDs) were used at maintenance in the MTX monotherapy arm, only two of the studies (HIT HARD and OPTIMA) were double-blinded throughout the trial, HIT HARD was the only one that administered MTX subcutaneously; Guépard, OPTIMA and BeST had a DAS-driven design and required LDA before the patients could discontinue the TNFi. The heterogeneity that is addressed here was explored by subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

The MTX dosage may introduce a source of bias in biological trials in RA.36 The suboptimal dose of 15 mg/week MTX in T20 and HIT HARD might have had an influence on the outcome of the results in this analysis. Additionally, the doses of MTX in the monotherapy arm in the BeST trial are slightly lower than in the combination arm.

Our data should be interpreted with caution. The small number of studies (n=6) qualifying for the inclusion criteria resulted in a lower power to detect sources of heterogeneity and to detect publication bias. We did not include non-English papers, which could have led to publication bias. However, we included abstracts and unpublished trials to minimise possible publication bias.

Generalisability of RCTs may be limited since patients are highly selected to participate in RCTs. The patients seen in routine practice are more diverse than those included in this study, who were csDMARD-naïve patients only with very high disease activity. Also, the maximum follow-up duration was 76 weeks, which makes it unclear whether the remission is sustained permanently.

Despite these limitations, the analyses are based on the best data available and all the studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria as described in the methods. The patients in the induction-maintenance trials are all patients with early RA, with a disease duration of <6 months. One of the factors that play a role in the treatment response is how established the disease has become,37 and since the overall goal is to be able to diagnose and treat patients at an as early stage as possible, our results indicate the possible treatment outcome for those who are in an early RA stage.38 The most consistent data regarding how these treatments work come from MTX-naïve patients in RCTs, since all patients are receiving active therapy for the first time and selection biases may play a less important role in determining outcomes. The literature search was comprehensive, and efforts were taken to obtain more data. Future studies should focus on an induction period of 12 weeks since the RR of the Guépard and BeST trials indicated that it might be the most beneficial induction treatment period. Additionally, in order to make the comparisons just, in the future it would be of interest to: compare the MTX+TNFi discontinuation arm with MTX (perhaps administered subcutaneously) combined with GCs, use similar optimised doses of MTX in both arms and to practise a treat-to-target strategy in the trial settings. Thus, the results must be interpreted with the comparator in mind.

Implications for practice

In today's clinical practice, there are several treatment strategies in RA. According to the EULAR recommendations, MTX should be part of the first-line treatment strategy and in case there is an intolerance, sulfasalazine or leflunomide should be considered. Also, as part of the initial treatment strategy, low-dose GCs should be considered (in combination with one or more csDMARDs) for up to 6 months. If the target is not reached, another csDMARD strategy should be considered. Furthermore, bDMARD should be considered if poor prognostic factors are present.39 Additionally, in future trials, it would be of interest to administer MTX subcutaneously rather than orally, since it is associated with greater clinical efficacy even at the same dose of 15 mg/week.40

According to our study, early intensive treatment of RA with MTX+TNFi has clinical benefits during the combined treatment as well as in an ‘induction-maintenance’ approach later when the TNFi is discontinued. This suggests that induction maintenance, despite high initial costs, may be a reasonable strategy for a subset of patients with early RA. However, to make this possible, conclusive biomarkers that can identify these patients are needed, which are not currently available. This approach may offer the potential that a more intensive and expensive treatment used for a restricted time provides a lasting benefit. Future RCTs confirming the ‘induction-maintenance’ approach may lead to a paradigm change in the treatment of early RA.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Elizabeth Arkema at @elizabetharkema

Contributors: RvV designed the study. SE and EVA performed the literature search. All authors interpreted the results, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests: Disclosures RvV. Research Support and Grants: AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Consultancy, honoraria: AbbVie, Biotest, BMS, Celgene, Crescendo, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Vertex. MD has participated at symposia and advisory boards organised by Abbvie, Pfizer, UCB, Merck, Sanofi, Novartis, Roche, BMS. GRB received grant/research support from Abbott.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monaco C, Nanchahal J, Taylor P et al. Anti-TNF therapy: past, present and future. Int Immunol 2015;27:55–62. 10.1093/intimm/dxu102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe F, Boers M, Felson D et al. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: physician and patient perspectives. J Rheumatol 2009;36:930–3. 10.3899/jrheum.080947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:3–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaujoux-Viala C, Nam J, Ramiro S et al. Efficacy of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, glucocorticoids and tofacitinib: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:510–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999;340:253–9. 10.1056/NEJM199901283400401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3432–43. 10.1002/art.20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keystone E, Heijde D, Mason D et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3319–29. 10.1002/art.23964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay J, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:964–75. 10.1002/art.23383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatzidionysiou K, van Vollenhoven RF. When to initiate and discontinue biologic treatments for rheumatoid arthritis? J Intern Med 2011;269:614–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Vollenhoven RF. New and future agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Discov Med 2010;9:319–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O'Connor PJ et al. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal: results from a twelve-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:27–35. 10.1002/art.20712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:918–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61811-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Kooij SM, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP et al. Patient-reported outcomes in a randomized trial comparing four different treatment strategies in recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:4–12. 10.1002/art.24367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L et al. Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:iii, ix–xi, 1–193 10.3310/hta14080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Smith GD. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ 1998;316:61–6. 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masao Nawata KS, Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Discontinuation of infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission. Mod Rheumatol 2008;18:460–4. 10.1007/s10165-008-0089-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1781–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1316133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R et al. Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: the randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet 2014;383:321–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61751-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Junker P et al. Adalimumab added to a treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intra-articular triamcinolone in early rheumatoid arthritis increased remission rates, function and quality of life. The OPERA Study: an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:654–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soubrier M, Puéchal X, Sibilia J et al. Evaluation of two strategies (initial methotrexate monotherapy vs its combination with adalimumab) in management of early active rheumatoid arthritis: data from the GUEPARD trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1429–34. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, an investigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:844–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Bijl AE, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK et al. Infliximab and methotrexate as induction therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2129–34. 10.1002/art.22718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Junker P et al. Very high remission rates are achieved by methotrexate and intraarticular glucocorticoids independent of induction therapy with adalimumab; year 2 clinical results of an investigator-initiated randomised, controlled clinical trial of early, rheumatoid arthritis (OPERA). Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:S1148–S. 10.1002/art.37847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Ørnbjerg LM et al. Clinical and radiographic outcome of a treat-to-target strategy using methotrexate and intra-articular glucocorticoids with or without adalimumab induction: a 2-year investigator-initiated, double-blinded, randomised, controlled trial (OPERA). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1645–53. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90. 10.1002/art.21405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allaart CF, Lems WF, Huizinga TW. The BeSt way of withdrawing biologic agents. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31(Suppl 78):S14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarro-Millan I, Sattui SE, Curtis JR. Systematic review of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor discontinuation studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2013;35:1850–61. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hørslev-Petersen K, Ørnbjerg LM, Hetland ML et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab on top of an aggressive treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intraarticular corticosteroid reduces radiographic erosive progression in early rheumatoid arthritis, even after withdrawal of adalimumab. Results of a 2-year trial (OPERA)(abstract). American College of Rheumatology; U.S.A: Meeting Abstracts (ACR) Annual Meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Peter J et al. Very high remission rates are achieved by methotrexate and intraarticular glucocorticoids independent of induction therapy with adalimumab; year 2 clinical results of an investigator-initiated randomised, controlled clinical trial of early, rheumatoid arthritis (OPERA)(abstract). American College of Rheumatology; U.S.A: Meeting Abstracts (ACR) Annual Meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durán J, Bockorny M, Dalal D et al. Methotrexate dosage as a source of bias in biological trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1595–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson JJ, Wells G, Verhoeven AC et al. Factors predicting response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of disease duration. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demoruelle MK, Deane K. Treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis and prevention of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:472–80. 10.1007/s11926-012-0275-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianchi G, Caporali R, Todoerti M et al. Methotrexate and rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence regarding subcutaneous versus oral routes of administration. Adv Ther 2016;33:369–78. 10.1007/s12325-016-0295-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2016-000323supp_tables.pdf (138.5KB, pdf)