Abstract

Objective

To recruit South Asian pregnant women, living in the UK, into a clinicoepidemiological study for the collection of lifestyle survey data and antenatal blood and to retain the women for the later collection of cord blood and meconium samples from their babies for biochemical analysis.

Design

A longitudinal study recruiting pregnant women of South Asian and Caucasian origin living in the UK.

Setting

Recruitment of the participants, collection of clinical samples and survey data took place at the 2 sites within a single UK Northern Hospital Trust.

Participants

Pregnant women of South Asian origin (study group, n=98) and of Caucasian origin (comparison group, n=38) living in Leeds, UK.

Results

Among the participants approached, 81% agreed to take part in the study while a ‘direct approach’ method was followed. The retention rate of the participants was a remarkable 93.4%. The main challenges in recruiting the ethnic minority participants were their cultural and religious conservativeness, language barrier, lack of interest and feeling of extra ‘stress’ in taking part in research. The chief investigator developed an innovative participant retention method, associated with the women's cultural and religious practices. The method proved useful in retaining the participants for about 5 months and in enabling successful collection of clinical samples from the same mother–baby pairs. The collection of clinical samples and lifestyle data exceeded the calculated sample size required to give the study sufficient power. The numbers of samples obtained were: maternal blood (n=171), cord blood (n=38), meconium (n=176), lifestyle questionnaire data (n=136) and postnatal records (n=136).

Conclusions

Recruitment and retention of participants, according to the calculated sample size, ensured sufficient power and success for a clinicoepidemiological study. Results suggest that development of trust and confidence between the participant and the researcher is the key to the success of a clinical and epidemiological study involving ethnic minorities.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY; PUBLIC HEALTH; South Asian, recruitment, retention, ante-natal blood, meconium, clinico-epidemiology.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Recruitment and retention of vulnerable groups of pregnant women and newborn babies from an ethnic minority, which have been historically difficult to recruit into clinical research.

Collection of multiple clinical samples: antenatal blood, cord blood and meconium samples from the same mother–baby pairs.

Information was volunteered by parents who declined to participate and/or to donate their baby's meconium samples.

As required by the Ethics Committee, collection of blood samples was only permitted during the routine drawing of blood by the midwives or phlebotomists; as a consequence, it was delayed or became unavailable in some instances.

Introduction

Background

The under-representation of South Asians and other ethnic minority groups in clinical trials affects the generalisability of findings leading to inequalities in access to healthcare.1 Recruiting participants, especially from ethnic minority groups, is a major challenge for the success of clinical research,2 the recruitment process being described as the ‘largest single workload component’2 and a ‘difficult process’.3

Recruiting ethnic minority participants into clinical or epidemiological research requires ‘cultural sensitivity’, and ‘cultural competence’, which includes translation of this sensitivity into the design and conduct of the research.4 5 The barriers to recruitment of ethnic minority participants into clinicoepidemiological research are widely recognised to be multifactorial, but remain poorly understood. Pragmatic constraints such as language or literacy and associated transcription costs are obvious barriers. Unfounded stereotypes sustaining cultural myths held by researchers are less obvious, but are a challenge to culturally competent research.

The perception of potential participants, informed by their identities, beliefs, values and traditions, is critical, but discrepancies between these and the cultural values of researchers may undermine attempts to recruit and retain participants. Adapting research design and implementation strategies to minimise cultural difference is likely to be important, even though cultural factors can be diverse or specific for a particular ethnic group. Research participants are not a single entity; they are heterogeneous; therefore, culturally tailored recruitment methods can improve recruitment.

Conservativeness of South Asian women has been described as a cultural attribute.1 6 The practice of conservativeness begins from within the family, where women usually experience a submissive position within ‘patriarchal family structures’.1 A South Asian woman's wishes and desires are expected to be commensurate with those of her family's tradition, honour and interest. The woman's husband and mother-in-law play a vital role in decision-making.

The non-participation of South Asian women in clinical research might depend on conservativeness. However, the impression of conservativeness and submission are Western cultural constructs. Successful recruitment of ethnic minority participants has been noted to be influenced by perceptions of trust and confidence in the research team6 and access to South Asian women reported to be more successful through mediation of known third parties, via gender-specific organisations such as childcare groups and sometimes via male family members.7

South Asian communities, that is, Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani and Sri Lankan, commonly speak their own languages, and may have limited skills in speaking or reading English. This problem can be overcome by including an interpreter in the research team, although this increases the cost of research.8 9 The fact remains, however, that excluding ethnic minorities from clinical studies can introduce substantial bias.9–13

Given this backdrop, the primary aim of this study was to collect data on participants' lifestyle by questionnaire survey and to collect maternal blood, cord blood and meconium for biochemical analysis in a clinicoepidemiological study in the UK (Leeds) named MaBEL: Mother's and Baby's Exposure to Lead (S Neelotpol. Evaluation of lead in meconium: a study on UK infants of South Asian origin. Unpublished PhD thesis, School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, UK. 2013). Collection of biomatrices requires pragmatic consideration for specimen acquisition, storage and analytical technique. Recruitment and retention are important factors determining successful sample acquisition. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to record and explore the influential factors and to devise an effective method of participant recruitment, retention and sample acquisition in an ethnic minority group—pregnant South Asian UK resident women, compared with pregnant Caucasian women. The purpose of including the comparison group was to establish the expected range of values of biomarkers present within the wider population group (S Neelotpol, unpublished PhD thesis, 2013).

Methods

Sample size

Given the fact that limited information exists on lead exposure among South Asian women and children in the UK, a sample size for this study was calculated as 75 for the study group of South Asian pregnant women and 30 for the comparison group of Caucasian pregnant women.14 Separate sample sizes were calculated to be 30 for each of the subgroups for comparison (second antenatal blood, cord blood and second meconium sample passed).14

Description of participants

The eligibility criterion of the participants (pregnant women in Leeds) was that their ancestral origin should be South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan) for the study group and Britain or Europe for the comparison group.

Setting

The study took place at the North of England UK National Health Service (NHS) Hospital Trust between February and June 2011. Recruitment of the participants and the collection of antenatal blood took place in the antenatal clinic and delivery suite. Postnatal wards were used for the collection of cord blood and meconium samples, respectively.

Assessment of challenges and development of methods to overcome

The challenges that could arise during recruitment and retention of study participants up to delivery and their identification during delivery were assessed in two ways: (1) by summarising the findings of previous studies from reviewing the literature; (2) pretesting the questionnaire and the study design with nine initial participants (five South Asian and four Caucasian participants) before the actual recruiting started. Accordingly, some methods were developed in this study in order to overcome those challenges of recruitment and retention of ethnic minority participants for the collection of different biomatrices.

At the beginning, with the permission of the hospital midwife, the chief investigator (CI) identified and communicated with South Asian women at the recruitment site. For both the study group and the comparison group, a brief description about the study was provided at the beginning of the recruitment process in order to highlight the significance of the study and to maintain transparency in the collection of data. Having a South Asian background with reasonable proficiency in major languages of the region, the CI used Bengali, Sylheti, Hindi and Urdu languages to explain the study to most of the South Asian participants.

In order to publicise the participant recruitment process, three methods were employed: (1) displaying the approved ‘MaBEL’ poster on the notice board of specific units within the hospitals which included various antenatal clinics and the prenatal ward within the NHS Trust; (2) distributing leaflets among the potential participants in antenatal classes, antenatal clinics and prenatal ward at the hospitals, as well as in some shops where South Asian customers visit regularly to shop (post codes: LS6, 7, 8 and 11); and (3) undertaking a direct approach to potential participants at the hospital during routine blood testing time, close to the 12th and 26th weeks of gestation.

In the present study, in order to retain the participants from recruitment until the birth of their baby, the CI sought to develop a good relationship with them by several means. These included sending them personalised text messages with good wishes, especially on various religious occasions such as during Ramadan and Eid (to Muslims); Diwali and Durga Puja (to Hindus); and Easter (to Christians).

For the collection of biomatrices, once written consent was obtained from the participants, the CI gave them a request slip for the midwife/phlebotomist to collect a 2 mL blood sample, exclusively for this study only during routine blood sampling(as per the advice of the Ethics Committee). However, it was observed that participants might forget or neglect to give the request slip to the midwife/phlebotomist in most cases. To overcome this problem, a bright pink sticker (marking ‘MaBEL’) was placed on the first page of the maternity file of the participant.

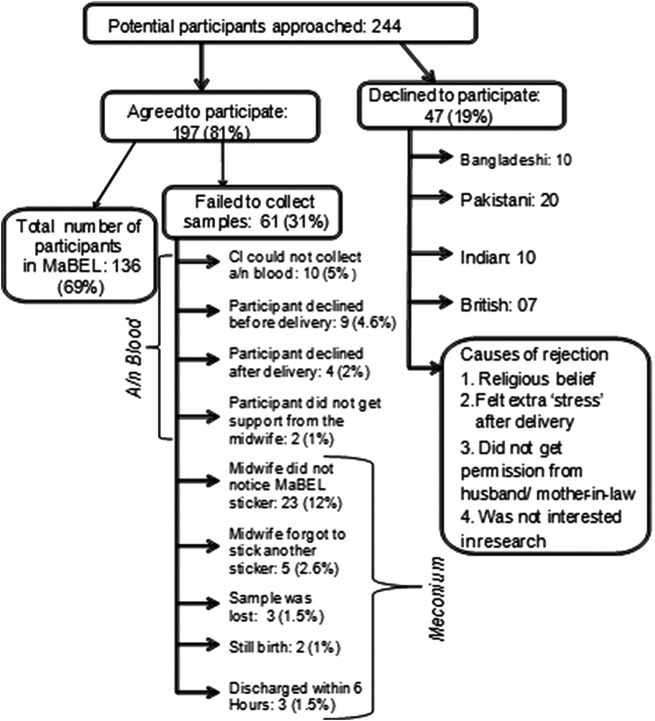

The flow charts below (figure 1) illustrate the method followed for the recruitment of potential participants into the study, how the lifestyle questionnaire survey was performed and the method employed for the collection of biological samples.

Figure 1.

Process of participant recruitment and collection of biological samples. CI, chief investigator.

Collection of the filled-in lifestyle questionnaire

Once recruitment of the participants was confirmed with informed consent, the questionnaire was handed over. All participants completed the questionnaire at a time most convenient to them, either at recruitment or at home. According to the researchers, response rates in surveys are usually considerably lower among ethnic minorities than among the native population.15 For this reason, the CI of the study was very careful about the collection of the completed questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

To analyse quantitative data from this study, simple statistical measures such as the mean, median, SD, percentage and IQR were used and the results were collated in tabular and graphical format. Data analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS, V.19.

Results

The majority of the participants (98%) were recruited from the antenatal clinics of the study site. The average age of the participants was 31 years (range 20–48). The ethnic background of the study group was of Bangladeshi (11%), Indian (28%) and Pakistani origin (61%). In the comparison group, four participants (10.5%) were born outside of the UK, elsewhere in the European Community. In the study group, based on the origin of birth, 37 participants (37.8%) were (by birth) British South Asian; the remaining 61 participants (62.2%) had migrated to and lived in the UK for a median period of 7 years (IQR 8); the median age at which these women had migrated to Britain was 22 years (IQR 7). A direct approach to potential participants while attending antenatal clinics gave the best recruitment outcome among the three methods (table 1).

Table 1.

Methods of participant recruitment and outcome

| Methods | Response | Difficulty incurred |

|---|---|---|

| Method 1: MaBEL posters placed in specified areas of hospitals and GP surgeries | No response | NA |

| Method 2: leaflets distributed in hospitals after antenatal classes | Received no response from the South Asians and little response from Caucasian participants | The majority of women were identified late in gestation (>36 weeks) when routine blood sampling is not performed. Thus, these women become ineligible for inclusion. |

| Method 3: Direct approaches to potential participants in antenatal clinics | Very good response. Fewer than 19% of those approached declined to take part (see later). | Gave consent but participants sometimes forgot or neglected to give a request slip to their midwife/phlebotomist to collect blood for MaBEL. |

GP, general practitioner; MaBEL, Mother's and Baby's Exposure to Lead; NA, not available

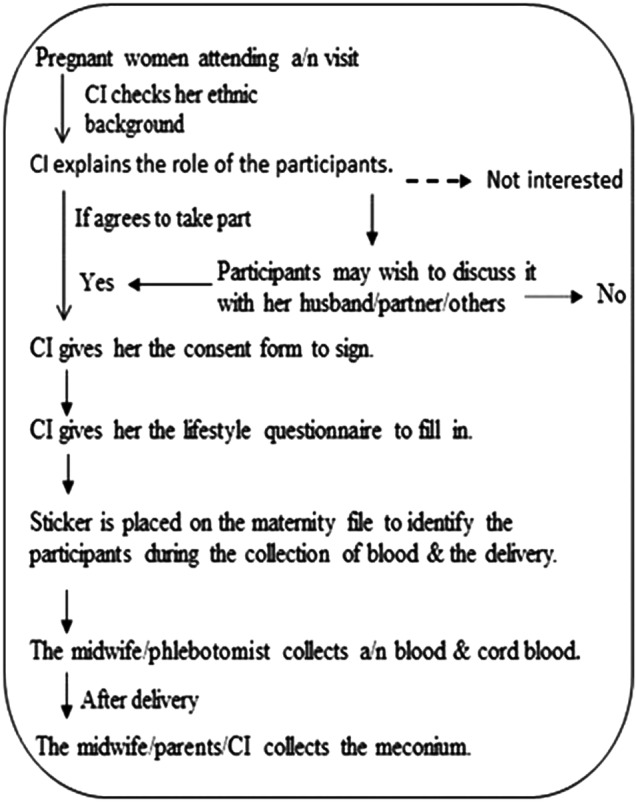

The target rate for recruitment was 5–8 participants per week. In practice, a recruitment rate of 14 participants per week, on average, was achieved by option 3. Figure 2 represents a graphical presentation of the recruitment of participants into the MaBEL study within 14 weeks.

Figure 2.

Rate of participant recruitment for the MaBEL study. MaBEL, Mother's and Baby's Exposure to Lead.

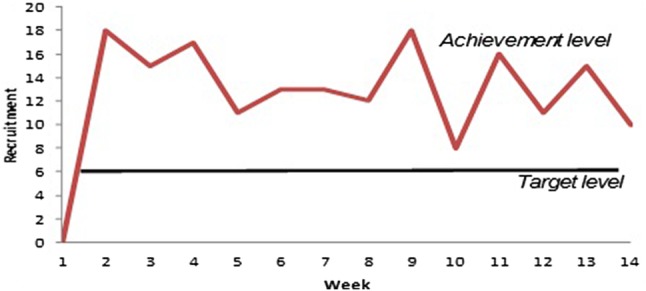

Initially, 244 pregnant women were approached by the CI, of whom 197 (81%) consented to participate and 47 (19%) declined. The potential participants were under no obligation to specify a reason for their non-participation in the study. However, they voluntarily stated some reasons for declining to participate. These were:

Religious beliefs (n=4 South Asian);

Felt ‘stress’ during pregnancy (n=13);

Husband or mother-in-law did not give permission (n=15 South Asian);

Were not interested in the research (n=15 Caucasian participants).

The number of potential participants approached and finally recruited into the study is summarised in figure 3, which also includes the reasons for the failure of the collection of antenatal blood and meconium samples.

Figure 3.

Final recruitment of participants in the MaBEL study. CI, chief investigator; MaBEL, Mother's and Baby's Exposure to Lead.

In total, 136 participants were included in the MaBEL study, of whom 98 were of South Asian origin and 38 of white Caucasian background. For these participants, complete responses to the lifestyle questionnaires (n=136), maternal blood samples (n=171; ie, 136 in the second trimester and 35 in the third trimester), cord blood samples (n=38) and meconium samples (n=176; first meconium: 136, second meconium: 40) were collected, more than the minimum calculated sample size required.

Optimal method for the collection of meconium

While the majority of antenatal blood samples (n=172) were collected by the CI, a protocol was developed for the collection of meconium samples that included midwives in the delivery suite, midwives and nursery nurses in the postnatal ward, parents and the CI. Collection of meconium by ward midwives proved difficult because of the demands of their clinical load which often conflicted with the collection of research samples. For the parents also, it was a time when they were preoccupied with the needs of their new baby and the collection of research samples was not high on their list of priorities. Moreover, (though not always), there are cultural barriers that may prevent South Asian fathers from participating in the changing of nappies and hence the collection of meconium from their newborn babies.

This study intended to evaluate factors affecting the successful collection of meconium in order to identify the method most likely to provide samples optimal for analysis. The optimal method of collection was determined from assessment of the following variables:

Number of meconium samples collected successfully by the hospital midwife, the researcher and the parents;

Compliance with sample collection;

Sequential sampling;

Adequacy and quality of sample.

For different meconium collection methods, a comparison of person against time, weight and number of meconium samples is presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of meconium collection methods

| Person involved | Number of meconium samples collected | Number of sequential samples | Mean time elapsed from collection to storage of samples in minutes (SD) | Mean weight of meconium in grams (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwife | 21 (15.4%) | 11 | 23.76 (32.8) | 1.83 (2.38) |

| Researcher | 30 (22.1%) | 0 | 14.5 (7.5) | 2.94 (3.16) |

| Parents | 85 (62.5%) | 29 | 25.71 (31.6) | 1.93 (2.1) |

From the findings presented in table 2, it was therefore clear that parents collected most of the samples of meconium (63%); midwives assisted with this process on 15% of occasions, while the remainder was collected by the CI (22%). Table 3 presents an assessment of the level of motivation of participants with this project.

Table 3.

Assessment by the CI about the extent of participants' motivation to assist with sample collection

| Number of participants (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Level of motivation of participants to assist with sample collection | Study group (n=98) | Comparison group (n=38) |

| Excellent* | 21 (21) | 8 (21) |

| Good/very good | 64 (65) | 24 (63) |

| Average | 11 (11) | 6 (16) |

| Not good | 2 (2) | 0 |

Good/very good: informed the CI before the antenatal blood sampling and/or collected and preserved the meconium sample(s) spontaneously or with the help of a midwife.

Average: supported the midwives in sample collection but they did not do anything proactively.

Not good: midwife provided a container for the collection of meconium, but participants failed to collect it. The CI collected a second meconium sample later.

*Excellent: informed the CI (by sending text messages) before or after the collection of all biomatrices.

CI, chief investigator.

Discussion

The recruitment process for ethnic minorities is the largest single workload component in a research project according to several studies.17 18 In a study conducted in the UK, Pakistani-Kashmiri interviewers described the recruitment of South Asian participants into research as a difficult process because of the conservative nature of their culture.3 For example, to recruit and retain the South Asian participants in the study, it is important to recognise the influential people in their lives, such as husbands and mother-in-laws. This is also an indication of the reality and cultural practices, in that all of the South Asian women who participated were married. There were some instances where the women withdrew their consent, sending an SMS message, after a few weeks because either the husband or the mother-in-law refused to allow them to take part in the study. This cultural orientation among South Asians has also been identified in other studies.1 7

As another instance of conservative cultural practice, this study showed that among the total meconium samples collected (table 2), 85 (62.5%) samples were collected by the parents, among which 55 (65%) were collected by South Asian parents. However, among the South Asian parents, only 3% of fathers of the newborn babies had changed the nappy and collected the meconium sample. It was only the available female members of the family such as the participant, her mother or mother-in-law, sister or sister-in-law, or aunt who collected the sample(s). Under such circumstances where both parents were not playing similar roles, the participants needed to be confident that they could request their female family members or available female relatives to help collect the samples in time.

Moreover, scientists have raised concerns about language barriers with people from ethnic minorities and perceived cultural stereotypes and that these factors may result in them being systematically excluded from trials or research.9–12 Being the largest ethnic minority in the UK, however, there should be adequate representation of the South Asian population in research; excluding them from clinical research may engender considerable bias.9 10 18 Moreover, the process of recruitment may be even harder since there is often a need to retain the participants for a longer period of time.

Challenges overcome during the recruitment of the potential participants

In order to recruit people from ethnic minority groups into clinical research, this study used three methods or approaches. The best outcome was observed from the ‘direct approach’ method where all queries or anxieties of the participants could be answered by the CI. This method was supported by posters displayed in the recruitment area. However, since the leaflet was developed in English, this might be one of the reasons why hardly any South Asian participants showed interest in the study.

Various reasons for refusing to take part in the study were voluntarily stated by some participants. These included:

Religious beliefs or superstitions; the potential participants did not want to donate anything (even meconium) at the beginning of their baby's life;

The potential participants did not want to take on any extra responsibility or ‘stress’ after delivery of their child;

Husband or mother-in-law did not give permission;

The potential participants were not interested in the research project.

To overcome these challenges, the CI used different approaches that necessitated building the trust of potential participants.6 19 20 As a Bangladeshi woman herself, the CI was sensitive to culturally specific factors and to religious practices; accordingly, she was conscientious in her approach to study group participants when seeking to engage them in the research process. Her sensitivity to cultural norms and practices was extremely important for securing the confidence of participants. To be specific, when approaching South Asian women with a view to recruiting them, the CI introduced herself according to their religious/cultural practices, for example, starting with ‘Salaam’ (to Muslims) or ‘Namaste’ (to Hindus) (meaning ‘Hello’ in English), with an intention to engage with them on a personal level. Having a reasonably good command over Bengali, Sylheti, Hindi and Urdu, there were little or no language barriers for the CI to communicate with potential participants. These were the probable reasons for which the CI had been able to recruit 98 South Asian and 38 Caucasian pregnant women, where the target minimum was to recruit 75 South Asian and 30 Caucasian pregnant women. The reason for recruiting more participants above the target level was that the acquisition of calculated clinical samples from mother–baby pairs would be achieved even if the CI failed to collect the required samples from some recruited participants.

Challenges overcome for collection of clinical samples

After recruiting the participants with written informed consent, the CI gave them a request slip to give to the midwife or phlebotomist for the collection of an antenatal blood sample. However, at the beginning of the study, some participants did not give it to them. Since the CI could not collect a blood sample from them in those instances, they had to be excluded from the study.

In clinical and epidemiological research, the number of participants and clinical samples collected is very important to provide the study with sufficient power. Keeping this in mind, the whole process of recruitment and retention was meticulously followed. Yet the identification of study participants for collection of different clinical samples became challenging and cumbersome, since they move between hospitals and the community. For example, sometimes the midwife, owing to their heavy workload, failed to identify the participants for collection of antenatal blood or for the collection of meconium samples after delivery. As a result, failure of the collection to a considerable extent of antenatal blood (n=10, ie, 5%) and meconium samples (n=23, ie, 12%) occurred. To overcome this challenge, a ‘MaBEL’ sticker was therefore placed by the CI inside the maternity file during recruitment. This helped the midwife to remain aware of the collection of antenatal blood from the participants.

Once the woman in the delivery suite was identified as a study participant, the midwife put another ‘MaBEL’ sticker inside the baby's ‘birth record file’ for the collection of cord blood and meconium samples. In practice, this meant signposting study participants which was done by ‘tagging’ (or monitoring) their medical notes as they moved from the community midwifery services, to the labour ward, to the postnatal ward and back to the community midwives. Therefore, the purpose of using this sticker inside the maternity file was only to facilitate the identification of the participants by the healthcare staff at different stages of collection of biomatrices. Since this sticker marked as ‘MaBEL’ was only tagged inside the file and contained only the ‘serial number’ of the participants, the anonymity of the participants was assured. Moreover, the serial number helped to match the same mother–baby pairs in the collection and analysis of lifestyle questionnaire data, antenatal blood, cord blood and meconium samples. As a result, the stickers readily gave a visual effect and a reminder, and played a vital role in the identification of recruited participants in the later collection of different biomatrices.

Challenges overcome in retention of participants

Participant retention was another vital goal for this study, which took place over a relatively long time frame (approximately 3–5 months for each participant). To retain the recruited South Asian participants, their husband and/or mother-in-law played an influential role. In sharp contrast, most Caucasian participants made their decision to participate themselves and were observed to remain more committed in their participation and contribution to the study. As compared with their South Asian counterparts, their opinions to participate in research were not influenced by their partner/husband or mother-in-law. Personal contacts by the CI, through sending text messages on a mobile phone, with greetings during festivals were established in the belief that the participants would build a rapport with the researcher and that this would encourage the participants to play a more active role in the research process.16

Other challenges overcome

During the recruitment process, the first challenge was to make the participants aware of the importance of the study for their children. After recruitment, identification of the participants at different stages for the collection of biosamples was another major challenging step for this moderately spanned project (February to July 2011). For example, although meconium is a waste product, its collection is very difficult for the hospital midwives with busy schedules and for the parents exhausted after delivery of their babies. An even more challenging step was to inform and raise the awareness of each and every hospital midwife based in the prenatal wards and delivery suites. The main reasons for this were that hospital midwives worked on a rota basis and delivery of a baby could happen at any time within a 24-hour period. It proved difficult to ensure that every midwife successfully identified each participant who came under their care and labelled the baby's ‘birth record file’ with a MaBEL sticker to signal the intended collection of further samples. To overcome this problem, the Head of Midwifery in the Trust and the ward managers for the delivery suite and the prenatal wards of two hospitals were asked to highlight the study to all relevant midwives (achieved by placing reminders for the collection of samples in their ‘Communication book’). Awareness was also raised by producing MaBEL participant stickers which were attached inside the medical notes (eg, bright pink ‘MaBEL: Cord blood; MaBEL: Meconium’), as they moved from the community to the labour ward, to the postnatal ward and back into the community. This proved a considerable challenge, but the direct communication by SMS text messaging from the participants to the CI substantially limited failures in sample collection.

Implications for practice

The success rates for recruitment and retention of participants in the MaBEL study indicated that certain practices adopted by the CI helped to a great extent an increase in the engagement of participants from ethnic minority groups, including:

A ‘direct approach’ and a one-to-one engagement with participants by the researcher to secure their informed consent, as well as to resolve any queries or anxieties they might have about research of this nature. Personal approaches were supported by posters displayed in the recruitment area.

It was highly beneficial for participants to be approached by someone from the same ethnic background who could understand their language and also be aware and appreciative of their culture. That is why researcher's sensitivity to cultural norms and practices was extremely important for securing the confidence of participants.

Participant retention was aided by creating a social relationship and maintaining contact by mobile text messaging, to determine when the mother was admitted to hospital for childbirth.

To identify the participants and to standardise the collection of meconium samples, one option might have been to provide participants with preweighed nappies for their newborn baby, ‘branded’ with a MaBEL label. Moreover, placement of a meconium collection pot in the maternity file during recruitment might have been another option to identify the participants during delivery.

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that the recruitment and participation of people of South Asian origin in clinical research in developed countries is often low because of language barriers, cultural differences and the higher costs incurred in their recruitment.7 Since South Asians are the largest ethnic minority in the UK (Census, 2001), there should be adequate representation of their participation in research. The strength of this study lies in its contribution to empirical and methodological issues on how to improve recruitment of ethnic minorities in clinical research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to the participants for their participation in the research at such crucial periods of their lives.

Footnotes

Contributors: SN, AWMH, AJJ and MWW contributed in designing the study and in obtaining ethical permission. SN recruited the participants, conducted the interviews, analysed the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. MWW supervised SN's recruitment process and the analysis of data. All authors contributed to the writing up of the final manuscript.

Funding: This research has been conducted for the partial fulfilment of the PhD study of the chief investigator (SN). She was awarded an Overseas Research Students Award Scholarship (ORSAS) by the University of Leeds and a Tetley & Lupton UK fund bursary. The School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, and Charles Wallace Bangladeshi Trust provided funding for the recruitment of the participants and the laboratory costs.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and granted ethical approval by the Yorkshire and Humber Research Ethics Committee (Leeds East REC: 10/H1306/32), the Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust (Ref: CSP No. NP/0067) and LTHT R&D No: UI10/9507.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rana BK, Kagan C, Lewis S et al. British South Asian women managers and professionals: experiences of work and family. Women Manag Rev 1998;13:221–32. 10.1108/09649429810232173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitken L, Gallagher R, Madronio C. Principles of recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Int J Nurs Pract 2003;9:338–46. 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean CA, Campbell CM. Locating research informants in a multi-ethnic community: ethnic identities, social networks and recruitment methods. Ethn Health 2003;8:41–61. 10.1080/13557850303558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvard Catalyst. Cultural competence in research. Annotated bibliography. HarvardMedical School, Diversity Inclusion & Community Partnership, 2010. https://catalyst.harvard.edu/pdf/diversity/CCR-annotated-bibliography-10-12-10ver2-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean CA, Campbell CM. Locating research informants in a multi-ethnic community: ethnic identities, social networks and recruitment methods. Ethn Health 2003;8:41–61. 10.1080/13557850303558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeilly M, Musick M, Efland JR et al. Minority populations and psychophysiological research: challenges in trust building and recruitment. Harvard Catalyst Profiles. J Ment Health Aging 2000;6:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brah A. Race and culture in the gendering of labour markets: South Asian young women and the labour market. New Community 1993;19:441–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacNeill V, Nwokoro C, Griffiths C et al. Recruiting ethnic minority participants to a clinical trial: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002750 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. South Asian participation in clinical trials: the views of lay people and health professionals. Health Policy 2006;77:149–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twamley K, Puthussery S, Macfarlane A. Recruiting UK-born ethnic minority women for qualitative health research—lessons learned from a study of maternity care. Res Policy Plann 2009;27:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooney LK, Bhopal R, Halani L et al. Promoting recruitment of minority ethnic groups into research: qualitative study exploring the views of South Asian people with asthma. J Public Health 2011;33:604–15. 10.1093/pubmed/fdq100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stirland L, Halani L, Raj B et al. Recruitment of South Asians into asthma research: qualitative study of UK and US researchers. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:282–90. 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown BA, Long HL, Gould H et al. A conceptual model for the recruitment of diverse women into research studies. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2009;6:625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johanson GA, Brooks GP. Initial scale development: sample size for pilot studies. Educ Psychol Meas 2010;70:394–400. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waheed W, Hughes-Morley A, Woodham A et al. Overcoming barriers to recruiting ethnic minorities to mental health research: a typology of recruitment strategies. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:101 10.1186/s12888-015-0484-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polin RA, Fox WW. Fetal and neonatal physiology. USA: WB Sunders Company, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feskens R, Hox J, Lensvelt-Mulders G. Collecting data among ethnic minorities in an international perspective. Field Methods 2006;18:284–304. 10.1177/1525822X06288756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason S, Hussain-Gambles M, Leese B et al. Representation of South Asian people in randomised clinical trials: analysis of trials’ data. BMJ 2003;326:1244–5. 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel MX, Doku V, Tennakoon L. Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2003;9:229–38. 10.1192/apt.9.3.229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levkoff SE, Levy BR, Weitzman PF. The matching model of recruitment. J Ment Health Aging 2000;6:29–38. [Google Scholar]