Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe prepregnancy smoking, pre-natal smoking, and prenatal cessation among women reporting and not reporting depression or anxiety.

METHODS

We analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2009–2011 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a population-based survey of women with live births (N=34,633). Smoking status was defined as self-reported prepregnancy smoking (during the 3 months before pregnancy), prenatal smoking (during the last 3 months of pregnancy), and prenatal cessation (no smoking by the last 3 months among prepregnancy smokers). Depression and anxiety status was self-reported of having either condition or both during the 3 months before pregnancy. We compared smoking prevalence by self-reported depression and anxiety status using χ2 tests and adjusted prevalence ratios.

RESULTS

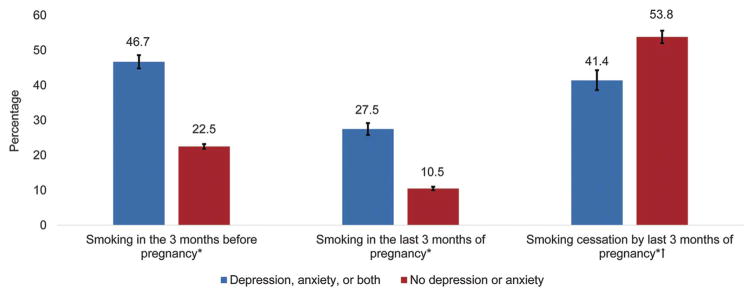

Overall, 16.9% of women in our sample reported depression, anxiety, or both during the 3 months before pregnancy. Compared with those who did not report, women who reported depression or anxiety had significantly higher prepregnancy (46.7% compared with 22.5%, P<.01) and prenatal smoking (27.5% compared with 10.5%, P<.01). A lower proportion of prepregnancy smokers who reported depression or anxiety quit smoking by the last 3 months of pregnancy than those who did not report (41.4% compared with 53.8%, P<.01). In adjusted analyses, women reporting depression or anxiety were 1.5 and 1.7 times more likely to smoke prepregnancy and prenatally, respectively, and less likely to quit smoking (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.80–0.92).

CONCLUSION

Women who reported depression, anxiety, or both were more likely to smoke before and during pregnancy and less likely to quit smoking during the prenatal period. Screening recommendations for perinatal depression and anxiety provide an opportunity to identify a subpopulation of women who may have a higher prevalence of smoking and to provide effective tobacco cessation interventions and mental health care.

Approximately 1 of 10 (11.6%) pregnant women smoke in the last 3 months of pregnancy,1,2 which is far from the Healthy People 2020 objective of decreasing smoking to 1.4%.3 Subgroups with high smoking prevalence include young women, those with lower socioeconomic status, substance users, and those with comorbid mental health disorders.4–6 Clinical recommendations have included routine tobacco use screening at every prenatal care visit,7 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that clinicians screen all pregnant women for depression and anxiety symptoms.8

Few population-based studies exist examining the associations between smoking and mental health status around the time of pregnancy. A few studies have reported a significant association between postpartum depression and anxiety and postpartum smoking and relapse.9–11 An analysis of a 2001–2002 national sample of women who became pregnant in the past year found independent associations between nicotine dependence and major depression, dysthymia, and panic disorder.5 However, it is unclear how depression and anxiety are associated with smoking before and during pregnancy. The extent to which pregnant women reporting depression or anxiety smoke can inform tobacco cessation efforts.

We examined prepregnancy smoking, prenatal smoking, and smoking cessation by depression and anxiety status and whether smoking differed by health insurance coverage. Health coverage for smoking cessation and depression treatments may now be covered in Medicaid and insurance plans.12–15 Finally, we assessed whether reported depression and anxiety status is independently associated with smoking before and during pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2009–2011 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, which is a state- and population-based surveillance system among women who deliver liveborn neonates in the United States. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System collects data on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System methodology has been described elsewhere.16 Briefly, at each site, a monthly stratified sample of 100–300 new mothers is selected systematically from birth certificates, and these women are contacted by mail. Attempts are made to interview women by phone after nonresponse to repeated mailings. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System survey is completed at 2–6 months after delivery. Data are weighted to represent all women who delivered live births in each site. Of the 40 states and New York City that participated in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System during the study period, our study included nine states (Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming) that queried women about depression and anxiety during the 3 months before pregnancy and achieved an overall weighted response rate of 65% or greater for each state and year in the study period. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and each participating state.

We ascertained smoking status in the following way: women who reported that they smoked any amount in the past 2 years were asked how many cigarettes they smoked per day on average during the 3 months before pregnancy and in the last 3 months of pregnancy. Categorical response options were none (0 cigarettes), less than 1, 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, 21–40, or 41 or more. In this study, prepregnancy smoking was defined as smoking any cigarettes in the 3 months before pregnancy. Prenatal smoking was defined as smoking any cigarettes in the last 3 months of pregnancy. Smoking cessation by the last 3 months of pregnancy was defined as smoking “none” in the last 3 months of pregnancy among prepregnancy smokers.

Depression and anxiety status was defined by an affirmative response to either or both of the following questions: “During the 3 months before you got pregnant, did you have anxiety?” and “During the 3 months before you got pregnant, did you have depression?”

Other covariates included in the analysis were maternal age; race and ethnicity; education; marital status; parity; state and neonatal birth year obtained from the linked birth certificate and health insurance coverage before pregnancy; health insurance coverage during prenatal care or at delivery; participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; alcohol binge drinking in 3 months before pregnancy and during the last 3 months of pregnancy; and physical abuse by a partner in the 12 months before pregnancy and during pregnancy were obtained from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System survey.

Data from the nine Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System states used in the study include 37,419 women. We excluded records with missing data on smoking (n=513), depression or anxiety(n=449), both smoking and depression or anxiety (n=29), and covariates (n=1,795), leaving 34,633 for analysis (92.6% of total sample). The characteristics of the sample were described by depression and anxiety status. Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of prepregnancy smoking, prenatal smoking, and smoking cessation were calculated by depression and anxiety status overall and by selected maternal characteristics, including health insurance coverage. Chi square tests at P<.05 were used to assess differences. Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios of smoking status by depression and anxiety status were calculated per methodology by Bieler et al17 controlling for all covariates. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 and SUDAAN 11 to account for the complex survey design of the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System.

RESULTS

For the total study sample (N=34,633), the majority of women were aged 25–34 years (56.2%), were non-Hispanic white (68.6%), had greater than 12 years of education (61.7%), were married (63.7%), were multiparous (58.1%), had private insurance before pregnancy (62.8%), and were not Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participants (56.0%). Overall, 16.9% (95% CI 16.3–17.4, n=5,769) of women reported depression, anxiety, or both during the 3 months before pregnancy (Table 1); 4.7% of women reported anxiety only, 4.3% depression only, and 7.9% reported both depression and anxiety. Compared with those without depression or anxiety, women with reported depression or anxiety were more likely to be younger (24 years or younger); non-Hispanic white; have 12 years or less of education; be unmarried; be enrolled in Medicaid insurance before pregnancy; participate in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children during pregnancy; be a binge drinker before pregnancy only; and experience physical abuse by a partner before or during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample by Reported Depression and Anxiety Before Pregnancy (N=34,633)*

| Characteristic | Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=5,769) | No Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=28,864) | P† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total‡ | 16.9 (16.3–17.4) | 83.1 (82.6–83.7) | |

| Maternal age (y) | <.001 | ||

| Younger than 20 | 9.6 (8.5–10.9) | 7.6 (7.2–8.1) | |

| 20–24 | 26.8 (25.1–28.5) | 22.1 (21.4–22.8) | |

| 25–34 | 53.2 (51.3–55.1) | 56.9 (56.1–57.7) | |

| 35 or older | 10.4 (9.4–11.4) | 13.4 (12.9–13.9) | |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | <.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 77.3 (75.7–78.8) | 66.8 (66.1–67.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 10.8 (9.7–12.0) | 14.8 (14.2–15.3) | |

| Hispanic | 6.7 (5.8–7.7) | 9.4 (8.9–9.9) | |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 6.0 (5.7–6.3) | |

| Other race | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 2.5 (2.2–2.8) | |

| Maternal education (y) | <.001 | ||

| Less than 12 | 19.3 (17.7–20.9) | 12.3 (11.8–12.9) | |

| 12 | 27.7 (26.0–29.4) | 24.3 (23.6–25.0) | |

| Greater than 12 | 53.0 (51.1–54.9) | 63.4 (62.6–64.2) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | ||

| Unmarried | 47.1 (45.2–49.1) | 34.0 (33.3–34.8) | |

| Married | 52.9 (50.9–54.8) | 66.0 (65.2–66.7) | |

| Parity | <.344 | ||

| 1 or more | 59.0 (57.1–60.9) | 58.0 (57.2–58.8) | |

| 0 | 41.0 (39.1–42.9) | 42.0 (41.2–42.8) | |

| Health insurance coverage before pregnancy | <.001 | ||

| Private | 52.0 (50.1–53.9) | 64.9 (64.1–65.7) | |

| Medicaid | 24.4 (22.8–26.1) | 13.6 (13.1–14.2) | |

| Other insurance | 2.8 (2.2–3.4) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | |

| Uninsured | 20.8 (19.3–22.5) | 19.2 (18.5–19.9) | |

| WIC during pregnancy | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 55.3 (53.4–57.2) | 41.7 (40.9–42.5) | |

| No | 44.7 (42.8–46.6) | 58.3 (57.5–59.1) | |

| Binge drinking before or during pregnancy | <.001 | ||

| None | 65.4 (63.5–67.2) | 75.5 (74.8–76.2) | |

| Before pregnancy only | 33.9 (32.1–35.8) | 23.7 (23.0–24.4) | |

| During pregnancy | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | |

| Physical abuse before or during pregnancy | <.001 | ||

| None | 90.2 (89.0–91.3) | 96.8 (96.5–97.1) | |

| During pregnancy only | 3.2 (2.6–4.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | |

| Before pregnancy only | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | |

| During and before pregnancy | 4.7 (3.9–5.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Data are % (95% confidence interval) unless otherwise specified.

Sample includes nine Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System states in 2009–2011: Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Differences based on χ2, P<.05.

Row percentages provided.

Overall, 26.5% (95% CI 25.9–27.2) of women with a recent live birth reported smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy. Women reporting depression or anxiety had significantly higher prepregnancy smoking prevalence compared with those not reporting either condition (46.7% compared with 22.5%, P<.01) (Fig. 1; Table 2). When examined by subgroups, women reporting depression or anxiety had higher prepregnancy smoking prevalence across almost all subgroups with the exception of Native Americans or Alaska Natives and women who were binge drinkers during pregnancy (Table 2). Depressed or anxious women with the highest pre-pregnancy smoking prevalence included those with less than 12 years of education (69.5%); younger than 20 years of age (66.4%); those who experienced physical abuse before and during pregnancy (66.0%), before pregnancy only (65.1%), and during pregnancy only (62.6%); unmarried women (65.2%); and binge drinkers before pregnancy only (61.5%). In adjusted analyses, women reporting depression or anxiety were 1.49 times more likely to smoke pre-pregnancy than those not reporting either condition (Table 3). Prepregnancy smoking prevalence was significantly higher for women reporting depression or anxiety compared with those not reporting either condition for all insurance categories with the highest smoking prevalence in those reporting depression or anxiety enrolled in Medicaid (67.7%) or who were uninsured (61.5%) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of smoking by reported depression or anxiety status (N=34,633). Sample includes 9 PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) states in 2009–2011: Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy: 46.7% (95% CI 44.8–48.6), 22.5% (95% CI 21.8–23.2); Smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy: 27.5% (95% CI 25.8–29.2), 10.5% (95% CI 10.0–11.0); and smoking cessation by last 3 months of pregnancy: 41.4% (95% CI 38.6–44.3), 53.8% (95% CI 52.0–55.6). *Difference in smoking status between women reporting depression or anxiety and those not reporting based on chi-square test, P < .05. †Smoking cessation calculated among women who reported smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy.

Tong. Maternal Smoking in Women With Depression or Anxiety. Obstet Gynecol 2016.

Table 2.

Smoking Prevalence Before and During Pregnancy by Reported Depression or Anxiety Status*

| Characteristic | Smoked in the 3 mo Before Pregnancy

|

Smoked in the Last 3 mo of Pregnancy

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=5,769) | No Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=28,864) | Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=5,769) | No Depression or Anxiety (Unweighted n=28,864) | |

| Total | 46.7 (44.8–48.6) | 22.5 (21.8–23.2) | 27.5 (25.8–29.2) | 10.5 (10.0–11.0) |

| Maternal age (y) | ||||

| Younger than 20†‡ | 66.4 (60.4–72.0) | 32.3 (29.4–35.3) | 40.2 (34.1–46.7) | 15.4 (13.3–17.9) |

| 20–24†‡ | 60.0 (56.2–63.6) | 33.7 (32.0–35.5) | 37.3 (33.7–41.0) | 16.6 (15.3–18.0) |

| 25–34†‡ | 40.6 (38.0–43.2) | 19.1 (18.3–20.1) | 22.6 (20.5–24.9) | 8.6 (8.0–9.3) |

| 35 or older†‡ | 25.5 (21.5–30.0) | 12.3 (11.0–13.8) | 15.0 (11.8–18.8) | 5.6 (4.7–6.7) |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white†‡ | 47.7 (45.5–49.9) | 24.9 (24.0–25.8) | 28.8 (26.8–30.9) | 12.0 (11.3–12.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black†‡ | 46.3 (40.7–52.0) | 20.3 (18.6–22.1) | 26.8 (22.4–31.8) | 9.8 (8.7–11.1) |

| Hispanic†‡ | 33.1 (26.4–40.6) | 12.3 (10.5–14.4) | 14.5 (10.4–20.1) | 3.7 (2.8–5.0) |

| Native American or Alaska Native‡ | 68.2 (50.6–81.8) | 51.9 (42.9–60.8) | 40.5 (25.8–57.1) | 20.0 (14.3–27.2) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander†‡ | 34.4 (24.6–45.6) | 13.3 (11.7–15.2) | 13.6 (7.7–22.9) | 4.2 (3.4–5.3) |

| Other race†‡ | 52.6 (40.6–64.3) | 23.9 (19.2–29.3) | 26.6 (17.6–38.1) | 12.7 (9.2–17.3) |

| Maternal education (y) | ||||

| Less than 12†‡ | 69.5 (65.0–73.6) | 35.8 (33.4–38.2) | 49.4 (44.7–54.0) | 22.9 (20.9–25.1) |

| 12†‡ | 56.4 (52.8–59.9) | 35.7 (34.0–37.3) | 35.0 (31.6–38.5) | 19.1 (17.8–20.5) |

| Greater than 12†‡ | 33.4 (31.0–35.8) | 14.8 (14.1–15.6) | 15.6 (13.8–17.5) | 4.8 (4.0–5.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried†‡ | 65.2 (62.4–68.0) | 38.9 (37.5–40.4) | 41.3 (38.5–44.2) | 21.3 (20.1–22.5) |

| Married†‡ | 30.2 (27.9–32.6) | 14.0 (13.3–14.7) | 15.1 (13.4–17.0) | 4.9 (4.5–5.4) |

| Parity | ||||

| 1 or more†‡ | 46.3 (43.8–48.7) | 21.2 (20.3–22.1) | 29.1 (26.9–31.4) | 11.4 (10.7–12.1) |

| 0†‡ | 47.3 (44.3–50.4) | 24.2 (23.1–25.4) | 25.1 (22.5–27.8) | 9.3 (8.6–10.1) |

| WIC during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes†‡ | 59.9 (57.3–62.4) | 33.2 (31.9–34.4) | 38.6 (36.0–41.2) | 18.0 (17.0–19.0) |

| No†‡ | 30.5 (28.0–33.2) | 14.8 (14.0–15.6) | 13.7 (11.9–15.8) | 5.1 (4.7–5.6) |

| Binge drinking before or during pregnancy | ||||

| None†‡ | 39.0 (36.7–41.3) | 15.9 (15.2–16.6) | 24.8 (22.8–26.9) | 8.2 (7.7–8.7) |

| Before pregnancy only†‡ | 61.5 (58.2–64.8) | 43.1 (41.4–44.9) | 32.5 (29.3–35.7) | 17.7 (16.3–19.1) |

| During pregnancy‡ | 47.5 (29.7–66.0) | 30.8 (23.0–39.8) | 36.5 (22.0–54.0) | 17.2 (11.6–24.6) |

| Physical abuse before or during pregnancy | ||||

| None†‡ | 44.5 (42.5–46.6) | 21.7 (21.0–22.4) | 25.7 (23.9–27.5) | 10.1 (9.6–10.6) |

| During pregnancy only†‡ | 62.6 (51.5–72.5) | 48.3 (40.6–56.1) | 39.4 (29.7–50.1) | 22.0 (16.3–29.0) |

| Before pregnancy only†‡ | 65.1 (49.8–77.8) | 34.8 (26.9–43.6) | 46.4 (31.7–61.8) | 18.4 (12.7–25.9) |

| During and before pregnancy†‡ | 66.0 (56.5–74.3) | 44.5 (37.0–52.2) | 46.5 (37.7–55.6) | 24.2 (18.6–30.9) |

WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Data are % (95% confidence interval).

Sample includes nine Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System states in 2009–2011: Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Difference in smoking prevalence in the 3 months before pregnancy between women reporting depression or anxiety and those not reporting based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Difference in smoking prevalence in the last 3 months of pregnancy between women reporting depression or anxiety and those not reporting based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Table 3.

Association Between Reported Smoking and Depression or Anxiety Status (N=34,633)*

| Crude Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Smoked in the 3 mo before pregnancy | ||

| Depression or anxiety | 2.08 (1.97–2.19) | 1.49 (1.41–1.57)† |

| None | Reference | Reference |

| Smoked in the last 3 mo of pregnancy | ||

| Depression or anxiety | 2.62 (2.42–2.84) | 1.69 (1.56–1.84)‡ |

| None | Reference | Reference |

| Smoking cessation by the last 3 mo of pregnancy§ | ||

| Depression or anxiety | 0.77 (0.71–0.83) | 0.86 (0.80–0.92)|| |

| None | Reference | Reference |

CI, confidence interval.

Nine Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System states in 2009–2011: Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Adjusted for maternal age, race and ethnicity, education, marital status, insurance coverage before pregnancy, parity, alcohol use or binge drinking before pregnancy, physical abuse before and during pregnancy, state and year of neonatal birth.

Adjusted for maternal race and ethnicity, education, marital status, insurance coverage during prenatal care and at delivery, parity, physical abuse before and during pregnancy, and state (n=33,492).

Smoking cessation by the last 3 months of pregnancy was calculated among prepregnancy smokers only.

Adjusted for maternal race and ethnicity, education, marital status, insurance coverage before pregnancy, parity, physical abuse before and during pregnancy, and state (n=9,350).

Table 4.

Reported Smoking Prevalence by Depression or Anxiety Status and Health Insurance Coverage*

| Health Insurance Coverage | Type of Health Insurance Coverage

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | Medicaid | Other† | Uninsured | |

| Before pregnancy | Unweighted n=20,189 |

Unweighted n=5,995 |

Unweighted n=860 |

Unweighted n=6,720 |

| Smoked in the 3 mo before pregnancy (N=34,633)‡§||¶ | ||||

| Depression or anxiety | 30.3 (27.9–32.9) | 67.7 (64.0–71.3) | 56.2 (45.5–66.3) | 61.5 (57.2–65.6) |

| None | 15.7 (14.9–16.5) | 35.4 (33.2–37.6) | 22.4 (18.3–27.1) | 35.6 (33.7–37.5) |

| During prenatal care or at delivery | Unweighted n=19,140 |

Unweighted n=12,523 |

Unweighted n=1,012 |

Unweighted n=1,063 |

| Smoked in the last 3 mo of pregnancy (n=33,733)‡§|| | ||||

| Depression or anxiety | 11.1 (9.5–13.0) | 44.8 (41.9–47.7) | 25.8 (17.6–36.2) | 15.3 (7.7–28.1) |

| None | 5.2 (4.8–5.8) | 21.1 (19.9–22.4) | 9.0 (6.6–12.1) | 5.4 (3.7–8.0) |

| Smoking cessation by the last 3 mo of pregnancy (n=9,342)§ | ||||

| Depression or anxiety | 61.5 (56.3–66.4) | 32.5 (29.2–36.0) | 48.4 (33.4–63.7) | 41.1 (20.3–65.6) |

| None | 66.0 (63.2–68.6) | 44.5 (42.0–47.0) | 60.5 (50.5–69.7) | 53.5 (40.0–66.5) |

Nine Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System states in 2009–2011: Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Other health insurance coverage includes Tricare, other military insurance, Indian Health Services, or state-specific State Children’s Health Insurance Programs or Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Difference between smoking status by depression or anxiety and those not reporting either condition for privately insured women, based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Difference between smoking status by depression or anxiety and those not reporting either condition for Medicaid-insured women, based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Difference between smoking status by depression or anxiety and those not reporting either condition for women with other insurance, based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Difference between smoking status by depression or anxiety and those not reporting either condition for uninsured women, based on χ2 test, P<.05.

Overall, 13.4% (95% CI 12.8–13.9) of women reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy. Women reporting depression or anxiety had significantly higher prenatal smoking prevalence compared with those not reporting either condition (27.5% compared with 10.5%, P<.01) (Fig. 1; Table 2). When examined by subgroups, women reporting depression or anxiety had higher prenatal smoking prevalence across all subgroups than those not reporting either condition (Table 2). Depressed or anxious women with the highest prenatal smoking prevalence included those with less than 12 years of education (49.4%); those who experienced physical abuse before and during pregnancy (46.5%) and before pregnancy only (46.4%); and unmarried women (41.5%). In adjusted analyses, women reporting depression or anxiety were 1.69 times more likely to smoke in the last 3 months of pregnancy than those not reporting either condition (Table 3).

Prenatal smoking prevalence was significantly higher for women reporting depression or anxiety for all insurance categories except for those who were uninsured. The highest prenatal smoking prevalence was among women reporting depression or anxiety enrolled in Medicaid (44.8%) or with other insurance (25.8%) (Table 4).

Among prepregnancy smokers, 50.2% (95% CI 48.6–51.7) of women reported smoking cessation by the last 3 months of pregnancy. Women reporting depression or anxiety had significantly lower proportions of smoking cessation compared with those not reporting either condition (41.4% compared with 53.8%, P<.01) (Fig. 1). After adjustment, prepregnancy smokers reporting depression or anxiety were significantly less likely to quit smoking by the last 3 months of pregnancy compared with their counterparts (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92) (Table 3). The point prevalence for smoking cessation was significantly lower for women reporting depression or anxiety enrolled in Medicaid compared with those not reported either condition (32.5% compared with 44.5%) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We found that women who reported depression, anxiety, or both had higher smoking prevalence in the 3 months before pregnancy compared with those not reporting either condition; almost half of women reporting depression or anxiety reported smoking. Women reporting depression or anxiety were more likely to smoke during pregnancy and less likely to quit by the last 3 months of pregnancy than those not reporting either condition. Subgroups with the highest smoking prevalence include younger women; those with less education; married women; enrolled in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; and those reporting binge drinking or physical abuse.

Individuals with mental health conditions may perceive tobacco use as an agent to relieve stress and anxiety, and some have reported that traditional cessation interventions do not address their mental health.18 However, evidence supports that continued smoking can worsen mental health conditions19 and tobacco cessation improves mental health conditions. In a meta-analysis of 26 longitudinal studies of smokers, tobacco cessation was associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and stress and improved mood and quality of life.20

Clinical trials of pregnant smokers have also documented improved mental health status and well-being after tobacco cessation.21–23 An incentive-based cessation trial resulted in increased cessation among pregnant women with diagnosed depression, and the intervention reduced the severity of postpartum depression symptoms.22 Furthermore, smokers with mental health conditions are just as motivated to quit as those not reporting mental health conditions.24,25 Patients and health care providers should be aware that tobacco cessation can contribute to improved mental health and improved pregnancy health.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines recommend screening for perinatal depression and anxiety at least once during the perinatal period8 in addition to routine screening for smoking.7,26 Given the high comorbidity between mental health status and smoking, preconception, interconception, and prenatal care present opportunities for health care providers to offer evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions and mental health care. Behavioral interventions are the first-line clinical approach for tobacco cessation during pregnancy.7 There is substantial evidence that behavioral cessation interventions significantly increase smoking cessation by the end of pregnancy and improve birth outcomes.27 Although cessation itself is associated with improved mental health,21–23 more research is needed to determine whether interventions that focus on both mental health conditions and smoking may improve both outcomes even further.21,28 Ideally, for smokers with mental health conditions, tobacco cessation treatment should be conducted in conjunction with treatment or referral for depression or anxiety.8 At minimum, all smokers before and during pregnancy should be offered standard-of-care tobacco cessation counseling, and women reporting depression or anxiety may need additional cessation support. Depressed or anxious women who reported physical abuse or binge drinking had very high smoking prevalence, suggesting also a need to screen and provide support for intimate partner violence and alcohol abuse.

We reported that smoking was more common among women reporting depression or anxiety regardless of health insurance coverage. Two thirds of Medicaid-enrolled women who reported depression or anxiety smoked before pregnancy and 45% smoked in the last 3 months of pregnancy. Currently, state Medicaid programs are required to provide comprehensive tobacco cessation treatment to pregnant smokers, and almost all meet this mandate.29 Increased awareness and broad promotion of tobacco cessation benefits can increase cessation treatment utilization.30,31 Additionally, all state programs provide at least some mental health services to Medicaid beneficiaries,15 and many states offer coverage of depression screening and treatment for pregnant women.32 Most individual and small group health insurance plans and Medicaid Alternative Benefit Plans are required to cover mental health and substance use disorder services.15

This analysis has limitations. First, smoking status was self-reported. Although the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System ascertains more smokers than other population-based sources relying on self-report,33 our results may underestimate the true prevalence.34 Second, depression and anxiety were also self-reported, and the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System does not collect data on clinical diagnosis or treatment for these conditions. However, the self-reported estimates of depression (12.2%) and anxiety (12.5%) in the 3 months before pregnancy are consistent with estimates based on self-reported symptoms meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition diagnostic criteria of depression (8–11%) and anxiety (12–15%) in pregnant and nonpregnant women.35,36 Third, the study is cross-sectional so a causal association cannot be assessed for smoking or depression and anxiety. Finally, results may not be generalizable to women outside of the study states, to those with pregnancy loss, nor outside of the study period.

In conclusion, health care providers have an opportunity to identify and treat reproductive-aged women with tobacco cessation interventions and mental health care. Health care providers should inform patients that tobacco cessation may improve pregnancy outcomes and maternal mental health status. All smokers should be offered cessation counseling, and women reporting depression or anxiety may need additional cessation support.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Working Group for coordinating data collection. A list of members is available at: http://www.cdc.gov/prams/pdf/researchers/prams-working-group_508tagged.pdf.

Footnotes

Presented at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 5th Biennial Mental Health Surveillance Meeting, September 10, 2015, Atlanta, Georgia.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke before, during, and after pregnancy. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Reproductive Health; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/tobaccousepregnancy/index.htm. Retrieved July 18, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.USDHHS. Healthy people. 2020 Available at: www.healthy-people.gov/2020. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- 4.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 2):S125–40. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin RD, Keyes K, Simuro N. Mental disorders and nicotine dependence among pregnant women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:875–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255979.62280.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy–pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smoking cessation during pregnancy Committee Opinion No. 471. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1241–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182004fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Screening for perinatal depression. Committee Opinion No. 630. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1268–71. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000465192.34779.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen AM, Prince CB, Dietz PM. Postpartum depressive symptoms and smoking relapse. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmichael SL, Ahluwalia IB. Correlates of postpartum smoking relapse. Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:193–6. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salimi S, Terplan M, Cheng D, Chisolm MS. The Relationship between postpartum depression and perinatal cigarette smoking: an analysis of PRAMS data. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: depression in adults: screen. 2016 Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/recommendations. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- 13.Siu AL U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:622–34. doi: 10.7326/M15-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Tobacco cessation. Available at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Tobacco.html. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- 15.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health insurance and mental health services. Available at: http://www.mentalhealth.gov/get-help/health-insurance. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- 16.Shulman HB, Gilbert BC, Msphbrenda CG, Lansky A. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:74–83. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:618–23. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C, Bryant J. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006414. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:297–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701. 1p following 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cinciripini PM, Blalock JA, Minnix JA, Robinson JD, Brown VL, Lam C, et al. Effects of an intensive depression-focused intervention for smoking cessation in pregnancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:44–54. doi: 10.1037/a0018168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez AA, Skelly JM, Higgins ST. Financial incentives for smoking cessation among depression-prone pregnant and newly postpartum women: effects on smoking abstinence and depression ratings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:455–62. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon LJ, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Mongeon JA, Bernstein IM. Psychological symptoms following smoking cessation in pregnant smokers. J Behav Med. 2006;29:151–60. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JJ, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Tsoh JY, Humfleet GL, et al. Depressed smokers and stage of change: implications for treatment interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siru R, Hulse GK, Tait RJ. Assessing motivation to quit smoking in people with mental illness: a review. Addiction. 2009;104:719–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobacco use and women’s health. Committee Opinion No. 503. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:746–50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310ca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub4. Art. No.: CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph JG, El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG, Johnson AA, et al. Reducing psychosocial and behavioral pregnancy risk factors: results of a randomized clinical trial among high-risk pregnant African American women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1053–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, Ganiats TG. Medicaid coverage of tobacco-dependence treatment for pregnant women: impact of the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:e27–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong VT, England LJ, Malarcher A, Mahoney J, Anderson B, Schulkin J. Clinicians’ awareness of the Affordable Care Act mandate to provide comprehensive tobacco cessation treatment for pregnant women covered by Medicaid. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:686–688. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Land T, Warner D, Paskowsky M, Cammaerts A, Wetherell L, Kaufmann R, et al. Medicaid coverage for tobacco dependence treatments in Massachusetts and associated decreases in smoking prevalence. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NIHCM. Identifying and treating maternal depression: strategies and considerations for health plans. NIHCM Foundation Issue Brief. 2010 Available at: http://www.nihcm.org/pdf/FINAL_MaternalDepression6-7.pdf. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- 33.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D’Angelo DV, England LJ. Estimates of smoking before and during pregnancy, and smoking cessation during pregnancy: comparing two population-based data sources. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:179–88. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ, Burley K, Tong VT, Dube SR, et al. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:355–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among U.S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:830–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vesga-López O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:805–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]