Abstract

Background

Children under the age of 12 months may receive an early dose of measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine to provide short-term protection in the case of a disease outbreak. Following a measles outbreak in Alberta, Canada, there was concern that children who received an early dose may not be returning for their routinely scheduled dose at 12 months, leaving them vulnerable to disease in the long term.

Methods

This population-based study of children born between 2006 and 2014 used administrative health data to assess coverage and timeliness of the first routine dose of MMR vaccine administered at age 12–24 months for children who received an early dose of the vaccine due to a disease outbreak. We compared this group to children who received an early dose due to travel to a measles-endemic region and to children who did not receive an early dose.

Results

Only 5.5% of 366 351 children received an early dose. Coverage for the routine dose at age 24 months was 96.5% for children receiving an outbreak dose, 92.2% for those travelling to measles-endemic regions and 86.6% for those without an early dose (p<0.0001). The multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, controlling for neighbourhood income, place of residence and interaction effects, determined that, as compared to the general cohort, the outbreak group was most likely to obtain the first routine dose (adjusted HR (aHR): 1.52, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.60), followed by the travel group (aHR: 1.26, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.34).

Conclusions

It is reassuring that the majority of children who received an early dose returned for their routine dose and did so in a timely manner.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of a centralised immunisation repository enabled us to assess vaccine uptake for the entire population of age-appropriate children.

The presence of unique personal health numbers allowed us to deterministically link immunisation data with other population-wide administrative databases to determine coverage levels and to control for covariates.

The limitation of administrative data is that it does not allow us to examine parents' reasons for or against seeking immunisation.

Introduction

Given the recent outbreaks of measles worldwide,1–4 it is important to ensure that children are receiving effective protection from disease through timely immunisation. In Canada, it is recommended that children receive two doses of measles-containing vaccine after the age of 12 months, with the first routine dose scheduled for 12 months of age.5 However, in case of a disease outbreak or travel to a measles-endemic region, it is recommended that an ‘early dose’ be administered to children aged 6–11 months, in order to afford them short-term protection.6 7 This early dose does not provide long-term protection, so timely reimmunisation at 12 months of age is critical.6 7

In the fall of 2013, there was an outbreak of measles disease in southern Alberta, a province of 4.1 million people in western Canada. The outbreak lasted from 18 October 2013 until 6 January 2014 and resulted in 43 cases of disease. A second separate measles outbreak occurred in Calgary and Edmonton (the two largest cities in Alberta) and central Alberta a few months later, lasting from 29 April until 4 July 2014 and resulted in 31 cases. During these outbreaks, early doses of measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine were offered to children 6–11 months residing in these regions.

At the conclusion of the outbreaks, there was concern among clinicians and policy advisors that parents might not be fully aware of the need for their child to return for their child's 12-month routine dose, and may mistakenly believe that the early dose their child received was adequate protection. Given that there were no previous studies to inform decision-making on this issue, we sought to assess and compare coverage and timeliness for the regularly scheduled 12 month dose (referred to as the ‘routine dose’) for: (A) children who received an early dose due to an outbreak, (B) children who received an early dose due to travel to a measles-endemic region and (C) children in the general Alberta population who did not receive an early dose.

Methods

Setting

Alberta has a universally available healthcare system, publicly funded through the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan (AHCIP), which is available to all Albertans. Each Alberta resident receives a personal health number to access health services, which can be used to link individual health records and other administrative databases. Routine childhood immunisations are administered free-of-charge by public health nurses in community-based clinics on a schedule determined by the Alberta Ministry of Health.8

Study design and data sources

This retrospective population-based study assessed coverage and timeliness of the first routine dose of measles-containing vaccine administered between 12 and 24 months using immunisation, vital statistics and AHCIP databases. The provincial immunisation repository, known as ImmARI, records childhood immunisations administered since 2006. ImmARI includes data on immunisation date, vaccine name, postal code of residence, reason for immunisation and birth date. The Vital Statistics Registry includes data on births and deaths for all children born in Alberta. AHCIP provides data on Alberta residents, including dates and reasons for insurance cancellation. All three data sets were deterministically linked by the personal health number.

The study included two mutually exclusive cohorts: the early dose and the general cohorts. The early dose cohort was selected from ImmARI; they were children receiving MMR at 6–11 months in Alberta from 1 January 2007 to 4 July 2014 (birth date: January 2006–January 2014). The reason for immunisation documented in ImmARI (travel or outbreak) was used to separate this cohort into two groups. The general cohort was chosen from the Vital Statistics Registry; they were children born in Alberta between January 2006 and January 2014 who did not receive an MMR early dose by the study end date of 31 May 2015. Children who left the province or died before 12 months were removed from both cohorts, as were First Nations children living on reserve and children living in the town of Lloydminster, whose immunisations are not delivered by the Alberta public health system. Using postal code of residence, both cohorts were linked with the publicly available Canada Census database9 to capture neighbourhood income quintiles (Q1: lowest, Q5: highest) and urban/rural place of residence. The general cohort was linked with ImmARI to obtain MMR immunisation data. A categorical variable was created to indicate if the child was from the general cohort or from the outbreak or travel groups in the early dose cohort.

Statistical analysis

Survival analysis was used to create a Kaplan-Meier curve of the timeliness of the first routine dose. Time to event was calculated from the 1-year birthday to the earliest of the immunisation date or the censoring date, with censoring for death, health insurance plan cancellation or end of follow-up period (31 May 2015 or age 24 months, whichever was earlier). The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the timeliness in the outbreak and travel groups and the general cohort. Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to estimate the effect of cohort on first routine immunisation, controlling for neighbourhood income quintile and rural/urban place of residence. Crude HR, adjusted HR (aHR) and corresponding 95% CIs were computed. All possible interactions were investigated. Data management and statistical analyses were performed by SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

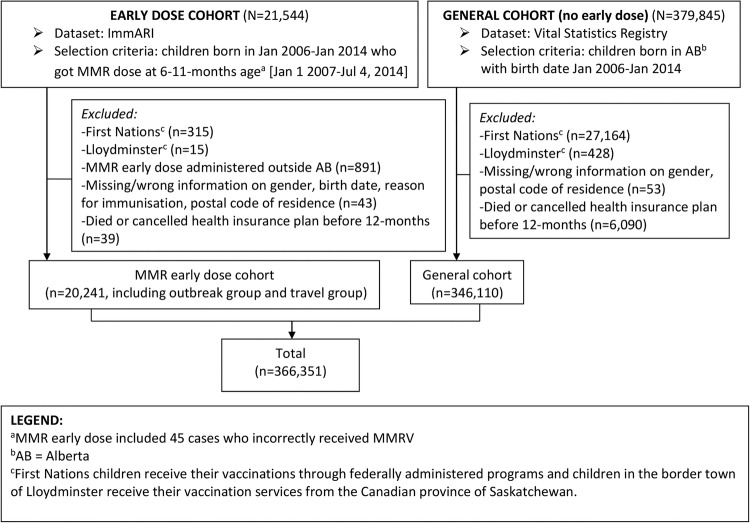

After exclusions (figure 1), a total of 366 351 children born between January 2006 and January 2014 were included in this study. Of these, 346 110 (94.5%) were children in the general cohort and 20 241 (5.5%) in the early dose cohort.

Figure 1.

Cohort selection flow chart, Alberta, 2007–2014. ImmARI, immunisation repository; MMR, measles–mumps–rubella; MMRV, MMR-Varicella.

In the early dose cohort, 59.1% (n=11 963) of the MMR vaccine administered to children aged 6–11 months was due to outbreaks and 40.9% (n=8278) due to travel. All of the outbreak doses were administered as a result of the two measles outbreaks in Alberta in the fall of 2013 and spring of 2014.

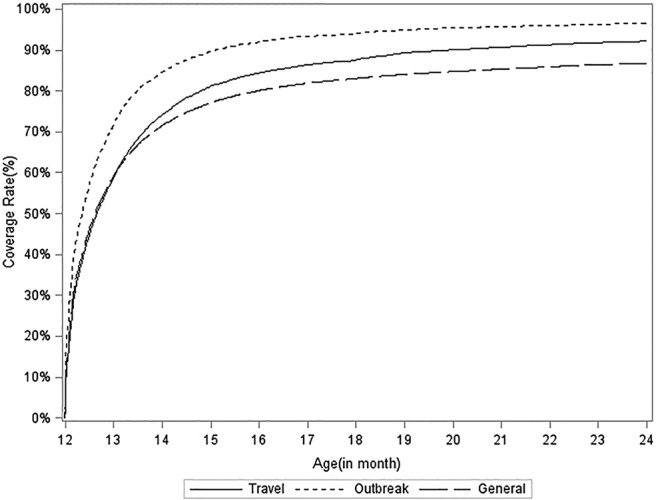

As displayed in table 1 and figure 2, the outbreak group received subsequent immunisations significantly earlier than the travel group, which was, in turn, earlier than the general cohort (p<0.0001). This pattern was consistent through every time point (except at ≤13 months when the general cohort was marginally higher than the travel group). Coverage at age 24 months for the outbreak group (96.5%) and the travel group (92.2%) was notably higher than for the general cohort (86.8%).

Table 1.

Coverage for the first routine measles–mumps–rubella dose at ages 12–24 months, Alberta, 2007–2014

| Age (starting at 12 months) | General cohort (%) | Early cohort |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel group (%) | Outbreak group (%) | |||

| ≤13 months | Overall* | 58.3 | 57.9 | 70.8 |

| Income† | ||||

| Q1 | 54.1 | 50.9 | 66.9 | |

| Q2 | 56.6 | 54.0 | 68.8 | |

| Q3 | 57.8 | 57.3 | 70.0 | |

| Q4 | 59.9 | 59.7 | 73.0 | |

| Q5 | 62.5 | 63.8 | 73.3 | |

| Place of residence‡ | ||||

| Urban | 59.5 | 57.1 | 71.5 | |

| Rural | 53.9 | 63.5 | 66.1 | |

| ≤15 months | Overall* | 76.9 | 80.9 | 89.6 |

| Income† | ||||

| Q1 | 72.8 | 74.2 | 86.3 | |

| Q2 | 75.6 | 78.8 | 88.0 | |

| Q3 | 76.5 | 79.7 | 88.9 | |

| Q4 | 78.4 | 83.5 | 90.7 | |

| Q5 | 80.6 | 85.3 | 92.1 | |

| Place of residence‡ | ||||

| Urban | 78.0 | 80.6 | 89.9 | |

| Rural | 72.6 | 82.8 | 87.3 | |

| ≤18 months | Overall* | 83.0 | 87.5 | 94.0 |

| Income† | ||||

| Q1 | 79.5 | 82.4 | 92.0 | |

| Q2 | 82.0 | 86.4 | 93.0 | |

| Q3 | 82.7 | 86.1 | 93.7 | |

| Q4 | 84.3 | 90.2 | 95.2 | |

| Q5 | 86.0 | 90.3 | 95.1 | |

| Place of residence‡ | ||||

| Urban | 84.0 | 87.6 | 94.1 | |

| Rural | 79.2 | 86.8 | 93.6 | |

| ≤24 months | Overall* | 86.8 | 92.2 | 96.5 |

| Income† | ||||

| Q1 | 83.9 | 88.3 | 95.4 | |

| Q2 | 85.8 | 91.6 | 95.4 | |

| Q3 | 86.4 | 91.4 | 96.6 | |

| Q4 | 88.0 | 94.5 | 97.1 | |

| Q5 | 89.4 | 94.0 | 97.0 | |

| Place of residence‡ | ||||

| Urban | 87.7 | 92.4 | 96.4 | |

| Rural | 83.5 | 90.7 | 96.5 | |

*Statistically significant difference in overall coverage between the three groups at p<0.0001.

†Statistically significant difference between each level of income for each group at p<0.0001.

‡Statistically significant difference between rural and urban place of residence for each group at p<0.0001.

Figure 2.

Timeliness of routine measles–mumps–rubella dose, Alberta, 2007–2014. Statistically significant difference in overall coverage between the three groups (p<0.0001).

Higher coverage was associated with higher income at all time points (table 1, p<0.0001). For the outbreak group, 97.0% of children in the Q5 income level received the first routine dose by 24 months, compared to 95.4% for Q1. The same pattern can be seen in the travel group and general cohort.

In the general cohort, children living in urban areas consistently had greater uptake of the routine dose than those living in rural areas (p<0.0001). In the outbreak group, for children ≤18 months, coverage for the routine dose was higher for children living in urban areas than those in rural areas (p<0.0001); however, by 24 months the coverage was almost the same. In the travel group, coverage for children ≤15 months in urban areas fell behind; however, at 24 months, coverage in urban areas was 92.4% compared to 90.7% in rural areas (p<0.0001).

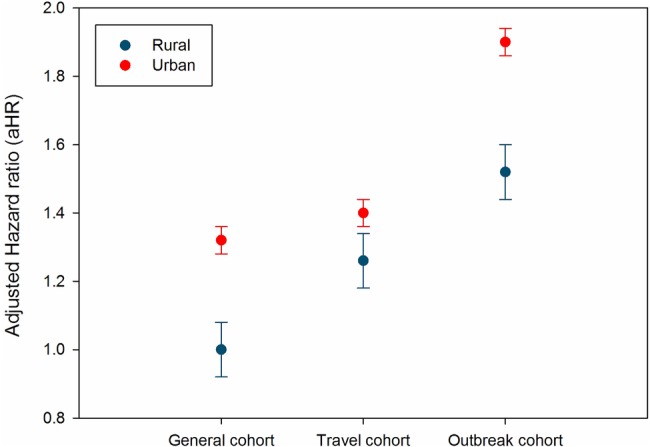

The multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, which controlled for neighbourhood income, place of residence and interaction effects, determined that, as compared to the general cohort, the outbreak group was most likely to obtain the first routine dose (aHR: 1.52, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.60), followed by the travel group (aHR: 1.26, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.34).

There was an interaction effect between place of residence and income quintile and between the place of residence and the groups. After controlling for the interaction between the two covariates (place of residence and income quintile), coverage in all groups remained higher in children living in an urban area, but the effect was reduced in the travel group (figure 3). As compared to children in the general cohort in a rural area, the aHR for receiving the routine vaccine dose before age 24 months in a rural area was 1.26 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.34) for children in the travel group and 1.52 (95% CI 1.44 to 1.60) for children in the outbreak group. For children in an urban area, the aHR for receiving the routine vaccine dose before the age of 24 months (as compared to children in the general cohort in a rural area) was 1.32 (95% CI 1.30 to 1.35) for children in the general cohort, 1.40 (95% CI 1.36 to 1.44) for children in the travel group and 1.90 (95% CI 1.85 to 1.95) for children in the outbreak group.

Figure 3.

Adjusted HR (aHR) for association between group and receipt of first routine dose by 24 months, by place of residence, Alberta, 2007–2014. Controlling for income quintile and interaction between income and location of residence (reference category: general cohort, rural residence).

Discussion

The two measles outbreaks that occurred in Alberta in 2013 and 2014 accounted for more than half (59.1%) of the early doses of MMR being administered in Alberta between 2007 and 2014. Children who received an early dose due to the outbreaks were more likely to return for their routine 12-month dose in a timely manner than children who received an early dose due to travel to a measles-endemic region. Both these groups were timelier than children in the general cohort who did not have an early dose. This was a consistent trend at all the time points from 12 through 24 months. Higher income was associated with higher coverage for all three groups at all the time points. The association between groups and places of residence (urban vs rural) was less straightforward, as the place of residence had a statistical interaction with income and group; coverage was generally higher for urban residents in the outbreak group and general cohort, but less so for the travel group.

Only one previous study10 has assessed uptake of the routine MMR dose following receipt of an early dose during a disease outbreak. As part of a larger study of vaccine effectiveness following a 1986–1987 measles outbreak in Florida, Hutchins et al10 found that ≥80% of children who had received an early dose (before 12 months) were reimmunised by 2 years. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the timeliness of the routine dose following an early dose, nor examined the differential timeliness of uptake depending on the reason for the early dose.

Our interest in examining the timeliness of vaccine uptake following an early outbreak dose arose from a concern that parents might not be aware of the need for the 12-month routine dose. We had expected that parents who were prompted to get an early dose for their child due to a disease outbreak may interpret this early dose as conferring adequate protection, and may not return for the routine dose (at all, or in a timely manner). However, our hypothesis was incorrect. Parents who were prompted to immunise their child early due to the outbreak returned for the routine dose in a timelier manner than parents in the general cohort, and as compared to parents who had sought out an early dose due to travel to a measles-endemic region. Unfortunately, administrative data is not able to elucidate the reasons for parents' decisions. We can only presume that one or more of the following are the cause: (1) the public health nurses that administered the early dose provided adequate education regarding the importance of returning for the early dose; (2) parents who sought out immunisation for their child during an outbreak were more proactive and/or committed to immunisation, which increased the likelihood of them returning for the routine dose in a timely manner; and/or (3) parents' perception of the increased risk of disease due to a local outbreak motivated them to ensure their child received the recommended routine dose. Certainly, studies have shown that parents' perception of disease risk is a critical driver of the decision to immunise their child.11–13 However, there is mixed evidence as to whether vaccine uptake actually increases following a disease outbreak.14 15

It is noteworthy that in September 2010, Alberta switched from using the MMR vaccine for the 12-month immunisation to MMR-Varicella (MMRV), with a recommendation to use MMR vaccine for an early dose. Although it is possible that introduction of MMRV may have influenced timeliness of vaccine uptake for the first routine dose, provincial surveillance data show unchanged coverage for measles-containing vaccine in the years following MMRV introduction.16

The influence of income quintile and place of residence on timeliness of uptake of the routine dose is important to consider, as it can guide decisions about populations needing additional follow-up. Vaccine coverage was higher in higher income quintiles, suggesting that lower income neighbourhoods may need additional prompts or supports to return for the routine MMR dose. This finding is consistent with studies of uptake of other vaccine doses, in which uptake is lower in low income families, often due to structural barriers to uptake.17–19 Even after controlling for income and the interaction between income and place of residence, and between group and place of residence, uptake was higher in urban regions. Evidently, additional efforts are needed to ensure rural residing children return for their routine dose.

Conclusion

Although it is recommended to administer early doses of MMR vaccine to children during a measles outbreak or for travel to a measles-endemic region, this is the first study to assess the timeliness of uptake of the routine measles-containing dose following receipt of an early dose. It is encouraging to see that the vast majority of children who received an early dose due to a measles outbreak returned for their routine dose, and did so in a timely manner. The uptake in this group exceeds that of the travel group and general cohort and suggests that public health practices to inform parents of the importance of a routine dose after an outbreak dose were successful. This type of assessment is important to assess whether existing public health mechanisms are adequate to prompt timely immunisation following an outbreak situation or whether additional strategies should be enacted. It may be worthwhile to assess coverage for the second routine dose, scheduled for age 4–6 years, once enough time has elapsed to permit follow-up of the outbreak group.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Larry Svenson for his support for this work and Douglas Dover for his analytic advice.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Shannon MacDonald at @SE_MacDonald

Contributors: The contributions of the authors are as follows: SEM conceived and designed the study, guided data analysis, drafted the article and approved the final version. XG contributed to the conception and design of the study, conducted the data analysis, provided substantial input on drafting the manuscript and approved the final version. KS and JS contributed to the conception and design of the study, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: SEM was supported by a Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a postdoctoral Clinician Fellowship from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles Cases and Outbreaks. CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Updated 10 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowcroft NS. The challenges of sustaining measles elimination in Canada. CCDR 2014;40:261–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance data. ECDC. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/measles/epidemiological_data/pages/annual_epidemiological_reports.aspx Updated 3 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antona D, Lévy-Bruhl D, Baudon C et al. Measles elimination efforts and 2008–2011 outbreak, France. Emerging Infect Dis 2013;19:357–64. 10.3201/eid1903.121360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Heath Agency of Canada (PHAC). Canadian Immunization Guide: Timing of vaccine administration. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/p01-09-eng.php Updated 18 February 2016.

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Canadian Immunization Guide: Part 1-Key immunization information. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/p01-eng.php Updated 23 April 2014.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles, Mumps, and Rubella vaccine use and strategies for elimination of measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome and control of mumps: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 1998;47 RR-8):1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberta Health. Routine immunization schedule. Alberta Health. http://www.health.alberta.ca/health-info/imm-routine-schedule.html Updated 1 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Canada. Census of population program datasets. Statistics Canada; http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/datasets/index-eng.cfm?Temporal=2011 Updated 13 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchins SS, Dezayas A, Le Blond K et al. Evaluation of an early two-dose measles vaccination schedule. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1064–71. 10.1093/aje/154.11.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmon DA, Moulton LH, Omer SB et al. Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:470–6. 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015;14:99–117. 10.1586/14760584.2015.964212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald SE, Schopflocher DP, Vaudry W. Parental concern about vaccine safety in Canadian children partially immunized at age 2: a multivariable model including system level factors. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:2603–11. 10.4161/21645515.2014.970075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf ER, Opel D, DeHart MP et al. Impact of a pertussis epidemic on infant vaccination in Washington State. Pediatrics 2014;134:456–64. 10.1542/peds.2013-3637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberta Health. Vaccine uptake following a measles outbreak in Alberta. 2015. http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/HTA-2015-04-14-Measles-Vaccine-Outbreak.pdf Posted 14 April 2015.

- 16.Alberta Health. Immunization: Childhood coverage rates. Interactive Health Data Application . Updated April 2016. http://www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/selectSubCategoryParameters.do

- 17.Szilagyi PG, Schaffer S, Shone L et al. Reducing geographic, racial, and ethnic disparities in childhood immunization rates by using reminder/recall interventions in urban primary care practices. Pediatrics 2002;110:e58 10.1542/peds.110.5.e58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttmann A, Manuel D, Dick PT et al. Volume matters: Physician practice characteristics and immunization coverage among young children insured through a universal health plan. Pediatrics 2006;117:595–602. 7 10.1542/peds.2004-2784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmel SR, Burns IT, Wolfe RM et al. Addressing immunization barriers, benefits, and risks. J Fam Pract 2007;56:S61–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]